Abstract

Gene mutations that truncate the encoded protein can trigger the expression of related genes. The discovery of this compensatory response alters our thinking about genetic studies in humans and model organisms.

Conventional wisdom holds that modifying a gene to make the encoded protein inactive — ‘knocking out’ the gene — will have more severe effects than merely reducing the gene’s expression level. However, there are many cases in which the opposite occurs. In fact, the knockout of a gene sometimes has no discernible impact, whereas the reduction of expression (knockdown) of the same gene causes major defects1. Off-target or toxic effects of the reagents used for gene knockdown have sometimes been found to be the culprit2, but not always3, leaving one to wonder what else could be responsible. El-Brolosy et al.4 (page 193) and Ma et al.5 (page 259) provide an intriguing solution to this paradox.

The authors identify a molecular mechanism that activates the transcription of genes related to an inactivated gene, thereby compensating for the knockout. The existence of such a genetic compensation response was initially suggested by earlier studies, most notably the discovery3 that knockout of the egfl7 gene in zebrafish upregulates the expression of genes that encode proteins related to those encoded by egfl7. This upregulatory response was triggered only by mutation of egfl7, and not by egfl7 knockdown, thereby explaining why knockdown caused biological defects, whereas knockout largely did not. Similar observations have been made for other genes3,6, suggesting the existence of a general compensatory mechanism.

How does the compensatory mechanism work? By studying the effects of a variety of mutations in zebrafish embryos, both El-Brolosy et al. and Ma et al. found that the upregulation of compensatory genes is specifically triggered by mutations that generate short nucleotide sequences known as premature termination codons (PTCs). These sequences — also known as nonsense codons — signal the early cessation of the translation of messenger RNAs into proteins. Thus, an apt name for this upregulatory response is nonsense-induced transcriptional compensation (NITC).

The role of PTCs in NITC suggested the involvement of an RNA-degradation pathway called nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD), because NMD is also triggered by PTCs7. In support of this idea, El-Brolosy and colleagues observed that a protein called Upf1 — one of the main factors involved in NMD — is required for NITC. Further support came from Ma and co-workers’ discovery that PTCs that do not trigger NMD also failed to elicit NITC.

The two papers provide several lines of evidence suggesting that the agent that triggers NITC is the PTC-bearing mRNA generated from a mutant gene (Fig. 1). For example, both groups found that NITC is largely prevented when transcription of the mutant gene is compromised. As evidence that the PTC-bearing mRNA must be degraded by NMD to elicit NITC, El-Brolosy et al. found that injection of ‘uncapped’ mRNA, which is inherently unstable, into zebrafish embryos elicited NITC, whereas ‘capped’ (stable) mRNA did not.

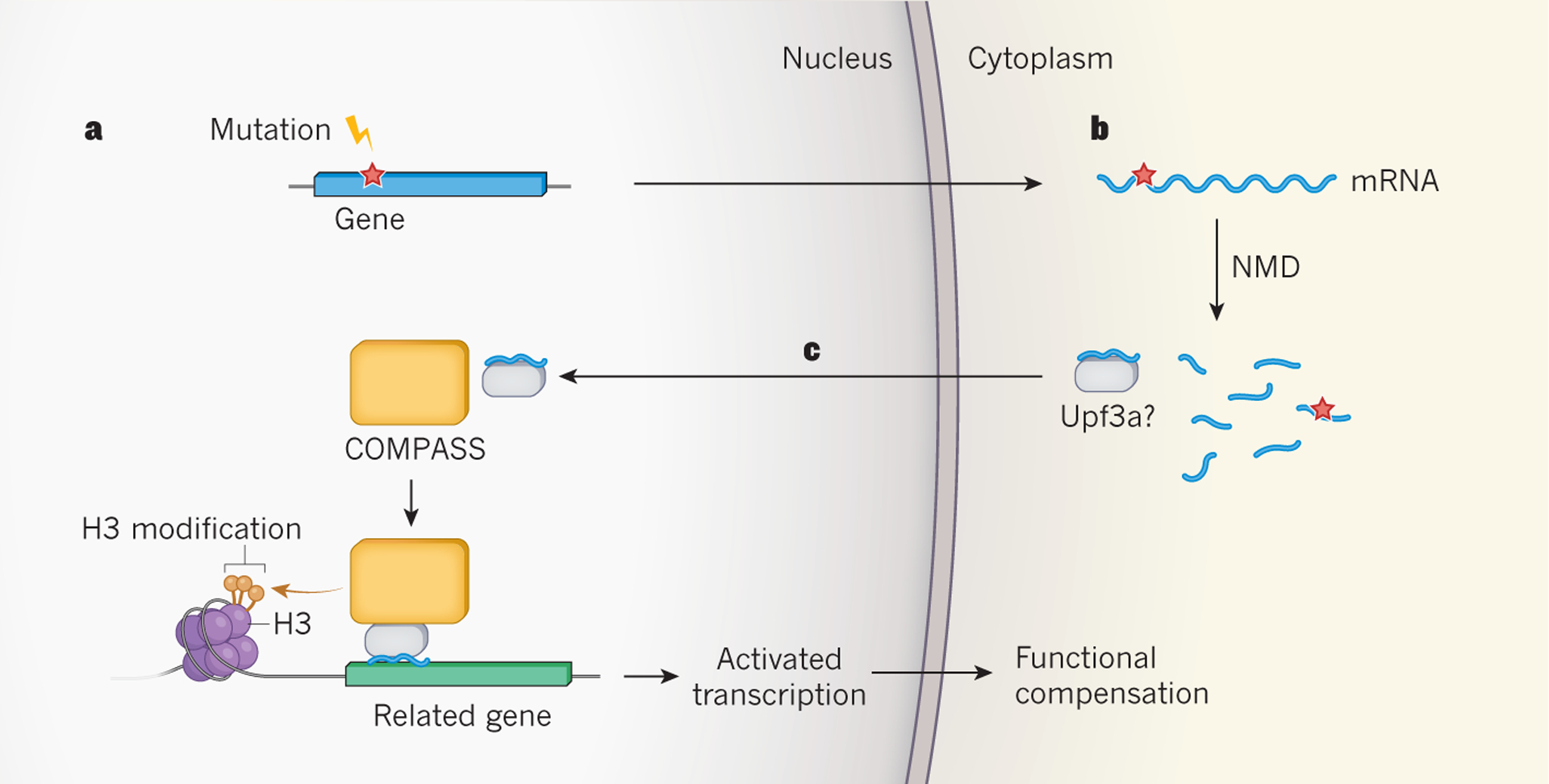

Figure 1 |. Proposed mechanism for mutation-induced biological compensation.

El-Brolosy et al.4 and Ma et al.5 report that mutations that lead to the production of truncated, often non-functional proteins indirectly activate the expression of related genes, to provide functional compensation. a, The mutations observed to trigger this process generate DNA sequences (red star) that lead to the production of messenger RNA molecules for which translation is prematurely terminated. b, These sequences also trigger mRNA degradation by a process called nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD), which both studies implicate in the compensatory response. c, El-Brolosy et al. propose that mRNA fragments generated by NMD bind selectively to complementary nucleotide sequences in related genes, and carry unknown regulatory factors to induce transcription. One of these factors might be Upf3a, an NMD factor that Ma et al. show is crucial for the transcriptional compensatory mechanism. They also find that Upf3a interacts with COMPASS — a protein complex that activates gene transcription by modifying one of the histone proteins (H3) with which genes are packaged in the nucleus. Both groups find that COMPASS is integral to the genetic compensatory response.

Both groups found that NITC is mediated by increased transcription of genes that are ancestrally related to the mutant gene. The increased transcription of these gene paralogues was accompanied by increased occupancy of the genes’ promoter regions by H3K4me3 — a transcription-inducing form8 of a DNA-binding protein called histone H3. The two groups went on to find that NITC depends on the COMPASS protein complex, which catalyses8 the formation of H3K4me3, thereby providing further evidence that this H3 modification has a role in the increased transcription of the gene paralogues.

How could a decaying mRNA specifically trigger transcriptional upregulation of genes similar to itself, but not of unrelated genes? On the basis of the finding that some factors required for the decay of RNA in the cytoplasm also ‘moonlight’ as transcriptional regulators in the nucleus9, El-Brolosy et al. posit a model in which cytoplasmic-RNA decay factors associated with PTC-bearing mRNA travel to the nucleus and recruit histone modifiers to activate the transcription of related genes. Specificity is provided by the RNA fragments generated by NMD, which bind to complementary nucleotide sequences in the gene paralogues (Fig. 1). This model also predicts that heterozygotic zebrafish, which have both a mutant and a wild-type copy of a gene, will upregulate the expression of the wild-type gene. Indeed, both research groups found that this is the case.

A key discrepancy between the two papers is that El-Brolosy et al. found that knockout of the upf1 gene prevented NITC, whereas Ma et al. observed that NITC was not impaired by knockdown of Upf1, nor by knockdown of the NMD factors Upf2 and Upf3b. It remains to be seen whether this apparent discrepancy results from the use of different approaches for perturbing Upf1, from introducing PTCs in different genes, or from other factors.

An intriguing discovery made by Ma et al. is that NITC requires the Upf3a protein, an enigmatic NMD factor that was previously shown10 to either repress or modestly promote NMD, depending on the mRNA targeted for degradation. The authors found that Upf3a interacts with several components of the COMPASS complex, and increases H3K4me3 occupancy at the promoter regions of upregulated paralogue genes. These findings led Ma et al. to propose that Upf3a recruits the COMPASS complex to gene-paralogue promoters to generate the H3K4me3 mark responsible for activating gene transcription.

The discovery of NITC will probably alter how genetic studies are interpreted and conducted in the future. For example, the unexpected finding that healthy humans typically have several loss-of-function mutations11 can now potentially be explained by compensation conferred by NITC. When constructing genetically engineered model organisms, it will be important to make mutants that do not trigger NITC, to avoid biological defects being masked. Indeed, NITC might explain why many knockouts produce few biological changes in mice, whereas chemical agents that block or activate the same targets have profound effects12,13.

El-Brolosy et al. demonstrated that NITC provides protective compensation not only in zebrafish embryos, but also in mouse cell lines. NITC’s reach might extend much further than this, given that gene knockouts in diverse organisms have been shown to produce less-severe defects than corresponding gene knockdowns1. How broadly does NITC act in a given organism? El-Brolosy et al. and Ma et al. together identified eight zebrafish genes and four mouse genes that, when mutated, trigger the NITC mechanism, but it remains unclear whether this is a property of most genes. It is also unknown what dictates NITC’s strength and specificity. Both research groups identified some specific mutant genes and mutations that trigger NITC only weakly, implying that there are factors yet to be understood that modulate NITC.

NITC adds to the arsenal of mechanisms that confer robustness on organisms in response to mutations. Indeed, NITC provides hope even when a gene has been completely inactivated by mutation. In the words of the writer Henry David Thoreau: “If we will be quiet and ready enough, we shall find compensation in every disappointment.”

References

- 1.El-Brolosy MA & Stainier DYR PLoS Genet. 13, e1006780 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kok FO et al. Dev. Cell 32, 97–108 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi A et al. Nature 524, 230–233 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Brolosy MA et al. Nature 568, 193–197 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Z et al. Nature 568, 259–263 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu P et al. J. Genet. Genom 44, 553–556 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popp MW-L & Maquat LE Annu. Rev. Genet 47, 139–165 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howe FS, Fischl H, Murray SC & Mellor J BioEssays 39, 1600095 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haimovich G et al. Cell 153, 1000–1011 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shum EY et al. Cell 165, 382–395 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacArthur DG et al. Science 335, 823–828 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks PC et al. Cell 79, 1157–1164 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bader BL, Rayburn H, Crowley D & Hynes RO Cell 95, 507–519 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]