Abstract

A qualitative, community-engaged assessment was conducted to identify needs and priorities for infant obesity prevention programs among mothers participating in home visiting programs. Thirty-two stakeholders (i.e., community partners, mothers, home visitors) affiliated with a home visiting program serving low-income families during the prenatal to age three period participated in group level assessment sessions or individual qualitative interviews. Results indicated families face many challenges to obesity prevention particularly in terms of healthy eating. An obesity prevention program can address these challenges by offering realistic feeding options and non-judgmental peer support, improving access to resources, and tailoring program content to individual family needs and preferences. Informational needs, family factors in healthy eating outcomes, and the importance of access and awareness of programs were also noted. To ensure the cultural- and contextual-relevance of infant obesity prevention programs for underserved populations, needs and preferences among community stakeholders and the focal population should be used as a roadmap for intervention development.

Keywords: obesity prevention, home visiting, infants, families

Introduction

Pediatric obesity (i.e., Body Mass Index [BMI] ≥ 95th percentile) is a national health epidemic affecting nearly 20% of United States youth1. Pediatric obesity is predictive of chronic and fatal health conditions throughout the lifespan, such as hypertension, coronary disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer2–4. Additionally, pediatric obesity negatively interferes with child development and is a risk factor for psychological distress5, cognitive difficulties6, decreased self-esteem7, and social stigmatization and bullying8. There are significant health disparities in obesity prevalence9,10. For example, 22.0% of Black youth and 25.8% of Latinx youth have obesity, compared to only 14.1% of White youth1. Among youth whose caregiver has a high school diploma or less, obesity rates are double compared to youth whose caregivers are college graduates (21.6% compared to 9.6%)11.

Disparities in healthy eating and feeding are already present by infancy12–15. Growth trajectories among children with severe obesity begin to deviate around 4–6 months old16, and accelerated growth starting in infancy is related to increased risk for obesity across the adult lifespan17. This increased risk is particularly concerning given the common occurrence of high BMI among infants (e.g., 9.7% of 6-month-old infants and 15.7% of 12-month-old infants display high BMI)18. Racial/ethnic minority and low-income infants display greater rates of early unhealthy eating patterns and elevated growth trajectories, suggesting health disparities in obesity risk start during infancy19,20. Early feeding and diet practices are the health behaviors that have most consistently been implicated in obesity risk in infancy, including inappropriate bottle feeding, beverage intake, protein intake, early introduction of solid foods, parental feeding practices (e.g., restrictive parenting practices), parental modeling of unhealthy eating, and limited early diet variety12–14,21. Black and Latinx children display more rapid weight gain, earlier introduction of solid foods, and higher rates of maternal restrictive feeding practices during infancy compared to their White counterparts15. Racial/ethnic minority and low-income infants also experience unique barriers and contributory factors to pediatric obesity22. Low-income children experience higher rates of food insecurity and lower access to healthy food outlets23. Low-income and Black mothers display low rates of breastfeeding initiation and continuation24–26, which is known to be a risk factor for pediatric obesity27. Racial/ethnic minority mothers are also at increased risk for elevated stress, trauma experiences, and systemic marginalization28. This constellation of risk factors contributes to the intergenerational cycle of health disparities; application of the family stress theory suggests that poverty and family stress contribute to maternal depression and parental feeding behaviors that result in increased food insecurity and pediatric obesity29.

Because infancy is a developmental period of rapid growth with lasting metabolic and behavioral consequences, infancy provides an ideal window for obesity prevention through implementation of programs that target healthy eating and feeding21,30. However, infant obesity prevention programs to date have largely been developed without considering the unique needs of underrepresented populations, which perpetuates health disparities31. There are few effective infant obesity prevention programs that are accessible and relevant for underrepresented infants32,33. For example, many obesity prevention programs are delivered in outpatient medical settings with multiple visits. These outpatient programs put underrepresented populations at a disadvantage for access and adherence due to barriers such as lack of transportation, childcare, and lack of insurance coverage31,34–36.

Incorporating infant obesity prevention into home visiting programs may be one avenue for increasing access for low-income and racial/ethnic minority families. Home visiting programs are designed to support pregnant women and parents of young children who are at risk for poor maternal and child health outcomes. Evidence-based home visiting programs serve 277, 852 families and 312, 579 children each year through over 3 million home visits37. Programs are implemented in all 50 United States and serve 54% of all United States counties37. Home visiting programs typically are funded through state and federal resources, including the federal Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program. Home visiting programs are voluntary, and families partner with home visitors to improve health, prevent maltreatment, promote education and development, and connect families to needed community resources. Home visitors typically have backgrounds in child education or development, social work, nursing, or other health and human services fields, and most home visitors have a bachelor’s degree or higher degree in their profession38. Upon joining a home visiting program, home visitors also receive extensive training within their agency and program38, including training in the specific home visiting model utilized in their program (e.g., Health Access Nurturing Development Services, Nurse Family Partnership, Healthy Families America).

Twenty-four home visiting models meet the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ criteria as evidence-based39. However, even within these evidence-based early childhood home visiting models, there is a significant gap in utilization of home visiting programs as a means of delivering obesity prevention programs, particularly for infants31. Only 17% of home visiting programs for young children address infant or child feeding cues, 11% address complementary foods, and 6% address diet variety, vegetable intake, eating dysregulation and fussiness, portion sizes, or healthy snacks40. A small number of infant obesity prevention programs delivered via home visiting currently exist and have had mixed success with improving child health. The Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Program (ECHO) targeted early obesity risk factors in infancy (e.g., diet, sleep, breastfeeding, and activity) through intervention sessions utilizing a maternal skills-based and behavioral approach involving building connections to community resources41. ECHO was delivered by home visitors already within a home visiting program network who received additional training on behavioral change strategies and intervention module content. ECHO was successful in improving breastfeeding but did not impact other dietary outcomes or infant growth41. Similarly, the Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Health Trajectories (INSIGHT) program used home visits by research nurses trained in responsive feeding interventions to target feeding, and the program effectively reduced weight gain and BMI. However, these changes in BMI were only modest and BMI percentiles did not differ between the treatment and control group30,42.

The relative ineffectiveness of many current infant obesity prevention programs may be due to a lack of culturally and contextually relevant programmatic considerations for racial/ethnic minority and low-income families. Community-engaged approaches to intervention development offer an avenue for increasing relevance for target communities. Greater stakeholder and family input is recommended for improving health and family outcomes for racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations43,44. Stakeholders may include members of the target population (e.g., families), community members and partners aware of the needs of the target population (e.g., home visitors), and community leaders in decision making roles. A community-engaged research approach offers equitable involvement of marginalized populations in research to address health disparities45–47. Stakeholders have valuable insight about the unique needs, challenges, and resources within a community, and their input can help ensure the acceptability of programs for the intended population48. Involving families from underrepresented groups in development of interventions improves the suitability of programming for meeting family needs, reduces attrition, increases recruitment, and improves patient outcomes49–52. Stakeholder engagement can also cultivate trust between academia and the community, as well as bridge the gap between science and practicality for populations most likely to utilize the intervention, which is essential for successful intervention implementation48,53–55. Given the complex barriers to healthy lifestyles among underrepresented populations56,57, development of a program to address these unique needs requires genuine engagement of the community that the program is intended to serve rather than generalizing findings from other populations or top-down academic driven approaches most frequently used in intervention development.

Despite these advantages, prior research has under-utilized community-engaged approaches to infant obesity prevention. Community perspective on how infant obesity prevention programs can meet the needs of racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations is currently unknown, and existing programs have not been developed using community-engaged approaches to ensure cultural- and contextual- relevance for families. The current study is the first to our knowledge to conduct a qualitative community-engaged assessment to identify needs and priorities for infant obesity prevention programming within home visiting from the perspective of various stakeholders (e.g., families, home visitors, community partners). This information is imperative for development of programs that are culturally and contextually relevant to address barriers to healthy eating and feeding experienced by underrepresented families at risk for health disparities.

Methods

Every Child Succeeds Home Visiting Program

Every Child Succeeds (ECS) is a regional, community-based home visiting program network within a Midwest metropolitan area. ECS utilizes three home visiting models (i.e., Health Access Nurturing Development Services, Nurse Family Partnership, and Healthy Families America) to promote positive parenting and optimize child health and development prenatally through age 3 years. Programming is delivered by home visitors with backgrounds in social work, nursing, and related professions. ECS partners with caregivers with at least one of the following characteristics that elevate risk for poor child health or developmental outcomes: unmarried, low income, <18 years of age, or receiving late or no prenatal care. All primary caregivers are eligible for the program, but the majority of caregivers enrolled are mothers (95%). Therefore, for simplicity, the term “mothers” will be used in this paper to describe program caregivers. More than half of families served (55%) have a racial/ethnic minority background. Mothers in the program also frequently have a history of trauma (69.1%58) and elevated depression (28.5%59).

ECS home visitors have backgrounds in social work, nursing, early childhood education/intervention, or a related profession. Before beginning their own caseloads, each home visitor is trained to fidelity on implementation of the home visiting model they utilize. Once home visitors satisfactorily complete all training and begin to build their own caseloads, they receive frequent and consistent supervision and coaching from their managers. During home visits, mothers learn content related to parenting skills, child development, and maternal education and mental health; mothers are also connected with community resources. While basic aspects of child nutrition are covered, the program currently does not systematically implement comprehensive and targeted obesity prevention strategies.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders associated with the ECS home visiting program were eligible to participate in the current study if they (a) were able to consent to participation (i.e., age ≥18 years old) and (b) spoke fluently in English or Spanish. Stakeholders engaged in the current study included mothers participating in the program, home visitors delivering the program, and community partners working in early child nutrition (e.g., employees of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC], a federally funded nutrition program for women and children).

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the study authors’ institutional review boards (IRBs). Families were recruited for participation through their home visitor; the research team then contacted interested families with additional study information. Stakeholders with other programmatic roles (e.g., home visitors) and community partners (e.g., WIC employees) were recruited to participate in the study via personal correspondence by the research team or program coordinator. Stakeholders completing the needs assessment were asked whether they were interested in participating in a second action planning meeting to prioritize themes identified in the needs assessment and develop steps and goals for using these themes to develop an infant obesity intervention specifically for implementation within ECS. All stakeholders endorsing interest in this meeting were contacted by research staff and invited to participate in a virtual action planning meeting.

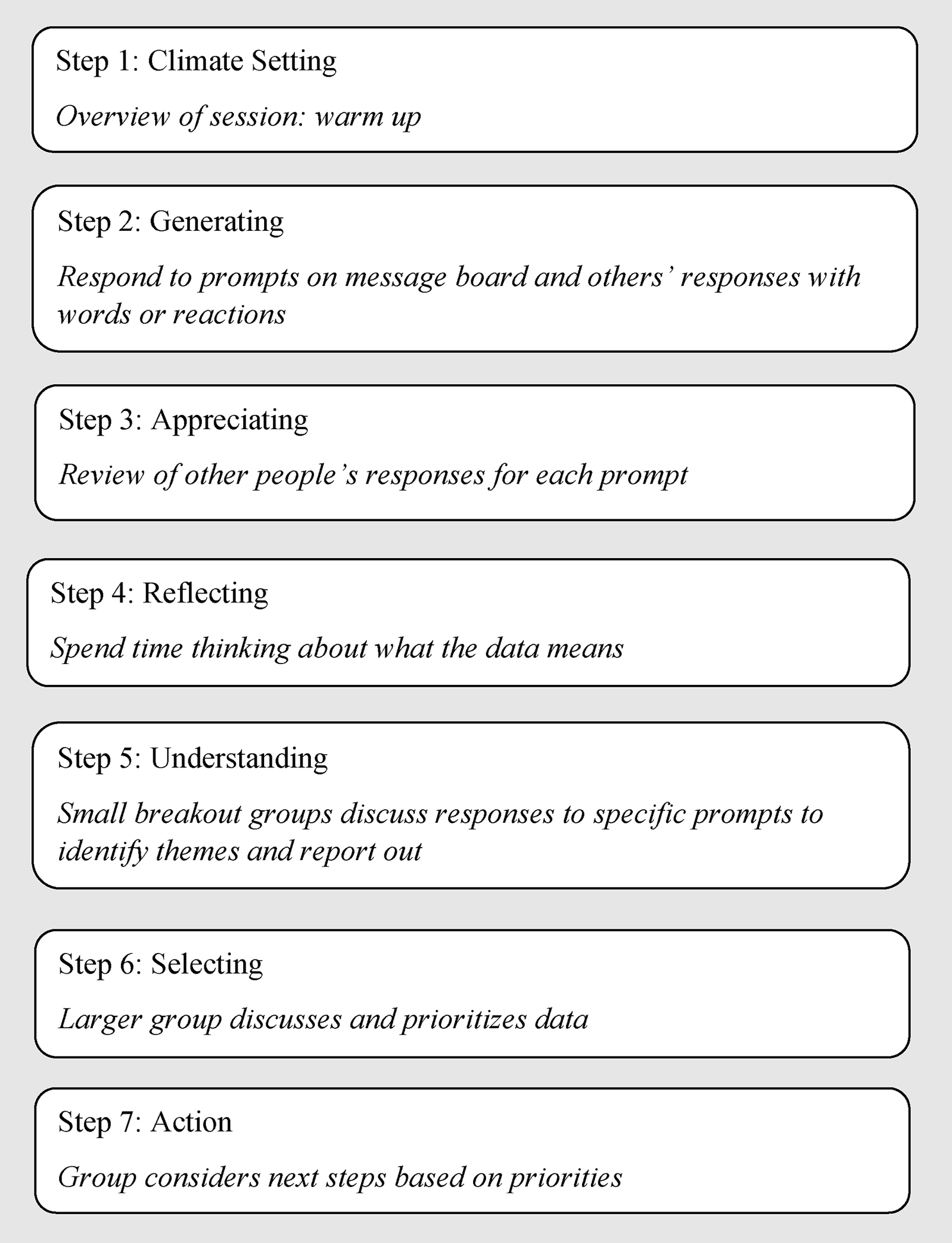

The needs assessment included participation in either a group level assessment (GLA) session offered in English and Spanish or a qualitative semi-structured interview for those who could not join a GLA session. GLA is a structured, participatory, group method, which allows for diverse groups of stakeholders from different backgrounds to engage in generating and evaluating data together to identify themes in stakeholder responses60,61. GLA generates data using a 7-step structured process guided by neutral moderators (See Figure 1). For the current study, steps 1–6 were completed all as part of one meeting, and Step 7 of creating action plans was completed through separate action planning sessions relevant to intervention development for a program specifically within the ECS home visiting program.

Figure 1: GLA Process.

GLA sessions were conducted virtually using Padlet and Zoom applications. Padlet is a cloud-based collaborative web platform that allows users to post content to virtual bulletin boards in real-time with content immediately visible to other users using the application. Bulletin boards are called “Padlets”, and a Padlet was created for each GLA session. Groups were facilitated by psychologists and psychology graduate students (COS, JR, TG, KG, AC, MN, LMV) trained by an expert in qualitative methods and GLA (LMV). Each session began with an orientation to the platforms being used and establishment of participation ground rules. Climate setting and an icebreaker activity were completed next to help build rapport and engagement among stakeholders and establish group norms of support, validation, and listening (Step 1). To generate ideas, stakeholders at each GLA session were asked to respond to a series of sentence completion prompts posted in Padlet (Step 2; See Table 1 for prompts). Prompts fell into 3 categories: aspects of getting babies to eat healthy, program aspects, trauma-informed care. Under each prompt, users posted their anonymous response, and stakeholders were able to see and respond to each other’s ideas in real time, including providing support for other ideas through a “like/heart” function (Steps 3 and 4). Step 5 involved small break out groups of stakeholders facilitated by trained research team members to examine, understand, and identify themes from the prompt responses. Groups then reported out their discussions to the larger group and any relevant overlaps among themes were discussed (Step 6).

Table 1:

GLA and Interview Prompts

| Phrasing for GLA Padlet | Phrasing for Individual Interviews |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Prompts Regarding Aspects of Getting Babies to Eat Healthy | |

|

| |

| • With families I know, it would be easier to get babies (less than 1 year) to eat healthy if we could change ……. | |

| • Life definitely gets in the way of healthy eating for babies. The thing that most gets in the way for parents in our community is…… | • Life definitely gets in the way of healthy eating for babies. What do you think most gets in the way for parents in your community? |

| • To eat healthy, babies (less than 1 year) most need…. | |

| • For parents, the easiest part of getting babies (less than 1 year) to eat healthy is…. | |

| • In terms of healthy eating for babies, parents in our community are doing well when it comes to….. | • In terms of healthy eating for babies, what are parents in our community doing well? |

| • For parents, the hardest part of getting babies (less than 1 year) to eat healthy is…. | • What is the hardest part of getting babies (less than 1 year) to eat healthy? |

| • For our community, the most important issue surrounding healthy eating for babies is…. | |

| • Families in our community want to know more about ________ when it comes to bottle feeding (breastmilk or formula) or breastfeeding. | |

| • For parents, the hardest part about bottle and breastfeeding is _________. | |

| • There is a lot of different advice in our community about _______ when it comes to giving babies table foods, bottle feeding (breastmilk or formula), or breastfeeding. | |

|

| |

| Prompts Regarding Program Aspects | |

|

| |

| • In order for parents in our community to feed their baby in a healthy way, they need to learn about _________. | |

| • To best promote healthy feeding for babies, a program for families in our community must include ….. | • What should a program include to best promote healthy feeding for babies in your community? |

| • Programs that focus on healthy feeding for babies should not waste their time talking about………. | • What aspects of healthy feeding do you think a program should not focus on? |

| • Parents in our community most want ___________ from programs on healthy feeding for babies. | |

| • Programs on healthy feeding get __________ wrong when it comes to parents in our community. | |

| • Health and social providers don’t really understand _________ about families in this community. | |

| • To better engage parents in our community in healthy feeding programs, I believe we need to …… | • In order to engage parents in our community in healthy feeding programs, what things do you think we need to do? |

| • Services/supports that parents need for healthy feeding (that aren’t available) include…. | • What services/supports are not available for healthy feeding? |

|

| |

| Prompts Regarding Trauma Informed Care | |

|

| |

| • People experience ongoing stressful things and there are many negative things that happen in our world. These things can get in the way of healthy feeding for babies when……… | |

| • Parent feelings of stress, sadness, and anger influence parenting and feeding when…………… | |

| • In order to help parents who have experienced trauma feed their babies healthy, programs need to know….. | • What can a program do to better reach families experiencing stress? |

| • People who work with families who have experienced stress and trauma could be helpful by…… | • What do you think health providers forget about in terms of stress and how it impacts life with a baby? |

Key differences between GLA and standard focus groups include the opportunity for participants to provide responses anonymously during Step 2. This dynamic may be particularly useful in contexts with an existing power differential or perceived hierarchy, such as between families and home visitors, as it encourages diverse opinions within a safely structured process60. The use of multiple methods for participation in GLA (i.e., providing written responses to prompts, using the “like/heart” function to support responses, small and large group discussion) also provides participants varied ways to voice their perspectives in the way they are most comfortable. GLA also differs significantly from focus groups in that themes are generated in real time by stakeholders during the sessions, rather than themes being coded by researchers after the session as is done in focus groups. Data are collaboratively generated and interactively analyzed among the group itself, which has participatory advantages over focus groups and other qualitative methods60,61.

To capture unique cultural input, we conducted three GLA sessions divided by race and ethnicity (i.e., White, Black, Latinx). The session for Latinx families was conducted in Spanish. Based on input from program home visitors and staff regarding methods that would best facilitate participation by Latinx mothers, GLA procedures were modified for the GLA conducted in Spanish. Rather than using a written Padlet, the facilitator of breakout groups read each prompt aloud to facilitate conversation. To help document the process, Spanish-speaking home visitors assisted the facilitators by writing responses in Padlet. After each group worked through discussing their prompts, the facilitators read back the written responses in Padlet, and stakeholders identified themes in the responses. In the discussion, the facilitators did not offer any of their own insights, opinions, or suggestions; rather, the facilitators worked to encourage conversation among the stakeholders. Due to raised concerns regarding family comfort level with reporting out to the larger group that were noted by home visitors for Latinx families, all analysis of themes for the Latinx group were conducted in small groups.

We experienced limited attendance at our attempts to do a GLA session with Black mothers. Specifically, our first scheduled GLA session was not attended by any Black mothers, and our rescheduled GLA session only was attended by 1 Black mother, despite a number of Black mothers registering to attend. Therefore, our team sought to use an alternative method for obtaining the perspective of Black mothers, specifically semi-structured qualitative interviews. Black mothers who had registered to attend a GLA session were invited to instead complete a semi-structured qualitative interview. All mothers approached to complete an interview chose to do so. Because this option was added retroactively after Latinx and White mothers had already completed the GLA methodology, individual interviews were not offered to these other participants. Interviews were conducted by a psychology graduate student who guided conversation through use of a selection of the same prompts used in the GLA sessions. To not over-burden mothers with a lengthy interview, a selection of prompts from each of the three categories (i.e., getting babies to eat healthy, program aspects, trauma informed care) were used for the interview (see Table 1). Prompts were adapted to open-ended questions for the one-on-one interviews, and questions regarding trauma-informed care were modified to be more sensitive for one-to-one interviews. During interviews, probes to further participant dialogue included: “Which one of those do you think is the most important?”, “Tell me more about that…”, “Tell me about why that is important.”, “What do you mean by that?”. Interviews lasted on average 27.2 minutes (range 17.8 minutes- 35.5 minutes). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

A subset of interested stakeholders (n = 8) attended a subsequent meeting focused on action planning specific to the needs of the ECS home visiting program. At this meeting, stakeholders completed a survey to rate the importance of each identified theme on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., 1 = not important to 5 = extremely important). Each theme was presented along with a brief description of the theme, and stakeholders were given the following instructions: “Below are ideas that stakeholders came up with as important things to include in a healthy eating program for babies 3–9 months old in the ECS home visiting program. We want to know how much you would want these things to be part of this healthy eating program and how much you think a program could actually do these things.” Importance ratings were used to prioritize objectives of the healthy eating program being designed for the ECS home visiting program.

Data Analysis

Analysis of GLA themes occurred in real-time within the needs assessment meetings. Stakeholder responses to the Padlet prompts were discussed within small groups during the meeting (outlined above), and stakeholders identified together as a group the themes in their responses. This approach has advantages over other qualitative approaches because it limits the insertion of researcher bias into themes generation61. Because GLA is designed for collaborative theme development during the sessions, we did not collect individual-level data regarding statements contributing to themes, as is done in focus groups (e.g., number of participants endorsing each theme).

For individual interviews, three research team coders reviewed transcripts to examine whether any new ideas were presented beyond the themes already developed from the previous GLA sessions. New content that did not fall under the previously established themes was managed through either (a) modifying existing themes from the GLA sessions to include new content or (b) creation of new themes. The three researchers coding interview transcripts discussed to consensus whether modifying existing themes or creating new themes was most appropriate to incorporate perspectives from interviews.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze importance ratings from the action planning session.

Results

Stakeholders

Twenty-four stakeholders completed a GLA session, and eight stakeholders completed individual phone interviews. All stakeholders self-identified as female and were diverse in terms of race and ethnicity (40.6% White, 34.4% Black, 21.9% Latinx, 3.1% Mixed Race). The majority of stakeholders were mothers of a child in the home visiting program (n = 21, 65.6%). See Table 2 for complete participant demographics. Eight stakeholders participated in the action planning phase and completed ratings of the importance of identified themes; these stakeholders were all female (100.0%) and primarily White (87.5%).

Table 2:

Stakeholder Demographics

| Needs Assessment Participants n (%) | Action Planning Participants n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 32 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| White | 13 (40.6%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Black | 11 (34.4%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Latinx | 7 (21.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mixed Race | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

|

| ||

| Role in Home Visiting Program | ||

| Mother | 21 (65.6%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Home Visitor | 8 (25.0%) | 4 (50.0%) |

| WIC employee | 2 (6.3%) | 2 (25.0%) |

| Board Member | 1 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Themes

Ten themes emerged through the needs assessment. The research team synthesized and integrated themes and identified four overarching meta-themes. The average importance ratings of identified themes ranged from 3.6 to 5.0, on a scale from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important). See Table 3 for a detailed description of each theme and importance ratings. Themes rated as most important included that “Families need feeding options that are realistic and fit with their life,” “Caregivers need all types of support that is not judgmental (e.g., emotional, social),” and “Nutrition information is complex”.

Table 3:

Meta-Themes and Identified Needs

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Meta-Theme: Recognize the individual and provide support | |

|

Families need feeding options that are realistic and fit within their life. Description: Programs should provide families with health goals and recommendations that are perceived by families as feasible, obtainable, and accessible. The recommendations given in current programs are not possible sometimes and just talking about the recommendations does not give families much information on what they can actually do. Families have busy schedules and a lot of demands that get in the way of feeding, and these things need to be considered when thinking about options. |

5.00 (.00) |

|

Caregivers need all types of support that is not judgmental (emotional, social). This means from program staff or healthcare providers who often do not seem engaged or like they do not have time for families. Families also want to have support from families and mothers like them which might come from the community or from family groups. Description: Programs should seek to be supportive, nonjudgmental, trustworthy, and to truly understand and hear the experiences of families. This includes positive praise to incentivize people to keep working on healthy eating. This support could be emotional, social, financial, or resources. Stakeholders also noted that these supports should be frequent with frequent check-ins. Because families each have strengths, they can offer support to each other. |

4.63 (.74) |

|

Improving access to healthy foods, things needed for healthy eating (e.g., highchairs, food coupons), and other resources beyond just those for feeding (e.g., transportation, diapers, finances, social determinants of health). Description: Families experience challenges and barriers to accessing healthy food, such as cost, food waste, finding food, transportation to access food, and convenient options for healthy food since many convenient options do not offer healthy foods. Programs could include strategies such as how to budget, coupon, linking to food pantries, how to store fresh produce to preserve longer, etc. |

4.38 (1.06) |

|

Individual families and babies are different, and programs need to meet them where they are. All families already have things that are going well, strengths, and assets. Programs need to recognize what is going well for families and build on their strengths. Description: Families have different needs and are interested in different information, and therefore, tailoring programs and information to individual families is needed. The program may need to look different for each family (e.g., some infants are fussier and feeding them is harder, every family has different family members involved in feeding). Every family wants to receive different information in different ways and the information that is relevant varies for families. Infants have different personalities and cues and families recognized this makes feeding more difficult for some infants and changes how they need to respond. |

3.88 (1.13) |

| Meta-Theme: Need for clear and individualized information | |

|

Nutrition information is complex. This means that people hear different messages in different places and different pieces of nutrition information are relevant or desired by each family. Information needs to be clear, understandable, and include specific action things to do (e.g., recipes) when possible. Information also needs to be accessible to families (e.g., putting in the format easiest for them to access).

Description: Families receive a lot of inaccurate, conflicting, and confusing information. Assisting families with differentiating facts from opinions, myths, or old information is valuable. Programs need to provide quick, accurate, consistent, and understandable education to families. Step-by-step instructions and information are helpful. |

4.50 (.53) |

|

Families want specific pieces of information about nutrition and mealtime behaviors, but the information wanted is different for each family.

Description: Families benefit from information specific to their actual questions and that does not repeat knowledge they already have. The specific information desired is different for each family, and it is not one size fits all. Some families want information that is exactly what other families do not want. Stakeholders expressed a need for knowledge on specific nutrition or mealtime topics, such as knowledge about what is healthy eating, consequences of unhealthy eating, reading nutrition labels and understanding what good nutrition is, healthy eating habits, modeling healthy eating, etc. |

3.63 (.74) |

| Meta-Theme: Influence of caregiver factors and feeding beliefs | |

|

Caregiver factors influence child feeding. Caregiver mental health and wellbeing, stress, and self-care are important in infant feeding and parenting. Caregivers modeling healthy behaviors is also important for kids being healthy.

Description: Mental health and stress influence the ability for healthy eating, and therefore mental health support should be more accessible and incorporated into healthy eating programs. This mental health support needs to be individualized and not assume that everyone has clinical mental health problems. All families have self-care and wellbeing things going well, and all families have unique needs of where to focus. |

3.88 (1.13) |

|

Breastfeeding is something that families have many feelings and needs around.

Description: Stakeholders expressed that families have many mixed feelings, thoughts, and experiences about breastfeeding. There is a need to support breastfeeding but also understand when caregivers cannot breastfeed and when there are barriers to breastfeeding. When breastfeeding is not possible, caregivers can benefit from information on what are best alternative options. |

3.63 (.92) |

| Meta-Theme: Access and awareness of healthy eating programs | |

|

Families recognize it is better to get infants started eating healthy early.

Description: It is hard to get kids to change behaviors once they are already used to tastes and textures of unhealthy foods, and therefore, it is better to get them started eating healthy from the very beginning. It is important to increase food variety early and to address this early. Families already recognize this importance and are ready to work on it. |

4.25 (.89) |

|

A program needs to be accessible and well-advertised, so families know about it and why it is important. Description: Families need to be made aware of healthy eating programs, and it needs to be clear why the program is important. Sometimes, families do not receive information on all the resources available for healthy feeding. For this reason, there needs to be more widely shared information about local resources on social media. |

4.25 (.46) |

Recognize the individual and provide support.

During the GLA, stakeholders talked about the many challenges that families face to healthy eating and how challenges and strengths vary for each family. Stakeholders discussed that programs should provide families realistic and practical healthy eating goals that fit with the lives of families. A need for assisting families with accessing resources, including services outside of feeding (e.g., transportation, finances) was also noted. Further, stakeholders emphasized how families need support from others, including non-judgmental support and support from other families with similar backgrounds and lived experience. They shared that this support would need to be distinct from their experiences with healthcare providers who they reported lacked time to engage with families. It was also noted that individual infants and their families experience unique challenges related to healthy eating and also have individual strengths and areas that are already going well.

Need for clear and individualized information.

Stakeholders also noted in multiple themes the idea that families need different types of information (including about different aspects of nutrition and mealtimes) and distinct goals and recommendations. Related to information, stakeholders also identified the challenges of hearing and interpreting conflicting information regarding nutrition and feeding.

Influence of caregiver factors and feeding beliefs.

Stakeholders described that caregiver mental health, wellbeing, stress, and self-care are important factors that influence infant feeding and parenting. The influence of caregiver modeling of health behaviors was also noted. In terms of caregiver behaviors, stakeholders noted that families experience many different thoughts, beliefs, and feelings around breastfeeding and whether they are successful or not with breastfeeding.

Access and awareness of healthy eating programs.

Stakeholders noted that a healthy eating program should be accessible and well-advertised so that families know about it and why it is important. Stakeholders also recognized the importance of early intervention and having children establish healthy eating habits early.

Discussion

The current study utilized a community-engaged approach to evaluate the needs of low-income and racial/ethnic minority families enrolled in a home visiting program to inform the development of infant obesity prevention programs. Our findings add novelty to the body of knowledge in this field and suggest that healthy infant eating and obesity prevention programs for low-income and racial/ethnic minority families participating in a home visiting program should include both nutritional information and family support. Specifically, stakeholders described the need to recognize individual family needs, challenges, and strengths, provide support (both social and resource support), consider caregiver factors, and increase access and awareness of the program.

Stakeholders in the current needs assessment highlighted the number of challenges that families experience for healthy infant feeding and how these challenges, as well as strengths, vary across families. It was noted as important for providers to present realistic options that fit within families’ lives and the challenges to healthy eating. Access to food and other resources was noted as one challenge that some families may experience to healthy eating. Stakeholders emphasized the need to increase general access to healthy food (e.g., finding stores that carry nutritious foods, cost of healthy foods) and tips and strategies related to budget-friendly healthy eating (e.g., budgeting, coupons, preserving produce). Similar accessibility barriers to healthy foods have been well-documented in prior literature, particularly among low-income and/or racial/ethnic minority adults62,63. Ensuring obesity prevention programs provide and connect families to resources to address these accessibility barriers (e.g., financial barriers) is critical for effective intervention. Obesity prevention programs could also help families plan their meals prior to going to the store to reduce food waste and cost, provide recipes with step-by-step instructions and simple ingredients that families are already familiar with, and offer realistic options that fit within the family’s needs and lifestyle. For example, if families do not have the time or resources to cook dinner at home, recommendations could include healthy items to get at fast-food restaurants or convenience stores.

Stakeholders noted the need for assistance in accessing services beyond feeding (e.g., transportation, diapers). A similar finding was reported when assessing barriers to using health services in a study among ethnic minority adults, such that lack of finances, non-reliable transportation, prolonged travel time, and an unawareness of service availability were reported as barriers to using health care services64. To help families practice healthy infant feeding and eating, it is critical for the family’s most pressing needs to be addressed first. For example, it is unrealistic to ask a family to focus on buying fruits and vegetables to increase exposure for their infant when they are struggling to afford diapers or formula. Home visiting may also be an avenue for overcoming some of these barriers low income and racial/ethnic minority families experience (e.g., eliminating need for transportation to access services, informing families of resources available, connecting families directly with resources)31. Although systemic factors may not be able to be combatted as part of intervention implementation, assessment can allow for tailoring of content to fit each family and target the most pressing needs of families participating in these types of interventions. It is important for intervention development with low-income and racial/ethnic minority families to consider resources needed outside of the scope of the intervention to help combat potential barriers for family participation or retention.

The need for clear and individualized information related to nutrition and healthy eating was articulated. All families and babies are different and may require individualized information presented as part of an intervention (e.g., about different aspects of nutrition and mealtimes), distinct goals, and recommendations. These findings are consistent with previous literature in other pediatric obesity interventions that demonstrated positive health-related benefits of individualized approaches65,66. Further, it is important for these interventions to provide consistent nutritional information and remain up to date with recommendations when providing information to families; stakeholders in the needs assessment noted that families often hear conflicting information regarding nutrition and feeding. With feeding and nutrition guidelines constantly evolving and not always being consistent across providers and healthcare organizations, it may be difficult for families to determine which guidelines to follow, representing a systems-level barrier to healthy feeding and eating. Further, the abundance of information families receive from the internet, social media, and family and friends may increase confusion and lead to suboptimal feeding and eating behaviors. Thus, development of interventions could utilize strategies to discuss and dispel myths with families, particularly around infant feeding and nutrition, rather than engaging in one-sided educational interventions. Allowing for greater back-and-forth conversation with families may also help interventions target specific areas, increasing buy-in for families to make healthy behavioral changes67,68.

Stakeholders recognized the importance of caregiver factors and their influence on infant health outcomes, including the role of caregiver mental health and stress management. Maternal stress has been linked to infant feeding behaviors (e.g., non-responsive feeding, reduced duration of breastfeeding)69,70. Support around maternal mental health is particularly important in the current sample, considering postpartum is a period of increased maternal stress71, and low-income and racial/ethnic minority mothers are at risk for greater parenting stress and mental health symptoms58,72–74. It is noteworthy that stakeholders consistently emphasized the need for support to be trustworthy, non-judgmental, and come from families with similar backgrounds. This feedback underscores the importance of community-engagement in pediatric obesity prevention programs75. Although community members could not provide mental health assessment or psychotherapy to families, they could practice active listening to better understand the families’ experiences and sources of stress, share stress management strategies, highlight the families’ strengths, and provide mental health referrals when necessary.

Notably, many of the themes generated by stakeholders, such as the needs for non-judgmental support, access to resources, and individually tailored information, are not specific exclusively to healthy eating interventions or to intervention efforts during infancy. Despite our use of prompts specifically referencing healthy eating and infancy, stakeholders generated themes with broader scope and relevance. This finding speaks to the shared barriers and needs of families who face health inequities, and barriers to healthy eating during infancy may be those same factors impacting other areas of health and other age groups. Rather than experiencing unique barriers to healthy eating during infancy, families experienced larger needs that may underly risk for health disparities more generally. Therefore, our study results may have implications for programs working with low-income and racial/ethnic minority populations more broadly, beyond simply infant obesity prevention programs. Relatedly, this broad nature of themes suggests potential generalizability of our results beyond just the ECS home visiting program.

Limitations

The current study has several strengths including having a racially and ethnically diverse sample and obtaining perspectives from key stakeholders. However, there are limitations that should be considered when interpreting study findings. First, the overall sample was small; having a larger sample may have generated different themes. Although qualitative methods were necessary to accomplish the study’s objective (i.e., to understand the needs, resources, and barriers to healthy infant eating and feeding), additional data regarding infant eating behaviors, parent feeding practices, or trauma history may have strengthened study conclusions. GLA requires public sharing of perspectives, and therefore, stakeholder comfort with discussing topics in public (including in a situation where there may be power differential among stakeholders, such as mothers and home visitors) may influence contributions and more sensitive issues may not be represented. However, GLA facilitators are trained in encouraging a participatory atmosphere that promotes equity in contribution across stakeholders. Further, real-time analysis of themes in GLA is based on consensus among the group, which may lead to nuances or outlier data not being represented in resulting themes. Our need to use two different qualitative methodologies (i.e., GLA, individual interviews) is also a potential limitation as there were methodological differences to these approaches that may have altered participant responses, such as differences in the number of prompts used and the different dynamic of individual interviews versus group assessments.

As with any research study, stakeholders enrolled in the current study may not represent all members involved in the home visiting program. It is possible that some individuals wanted to participate but did not have the time or resources (e.g., internet, time off work) to enroll in the study, and their barriers may have differed from those who were interested and could attend. It is also important to note that participants in the action planning meeting rating the importance of each theme were predominantly home visitors and White. Black and Latinx stakeholders were underrepresented in the action planning meeting, and the perceived importance of each theme is likely to be different based on one’s cultural background or role in the home visiting program. Lastly, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, GLA sessions and interviews were conducted virtually either through Zoom or phone. Some stakeholders may have felt uncomfortable sharing their thoughts in a virtual format, experienced technical issues that went unknown to needs assessment facilitators, or were unfamiliar with the virtual platform, which may have hindered optimal engagement in the needs assessment. However, it is important to note that research staff were available to families prior to meetings to assist with Zoom set-up and familiarity, and no technical challenges were noted during sessions.

Conclusion

Our qualitative needs assessment with key stakeholders from a home visiting program identified 4 meta-themes considered to be critical components for an effective home visiting-based infant healthy eating program for low-income and racial/ethnic minority families. Specifically, stakeholders identified the need for individualized and realistic healthy eating and feeding options, accurate information about current nutritional guidelines, assistance with overcoming barriers and finding resources, and non-judgmental support across areas (e.g., social, emotional, financial). This information can be used to develop culturally and contextually relevant pediatric obesity prevention programs. Future research should focus on mixed methods study designs with larger sample sizes to expand upon the current study’s findings.

References

- 1.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer BP, Nelson JA, Holub SC. Childhood Body Mass Index trajectories predicting cardiovascular risk in adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(6):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tirosh A, Shai I, Afek A, et al. Adolescent BMI trajectory and risk of diabetes versus coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1315–1325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umano GR, Pistone C, Tondina E, et al. Pediatric obesity and the immune system. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:487. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalra G, De Sousa A, Sonavane S, et al. Psychological issues in pediatric obesity. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.110941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Dai Q, Jackson JC, et al. Overweight is associated with decreased cognitive functioning among school-age children and adolescents. Obesity. 2008;16(8):1809–1815. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang NR, Kwack YS. An update on mental health problems and cognitive behavioral therapy in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23(1):15. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2020.23.1.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieb DC, Snow RE, DeBoer MD. Socioeconomic factors in the development of childhood obesity and diabetes. Clin Sports Med. 2009;28(3):349–378. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watts AW, Mason SM, Loth K, et al. Socioeconomic differences in overweight and weight-related behaviors across adolescence and young adulthood: 10-year longitudinal findings from Project EAT. Prev Med. 2016;87:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, et al. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013–2016. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aris IM, Bernard JY, Chen LW, et al. Modifiable risk factors in the first 1000 days for subsequent risk of childhood overweight in an Asian cohort: Significance of parental overweight status. Int J Obes. 2018;42(1):44–51. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dattilo AM. Programming long-term health: Effect of parent feeding approaches on long-term diet and eating patterns. In: Early Nutrition and Long-Term Health. Elsevier; 2017:471–497. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-100168-4.00018-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietrobelli A, Agosti M, the MeNu Group. Nutrition in the first 1000 Days: Ten practices to minimize obesity emerging from published science. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1491. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smego A, Woo JG, Klein J, et al. High Body Mass Index in infancy may predict severe obesity in early childhood. J Pediatr. 2017;183:87–93.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson J, Forsén T, Osmond C, et al. Obesity from cradle to grave. Int J Obes. 2003;27(6):722–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown CL, Skinner AC, Steiner MJ, et al. Prevalence of high weight status in children under 2 Years in NHANES and statewide electronic health records data in North Carolina and South Carolina. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(8):1353–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fein SB, Labiner-Wolfe J, Scanlon KS, et al. Selected complementary feeding practices and their association with maternal education. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Supplement_2):S91–S97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman DS, Sharma AJ, Hamner HC, et al. Trends in weight-for-length among infants in WIC from 2000 to 2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20162034. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, et al. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(6):761–779. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumanyika SK, Grier S. Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. Future Child. 2006;16(1):187–207. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tester JM, Rosas LG, Leung CW. Food insecurity and pediatric obesity: A double whammy in the era of COVID-19. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(4):442–450. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00413-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beauregard JL, Hamner HC, Chen J, et al. Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(34):745–748. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heck KE, Braveman P, Cubbin C, et al. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(1):51–59. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedberg IC. Barriers to breastfeeding in the WIC population. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2013;38(4):244–249. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182836ca2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiao J, Dai LJ, Zhang Q, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between breastfeeding and early childhood obesity. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;53:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conradt E, Carter SE, Crowell SE. Biological embedding of chronic stress across two generations within marginalized communities. Child Dev Perspect. 2020;14(4):208–214. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCurdy K, Gorman KS, Metallinos-Katsaras E. From poverty to food insecurity and child overweight: A family stress approach. Child Dev Perspect. 2010;4(2):144–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00133.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman SL, et al. Preventing obesity during infancy: A pilot study. Obesity. 2011;19(2):353–361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salvy SJ, de la Haye K, Galama T, et al. Home visitation programs: An untapped opportunity for the delivery of early childhood obesity prevention. Obes Rev. 2017;18(2):149–163. doi: 10.1111/obr.12482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blake-Lamb TL, Locks LM, Perkins ME, et al. Interventions for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 Days: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(6):780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall S, Taki S, Laird Y, et al. Cultural adaptations of obesity-related behavioral prevention interventions in early childhood: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;23(4). doi: 10.1111/obr.13402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irby MB, Boles KA, Jordan C, et al. TeleFIT: Adapting a multidisciplinary, tertiary-care pediatric obesity clinic to rural populations. Telemed E-Health. 2012;18(3):247–249. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: A review of the literature and new directions: Attrition in paediatric weight management. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e273–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeller M, Kirk S, Claytor R, et al. Predictors of attrition from a pediatric weight management program. J Pediatr. 2004;144(4):466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Home Visiting Resource Center (2022). Home Visiting Yearbook. Published online 2022. Accessed March 10, 2023. 2023 from: https://nhvrc.org/yearbook/2022-yearbook/

- 38.Sandstorm H, Benatar S, Peters R, et al. Home Visiting Career Trajectories: Final Report. OPRE Report. Urban Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Early Childhood Home Visiting Models: Reviewing Evidence of Effectiveness. Homvee; 2022. https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11/homvee_summary_brief_nov2022.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welker EB, Lott MM, Sundermann JL, et al. Integrating healthy eating into evidence-based home visiting models: An analysis of programs and opportunities for dietetic practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(9):1423–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.08.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cloutier MM, Wiley JF, Kuo CL, et al. Outcomes of an early childhood obesity prevention program in a low-income community: A pilot, randomized trial. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(11):677–685. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, et al. Effect of a responsive parenting educational intervention on childhood weight outcomes at 3 years of age: The INSIGHT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(5):461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byrne M. Increasing the impact of behavior change intervention research: Is there a role for stakeholder engagement? Health Psychol. 2019;38(4):290–296. doi: 10.1037/hea0000723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrington DM, Brady EM, Weihrauch-Bluher S, et al. Development of an interactive lifestyle programme for adolescents at risk of developing type 2 diabetes: PRE-STARt. Children. 2021;8(2):69. doi: 10.3390/children8020069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balls-Berry JE, Acosta-Pérez E. The use of community engaged research principles to improve health: Community academic partnerships for research. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36(2):84–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol. 2018;73(7):884–898. doi: 10.1037/amp0000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wallerstein N. Engage for equity: Advancing the fields of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research in community psychology and the social sciences. Am J Community Psychol. 2021;67(3–4):251–255. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brockman TA, Sim LA, Biggs BK, et al. Healthy eating in a Boys & Girls Club afterschool programme: Barriers, facilitators and opportunities. Health Educ J. 2020;79(8):914–931. doi: 10.1177/0017896920936722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brito FA, Zoellner JM, Hill J, et al. From Bright Bodies to i Choose: Using a CBPR approach to develop childhood obesity intervention materials for rural Virginia. SAGE Open. 2019;9(1):215824401983731. doi: 10.1177/2158244019837313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cruz TH, Davis SM, FitzGerald CA, et al. Engagement, recruitment, and retention in a trans-community, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in rural American Indian and Hispanic children. J Prim Prev. 2014;35(3):135–149. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0340-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tapp H, White L, Steuerwald M, et al. Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(4):405–419. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unertl KM, Schaefbauer CL, Campbell TR, et al. Integrating community-based participatory research and informatics approaches to improve the engagement and health of underserved populations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):60–73. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Araújo-Soares V, Hankonen N, Presseau J, et al. Developing behavior change interventions for self-management in chronic illness: An integrative overview. Eur Psychol. 2019;24(1):7–25. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berge JM, Everts JC. Family-based interventions targeting childhood obesity: A meta-Analysis. Child Obes. 2011;7(2):110–121. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.07.02.1004.berge [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004;(99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, et al. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: Implications for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2211–2221. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fulgoni V, Drewnowski A. An economic gap between the recommended healthy food patterns and existing diets of minority groups in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–14. Front Nutr. 2019;6:37. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Folger AT, Putnam KT, Putnam FW, et al. Maternal interpersonal trauma and child social-emotional development: An intergenerational effect. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2017;31(2):99–107. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevens J, Ammerman RT, Putnam FG, et al. Depression and trauma history in first-time mothers receiving home visitation. J Community Psychol. 2002;30(5):551–564. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaughn LM, DeJonckheere M. Methodological Progress Note: Group Level Assessment. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10). doi: 10.12788/jhm.3289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaughn LM, Lohmueller M. Calling all stakeholders: Group-Level Assessment (GLA)—A qualitative and participatory method for large groups. Eval Rev. 2014;38(4):336–355. doi: 10.1177/0193841X14544903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freedman DA, Blake CE, Liese AD. Developing a multicomponent model of nutritious food access and related implications for community and policy practice. J Community Pract. 2013;21(4):379–409. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2013.842197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiig K, Smith C. The art of grocery shopping on a food stamp budget: Factors influencing the food choices of low-income women as they try to make ends meet. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(10):1726–1734. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheppers E, Van Dongen E, Dekker J, et al. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: A review. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):325–348. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chai LK, Collins C, May C, et al. Effectiveness of family-based weight management interventions for children with overweight and obesity: An umbrella review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(7):1341–1427. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoelscher DM, Brann LS, O’Brien S, et al. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity: Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics based on an umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(2):410–423.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2021.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.August GJ, Gewirtz A, Realmuto GM. Moving the field of prevention from science to service: Integrating evidence-based preventive interventions into community practice through adapted and adaptive models. Appl Prev Psychol. 2010;14(1–4):72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.appsy.2008.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaughn LM, Whetstone C, Boards A, et al. Partnering with insiders: A review of peer models across community-engaged research, education and social care. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(6):769–786. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Black MM, Aboud FE. Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. J Nutr. 2011;141(3):490–494. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.129973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DiGirolamo A, Thompson N, Martorell R, et al. Intention or experience? Predictors of continued breastfeeding. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(2):208–226. doi: 10.1177/1090198104271971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matvienko-Sikar K, Cooney J, Flannery C, et al. Maternal stress in the first 1000 days and risk of childhood obesity: A systematic review. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2021;39(2):180–204. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2020.1724917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bloom T, Glass N, Curry MA, et al. Maternal stress exposures, reactions, and priorities for stress reduction among low-income, urban women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(2):167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00197.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herba CM, Glover V, Ramchandani PG, et al. Maternal depression and mental health in early childhood: An examination of underlying mechanisms in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):983–992. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nam Y, Wikoff N, Sherraden M. Racial and ethnic differences in parenting stress: Evidence from a statewide sample of new mothers. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(2):278–288. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9833-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Po’e EK, Gesell SB, Caples LT, et al. Pediatric obesity community programs: Barriers & facilitators toward sustainability. J Community Health. 2010;35(4):348–354. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9262-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]