Abstract

Cancer cell fate has been widely ascribed to mutational changes within protein-coding genes associated with tumor suppressors and oncogenes. In contrast, the mechanisms through which the biophysical properties of membrane lipids influence cancer cell survival, dedifferentiation and metastasis have received little scrutiny. Here, we report that cancer cells endowed with a high metastatic ability and cancer stem cell-like traits employ ether lipids to maintain low membrane tension and high membrane fluidity. Using genetic approaches and lipid reconstitution assays, we show that these ether lipid-regulated biophysical properties permit non-clathrin-mediated iron endocytosis via CD44, leading directly to significant increases in intracellular redox-active iron and enhanced ferroptosis susceptibility. Using a combination of in vitro three-dimensional microvascular network systems and in vivo animal models, we show that loss of ether lipids also strongly attenuates extravasation, metastatic burden and cancer stemness. These findings illuminate a mechanism whereby ether lipids in carcinoma cells serve as key regulators of malignant progression while conferring a unique vulnerability that can be exploited for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Ether lipids, membrane tension, endocytosis, CD44, iron, metastasis, ferroptosis

INTRODUCTION

Cancer cells have the capacity to undergo dynamic changes in identity, structure, and function, making them remarkably versatile and adaptable. Alterations in the lipid composition of cell membranes is one key element contributing to the phenotypic plasticity of cells. The distinctive physicochemical properties and subcellular localization of various lipids within cell membranes influence a range of biological processes, including cellular trafficking, signaling and metabolism1. Despite our growing knowledge of lipid biology, our understanding of how specific lipid subtypes impact cancer cell fate remains limited.

Emerging studies have demonstrated that therapy-resistant mesenchymal-like carcinoma cells exhibit an elevated vulnerability to ferroptosis2–4, an iron-dependent form of cell death characterized by the unrestricted accumulation of oxidized membrane phospholipids5–7. Indeed, in previous work we showed that the natural product salinomycin can selectively eliminate otherwise therapy resistant, mesenchymal-enriched cancer stem cells (CSC), doing so by targeting lysosomal iron to promote an iron-dependent cell death4, 8, 9. In this context, we found that such CSC-enriched cells exhibit a high intracellular iron load compared to their non-CSC-like counterparts, rendering them especially vulnerable to elimination by induced ferroptosis13,14.

Ferroptosis can also be instigated by pharmacologic inhibition of ferroptosis suppressors, such as glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)5, 10, ferroptosis-suppressor protein 1 (FSP1, previously known as AIFM2)11, 12, as well as through downregulation of reduced glutathione (GSH)13, 14. Activated CD8+ T cells may also induce ferroptosis in cancer cells9,10. Beyond cancer, ferroptosis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases and acute injury of the kidney, liver and heart15–18.

In previous work, we undertook an unbiased, genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen with the goal of identifying genes that govern ferroptosis susceptibility in high-grade human serous ovarian cancer cells19. This screen revealed a previously unrecognized role for ether lipid-synthesizing enzymes, such as alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS), in modulating ferroptosis susceptibility. The ether phospholipids generated by these enzymes represent a unique subclass of glycerophospholipids characterized by an ether-linked hydrocarbon group formed at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone20. This phospholipid subtype constitutes ~20% of the total phospholipid pool in many types of mammalian cells.

The significance of ether lipid species in human health is underscored by the severe inherited peroxisomal disorders caused by their deficiency20. This often manifests as profound developmental abnormalities, such as neurological defects, visual and hearing loss, and reduced lifespan. In the context of cancer, elevated ether lipid levels have been correlated with increased metastatic potential of carcinoma cells21–24. Despite these pathological associations, the mechanism(s) by which ether lipids affect cancer progression remain(s) elusive. Furthermore, exactly why loss of ether lipids results in decreased ferroptosis susceptibility required further investigation.

Our previous work and that of others ascribed a role to polyunsaturated ether phospholipids as chemical substrates prone to the iron-mediated oxidation that triggers ferroptotic cell death19, 25. Here, we demonstrate that ether lipids also play an unrelated biophysical role, doing so by facilitating iron endocytosis in carcinoma cells. This represents an unappreciated mechanism of intracellular signaling in which a lipid contributes to the intracellular level of a critical metal-based signaling species - iron. In addition, our findings highlight the functional importance of this poorly studied lipid subtype in enabling a variety of malignancy-associated cell phenotypes including metastasis and tumor-initiating abilities. Together, these results establish a role for ether lipids as critical effectors of cancer cell fate.

RESULTS

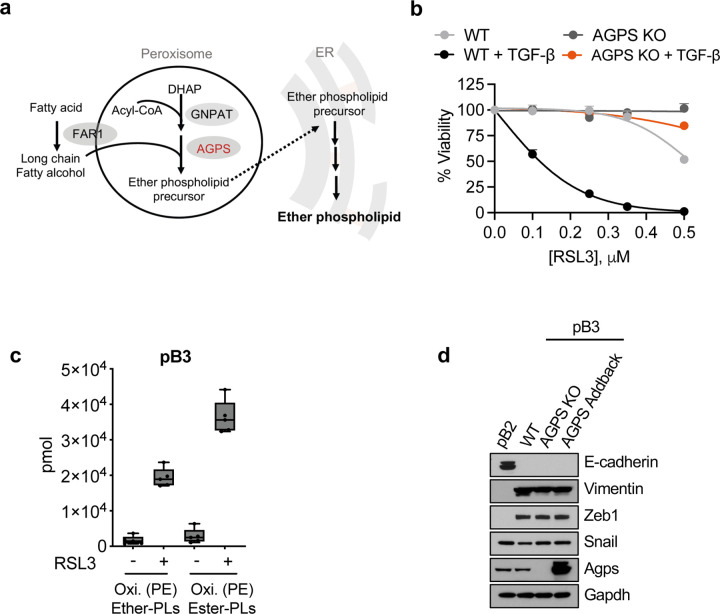

Ether lipids play a key role in maintaining a ferroptosis susceptible cell state

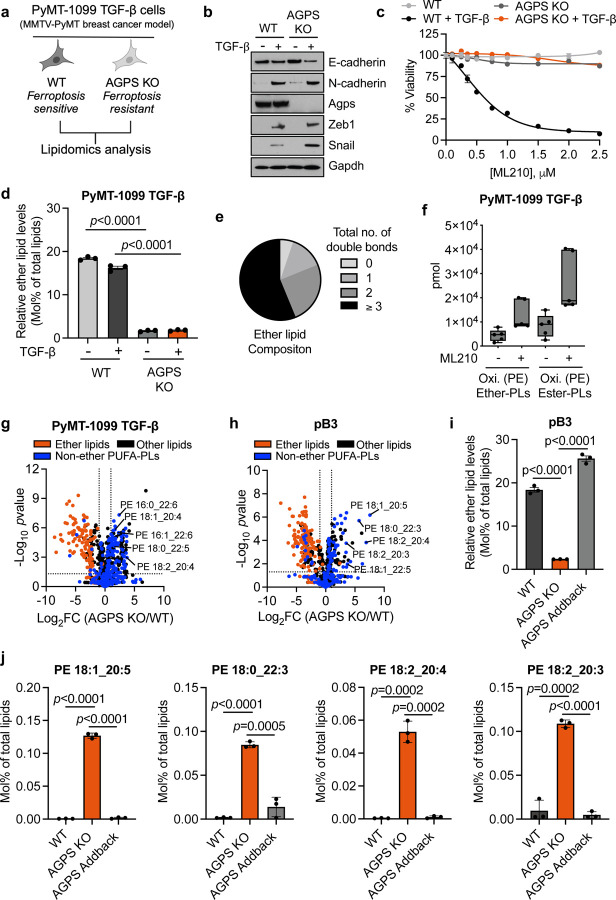

In order to investigate the mechanism(s) by which ether lipid deficiency reduces ferroptosis susceptibility, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 to knockout (KO) the AGPS gene, in ferroptosis-sensitive TGF-β-treated PyMT-1099 murine breast cancer cells26 (Fig. 1a, 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1a). The AGPS gene encodes a rate-limiting enzyme critical for ether lipid biosynthesis20. Consistent with our prior studies19, loss of ether lipids via AGPS KO significantly decreased the susceptibility of these cancer cells to ferroptosis induced by treatment with the GPX4 inhibitors ML210 or RSL3 (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Ether lipids play a key role in maintaining a ferroptosis susceptible cell state. See also Extended Data Fig.1.

a. Schematic of experimental model for lipidomic analysis.

b. Immunoblot analysis for AGPS expression in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells. Cells were treated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 10 d where indicated.

c. Cell viability following treatment with the GPX4 inhibitor ML210 for 72 h. 1099 WT or AGPS KO cells were pretreated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 10 d prior to assay. Graph is representative of two independent biological replicates.

d. Bar graph showing percent of total lipids constituted by ether lipids following AGPS KO in untreated wildtype (WT) or TGF-β-treated (2 ng/ml;10 d) PyMT-1099 cells.

e. Pie chart showing the relative proportion of ether lipids with various total numbers of double bonds.

f. Amount in pmol of oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine (Oxi. PE) ether and ester phospholipids in PyMT-1099 TGF-β cells treated with ML210 for 24 h. Five biological replicates per condition.

g. Volcano plot showing the log2 fold change in the relative abundance of various lipid species upon knockout of AGPS in PyMT-1099 TGF-β-treated cells. Blue indicates non-ether linked polyunsaturated phospholipids with a total of at least 3 double bonds; orange indicates all ether lipids identified in lipidomic analysis and black denotes all other lipids identified.

h. Volcano plot showing the log2 fold change in the relative abundance of various lipid species upon knockout of AGPS in pB3 cells. Blue indicates non-ether linked polyunsaturated phospholipids with a total of at least 3 double bonds; orange indicates all ether lipids identified in lipidomic analysis and black denotes all other lipids identified.

i. Bar graph showing the percent of total lipids constituted by ether lipids in pB3 WT, pB3 AGPS KO and pB3 AGPS addback cells.

j. Bar graph showing the effects of ether lipids on the relative abundance of selected polyunsaturated diacyl phospholipids in pB3 cells.

Unless stated otherwise, all samples were analyzed in technical triplicates and shown as the mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test. For figures 1h–1j: pB3 WT and AGPS KO cells were transduced with the respective vector control plasmids. pB3 AGPS addback cells are derivatives of AGPS KO cells transduced with a murine AGPS expression vector.

By performing lipidomic analysis, we validated that knockout of AGPS resulted in a significant reduction in total ether abundance in these cells (Fig. 1d). More than half of the identified ether lipids contained polyunsaturated fatty acyl groups which are highly prone to free radical attack (Fig. 1e). Based on this observation, we speculated that loss of ether lipids could attenuate ferroptosis susceptibility by depleting the pool of available ether lipid substrates for lipid peroxidation. Therefore, we performed oxidized lipidomic analysis on two ferroptosis-sensitive breast cancer cell lines that were treated with a GPX4 inhibitor. These experiments indicated that ether lipids could indeed be oxidized following ferroptosis induction (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Given that ether lipids only constitute about ~20% of total lipids, we also investigated whether the relative abundance of non-ether-linked polyunsaturated phospholipids, were impacted by loss of ether lipids. Surprisingly, our analyses revealed that ether lipid deficiency actually increased the relative abundance of several polyunsaturated diacyl phospholipids with putative pro-ferroptosis function27, 28 (Fig. 1g). To ensure that these findings were not an idiosyncrasy of our TGF-β-treated PyMT-1099 AGPS KO cells, we confirmed this observation in PyMT-MMTV-derived pB3 murine AGPS KO breast cancer cells29 (Fig. 1h, 1i, Extended Data Fig. 1d). Importantly, re-expression of AGPS (i.e., “addback”) could restore the relative levels of these non-ether-linked polyunsaturated diacyl phospholipids to levels comparable to pB3 WT cells (Fig. 1j). These findings strongly argue against the notion that ether deficiency attenuates ferroptosis susceptibility simply by decreasing the global level of polyunsaturated phospholipids and further underscores the importance of polyunsaturated ether phospholipids in maintaining a ferroptosis susceptible cell state.

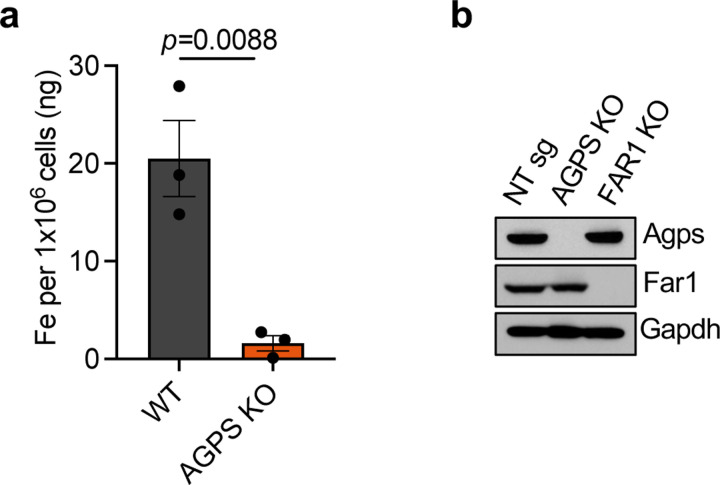

Ether lipids regulate cellular redox-active iron levels in cancer cells

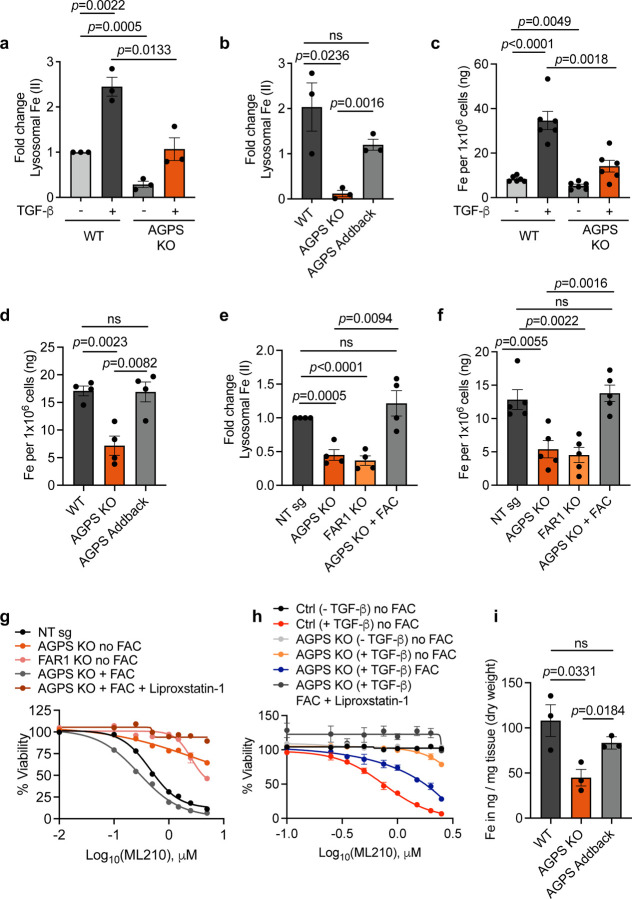

The above observations together with our oxidized ether phospholipidomic analysis supported the notion that ether lipids could modulate ferroptosis susceptibility, at least in part, by serving as substrates for lipid peroxidation. These observations, however, failed to address the formal possibility that alterations of ether lipid composition could also affect intracellular levels of redox-active iron, the central mediator of the lipid peroxidation that drives ferroptosis. For this reason, we investigated whether alterations in ether lipid composition actually affected the intracellular levels of redox-active iron. To address this possibility, we used two orthogonal analyses to assess intracellular iron levels. Since the endolysosomal compartment is a key reservoir of iron within cells30–32, we used a lysosomal iron (II)-specific fluorescent probe, RhoNox-M33, to gauge the levels of iron within these cells. In addition, we used inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantify total intracellular iron levels32, 34, 35.

Remarkably, loss of AGPS reduced intracellular iron levels in all murine cancer cell lines tested, whereas re-expression of AGPS (i.e., “addback”) restored intracellular iron to levels comparable to those seen in parental ferroptosis-sensitive cancer cells (Fig. 2a–2d, Extended Data Fig. 2a). This provided the first indication that changes in ether phospholipids directly affect the levels of intracellular iron. Indeed, there was no direct precedent for the ability of a membrane-associated phospholipid to serve as an enhancer of the levels of an intracellular metal ion.

Fig. 2. Ether lipids regulate cellular redox-active iron levels in cancer cells. See also Extended Data Fig. 2.

a. Relative lysosomal iron levels based on Rhodox-M fluorescence intensity normalized to the fluorescence intensity of lysotracker. Fold change is calculated relative to untreated PyMT-1099 wild-type (WT) cells.

b. Relative lysosomal iron levels based on Rhodox-M fluorescence intensity normalized to the fluorescence intensity of lysotracker. Fold change is calculated relative to pB3 WT cells.

c. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of cellular iron in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d.

d. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of cellular iron in pB3 cell line derivatives.

e. Relative lysosomal iron levels in OVCAR8 NT sg, FAR1 KO or AGPS KO cells pretreated with FAC (50 µg/ml) for 24 h. Data shown are based on Rhodox-M fluorescence intensity normalized to lysotracker fluorescence intensity. Fold change is calculated relative to NT sg.

f. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of cellular iron in OVCAR8 NT sg, FAR1 KO or AGPS KO cells pretreated with FAC (50 µg/ml) for 24 h.

g. Cell viability of OVCAR8 NT sg, FAR1 KO or AGPS KO cells pretreated with FAC (50 µg/ml) for 24 h followed by ML210 treatment for 72 h.

h. Cell viability in response to ML210 treatment. PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells were pretreated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 10 days followed by FAC treatment (100 µg/ml) for an additional 24 h. Cells were then treated with ML210 in the presence or absence of liproxstatin-1 (0.2µM) and cell viability was assessed after 72 h.

i. ICP-MS of cellular iron from primary tumors derived from pB3 WT, pB3 AGPS KO, and pB3 AGPS addback cells. Mean +/− SEM from 3 independent tumor samples per condition. Each datapoint represents the average iron measurement from 5 technical replicates per tumor sample.

All samples were analyzed with 3–6 technical replicates and shown as the mean +/− SEM unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Abbreviation: NT – nontargeting.

Supporting this conclusion, we found that a reduction in the levels of ether lipids, achieved via knockout of the genes encoding either the AGPS or the fatty acid reductase 1 (FAR1) enzymes20 (Extended Data Fig. 2b), also resulted in a significant decrease in intracellular iron levels, in this case in the mesenchymal-enriched OVCAR8 human high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell line (Fig. 2e, 2f). Furthermore, we noted that treatment of AGPS KO cells with ferric ammonium citrate (FAC)36, 37, which provides an exogenous source of ferric ions re-sensitized cultured AGPS KO mesenchymal breast and ovarian carcinoma cells to ferroptosis induction, doing so even in the absence of elevated ether phospholipids (Fig. 2g, 2h).

We further extended this analysis by studying the behavior of mammary carcinoma cells forming tumors in vivo. Consistent with our in vitro data, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry indicated that total iron levels are reduced in breast tumors derived from implanted pB3 AGPS KO carcinoma cells relative to those arising from pB3 wildtype (WT) or control pB3 AGPS-addback cells (Fig. 2i). Such observations reinforced the notion that ether lipids are critical regulators of intracellular iron levels, a rate-limiting component of ferroptosis.

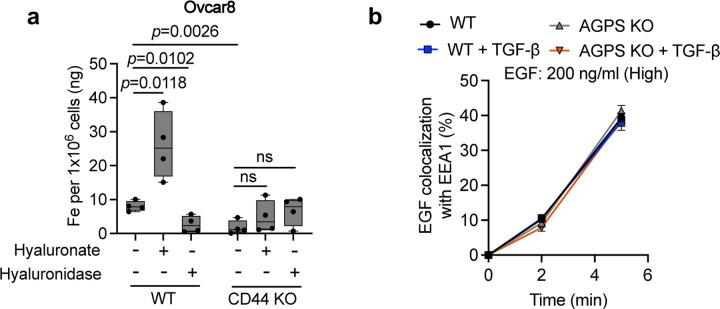

Ether lipids facilitate CD44-mediated iron endocytosis

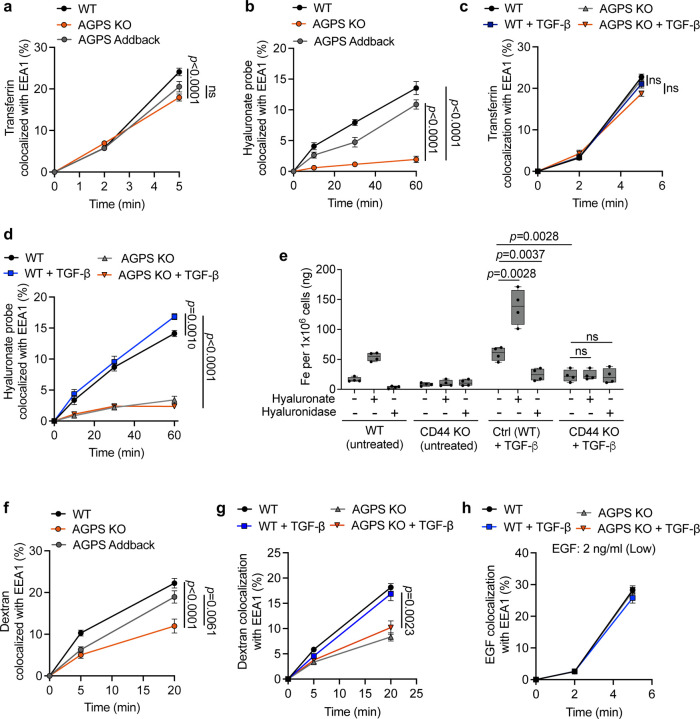

We proceeded to investigate the mechanism(s) by which membrane-associated ether lipids regulate intracellular iron content. This led us to examine the behavior of two proteins that act as major mediators of cellular iron import - transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)38 and CD4432 – and whether their functioning was altered in response to loss of ether phospholipids. While CD44 is best known as a cell-surface cancer stem-cell marker39, 40, recent research revealed its critical role in mediating endocytosis of iron-bound hyaluronates in CSC-enriched cancer cells and in activated immune cells32, 41. To monitor these two alternative iron import mechanisms, we performed endocytosis kinetics experiments using fluorescently labeled transferrin as a proxy for TfR1 internalization and fluorescently labeled hyaluronic acid (HA), whose main plasma membrane receptor is CD44, as a marker for CD44 internalization42, 43.

Here we observed that the rate of endocytosis of TfR1 was marginally affected by a deficiency of ether lipids in pB3 breast cancer cells (Fig. 3a). In stark contrast, CD44-mediated endocytosis was significantly impaired when the AGPS gene was knocked out in this ether lipid-deficient, cancer cells (Fig. 3b). Conversely, CD44-dependent iron import could be restored to normal levels by introduction of a functional AGPS gene into these AGPS KO cells (Fig. 3b). Reduction in the rate of internalization of CD44 but not TfR1 could also be observed in ether lipid-deficient PyMT-1099 TGF-β-treated breast cancer cells (Fig. 3c, 3d). Hence, in these cells, ether lipids played a critical role in modulating intracellular iron concentration by regulating endocytosis of CD44 but not transferrin receptor. These findings were consistent with our previous observations that TfR1 and CD44 localize to distinct endocytic vesicles in CSC-enriched cancer cells32, 44 making plausible that their internalization was governed by independent endocytic mechanisms.

Fig. 3. Ether lipids facilitate CD44-mediated iron endocytosis. See also Extended Data Fig. 3.

a. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled transferrin as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in pB3 cells.

b. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled hyaluronate probe as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in pB3 cells.

c. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled transferrin as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d.

d. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled hyaluronate probe as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d.

e. ICP-MS of cellular iron following treatment with either hyaluronan or hyaluronidase in PyMT-1099 WT or CD44 KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d.

f. Endocytic transport of dextran as assessed by quantitative colocalization with the early endosomal marker EEA1 in pB3 cells.

g. Endocytic transport of dextran as assessed by quantitative colocalization with the early endosomal marker EEA1 in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d.

h. Endocytosis of EGFR as assessed by quantitative colocalization of internalized EGF with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 days. Cells were treated with 2 ng/ml EGF.

All data shown as mean +/− SEM and statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test; Examined n=10 fields of cells per experimental sample for all endocytosis-related experiments and n=4 replicates for ICP-MS.

To further support the role of CD44 in promoting iron uptake – acting via its endocytosis of HA – we demonstrate that knocking out the gene encoding CD44 or, alternatively, treating cancer cells with hyaluronidase, led to a significant reduction in intracellular iron levels (Fig. 3e). Conversely, supplementing these cells with hyaluronic acid increased intracellular iron levels (Fig. 3e). Similar observations were seen in human OVCAR8 cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Taken together, these observations further supported the influential role of CD44 in mediating iron uptake in these cancer cells32.

We then studied whether the observed defect in CD44 endocytosis observed in ether lipid deficient cells was limited to CD44 or, instead, reflected a general impairment in the endocytosis of a variety of plasma membrane-associated glycoproteins. In fact, CD44 is known to undergo a type of clathrin- and dynamin-independent form of endocytosis44–46. This alternative mechanism of endocytosis differs from the one regulating TfR1 recycling, which undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis, in which small invaginations of clathrin-coated pits undergo scission facilitated by the GTPase dynamin45, 47.

To test whether loss of ether phospholipids had a wider effect on the clathrin- and dynamin-independent mode of endocytosis, we examined the rate of uptake of dextran (70 kDa), a branched polysaccharide known to undergo endocytosis by a clathrin-independent mechanism45. Similar to CD44, we observed that loss of AGPS also exhibited a significant reduction in the rate of dextran endocytosis; this behavior could be reversed by restoration of ether phospholipids levels achieved by AGPS complementation (Fig. 3f, 3g). Moreover, the loss of ether lipids had a negligible effect on the rate of EGFR endocytosis which, like TfR1, is known to rely on clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Fig. 3h, Extended Data Fig. 3b).

Hence, these observations reinforced the notion that the internalization of extracellular and cell-surface molecules is mediated by at least two distinct mechanisms that differ in their dependence on ether phospholipids. More specifically, these findings provided strong support for the involvement of a widely acting clathrin- and dynamin-independent form of endocytosis, on which CD44 internalization depended32, 48–50 and is significantly compromised in ether lipid-deficient cells.

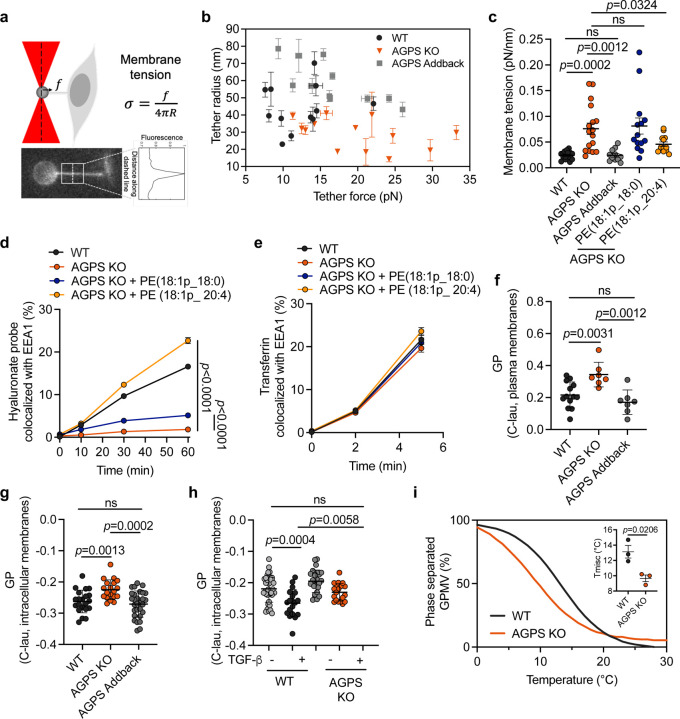

Ether lipid deficiency impairs membrane biophysical properties

The above observations did not provide mechanistic insights into how changes in the composition of membrane ether lipids could exert an effect on CD44 internalization. As observed by others, non-clathrin-mediated endocytosis, which is employed by CD44, is particularly sensitive to changes in the physicochemical properties of the lipid bilayer forming plasma membranes46, 51–56. Such changes can influence membrane tension, membrane fluidity and stability, and formation of lipid rafts, all of which, in turn, impact the assembly and dynamics of clathrin-independent, cell-surface endocytic structures. Hence, we hypothesized that ether lipids alter the biophysical properties of the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane to facilitate elevated iron endocytosis via CD44.

Membrane deformability can be gauged by the parameter of membrane tension, which measures the forces exerted on a defined cross-section of the plasma membrane. It is influenced by both the in-plane tension of the lipid bilayer and the attachment of the plasma membrane to the underlying cell cortex57, 58. Indeed, alterations in membrane tension have long been demonstrated to affect endocytosis59–64, prompting us to assess the effects of loss of ether lipids on plasma membrane tension. To quantify membrane tension directly, we generated a membrane tether using an optically trapped bead and measured the pulling force (f) and the tube radius (R) to calculate membrane tension (σ) of living cells48, 65 (Fig. 4a, 4b). We found that depletion of ether phospholipids led to a significant increase in membrane tension in pB3 AGPS KO cells relative to the corresponding pB3 WT cancer cells (Fig. 4c). This shift was largely attenuated upon restoration of AGPS expression in pB3 AGPS KO cells or upon exposure of cultured cells to liposomes composed of polyunsaturated ether phospholipids (Fig. 4c). Treatment of pB3 AGPS KO cells with these ether lipid-containing liposomes also increased the rate of CD44 endocytosis to levels comparable to those of pB3 WT cells (Fig. 4d). No changes were observed in the rate of clathrin-dependent TfR1 endocytosis under these conditions (Fig. 4e). Taken together, these results provided the first indication that ether lipids facilitate CD44-mediated iron endocytosis in cancer cells, in part, by decreasing membrane tension.

Fig. 4. Ether lipid deficiency impairs membrane biophysical properties.

a. Schematic of membrane tether pulling assay and fluorescence image showing a tether pulled from the plasma membrane of a pB3 cell using an optically trapped 4 µm anti-Digoxigenin coated polystyrene bead.

b. Graph showing tether radius (R) and tether force measurements (f) in pB3 WT, AGPS KO, and AGPS addback cells. All data shown as mean +/− SD.

c. Membrane tension measurements in pB3 WT, AGPS KO pretreated with 20µM of the indicated ether phospholipid liposomes, and AGPS addback cells. All data shown as mean +/− SEM.

d. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled hyaluronate probe as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in pB3 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 20µM of the indicated ether phospholipid liposomes. All data shown as mean +/− SEM.

e. Endocytic transport of fluorescently labeled transferrin as assessed by quantitative colocalization with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in pB3 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 20µM of the indicated ether phospholipid liposomes. All data shown as mean +/− SEM.

f. GP values of C-Laurdan-labeled plasma membranes from pB3 WT, AGPS KO and AGPS addback cells. Data is shown as mean GP +/− SD.

g. GP values of C-Laurdan-labeled intracellular membranes from pB3 WT, AGPS KO and AGPS addback cells. Data is shown as mean GP +/− SD.

h. GP maps of C-Laurdan-labeled intracellular membranes from PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells treated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d. Data shown as mean GP +/− SD.

i. Representative curves showing a leftward shift of the phase separation curve in GPMVs from pB3 AGPS KO cells in comparison to wildtype pB3 control cells. This is indicative of less stable phase separation upon loss of AGPS. Curves were generated by counting >/= 20 vesicles/temperature/condition at >4 temperature. The data was fit to a sigmoidal curve to determine the temperature at which 50% of the vesicles were phase-separated (Tmisc). Data shown as the average fits of 3 independent experiments. Inset showing a decrease in miscibility transition temperatures (Tmisc) upon loss of AGPS in pB3 cells. Graph shows the mean +/− SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

Membrane lipid packing can also impact endocytosis66–68. It is related to the fluidity or viscosity of the lipid bilayer, with higher lipid packing correlating with higher viscosity. This, in turn, affects the ease with which proteins and lipids undergo lateral diffusion and conformational changes within a lipid bilayer, thereby affecting endocytosis-related signaling48. This motivated us to investigate the contribution of ether lipids to membrane lipid packing. To do so, we used the C-laurdan lipid-based, polarity-sensitive dye, which yields a spectral emission shift dependent on the degree of lipid packing69. These measurements are used to calculate a unitless index, termed generalized polarization (GP), where a higher GP indicates increased lipid packing69. Our measurements using the C-laurdan dye indicated that a reduction in ether lipid levels resulted in a measurable, significant increase in membrane packing (Fig. 4f–4h), which, like increase increases in membrane tension, negatively affects membrane plasticity66.

A third parameter governing the biophysical properties of lipid bilayers involves the stability (size and lifetime) of lipid rafts. This parameter can be gauged by monitoring the miscibility transition temperature (Tmisc) of these membranes70. The association of CD44 with lipid rafts, which are dynamically formed plasma membrane microdomains, is known to be critical for CD44-mediated HA endocytosis71. We reasoned that a decrease in the stability of lipid rafts, and thus a decrease in Tmisc, would result in impairment of CD44 endocytosis70. Thus, we measured the effect of loss of ether lipids on the miscibility transition temperature. In fact, we observed a decrease in Tmisc upon loss of AGPS in pB3 cancer cells, which indicated a decrease in lipid raft stability. This finding supports a role for ether lipids in maintaining the plasma membrane organization through lipid raft microdomains (Fig. 4i), revealing yet another biophysical property of lipid bilayers that can influence CD44 endocytosis.

It is noteworthy that clathrin-independent endocytosis exhibits a greater dependency on the membrane biophysical properties assessed above46, 51–56. This may explain why loss of ether lipids can exert a significant effect on the rate of CD44-mediated iron endocytosis but negligible effects on the clathrin-mediated TfR1 endocytosis. Furthermore, these findings illuminated a mechanism by which membrane-associated ether lipids could govern a major mechanism of iron internalization, which in turn could impact the vulnerability of cancer cells to ferroptosis inducers.

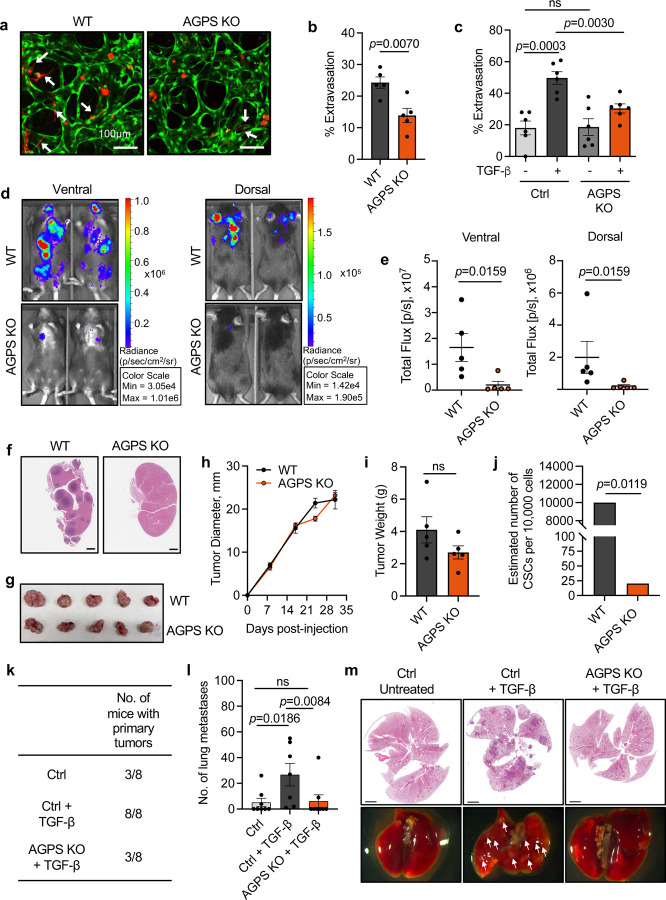

Loss of ether lipids decreases metastasis and cancer cell stemness

Prior studies have demonstrated that reduced membrane tension and elevated intracellular iron can promote cancer metastasis72–76. These findings of others caused us to investigate whether changes in the ether lipid composition of cancer cells impacted key steps of the multi-step invasion-metastasis cascade, notably extravasation efficiency, post-extravasation proliferation77, as well as the functionally critical trait of cancer cell stemness, i.e., tumor-initiating ability.

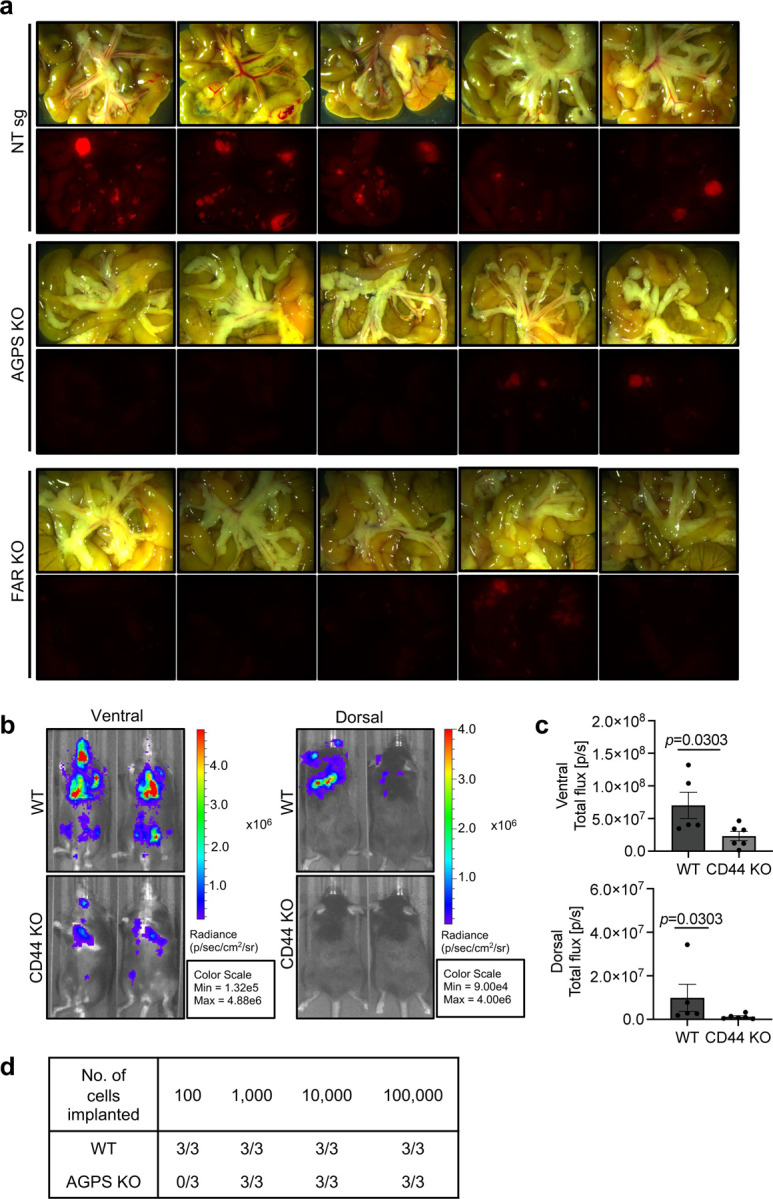

We measured extravasation efficiency by employing an in vitro three-dimensional microvascular network system composed of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and normal human lung fibroblasts. This system has been shown to accurately model some of the complex biological processes associated with cancer cell extravasation78–82. Using this defined experimental system, we found that loss of ether lipids significantly decreased extravasation efficiency (Fig. 5a–5c). Furthermore, we observed a strong reduction in overall metastatic burden following intracardiac injection in syngeneic hosts of the pB3 AGPS KO breast cancer cells relative to corresponding wildtype cells (Fig. 5d–5f). As an important control in these experiments, we determined that ether lipid deficiency in these cells had a modest effect on primary tumor growth kinetics, making it unlikely that the loss of ether phospholipids had a significant effect on post-extravasation proliferation of disseminated tumor cells (Fig. 5g–5i). A decrease in metastatic burden was also observed upon knockout of AGPS and FAR1 in OVCAR8 cancer cells, and upon loss of CD44 in pB3 cancer cells (Extended Data Fig. 4a–4c).

Fig. 5. Loss of ether lipids decreases metastasis and cancer cell stemness. See also Extended Data Fig. S4.

a. Representative confocal images of extravasated tdTomato-labeled pB3 WT and AGPS KO cells from an in vitro microvascular network established using HUVEC (green) and normal human lung fibroblasts (unlabeled), over a time period of 24 h.

b. Quantification of extravasated tdTomato-labeled pB3 WT and AGPS KO cells from an in vitro microvascular network established using HUVEC (green) and normal human lung fibroblasts (unlabeled), over a time period of 24 h. Each datapoint represents number of extravasated cells per device. Data is representative of two independent biological replicates. Graph shows the mean +/− SEM and statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

c. Quantification of extravasated tdTomato-labeled PyMT-1099 cell line derivatives from an in vitro microvascular network established using HUVEC (green) and normal human lung fibroblasts (unlabeled), over a time period of 24 h. Each datapoint represents number of extravasated cells per device. Data is representative of two independent biological replicates. Graph shows the mean +/− SEM and statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

d. Representative IVIS images of overall metastatic burden in C57BL/6 female mice following intracardiac injection of GFP-luciferized pB3 WT (n=5) and AGPS KO (n=5) cells. Mean +/− SEM.

e. Quantification of overall metastatic burden in C57BL/6 female mice following intracardiac injection of GFP-luciferized pB3 WT (n=5) and AGPS KO (n=5) cells. Mean +/− SEM.

f. Representative images of H&E-stained sections of harvested kidneys from C57BL/6 female mice following intracardiac injection of pB3 WT or pB3 AGPS KO cells.

g. Gross images of primary tumors derived from pB3 WT control cells and pB3 AGPS KO cells.

h. Tumor growth kinetics of primary tumors derived from pB3 WT control cells and pB3 AGPS KO cells. (n=5 mice per group).

i. Bar graph showing the average weight from primary tumors derived from pB3 WT control cells and pB3 AGPS KO cells. Data shows the mean +/− SEM.

j. Estimated number of cancer stem cells (CSCs) per 10,000 cells as calculated by extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software. Tumor-initiating capacity was assessed following implantation of indicated amounts of pB3 WT or pB3 AGPS KO cells into the mammary fat pad of C57BL/6 mice. P values, χ2 pairwise test.

k. Table showing the number of mice with palpable primary tumors at 121 d post orthotopic implantation of PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d into NSG female mice.

l. Quantification of lung metastases for aforementioned experiment. Data shows the mean number of lung metastases +/− SEM.

m. Representative images of H&E-stained lungs harvested from C57BL/6 female mice following orthotopic injection of PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 d. Lungs were harvested after 121 d post-injection.

Given that high CD44 expression and elevated intracellular iron levels are positively correlated with cancer cell stemness32, 39, 83, we investigated whether ether lipid deficiency also affects the tumor-initiating capacity of cancer cells as gauged by an experimental limiting dilution tumor-implantation assay. These experiments indicated that loss of ether lipids in pB3 breast cancer cells decreases cancer cell stemness (Fig. 5j, Extended Data Fig. 4d), which, as we have found in other investigations, serve as a reliable marker of metastasis-initiating capacity84. In addition, we found that loss of ether lipids significantly attenuates the tumor-initiating potential and metastatic capacity of PyMT-1099 AGPS KO TGF-β-treated (ether lipid deficient) cancer cells following implantation into the orthotopic site –– the mammary stromal fat pad (Fig. 5k–5m). Hence, ether lipids play critical roles in promoting cancer cell stemness and resulting post-extravasation colonization.

DISCUSSION

The present findings indicate the need to consider the complex interplay between genetics and the biophysical properties of cell membranes as determinants of cancer cell fate and emphasize the potential role of lipids and metals in this process. Membrane-associated phospholipids have previously been implicated as important mediators of cell transformation, in large part through the actions of inositol phospholipids and their derivatives85. In the present study, we shed light on an entirely different and poorly studied role of lipids in influencing cell fate through their effects on membrane biophysical properties and their impact on iron homeostasis. Specifically, we uncover a mechanism whereby alterations in ether lipids affect the biophysical properties of the plasma membrane to impact distinct cell-biological processes –– iron uptake and neoplasia-related phenotypes, notably metastasis and cancer cell stemness/tumor-initiating ability. Importantly, this biochemical configuration creates a unique vulnerability of cancer cells to ferroptosis, and suggests that targeting lipid metabolism and iron homeostasis could be exploited to suppress subpopulations of highly metastatic and drug-tolerant carcinoma cells86.

Ether phospholipids have been widely portrayed as participants in ferroptosis through their role as substrates prone to iron-catalyzed peroxidation. However, our findings indicate an entirely different mechanism whereby ether lipids directly modulate the levels of intracellular iron, a rate-limiting component governing ferroptosis susceptibility4, 32, 73. By emphasizing the role of membrane biophysical properties in governing iron uptake, we depart from the conventional focus limited to portraying phospholipids as substrates for peroxidation. This shift in perspective has the potential to open new avenues for research, as it challenges researchers to explore the biophysical aspects of membranes as a new dimension in the regulation of this cell death program.

Alterations in intracellular iron level can impact gene expression via various mechanisms including modulation of chromatin-modifying enzyme activity32, 87, 88. For example, increase of intracellular iron levels has been shown to promote the activity of iron-dependent demethylases32, 87, 88, impacting gene expression profiles underlying cell plasticity32 and immune cell activation41. Our finding that ether lipid deficiency reduces intracellular iron levels explains, at least in part, how loss of ether lipids may impact cancer-associated transcriptional programs, acting at the epigenetic level and enabling a variety of malignancy-associated cell phenotypes including metastasis and cancer stemness. Such mechanisms may act in concert with non-iron-dependent processes, which are also regulated by ether lipids to affect cancer malignancy traits.

The implications of our research findings may extend far beyond the realm of cancer pathogenesis. We speculate that the biophysical modulation of membranes and its intersection with iron biology could be a widely-acting determinant of cell fate, impacting processes such as differentiation, immune activation, wound healing, and embryonic development.

METHODS

Cell lines

The pB3 MMTV-PyMT-derived murine breast cancer cell line was a kind gift from the laboratory of Harold L. Moses29. 687g cells (also called EpCAMLoSnail-YFPHi) were originally established from tumors that developed in the MMTV-PyMT-Snail-IRES-YFP reporter mouse model, previously developed by the Weinberg lab89. pB3 and 687g cell lines were cultured in 1:1 DMEM/F12 medium containing 5% adult bovine serum with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% non-essential amino acids29. The PyMT-1099 murine breast cancer cell line was a kind gift from the laboratory of Gerald Christofori and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% glutamine26. These cells were treated with 2 ng/ml of TGF-β for 10 days, prior to performing any subsequent analyses. OVCAR8 cells were obtained from the laboratory of Joan Brugge and cultured in 1:1 MCDB 105 medium/Medium 199 Earle’s Eagles medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. All cells were negative for mycoplasma. Human cell line authentication (CLA) analysis of OVCAR8 cells were performed by the Duke University DNA Analysis facility. Established murine lines have not been STR profiled.

Animal studies

All animal studies were conducted according to the MIT Committee on Animal Care protocol. For primary tumor growth studies: 1 million cells were resuspended in 20% Matrigel/PBS and injected into the mammary fat pad of 6–8 weeks old female mice. C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used for in vivo experiments with pB3 cells. NSG mice were used for in vivo experiments with PyMT-1099 cells. These cells were pretreated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 10 days prior to injection. Tumor size was measured once a week using a vernier caliper and tumor volume was calculated using the formula: Tumor volume = length x width2/2, where length represents the largest tumor diameter and width represents the perpendicular tumor diameter. For limiting dilution tumor-initiating assays: pB3 WT or pB3 AGPS KO cells were resuspended in 20% Matrigel/PBS and injected into the mammary fat pad of 6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) at the following dilutions: 100,000, 10,000, 1000, 100 cells. Animals were assessed for palpable tumors after 39 days post injection. The estimated number of CSCs was calculated using the extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software. For experimental metastasis involving pB3 cell lines, 0.2 million cells were resuspended in 200µl of PBS and injected into the left ventricle of 6–8 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice. Metastatic burden was measured after 10 d post-injection via bioluminescence in live animals using the IVIS Spectrum in vivo imaging system. Images were analyzed using Living Image software (PerkinElmer). For OVCAR8 cells, 1.5 million cells were resuspended in PBS and implanted into 6–8 weeks old female athymic nude mice (Jackson Laboratories) via intraperitoneal injections. Metastatic burden was assessed after 6 weeks using a fluorescence dissecting microscope.

Generation of gene-edited cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9

With the exception of OVCAR8 cells, all AGPS KO single cell clones were generated via transient transfection with mouse AGPS CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmids (Catalog no. sc-432759, Santa Cruz) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GFP-positive cells were sorted via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) into 96-well plates with one cell per well and single cell clones were subsequently expanded. AGPS KO single cell clones were assessed for loss of AGPS expression via western blot analysis. pB3 AGPS addback cells were generated by transducing AGPS KO single cell clone with pLV[Exp]-Puro-EF1A-mAgps lentiviral vector (VectorBuilder). pB3 AGPS KO cells expressing pLV[Exp]-Puro-EF1A-Stuffer_300bp (VectorBuilder) were established as controls and noted as pB3 AGPS KO + EV in the manuscript. Lentivirus was produced by transfecting HEK293T cells with viral envelope (VSVG, Addgene) and packaging plasmids (psPAX2, Addgene). Viral supernatant was collected after 48 h and filtered through a 0.45µm filter. Stably transduced cells were selected with 2 µg/ml puromycin. OVCAR8 FAR1 KO and AGPS KO single cell clones as well as nontargeting control cells, were established as previously described19. pB3 CD44 KO cells (bulk) were generated using human CD44 CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmids (Catalog no. sc-419558, Santa Cruz) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h post-transfection, cells were sorted by flow cytometry for GFP positive cells, expanded in culture, and resorted twice for CD44 negative cells using Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-mouse/human CD44 Antibody. Cells were maintained as bulk CD44 KO cells.

| Plasmids | Source |

|---|---|

| pLV[Exp]-Puro-EF1A-Agps (mouse) | VectorBuilder |

| pLV[Exp]-Puro-EF1A-Stuffer_300bp | VectorBuilder |

| Mouse AGPS CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmids | Catalog no. sc-432759, Santa Cruz |

| Mouse CD44/HCAM CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmids | Catalog no. sc-419558, Santa Cruz |

| LentiCRISPRv2-puro-Nontargeting | Published19 |

| LentiCRISPRv2-puro-human AGPS sg | Published19 |

| LentiCRISPRv2-puro-human FAR1 sg | Published19 |

| pLV-EF1A-eGFP-LUC | VectorBuilder |

| pCDH-EF1-Luc2-P2A-tdTomato | Plasmid #72486, Addgene |

Lipidomics analysis

Lipid extraction for mass spectrometry lipidomics

Mass spectrometry-based lipid analysis was performed by Lipotype GmbH (Dresden, Germany) as described90. Lipids were extracted using a chloroform/methanol procedure91. Samples were spiked with internal lipid standard mixture containing: cardiolipin 14:0/14:0/14:0/14:0 (CL), ceramide 18:1;2/17:0 (Cer), diacylglycerol 17:0/17:0 (DAG), hexosylceramide 18:1;2/12:0 (HexCer), lyso-phosphatidate 17:0 (LPA), lyso-phosphatidylcholine 12:0 (LPC), lyso-phosphatidylethanolamine 17:1 (LPE), lyso-phosphatidylglycerol 17:1 (LPG), lyso-phosphatidylinositol 17:1 (LPI), lyso-phosphatidylserine 17:1 (LPS), phosphatidate 17:0/17:0 (PA), phosphatidylcholine 17:0/17:0 (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine 17:0/17:0 (PE), phosphatidylglycerol 17:0/17:0 (PG), phosphatidylinositol 16:0/16:0 (PI), phosphatidylserine 17:0/17:0 (PS), cholesterol ester 20:0 (CE), sphingomyelin 18:1;2/12:0;0 (SM), triacylglycerol 17:0/17:0/17:0 (TAG). After extraction, the organic phase was transferred to an infusion plate and dried in a speed vacuum concentrator. The dry extract was re-suspended in 7.5 mM ammonium formiate in chloroform/methanol/propanol (1:2:4, V:V:V). All liquid handling steps were performed using Hamilton Robotics STARlet robotic platform with the Anti Droplet Control feature for organic solvents pipetting.

MS data acquisition

Samples were analyzed by direct infusion on a QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a TriVersa NanoMate ion source (Advion Biosciences). Samples were analyzed in both positive and negative ion modes with a resolution of Rm/z=200=280000 for MS and Rm/z=200=17500 for MSMS experiments, in a single acquisition. MSMS was triggered by an inclusion list encompassing corresponding MS mass ranges scanned in 1 Da increments92. Both MS and MSMS data were combined to monitor CE, DAG and TAG ions as ammonium adducts; LPC, LPC O-, PC, PC O-, as formiate adducts; and CL, LPS, PA, PE, PE O-, PG, PI and PS as deprotonated anions. MS only was used to monitor LPA, LPE, LPE O-, LPG and LPI as deprotonated anions; Cer, HexCer and SM as formiate adducts.

Data analysis and post-processing

Data were analyzed with in-house developed lipid identification software based on LipidXplorer93, 94. Only lipid identifications with a signal-to-noise ratio >5, and a signal intensity 5-fold higher than in corresponding blank samples were considered for further data analysis. Simple imputation of missing values was performed by replacing missing values with 0.5 * minimum non-zero value for each lipid assayed. Relative level of total ether lipids was determined by summing the pmol value of all ether lipids identified followed by normalization to total lipids.

Oxidized lipidomics

100,000 cells per condition were plated in 6-well plates 24 h prior to the experiment. For 1099, cells were treated with TGF-β for 10 d. pB3 cells were treated with 500 nM RSL3, OVCAR8 cells with 2 µM ML210 and TGF-β-treated 1099 cells with 10 µM ML210 for 24 h. Cells were subsequently washed with 1x PBS and then with 150 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Cells were then scraped and resuspended in 150 mM ammonium bicarbonate and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and cells were resuspended in 1 mL of 150 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The solutions were centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 10 min and the supernatant was removed. 200 µL of 150 mM sodium bicarbonate was added to the pellet and samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cells were prepared in 5 independent biological replicates and lipidomics analysis was performed on the same day for all the replicates. For lipidomics analysis, the 200 µL cell lysates were spiked with 1.4 μL of internal standard lipid mixture containing 300 pmol of phosphatidylcholine 17:0–17:0, 50 pmol of phosphatidylethanolamine 17:0–17:0, 30 pmol of phosphatidylinositol 16:0–16:0, 50 pmol of phosphatidylserine 17:0–17:0, 30 pmol of phosphatidylglycerol 17:0–17:0 and 30 pmol of phosphatidic acid 17:0–17:0 and subjected to lipid extraction at 4 °C, as previously described95. The sample was then extracted with 1 mL of chloroform-methanol (10:1) for 2 h. The lower organic phase was collected, and the aqueous phase was re-extracted with 1 mL of chloroform-methanol (2:1) for 1 h. The lower organic phase was collected and evaporated in a SpeedVac vacuum concentrator. Lipid extracts were dissolved in 100 μL of infusion mixture consisting of 7.5 mM ammonium acetate dissolved in propanol:chloroform:methanol [4:1:2 (vol/vol)]. Samples were analyzed by direct infusion in a QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a TriVersa NanoMate ion source (Advion Biosciences). 5 µL of sample were infused with gas pressure and voltage set to 1.25 psi and 0.95 kV, respectively. PC, PE, PEO, PCOx and PEOx were detected in the 10:1 extract, by positive ion mode FTMS as protonated aducts by scanning m/z= 580–1000 Da, at Rm/z=200=280 000 with lock mass activated at a common background (m/z=680.48022) for 30 s. Every scan is the average of 2 micro-scans, automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 1E6 and maximum ion injection time (IT) was set to 50 ms. PG and PGOx were detected as deprotonated adducts in the 10:1 extract, by negative ion mode FTMS by scanning m/z= 420–1050 Da, at Rm/z=200=280 000 with lock mass activated at a common background (m/z=529.46262) for 30 s. Every scan is the average of 2 micro-scans. Automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 1E6 and maximum ion injection time (IT) was set to 50ms. PA, PAOx, PI, PIOx, PS and PSOx were detected in the 2:1 extract, by negative ion mode FTMS as deprotonated ions by scanning m/z= 400–1100 Da, at Rm/z=200=280 000 with lock mass activated at a common background (m/z=529.46262) for 30 s. Every scan is the average of 2 micro-scans, automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 1E6 and maximum ion IT was set to 50 ms. All data was acquired in centroid mode. All lipidomics data were analyzed with the lipid identification software, LipidXplorer93. Tolerance for MS and identification was set to 2 ppm. Data were normalized to internal standards.

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 1X Cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #9803S) containing 1mM PMSF protease inhibitor (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #8553S). Protein samples were prepared with NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Cat. #NP0007), NuPage Sample Reducing Agent (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Cat. #NP0004), and heated at 70 °C for 10 minutes. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad) and blocked in 5% milk/TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight with the respective primary antibodies at 4 °C, washed with 1X TBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed using SuperSignal™ West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Cat. #34076).

Antibody information

The table below indicates the antibodies used for western blotting and flow cytometry analyses.

| Antibody | Source | Catalog No. |

|---|---|---|

| E-Cadherin | Cell Signaling Technology | 3195S |

| Zeb1 | Cell Signaling Technology | 3396S |

| N-cadherin | Cell Signaling Technology | 13116S |

| AGPS | Invitrogen | PA5-56400 |

| FAR1 | Novus Bio. | NBP1-89847 |

| Snail | Cell Signaling Technology | 3879S |

| GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | 2118S |

| CD44 (Western Blot) | Abcam | ab189524 |

| Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-mouse/human CD44 Antibody | BioLegend | 103017 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | 7074S |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | 7076S |

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well black clear bottom plates (Corning) at 2000 or 3000 cells (1099 +/− TGF-β) and 6000 cells (OVCAR8) per well. Approximately, 12–16 h post-seeding, cells were treated with various drug concentrations using an HP D300e Digital Dispenser unless stated otherwise. Cell viability was assessed at 72 h post-treatment by performing CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assays (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative viability was calculated by normalizing to untreated controls unless stated otherwise. Non-linear regression models were applied to generate the regression fit curves using GraphPad Prism. Drug compounds were purchased as indicated: RSL3 (Selleck Chem), ML210 (Sigma Aldrich), and Liproxstatin-1 (Fisher Scientific). For experiments involving ferric ammonium citrate (FAC), FAC (Sigma) was prepared fresh in sterile 1× PBS and manually added directly to cell culture media at the indicated concentrations at the time of seeding into 96-well plates. Unless stated otherwise, cells were pretreated with FAC for 24 h prior to ML210 treatment.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Cells were treated for 24 h with Hyaluronic acid (Carbosynth, FH45321, 600–1000 kDa, 1 mg/mL) or Hyaluronidase (HD, Sigma-Aldrich, H3884, 0.1 mg/mL) as indicated. Glass vials equipped with Teflon septa were cleaned with nitric acid 65% (VWR, Suprapur, 1.00441.0250), washed with ultrapure water (Sigma-Aldrich, 1012620500) and dried. Cells were harvested and washed twice with 1× PBS. Cells were then counted using an automated cell counter (Entek) and transferred in 200µL 1× PBS to the cleaned glass vials. The same volume of 1× PBS was transferred into separate vials for the background subtraction, at least in duplicate per experiment. For tumor samples, small pieces of the tumors were added into pre-weighed cleaned glass vials. Samples were lyophilized using a freeze dryer (CHRIST, 22080). Glass vials with lyophilized tumor samples were weighed to determine the dry weight for normalization. Samples were subsequently mixed with nitric acid 65% and heated at 80°C overnight. Samples were diluted with ultrapure water to a final concentration of 0.475 N nitric acid and transferred to metal-free centrifuge vials (VWR, 89049-172) for subsequent ICP-MS analyses. Amounts of metals were measured using an Agilent 7900 ICP-QMS in low-resolution mode, taking natural isotope distribution into account. Sample introduction was achieved with a micro-nebulizer (MicroMist, 0.2 mL/min) through a Scott spray chamber. Isotopes were measured using a collision-reaction interface with helium gas (5 mL/min) to remove polyatomic interferences. Scandium and indium internal standards were injected after inline mixing with the samples to control the absence of signal drift and matrix effects. A mix of certified standards was measured at concentrations spanning those of the samples to convert count measurements to concentrations in the solution. Values were normalized against cell number or dry weight.

Iron measurements using Rhodox-M

The lysosome-specific fluorescent Fe(II) probe RhoNox-M was synthesized in 3 steps according to a previously published procedure 33. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.93 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.45 (1H, dd, J = 8.5 Hz, 2.0 Hz), 7.40–7.30 (3H, m), 7.05 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 7.0 Hz), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.50–6.44 (2H, m), 5.28–5.35 (2H, m), 3.62 (6H, m), 2.97 (6H, s). MS (ESI) m/z: calcd. for C24H25N2O3 [M+H]+ 389.19, found: 389.35. Cells were incubated with 1 µM Rhonox-M for 1 h or lysotracker deep red (Thermo Fisher Scientific L12492) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 1 h. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold 1× PBS and suspended in incubation buffer prior to being analysed by flow cytometry. For each condition, at least 10000 cells were counted. Data were recorded on a BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) and processed using Cell Quest (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (FLOWJO, LLC). The signal for Rhonox-M was normalized against the signal of lysotracker of cells treated in parallel.

Endocytosis experiments

Antibody against EEA1 was purchased from BD Biosciences (Catalog no. 610456). Conjugated transferrin (mouse)-Alexa546, dextran-Alexa555, and EGF-Alexa555 were purchased from Invitrogen. Cy3-conjugated hyaluronan was synthesized in-house. Cy2- or Cy3-conjugated donkey antibodies against mouse IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. For receptor-mediated endocytosis, cells were washed with serum-free medium and then incubated in this medium with Cy3-conjugated hyaluronan (0.1 mg/ml), Alexa 555-conjugated EGF (either 2 ng/ml or 200 ng/ml), or Alexa 546-conjugated transferrin (5 μg/ml) for 1 hr at 4° C. Cells were then washed to clear unbound ligand, and shifted to 37 °C for times indicated in the figures. Cells were stained for EEA1, followed by confocal microscopy to assess the arrival of ligand to the early endosome. To assess fluid-phase uptake, Alexa 555-conjugated dextran (0.2 mg/ml) was added to complete medium and cells were incubated 37 °C for times indicated in the figures. Cells were then stained for EEA1, followed by confocal microscopy to assess the arrival of this probe to the early endosome.

Confocal microscopy

Colocalization studies were performed with the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 Inverted Microscope having a Plan-Apochromat 63× objective, the Zeiss LSM 800 with Airyscan confocal package with Zeiss URGB (488- and 561-nm) laser lines, and Zen 2.3 blue edition confocal acquisition software. For quantification of colocalization, ten fields of cells were examined, with each field typically containing about 5 cells. Images were imported into the NIH ImageJ v.1.50e software, and then analyzed through a plugin software (https://imagej.net/Coloc_2). Under the ‘image’ tab, the ‘split channels’ option was selected. Under the ‘plugins’ tab, ‘colocalization analysis’ option was selected, and within this option, the ‘colocalization threshold’ option was selected. Menders Coefficient was used for colocalization analysis. Colocalization values were calculated by the software, and expressed as the fraction of protein of interest colocalized with EEA1.

Synthesis of HA-Cy3 probe

Hyaluronic acid (HA, 2 mg, Sigma 75044, Lot #BCBM2884) was dissolved in a 1:1 solution of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and water (0.4 mL) for a stock concentration of 5 mg/mL. The polymer was sonicated under heating to ensure full solubilization. The HA solution was then diluted into HEPES (50 mM final HEPES concentration for a total reaction volume of 2 mL once all components are combined). Sulfo-Cyanine3 amine (2.36 mg, Lumiprobe) was separately dissolved in DMSO (0.236 mL) for a stock concentration of 10 mg/mL. N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 0.253 mg, Sigma) was separately dissolved in 50 mM HEPES (0.051 mL) for a stock concentration of 5 mg/mL. The HA and EDC solutions were then combined under stirring, followed by addition of the dye solution. The reaction was stirred, protected from light, at room temperature for 12 h. Following, unreacted dye was removed via Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filters (Millipore Sigma). Manufacturer guidelines were followed to select purification spin speeds and times: 14000 rcf, 15 min per wash step (water) until washes were clear and colorless. The purified HA-Cy3 probe was stored in water at 4 °C until used.

Preparation of liposomes

Ether lipid liposomes were prepared as previously described 19. C18(Plasm)-20:4PE (Catalog. no 852804) and C18(Plasm)-18:1PE (Catalog. no. 852758) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc.

Characterization of liposomes

Table shows the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity of liposomes used in this study. The average and standard deviation of three technical repeats is provided. A Malvern ZS90 Particle Analyzer was used for size measurements reported.

| Liposome | Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | Polydispersity index |

|---|---|---|

| C18(Plasm) - 20:4 PE | 174.8 ± 2.25 | 0.273 ± 0.01 |

| C18(Plasm) - 18:1 PE | 128.7 ± 2.07 | 0.287 ± 0.03 |

Membrane tension

Tether pulling experiments were performed on a home-built optical trap, following principles described elsewhere 65, 96. Briefly, 4 µm anti-Digoxigenin coated polystyrene beads (Spherotech) were trapped with a 1064 nm, Ytterbium laser (IPG Photonics) focused through a 60x 1.2 NA objective (Olympus). Forces on the beads were measured by the deflection of backscattered trapping laser light onto a lateral effect position sensor (Thorlabs) and calibrated using the viscous drag method 97. To measure tether radii (R), cell lines were transiently transfected with a membrane-targeted fluorescent protein (glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored eGFP, Addgene #32601) using a TransIT-X2 transfection kit (Mirus). Tether radius was obtained by comparing tether fluorescence to fluorescence counts from a known area of the parent cell membrane, as described 48. Tether force (f) and fluorescence measurements were performed simultaneously. Membrane tension was calculated using the following equation:

Ether lipid liposome reconstitution assays

Adherent cells were treated with ether lipid liposomes 16–18 h prior to performing respective membrane tension or endocytosis assays. Lipid liposomes were added directly to the culture medium for a final concentration of 20 µM. Cells were switched from liposome-containing media to “extracellular imaging buffer” (HEPES buffer with dextrose, NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, CaCl2) during membrane tension experiments.

Miscibility transition temperatures (Tmisc) measurements

Miscibility transition temperatures (Tmisc) measurements were performed as previously reported 98, 99. Briefly, cells were washed in PBS, and cell membranes were labeled with 5 µg/ml fluorescent disordered/nonraft phase marker FAST DiO (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min on ice. Cells were then washed twice in GPMV buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4), and then incubated with GPMV buffer supplemented with 25 mM paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 1 h at 37 °C. Vesicles were imaged at 40× on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8) under temperature-controlled conditions using a microscope stage equipped with a Peltier element (Warner Instruments). GPMVs were imaged from 4° C-28 °C, counting phase-separated and uniform vesicles at each temperature. For each temperature, 25–50 vesicles were counted and the percent of phase-separated vesicles were calculated, plotted versus temperature, and a fitted to a sigmoidal curve to determine the temperature at which 50% of the vesicles were phase-separated (Tmisc).

C-laurdan spectral imaging

C-Laurdan imaging was performed as previously described 98–102. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and stained with 10 µg/mL C-Laurdan for 10 min on ice, then imaged using confocal microscopy on a Leica SP8 with spectral imaging at 60× (water immersion, NA= X) and excitation at 405 nm. The emission was collected as two images: 420–460 nm and 470–510 nm. MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) was used to calculate the two-dimensional (2D) GP map, where GP for each pixel was calculated as previously described 102. Briefly, each image was background subtracted and thresholded to keep only pixels with intensities greater than 3 standard deviations of the background value in both channels. The GP image was calculated for each pixel using Eq.1. GP maps (pixels represented by GP value rather than intensity) were imported into ImageJ. To calculate the average PM GP, line scans drawn across individual cells. PM GP values were taken as peak GP values from the periphery of the cell, whereas internal membranes were calculated as the average of all values outside the PM peak. The average GP of the internal membranes was calculated by determining the average GP of all pixels in a mask drawn on each cell just inside of the PM.

Extravasation assay

Cells and reagents:

Immortalized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (ECs) expressing BFP82 were cultured in VascuLife VEGF Endothelial Medium (Lifeline Cell Technology). Normal human lung fibroblasts (FBs) (Lonza, P7) were cultured in FibroLife S2 Fibroblast Medium (Lifeline Cell Technology).

Microfluidic device:

3D cell culture chips (AIM Biotech) were used to generate in vitro microvascular networks (MVNs). The AIM chip body was made of cyclic olefin polymer (COP) with a type of gas-permeable plastic serving as the bottom film. AIM Biotech chips contained three parallel channels: a central gel channel flanked by two media channels. Microposts separated fluidic channels and serve to confine the liquid gelling solution in the central channel by surface tension before polymerization. The gel channel was 1.3 mm wide and 0.25 mm tall, the gap between microposts was 0.1 mm, and the width of media channels was 0.5 mm.

Microvascular network formation:

To generate perfusable MVNs, ECs and FBs were seeded into the microfluidic chip using a two-step method 103. Briefly, ECs and FBs were concentrated in VascuLife containing thrombin (4 U/mL). For the first step seeding, the outer layer EC solution was made with a final concentration of 10 ×106/mL. After mixed with fibrinogen (3 mg/mL final concentration) at a 1:1 ratio, the outer layer EC solution was pipetted into the gel inlet, immediately followed by aspirating from the gel outlet, leaving only residual solution around the microposts. For the second step, another solution with final concentrations of 5 ×106/mL ECs and 1.5 ×106/mL fibroblasts was similarly mixed with fibrinogen and then pipetted into the same chip through the gel outlet. The device was placed upside down to polymerize in a humidified enclosure and allowed to polymerize at 37 °C for 15 min in a 5% CO2 incubator. Next, VascuLife culture medium was added to the media channels and changed daily in the device. After 7 days, MVNs were ready for further experiments.

Tumor cell perfusion in MVNs:

1099 or pB3 cell line derivatives expressing pCDH-EF1-Luc2-P2A-tdTomato (Plasmid #72486, Addgene) were resuspended at a concentration of 1×106/mL in culture medium. To perfuse these tumor cells into in vitro MVNs, the culture medium in one media channel was aspirated, followed by injection of a 20 µL tumor cell suspension in the MVNs and repeated twice. Microfluidic devices were then placed at 37 °C for 15 min in a 5% CO2 incubator for 15 min. After that, the tumor cell medium was aspirated from the media channels to remove the unattached cells, and Vasculife was replenished. Devices were then placed back to the incubator. 24 h later, devices were fixed, washed, and imaged using an Olympus FLUOVIEW FV1200 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 10× objective and an additional 2× zoom-in function. Z-stack images were acquired with a 5 µm step size. All images shown are collapsed Z-stacks, displayed using range-adjusted Imaris software, unless otherwise specified. Extravasation percentage was calculated by dividing the cell number of extravasated tumor cells with the total number of tumor cells in the same imaging region of interest.

Histology

Harvested tissues were fixed by incubating with 10% neural-buffered formalin (VWR Scientific) at 4°C for 16–18 h. Fixed samples were then transferred to 70% ethanol and submitted to Hope Babette Tang Histology Facility at the Koch Institute at MIT for paraffin-embedding and H&E staining. Metastatic burden was quantified using QuPath software 104 and Image J 105.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analyses, Mann-Whitney U test or unpaired, two-tailed t-test were performed using GraphPad Prism.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig.1.

a. Schematic of peroxisomal-ether lipid biosynthetic pathway.

b. Cell viability following treatment with the GPX4 inhibitor RSL3 for 72 h. PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells were pretreated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 10 d prior to assay. Graph is representative of two independent biological replicates.

c. Amount in pmol of oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine (Oxi. PE) ether and ester phospholipids in pB3 cells treated with RSL3 for 24 hours. Five biological replicates per condition.

d. Immunoblot analysis for AGPS expression in mesenchymal-enriched pB3 WT, AGPS KO, and AGPS addback cells. pB2 cells served as a control for expression of epithelial-like markers.

Extended Data Fig. 2.

a. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of cellular iron in the mesenchymal-enriched 687g WT and AGPS KO murine breast cancer cell line.

b. Immunoblot analysis of OVCAR8 AGPS KO, FAR1 KO or nontargeting sg (control) cells.

Unless stated otherwise, all samples were analyzed in technical triplicates and shown as the mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 3.

a. ICP-MS of cellular iron following treatment with either hyaluronan or hyaluronidase in OVCAR8 WT or CD44 KO cells.

b. Endocytosis of EGFR as assessed by quantitative colocalization of internalized EGF with an early endosomal marker (EEA1) in PyMT-1099 WT or AGPS KO cells pretreated with 2 ng/ml TGF-β for 10 days. Cells were treated with 200 ng/ml EGF.

All data shown as mean +/− SEM and statistical significance was calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-test; Examined n=10 fields of cells per experimental sample for all endocytosis-related experiments and n=4 replicates for ICP-MS.

Extended Data Fig. 4.

a. Bright-field (top) and fluorescence images (bottom) showing reduced mesenteric metastases from athymic nude mice injected with tdTomato-labeled OVCAR8 NT sg, AGPS KO and FAR1 KO cells via the intraperitoneal route.

b. Representative IVIS images of overall metastatic burden in C57BL/6 female mice following intracardiac injection of GFP-luciferized pB3 WT (n=5) and CD44 KO (n=6) cells. Mean +/− SEM.

c. Quantification of overall metastatic burden in C57BL/6 female mice following intracardiac injection of GFP-luciferized pB3 WT (n=5) and CD44 KO (n=6) cells. Mean +/− SEM.

d. Table showing number of cells implanted per mice for limiting dilution assay.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Weinberg, Farese and Walther labs for insightful discussions and reagents. We are grateful to Brent Stockwell, Laurie Boyer and Fabien Sindikubwabo for helpful discussions. We acknowledge technical support from Caroline A. Lewis, Zon W. Lai and Marina Plays, the CurieCoreTech Metabolomics and Lipidomics Technology Platform at the Institut Curie, the following facilities at the Whitehead Institute: Metabolite Profiling Core, W.M. Keck Microscopy Core, Flow Cytometry Core, as well as the Koch Institute’s Robert A. Swanson (1969) Biotechnology Center, specifically the MIT Koch Institute small animal imaging core and MIT Tang Histology facility.

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health: R37GM058615 (VWH), the National Cancer Institute K99CA255844/R00CA255844 (NB), and the National Cancer Institute (RDK). Additional funding support was received from MIT Stem Cell (RAW), Brendan Bradley Gift (RAW), Nile Albright Research Foundation (RAW), Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation (RAW), Virginia, D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research Center (RAW), European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant agreement No 647973 (RR), Foundation Charles Defforey-Institut de France (RR), Ligue Contre le Cancer Equipe Labellisée (RR), Fondation Bettencourt Schueller (RR), Marble Center for Cancer Nanomedicine (PTH), Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund (WSH), Ludwig Center at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research (WSH) and the New Horizon UROP Fund/MIT (VVP).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplemental Data Fig. file S1: Lipidomic analysis of ether lipid deficient cells

REFERENCES

- 1.Levental I. & Lyman E. Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24, 107–122 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan V.S. et al. Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature 547, 453–457 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hangauer M.J. et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature 551, 247–250 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mai T.T. et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem 9, 1025–1033 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stockwell B.R. et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 171, 273–285 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W.S. & Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol 26, 165–176 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon S.J. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta P.B. et al. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 138, 645–659 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoszczak M. et al. Iron-Sensitive Prodrugs That Trigger Active Ferroptosis in Drug-Tolerant Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J Am Chem Soc 144, 11536–11545 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang W.S. et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 156, 317–331 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doll S. et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 575, 693–698 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bersuker K. et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 575, 688–692 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang W.S. & Stockwell B.R. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol 15, 234–245 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon S.J. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife 3, e02523 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q. et al. Inhibition of neuronal ferroptosis protects hemorrhagic brain. JCI Insight 2, e90777 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang X. et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 2672–2680 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Y. et al. Hepatic transferrin plays a role in systemic iron homeostasis and liver ferroptosis. Blood 136, 726–739 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedmann Angeli J.P. et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol 16, 1180–1191 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou Y. et al. Plasticity of ether lipids promotes ferroptosis susceptibility and evasion. Nature (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Dean J.M. & Lodhi I.J. Structural and functional roles of ether lipids. Protein Cell 9, 196–206 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamin D.I. et al. Ether lipid generating enzyme AGPS alters the balance of structural and signaling lipids to fuel cancer pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 14912–14917 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snyder F. & Wood R. Alkyl and alk-1-enyl ethers of glycerol in lipids from normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cancer Res 29, 251–257 (1969). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert D.H. & Anderson C.E. Ether-linked glycerolipids in human brain tumors. Lipids 12, 188–192 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder F., Blank M.L. & Morris H.P. Occurrence and nature of O-alkyl and O-alk-I-enyl moieties of glycerol in lipids of Morris transplanted hepatomas and normal rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta 176, 502–510 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui W., Liu D., Gu W. & Chu B. Peroxisome-driven ether-linked phospholipids biosynthesis is essential for ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ 28, 2536–2551 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena M., Kalathur R.K.R., Neutzner M. & Christofori G. PyMT-1099, a versatile murine cell model for EMT in breast cancer. Sci Rep 8, 12123 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doll S. et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol 13, 91–98 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kagan V.E. et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 13, 81–90 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye X. et al. Distinct EMT programs control normal mammary stem cells and tumour-initiating cells. Nature 525, 256–260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantopoulos K., Porwal S.K., Tartakoff A. & Devireddy L. Mechanisms of mammalian iron homeostasis. Biochemistry 51, 5705–5724 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muckenthaler M.U., Rivella S., Hentze M.W. & Galy B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 168, 344–361 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller S. et al. CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis. Nat Chem 12, 929–938 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niwa M., Hirayama T., Okuda K. & Nagasawa H. A new class of high-contrast Fe(II) selective fluorescent probes based on spirocyclized scaffolds for visualization of intracellular labile iron delivered by transferrin. Org Biomol Chem 12, 6590–6597 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Houk R.S. Mass spectrometry of inductively coupled plasmas. Analytical Chemistry 58, 97A–105A (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Figueroa J.A., Stiner C.A., Radzyukevich T.L. & Heiny J.A. Metal ion transport quantified by ICP-MS in intact cells. Sci Rep 6, 20551 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoepken H.H., Korten T., Robinson S.R. & Dringen R. Iron accumulation, iron-mediated toxicity and altered levels of ferritin and transferrin receptor in cultured astrocytes during incubation with ferric ammonium citrate. J Neurochem 88, 1194–1202 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauckman K.A., Haller E., Flores I. & Nanjundan M. Iron modulates cell survival in a Ras- and MAPK-dependent manner in ovarian cells. Cell Death Dis 4, e592 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gammella E., Buratti P., Cairo G. & Recalcati S. The transferrin receptor: the cellular iron gate. Metallomics 9, 1367–1375 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Hajj M., Wicha M.S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S.J. & Clarke M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 3983–3988 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]