Abstract

Background:

There remains critical need for community-based approaches affirming youth voices and perspectives in HIV prevention.

Objectives:

We established an adolescent health working group (AHWG) to convene youth, parents, providers, and advocates in agenda-setting for interventions to increase Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake in Durham.

Methods:

Our two study phases included six AHWG meetings from 2019-2020, and youth-only meetings guided by a theoretical framework of participatory engagement known as Youth Generating and Organizing (GO). We also developed materials such as an AHWG mission statement and themes of outstanding HIV informational needs, recruited for youth-only meetings where data generation occurred, and solicited opinions about HIV risk and sustaining HIV prevention long-term.

Lessons Learned/Conclusions:

Engaging adults in youth-focused HIV prevention differs from engaging youth themselves. Creating a group in which to discuss adolescent sexual health involves a long-term vision of building trust, comfort and breaking down sensitivities and stigma to reduce HIV inequities.

Keywords: Adolescent health, HIV/AIDS, Health equity, Community-based participatory research, Blacks

BACKGROUND

Youth ages 13 to 24 accounted for 20% of new HIV infections in the United States (US) in 2020.1 Black youth accounted for 56% of the HIV/AIDS diagnoses that occurred in this age group.1 Programs and policies for HIV prevention among youth are often created without their input.2–5 Youth-focused participatory research has begun to shift this narrative, increasing community mobilization and reaching youth whose voices are often not heard.2–4 Excluding youth voices results in identifying the wrong solutions to the wrong problems, because youth themselves are the best experts to guide these efforts. The consequences of not doing so include wasted grant funding and limited or no progress in achieving goals such as reducing HIV inequities among youth. Ways to engage youth include their involvement in research design, community advisory boards, as navigators in clinical settings for HIV prevention, and youth-led advocacy programs.4,6–9 The Project Supporting Operational AIDS Research involved youth in a two-day meeting to discuss HIV implementation science questions and found that youth involvement led to bidirectional capacity strengthening and addressing key ethical considerations with minors.6–8

We aimed to increase HIV prevention for youth through understanding youth’s awareness of and attitudes towards Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).10–13 PrEP medication, like tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine, is a daily pill reducing risk of HIV acquisition by over 90%. PrEP is approved for youth ages 12 and up weighing at least 35 kg.12,14,15 Approximately 80% of youth, however, who could benefit from PrEP do not receive prescriptions for it.10–13 Reasons for this include a lack of comprehensive sex education in public schools, stigma around HIV, and limited healthcare access.9,10,11 To overcome these barriers and identify others to increase access to, uptake of, and adherence to PrEP, it is critical that youth voices are centered in this work.1,4,9 This study was done against the backdrop of high HIV incidence among Black youth in North Carolina (NC).16–19 Out of the 100 NC counties, Durham County—is nearly 40% Black and has the fourth highest rate of reported HIV infection NC, with 25.7 cases per 100,000 (versus the state rate of 19.3).10,19 Identifying ways to improve HIV prevention efforts among Black youth, particularly in the US South are urgent.10,20–22

We built upon formative research from Project IFE (I’m Fully Empowered), a community-engaged study with Black women living in public housing in Durham which was conducted by some of our research team members, to pinpoint community resources and priorities for HIV prevention .23 Project IFE participants, through workshops and qualitative interviews expressed a clear desire to address sexual and reproductive health risks among youth in the community. Responding to this request, we sought to engage youth and adults in the Durham community in research with a focus on HIV prevention among Black youth in the present research. While the research team recognized that youth needed to be involved in the development and implementation of a research strategy focused on them, the majority of the project was initially designed without youth as members of the research team.24 The goal of this paper is to report on the process by which we engaged youth, lessons learned in youth-focused work on HIV prevention, and to guide similar efforts in different locations and demographic groups.

METHODS

Study design and phases

Our study design was exploratory and observational, with mixed-methods data collection that occurred across three project phases to: 1) establish an Adolescent Health Working Group (AHWG) of adults and youth stakeholders to jointly develop a research agenda; 2) use participatory Youth Gather and Organize (Youth GO) workshops to qualitatively learn about youth’s perspectives and identify priorities for research/intervention on multi-level factors influencing PrEP access and uptake;26 and 3) conduct surveys (N=100) and interviews with Black youth in Durham on PrEP awareness and attitudes (N=15). We report phases one and two in this paper, and all activities were fully approved the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

We began by re-contacting our Project IFE partners, which were local universities, the Durham Housing Authority (DHA), and community-based organizations which are assets that provide local HIV services in the defined community of Durham that is predominantly comprised on African American residents.23 Team members introduced the project at a Project IFE meeting at a DHA location, and then began referral recruitment through DHA and community-based organizations. The AHWG had representatives from the DHA (who provided housing and recreational services and perspectives on serving youth), LGBTQ advocacy groups (who work on raising awareness on HIV inequities for Black Queer youth), youth healthcare providers (who are sensitive to the needs of increasing youth engagement in research), the Department of Public Health (who were motivated to identify ways to offer more youth-focused HIV prevention events), community-based organizations (such as HIV prevention service providers that serve majority African American Durham residents), faith leaders (one of whom is a youth-trusted pastor and artist), parents (of varying ages), and youth themselves. These groups were identified based on their importance in the African American community in Durham, given the diversity in the types of services provided and shared mission of addressing social inequalities. Partners were asked about their willingness to participate and share their priorities for making the AHWG a mutually beneficial partnership; as an exemplar, at the AHWG’s first meeting, team members asked who else should be in the room and then focused recruitment on reaching additional youth and faith leaders.

To prioritize youth voices after the second meeting, adult representation was capped at 13, and all adults were asked if they would cede their membership to a youth, which six chose to do. When youth were asked to join the AHWG, they were told that the purpose of the group was to learn about their needs related to HIV prevention and how to identify more resources in the community. They were also told that they would be paid for attending monthly meetings which never exceeded two hours in length, were at central locations they were familiar with, and where food was provided. Between meetings, AHWG members received reminder texts and emails from study team members about meetings, and to answer any questions related to the study. One of these team members was a youth herself with several years of community experience in Durham with Black residents, and the other was a well-experienced community engagement coordinator who was a member of the original Project IFE team and very familiar with all partners and was able to assist youth with getting transportation to and from AHWG meetings when needed.

Overarching conceptual framework for youth engagement

The situated-Information, Motivation, and Behavioral skills (sIMB) model has been used to explain engagement in HIV risk reduction and PrEP uptake, where each of the named constructs interact dynamically to promote behavior change.25 sIMB model posits that PrEP initiation and adherence is contingent on information access, motivation to act and skills to act, and community context conducive to maintaining behaviors.25 However, this model has not been applied to examine PrEP awareness among Black youth using a participatory approach; therefore, we used the sIMB model to identify priorities for research and intervention on multi-level factors (e.g., individual, intrapersonal, structural) that influence HIV risk, PrEP access and uptake, and barriers to care among Black adolescents in Durham, North Carolina.

Project Phase I: AHWG meetings

The AHWG met six times from Fall 2019 to Summer 2020, in-person at a DHA community center until March 2020 when they moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. About 15-30 total (15 to 25 community members and between five to seven academic members) attended each meeting. Meetings were slightly smaller once COVID-19 hit. While the number of youth increased slightly over time, the majority of community members were adults. All AHWG members self-identified as African American or Black, and youth ranged in age from 17 years to 26 years of age. Adults ranged in age from late twenties to mid-sixties. Throughout all meetings, team members took notes during AHWG discussions and shared notes back with AHWG members for their feedback at the next meeting. Table 1 reports AHWG meeting sizes and key discussion topics which were responses to two standing prompts that were asked at every meeting: 1) “What do we need to address to increase HIV awareness in the community?”; and 2) what information do youth need to be empowered to prevent HIV?.; this content informed what was included in AHWG newsletters and the themes depicted in Table 1. After the sixth meeting in Summer 2020, all community members were sent a summary of the exit discussion conducted at the final meeting. The exit discussion prompt at the final meeting was “What would you like to see this study do as it completes its activities?” In response, AHWG members requested and received a certificate of completion, and initiation of quarterly newsletters at their request to hear about partners and research collaborations beyond current grant funding.

Table 1.

AHWG meeting information (held over 11 months between 2019 and 2020)*

| Date of AHWG Session | Number of Attendees | Topics raised by AHWG members related to Adolescent Health and HIV in Durham Community |

|---|---|---|

| August 2019 | 25 (20 adults, 5 youth) | • Religion, churches, faith community as partners in this work • Access to care is an issue, (insured youth unwilling to talk to parents)* • Finding Same Gender Loving Black men as community advocates • “Seasons” of HIV risk for youth at different ages must be considered • Understanding larger issues than health or HIV in the community* • Structural barriers to HIV prevention medication (PrEP) and staying in care • Youth and transportation are barriers to AHWG and also getting HIV care* • Youth must be taught more sex education in schools • Making sure we do not silence youth in this work* |

| September 2019 | 18 (12 adults, 6 youth) | • PrEP needs to be available for the whole community • HIV challenges are different for youth and grown-ups* • Reaching youth must be done at the right place with the right info* • Involving parents, trusted adults and the community to reach youth over time is necessary for sustainability • PrEP info is for everyone should not be only for specific groups • Youth leadership has to be the focus of our activities* |

| October 2019 | 21 (13 adults, 8 youth) | • How to address concerns about the PrEP lawsuit that had received media coverage • Lack of school-based education on sex and contraception* • Finding youth spokespeople who are willing to share their journey, perhaps those living with HIV* • Getting PrEP, affording PrEP, and privacy in taking PrEP are real challenges • Finding PrEP materials that don’t discuss ‘high risk’ is imperative* • Using art to share our mission and educate youth about HIV can reach a young generation* |

| November 2019 | 19 (12 adults, 7 youth) | • Finding youth spokespeople who are willing to share their journey* • Allowing youth to decide the title for Youth GO (boring) • Finding PrEP materials that don’t discuss ‘high risk’ • Addressing perceptions about study eligibility for Aim 3 surveys • which did not specify ‘Black youth’ or ‘LGBT youth’* • Figuring out how to create a ‘youth-only advisory board’ which is not the AHWG but can advise its members (possible via Youth GO?)* |

| February 2020 | 16 | • Sex education and PrEP counseling need to addressing power and consent around condoms and sex • Future programs must address that youth staying on PrEP every day will be hard* • Programs like this should not disappear as soon as the ‘funding ends’ • HIV and PrEP programs need to be cognizant of the many other things our community is dealing with such as racial injustice and police brutality and violence |

| June 2020 (virtual) | 20 (12 adults, 8 youth) | • Getting PrEP, affording PrEP, and privacy in taking PrEP are real challenges • Finding PrEP materials that don’t discuss ‘high risk’ is imperative* • Using art to share our mission and educate youth about HIV can reach a young generation* • HIV and PrEP programs need to be cognizant of the many other things our community is dealing with such as racial injustice and police brutality and violence • AHWG participants want to see newsletters with periodic updates from the program including study results • Periodic AHWG meeting just to ‘catch up’ virtually would be welcome* |

denotes topics that were concerns voiced by youth

When we began analyses for this manuscript, we first created a free list of AHWG meeting discussion topics in response to the prompts described above. We then used the pile sorting method with AHWG members to name, reach consensus on, and organize themes in subsequent meetings.33 All AHWG members were invited to contribute to manuscript writing; one adult and three youth members contributed by participating in virtual meetings to refine the description of the themes, lead sections of manuscript writing, and review manuscript revisions. We discussed with youth the time commitment for the manuscript, assuring them no more than ten hours total would be requested and that authorship order was their choice and corresponding to how involved they wanted to be. Notably the adult AHWG member and two of the three youth had existing experience in qualitative methods and analyses. The only youth member who did not was given orientation at each planning meeting and asked to review the outline and then provide oral feedback on what notes were salient to him and that needed to be reflected in study results. All AHWG who were authors also sent a full description of all manuscript changes requested during the journal review process, invited to make all comments and assured their changes (if any) would be incorporated before resubmission was completed.

Regarding increasing youth leadership, many conversations focused around the AHWG being an adult-dominated space and the need for community and academic AHWG members to have the cultural humility for youth to have the space to tell their story. Younger academic team members began co-leading meetings, led Youth Generate and Organize (GO) meetings, and sought funding for additional Youth GO workshops, youth-led participatory research training, and youth-focused dissemination. We were asked to increase information about sexual health more broadly than HIV and PrEP, as most adolescents lack comprehensive sex education and need projects such as this to link to school-based sex education to provide continuity. AHWG members also discussed the need for materials on HIV and PrEP to extend beyond ‘high-risk’ subpopulations and be relevant for the entire community. Discussions also centered around a lack of understanding and confusion regarding sexual health laws and policies, specifically around what services adolescents could access on their own without a parent or guardian. Underlying these conversations was a desire to speak about community resiliency and resources rather than what the community lacks.

Project Phase II: Protected youth-only spaces through Youth GO

Youth-only meetings were facilitated using an existing participatory model known as Youth GO which consists of five processes: (a) climate settings such as with guiding principles; (b) generating or setting an agenda for discussion; (c) organizing the nature of the discussion such as in small groups; (d) selecting the key topics and takeaways from discussion; and (e) debrief and discussion of takeaways.26 As of November 2020, three Youth GO sessions were held, with group sizes ranging from four to seven youth. Youth were grouped by age (13 to 17 years were together, and ages 18 to 24 were together). Sessions were two to three hours in length, each youth only participated once and was paid, and discussions were held on days and times that were convenient for each set of attendees. At each session, a priori topics were presented to youth for them to then adapt and generate their own prompts from. Session one focused on sources of health information broadly, and Sessions 2 and 3 asked what youth had heard about HIV; and barriers and facilitators of sexual health preventive behaviors (including but not limited only to HIV prevention). All three sessions were recorded and transcribed which were reviewed and structurally coded. Team members also utilized the pile sorting methods on notes taken and images captured during brainstorming sessions to help contextualize the themes and takeaways that resulted from the process.33 After completion of each workshop, participants were given short feedback forms asking their satisfaction with participation, comfort level with being honest, and willingness to participate in future sessions.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS

Project Phase I: AHWG Meetings and Lessons Engaging Partners

A key issue that arose early on in our AHWG meetings was the distinction between having group members who represented youth organizations versus youth themselves. We responded to by:

creating a suggestion box where any AHWG members could anonymously share suggestions and give feedback

inviting younger research team members to assist with all group meeting facilitation, and providing each of them with several planning calls to rehearse the agenda items and meeting activities they would lead or assist with, even though all had some previous research experiences.

leading youth-only meetings to discuss HIV prevention in a space that was facilitated by our younger research team members (Phase II of the study, which was planned before the AHWG was formed but shared with the working group for their input).

A related challenge of creating a safe space for youth to speak in an adult-dominated meeting came in the form of unnecessary use of technical jargon. Future research with this community and other youth who may be under-engaged in research should minimize unnecessary jargon, anticipate the need for informational materials, and invite youth to be research team members from the AHWG (which has now been done with our working group members on a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded HIV/STI reduction project).

The suggestions box proved to be an effective means which the research team could address the needs of the AHWG that the:

research team needed to answer questions before, during, and after the meetings

community-level HIV and PrEP awareness needed to be increased

stigma around HIV prevention topics may have been exacerbated by being in an academic-led space

research team could have had more explicit discussion about the racial divide between the majority white researchers and a majority Black community by acknowledging recent racial injustices that had occurred locally and nationally (e.g.,, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd murders).

Ongoing discussion with AHWG members about these topics led to more discussion of community wants and needs, including identifying free and no cost counseling services for DHA residents who have requested this due to a local shooting that happened in their residential community and in response to the aforementioned racial injustices; in line with good community participatory practice this addressed the local relevance of public health issues and addressing multilevel determinants of health.29 Once COVID-19 control measures required virtual meetings, many AHWG members still attended meetings, both for engagement in the study and to combat broader social isolation. Several group members expressed feeling happy that the team was paying attention to the needs of the community, who explicitly stated they wanted to see ongoing presence from the research team to encourage mutual benefit in the partnership as described when partners originally agreed to participate. Additional virtual meetings are being planned for 2021. Summarized below is phase III, because the AHWG provided input in real time.

Project Phase II: Lessons Learned in Youth GO informed by sIMB

As mentioned, our team had designed youth-only sessions in Phase II (Table 2), and the need for these sessions was consistently reinforced by our AHWG. We sought input from the AHWG as these sessions took place and shared findings with them at three of our six AHWG meetings. As noted by our AHWG, there was a need for this space when considering the unique cultural identity of Black youth. AHWG meetings were held with a predominantly Black community and were predominantly adult-dominated even if some of these individuals represented youth-focused organizations. In the Black community, deference to elders is a widely taught cultural value. It was not surprising, therefore, that the adults in the space were more vocal about the needs they saw related to HIV prevention in the community, rather than the youth themselves.

Table 2.

Youth GO Session Takeaways Corresponding to sIMB constructs (3 sessions, youth ranged in age from 13 to 24)

| Thematic areas from sIMB model | Younger youth (ages 13-17; N=10 total) | Older youth (ages 18 to 24; N=7 total) |

|---|---|---|

| Information (e.g., what youth heard about HIV, side effects of medication) | Examples of what youth had heard or said about HIV: • Easy to die from HIV • Easy to overdosing on daily pill to prevent HIV • HIV is nasty and not curable • You know you have HIV when it hurts to urinate |

Examples of what youth had heard or said about HIV: • You can get it thru sex • HIV is a sexually transmitted disease, also it is non-curable • You die from HIV |

| Example of what youth said about taking PrEP and side effects: • Taking PrEP makes you feel better • Swallowing pills is hard • Remembering time is hard |

Example of what youth said about taking PrEP and side effects: • Not knowing if it’s going to work and side effects • The taste • Got harder because I got tired of smelling pills |

|

| Motivation (e.g., preventing HIV, taking PrEP) | Examples of youth comments related to perceived HIV susceptibility and motivation to act • No HIV-specific worries related to sex or education • You can take vitamins for like stuff in your body. If you have something bad going in your body you can go to the doctors and they prescribe medicine to help you [when you are motivated to not get HIV] |

Examples of youth comments related to perceived HIV susceptibility and motivation to act • I believe the facts you have. HIV will be enough just to make you want to keep taking it • Wanting to get better • Be careful who you have sex with • Check condoms for holes |

| Examples facilitators to take PrEP pills once deciding to take action: • If you ever forgot to take your meds write it down • Easier if it’s in gummy form or you can crush it up with water |

Examples facilitators to take PrEP pills or prevent HIV once deciding to take action: • You can keep getting it from the pharmacy; you have to keep taking it to help health-wise • Celebrity influence [helps] • Go with friends when they get tested |

|

| Behavioral skills (e.g., facilitators of PrEP, sources of information) | Examples of sources of information youth access when motivated to learn about HIV: • I hear about it from the website and ask my mom • I get it from a website and school and I hear it from friends • Can talk to doctor, mom, dad, or school nurse but nurse at school can’t give you medicine |

Examples of sources of information youth access when motivated to learn about HIV: • Can learn about it from the doctor and clinics such as planned parenthood • Comfortable talking to parents, but do not generally do so • Discussing sex can be easier with older cousin who is close in age and relates • Doctors can be trusted to talk about HIV since their job is to take care of you |

| Examples of contextual factors which facilitate HIV prevention behaviors • To help get refill just call doctors • Mom helps remember not doctor |

Examples of contextual factors which facilitate HIV prevention behaviors • Medications/vitamins are expensive; proven effectiveness of a medication; if the sources are allowable then I’ll be more inclined to take the medicine • Access to health information itself is a form of support • HIV prevention is not the only issue; overall mental, physical and emotional protection is important |

Adults were often speaking from the vantage points of parents but doing so by making assumptions about the questions their children or other youth might have. Summarized in Figure 1 are themes that results from Youth GO which are further conceptualized using the sIMB model to summarize findings across all three sessions. Our prior analyses of these groups focused only on PrEP-specific skill building which were areas of focus in the second and third Youth GO sessions. Therefore, findings presented here are from all three completed sessions, discuss HIV prevention more broadly, and are delineated by younger versus older age. This age delineation is because the sessions were similarly separated (two each were conducted with younger ages 13 to 17, and one was conducted with ages 18 to 24 because the forth was cancelled due to COVID-19 and the need for this type of engagement to be done in person). As shown, information about HIV cited by youth was similar between younger and older ages, and many concerns around PrEP related to pill size and side effects. Some differences in motivations were seen between ages, such that older youth seemed to perceived greater susceptibility to HIV and need to engage in preventive behaviors other than taking PrEP such as checking condoms for holes and being selective with sexual partners. Behavioral skills such as seeking support were similar by age, in that doctors and online sources were mentioned as trusted, though older youth felt less willing to talk to parents. It is noteworthy that older adults comprised the majority of Youth GO participants and were more responsive likely because they were more sexually active.

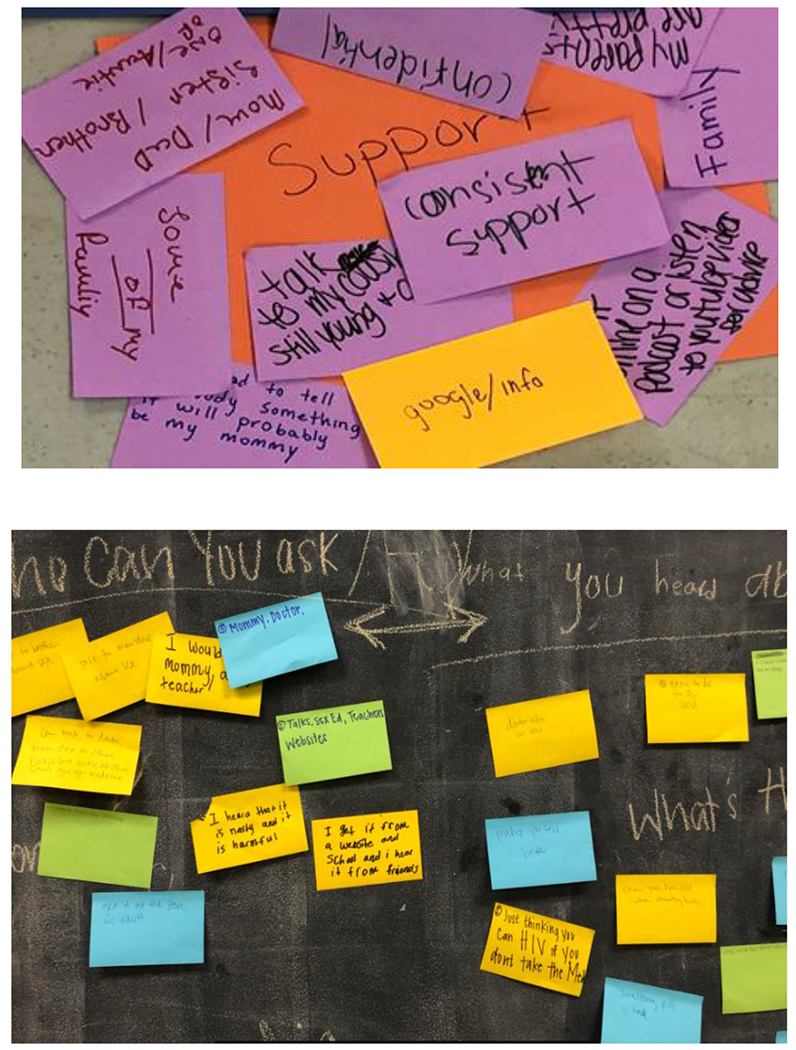

Figure 1a-c.

Youth GO session summaries responding to prompts about where youth access health informational support

Shown above are responses given by youth in a Youth GO session when asked where they go to access support related to health information or other needs.

Project Phase III: Community Surveys Exploring HIV and PrEP awareness

As of January 2021, online surveys were completed with youth ages 13 to 24 who were Black and Durham County residents. We presented the study flyer for feedback at three of our AHWG meetings and received recommendations for online survey recruitment from three AHWG member organizations. A quantitative self-administered online survey assessed awareness of and attitudes toward PrEP from a larger sample of youth (13-24) in Durham to contextualize findings from Youth GO workshops. The quantitative survey included adolescents aged 13-24 who lived in the Durham community and identified as Black or African American. All participants completed the brief quantitative survey lasting about 20 minutes that included questions about demographics, PrEP awareness and attitudes, PrEP use, healthcare access, stigma, and sexual behaviors. From the larger sample of survey respondents, a subsample were invited to complete qualitative one-hour in-depth interviews. Interviews were semi-structured in nature, and explored HIV prevention awareness, PrEP awareness, sources of trust health communication and barriers to seeking HIV prevention care. The interview guides were created at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple questions and prompts were added to contextualize the impact of COVID-19 on Black youth in the community broadly and how COVID-19 intersected with HIV prevention efforts and behaviors that would put youth at risk for acquiring HIV. Despite the limitations of the COVID-19 pandemic, recommendations and assistance from AHWG members allowed us to complete 87% enrollment for surveys (87 out of 100 surveys) and 87% enrollment for interviews (13 out of 15 interviews). Qualitative and quantitative data analyses are currently being conducted, with invitations from youth AHWG to assist in all analyses, manuscripts, and dissemination of findings.

Overall takeaways: Need for community-level HIV prevention awareness

Our study identified an overall need for HIV prevention information not only for youth, but for the adults in the community as well; this is reflected in Table 1 themes related to information need, many of which were from adults themselves about their need for further education. Additionally, in our AHWG meetings and Youth GO sessions, both adults and youth expressed uncertainty about PrEP, as well as other forms of HIV prevention modalities. Summarized below are key steps we took in addressing informational needs which were made available at all study events for both study phases:

- Need: youth were aware of HIV prevalence or PrEP availability

- Steps: Share existing HIV materials created by reputable organizations such as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Need: youth and adults had questions regarding minor consent laws in North Carolina related to HIV preventive care

- Steps: Creating and dissemination one-page fact sheets with plain language information about minor consent laws related to accessing preventive care such as HIV testing and pregnancy testing for youth under the age of 18

- Need: adults had questions about recently publicized lawsuits pertaining to PrEP and the safety of PrEP for their children

- Steps: several breakout discussion sessions related to PrEP lawsuit information, ways to respond to questions from loved ones, and sharing plain language summaries of the safety of PrEP and public information related to the lawsuit pertaining to the PrEP patent rather than PrEP safety

In line with the overarching goal of this project, our phase I and II study activities highlighted the importance of youth-generated feedback on HIV prevention activities targeted to them. Our team learned that adults had many reservations that differed from those of youth. For example, adults were concerned about PrEP safety and side effects, while youth were concerned with the idea of taking daily pills and did not perceive themselves at risk of HIV infection (See Table 1 for notation of youth-identified themes). The concept of ‘risk,’ which was an included term on many HIV prevention materials, was neither meaningful nor perceived as positive by adults or youth, and future materials should replace this terminology and simplify information about whether PrEP will ‘benefit’ individuals instead. In conclusion, youth engagement throughout the research process is the only way in which to generate evidence for policies and programs to reduce the impact of HIV disparities in the Black community.27–31 Doing so means that youth must be involved in the entire process, from grant writing to scholarly writing and dissemination of study findings.1,2,27,32,34 One way in which to encourage this type of engagement is to employ youth as research team members, and compensate them for conducting research activities which can also create professional development opportunities for them. Next, youth-only spaces and youth-led activities must be at the center of study activities. As our second phase using the participatory Youth GO approach made clear, finding ways to engage youth in authentic ways that enable them to fully participate and direct the process to promote long-term increases in awareness of HIV prevention resources for African American youth in Durham. Third, having a racially diverse research team that understands the cultural nuances of working in communities of color is an important way to improve community trust.35,36 Lastly, transparency in the goals of the research and ongoing engagement between research and community can improve both research outcomes and work in reducing the inequities experienced in Black youth communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Duke-UNC Joint Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Program (5P30 AI064518 and P30-AI050410-22). We thank the both the UNC and Duke CFARs for their support, including faculty mentors Dr. Carol Golin, Dr. Alexandra Lightfoot, Dr. Audrey Pettifor at UNC, Dr. Amy Corneli at Duke, and Ms. Cathy Emrick and Dr. Kate MacQueen, UNC CFAR Developmental Core leadership.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHHSTP AtlasPlus. Updated 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/index.htm. Accessed on March 1, 2021.; Powers JL, Tiffany JS. Engaging youth in participatory research and evaluation. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2006. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Zeldin S, Christens BD, Powers JL. The Psychology and Practice of Youth-Adult Partnership: Bridging Generations for Youth Development and Community Change. Am J Community Psychol. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9558-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakil S, McKinney de Royston M, Suad Nasir N, Kirshner B. Rethinking Race and Power in Design-Based Research: Reflections from the Field. Cogn Instr. 2016. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2016.1169817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods-Jaeger BA, Sparks A, Turner K, Griffith T, Jackson M, Lightfoot AF. Exploring the social and community context of African American adolescents’ HIV vulnerability. Qualitative health research. 2013. Nov;23(11):1541–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekker LG, Johnson L, Wallace M, et al. HIV and adolescents: Focus on young key populations: Focus. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.2.20076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lally MA, van den Berg JJ, Westfall AO, et al. HIV Continuum of Care for Youth in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denison JA, Pettifor A, Mofenson LM, et al. Youth engagement in developing an implementation science research agenda on adolescent HIV testing and care linkages in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2017. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denison JA, Tsui S, Bratt J, Torpey K, Weaver MA, Kabaso M. Do peer educators make a difference? An evaluation of a youth-led HIV prevention model in Zambian Schools. Health Educ Res. 2012. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinead DM, Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Bekker LG. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: Observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.7.21107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmon JL, Collins-Ogle M, Bartlett J a., et al. Retention Strategies and Factors Associated with Missed Visits Among Low Income Women at Increased Risk of HIV Acquisition in the US (HPTN 064). AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanny D, Jeffries WL, Chapin-Bardales J, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men — 23 Urban Areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6837a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanner MR, Miele P, Carter W, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for prevention of HIV acquisition among adolescents: Clinical considerations, 2020. MMWR Recomm Reports. 2020. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.RR6903A1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horvath KJ, Todd K, Arayasirikul S, Cotta NW, Stephenson R. Underutilization of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Services Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth: Findings from Project Moxie and TechStep. Transgender Heal. 2019. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2019.0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veronese F, Anton P, Fletcher CV, et al. Implications of HIV PrEP trials results. In: AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses; 2011. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes D. FDA treads carefully with PrEP. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(12)70160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holloway IW, Dougherty R, Gildner J, et al. Brief Report: PrEP Uptake, Adherence, and Discontinuation among California YMSM Using Geosocial Networking Applications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC HIV Prevention Progress Report.; 2019. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Biello-SGMAwardPresentation-toshare.pdf.

- 18.North Carolina HIV/STD/Hepatitis Surveillance Unit. 2018 North Carolina HIV surveillance report. 2019;2019(December):1–72. https://epi.dph.ncdhhs.gov/cd/stds/figures/hiv18rpt_02042020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rice WS, Stringer KL, Sohail M, et al. Accessing Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Perceptions of Current and Potential PrEP Users in Birmingham, Alabama. AIDS Behav. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02591-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. Brief Report: The Right People, Right Places, and Right Practices: Disparities in PrEP Access among Black Men, Women, and MSM in the Deep South. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill S, Clark J, Simpson T, Elopre L. Identifying Missed Opportunities for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis at an Adolescent Health Center in the Deep South. J Adolesc Heal. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, Golin CE. Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2020. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1769834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randolph SD, Golin C, Welgus H, Lightfoot AF, Harding CJ, Riggins LF. How perceived structural racism and discrimination and medical mistrust in the health system influences participation in HIV health services for Black Women living in the United States South: A qualitative, descriptive study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2020;31(5):598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stacy ST, Castro KM, Acevedo-Polakovich ID. The Cost of Youth Voices: Comparing the Feasibility of Youth GO Against Focus Groups. J Particip Res Methods. 2020. doi: 10.35844/001c.13312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubov A, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. An Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills Model of PrEP Uptake. AIDS Behav. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister J, Zhang C, LeGrand S. Youth, Technology, and HIV: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0280-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordova D, Alers-Rojas F, Lua FM, et al. The Usability and Acceptability of an Adolescent mHealth HIV/STI and Drug Abuse Preventive Intervention in Primary Care. Behav Med. 2018. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2016.1189396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saberi P, Siedle-Khan R, Sheon N, Lightfoot M. The Use of Mobile Health Applications Among Youth and Young Adults Living with HIV: Focus Group Findings. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Wagner E. Youth as Partners, Participants or Passive Recipients: A Review of Children and Adolescents in Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Am J Community Psychol. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9533-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E, Bender K, Lengnick-Hall R, Yoshioka-Maxwell A, Rhoades H. Social Networking Technology Use and Engagement in HIV-Related Risk and Protective Behaviors Among Homeless Youth. J Health Commun. 2016. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1177139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borek N, Allison S, Cáceres CF. Involving vulnerable populations of youth in HIV prevention clinical research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e3627d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kegeles SM, Rebchook G, Tebbetts S, et al. Facilitators and barriers to effective scale-up of an evidence-based multilevel HIV prevention intervention. Implement Sci. 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0216-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quintiliani LM, Campbell MK, Haines PS, Webber KH. The use of the pile sort method in identifying groups of healthful lifestyle behaviors among female community college students. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2008;108(9):1503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denson N, Chang MJ. Racial diversity matters: The impact of diversity-related student engagement and institutional context. Am Educ Res J. 2009. doi: 10.3102/0002831208323278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veinot TC, Campbell TR, Kruger DJ, Grodzinski A. A question of trust: user-centered design requirements for an informatics intervention to promote the sexual health of African-American youth. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2013;20(4):758–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]