Abstract

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of T cell activation, and metabolic fitness is fundamental for T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Insights into the metabolic plasticity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in patients could help identify approaches to improve their efficacy in treating cancer. Here, we investigated the spatiotemporal immunometabolic adaptation of CD19-targeted CAR T cells using clinical samples from CAR T cell-treated patients. Context-dependent immunometabolic adaptation of CAR T cells demonstrated the link between their metabolism, activation, differentiation, function, and local microenvironment. Specifically, compared to the peripheral blood, low lipid availability, high IL-15, and low TGFβ in the central nervous system microenvironment promoted immunometabolic adaptation of CAR T cells, including upregulation of a lipolytic signature and memory properties. Pharmacologic inhibition of lipolysis in cerebrospinal fluid led to decreased CAR T cell survival. Furthermore, manufacturing CAR T cells in cerebrospinal fluid enhanced their metabolic fitness and anti-leukemic activity. Overall, this study elucidates spatiotemporal immunometabolic rewiring of CAR T cells in patients and demonstrates that these adaptations can be exploited to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of CAR T cells.

Introduction

T cells dynamically reprogram their metabolic state during an immune response. This metabolic rewiring is necessary to support T cell activation, differentiation, and tissue adaptation, and metabolic fitness is fundamental for T cell antitumor activity. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CD19 CAR) T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL (1). In this therapy, patients’ T cells are genetically modified with recombinant receptors, which redirect the specificity, function, and metabolism of transduced T cells (2,3). In contrast to normal T cells, CAR T cells differ in several aspects. At first, to manufacture CAR T cells, ex vivo polyclonal T cells in leukapheresis products are activated using anti-CD3/CD28 beads, followed by lentiviral vector transduction that encodes the CAR, and continued expansion in cytokines such as IL-2 and IL-15 (4). Next, patients are preconditioned with lymphodepleting chemotherapy, establishing a favorable immune environment for adoptively transferred CAR T cells, improving their in vivo proliferation, persistence, and clinical activity (5). Lastly, post-infusion, CAR T cells traffic, expand, and exert anticancer activity systemically, independently of the major histocompatibility complex (6). Despite an increased understanding of CD19 CAR T cell biology based on CAR T cell products, little is known about CAR T cell metabolic reprogramming in patients (7).

Until recently, immunometabolism research was confined to bulk assays that captured an averaged steady metabolic state, precluding us from interrogating cellular metabolic heterogeneity and dynamics at the single cell level (8). Recent studies using mass cytometry (CyTOF) were able to interrogate the metabolic state of the heterogeneous and dynamic CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo, linking metabolic profile to cellular identity and allowing the direct analysis of the single cell from clinical samples ex vivo (9,10). In the present study, using patient-derived samples, we investigated how CD19 CAR T cells are metabolically adapted in multiple tissue compartments over the course of therapy and interrogated whether these adaptations can be used to enhance the antitumor efficacy of CAR T cell therapy in a preclinical model. We discovered context-dependent immunometabolic rewiring of CAR T cells, linking metabolic state, activation, differentiation, function, and tissue microenvironment. Specifically, compared to the peripheral blood, we found low lipid availability, high IL-15, and low TGFβ in the central nervous system microenvironment, promoting immunometabolic adaptation, including lipolytic signature and memory properties of CAR T cells. We show that pharmacological inhibition of lipolysis in cerebrospinal fluid leads to decreased survival of these cells, and CAR T cell metabolic fitness was recapitulated when manufactured in cerebrospinal fluid, which significantly enhanced anti-leukemic activity in a murine model for B-cell ALL.

Materials and Methods

Patients’ samples and CAR T cell therapy.

De-identified clinical samples were collected from a subset of adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), who received CD19-specific CAR-T cells in a phase 1/2 clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT02146924) (4). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of the City of Hope Internal Review Board (IRB #13447). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were labeled with clinical grade anti-CD14 and anti-CD25 microbeads, and CD14+ monocytes and CD25+ Tregs cells were depleted. Unlabeled negative fraction cells were labeled with cGMP grade biotinylated-DREG56 mAb followed by anti-biotin microbeads labeling. The CD62L+ T naïve/memory (Tn/mem) cells were purified with positive selection on CliniMACS™. The enriched CD62L+ Tn/mem cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads and underwent lentiviral transduction to express the CD19R(EQ)28ζ/EGFRt+ CAR, expanded in vitro in the presence of 50 U/mL rhIL-2 and 0.5 ng/mL rhIL-15 to achieve planned clinical cell dose and formulated for cryopreservation. Autologous CD19R(EQ)28ζ/EGFRt+ Tn/mem - enriched T Cells product was administered by intravenous infusion in a single dose on Day 0 following a 3-day lymphodepleting regimen.

Generation of CAR T cells in RPMI or CSF.

Patients’ enriched Tn/mem cells were stimulated with GMP Human T-expander CD3/CD28 Dynabeads™ (Dynal Biotech Cat#11141D) at a ratio of 1:3 (T cell:bead) overnight. Activated T cells were subsequently transduced with CD19R(EQ):CD28:ζ/EGFRt clinical construct at MOI=1 in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 5μg/ml protamine sulfate (Fresenius Kabi, 22905), 50U/mL rhIL-2 (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, NDC0078-0495-61), and 0.5 ng/mL rhIL-15 (CellGenix, 1013-050). Six days after stimulation, CD3/CD28 Dynabeads™ beads were removed using a DynaMag™-5 Magnet (Invitrogen, 12303D) and cells were plated at a concentration of 1x106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640/10% FBS or pooled human cerebrospinal fluid (Innovative Research, IRHUCSF1ML), 50U/mL rhIL-2, and 0.5 ng/mL rhIL-15, for 40 hours.

CAR T cells in vitro co-culture with target cell lines or LAL inhibitor.

On day one, patients’ samples were thawed and cultured in RPMI 1640/10% FBS, 50U/mL rhIL-2 (Novartis Pharmaceuticals, NDC0078-0495-61), and 0.5 ng/mL rhIL-15 (CellGenix, 1013-050) in the humidified incubator for overnight rest. On day two, CAR T cells were co-cultured at a concentration of 1x106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640/10% FBS in the incubator with human lymphoblastoid cells (LCL) 2:1 (CAR:tumor) ratio without supplemental cytokines, or irradiated (8000rads) 3T3-CD19 at 10:1 (CAR:tumor) ratio with 25U/mL rhIL-2, and 0.25 ng/mL rhIL-15, for 7 days. For LAL inhibitor experiments, on day two cells were cultured in pooled human cerebrospinal fluid (Innovative Research, IRHUCSF1ML) or RPMI 1640/10% FBS with 35pg/ml of IL-15 (equivalent to CSF level) with Lalistat (Tocris Bioscience, 6098) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a final concentration of 50 μM; DMSO was used as a control as indicated.

Mouse Xenograft Studies.

Immunocompromised NOD scid IL2Rgammanull mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the Animal Resource Center of City of Hope in accordance with the approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines (IACUC: 21034). 6-10-week-old NSG mice were injected intravenously with 1.0x10^6 Nalm6-ffluc+ leukemia cells. Nalm6 cells were obtained in 2017 from the ATCC and passaged twice a week up to 10 passages after thawing. Short tandem repeat cell line authentication is performed by ATCC prior to delivery. Mycoplasma testing was done regularly in house (last check on 7/2023) using the Myco alert Mycoplasma detection Kit (Lonza, LT07–318). Tumor burden was assessed before treatment and mice were randomized to groups to ensure equal tumor burden between treatment groups. Following tumor engraftment (four days after tumor infusion), PBS (untreated), mock (non-transduced T cells), and 5.0x105 CD19 CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF, were administered via intravenous tail injection. Tumor burden was monitored every seven days by live mice imaging using the LagoX optical imaging system (Spectral Instruments Imaging). For imaging, mice were injected i.p. with XenoLight D-luciferin potassium salt (Perkin Elmer, 122799). Images were analyzed using Aura Imaging Software (Spectral Instruments Imaging).

Metabolomics.

Plasma and CSF samples from matched patients were subjected to solvent-based metabolite extraction using 70% organic solvents (acetonitrile: methanol, 2:1, v/v) containing isotopically labeled internal standards (d8-Valine, 13C6-Phenyl alanine, 13C6 -adipic acid, d4-succinic acid) (11–13). Untargeted metabolomics was performed using an Ultimate 3000 BioRS coupled to an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) in HILIC LC-MS and RP LC-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes as described previously. The data were searched against HMDB, KEGG, and mzCloud databases using Compound Discoverer 3.2 (12). A pooled QC strategy was employed to determine compound selection for downstream analysis (11,13). The matrix effect between CSF and plasma was normalized using the area of the spiked internal standard with the lowest RSD. To compare healthy vs. patient CSF, data were acquired on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer using the same chromatographic and mass spectrometry parameters. Differentially abundant metabolites between CSF and plasma were determined using Student’s t-test. P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini Hochberg method (14). Only annotated metabolites were used for data representation. Pathway analysis was performed on Metaboanalyst 5.0 (15) using the SMPDB Homo sapiens library.

Metabolic analysis using the Seahorse XF96 extracellular flux analyzer.

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured using the Seahorse Bioscience XF96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Agilent). Briefly, 0.1 million cells per well (minimum of three wells per sample) were seeded in Seahorse XFe96 PDL cell culture microplates on the day of the experiment. Cells were suspended in Seahorse XF RPMI medium (200ul/well, Agilent, 103576-100) supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. OCR was measured following sequential injections of 2.5 μM oligomycin A, 2.5 μM BAM15, and 0.5 μM rotenone/antimycin A (all Agilent, 103772-100) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cytokine Analysis.

Cytokine multiplex analysis:

samples were analyzed for 30 cytokines using “Human Cytokine Thirty-Plex Antibody Magnetic Bead Kit” (Invitrogen, LHC6003M) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, Invitrogen’s multiplex bead solutions were vortexed for 30 seconds and 25ul was added to each well and washed twice with Wash Buffer. The samples were diluted 1:2 with Assay Diluent and loaded onto Greiner flat-bottom 96 well microplate; 50ul of Incubation Buffer had been added previously to each well. Cytokines standards were reconstituted with Assay Diluent, then Serial dilutions of cytokine standards were prepared in parallel and added to the plate. Samples were incubated on a plate shaker at 500 rpm in the dark at room temperature for 2 hours. The plate was applied to a magnetic device designed to accommodate a microplate and washed three times with 200ul of Wash Buffer. 100ul of biotinylated Detector Antibody was added to each well. The plate was incubated on a plate shaker for 1 hour. After washing three times with 200ul of Wash Buffer, Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (100ul) was added to each well. The plate was incubated on a plate shaker for 30 min and then was washed three times, and each well was resuspended in 150ul wash buffer and shaken for 1 min. The assay plate was transferred to the Flexmap 3D luminex system (Luminex corp.) for analysis, Cytokine concentrations were calculated using Bio-Plex Manager 6.2 software with a five parameter curve-fitting algorithm applied for standard curve calculations for duplicate samples.

TGFβ 1, 2, and 3 analysis:

samples were analyzed for TGFβ 1, 2, and 3 using the TGF-b Premixed Kit (R&D Systems, FCSTM17-03). All samples required a pretreatment step to convert the latent proteins into their immunoreactive state prior to detection. Activation was accomplished by adding 20 μl of 1N HCl to 100 μl of sample and incubation for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by neutralization with 20 μl of 1.2N NaOH/0.5M HEPES. Briefly, as per manufacturer’s instructions, TGFβ standards were reconstituted with the calibrator diluent and serial dilutions were prepared, Samples were also diluted 15-fold in calibrator diluent and 50 μl of both standards and samples were added to Greiner flat-bottom 96 well microplates in duplicate. Fifty 50 μl of bead solution was then added into each designated well, followed by incubation on a plate shaker at 500 rpm in the dark at room temperature for 2 hours. The plate was then applied to a magnetic plate holder and washed three times with 100 μl of Wash Buffer. Fifty μl of biotinylated detection antibody solution was added to each well, and the plate was incubated on a plate shaker for 1 hour. After washing three times with 100 μl of wash buffer, streptavidin-phycoerythrin was added to each well, and plate was incubated on a plate shaker for an additional 30 minutes before being washed three times. Finally, the contents of each well were resuspended in 100 μl of wash buffer, shaken for 1 minute and the plate was transferred to the Flexmap 3D Luminex system (Luminex corp.) for analysis, TGFβ concentrations were calculated using Bio-Plex Manager 6.2 software with a five parameter curve-fitting algorithm applied for standard curve calculations for duplicate samples.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry.

For surface staining, cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to CD3 (BD Bioscience, 563109, 347347), CD4 (BD Bioscience, 347324), CD8 (BD Biosciences, 348793), EGFR (Biolegend, 352906, 352910), CD45RA (BD Biosciences, 550855), CCR7 (Biolegend, 353203), CD19 (Life Technologies, MHCD1905), CD45RO (BD Biosciences, 555492), CD69 (BD Biosciences, 340548). Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer, which consists of HBSS (Gibco, 14175095), 2% FBS and NaN3 (Sigma, S8032), and incubated with antibodies at 4°C in the dark. For mitochondrial mass staining, cells were stained with MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen, M7514) at 200 nM as per the manufacturer’s protocol in addition to the surface antibody cocktail. For cell proliferation by dye dilution, cells were stained with CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen, C34557) at 1 μM as per the manufacturer’s protocol. For neutral lipids staining, cells were stained with Bodipy 500/510 (Invitrogen, D3823) at 2μM as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Following a washing step with FACS buffer, DAPI (Invitrogen, D21490) or Fixable Viability Dye (Invitrogen, 65-0866-18) was added for viability staining before analysis. Flow cytometry was performed using MASCQuant Analyzer 10 (Miltenyi Biotech, 130-096-343), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

CyTOF.

Metal-isotope conjugated monoclonal antibodies (Table SX-Full Panel w/ details) targeting T cell phenotypic, activation, and metabolic proteins were used to evaluate the metabolic and activation properties of patient-derived CAR T cells in vitro and ex vivo. Non-commercially available metal-tagged antibodies were generated by conjugating each purified antibody to its respective metal isotope following standard procedures (Maxpar Antibody Labeling User Guide PRD002). Samples were stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Maxpar® Phospho-Protein Staining PRD016, or Maxpar® Cytoplasmic/Secreted Antigen Staining PRD017) and acquired on a Helios mass cytometer (Standard Biotools).

CyTOF data were analyzed using OMIQ software from Dotmatics (www.omiq.ai), GraphPad Prism 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com), and R (version 4.1.2). CyTOF fcs files were time-normalized using EQ Four Element Calibration Beads (Standard Biotools, 201078) according to manufacturer’s instructions, using bead passport EQ-P13H2302_ver2 and manually filtered to remove beads, doublets, debris, and dead cells using standard Gaussian parameter exclusion method. All CyTOF features were arcsinh transformed with a cofactor of 5 and CAR T cells were identified by manual gating for the expression of both CD3 and EGFR, using patient’s leukapheresis product to set the CAR+ gate. All UMAP projections were calculated using the standard settings in OMIQ, namely 15 neighbors, a minimum distance of 0.4, 2 components, Euclidean metric, and a random seed. All clustering was performed using the FlowSOM integration in OMIQ with 100 nodes, Manhattan distance metric, and 4 metaclusters. All heatmaps are normalized using z-score normalization in R. Ex vivo data were batch corrected using the CyCombine package in R (16). The R packages used for this analysis are: cycombine, ggplot2, ggcorrplot, scales, Hmisc, viridis, tidyverse, qgraph, and plyr.

Visualization.

Schematic representations were created with BioRender.com. Figures were prepared in Illustrator (Adobe).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical tests used in this study are described in detail in the corresponding figure legends. For comparisons of cell populations derived from the same individual across two groups, we performed matched t-tests. For comparisons between multiple groups, we performed 2-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to account for multiple hypotheses testing.

Data availability.

The metabolomics data generated in this study are available in the Supplementary files. All other datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

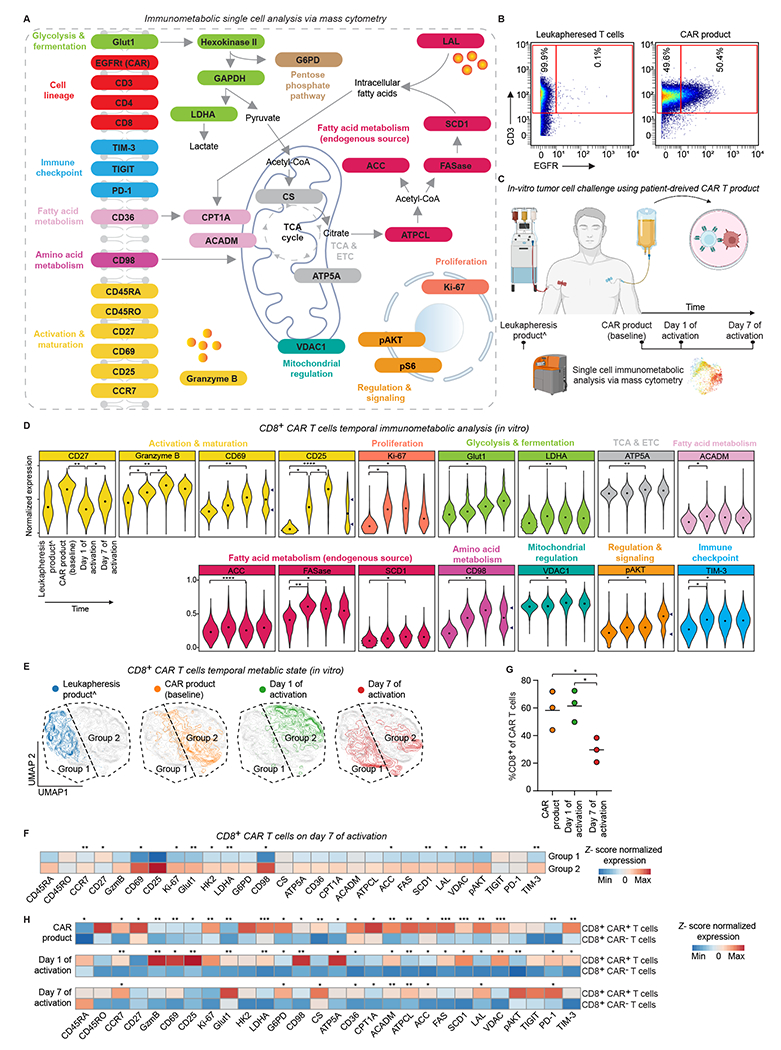

We leveraged the highly multiplexed capacity and single-cell resolution of mass cytometry to interrogate the immunometabolic landscape of CD19 CAR T cell therapy in clinical samples from 19 patients with ALL who were treated with CD19-28ζ CAR T cells at City of Hope National Medical Center (4) (Supplementary Table 1). To this end, we developed an integrative panel with antibodies specific for CAR, cell lineage, metabolic, activation, maturation, proliferation, cell signaling/regulation, and immune checkpoint proteins (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Table 2). Key metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, fermentation, pentose phosphate, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), the electron transfer chain (ETC), and both amino and fatty acid metabolism were assessed by measuring key metabolite transporters and metabolic enzymes, which have been shown to correlate with glycolytic and respiratory activity (9,10,17). CAR T cells were identified using a metal-conjugated antibody specific for truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor (huEGFRt) as this marker is co-expressed in our CD19 CAR T construct (18), offering us a unique tracking and gating tool. Patients’ matched leukapheresis product (non-CAR T cells) was used as negative control (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Immune activation of CAR T cells induces metabolic rewiring.

A. Panel schematic of the immunological proteins and metabolic pathways interrogated by mass cytometry.

B. Gating strategy of CAR and non-CAR T cells based on CD3 and EGFR expression in mass cytometry.

C. Experimental workflow to interrogate temporal immunometabolic changes using patient derived leukapheresis and CAR T cell products.

D. Normalized (99.9th percentile) expression of statistically significant proteins across CD8+ CAR T cells. The median metal intensity (MMI) for each protein in each timepoint is represented by black dots. Bimodality indicated by arrows. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 3 patients.

E. Temporal metabolic state UMAP of CD8+ CAR T cells considering only the expression of metabolic proteins. Each color represents cells from different time point. Dashed lines represent manually assigned groups based on cell distribution in leukapheresis product; n = 3 patients.

F. Heat map indicating z-score normalized median expression of all CyTOF markers assessed across manually assigned groups 1 and 2 on day 7 of activation. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups; n = 3 patients.

G. Longitudinal frequencies of CD8+ CAR T cells; n = 3 patients.

H. Heat map indicating z-score normalized median expression of all CyTOF markers assessed longitudinally across manually assigned CAR+ and CAR− CD8 T cells. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups; n = 3 patients.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. ^Non-CAR T cells (Tn/mem CD8+ cells). Panels A and C were created with biorender.com.

Glut1: Glucose transporter 1; HK2: Hexokinase 2; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LDHA: Lactate dehydrogenase A; G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; CS: Citrate synthase; ATP5a: ATP synthase; CPT1A: carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A; ACADM: Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase medium chain; ATPCL: ATP- citrate lyase; ACC: Acetyl CoA carboxylase; FASN: Fatty acid synthase; SCD1: Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; LAL: Lysosomal acid lipase; VDAC1: Voltage-dependent ion channel 1; TCA: Tricarboxylic acid cycle; ETC: Electron transport chain.

Immune activation of CAR T cells induces metabolic rewiring.

Immune activation of T cells is associated with an increased metabolic demand (19). To study the temporal metabolic remodeling of CAR T cells and its relation to cell activation, function, and proliferation, we analyzed CD8+ CAR T cells from patients’ leukapheresis products (Tn/mem cells, non-CAR T), CAR products, and CAR products co-cultured with a CD19+ lymphoblastoid cell line sampled on day 1 and day 7 of activation (Fig. 1C). To mimic the decline in IL-2 and IL-15 levels seen in patients’ post-infusion (Supplementary Fig. 2A), we stopped supplementing the cells with supporting cytokines upon incubation with tumor cells.

The temporal protein expression pattern revealed increased expression in metabolic, activation, proliferation, signaling and regulation proteins in CAR T cells compared to non-activated CD8+ Tn/mem cells from leukapheresis products (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 3A). Specifically, activation markers CD25 and CD69, cytotoxic mediator granzyme B, proliferation marker Ki-67, glycolytic enzymes (Glut1, LDHA), ETC enzyme (ATP5A), fatty acid synthesis enzymes (ACC, FASase, SCD1), amino acid transporter CD98 together with immune checkpoint TIM-3, and cell regulatory proteins (VDAC1, pAKT) were significantly overexpressed on day 1 of activation compared to leukapheresis products, suggesting these cells utilize multiple metabolic pathways to support their extensive bioenergetic demands.

To further interrogate the temporal metabolic remodeling of CAR T cells upon engagement with different activation drivers in vitro (e.g., TCR engagement via anti-CD3/CD28 beads in CAR T cell production, CAR activation via CD19+ tumor cell engagement, and activation via IL-2 and IL-15 cytokines), we visualized these single-cell data via dimensionality reduction (UMAP) considering only the expression of the metabolic proteins (Glut 1, HK2, GAPDH, LDHA, G6PD, CD98, CS, ATP5A, CD26, CPT1A, ACADM, ATPCL, ACC, FASase, SCD1, LAL, VDAC1, pAKT) (Fig. 1E). This analysis showed that CD8+ CAR T cells acquire distinct metabolic states driven by different activation mechanisms encountered in vitro. Intriguingly, on day 7 of activation, CAR T cells polarized into two groups: group 1, which was in closer proximity to leukapheresis products, and group 2, which was in closer proximity to day 1 of activation (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. 4A). Sub-analysis of the expression profile of the two groups demonstrated group 2 to be enriched in activation, proliferation, and metabolic markers. In contrast, group 1 had a more quiescent activation and metabolic profile resembling the non-activated leukapheresis products (Fig. 1F), suggesting an immunological contraction phase of CD8+ CAR T cells following tumor clearance and cytokine subsidence (20–22). Further supporting our immunological contraction hypothesis, day 7 CD8+ CAR T cells demonstrated decreased abundance compared to CAR product and day 1 of activation (Fig. 1G).

Lastly, we sought to study the temporal immunometabolic differences between CAR-negative and CAR-positive CD8 T cells sharing identical conditions by gating on CD3+ EGFR− and CD3+ EGFR+ cells, respectively (Fig. 1H). In CAR products, compared to CAR-negative cells, CAR-positive cells revealed significant upregulation in memory markers (CCR7, CD27), decreased expression in activation markers (Granzyme B, CD25, CD69), increased expression of proliferation marker Ki-67, and upregulation of all fatty acid metabolic proteins. On day one post-activation, CAR-positive cells showed a significant shift toward activation, proliferation, and effector-like phenotype following CAR-specific activation. Including upregulation of cytotoxic and activation proteins (Granzyme B, CD25, CD69), glucose and amino-acid transporters (Glut1 and CD98), ETC enzyme (ATP5A), cell regulatory proteins (VDAC1, pAKT), and maintained upregulation of most fatty acid proteins, similar to the metabolic state described in early activated T cells (10). On day 7 post-activation, following CAR-specific antigen clearance and the decline in IL-2 and IL-15 cytokines, CAR-positive cells, compared to CAR-negative cells, did not exhibit significant expression of activation and proliferation markers yet maintained significantly higher expression of memory marker CCR7 and the majority of fatty acid markers, suggestive of a post contraction memory-like phenotype. Together, these analyses demonstrate the metabolic rewiring of CAR T cells upon immune activation in vitro.

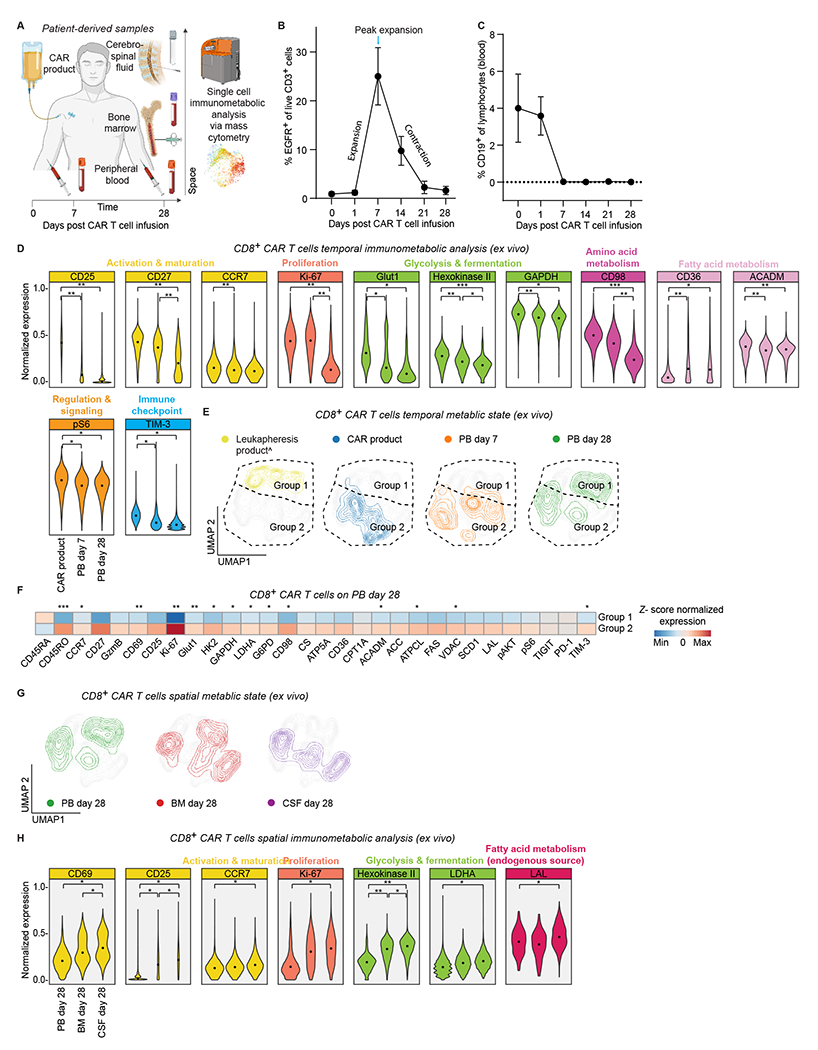

Patients’ CAR T cells reveal spatiotemporal metabolic adaptation.

In addition to the mode of immune activation, the metabolic state of T cells is influenced by the tissue in which they function and reside (23). To investigate the spatiotemporal metabolic influences on CD8+ CAR T cells in vivo, we analyzed clinical samples from patients utilizing our highly multiplexed immunometabolic CyTOF panel, complete with our EGFR-based CAR T cell detection method. For each patient, we analyzed the CAR product, peripheral blood (PB) on day 7, and peripheral blood, bone marrow (BM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on day 28 post-CAR T cell infusion (Fig. 2A). In our study cohort, CAR T cell expansion peaked on day 7 (Fig. 2B), which coincided with CD19+ B cell clearance in the peripheral blood (Fig. 2C). Response assessment on day 28 showed that all patients achieved B cell aplasia in the peripheral blood, complete remission in the bone marrow, and leukemic cells were undetected in the central nervous system (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Patients’ CAR T cells reveal spatiotemporal metabolic adaptation.

A. Experimental workflow to interrogate spatiotemporal immuno-metabolic changes using patient derived samples of CAR T cell product, peripheral blood (days 7 and 28), bone marrow and cerebrospinal fluid (day 28).

B. Persistence of CAR T cells in patients’ blood after CAR T cell infusion on days 0, 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. The percentage of EGFR+ T cells are gated from live CD3+ cells via flow cytometry; n = 6 patients.

C. Levels of CD19+ cells in blood circulation after CAR T-cell infusion. CD19+ cells are gated from live cells using flow cytometry; n = 6 patients.

D. Normalized (99.9th percentile) expression of statistically significant proteins across CD8+ CAR T cells. The MMI for each protein in each timepoint is represented by black dots. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 6 patients.

E. Temporal metabolic state UMAP of CD8+ CAR T cells considering only the expression of metabolic proteins. Each color represents cells from different time point. Dashed lines represent manually assigned groups based on cell distribution in leukapheresis product; n = 6 patients.

F. Heat map indicating z-score normalized median expression of all CyTOF markers assessed across manually assigned groups 1 and 2 on peripheral blood day 28. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups; n = 6 patients.

G. Spatial metabolic state UMAP of CD8+ CAR T cells considering only the expression of metabolic proteins. Each color represents cells from different time point; n = 6 patients.

H. Normalized (99.9th percentile) expression of statistically significant proteins across CD8+ CAR T cells. The MMI for each protein in each tissue is represented by black dots. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 6 patients.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. ^Non-CAR T cells (Tn/mem CD8+ cells). Panel A was created with biorender.com.

Longitudinally, CAR T cells in PB on days 7 and 28 had lower expression of activation, memory, proliferation, and metabolic enzymes and transporters than CAR product on day 0, possibly reflecting the contraction after activation (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. 3B). Notably, activation marker CD25, memory marker CD27, proliferation marker Ki-67, glycolytic enzymes (Glut1, HK2, GADPH), amino acid transporter CD98, fatty acids oxidation and synthesis enzymes (ACADM, FASase), together with immune checkpoint TIM-3, and the mTOR target ribosomal protein S6 (pS6) were significantly lower in the PB both on day 7 and day 28 compared to the CAR product. Additionally, memory marker CCR7 was significantly lower in the PB on day 7 compared to the CAR product (Fig. 2D). However, we also observed that fatty acid transporter CD36 was significantly higher on day 7 and day 28 compared to the CAR product (Fig. 2D).

Next, to further investigate the temporal immunometabolic changes, we visualized these high dimensional single-cell metabolic data via UMAP based exclusively on their metabolic proteins and revealed distinct metabolic state over time (Fig. 2E). Similar to our in vitro findings, day 28 PB CD8+ CAR T cells polarized into two groups post tumor engagement and immunological contraction (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Fig. 4B). Group 1 situated closer to leukapheresis products had a more quiescent activation and metabolic profile, while group 2, located in closer proximity to activated CAR T cells was enriched in activation, proliferation, and metabolic markers (Fig. 2F). In summary, the temporal analysis of CAR T cells in the peripheral blood compartment suggested the interplay between CAR T cell activation via tumor engagement and subsequent clearance, cytokine dynamics, and the cellular metabolic state of CAR T cells in vivo over time.

Spatially, metabolic analysis at the same time point of the PB, BM, and CSF on day 28 revealed distinct metabolic state over space (Fig. 2G and Supplementary Fig. 4C). We found greater expression of activation, proliferation, and metabolic markers in the CSF, and to a lesser extent in the BM, compared to the relative resting state of CAR T cells in the PB (Fig. 2H and Supplementary Fig. 3B). While CAR T activation in day 28 BM could potentially be induced by reconstituting CD19+ B cells, PB and CSF evaluation by flow cytometry revealed a lack of CD19+ cells, suggesting that the CSF niche triggers higher metabolism and proliferation of CAR T cells by another means than engagement with CD19+ tumor cells. Compared to the PB, CSF CAR T cells were significantly enriched with memory marker CCR7, activation marker CD25, activation and tissue-resident memory marker CD69, proliferation marker Ki-67, rate limiting glycolytic enzyme HK2, fermentative glycolysis enzyme LDHA, and lipolytic enzyme lysosomal acid lipase (LAL). Additionally, CAR T cells in the CSF had a low level of the cytotoxic mediator granzyme B, a high level of the memory marker CD27, and a high level of the oxidative phosphorylation enzyme ATP5A (Supplementary Fig. 3B), exhibiting many established features of memory CD8+ T cells (9,21,24–26). Overall, our analysis revealed context-dependent metabolic adaptation of CAR T cells with distinct spatiotemporal metabolic states, emphasizing the highly dynamic nature of CD8+ CAR T cells over time and space.

Intended by our unique Tn/mem manufacturing platform, we quantified the fraction of non-Tn/mem CAR T cells in patients’ products and analyzed their overall phenotype. Non-Tn/mem CAR T cells were less than 10% of total CD8+ CAR T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5A), and consistent with their more differentiated effector phenotype and limited proliferative capacity (27) exhibited quiescent activation and metabolic profile compared to Tn/mem CAR T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5B).

LAL-mediated lipolysis supports CAR T cell survival in the low lipid and high IL-15 microenvironment found in the CSF.

The metabolic state of T cells is also influenced by the local microenvironment in the tissue of residence (23). Intrigued by the metabolic differences between day 28 PB and CSF, we sought to investigate these local microenvironments further. To study the metabolite content of the two compartments, we performed an untargeted, broad metabolomics analysis using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry on patients’ matched CSF and PB samples on day 28 post-infusion. We identified 851 differentially abundant metabolites (p < 0.05) between matched CSF and PB samples (Fig. 3A). Of these, 820 metabolites passed FDR (q < 0.05), where 113 metabolites were more abundant, and 707 metabolites were less abundant in the CSF compared to blood, highlighting the nutrient scarcity in the CSF (Supplementary Table 3). Compared to plasma, CSF samples were lower in glucose, lactate, medium to long-chain fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and the majority of both glucogenic and ketogenic amino acids, yet higher in TCA and oxidative phosphorylation metabolites (succinic acid, α-keto glutaric acid, NAD+, and NADH), (Supplementary Table 3). Analysis of the top 10 differentially abundant metabolites revealed 9 of the top 10 less abundant metabolites in CSF to be lipids. In comparison, 3 out of the top 10 more abundant metabolites in CSF were related to TCA and oxidative phosphorylation (citric acid, succinyl-adenosine, phosphor-pantothenic acid) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. LAL-mediated lipolysis supports CAR T cell survival in the low lipid and high IL-15 microenvironment found in the CSF.

A. Unsupervised clustering of significantly different metabolites between patients’ CSF and PB on day 28 post infusion; n = 8 patients. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed t-test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

B. Volcano plot showing differentially abundant metabolites between patients’ CSF and PB on day 28 post infusion. The vertical lines represent a ± 1.5-fold change, and the horizontal line shows adjusted p = 0.05 on a Log10 p-value scale; n = 8 patients.

C. IL-5, -12, and -15 concentrations (pg ml−1) of pre-lymphodepletion CSF, and day 28 serum and CSF. Bars show mean values. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 8 patients.

D. Experimental workflow to interrogate the effect of LAL-mediated lipolysis on patients’ CAR T cells survival in the lipid-deprived CNS microenvironment.

E. Ratio of CD8+ CAR T cells relative to the number of cells plated at time0 following treatment with the LAL inhibitor Lalistat or vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide). A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 4 patients.

F. Ratio of CD8+ CAR T cells relative to the number of cells plated at time0 following incubation in RPMI with CSF level of IL-15 and treatment with the LAL inhibitor Lalistat or vehicle. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 4 patients.

G. Mean MFI of Bodipy staining for neutral lipids in CD8+ CAR T cells. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 4 patients.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. Panel D was created with biorender.com.

To further interrogate the microenvironmental differences between the PB and CSF, we analyzed cytokines related to T cell activation, differentiation, proliferation, and metabolism (28,29). Our analysis of paired samples on day 28 revealed decreased levels of the pro-effector cytokines IL-5 and IL-12 (30,31) and increased levels of IL-15, which is essential for the homeostatic proliferation and survival of memory CD8+ T cells (29) in the CSF compared to the PB (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 2B). We then asked whether these cytokines levels in the CSF were related to CAR T cell therapy. To this end, we examined IL-5, -12, and -15 cytokine levels in the CSF pre-lymphodepletion. We revealed significantly elevated levels of IL-15 compared to PB day 28 (Fig. 3C), suggesting that high levels of IL-15 are an intrinsic property of the CNS in our cohort. Interestingly, supporting our findings of an enhanced memory phenotype and LAL expression in CSF CAR T cells, it has been shown that IL-15-induced memory T cells use LAL-mediated cell-intrinsic lipolysis to mobilize fatty acids for oxidative phosphorylation and memory T cell survival and development (32).

Next, we wondered whether LAL-mediated lipolysis plays a role in CD8+ CAR T cells survival in the lipid-deprived CNS microenvironment. To this end, we first compared CSF from pooled donors to CSF from our patient cohort. We found similar metabolomic profiles and IL-15 levels between the two groups (Supplementary Figure 6A–B), including a total of 796 non-redundant metabolites (6287 compounds) with only 15 statistically significant different (q < 0.05) metabolites (Supplementary Table 4A and 4C), confirming the potential use of pooled donor-derived CSF to mimic the in-vivo CNS microenvironment. Of these 15 metabolites, 13 metabolites (4 lipids, 4 organic acids, 1 dipeptide, glucose, and its metabolite) were higher, whereas two metabolites (linoleic acid and PE-NMe2(18:1/18:1) were lower in patients compared to healthy individuals. These 15 significantly different metabolites were mapped to 16 pathways (Supplementary Table 4B) where fatty acid biosynthesis, pyruvate metabolism, and paraldehyde degradation were significantly (p<0.05) enriched. Next, we cultured CAR T cell products from our patient cohort in pooled donor-derived CSF without supplemental cytokines for 72 hours with and without Lalistat, a selective LAL pharmacological inhibitor (33) (Fig. 3D). We found that CD8+ CAR T cells treated with the LAL inhibitor had significantly decreased survival compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3E). While CAR T cells cultured in standard media supplemented with CSF level of IL-15 (35 pg/ml) with or without LAL inhibitor persisted, excluding the possibility that culturing cells for 72 hours with low cytokines alone led to our findings and suggesting a specific role for LAL in CSF microenvironment (Fig. 3F). Moreover, consistent with decreased lipolysis, LAL inhibited CAR T cells exhibited a significantly higher level of neutral lipid (Fig. 3G). Altogether, these data further support that CD8+ CAR T cells can upregulate LAL-mediated lipolysis to support their survival in the lipid-poor environment of the CNS.

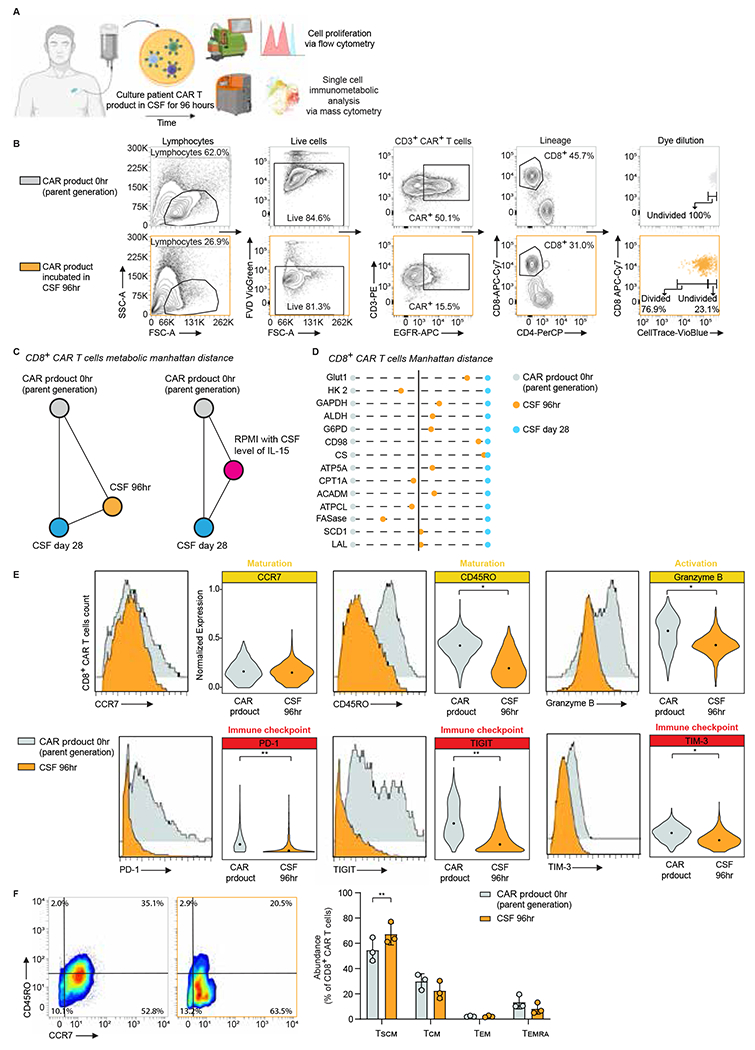

The CSF immuno-metabolically rewires CAR T cells.

To better understand the immunometabolic rewiring effects on CAR T cells due to the microenvironment found in the CNS, we incubated patients’ CAR T cell products in healthy donor-derived CSF without supplemental cytokines for 96 hours and interrogated their proliferative and immunometabolic profile (Fig. 4A). The overall percentage of CAR T cells cultured in CSF at 96 hours was decreased compared to the starting products (Fig. 4B, CD3+ vs. CAR+ flow plot); however, dye-dilution assay revealed that the remaining CD8+ CAR T cells could divide in the nutrient-poor CSF (34), suggestive of a metabolic selection of functional CAR T cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. The CSF immuno-metabolically rewires CAR T cells.

A. Experimental workflow to interrogate the effect of CNS microenvironment on patients’ CAR T cell products.

B. Representative data of gating strategy and cell proliferation measured by CellTrace dye via flow cytometry.

C. Manhattan distance between patients’ product, day 28 CSF, and product incubated in CSF for 96 hours or RPMI with CSF level of IL-15 (CD8+ CAR T cells), considering only the expression of metabolic proteins.

D. Manhattan distance between patients’ product, day 28 CSF and product incubated in CSF for 96 hours, based on the MMI of each metabolic CyTOF marker in CD8+ CAR T cells; n = 3 patients.

E. Histograms and violin plots of phenotypic and functional markers of CD8+ CAR T cells in patients’ product and product incubated in CSF for 96 hours. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 3 patients.

F. Representative mass cytometry density plots showing expression of CD45RO and CCR7 and abundance of canonical T cell subsets in CD8+ CAR T from patients’ product and product incubated in CSF for 96 hours. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 3 patients. Data are shown as mean ± s.d.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Panel A was created with biorender.com.

TCM: central memory; TEM: effector memory; TEMRA: terminally differentiated effector memory expressing CD45RA; TSCM: stem cell memory.

Furthermore, to evaluate the metabolic rewiring of the CSF-cultured CAR T cells, we calculated the pairwise Manhattan distances between patients’ CAR product, CSF day 28, and CAR T product incubated in CSF at 96 hours, considering only the expression of the metabolic proteins (Glut 1, HK2, GAPDH, LDHA, G6PD, CD98, CS, ATP5A, CD26, CPT1A, ACADM, ATPCL, ACC, FASase, SCD1, LAL). The expression levels of the metabolic proteins assessed by our panel were compared in CD8+ CAR T cells across each condition. Overall, CAR products incubated in CSF acquired a metabolic state which is more similar to day 28 CSF than CAR product alone (Fig. 4C), while CAR T cells cultured in standard media supplemented with the CSF-equivalent level of IL-15 (35 pg/ml) did not show the same rewiring towards day 28 CSF, excluding the possibility that culturing cells for 96 hours with low cytokines led to our findings and suggesting that IL-15 alone is not solely responsible for the metabolic rewiring seen in the CSF (Fig. 4C). Specifically, the expression levels of the majority of the metabolic proteins in CSF 96 hours, including Glut1, GAPDH, LDHA, G6PD, CD98, CS, ATP5A, ACADM, SCD1, and LAL were more similar to the expression levels in CSF day 28 (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, CAR T products incubated in CSF also adopted a memory phenotype resembling day 28 CSF samples and when compared with CAR T products exhibited lower expression of effector granzyme B, inhibitory receptors PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3 (Fig. 4E), and higher frequency of a less-differentiated stem cell-like memory phenotype (Fig. 4F). These findings recapitulate our clinical data that infused CD8+ CAR T cells undergo immunometabolic adaptation, proliferate, and acquire a memory phenotype induced by the CNS microenvironment.

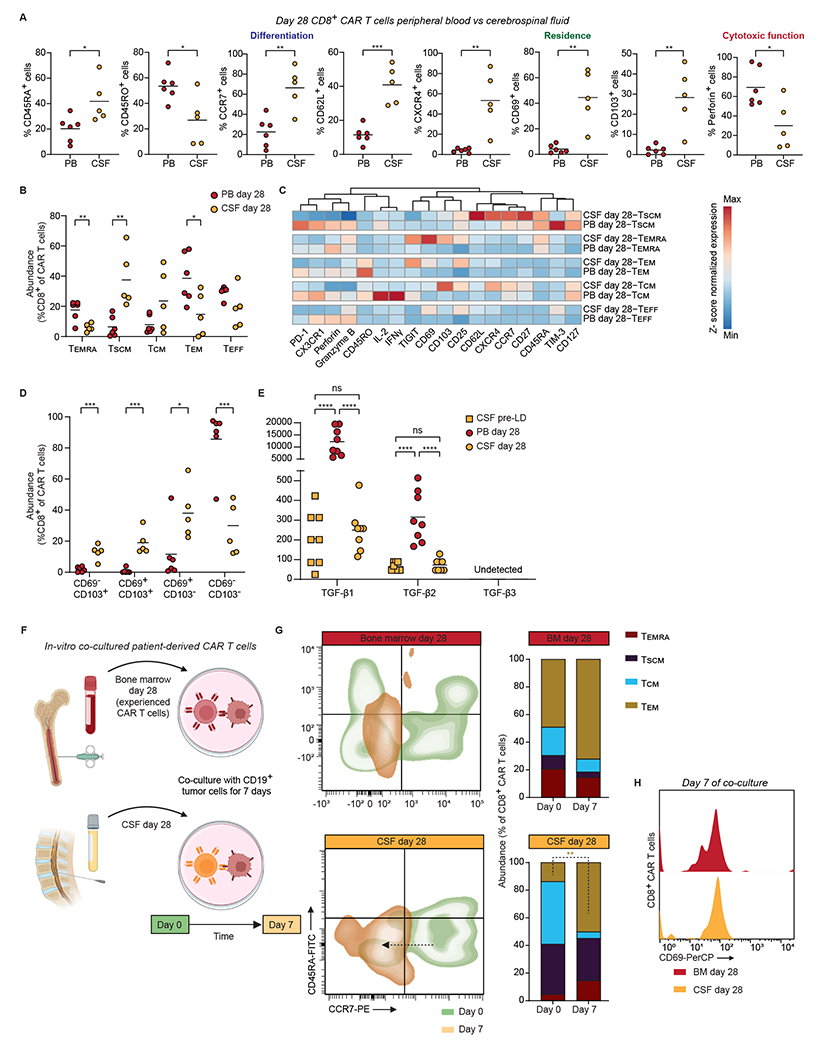

CSF-resident CAR T cells exhibit improved memory characteristics.

To further expand our understanding of the memory characteristics of CSF CAR T cells, we developed a memory-phenotyping CyTOF panel to perform phenotypic analysis of CD8+ CAR T cells in day 28 PB and CSF clinical samples from our cohort (Supplementary Table 5). Compared to the PB, CSF CAR T cells expressed significantly higher levels of CD45RA and memory residence markers CCR7, CD62L, CXCR4, CD69, CD103, and significantly lower levels of CD45RO and the cytotoxic mediator perforin (Fig. 5A). Intrigued by the memory signature of CSF CAR T cells, we first analyzed the abundance of the canonical T cell subsets in both compartments. CSF CAR T cells were significantly dominated by stem-cell memory (SCM)-like cells, while PB CAR T cells were significantly dominated by effector-memory and effector memory RA positive (EMRA)-like cells (Fig. 5B). Further characterization of the SCM-like subset revealed that CAR T cells in the CSF were CD127high, CD27high, CXCR4high, C62Lhigh, TIM-3low, PD-1−, TIGITlow, typical of long-lived memory cells and associated with an enhanced recall response (35), while CAR T cells in the PB expressed elevated exhaustion markers PD-1 and TIM-3, and effector markers granzyme B, perforin and CX3CR1 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. CSF-resident CAR T cells exhibit improved memory characteristics.

A. Frequency of CD8+ CAR T cells expressing selected tissue residence, differentiation, and cytotoxic proteins in the PB vs. CSF on day 28 post CAR T cell infusion. Bars show mean values. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 6 patients.

B. Abundance of canonical T cell subsets in CD8+ CAR T cells from patients’ PB and CSF on day 28 post infusion. Bars show mean values. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 6 patients.

C. Heat map indicating z-score normalized median expression of all CyTOF markers assessed in PB and CSF CD8+ CAR T cell canonical subsets. Proteins were arranged by hierarchical clustering; n = 6 patients.

D. CD8+ CAR T cell subsets abundance, defined by the expression of tissue-resident markers CD69 and CD103 on day 28 post infusion PB and CSF. Bars show mean values. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 6 patients.

E. TGFβ isoforms concentrations (pg ml−1) of pre-lymphodepletion CSF, and day 28 serum and CSF. Bars show mean values. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; n = 8 patients.

F. Experimental workflow to interrogate the immunologic response of CSF-derived CAR T cells.

G. Abundance of canonical T cell subsets in CD8+ CAR T cells from patients’ day 28 BM and CSF before and after culture with CD19+ tumor cells. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 2 patients.

H. Representative histograms of the activation marker CD69 in CD8+ CAR T cells from patients’ day 28 BM and CSF after co-culture with CD19+ tumor cells.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Panel F was created with biorender.com.

Next, intrigued by the residence memory signature of CAR T cells in the CSF, we also analyzed the abundance of tissue-resident memory (TRM) subsets using CD103 and CD69 expression. CAR T cells in the CSF were significantly dominated by CD69+ and/or CD103+ resident subsets, consistent with previous studies on CD8+ T cells in the human brain (36,37), while PB CAR T cells were dominated by non-resident cells (Fig. 5D). Given the dominating TRM phenotype in the CNS and the known literature regarding the role of combinational IL-15 and TGFβ in TRM cell development and survival (38), we evaluated the levels of TGFβ isoforms in the CSF pre-lymphodepletion, CSF day 28, and PB day 28 post-infusion. Our analysis detected TGFβ isoforms 1 and 2 in both the CSF and the PB, while isoform 3 was undetected (Figure 5E). Furthermore, TGFβ levels were significantly lower in the CSF compared to the PB, and similar to IL-15, TGFβ -1 and -2 levels were independent of CAR T cell therapy, suggesting that the combination of high IL-15 and low TGFβ in the CSF compared to the PB, supports TRM CAR T cell development and survival in the CNS.

Next, we sought to determine the anti-tumor response of CSF-resident CAR T cells. To achieve this, we cultured matched patients’ day 28 CSF and BM CAR T cells (antigen-experienced CAR T cells) as control, with a 3T3 cell line expressing CD19 for 7 days (39), then evaluated any changes in phenotype or activation status (Fig. 5F). Following CD19 tumor co-culture, day 28 CSF-resident CAR T cells exhibited a significant shift in phenotype from a predominantly memory-like phenotype to an effector memory-like phenotype, suggestive of a secondary effector response (40) (Fig. 5G). In both groups, we also observed a similar abundance of an effector memory-like phenotype and equivalent levels of the activation marker CD69 post-culture, supportive of CAR-specific functionality in CSF-resident samples in response to CAR stimulation (Fig. 5G–H). Collectively, these data support that CD8+ CAR T cells establish a CNS memory niche maintained by high IL-15 and low TGFβ, characterized by high expression of memory phenotypic and residence markers, low expression of cytotoxic and exhaustion markers, and functionally can be reactivated and mediate a recall-like response upon engagement with the CAR.

CAR T cells metabolically rewired by CSF possess improved metabolic fitness and anti-leukemic activity.

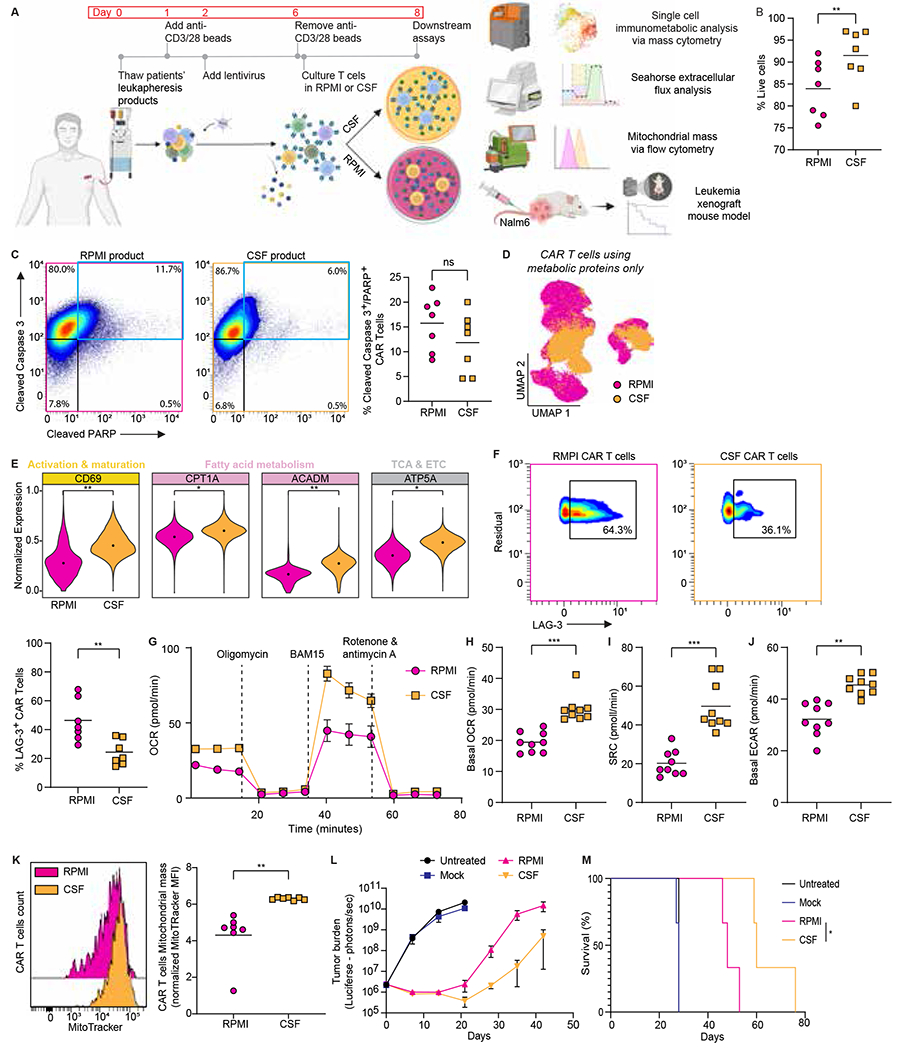

Given the importance of less differentiated memory-like T cells in the context of adoptive cell therapy (40,41), we asked whether we could harness the immunometabolic adaptations found in the CSF-derived CAR T cells to produce superior CAR T cells with memory-like features. Following the transduction of stimulated leukapheresis products (from our patient cohort) with our CD19 CAR construct and removal of anti-CD3/28 stimulation beads, we split the T cell products and cultured half in RPMI and half in CSF with standard manufacturing concentrations of IL-2 and IL-15 for 40 hours (Fig. 6A). We first evaluated the effect of the different media on cell viability and growth. We found high viability (>85%) in both conditions, with significantly higher viability in CSF cultured products (Fig. 6B) and decreased fold expansion (Supplementary Fig. 7), consistent with our previous results in experiments culturing CAR T cells in CSF. Given the scarcity of nutrients in CSF, we evaluated the apoptotic signal via the expression of the activated apoptotic mediators cleaved caspase 3 and PARP (42), including both live and dead single cells, for this comparison. Both culture conditions showed similar levels of the activated apoptotic mediators, indicating that CAR T cells can be viably produced in CSF (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. CAR T cells metabolically rewired by CSF possess improved metabolic fitness and anti-leukemic activity.

A. Experimental workflow for CAR T cell production in RPMI or CSF and subsequent assays.

B. Viability of CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF; A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 7 patients.

C. Mass cytometry representative contour plots and frequencies of cPARP+ and cCASP3+ in all live and non-viable CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF; A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 7 patients.

D. Metabolic state UMAP of CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF considering the expression of metabolic proteins only; n = 7 patients.

E. Normalized (99.9th percentile) expression of all statistically significant proteins of CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF. The median metal intensity (MMI) for each protein in each timepoint is represented by black dots. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 7 patients.

F. Mass cytometry representative contour plots and frequencies of LAG-3+ CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF; A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 7 patients.

(G to J) Metabolic rate as measured by Seahorse analysis of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF under resting and challenge conditions. Data are mean of n = 9 replicate wells; n = 3 patients.

K. Representative histogram of MitoTracker expression and normalized median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MitoTracker in CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF. A two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze data; n = 7 patients.

L. Analysis of tumor burden. NSG mice were injected intravenously with 1.0×10^6 Nalm6 leukemia cells and treated with 5.0× 10^5 mock or CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF four days after tumor infusion. Tumor burden measured in Flux (photons/sec) by bioluminescent imaging was evaluated once weekly. Data are mean ± s.d.; n = 3 mice per group.

M. Survival of mice treated with CAR T cells produced in RPMI or CSF analyzed with the Log-rank Mantel-Cox test.

For all panels p-values are represented as; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Panel A was created with biorender.com.

Next, we compared the single cell immunometabolic state between the two product culture conditions and revealed distinct states between conditions (Fig. 6D). Specifically, CSF products had significantly higher expression of CD69 (as seen in patients’ CSF samples), key enzymes in fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation by the electron transport chain (CPT1A, ACADM, ATP5A), hallmarks of memory T cell metabolism (43,44) (Fig. 6E), and less LAG-3+ CAR T cells (Fig. 6F). Intrigued by the different metabolic states the CAR T cell products exhibited, we assessed their bulk metabolic features by measuring glycolytic and oxygen consumption rates via Seahorse metabolomics analysis. Compared to RPMI, CSF products had increased basal oxygen consumption, higher spare respiratory capacity, and higher basal glycolysis (Fig. 6G–J). Given the increased metabolic activity and mitochondrial reserve of CSF products, we sought to quantify the mitochondrial mass of these products using MitoTracker, a fluorescent dye staining mitochondria in live cells. Consistent with our mass cytometry and Seahorse data, the CSF products contained significantly more mitochondrial mass than the RPMI products (Fig. 6K). Finally, to assess the antitumor function of the two products in vivo, NSG mice were inoculated with Nalm6 leukemic cells and treated four days later with RPMI or CSF-manufactured CAR T cell products. We observed enhanced tumor control and prolonged survival in mice treated with CSF-manufactured products, indicating greater antitumor efficacy of the CAR T cells produced in CSF compared to RPMI (Fig. 6L–M).

Discussion

Activation, differentiation, function, and microenvironment interact to reprogram cellular metabolism, and metabolic plasticity is one of the hallmarks of T cell immunity. A more comprehensive understanding of CAR T cell immunometabolism can elucidate strategies to optimize adoptive cell therapy. Using patient-derived samples, we investigated, for the first time to our knowledge, the spatiotemporal immunometabolic landscape of CD19 CAR T cell therapy in patients. We revealed context-dependent metabolic adaptation of CAR T cells, linking CAR T cell metabolic state, activation, differentiation, function, and microenvironment. Specifically, compared to the peripheral blood, we found low lipid availability, high IL-15, and low TGFβ in the central nervous system microenvironment, promoting immunometabolic adaptation, including lipolytic signature and memory properties of CAR T cells. We show that pharmacological inhibition of lipolysis in cerebrospinal fluid leads to decreased survival of these cells. Moreover, CAR T cell production in cerebrospinal fluid enhanced metabolic fitness and antileukemic activity.

Our findings are supported by clinical data showing CD19 CAR T cell therapy to be effective in clearing CNS leukemia and maintaining durable remission, with improved overall survival in patients with isolated CNS disease compared to patients with bone marrow alone or combined bone marrow and CNS disease (45,46). In a pre-clinical model, we also previously demonstrated that intracerebroventricular delivery of CD19 CAR T cells leads to enhanced antitumor activity against both CNS and systemic malignancy and a greater memory phenotype and CAR T cell function (47). These findings suggest that enhanced immunometabolic fitness is related to improved CAR T cell function in the CNS.

We found elevated levels of the memory T cell homeostatic cytokine IL-15 in patients’ CNS microenvironment, independent of lymphodepletion or CAR T cell infusion, which correlated with memory properties of the CD8+ CAR T cells in the CSF. Homeostatic cytokines are mainly produced by nonhematopoietic tissue cells and are considered to be secreted in a tissue-restricted manner. In the CNS, IL-15 is produced by astrocytes and microglia cells (48–50) and is known to promote T cell-mediated neuroinflammatory diseases (51,52). Notably, IL-15 signaling has been shown to potentiate adoptive cell therapy by preserving the stem-cell memory phenotype of CD19 CAR T cells, improving survival, metabolic fitness, enhancing persistence, and antitumor activity (53–55), further supporting the hypothesis that the high levels of IL-15 in the patients’ CSF promote stem cell memory-like properties of CD8+ CAR T cells in patients CNS. We also found low levels of TGFβ in the CSF compared to the PB, independent of CAR T cell therapy.

IL-15 and TGFβ combination has been found to promote the development and survival of tissue-resident memory T cells (38,56), and indeed, we found a greater abundance of a TRM phenotype in the CSF-resident CD8+ CAR T cells. Human studies have shown an association between tumor infiltrating TRM T cells and an enhanced response to immunotherapy and favorable clinical outcomes in cancer patients (57). Additionally, in a preclinical model, exposure to TGF-β during CAR T cell manufacturing produces stem-like TRM CAR T cells with enhanced efficacy against solid and liquid tumors (58). Compared to the CSF, in the PB, the significantly elevated levels of immunosuppressive TGFβ, unopposed by IL-15, along with the significantly increased levels of IL-5 and IL-12, could drive the observed effector-like phenotype and contraction of post-infusion CD8+ CAR T cells (30,31,59,60).

The CSF is poor in nutrients and relatively hypoxic (34,61,62). Along with the elevated level of IL-15 in the CSF leading to memory-like properties, we show nutrient scarcity (predominantly exogenous fatty acids) and increased expression of the lipolytic protein LAL in CD8+ CAR T cells in the CSF compared to the PB. Previous studies showed that IL-15-derived CD8+ memory T cells can survive in lipid-depleted media (63) and perform intracellular lipolysis by LAL (32). Moreover, LAL deficiency leads to decreased lymphopoiesis and frequency of CD8+ memory T cells (64), and the alteration of lipid metabolism, characterized by upregulation of intrinsic fatty acid synthesis as part of the metabolic adaptation to the CNS microenvironment was shown in metastatic ALL and breast cancer (65–67). Furthermore, we demonstrate that LAL pharmacological inhibition leads to decreased survival of CD8+ CAR T cells in the lipid-deprived CNS microenvironment. These support that in the lipid-deprived CNS microenvironment, CAR T cells upregulate the intrinsic breakdown of fatty acids to support their survival and proliferation, potentially by the lipolytic enzyme lysosomal acid lipase.

Intriguingly, we also observed overexpression of the enzymes HK2 and LDHA in the CSF. While proliferating cells exposed to hypoxia convert glucose to lactate, and enhanced hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) activity promotes glycolytic metabolism (68), the effect of hypoxia and HIF on CD19 CAR T cell function and fate determination hasn’t yet been investigated. Interestingly, actively cycling CAR T cells from a patient with a decade-long leukemia remission showed upregulation in LDHA and oxidative phosphorylation pathways, suggesting Warburg-like aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in CAR T cells with long-term persistence (69).

Intrigued by our ex vivo and in vitro results, we harnessed CSF-induced metabolic reprogramming to enhance CAR T cell function. CAR T cells produced in CSF before adoptive transfer acquired a distinct immunometabolic state, with increased oxidative phosphorylation capacity and mitochondrial mass leading to enhanced antitumor efficacy. Modulating CAR T cell metabolism is a promising strategy to optimize adoptively transferred T cells, and several pre-clinical studies have demonstrated how metabolic modifications affect CAR T cell differentiation, function, and fate. For example, over-expressing proline dehydrogenase 2 in CAR T cells reprogrammed proline metabolism in CD8+ CAR T cells and increased their mitochondrial mass, oxidative phosphorylation, and antitumor efficacy (70). Additionally, inhibiting the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier during CAR T cell manufacturing induced greater chromatin accessibility of pro-memory genes and led to an enhanced stem cell memory-like phenotype and greater antitumor function (71). Mechanistically, producing CAR T cells in CSF leads to transient glucose restriction, which has been shown to promote long-lived memory T cells with enhanced antitumor properties (72–74). Yet, given the broad metabolomic difference between CSF and RPMI, the entire mechanism by which producing CAR T cells in CSF improves fitness and efficacy will need to be further investigated.

The CNS is considered an immune-privileged site and a sanctuary niche for leukemia (75). Our work sheds light on the immunometabolic heterogeneity of CAR T cells with respect to their functional status and tissue microenvironment over time. These findings suggest that the CNS modulates CD19 CAR T cells to establish an advantageous memory niche.

Our study was not without limitations. Patients’ clinical samples are scarce, especially BM and CSF samples which require invasive procedures, limiting our study to day 28 post-infusion. Additionally, in our discovery cohort, all patients were in complete remission and CNS negative status by day 28 disease evaluation, precluding us from studying CAR T cell dysfunction or long-term activation. Therefore, the results cannot exclude the possibility of patient-specific features contributing to our results. Nevertheless, our data based on patient-derived samples of nineteen patients across four time points and three tissue compartments delineated the spatiotemporal immunometabolic landscape of CD19 CAR T cell therapy, highlighting the CNS as an essential metabolic, memory-like niche. These findings offer new insights into CAR T cell biology and provide potential metabolic strategies to improve adoptive cell therapy.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

The spatiotemporal immunometabolic landscape of CD19-targeted CAR T cells from patients reveals metabolic adaptations in specific microenvironments that can be exploited to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of CAR T cells.

Acknowledgements

This reported research includes work performed in the Integrated Mass Spectrometry Shared Resource and in the Analytical Cytometry Core supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. L.G. is the recipient of the Hyundai Hope on Wheels Young Investigator grant.

Footnotes

Authors’ Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Frigault MJ, Maus MV. State of the art in CAR T cell therapy for CD19+ B cell malignancies. J Clin Invest 2020;130:1586–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawalekar OU, O’Connor RS, Fraietta JA, Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD Jr., et al. Distinct Signaling of Coreceptors Regulates Specific Metabolism Pathways and Impacts Memory Development in CAR T Cells. Immunity 2016;44:380–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1507–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldoss I, Khaled SK, Wang X, Palmer J, Wang Y, Wagner JR, et al. Favorable Activity and Safety Profile of Memory-Enriched CD19-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Adults with high-risk Relapsed/Refractory ALL. Clin Cancer Res 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brentjens RJ, Riviere I, Park JH, Davila ML, Wang X, Stefanski J, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood 2011;118:4817–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg L, Haas ER, Vyas V, Urak R, Forman SJ, Wang X. Single-cell analysis by mass cytometry reveals CD19 CAR T cell spatiotemporal plasticity in patients. Oncoimmunology 2022;11:2040772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madden MZ, Rathmell JC. The Complex Integration of T-cell Metabolism and Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2021;11:1636–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artyomov MN, Van den Bossche J. Immunometabolism in the Single-Cell Era. Cell Metab 2020;32:710–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann FJ, Mrdjen D, McCaffrey E, Glass DR, Greenwald NF, Bharadwaj A, et al. Single-cell metabolic profiling of human cytotoxic T cells. Nat Biotechnol 2021;39:186–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine LS, Hiam-Galvez KJ, Marquez DM, Tenvooren I, Madden MZ, Contreras DC, et al. Single-cell analysis by mass cytometry reveals metabolic states of early-activated CD8(+) T cells during the primary immune response. Immunity 2021;54:829–44 e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn WB, Broadhurst D, Begley P, Zelena E, Francis-McIntyre S, Anderson N, et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 2011;6:1060–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan S, Kind T, Cajka T, Hazen SL, Tang WHW, Kaddurah-Daouk R, et al. Systematic Error Removal Using Random Forest for Normalizing Large-Scale Untargeted Lipidomics Data. Anal Chem 2019;91:3590–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B, Zhao D, Chen F, Frankhouser D, Wang H, Pathak KV, et al. Acquired miR-142 deficit in leukemic stem cells suffices to drive chronic myeloid leukemia into blast crisis. Nat Commun 2023;14:5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 2001;125:279–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Y, Pang Z, Xia J. Comprehensive investigation of pathway enrichment methods for functional interpretation of LC-MS global metabolomics data. Brief Bioinform 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen CB, Dam SH, Barnkob MB, Leipold MD, Purroy N, Rassenti LZ, et al. cyCombine allows for robust integration of single-cell cytometry datasets within and across technologies. Nat Commun 2022;13:1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahl PJ, Hopkins RA, Xiang WW, Au B, Kaliaperumal N, Fairhurst AM, et al. Met-Flow, a strategy for single-cell metabolic analysis highlights dynamic changes in immune subpopulations. Commun Biol 2020;3:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Chang WC, Wong CW, Colcher D, Sherman M, Ostberg JR, et al. A transgene-encoded cell surface polypeptide for selection, in vivo tracking, and ablation of engineered cells. Blood 2011;118:1255–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geltink RIK, Kyle RL, Pearce EL. Unraveling the Complex Interplay Between T Cell Metabolism and Function. Annu Rev Immunol 2018;36:461–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber DL, Yudanin NA, Restifo NP. Human memory T cells: generation, compartmentalization and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:24–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendriks J, Gravestein LA, Tesselaar K, van Lier RA, Schumacher TN, Borst J. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat Immunol 2000;1:433–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller KT, Waldron E, Grupp SA, Levine JE, Laetsch TW, Pulsipher MA, et al. Clinical Pharmacology of Tisagenlecleucel in B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:6175–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varanasi SK, Kumar SV, Rouse BT. Determinants of Tissue-Specific Metabolic Adaptation of T Cells. Cell Metab 2020;32:908–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Donnell JM, Alpert NM, White LT, Lewandowski ED. Coupling of mitochondrial fatty acid uptake to oxidative flux in the intact heart. Biophys J 2002;82:11–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 1999;401:708–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabo PA, Miron M, Farber DL. Location, location, location: Tissue resident memory T cells in mice and humans. Sci Immunol 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biasco L, Izotova N, Rivat C, Ghorashian S, Richardson R, Guvenel A, et al. Clonal expansion of T memory stem cells determines early anti-leukemic responses and long-term CAR T cell persistence in patients. Nat Cancer 2021;2:629–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bishop EL, Gudgeon N, Dimeloe S. Control of T Cell Metabolism by Cytokines and Hormones. Front Immunol 2021;12:653605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Cytokine control of memory T-cell development and survival. Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:269–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apostolopoulos V, McKenzie IF, Lees C, Matthaei KI, Young IG. A role for IL-5 in the induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. Eur J Immunol 2000;30:1733–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vignali DA, Kuchroo VK. IL-12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat Immunol 2012;13:722–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Sullivan D, van der Windt GJ, Huang SC, Curtis JD, Chang CH, Buck MD, et al. Memory CD8(+) T cells use cell-intrinsic lipolysis to support the metabolic programming necessary for development. Immunity 2014;41:75–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum AI, Rujoi M, Huang AY, Du H, Grabowski GA, Maxfield FR. Chemical screen to reduce sterol accumulation in Niemann-Pick C disease cells identifies novel lysosomal acid lipase inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1791:1155–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S, Johanson CE. A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp Neurol 2015;273:57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galletti G, De Simone G, Mazza EMC, Puccio S, Mezzanotte C, Bi TM, et al. Two subsets of stem-like CD8(+) memory T cell progenitors with distinct fate commitments in humans. Nat Immunol 2020;21:1552–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mix MR, Harty JT. Keeping T cell memories in mind. Trends Immunol 2022;43:1018–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smolders J, Heutinck KM, Fransen NL, Remmerswaal EBM, Hombrink P, Ten Berge IJM, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells populate the human brain. Nat Commun 2018;9:4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackay LK, Wynne-Jones E, Freestone D, Pellicci DG, Mielke LA, Newman DM, et al. T-box Transcription Factors Combine with the Cytokines TGF-beta and IL-15 to Control Tissue-Resident Memory T Cell Fate. Immunity 2015;43:1101–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Wong CW, Urak R, Mardiros A, Budde LE, Chang WC, et al. CMVpp65 Vaccine Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Adoptively Transferred CD19-Redirected CMV-Specific T Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2993–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, Pos Z, Paulos CM, Quigley MF, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med 2011;17:1290–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansen CS, Prokhnevska N, Master VA, Sanda MG, Carlisle JW, Bilen MA, et al. An intra-tumoral niche maintains and differentiates stem-like CD8 T cells. Nature 2019;576:465–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teh CE, Gong JN, Segal D, Tan T, Vandenberg CJ, Fedele PL, et al. Deep profiling of apoptotic pathways with mass cytometry identifies a synergistic drug combination for killing myeloma cells. Cell Death Differ 2020;27:2217–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimeloe S, Burgener AV, Grahlert J, Hess C. T-cell metabolism governing activation, proliferation and differentiation; a modular view. Immunology 2017;150:35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Windt GJ, Everts B, Chang CH, Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity 2012;36:68–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fabrizio VA, Phillips CL, Lane A, Baggott C, Prabhu S, Egeler E, et al. Tisagenlecleucel outcomes in relapsed/refractory extramedullary ALL: a Pediatric Real World CAR Consortium Report. Blood Adv 2022;6:600–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leahy AB, Newman H, Li Y, Liu H, Myers R, DiNofia A, et al. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for CNS relapsed or refractory acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from five clinical trials. Lancet Haematol 2021;8:e711–e22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Huynh C, Urak R, Weng L, Walter M, Lim L, et al. The Cerebroventricular Environment Modifies CAR T Cells for Potent Activity against Both Central Nervous System and Systemic Lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2021;9:75–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee YB, Satoh J, Walker DG, Kim SU. Interleukin-15 gene expression in human astrocytes and microglia in culture. Neuroreport 1996;7:1062–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi SX, Li YJ, Shi K, Wood K, Ducruet AF, Liu Q. IL (Interleukin)-15 Bridges Astrocyte-Microglia Crosstalk and Exacerbates Brain Injury Following Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2020;51:967–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vainchtein ID, Molofsky AV. Astrocytes and Microglia: In Sickness and in Health. Trends Neurosci 2020;43:144–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laurent C, Deblois G, Clenet ML, Carmena Moratalla A, Farzam-Kia N, Girard M, et al. Interleukin-15 enhances proinflammatory T-cell responses in patients with MS and EAE. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2021;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li M, Li Z, Yao Y, Jin WN, Wood K, Liu Q, et al. Astrocyte-derived interleukin-15 exacerbates ischemic brain injury via propagation of cellular immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E396–E405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alizadeh D, Wong RA, Yang X, Wang D, Pecoraro JR, Kuo CF, et al. IL15 Enhances CAR-T Cell Antitumor Activity by Reducing mTORC1 Activity and Preserving Their Stem Cell Memory Phenotype. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:759–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hurton LV, Singh H, Najjar AM, Switzer KC, Mi T, Maiti S, et al. Tethered IL-15 augments antitumor activity and promotes a stem-cell memory subset in tumor-specific T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E7788–E97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, Durett A, Liu E, Dakhova O, et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 2014;123:3750–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borges da Silva H, Peng C, Wang H, Wanhainen KM, Ma C, Lopez S, et al. Sensing of ATP via the Purinergic Receptor P2RX7 Promotes CD8(+) Trm Cell Generation by Enhancing Their Sensitivity to the Cytokine TGF-beta. Immunity 2020;53:158–71 e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okla K, Farber DL, Zou W. Tissue-resident memory T cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2021;218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jung IY, Noguera-Ortega E, Bartoszek R, Collins SM, Williams E, Davis M, et al. Tissue-resident memory CAR T cells with stem-like characteristics display enhanced efficacy against solid and liquid tumors. Cell Rep Med 2023;4:101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen W. TGF-beta Regulation of T Cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2023;41:483–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah S, Grotenbreg GM, Rivera A, Yap GS. An extrafollicular pathway for the generation of effector CD8(+) T cells driven by the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-12. Elife 2015;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Damkier HH, Brown PD, Praetorius J. Cerebrospinal fluid secretion by the choroid plexus. Physiol Rev 2013;93:1847–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huhmer AF, Biringer RG, Amato H, Fonteh AN, Harrington MG. Protein analysis in human cerebrospinal fluid: Physiological aspects, current progress and future challenges. Dis Markers 2006;22:3–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S, Liu X, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature 2017;543:252–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomaraschi M, Bonacina F, Norata GD. Lysosomal Acid Lipase: From Cellular Lipid Handler to Immunometabolic Target. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2019;40:104–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]