Abstract

Introduction

The volume of prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remains high, although the literature increasingly points to excessive prescribing in relation to guideline recommendations. No very recent data is available on the specific situation in Germany, particularly on the proportion of PPI consumption from over-the-counter (OTC) sales and self-selection, following PPI down-scheduling. The aim of this study was to determine the actual amount of prescribed and OTC PPIs in Germany.

Methods

For this retrospective study, several IQVIA databases were used, representing all prescriptions billed to statutory and private health insurers in Germany, as well as OTC sales. Analyses were performed for the period November 2020 to October 2021 or partially November 2018 to October 2021 and were descriptive in nature. Mainly, data were collected from IQVIATM PharmaScope National® as well as IQVIA TM DPM® databases.

Results

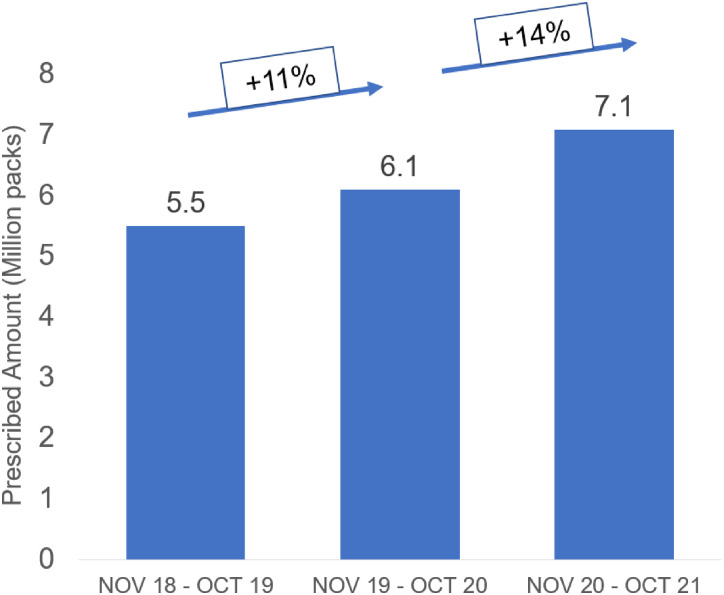

A total of 2.87 billion PPI tablets were shown to have been sold between November 2020 and October 2021, with most drugs prescribed in the largest packages and strengths. In addition, the OTC PPI market increased by an average of 14% per year over a 3-year period.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest the substantial size of the PPI market in Germany is based on prescriptions, a consistent increase in OTC PPI purchases and a recent increase in prescriptions.

Keywords: Proton pump inhibitors, PPI, over-the-counter, prescription

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been the leading therapy for upper gastrointestinal diseases, including gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastritis, for several decades. However, previous studies have shown that PPIs are often prescribed in the outpatient setting without intended indications or for longer than guidelines recommend for mild disease—with approximately 25% of patients on a PPI continuing to use them for at least 1 year.1,2 Furthermore, recent studies have suggested that many PPI prescriptions start in the hospital setting, where two-thirds of prescriptions have lacked an appropriate indication.2,3 With “appropriate use” being defined as the patient having a suitable indication (eg, GERD, Helicobacter pylori infection, etc) 4 and treatment duration (4-8 weeks). 5 Evidence of long-term PPI use with potential positive associations with chronic disease remains the domain of observational and cohort studies and it should be noted that these are largely well-tolerated drugs when used appropriately. 6 However, their widespread use, in refractory populations, those without reflux disease, or without appropriate indication introduces unnecessary risk where association has been reported. 6 In a prospective analysis conducted in China with 204 689 participants, regular use of PPIs was associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, and the risk increased with increasing duration of use. 7 The results of another retrospective, population-based cohort study in Taiwan, involving 56 785 PPI users and 56 785 controls, suggested that PPI use was associated with the risk of developing Parkinson's disease. 8 Zhang et al conducted a comprehensive literature search by including 6 studies with a total of 166 146 participants. Authors found a significant association between long-term PPI use and dementia risk in Europe among participants aged ≥65 years. 9 Recently, Ahn et al designed a real-world study with performance data from 7,696,127 individuals aged 40 years or older in Germany and supported the notion that PPI use is associated with increased dementia risk. 10 Guideline recommendations suggest rational use of PPIs at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible duration, and only in the presence of relevant indications5,11,12 A very recent study from the United Kingdom shows that the volume of PPI prescribing remains high, and there is increasing evidence in the literature that overprescribing is occurring in despite guideline recommendations.2,13 In response to growing evidence in this space, new updated GERD guidelines have been published in Germany to address this issue of overprescription and unnecessary prolonged PPI therapy, which resulted into a determined PPI therapy of 4 to 8 weeks for mild GERD indications, however, no recent data is available to illustrate the scale of PPI prescribing in Germany in a real-world, community setting, particularly considering recent down-scheduling of PPIs to over-the-counter (OTC) status. 5 The aim of this study was to determine the actual amount of prescribed and OTC PPIs in Germany.

Methods

For this retrospective study, several IQVIA databases were used, representing all prescriptions billed to statutory (SHI) and private health insurers in Germany, as well as OTC sales. Analyses were performed for the period November 2020 to October 2021 or partially November 2018 to October 2021 and were descriptive in nature. Mainly, data was collected from IQVIATM PharmaScope National® (PSN) as well as IQVIA TM DPM® (Der pharmazeutische Markt Deutschland) databases. The data in this repository was fully anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality, no information was used in this study that would compromise the privacy of any patient. Additionally the data was analysed and output into a digestible format by IQVIA, further assuring there were no opportunities for breach of patient confidentiality.

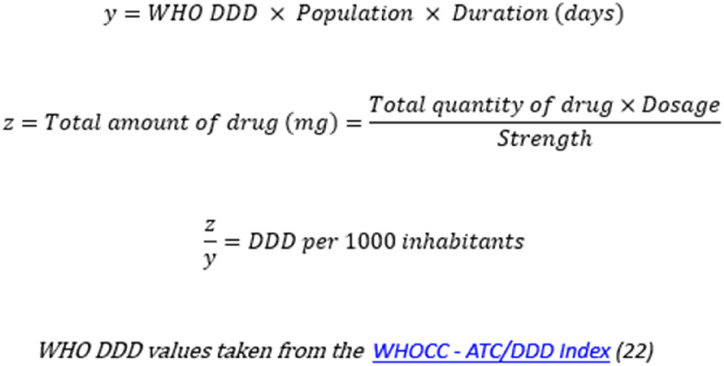

Additional analysis of results from Plehhova et al 14 was carried out due to the overlapping timeframe, dataset, and endpoints of the study, as it is closely related to this investigation. Calculations were made to ascertain the defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants/day in order to give the reader an idea of the level of prescription relative to population size (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Calculations made to determine defined daily dose per 1000 inhabitants/day.

IQVIATM PSN® data include pharmacy dispensing for the SHI market, private prescriptions, and cash sales based on public pharmacy dispensing. The data basis for the SHI market are SHI invoices issued by the pharmacy data centers. The estimate of private prescriptions and dispensing without a prescription was made based on a sample of around 6500 pharmacies. Market information on mail order comprises the purchases made by German consumers from mail order companies. A mail order panel forms the basis for this, which is supplemented by a projection. IMSTM DPM® provides information on the purchasing behavior of public pharmacies in Germany. The basis of the survey is a full survey of wholesalers, supplemented by a projection of direct sales by pharmaceutical manufacturers to pharmacies. It is a full wholesale survey and representative pharmacy sample.

Results

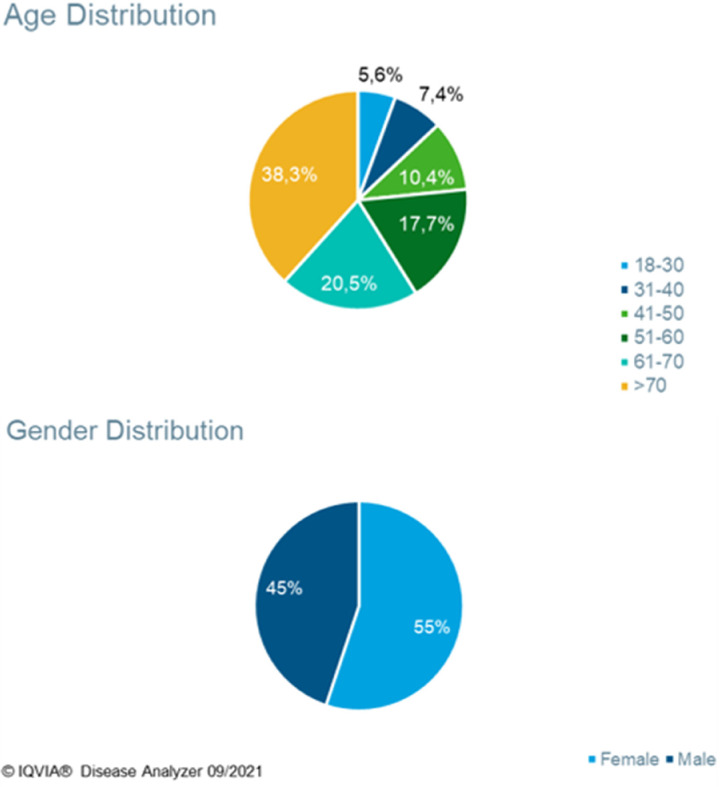

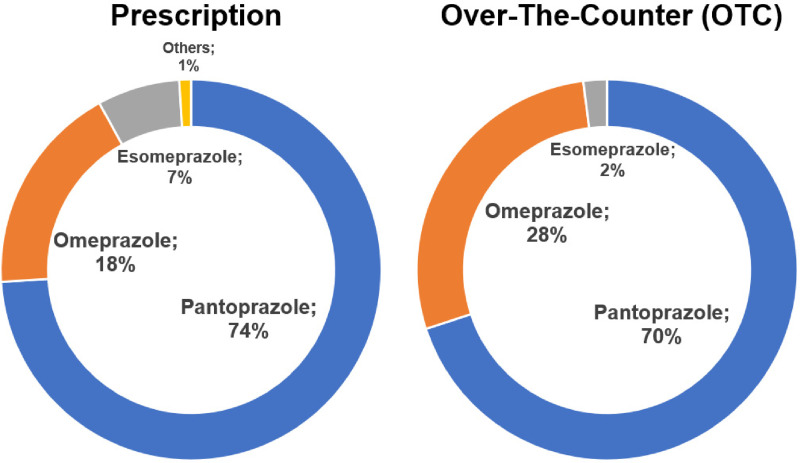

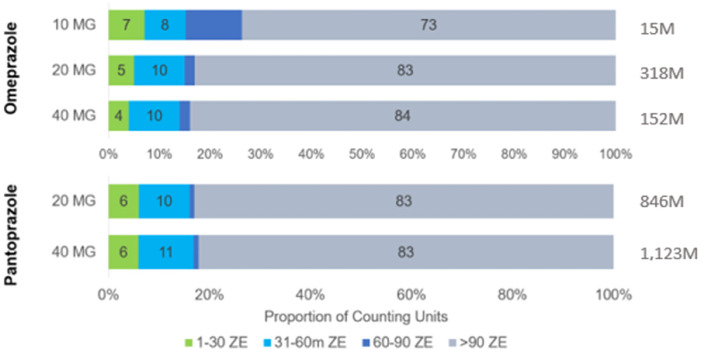

During the 1-year study period November 2020 and October 2021, 2.87 billion PPI tablets were sold, this is equivalent to approximately 34 PPI pills per German resident (based on a total population of 84.4 m as reported by the German Federal Office of Statistics in 2023) of which 97% were sold by prescription. Plehhova et al 14 covered the same location and a similar timeframe to this study; hence the demographics of its participants are alike. Analysis revealed a distribution that was highly skewed toward older patients but relatively even between men and women (Figure 2). 14 To gauge the number of PPIs sold to individuals, the number of DDD taken per 1000 inhabitants/day was calculated. The results of these calculations can be seen in Table 1, the highest result by a considerable margin was pantoprazole 40 mg at 16.9 DDD per 1000 inhabitants/day. A recent drug utilization study in Bavaria (2010-2018) showed even higher drug utilization figures (64.8 doses per 1000 insured people in Bavaria alone.) 15 Pantoprazole and omeprazole together accounted for 92% of prescription PPIs and 98% of OTC 16 (Figure 3). Most drugs were sold in the largest pack sizes of more than 90 tablets (eg, 83% of pantoprazole tablets) (Figure 4). In addition, 57% of pantoprazole packs and 31% of omeprazole packs were sold in the highest strength of 40 mg, which is equivalent to twice the DDD.

Figure 2.

Demographic makeup of PPI patients. 14 Abbreviation: PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Table 1.

Number of PPIs Prescribed to Patients Over the Study Period Separated by Medication and Dose. 14

| PPI | Dosage (mg) | DDD per 1000 inhabitants/day |

|---|---|---|

| Omeprazole | 20 | 4.8 |

| 40 | 4.6 | |

| Pantoprazole | 20 | 6.4 |

| 40 | 16.9 | |

| Esomeprazole | 20 | 0.8 |

| 40 | 3.0 |

Abbreviations: DDD, defined daily dose; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Breakdown by PPI active ingredients by channel: prescriptions against OTC. Abbreviations: PPI, proton pump inhibitor; OTC, over-the-counter.

Figure 4.

Package size breakdown for the 2 dominant PPIs: pantoprazole and omeprazole. Abbreviation: PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

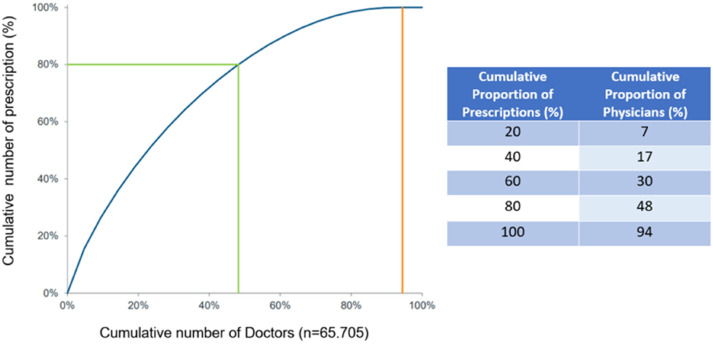

More than 93% of PPI prescriptions were made by physicians in private practice, primarily general practitioners (GPs). The prescribing market is very broad—94% of GPs prescribe PPIs—with a low level of concentration: 48% of GPs write 80% of prescriptions. Nevertheless, there are also frequent prescribers, with about 20% of physicians writing about 45% of total prescriptions (Figure 5). Ninety-five million PPI tablets were sold OTC; 96% of the OTC PPI market was for self-medication. The German OTC PPI market increased by an average of 14% per year over a 3-year period (+11% from 2019 to 2020, and +16% from 2020 to 2021, Figure 6). Although the prescription market was flat at a high level (+0.3% per year over 4 years through 2018), there was a decline in 2019 (−1.6%) that eventually reversed to 2.0% growth in 2020. Larger packages have proven more stable over time and are the most recent growth driver in reimbursement in the PPI prescription market.

Figure 5.

Concentration curve of PPI prescribers in Germany. Abbreviation: PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Figure 6.

Growth of the OTC PPI market in Germany during the period November 2018 to October 2021. Abbreviations: PPI, proton pump inhibitor; OTC, over-the-counter.

Discussion

This study found that there is a large PPI market in Germany, and it has actively grown in recent years. In addition, PPI became an OTC medicine in recent years, hence its distribution and consumption cannot be controlled by physicians. On the one hand, PPIs represent an important, safe, and efficacious therapy for numerous gastrointestinal diseases when used appropriately. On the other hand, it has been shown that unnecessarily prolonged PPI therapy is associated with an elevated risk of severe chronic diseases, even if no causal relationship has been proven. Our results indicate high level of PPI usage patients in Germany, however, this is not a purely German phenomenon. In addition to the UK study by Abrahami et al, 13 reference should be made to a review of overuse of medications in low- and middle-income countries. Authors included 367 studies reporting a total of 5.1 million prescriptions in 80 countries. The most commonly overused drug classes included antibiotics, psychotropic drugs, PPIs, and antihypertensives, while the main reasons were limited knowledge of side effects, polypharmacy, poor regulation, and financial influences. Overuse of PPIs was reported in 53 of these studies. 17 Given the DDD calculations demonstrated in Table 1, it is clear that high levels of PPI usage are common in regions such as Bavaria in addition to Germany as a whole. What this table shows specifically is that there seems to be a preference for large pack sizes, which is trend mirrored in this study (Figure 4). The combination of large pack sizes with high relative usage rates is concerning due to the risk of potential uncontrolled use where patients may be issued more pills than is indicated. Furthermore, consideration should be paid to potential side effects from long-term PPI usage, particularly given the high median age of patients receiving these drugs.

New updated GERD guidelines have been published in Germany to address the issue of overprescription and unnecessarily protracted PPI therapy, resulting in a prescribed PPI usage duration of 4 to 8 weeks for mild GERD indications. However, no recent data is available to illustrate the scale of PPI prescription in Germany in a real-world, community setting, particularly considering the recent down-scheduling of PPIs to OTC status. Following the old guidelines, If GERD was suspected due to typical reflux symptoms; prescription of empirically dosed PPI was given. Concerning typical reflux syndrome with unknown endoscopy findings, treatment with a PPI was carried out on an ad hoc basis after successful acute therapy with no limits in duration. 18 The new treatment guideline is different in that it recommends long-term drug management to be in response to established symptoms to avoid overtreatment and establish appropriate use. The restriction of PPI therapy to a maximum treatment period of 8 weeks lead the authors of this guideline to include a strong statement urging the discontinuation of the PPI treatment if it is no longer deemed necessary on the basis of symptoms and the potential for adverse effects from long-term use. 5 Furthermore, they state that in a prospective, open-label study, which included 6249 patients with dyspepsia and long-term PPI therapy after training and taking an alginate for breakthrough symptoms, 75.1% of patients were able to reduce the dose or discontinue therapy within 1 year, with 40.3% of this group discontinuing PPI treatment. 19

A recent analysis of PPI prescriptions in Germany by Plehhova et al, 14 focusing on a population of 472 156 patients over a period overlapping with this study (January 2018-September 2021), reported that the average PPI treatment episode was 141 days, with a median treatment duration of 95 days and 36.6% of patients being treated with PPIs for >6 months. They also found conditions such as gastritis and duodenitis (47.2%) and reflux diseases (38.4%) were more frequently associated with PPI prescriptions. 14

Plehhova et al 14 found that PPI prescription differs widely between guideline recommendations, with only 4.5% of patients in a sample of 472 156 were receiving PPI therapy fully in line with guidance. This small group, defined as “Patients with an appropriate PPI prescription” were 1 of 6 groups identified. Some others included “Patients whose PPI dosage can be reduced” and “Patients for whom PPIs are no longer necessary,” these being the largest groups at 92% and 62%, respectively. While these groups did overlap, as some patients belonged to multiple cohorts, the large number of patients in each clearly indicate the frequency inappropriate PPI prescription.

Regarding large pack sizes (in some cases 3 months of tablets), the data analyzed in this study was influenced by ongoing restrictions deriving from recommendations during the pandemic to limit doctor visits, which resulted in greater frequency of large pack prescriptions. As for the potential misuse of large pack sizes, it is illegal to resell Rx products in the German market, additionally; due to the pricing structure, it would make little sense to resell PPI, as they are relatively cheap.

The most common conditions for which PPIs are prescribed are gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, and eradication of H. pylori. 1 In the case of H. pylori eradication, combination therapy with antibiotics is usually given to kill H. pylori. 20 However, immediate initiation of PPIs is not always appropriate. It is recommended to start a gradual dose reduction before discontinuing PPIs and to administer H2 receptor antagonists or antacids at the same time. This gradual approach may allay patients’ fears of a return of symptoms and gain patients’ confidence and improve outcomes by bringing patients into the discontinuation decision-making process.2,6 Del-Pino & Sanz conducted a narrative review to evaluate PPI discontinuation strategies performed exclusively or in collaboration with primary care and to identify factors that might influence the success of these strategies. They concluded that the clarity and simplicity of the de-escalation protocols, in which patients were informed of the actions to be taken in the event of symptom recurrence, and the training of clinicians responsible for de-escalation were the 2 most important factors. 21

Our study is one of the first in Germany to consider market research analyses on PPI consumption not only in their clinical context, but in a whole, real-world population rather than regarding a single population as hospital discharge patients. The use of databases with partial and full coverage of pharmacy data centers or wholesalers and simultaneous analysis of prescriptions and OTC dispensing as well as physicians are the main strengths of these studies.

Limitations

Being a wide-scale, market research analysis study, this study also has its limitations, such as the lack of hypothesis-testing statistical procedures and the lack of information on diagnoses, thus the possibility to distinguish between necessary and non-necessary PPI therapy. This study aims to assess overall trends in PPI consumption (both through healthcare channels and OTC, where they are not controlled by physicians), and should be considered as a scale supplement to more tightly controlled studies assessing prevalence.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate the substantial size of the PPI market in Germany (based on prescriptions) and a consistent increase in OTC PPI purchases and a recent increase in prescriptions. Further studies are needed, however this study supports the importance of the new guidelines recently introduced in Germany and the need for measures to regulate the excessive use of PPIs by patients.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Lucas R. Jacobs who provided medical writing support.

Author Biographies

Kate Plehhova, MChem, is Senior Manager of Medical Sciences (GI) at Reckitt Benckiser. Her research focuses on mild and moderate disease in gastroenterology, with a focus on appropriate reflux management in the primary and secondary care setting.

Monika Häring is Medical Sciences Lead (DACH region) for Reckitt Benckiser, with a focus on OTC medicines.

Joshua Wray, MChem, is Manager of Medical Sciences at Reckitt Benckiser. His research focuses on mild and moderate disease in gastroenterology, with a focus on IBS.

Cathal Coyle is the Medical Science Director for Digestive Health at Reckitt. He holds a BSc in Biomedical Sciences, a PhD in reflux pathophysiology, as well as a series of post-doctorates and a research fellowship in the same area. He has worked with Reckitt for 16 years and has been in his current role for 4 years.

Karel Kostev is an expert in Epidemiology across multiple healthcare fields. He is a Lecturer at University Hospital Marburg and is also the Senior Scientific Principal at IQVIA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: KK collated the results and reviewed the manuscript. KP, MH, JW, and CC oversaw the study, and wrote the manuscript.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KP, MH, JW, CC, and LJ are employees of Reckitt Benckiser. KK is the employee of IQVIA.

Ethics Approval: The database used includes only anonymized data in compliance with the regulations of the applicable data protection laws. German law allows the use of anonymous electronic medical records for research purposes under certain conditions. According to this legislation, it is not necessary to obtain informed consent from patients or approval from a medical ethics committee for this type of observational study that contains no directly identifiable data. Because patients were only queried as aggregates and no protected health information was available for queries, no Institutional Review Board approval was required for the use of this database or the completion of this study.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by Reckitt Benckiser.

ORCID iD: Karel Kostev https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2124-7227

Data Availability Statement: Data generated at IQVIA, available upon request.

References

- 1.Heidelbaugh JJ, Kim AH, Chang R, Walker PC. Overutilization of proton-pump inhibitors: what the clinician needs to know. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(4):219–232. doi: 10.1177/1756283x12437358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Targownik LE, Fisher DA, Saini SD. AGA clinical practice on de-prescribing proton pump inhibitors: expert review. Gastroeneterology. 2022;162:1334–1342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubert CE, Blum MR, Gastens V, et al. Prescribing, deprescribing and potential adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors in older patients with multimorbidity: an observational study. CMAJ Open. 2023;11(1):E170–E178. doi: 10.9778%2Fcmajo.20210240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savarino V, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, et al. The appropriate use of proton-pump inhibitors. Minerva Med. 2018;109(5):386–399. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.18.05705-1. Epub 2018 May 31. PMID: 29856192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madisch A, Koop H, Miehlke S, et al. S2k-Leitlinie Gastroösophageale Refluxkrankheit und eosinophile Ösophagitis der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS): s.l. : DGVS, 2023. [cited 17 July 2023]. LL-Reflux_Leitlinie_final_13.03.23.pdf (dgvs.de).

- 6.Savarino E, Anastasiou F, Labenz J, Hungin APS, Mendive J. Holistic management of symptomatic reflux: rising to the challenge of proton pump inhibitor overuse. BJGP. 2022;72(724):541–544. doi: 10.3399/bjgp22x721157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan J, He Q, Nguyen LH, et al. Regular use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective cohort studies. Gut. 2021;70(6):1070–10776. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HL, Lei WY, Wang JH, Bair MJ, Chen CL. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk for Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(19):e33711. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000033711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Liang M, Sun C, et al. Proton pump inhibitors use and dementia risk: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(2):139–147. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02753-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn N, Wawro N, Baumeister SE, et al. Time-varying use of proton pump inhibitors and cognitive impairment and dementia: a real-world analysis from Germany. Drugs Aging. 2023. doi: 10.1007/s40266-023-01031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell B, Lass E, Moayyedi P, Ward D, Thompson W. Reduce unnecessary use of proton pump inhibitors. Br Med J. 2022;379. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NICE. Dyspepsia—proven GORD. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. [online] December 2022. [cited 17 July 2023]. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/dyspepsia-proven-gord/.

- 13.Abrahami D, McDonald EG, Schnitzer M, Azoulay L. Trends in acid suppressant drug prescriptions in primary care in the UK: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e041529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plehhova K, Haering M, Wray J, Coyle C, Ibáñez E, Kostev K. Prescribing patterns of proton pump inhibitors in Germany: a retrospective study including 472146 patients. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14. doi: 10.1177/21501319231221002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rückert-Eheberg IM, Nolde M, Ahn N, et al. Who gets prescriptions for proton pump inhibitors and why? A drug-utilization study with claims data in Bavaria, Germany, 2010-2018. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;78(4):657–667. doi: 10.1007/s00228-021-03257-z. Epub 2021 Dec 8. PMID: 34877614; PMCID: PMC8927002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DSTATIS, Statistisches Bundesamt, Press release No.235. 20 June 2023 [cited 17 July 2023]. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2023/06/PE23_235_12411.html

- 17.Albarqouni L, Palagama S, Chai J, et al. Overuse of medications in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Bull World Health Organ. 2023;101(1):36–61D. doi: 10.2471/blt.22.288293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koop H, Fuchs KH, Labenz J, et al. Gastroösophageale Refluxkrankkheit unter Federführung Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS). May, 2014 v14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Coyle C, Symonds R, Allan J, et al. Sustained proton pump inhibitor deprescribing among dyspeptic patients in general practice: a return to self-management through a programme of education and alginate rescue therapy. A prospective interventional study. BJGP Open. 2019;3(3):bjgpopen19X101651. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen19X101651. PMID: 31581112; PMCID: PMC6970585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, Hibi T. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(4):639–648. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del-Pino M, Sanz EJ. Analysis of deprescription strategies of proton pump inhibitors in primary care: a narrative review. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2023;24:e14. doi: 10.1017/s1463423623000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Updated 26 January 2024 [Cited 26 January 2024]. https://www.whocc.no/ATC_ddd_index/?code=A02BC