Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the impact of abortion legislation on mental health during pregnancy and postpartum and assess whether pregnancy intention mediates associations.

Methods:

We quantified associations between restrictive abortion laws and stress, depression symptoms during and after pregnancy, and depression diagnoses after pregnancy using longitudinal data from Nurses’ Health Study 3 in 2010–2017 (4,091 participants, 4,988 pregnancies) using structural equation models with repeated measures, controlling for sociodemographics, prior depression, state economic and sociopolitical measures (unemployment rate, gender wage gap, Gini index, percentage of state legislatures who are women, Democratic governor).

Results:

Restrictive abortion legislation was associated with unintended pregnancies (β=0.127, p=0.02). These were, in turn, associated with increased risks of stress and depression symptoms during pregnancy (total indirect effects β=0.035, p=0.03; β=0.029, p=0.03, respectively, corresponding <1% increase in probability), but not after pregnancy.

Conclusions:

Abortion restrictions are associated with higher proportions of unintended pregnancies, which are associated with increased risks of stress and depression during pregnancy.

Keywords: abortion policy, Perinatal health, mental health, Women’s health, mediation

Introduction

Adverse mental health, particularly depression, is not only a common complication of pregnancy but also a leading contributor to pregnancy-related mortality.1 Parental experiences of adverse mental health, both during and after pregnancy, lead to reduced parent-child bonding,2 which can result in developmental and behavioral problems for the children.3 Approximately 13% of birthing parents experienced depression symptoms after pregnancy across the U.S. in 2018, but prevalence varies widely by state of residence, ranging from 10% (Illinois) to 24% (Mississippi).4

One critical predictor of antepartum and postpartum (henceforth, “perinatal”) mental health is pregnancy intention. People with unintended (i.e., unwanted or mistimed) pregnancies are estimated to have more than twice the risk of depression during and after pregnancy compared to people with intended pregnancies.5,6 These effects can persist beyond the postpartum period—in one cohort, those who carried unintended pregnancies to term had a 40% increase in having a depression episode later in life relative to those with intended pregnancies.7

Since the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, and even before the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, states have increasingly passed legislation restricting abortion. Restrictive legislation includes mandatory waiting periods between an intake appointment and a procedure; two-visit laws requiring patients to be in the clinic at least once before the procedure day; minor consent laws requiring approval from one or both parents; mandatory ultrasounds; funding restrictions; and provider license barriers or onerous building regulations. Such laws have led to abortion facilities closing, increased wait times, restrictions on types of abortion care provided in facilities, and other barriers to abortion care for those seeking abortions, leading ultimately to a reduction in abortions.8 As a result, people carrying unintended pregnancies are more likely to carry their pregnancies to term as state abortion laws become more restrictive.9

Given the links between unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression, the geographic variation in both perinatal mental health and abortion legislation, and recent increases in restrictive abortion policies, it is critical to examine the role of restrictive abortion legislation in exacerbating adverse perinatal mental health. Emerging research has begun to elucidate these relationships but has several limitations. For example, research using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System reveals that people living in states without public funding for abortion have increased risks for postpartum depression.10 However, evaluating the impact of a single policy has limited public health impact, given that multiple policies are often enacted simultaneously as part of a larger bill—as a result, variation in individual laws may be less salient to health outcomes than variation in state abortion policy climate. More recently, ecological data have demonstrated that abortion restrictions are linked to a 6% increase in state-level suicides among women of reproductive age.11 Crucially, the ecological design precluded examination of individual-level data (e.g., depression) or potential mediators and no study to date has examined the relationship between state-level abortion laws and mental health during pregnancy, nor examined the role of pregnancy intention.

In the present study, we examined the association between state-level abortion legislation and the risk for adverse perinatal mental health, as well as whether these associations are mediated by pregnancy intention. We used data from the Nurses’ Health Study 3, a cohort of primarily non-Hispanic White healthcare workers who were surveyed both during their second trimester and in the postpartum. We hypothesized that more restrictive abortion policy climates would be associated with a higher proportion of unintended pregnancies and that unintended pregnancies, relative to intended pregnancies, would be associated with higher risks of adverse perinatal mental health outcomes.

Methods

Sample.

We examined data from pregnancies reported in the Parental Health Sub-study (PHS) within the Nurses’ Health Study 3 (NHS3).12 NHS3 participants include adult nurses and nursing students born in or after 1965, living in the U.S. or Canada. Initial questionnaires were administered in 2010 and enrollment is ongoing. Participants complete online questionnaires every six months. If participants report a current pregnancy, they are invited to participate in the PHS; this sub-study consists of two questionnaires, first during their second trimester (~20–25 weeks gestation) and next ~5 weeks postpartum. Participants were included in the current analysis if they reported pregnancies between 2010–2017 (from study baseline to the last year of our policy index, described below), participated in the pregnancy sub-study, and lived in one of the 50 U.S. states while pregnant (N=4,091 participants with N=4,988 pregnancies).

We examined three self-reported perinatal mental health-related outcomes: perceived stress, depression symptoms, and postpartum depression diagnosis. Perceived stress was assessed on the pregnancy survey. Postpartum depression diagnosis was assessed on the postpartum survey. Depression symptoms were assessed on both surveys, i.e., during pregnancy as well as in the postpartum period. Perceived stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale, summed over 4 items assessing feelings of stress and lack of control via a 5-point Likert scale; this outcome was dichotomized with a cutoff of ≥6 indicating high stress.13 Depression symptoms were measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, ten items asking about past-week feelings were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (range: 0–30), dichotomized with a cutoff of ≥9 to indicate depression symptoms.14 We chose this cutoff because in validation studies it has been shown to be highly sensitive for detecting depression symptoms, particularly in marginalized populations;15 however, given that other cutoffs have been examined in the perinatal mental health literature, we examine depression symptoms at less sensitive cutoffs (≥11 and ≥13) in sensitivity analyses to detect more severe symptoms.16

Finally, participants self-reported postpartum depression diagnosis after delivery (dichotomized as yes/no).

Our exposure was abortion policy climate which we measured using an abortion-policy index developed by NARAL Pro-Choice America and made available by Zandberg et al (2022).11 This index captures variation by year and by state from 2006–2017 and includes 17 policies that either restrict abortion access (e.g., mandatory delays, parental consent laws) or support abortion access (e.g., state constitutional protections for abortion rights). A higher score represents a more restrictive environment, and possible scores ranged from −7 (most supportive, e.g., California in 2015) to 12 (most restrictive, e.g., North Dakota in 2017). Because laws were frequently passed together and are highly collinear, we mean-standardized this index such that a value of zero represented the average index score (a value of 3), and a 1-unit increase represented a one standard deviation change in the index (a value of 4), consistent with previous work.17 Because state-level abortion legislation is often not implemented until the year after it is passed, the policy index was lagged by a single year to represent the concurrent policy climate at the time of conception and pregnancy—i.e., if a participant was surveyed in 2012, we coded their policy exposure as that state’s policy climate in 2011, consistent with prior work.17 Supplemental Figure 1 shows the exposure distribution across states. We then linked the index to participants’ state of residence during the pregnancy questionnaire.

The mediator of interest was pregnancy intention, which was measured during pregnancy. We coded pregnancies as intended if the participants endorsed either “I was actively trying to become pregnant” or “I was not actively trying, but I was glad to become pregnant”; we coded pregnancies as unintended if participants endorsed either “I wanted to be pregnant someday, but not now” or “I did not want to be pregnant now or at any time in the future.”

For tests of the direct effects of state abortion policy climate on perinatal mental health, we identified state-level confounders that are common causes of abortion policy climate and adverse mental health outcomes. Because state-level economic deprivation influences health policy and mental health,18 we controlled for state-level unemployment rate and income inequality—operationalized as the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality ranging from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). To isolate the impact of restrictive abortion legislation from other sources of gender-based inequality (which also impacts women’s mental health19), we controlled for the gender-based wage gap, calculated as the ratio between men’s and women’s median earnings for each state in each year. Because state-level political and gender composition of legislators are causes of abortion policy implementation and may be related to depression, we included a measure of the percentage of state legislatures who were women, and whether the state had a Democratic governor.19,20 Economic indicators were drawn from the American Community Survey and Current Population Survey; political representation data were from the University of Michigan Institute for Public Policy and Social Research.

In mediation models, we further controlled for pregnancy- and individual-level covariates that were common causes of pregnancy intention and adverse mental health. Pregnancy-level covariates included: age at pregnancy (continuous) and depression symptom history dichotomized as yes/no based on the question: “Before this pregnancy, was there ever a period of time when you were feeling depressed or down or when you lost interest in pleasurable activities most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks?” To account for the possibility of reverse causation between prior depression symptoms and current depression symptoms (given that they were assessed at the same time point), we controlled for baseline depression history in sensitivity analyses. We chose to use the pregnancy-level measure, rather than the baseline measure, in main analyses for two reasons; first, because the pregnancy-level measure was asked at every pregnancy, allowing the depression history to vary throughout the study as participants reported more pregnancies; second, because the baseline measure was assessed using a select-all-that-apply question stem, so we were unable to delineate between a response of “no depression” and item missingness.

Individual-level covariates included: race/ethnicity, (dichotomized as non-Hispanic White or not) and marriage status (partnered vs. not partnered), both assessed in the baseline NHS3 questionnaire. We chose to control for race/ethnicity, rather than examine moderation; while race and ethnicity are not themselves causes of disparate health, individuals who belong to a minoritized racial or ethnic group disproportionately experience individual-, interpersonal-, and structural-level minority stressors (e.g., racism, xenophobia) which lead to systematically worse pregnancy outcomes,21 including adverse perinatal mental health22 and unintended pregnancies.23–25 Race and ethnicity also shape states of residence due to racism and xenophobia shaping access to resources, as well as historical and contemporary immigration patterns—thus, belonging to a minoritized racial or ethnic group is likely associated with the state-level policy exposure. Because of the composition of the sample (>90% non-Hispanic White), we were unable to examine moderation; therefore, to understand the average impact of this legislation on the study sample, we chose to control for race and ethnicity. In sensitivity analyses, we show models without adjustment for race and ethnicity.

The unit of analysis was the pregnancy. We modeled direct and indirect associations using structural equation modeling with clustering at the individual-level to account for repeated observations. Supplemental Figure 2 shows a directed acyclic graph of associations being tested and confounder control for each. We first tested direct associations between abortion policy climate and each outcome in separate models (“c” paths), with control for state-level covariates; we next tested associations between abortion policy climate and pregnancy intention (“a” path) with control for state-level covariates; we then tested associations between pregnancy intention and each outcome, additionally controlling for individual- and pregnancy-level covariates. Finally, we modeled all paths using structural equation models using the “lavaan” package in R, which was developed to fit latent statistical models and path analysis models (including structural equation models).26 We modeled each outcome and pregnancy intention dichotomously using weighted least squares regression with a probit distribution; coefficients are interpreted as a change in the outcome’s z-score in response to a 1 standard deviation change in the lagged abortion policy climate.

Of the 4,988 eligible pregnancies, 3,941 (79%) had fully observed data for all individual and pregnancy-level covariates. The most common sources of missingness were mental health outcomes assessed after pregnancy; 15% of pregnancies were missing data on depression symptoms after pregnancy, and 14% were missing data on depression diagnosis after pregnancy. We imputed missing data using the “Amelia”27 package in R. This package imputes missing data using expectation maximization with bootstrapping, and it can account for repeated measures and clustering. We imputed 10 missing data sets and combined all estimates using Rubin’s Rules, the most commonly used method for pooling mean values of estimated parameters from models from multiple imputed data sets and for pooling standard errors based on both within-imputation and between-imputation variance.28

We conducted three additional analyses to confirm the robustness of our findings. To account for the potential violations of time-varying mediation assumptions due to repeated measures, we examined associations restricting to first pregnancies. Next, we conducted a specificity analysis with a negative control outcome29 to rule out spurious findings due to unmeasured state-level confounding factors. Specifically, we examined the associations between state abortion policy climate and a pregnancy-related health outcome that is theoretically unrelated to that legislation, namely, urinary tract infections, assessed after pregnancy via self-report on the same questionnaire as depression symptoms.

Finally, we were concerned about reverse causation between the mediator and the outcome; namely, that feelings of depression symptoms may lead participants to (inaccurately) appraise their pregnancy as unintended.30 To determine the extent of the bias, we examined pregnancy intention on pre-conception surveys. On online questionnaires given every 6 months, participants were asked if they were currently pregnant; if so, they were recruited to the PHS. If not, they were asked if they were trying to become pregnant or thought they might become pregnant in the next 12 months, with answer choices consisting of “No”; “Yes, actively trying”; or “Yes, may become pregnant within the next year.” Among those who reported mistimed or unwanted pregnancies on the PHS, we examined surveys in the prior 12 months to understand if, before conception, they reported that they were actively trying. We did not use these preconception measures in the main model for three reasons; first, for over 50% of pregnancies (N=2,904), preconception intention was missing due to either existing pregnancy at the time of the survey (leading to skip logic) or item non-response. Second, this measure did not appraise intention at the same level of detail as the one in the PHS. Third, while we could only meaningfully assess intendedness at the time of pregnancy (i.e., on the PHS) rather than before participants were pregnant, we believe that how participants felt during the pregnancy may be more relevant to this specific research question. Pregnancy intention is a debated concept and has important limitations, including that many people are ambivalent about pregnancy. Many researchers have called for measures of pregnancy acceptability, i.e., to what extent a pregnancy is acceptable once the participants learned they were pregnant.31 In the context of this research question, acceptability may be a more meaningful measure for understanding the complexity of feelings associated with an actual pregnancy, rather than a hypothetical future pregnancy.31,32 Acceptability, regardless of preconception intention, is itself an important predictor of perinatal mental health.33 However, measures of pregnancy acceptability were not available at the time the cohort surveys were developed. Nevertheless, while the measure of pregnancy intention used in this study may not accurately assess preconception intention, it may better reflect how participants feel about their pregnancy at the time of their pregnancy.

The study protocol was approved by the Partners Healthcare and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute Institutional Review Boards.

Results

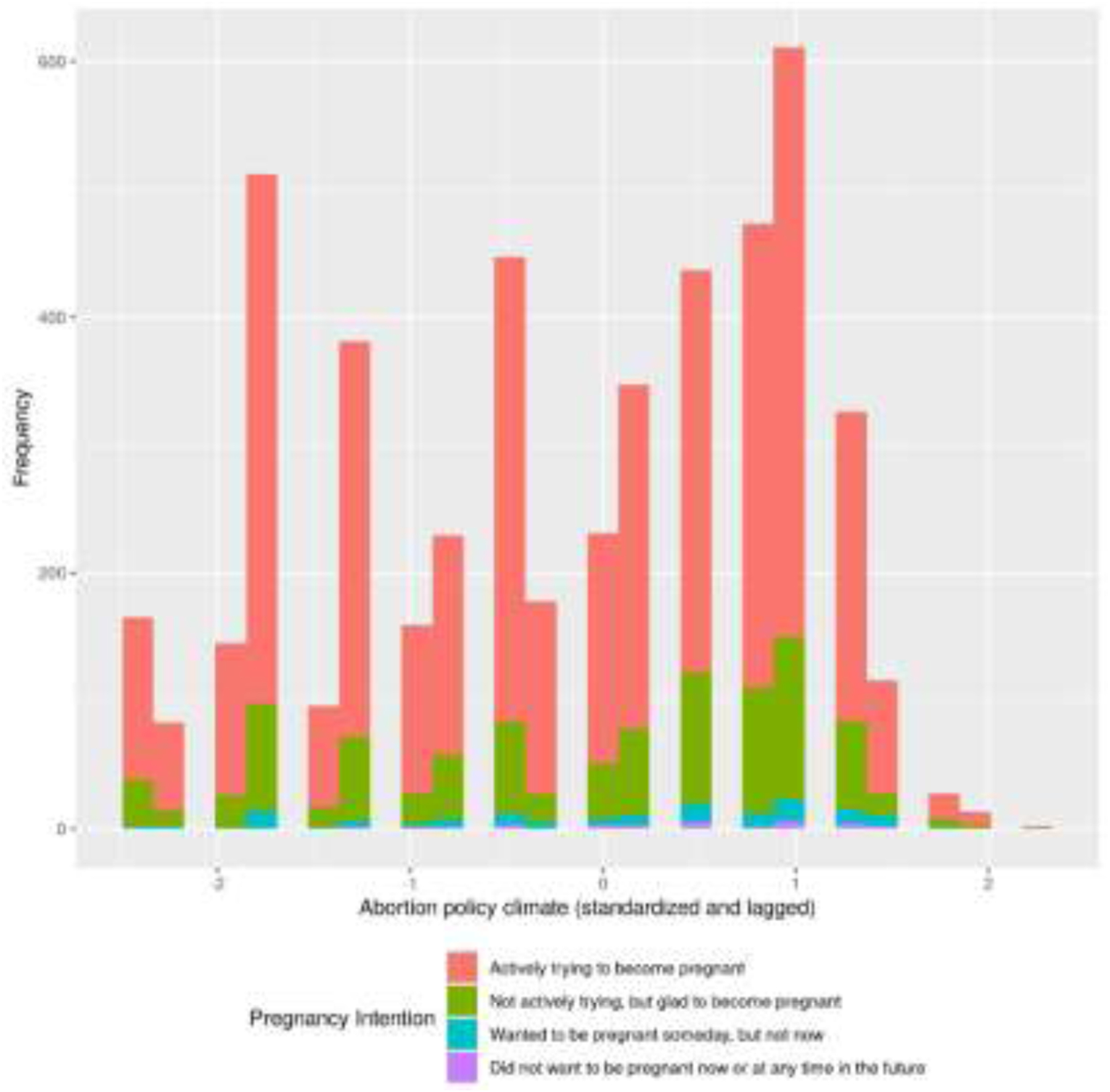

Table 1 shows the distribution of study outcomes and covariates across all observed pregnancies, stratified by pregnancy intention. Most pregnancies (N=3,881, 78%) were intended. Relative to those with unintended pregnancies, those with intended pregnancies reported markedly lower risks of stress and depression symptoms during pregnancy, as well as postpartum depression diagnoses. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the abortion policy climate indices within the analytic sample, stratified by pregnancy intention; the mean index was −0.22, with a range of −2.46 (maximally supportive) to 2.21 (maximally restrictive).

Table 1:

Distribution of key study variables by pregnancy intention among 4,988 pregnancies to participants in the NHS3, 2010–2017

| Intended | Unintended | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actively trying to become pregnant | Not actively trying, but glad to become pregnant | Wanted to be pregnant someday, but not now | Did not want to be pregnant now or at any time in the future | |

| (N=3,881 pregnancies) | (N=942 pregnancies) | (N=125 pregnancies) | (N=30 pregnancies) | |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age at pregnancy, mean years (SD) | 32.2 (3.8) | 32.1 (4.2) | 31.2 (3.7) | 36.6 (4.9) |

| Married at baseline survey, n(%) | 1,086 (28.0%) | 245 (26.0%) | 38 (30.4%) | 7 (23.3%) |

| Non-Hispanic White, n(%) | 3,566 (91.9%) | 851 (90.3%) | 111 (88.8%) | 29 (96.7%) |

| Depression measures | ||||

| Reported depression prior to this pregnancy, n(%) | 2443 (35.7%) | 585 (37.3%) | 80 (35.2%) | 15 (50.0%) |

| High perceived stress, n(%) | 740 (19.1%) | 256 (27.2%) | 53 (42.4%) | 11 (36.7%) |

| Depression symptoms during pregnancy, n(%) | 623 (16.1%) | 211 (22.4%) | 40 (32.0%) | 12 (40.0%) |

| Depression symptoms after pregnancy, n(%) | 527 (13.6%) | 137 (14.5%) | 30 (24.0%) | 4 (13.3%) |

| Diagnosed with postpartum depression, n(%) | 128 (3.3%) | 51 (5.4%) | 6 (4.8%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| State policy, equality, and socioeconomic measures | ||||

| Restrictive abortion policy index (standardized), mean (SD) | −0.2 (1.2) | −0.1 (1.2) | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.8) |

| State unemployment rate, mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.8) | 6.2 (1.8) | 6.2 (1.9) | 6.0 (1.6) |

| State Gini index, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.0) |

| Percentage of state legislators who are women, mean (SD) | 25.0 (5.6) | 24.5 (5.8) | 24.2 (6.3) | 22.8 (4.6) |

| Living in a state with a Democratic governor, n(%) | 1,871 (48.2%) | 410 (43.5%) | 50 (40.0%) | 10 (33.3%) |

| State gender wage gap, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) |

Note: For descriptive statistics, eligible sample shown prior to imputing missing. All regression analyses were performed on imputed data.

Figure 1:

Distribution of state-level abortion policy climate, grouped by pregnancy intention, n=4,988 pregnancies to participants in the NHS3, 2010–2017

Policy climate represented standardized, lagged score of 17 policies that either restrict abortion access (e.g., mandatory delays, parental consent laws) or support abortion access (e.g., state constitutional protections for abortion rights). A higher score represents a more restrictive environment, and a 1-unit increase represents a one standard deviation change in the index.

In unmediated models, abortion policy climate was unrelated to high stress during pregnancy, depression symptoms during or after pregnancy, or depression diagnosis after pregnancy (Table 2, Column 1). However, abortion policy climate was positively associated with the proportion of unintended pregnancies compared to intended pregnancies (β=0.127, standard error [SE]=0.053, p=0.02), adjusting for state-level confounders. Unintended pregnancies were significantly associated with high stress (β=0.610, SE=0.110, p<0.01), depression symptoms during pregnancy (β=0.511, SE=0.115, p<0.01), and depression symptoms after pregnancy (β=0.274, SE=0.126, p=0.03), controlling for individual- and pregnancy-level confounders. However, unintended pregnancies were not associated with risks of depression diagnosis after pregnancy (β=0.090, SE=0.199, p>0.10).

Table 2:

Associations between abortion policy climate and antepartum and postpartum mental health among 4,988 pregnancies to participants in the NHS3, 2010–2017

| Outcome | Direct effects without mediator (c) β (SE) | Controlled direct effects with mediator (c’) β (SE) | Indirect effects through pregnancy intention (ab) β (SE) | Total effects (controlled direct and indirect) β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High stress | −0.011 (0.028) | −0.037 (0.031) | 0.035 (0.016)** | −0.002 (0.029) |

| Depression symptoms during pregnancy | 0.032 (0.029) | 0.015 (0.032) | 0.029 (0.014)** | 0.044 (0.030) |

| Depression symptoms after pregnancy | −0.044 (0.032) | −0.049 (0.033) | 0.016 (0.010) | −0.032 (0.033) |

| Depression diagnosis after pregnancy | −0.022 (0.047) | −0.016 (0.050) | 0.004 (0.012) | −0.011 (0.049) |

Note:

p<0.05;

model estimates are adjusted for state-, individual-, and pregnancy-level covariates

Table 2 shows results from structural equation models examining mediation. While direct effects between abortion policy climate and each outcome remained null (Table 2, Column 2), indirect effects through pregnancy intention (Table 2, Column 3) were observed to mediate the relationship between abortion policy climate and high stress during pregnancy (β=0.035, SE=0.016, p=0.03) and depression symptoms during pregnancy (β=0.029, SE=0.014, p=0.03). Given the sample prevalence of high stress (21%, SE=0.01) and depression symptoms during pregnancy (18%, SE=0.01), each of these increases is equivalent to a less than 1% increase in probability of the outcomes. We saw no mediation of the relationship between abortion policy climate and depression symptoms nor depression diagnosis after pregnancy through pregnancy intention (β=0.016, SE=0.010, p=0.12; β=0.004, SE=0.012, p=0.71, respectively).

In the negative control analysis, as anticipated, abortion policy climate was unrelated to urinary tract infections (controlled direct effects β=−0.004, SE=0.042; indirect effects through intention β=0.012, SE=0.009, p=0.17; total effects β=0.008, SE=0.041). Results from sensitivity analyses among first pregnancies, using baseline depression as a control variable, without control for race and ethnicity, and exploring different cut-offs for depression scoring are shown in Supplemental Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. These estimates did not meaningfully vary in magnitude or interpretation from the main analyses.

Finally, we compared preconception pregnancy intention to PHS-reported pregnancy intention among those who endorsed unintended pregnancies to assess the risk of reverse causation. Among 155 pregnancies reported as unwanted/mistimed in the PHS, only 4 (2.5%) participants endorsed trying to get pregnant in preconception surveys, and only 1 of those reported depression symptoms during pregnancy, suggesting limited evidence that the study findings are attributable to bias resulting from reverse causation.

Discussion

This study examined how state-level restrictive abortion climate shapes mental health during and after pregnancy in a cohort of nurses. We found evidence that increases in adverse reproductive climate were associated with higher proportions of pregnancies that were unintended, subsequently leading to higher risks of stress and depression symptoms during pregnancy, consistent with our hypotheses. While the magnitude of these increases was small—i.e., less than 1% increased risk in sample—we interpret these as clinically meaningful increases in adverse perinatal mental health during pregnancy in this sample. However, inconsistent with our study hypotheses, we saw no evidence of a direct effect between restrictive abortion legislation and any study outcome, nor did mediation through intention reach statistical significance for depression outcomes assessed after pregnancy.

We interpret these findings to mean that pregnant people in restrictive abortion climates have small but meaningful increased risks in depression and stress during pregnancy when those pregnancies are unwanted or mistimed. Consistent with prior research,17 these findings suggest that restrictive abortion legislation is burdensome to pregnant people, including by resulting in more unintended pregnancies. Compared to intended pregnancies, unintended pregnancies lead to higher risks of adverse birth outcomes including preterm birth and infant low birth weight, higher risks of parental experiences of interpersonal violence, and—as our study also demonstrated—higher risks of depression symptoms.6 Depression symptoms during pregnancy can be extremely dangerous, as they precipitously increase the risk of perinatal suicide.6 While ~10% of pregnant people experience depression, as few as 20% of them can access necessary treatment.34 Similarly, in the complete case sample in our study, 698 pregnancies met EDPS criteria for postpartum depression symptoms, but only 100 reported a diagnosis (R2 = 0.22). Our findings underline the importance of screening for pregnancy intention among persons of reproductive age and screening for depression symptoms among pregnant people.

Two notable null results emerged from this research; first, we found no direct effects of restrictive abortion legislation on mental health. While traditional approaches to mediation35 required evidence of a direct effect of the intervention on the outcome in order to proceed with tests of indirect effects, recent approaches caution against such a requirement, given that mediated effects may be both statistically and clinically meaningful even when direct effects are not.36,37 The lack of a direct effect in the presence of an indirect effect can be a function of several phenomena. First, when the mediated effects and direct effects are similar in magnitude, less statistical power is necessary for detecting an indirect effect than a direct effect, particularly when mediators are more proximal to the outcome than the exposure—as is likely the case with the present study, where the policy environment is distal relative to pregnancy intention.36 Second, there may be multiple mediating pathways with equal or opposing effects; these may obscure the direct effects and make the total effect null.36 For example, for people who live in more restrictive climates, becoming pregnant may lead them to become more involved with their religious communities, to be eligible for public insurance that they could not previously access (i.e., Medicaid for pregnant women), or engage with medical (i.e., prenatal) care when they previously did not have a provider; each of these is associated with positive mental health outcomes.38–40 In the present analysis, we believe there are many mediating pathways through which restrictive abortion legislation impacts mental health during pregnancy (e.g., through the closure of health clinics that also provide mental health support), and we only tested one. Nevertheless, even in the absence of a direct effect of restrictive abortion policy on mental health outcomes, our findings of indirect effects through intention highlight the burden of these policies.

The second notable null finding is the lack of indirect effects of restrictive abortion legislation on mental health outcomes in the postpartum period. While unintended pregnancies were associated with higher risks of depression symptoms postpartum, these associations were not high enough in magnitude to mediate the effects of abortion policy climate; for postpartum depression diagnosis, we observed no relationship with either pregnancy intention or abortion policy climate. Given that a minority of people with clinically apparent postpartum depression receive appropriate medical care,34 the null findings for depression diagnosis are unsurprising. Several potential explanations arise for the discrepant results for depression symptoms in antepartum compared to postpartum period. First, the questionnaire timing (at ~5 weeks postpartum) may have been too early to sufficiently capture depression that develops later in postpartum, impacting the measure’s sensitivity to capture group differences. Second, the impact of restrictive policies may attenuate over the course of the pregnancy, leading to better mental health outcomes later in the pregnancy and during the postpartum. Finally, meaningfully different stressors at different points throughout pregnancy may make the role of intention less salient for mental health outcomes in the postpartum period compared to the antepartum period, which is consistent with our findings. For example, the psychological distress related to unintended pregnancies may be more impactful in the period of time closer to the gestational limit of abortion services (i.e., the late second trimester in many states, approximately the same time as the pregnancy questionnaire) than they are in the immediate postpartum, when the role of other stressors – i.e., financial stress, family and interpersonal stress—may play a larger role.41 Such questions will be better explored in a more racially and socioeconomically diverse sample and by examining measures of depression at different time points.

Our study adds to the growing body of literature showing the detrimental perinatal health consequences of abortion restrictions. While we focus on mental health in the perinatal period, findings from the Turnaway Study – which prospectively examined experiences of women who were denied vs. not denied a wanted abortion – demonstrated that restrictions to abortions have negative impacts on women’s health more broadly. For example, being unable to access an abortion was associated with increased exposure to intimate partner violence and increased risks of chronic pain, life-threatening birth complications, and poor self-reported physical health.42–44

Limitations

All studies of contextual exposures, including policies, are vulnerable to confounding; where people live is not randomly assigned, and uncontrolled state-level factors that influence abortion legislation may result in spurious associations between legislative environments and health outcomes. To address these biases, we not only controlled for common causes of both abortion legislation and antepartum and postpartum mental health, but we also employed a negative control approach by examining associations with a health outcome not plausibly related to abortion legislation—by observing a null association with this outcome, we are reassured that the observed main associations are unlikely to be a function of residual, uncontrolled confounding.

Questionnaire procedures limited generalizability. By the time participants received their pregnancy questionnaires (~20–25 weeks’ gestation), the majority of those who wanted and were able to obtain abortion services would have been selected out of the sample (per the post-pregnancy survey, only N=5 pregnancies from our analytic sample were reported as ending in abortion). Likely, nurses have fewer limitations accessing first-trimester abortion services than the general public. The timing of the survey could potentially lead to selection bias; that is, participants with unintended pregnancies who were able to access abortion were less likely to be captured in the analytic sample than those who were unable to access abortions. We anticipate that had we have been able to survey those participants (i.e., who had unintended pregnancies but terminated them) at the same time point as the other eligible participants, they would have been more likely to reside in less restrictive states and less likely to report depression and stress symptoms – therefore, the selection bias introduced by being unable to survey these participants likely biased our findings towards the null.

In our sample, 78% of pregnancies in were intended, which is considerably larger than the ~55% of intended pregnancies nationwide.45 Differences in health outcomes between the intended and unintended pregnancies may be systematically lower than in samples surveyed earlier in the pregnancies—making differences harder to detect and potentially biasing our results towards the null. Nevertheless, our findings are largely driven by the comparison of unintended to intended pregnancies carried to delivery, which provides useful information about the mental health consequences of restrictive abortion laws.

Misclassification may have biased associations toward the null. Pregnancy intention was measured during rather than prior to pregnancy, which could lead to misclassification of unintended pregnancies as intended.46 Further, we did not use a gold standard measure of pregnancy intention,47 and therefore, we were unable to measure all aspects of pregnancy intention with greater complexity. Additionally, symptoms of depression may have been systematically underreported due to stigma.48 However, our ability to glean associations between restrictive abortion legislation and adverse mental health during pregnancy in a sample biased towards a null finding speaks to the robustness of the observed associations.

The sample of nurses was highly homogenous in their race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. However, racial and ethnically minoritized persons not only utilize abortion services at disproportionately high rates,49 but they are also more likely to be impacted by these barriers to care because of the historic and contemporaneous ways by which structural racism, structural xenophobia, and other forms of systematic oppression restrict socioeconomic resources for people of color.50 In our analytic sample, we were unable to explore the extent to which the observed associations were more or less pronounced among racial/ethnic minorities. Similarly, our participants may have more resources to overcome the burden of abortion restrictions by, for example, traveling farther for care. Therefore, we anticipate that the associations demonstrated here underestimate the population effects of abortion legislation on mental health during and after pregnancy.

Public Health Implications

The study participants were surveyed during and after pregnancies that began between 2010–2017, when abortion was still federally legal across the U.S., yet access varied from state to state. While our study did not examine specific policies, prior research has suggested that policies targeting abortion provision51,52 – i.e., mandating clinical practices such as targeted restriction of abortion provider (TRAP) laws or FDA-approved medication abortion restrictions – are directly related to abortion provider availability, limiting the ability of people with unintended pregnancies to access timely abortion services nearby.53 Further, TRAP laws specifically have been linked to death by suicide among women of reproductive age.11 Laws that limit insurance coverage for abortion services significantly lower abortion rates, underscoring the necessity of access to not just providers but also affordable care.54–59

The impact of these laws on perinatal mental health is particularly urgent given recent dramatic changes to the U.S. policy environment. Despite overwhelming public support for federal abortion protections,60 the Supreme Court eviscerated abortion access in Dobbs v. Jackson Whole Women’s Health in June 2022. Without federal protections, variations in state-level abortion climate are critical in determining who can obtain an abortion, how, when, and under what circumstances. As of January 1, 2024, 14 states ban abortion completely.61 Our study contributes to the growing evidence base that such laws are detrimental to the health of pregnant people11,62 and their children and families,17,63 which has grave implications for future public health.

Supplementary Material

Funding support:

The Nurses’ Health Study 3 was supported by NHLBI-U01HL145386. Dr. McKetta, Dr. Charlton, Dr. Chakraborty, Dr. Soled, and Mr. Hoatson are supported by NIMHD-R01MD015256. Dr. McKetta is additionally supported by the Thomas O. Pyle Fellowship through the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation and Harvard University, NIMH T32MH013043, and the William T. Grant Foundation grant #187958. Dr. Chakraborty is additionally supported by NHLBI T32HL098048. Dr. Gimbrone is supported by NIMH T32MH013043. Dr. Beccia is supported by NIMHD F32-MD017452. Dr. Huang is supported by NCI T32CA057711. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Davis Nicole, Smoots Ashley, Goodman D Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from 14 U.S. Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008–2017. Vol 13.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health. 2019;15. doi: 10.1177/1745506519844044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingston D, Tough S. Prenatal and Postnatal Maternal Mental Health and School-Age Child Development: A Systematic Review. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(7):1728–1741. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1418-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States, 2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(19):575. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6919A2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J, Siega‐Riz AM. Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG. 2013;120(9):1116–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abajobir AA, Maravilla JC, Alati R, Najman JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herd P, Higgins J, Sicinski K, Merkurieva I. The implications of unintended pregnancies for mental health in later life. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medoff MH. State Abortion Policies, Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider Laws, and Abortion Demand. Review of Policy Research. 2010;27(5):577–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2010.00460.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medoff MH. Unintended pregnancies, restrictive abortion laws, and abortion demand. Int Sch Res Notices. 2012;2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medoff MH. The Relationship between Restrictive State Abortion Laws and Postpartum Depression. Soc Work Public Health. 2014;29(5):481–490. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2013.873997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zandberg J, Waller R, Visoki E, Barzilay R. Association Between State-Level Access to Reproductive Care and Suicide Rates Among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online December 28, 2022. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, et al. Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1573–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehler S, Rayens MK, Ashford K. Determining psychological distress during pregnancy and its association with the development of a hypertensive disorder. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;28:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Leis J, Le HN, Perry DF. A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(1–2). doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride HL, Wiens RM, McDonald MJ, Cox DW, Chan EKH. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): A Review of the Reported Validity Evidence. In: ; 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07794-9_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redd SK, Hall KS, Aswani MS, Sen B, Wingate M, Rice WS. Variation in restrictive abortion policies and adverse birth outcomes in the United States from 2005 to 2015. Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(2):103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman-Mellor SJ, Saxton KB, Catalano RC. Economic contraction and mental health: A review of the evidence, 1990–2009. Int J Ment Health. 2010;39(2):6–31. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaughlin KA, Xuan Z, Subramanian VS, Koenen KC. State-level women’s status and psychiatric disorders among US women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(11):1161–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0286-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreitzer RJ. Politics and Morality in State Abortion Policy. State Polit Policy Q. 2015;15(1):41–66. doi: 10.1177/1532440014561868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Everett BG, Agénor M. Sexual Orientation-Related Nondiscrimination Laws and Maternal Hypertension Among Black and White U.S. Women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023;32(1):118–124. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2022.0252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossick AS, Bossick NR, Callegari LS, Carey CM, Johnson H, Katon JG. Experiences of racism and postpartum depression symptoms, care-seeking, and diagnosis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2022;25(4). doi: 10.1007/s00737-022-01232-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prather C, Fuller TR, Jeffries WL, et al. Racism, African American Women, and Their Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Review of Historical and Contemporary Evidence and Implications for Health Equity. Health Equity. 2018;2(1). doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds CA, Beccia A, Charlton BM. Multiple marginalisation and unintended pregnancy among racial/ethnic and sexual minority college women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2021;35(4). doi: 10.1111/ppe.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holliday CN, McCauley HL, Silverman JG, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Women’s Experiences of Reproductive Coercion, Intimate Partner Violence, and Unintended Pregnancy. J Womens Health. 2017;26(8). doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosseel Y Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z Multiple imputation for time series data with Amelia package. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(3). doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Published online 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weisskopf MG, Tchetgen EJT, Raz R. On the use of imperfect negative control exposures in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(3). doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brooks DR, Getz KD, Brennan AT, Pollack AZ, Fox MP. The Impact of Joint Misclassification of Exposures and Outcomes on the Results of Epidemiologic Research. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5(2). doi: 10.1007/s40471-018-0147-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aiken ARA, Borrero S, Callegari LS, Dehlendorf C. Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(3):147–151. doi: 10.1363/48e10316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter E, Everett BG, Greene MZ, Haider S, Hendrick CE, Higgins JA. Pregnancy (im)possibilities: identifying factors that influence sexual minority women’s pregnancy desires. Soc Work Health Care. 2020;59(3). doi: 10.1080/00981389.2020.1737304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNamara J, Risi A, Bird AL, Townsend ML, Herbert JS. The role of pregnancy acceptability in maternal mental health and bonding during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1). doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04558-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigod SN, Wilson CA, Howard LM. Depression in pregnancy. BMJ. 2016;352. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.I1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research. Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Rourke HP, Mackinnon DP. Reasons for Testing Mediation in the Absence of an Intervention Effect: A Research Imperative in Prevention and Intervention Research. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(2):171. doi: 10.15288/JSAD.2018.79.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Rourke HP, MacKinnon DP. When the test of mediation is more powerful than the test of the total effect. Behav Res Methods. 2015;47(2):424–442. doi: 10.3758/S13428-014-0481-Z/TABLES/9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braam AW, Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality and depression in prospective studies: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;257. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrenreich K, Kimport K. Prenatal Care as a Gateway to Other Health Care: A Qualitative Study. Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(6). doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2022.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Long SK, Goin DE. Medicaid Expansions from 1997 to 2009 Increased Coverage and Improved Access and Mental Health Outcomes for Low-Income Parents. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4). doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 2006;60(3):221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts SCM, Biggs MA, Chibber KS, Gould H, Rocca CH, Foster DG. Risk of violence from the man involved in the pregnancy after receiving or being denied an abortion. BMC Med. 2014;12(1). doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0144-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerdts C, Dobkin L, Foster DG, Schwarz EB. Side Effects, Physical Health Consequences, and Mortality Associated with Abortion and Birth after an Unwanted Pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26(1). doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller S, Wherry LR, Foster DG. What Happens after an Abortion Denial? A Review of Results from the Turnaway Study. AEA Papers and Proceedings. 2020;110. doi: 10.1257/pandp.20201107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(9):843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ralph LJ, Foster DG, Rocca CH. Comparing prospective and retrospective reports of pregnancy intention in a longitudinal cohort of US women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(1):39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall J, Barrett G, Copas A, Stephenson J. London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy: guidance for its use as an outcome measure. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2017;Volume 8. doi: 10.2147/prom.s122420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gawley L, Einarson A, Bowen A. Stigma and attitudes towards antenatal depression and antidepressant use during pregnancy in healthcare students. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2011;16(5):669–679. doi: 10.1007/S10459-011-9289-0/TABLES/2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones RK, Jerman J. Population Group Abortion Rates and Lifetime Incidence of Abortion: United States, 2008–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1904–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joyce T The Supply-Side Economics of Abortion. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(16):1466–1469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Austin N, Harper S. Assessing the impact of TRAP laws on abortion and women’s health in the USA: a systematic review. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44(2):128–134. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-101866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medoff MH. The Relationship Between State Abortion Policies and Abortion Providers. Gender Issues. 2009;26(3–4):224–237. doi: 10.1007/s12147-009-9085-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medoff MH. State Abortion Policies, Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider Laws, and Abortion Demand. Review of Policy Research. 2010;27(5):577–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2010.00460.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bitler M, Zavodny M. The effect of abortion restrictions on the timing of abortions. J Health Econ. 2001;20(6):1011–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blank RM, George CC, London RA. State abortion rates the impact of policies, providers, politics, demographics, and economic environment. J Health Econ. 1996;15(5):513–553. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(96)00494-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levine PB, Trainor AB, Zimmerman DJ. The effect of Medicaid abortion funding restrictions on abortions, pregnancies and births. J Health Econ. 1996;15(5):555–578. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(96)00495-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Medoff MH. Price, Restrictions and Abortion Demand. J Fam Econ Issues. 2007;28(4):583–599. doi: 10.1007/s10834-007-9080-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henshaw SK, Joyce TJ, Dennis A, Finer LB, Blanchard K. Restrictions on Medicaid Funding for Abortions: A Literature Review.; 2009.

- 60.Saad L Americans Still Oppose Overturning Roe v. Wade. Gallup News Service. Published online 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haines J, Hubbard K, Wolf C. State Abortion Laws in the Wake of Roe v. Wade. US News and World Report. Published 2024. Accessed January 6, 2024. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/a-guide-to-abortion-laws-by-state [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu Y, Slusky DJG. The Impact of Women’s Health Clinic Closures on Preventive Care. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2016;8(3):100–124. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sen B, Wingate MS, Kirby R. The relationship between state abortion-restrictions and homicide deaths among children under 5 years of age: A longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(1):156–164. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2012.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.