Abstract

Cellular senescence is an important factor leading to pulmonary fibrosis. Deficiency of 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1) in mice leads to alleviation of bleomycin (BLM)-induced mouse pulmonary fibrosis, and inhibition of the OGG1 enzyme reduces the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in lung cells. In the present study, we find decreased expression of OGG1 in aged mice and BLM-induced cell senescence. In addition, a decrease in OGG1 expression results in cell senescence, such as increases in the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells, and in the p21 and p-H2AX protein levels in response to BLM in lung cells. Furthermore, OGG1 promotes cell transformation in A549 cells in the presence of BLM. We also find that OGG1 siRNA impedes cell cycle progression and inhibits the levels of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and LaminB1 in BLM-treated lung cells. The increase in OGG1 expression results in the opposite phenomenon. The mRNA levels of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) components, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1/CXCL2, and MMP-3, in the absence of OGG1 are obviously increased in A549 cells treated with BLM. Interestingly, we demonstrate that OGG1 binds to p53 to inhibit the activation of p53 and that silencing of p53 reverses the inhibition of OGG1 on senescence in lung cells. Additionally, the augmented cell senescence is shown in vivo in OGG1-deficient mice. Overall, we provide direct evidence in vivo and in vitro that OGG1 plays an important role in protecting tissue cells against aging associated with the p53 pathway.

Keywords: OGG1, senescence, cell cycle, p53

Introduction

Senescence is irreversible growth inhibition of cells during aging as well as for different cell stimulation sources, including activated oncogenes, cytokines, reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and nucleotide depletion [ 1– 3]. Cellular senescence is accelerated in patients and appears to play a role in aging-associated morbidity. Traditionally, cell senescence is considered to be a beneficial physiological mechanism in the process of development, wound healing and tumor inhibition. However, in recent years, several lines of evidence have demonstrated that senescent cells persist or accumulate, which have harmful consequences. Aging of alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) may be detrimental to lung repair [4]. Depletion of senescent epithelial cells in vitro and ex vivo decreases fibrotic markers [5]. Notably, cellular senescence may play a positive or negative role in regulating organ fibrosis [ 5– 7]. Senescent cells are involved in different pathophysiological processes. The senescence process is characterized by a variety of nonunique markers, including constitutive DNA damage response (DDR) signaling, senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, increased expression of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, p16INK4A ( CDKN2A) and p21CIP1 ( CDKN1A), increased secretion of many bioactive factors, including the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), and reduced expression of the nuclear lamina protein LaminB1 ( LMNB1 ) [ 8, 9]. The p53 transcription factor plays an important role in cellular responses to stress. Its activation in response to DNA damage results in cell growth arrest, allowing for DNA repair, or induces cellular senescence or apoptosis, thereby leading to the maintenance of genome integrity [10].

8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxo-G) is the main product of oxidative DNA damage in cells and one of the most common types of endogenously generated mutagenic base damage [ 11 , 12]. The corresponding DNA repair enzyme is 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase (OGG1), a DNA repair glycosylase that localizes to both the nucleus and mitochondria [ 13– 16], and it has been shown to activate α-SMA polymerization and to increase the levels of α-SMA exposure to stress fibres [17]. OGG1 inhibition mediated by EGFR is involved in the cell transformation induced by wood dust exposure [18]. Our recent study demonstrated that OGG1 enhanced cell transformation and that OGG1 knockout relieved bleomycin (BLM)-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice [14]. Numerous studies have shown that cellular senescence is an important factor in the occurrence and development of a variety of lung diseases [19], so what role does OGG1 play in cellular senescence in lung fibrosis?

In this study, we hypothesize that OGG1 may modulate cell senescence, and we further investigate the mechanisms by which OGG1 affects senescence in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

BLM (S171001) was purchased from Yuanye Bio-Technology (Shanghai, China). Thymidine (V900931) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, USA). The Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit (AP101) and Cell Cycle Staining Kit were purchased from MULTISCIENCES (Hangzhou, China). Horseradish peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA).

Animal experiments

Female SPF wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (20–22 g, 6–8 weeks) and OGG1-knockout (OGG1 ‒/‒) C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China). The BLM-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis was established as described previously [14]. The mice were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (25±3°C, 40–65% humidity) with a 12-h day/night cycle. All animals were allowed free access to food and water ad libitum. WT and OGG1 ‒/‒ mice were randomly assigned to the vehicle group ( n=6) and BLM-treated group ( n=6). Mice in the vehicle group were administered with intratracheal instillation of 50 μL saline (0.9%), and the BLM-treated group was intraperitoneally injected with 50 μL BLM (5 mg/kg) dissolved in saline. Mice were sacrificed on the 21 st day after BLM or saline treatment, and lungs were harvested for the subsequent experiments. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangdong Medical University and carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Mouse genomic DNA derived from the mouse tail was extracted using a MiniBEST Universal Genomic DNA Extraction kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as previously described [20]. Furthermore, genotyping was performed using the primers shown in Table 1. PCR bands were subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and electrophoresis images were obtained by using a gel imaging system. A 490-bp product reflects WT mice, whereas a 429-bp product indicates OGG1-KO mice, revealing the successful disruption of the OGG1 gene.

Table 1 The sequences of the primers used for genotyping

|

Transcript |

Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

|

|

Ogg1-KO-tF1 |

Forward |

GGATGTTGACTTCTCAGTGCTG |

|

Reverse |

GAATGAGTCGAGGTCCAAAG |

|

|

Ogg1-wt-tF1 |

Forward |

TGATGATCATCATCCACAGG |

|

Reverse |

GCAATGTTGTTGTTGGAGGAAC |

Expression and purification of hOGG1 mutants

Briefly, K249Q, D268A or R304W mutation within the hOGG1 coding sequence was generated using the primers listed in Table 2 by using Q5 DNA polymerase (NEB) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were then digested with DpnI (NEB) to remove the template at 37°C for 6 h. DpnI-treated samples were then transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells using the heat-shock method. After transformation, the products were plated on LB-Kanamycin plates and grown overnight at 37°C. Then, isolated colonies were picked and incubated overnight in 5 mL of LB cultures supplemented with kanamycin. All mutants were purified and sequenced to confirm the desired mutations.

Table 2 The sequences of the primers used for the generation of hOGG1 mutants

|

Transcript |

Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

|

|

K249Q |

Forward |

GGCACCCAGGTGGCTGACTGCATCTGC |

|

Reverse |

AGCCACCTGGGTGCCCACTCCAGGCAG |

|

|

D268A |

Forward |

CCCGTGGCCGTCCATATGTGGCACATT |

|

Reverse |

ATGGACGGCCACGGGCACAGCCTGGGG |

|

|

R304W |

Forward |

TTTTTCTGGAGCCTGTGGGGACCTTAT |

|

Reverse |

CAGGCTCCAGAAAAAGTTTCCCAGTTC |

Masson’s trichrome staining

Lung tissues were fixed in 4% polymethylaldehyde for 24 h. After being dehydrated in graded alcohol, the slices were embedded in paraffin and then cut into 4-μm-thick sections using a microtome. After deparaffinization, rehydration and retrieval, sections were subjected to Masson’s trichrome staining as previously described [14]. Microscopy images for histopathology analysis were acquired under a microscope.

Cell culture and transfection

A549 cells (CRM-CCL-185), which have some characteristic lung epithelial cells, and HFL-1 cells (CCL-153) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, USA). BEAS-2B cells (GNHu27) were purchased from the Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection (Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in DMEM or RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, USA) and cultured in a 37°C humidified incubator under 5% CO 2. Negative control siRNA (NC), OGG1 siRNA, p53 siRNA, PCMV-C-FLAG vector (Vector-NC), OGG1 overexpression vector (PCMV-OGG1-FLAG) or OGG1 mutants were transfected into lung cells using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The sequence information is shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Sequence information of negative control siRNA (NC), OGG1 siRNA and p53 siRNA

|

siRNA |

Sense (5′→3′) |

Antisense (5′→3′) |

|

NC siRNA |

UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACG |

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT |

|

OGG1 siRNA |

GCGCAAGUACUUCCAGCUATT |

UAGCUGGAAGUACUUGCGCTT |

|

p53 siRNA-1 |

CUACUUCCUGAAAACAACGTT |

CGUUGUUUUUCAGGAAGUAGTT |

|

p53 siRNA-2 |

GCGCACAGAGGAAGAGAAUTT |

AUUCUCUUCCUCUGUGCGCCG |

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay

The lung cells were seeded into 96-well plates (3×10 3 cells per well) and cultured in culture medium with 6 repeated wells in each group. After treatment with different concentrations (0, 1, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 μg/mL) of BLM for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO 2, the cells were harvested and counted. Cell viability was determined using a CCK8 kit (40203ES80; Yeasen, Shanghai, China). The absorbance was detected at a wavelength of 450 nm with a microplate reader (Multiskan MK-3; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) to observe the cytotoxicity of BLM on lung cells.

Cell apoptosis assay

Lung cells were cultured in a 6-well plate (5×10 5 cells per well). After treatment with different concentrations (0, 10 and 25 μg/mL) of BLM for 24 h, lung cells and the culture supernatant were harvested and washed with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL of binding buffer, and Annexin V-FITC (5 μL) and PI (10 μL) were added. After incubation for 5 minutes at room temperature away from light, the cells were measured and analyzed using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA). Cells tracked from Annexin-V + /PI − (early apoptotic) and Annexin-V +/PI + (late apoptotic) were regarded as apoptotic cells.

SA-β-gal staining

SA-β-gal staining was carried out using the senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) based on the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described [21]. Lung tissues or lung cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, followed by staining overnight with the working solution including 0.05 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d- galactopyranoside (X-gal) at 37°C. Finally, the SA-β-gal-positive cells were observed using the EVOS FL auto imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (5×10 5 cells of each well) and cultured for 24 h. Subsequently, these cells were treated with thymidine (1 mM) for 24 h to synchronize them at the G1/S boundary as previously described [22]. After centrifugation at 170 g for 5 min, these treated lung cells were collected and washed with PBS and fixed with 70% ice-cold ethanol at ‒20°C overnight. The cells were rehydrated in PBS for 15 min and incubated with 500 μL staining buffer for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the cell cycle distribution was measured by flow cytometry on a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, 1 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA by using a Prime ScriptTM RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was then conducted using a SYBR® Premix Ex Taq TM II PCR Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative expression level of the target genes was calculated by the 2 ‒∆∆CT method. GAPDH was used as an internal control. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The primer sequences are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 The sequences of the primers used for qRT-PCR in this study

|

Transcript |

Primer sequence (5′→3′) |

|

|

PTMA |

Forward |

CAGGAGGCTGACAATGAGGT |

|

Reverse |

GCTTGCCCGTAGCTGACTC |

|

|

ANP32B |

Forward |

GACCAGGAAGCACCTGACTC |

|

Reverse |

CATCCTCATCGTCCTCGTCT |

|

|

SSRP1 |

Forward |

CCTTTGACTTTGAAATTGAGACC |

|

Reverse |

TTTTCGCGTTGACAAAATCA |

|

|

PARP1 |

Forward |

GGCCATGATTGAGAAACTCG |

|

Reverse |

CGGATGTTGGCTTCCTTTAC |

|

|

FAM129A |

Forward |

GAGGCTGCTGACCAGAAGAG |

|

Reverse |

AAAAGGCTTGGGCTTCAAAT |

|

|

CBS |

Forward |

CAGACAACCTACGAGGTGGAA |

|

Reverse |

AAAGGTGAACGCCTCCTCAT |

|

|

Reverse |

CCAAGCTTGATACGGCTGTT |

|

|

LBR |

Forward |

TGGCAGTGAGAACCTTTGAA |

|

Reverse |

CAGCAACAGGAAGAGGAACA |

|

|

FILIP1L |

Forward |

CGCAGGCAGTTCAGATTAAA |

|

Reverse |

TCCTCTTTCAGGGTGGTGAC |

|

|

PDLIM1 |

Forward |

TCCTCTGGTGACGGAGGAAG |

|

Reverse |

CATGGCACTTCGGTTGTG |

|

|

LRP10 |

Forward |

AGGGCTTCCTGCTCTCCTAC |

|

Reverse |

CTGCAACCTGCTTCATCAGA |

|

|

TMEM30A |

Forward |

AGCTGGCCGATACTCTTTGA |

|

Reverse |

TGGATCCAACAGCGATGTAA |

|

|

ARRDC4 |

Forward |

AGAAAATGGTTGGCTGTTGG |

|

Reverse |

TGGAACAATCAGACGAGAGG |

|

|

CCND3 |

Forward |

ATTTCCTGGCCTTCATTCTG |

|

Reverse |

CGGGTACATGGCAAAGGTAT |

|

|

ELMOD1 |

Forward |

ACCCCGACGCTATTGAAAA |

|

Reverse |

CAGAAGGCAAGCCTGAAGAG |

|

|

OGG1 |

Forward |

CTGTGTACCGAGGAGACAAGAGC |

|

Reverse |

CCCAGTGGTGATACAGTTGAGC |

|

|

GAPDH |

Forward |

CTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTCGAC |

|

Reverse |

ACGACCAAATCCGTTGACTC |

|

|

LMNB1 |

Forward |

TCGCAAAAGCATGTATGAAGAG |

|

Reverse |

CTCAAGTTTGGCATGGTAAGTC |

|

|

TERT |

Forward |

CAAGTTGCAAAGCATTGGAATC |

|

Reverse |

ACGTAGTCCATGTTCACAATCG |

|

|

IL-8 |

Forward |

TAGCAAAATTGAGGCCAAGG |

|

Reverse |

AAACCAAGGCACAGTGGAAC |

|

|

IL-1α |

Forward |

CTATCATGTAAGCTATGGCCCA |

|

Reverse |

GCTTAAACTCAACCGTCTCTTC |

|

|

IL-1β |

Forward |

TTCGACACATGGGATAACGAGG |

|

Reverse |

TTTTTGCTGTGAGTCCCGGAG |

|

|

CXCL1 |

Forward |

TCTCTCTTTCCTCTTCTGTTCCTA |

|

Reverse |

CATCCCCCATAGTTAAGAAAATCATC |

|

|

CXCL2 |

Forward |

TGCTGCTCCTGCTCCTGGTG |

|

Reverse |

GGGGACTTCACCTTCACACTTTGG |

|

|

IL-6 |

Forward |

CCTTCCAAAGATGGCTGAAA |

|

Reverse |

AGCTCTGGCTTGTTCCTCAC |

Immunofluorescence assay

Briefly, cells were seeded onto laser confocal dishes. After being washed with PBS, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. After incubation with blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature, the cells were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-OGG1 antibody (1:200; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, USA) and monoclonal mouse anti-p53 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, USA) overnight at 4°C. After wash with PBS, the cells were stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (10 μM) for 5 min. Fluorescence images were captured using an FV3000 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay was performed using a co-IP kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were lysed in ice-cold nondenaturing lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After centrifugation at 13,800 g at 4°C for 20 min, the supernatants were harvested and incubated with Flag tag polyclonal antibody agarose resin and rotated at 4°C overnight. After incubation, the resin was washed again, and the protein was eluted using elution buffer. Subsequently, the samples were boiled in loading buffer and subjected to standard SDS-PAGE, followed by western blot analysis with anti-OGG1 and anti-p53 antibodies.

Western blot analysis

After treatment, the cells were subjected to lysis with RIPA buffer containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 13,800 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the protein lysates were collected in the supernatant. The protein concentration was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology). Subsequently, 50 μg of protein from each sample was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, which were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C. After washing three times in TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were then washed and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (ECL; Millipore, Billerica, MA). The relative densities of the bands were then analyzed using the ImageJ software (Image J 1.42q; NIH, Bethesda, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: OGG1 (ab124741; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), NB100-106 (Novus Biologicals), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) (ab32020; Abcam), Lamin B1 (17416S), p53 (2425S), p-p53 (9284S), p21 (2947S), p-H2AX (9718S), N-cadherin (13116S) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, USA), FN1 (BA1771; Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China), α-SMA (GTX100034; GeneTex, Irvine, USA) and Tubulin (D110022; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical analysis software SPSS 20.0. Data are presented as the mean±SD. The differences between the two groups were analysed by independent sample t test. The differences among multiple groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. When P was less than 0.05, significance was considered statistically significant.

Results

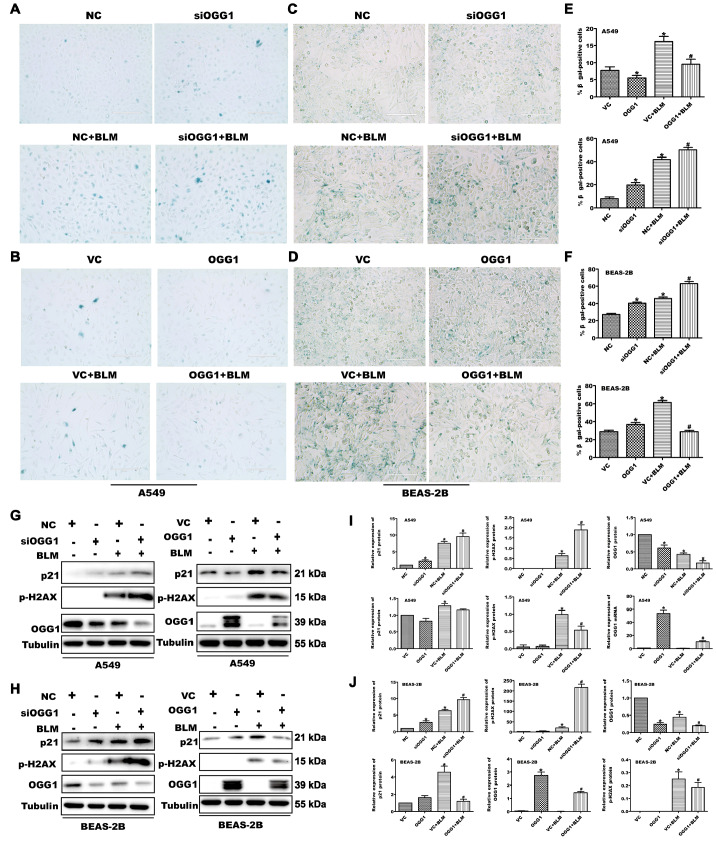

OGG1 knockdown promotes and exogenously overexpressing OGG1 inhibits senescent lung cells

To determine the role of OGG1 during cellular senescence, we first measured the expression levels of OGG1 in aged mice and senescent lung cells. The results showed that 18-month-old mice had lower TERT and higher p21 protein expression, along with decreased OGG1 protein expression, than 2-month-old mice ( Supplementary Figure S1A,B). BLM was reported to induce cell senescence in lung cells [ 23, 24]. First, we used CCK-8 and Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis assays to observe the toxicity of different concentrations of BLM on A549 and BEAS-2B cells. When lung cells were treated with 25 μg/mL of BLM, the cell viability was decreased by approximately 20% compared to that of the control group ( Supplementary Figure S1C–E). Subsequently, we measured the expression level of OGG1 protein in BLM-treated A549 and BEAS-2B cells. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1F–K, after treatment of A549 and BEAS-2B cells with BLM (25 μg/mL) for 24 h, these cells exhibited a typical cell senescence phenotype, as indicated by the increased SA β-gal activity with a flat as well as enlarged morphology, which was accompanied by upregulation of p21 and p-H2AX and downregulation of OGG1 protein expression, suggesting a potential role of OGG1 in cell senescence. Subsequently, to confirm the function of OGG1 during cell senescence, we observed the impact of silencing and overexpressing OGG1 on the senescence of lung cells using β-gal staining and on the levels of p21 and p-H2AX protein by western blot analysis. We first confirmed the knockdown or overexpression efficiency of siRNA or plasmid transfection ( Supplementary Figure S2). As demonstrated in Figure 1, A549 and BEAS-2B cells were transfected with siRNA (siRNA-NC or siOGG1) or plasmid (Vector-NC or OGG1) for 24 h and subsequently administered with BLM (25 μg/mL) for 24 h. OGG1 knockdown augmented the increase in SA-β-gal-positive lung cells and upregulation of p21 and p-H2AX proteins induced by BLM. Furthermore, OGG1 overexpression obviously alleviated BLM-induced increases in SA-β-gal-positive cells and p21 and p-H2AX protein levels. In addition, we used human embryo lung fibroblasts HFL-1 cells to study the effect of OGG1 on the senescence of lung cells, and we observed the same phenomenon ( Supplementary Figure S3). Taken together, OGG1 plays an important role in inhibiting the cellular senescence process.

Figure 1 .

Silencing of OGG1 promotes and overexpressing OGG1 inhibits cell senescence in lung cells

A549 and BEAS-2B cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 (VC or OGG1) for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. (A–D) Representative images of SA β-galactosidase activity staining. Scale bar: 200 μm. (E,F) Statistical analysis results of SA-β-gal-positive lung cells in (A) and (B). (G–J) The protein expression of OGG1, the cellular senescence marker protein p21 and the DNA damage-associated protein p-H2AX were detected by western blot analysis. Tubulin protein was used for endogenous normalization. * P<0.05 vs NC or VC; #P<0.05 vs NC+BLM or VC+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

OGG1 modulates cell transformation of A549 cells in the presence of BLM

To investigate whether OGG1 affects cell transformation in A549 cells treated with BLM, we assessed the effect of OGG1 on the levels of cell transformation markers by western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2, after BLM treatment, the levels of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers such as fibronectin (FN1), N-cadherin and α-SMA proteins were significantly elevated in A549 cells, indicating that BLM can induce EMT generation. Moreover, we found that silencing of OGG1 downregulated and overexpressing OGG1 upregulated the levels of FN1, N-cadherin and α-SMA proteins in the presence of BLM. Collectively, these results indicate that OGG1 inhibits cellular senescence and thereafter may promote the cell transformation of these lung cells.

Figure 2 .

OGG1 modulates cell transformation in A549 cells in the presence of BLM

A549 cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 (A,C), VC or OGG1 (B,D) 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. EMT markers, including FN1, N-cadherin and α-SMA proteins, were detected by western blot analysis. *P<0.05 vs NC or VC; #P<0.05 vs NC+BLM or VC+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

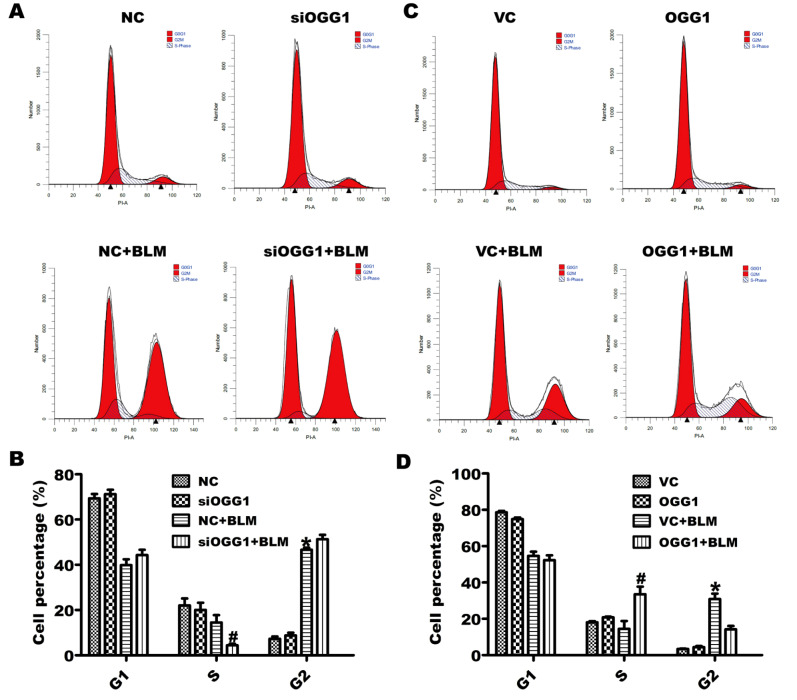

OGG1 regulates the cell cycle in A549 cells

Cell growth arrest is a key event in cellular senescence, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors have been implicated in cell cycle progression. We further explored the effects of OGG1 on the cell cycle in lung cells. A549 cells were transfected with different siRNAs (NC or siOGG1) or plasmids (VC or OGG1) for 24 h and subsequently treated with BLM (25 μg/mL). As shown in Figure 3, BLM administration induced an accumulation of cells in G2/M. OGG1 knockdown reduced the number of cells in S phase, and OGG1 overexpression increased the number of lung cells in S phase in the presence of BLM. Collectively, these results revealed that OGG1 may play accelerative roles in the cell cycle progression of lung cells.

Figure 3 .

OGG1 modulates cell cycle transition in BLM-induced lung cells

A549 cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 (VC or OGG1) for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. (A,C) The population of cells at the G1, S and G2/M phase was detected by flow cytometry. (B,D) The statistical analysis results of lung cell numbers in different stages of the cell cycle in (A) and (C). *P<0.05 vs NC or VC; # P<0.05 vs NC+BLM or VC+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

OGG1 regulates TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and protein expressions in A549 cells

Telomerase deficiency is an important hallmark of senescence, and TERT is a component of telomerase [25]. Downregulated level of LaminB1 has become a common marker of senescence [26]. In this study, we also investigated the impact of OGG1 on TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and protein levels in lung cells. As shown in Figure 4, TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and proteins were decreased in BLM-treated A549 cells. Moreover, OGG1 knockdown alleviated TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and protein levels in BLM-treated A549 cells. However, OGG1 overexpression showed the opposite results. These data indicate that OGG1 modulates the levels of TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and protein involved in the repression of cell senescence.

Figure 4 .

OGG1 regulates TERT and LaminB1 mRNA and protein expressions in BLM-induced A549 cells

A549 cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 (VC or OGG1) for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. The expressions of TERT and LaminB1 mRNA (A,B) and proteins (C–F) in A549 cells was detected by qPCR and western blot analysis, respectively. Tubulin protein was used for endogenous normalization. *P<0.05 vs NC or VC; #P<0.05 vs NC+BLM or VC+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

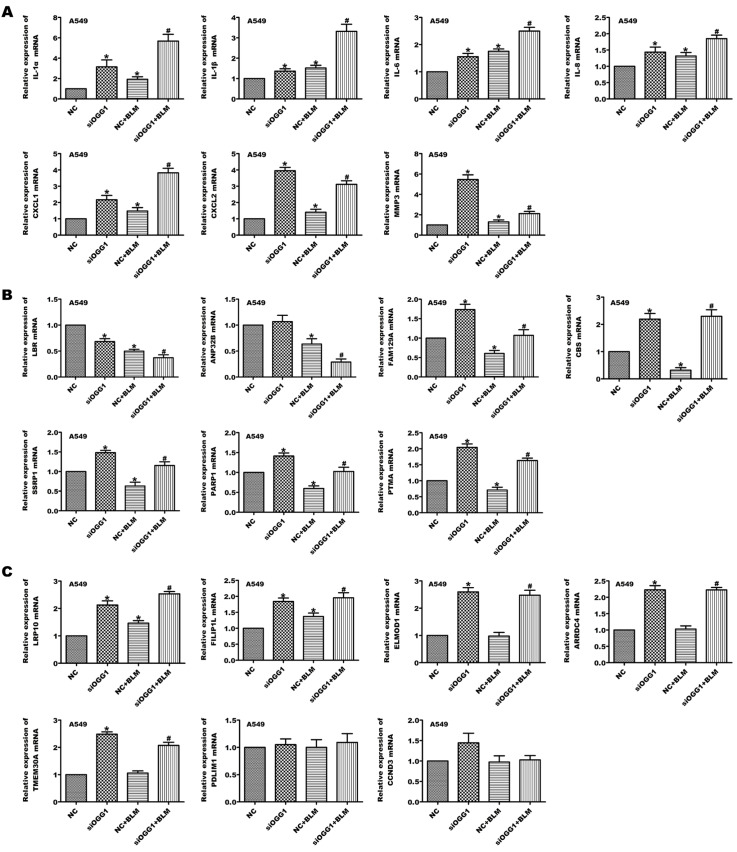

Senescence-related factors are altered in OGG1-knockdown A549 cells

Senescent cells secrete cytokines, chemokines and proteinases. We then explored the effects of OGG1 silencing on the levels of SASP factors, including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1/CXCL2, and MMP-3 mRNA. As shown in Figure 5A, these SASP factors were obviously enhanced in A549 cells after BLM treatment, and OGG1 knockdown increased BLM-induced levels of SASP factors. Based on these findings, including several reduced and elevated transcripts with senescence identified by Gorospe and his colleagues [27], we further validated some of these transcripts in OGG1-silenced A549 cells treated with BLM. Lamin B receptor (LBR), acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family member B (ANP32B), family with sequence similarity 129 member A (FAM129A), cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS), structure-specific recognition protein (SSRP) and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mRNA levels with reduced transcripts in senescence were decreased in BLM-treated A549 cells, but only LBR and ANP32B mRNA levels were further reduced in OGG1-silenced A549 cells in the presence of BLM ( Figure 5B). Furthermore, OGG1 knockdown elevated LRP10 (LDL receptor-related protein 10) and FILIP1L (filamin A interacting protein 1 like) mRNA levels increased by BLM treatment. Downregulation of OGG1 expression augmented ELMOD1 (ELMO domain containing 1), ARRDC4 (arrestin domain containing 4) and TMEM30A (transmembrane protein 30A) mRNA levels with or without BLM administration ( Figure 5C). Together, these results suggest that OGG1 may influence cell senescence by regulating senescence-related factors.

Figure 5 .

OGG1 knockdown modulates senescence-related factors in A549 cells

A549 cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. The levels of SASP (A), including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1/CXCL2, and MMP-3, reduced transcripts with senescence (B), including LBR, ANP32B, FAM129A, CBS, SSRP1, PARP1, and PTMA, increased transcripts with senescence (C), including LRP10, FILIP1L, ELMOD1, ARRDC4, TMEM30A, PDLIM1 and CCND3, were detected by qPCR assay. *P<0.05 vs NC; #P<0.05 vs NC+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

p53 signaling is involved in the inhibitory role of OGG1 on senescence in lung cells

Phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15 is associated with DNA damage, and the p53 signaling pathway plays an important role in cell senescence. Subsequently, we explored the impact of OGG1 knockdown and overexpression on the p53 signaling pathway. We found that OGG1 silencing elevated the level of phosphorylated p53 in A549 cells after BLM treatment. However, overexpression of OGG1 inhibited the ratio of p-p53/p53 ( Figure 6A–D). We further explored whether OGG1 modulates p53 activation during cellular senescence by binding to p53. We first observed that OGG1 was colocalized with p53 in A549 cells by immunofluorescence assay ( Figure 6E). We also explored the interaction between OGG1 and p53 in A549 cells through a coimmunoprecipitation assay. We transfected A549 cells with pCMV-OGG1-FLAG plasmids and purified Flag-tagged OGG1 using an anti-Flag affinity gel. The amount of Flag-tagged OGG1 and coprecipitated p53 were detected by western blot analysis using anti-OGG1 antibody and anti-p53 antibody, respectively. The results showed that OGG1 coprecipitated with p53 ( Figure 6F). Furthermore, we investigated whether silencing of p53 reverses OGG1 knockdown-induced cell senescence in the presence of BLM in lung cells. The silencing effect of p53 siRNA was first verified by western blot analysis ( Figure 6G). The results demonstrated that p53 siRNA inhibits the increases in SA-β-gal-positive cells caused by OGG1 knockdown in the presence of BLM in lung cells ( Figure 6H–K). The above results indicate that OGG1 could inhibit the activation of p53 by binding to it and prevent cell senescence in lung cells.

Figure 6 .

OGG1 regulates p53 signaling in BLM-induced lung cells

(A–D) A549 cells were transfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 (VC or OGG1) for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. The expressions of p-p53 and p53 protein in lung cells was detected by western blot analysis. (E) Immunofluorescence assay showing the colocalization of OGG1 with p53 in A549 cells. (F) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed the interaction of OGG1 with p53 in A549 cells. (G) Western blot analysis was used to determine the silencing effect of p53 siRNA. p53 siRNA was cotransfected with siRNA-NC or siOGG1 for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h. (H,I) Representative images of SA β-galactosidase activity staining. Scale bar: 200 μm. (J,K) The expressions of OGG1, p21, p-H2AX, p-p53 and p53 proteins were detected by western blot analysis. Tubulin protein was used for endogenous normalization. *P<0.05 vs NC+BLM; #P<0.05 vs siOGG1+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

Loss of DNA repair activity of OGG1 promotes lung cell senescence

Subsequently, we further explored whether the inhibitory effect of cellular senescence induced by OGG1 is associated with the DNA repair activity of 8-oxoG. As demonstrated in Figure 7, the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells and the levels of p-p53/p53, p21 and p-H2AX in OGG1 mutants, including OGG1 K249Q (249), D268A (268), and R304W (304)-overexpressing A549 cells treated with BLM, were enhanced compared to OGG1 WT-transfected A549 cells in the presence of BLM, indicating that loss of DNA repair function of OGG1 leads to cell aging.

Figure 7 .

Impairment in the DNA repair activity of OGG1 promotes lung cell senescence

A549 cells were transfected with VC, OGG1, OGG1 K249Q (249), D268A (268), or R304 W (304) for 24 h and then treated with 25 μg/mL BLM for 24 h (A) Representative images of SA β-gal activity staining. (B) Statistical analysis results of SA-β-gal-positive lung cells in (A). (C,D) The expressions of OGG1, p21, p-H2AX, p-p53 and p53 in lung cells were detected by western blot analysis. Tubulin protein was used for endogenous normalization. *P<0.05 vs VC; #P<0.05 vs VC+BLM; & P<0.05 vs OGG1+BLM. Data are expressed as the mean±SD of the experiments performed in triplicate.

Cell senescence is augmented in OGG1-deficient mice

Finally, we further validated the association of OGG1 with cell senescence by using OGG1-deficient (OGG1 –/–) mice with or without BLM administration. We first confirmed the OGG1 –/– mice by PCR on genomic DNA samples obtained from mouse tails of OGG1 –/– and WT mice. By identifying a 429-bp product in the OGG1 –/– mice and a 490-bp product in the WT mice, we confirmed that the OGG1 gene was destroyed in the OGG1 –/– mice and that these OGG1-knockout mice were homozygous ( Figure 8A). The lack of OGG1 protein in OGG1-knockout mice was further verified by western blot analysis ( Figure 8B). In addition, OGG1 –/– mice were subjected to BLM treatment for 21 days to determine the function of OGG1 in cell senescence in an in vivo model of pulmonary fibrosis. As shown in Figure 8C,D, BLM induced extensive collagen fibers, damaged lung alveoli, and elevated SA-β-gal-positive cells. Moreover, we observed that severe pulmonary fibrosis was alleviated in OGG1-knockout mice. In addition, SA-β-gal-positive cells were increased in OGG1-deficient mice compared with WT mice with or without BLM treatment.

Figure 8 .

Cell senescence is augmented in OGG1-knockout mice

(A) Genomic PCR of wild-type (WT) and OGG1 tail DNA: 429 bp OGG1 and 490 bp OGG1 (WT) amplification product. (B) The expressions of OGG1 protein in lung tissues from WT and OGG1-knockout mice were detected by western blot analysis to further verify the lack of OGG1 protein. WT and OGG1–/– mice were intratracheally treated with 50 μL of physiological saline (normal control) or BLM on day 0. Then, the mice were sacrificed at 21 days posttreatment. (C) The lung sections were stained with Masson. Scale bar: 300 μm. (D) The lung sections were stained with SA-β-gal. Scale bar: 300 μm .

Discussion

Aging is the initiating factor of multiple diseases, and cellular senescence is an important tumor suppression mechanism, but it also leads to a harmful cellular phenotype that affects tissue homeostasis and regeneration [28]. OGG1 plays an important role in aging-related diseases; therefore, we tried to clarify the direct effect and possible mechanism of OGG1 on the aging process. Here, we reported that the expression of the DNA base excision repair enzymes OGG1 and TERT was decreased in the lung tissue of 18-month-old mice compared to 2-month-old mice ( Supplementary Figure S1). This suggests that OGG1, like TERT, decreases in content as organs and cells age. Additionally, our results showed that OGG1 knockdown reduced but OGG1 overexpression elevated TERT level in lung cells ( Figure 4). BLM is a family of complex glycopeptides that exert antitumor effects, and one of its toxic side effects is pulmonary fibrosis [29]. Notably, previous studies reported that BLM can also result in alveolar epithelial cell senescence [ 30, 31]. In the current study, OGG1 reduction was found to lead to cellular senescence in BLM-treated lung cells and BLM-induced lung fibrosis in mice, as shown in Figures 1 and 8, suggesting that under physiological conditions, OGG1 maintains a steady-state balance and prevents cell senescence.

In IPF and an experimental pulmonary fibrosis model, alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) showed obvious signs of aging [32]. AEC IIs are progenitor cells of the alveolar epithelium. In vitro, A549 cells are commonly used as a replacement for primary AECs because AECs are difficult to obtain and maintain in culture ex vivo [ 23, 24, 33]. Cellular senescence is associated with activation of p53, leading to activation of p21 CIP1 and cell cycle arrest. p53 is the main transcriptional regulator of p21. In this study, we also explored whether OGG1 affects p53 activation. We found that silencing of OGG1 by siRNA led to increased levels of p-p53/p53 in response to BLM, while exogenously overexpressing OGG1 showed the opposite results. A previous report showed that mimicking constitutive phosphorylation (that is, activation) in a p53 mouse model resulted in striking aging features [34]. Numerous studies showed that p53 plays a critical role in the maintenance of genomic integrity through its role in the DNA damage response [35]. These data indicate that OGG1 inhibits BLM-induced cell damage resulted from the decrease in the p53 activation response to BLM and blocks the aging process of cells. Interestingly, we also observed the colocalization of OGG1 with p53 in A549 cells by immunofluorescence assay and the interaction of these two proteins by coimmunoprecipitation. Our results further showed that p53 silencing reduces the increases in SA-β-gal-positive cells induced by OGG1 knockdown in BLM-treated lung cells. The above data reveal that OGG1 binds to p53 to inhibit its activation and impede cell senescence in lung cells. Flow cytometry results demonstrated that OGG1 knockdown decreased the number of lung cells in S phase after exposure to BLM, and OGG1 overexpression showed the opposite results. Overall, we speculated that OGG1 binds to p53 to inhibit p53 activation, restrain p21 expression, and thereafter modulate the cell cycle involved in cellular senescence.

In addition to the activation of p53, phosphorylation at Ser139 of H2AX is one of the signaling pathways associated with DNA damage and serves as one hallmark of senescence. DNA double-strand break (DSB) DSBs are the most damaging among DNA lesions and increase with age, leading to cell death and cellular senescence [ 36, 37]. OGG1 is a DNA glycosylase that initiates BER, while the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) protein complex is the primary responder to DSBs, which are localized to damage sites [38]. In this study, we also demonstrated that OGG1 reduction leads to BLM-induced p-H2AX increase. Exogenous OGG1 leads to BLM-induced p-H2AX reduction, indicating that DNA repair pathways interact and complement each other to jointly resist harmful foreign stimuli in addition to single-strand break repair and join the other DNA repair pathways. Recent reports have shown that the global level of LaminB1, a major component of the nuclear lamina, is reduced in association with aging [ 8, 39], although it is unclear how LaminB1 alterations affect the dynamic alterations seen in chromatin structure and the gene expression profile during senescence. In the present study, we showed that OGG1 enhanced the increase in LaminB1 in response to BLM, suggesting that OGG1 resists the cellular aging progress.

It has been reported that Asp268 is the catalytic residue for excision of 8-oxoG, while Lys249 is responsible for the specific recognition and final alignment of 8-oxoG during base hydrolysis [40]. Another study reported that the mutation of Arg304 in OGG1 can impair the DNA repair activity of 8-oxoG and is identified as the critical factor for senescence acceleration in mice [41]. Subsequently, we further explored whether the inhibitory effect of cellular senescence induced by OGG1 is associated with the DNA repair activity of 8-oxoG. In this study, we found that the extent of cellular senescence in OGG1 K249Q-, D268A- and R304W-transfected cells was higher than that in OGG1 WT-treated cells. These data show that mutant OGG1, which has lost its DNA repair function, also lost its effect on cell aging.

Based on our results, we can speculate that OGG1 directly binds with p53 and inhibits the activity of p53, thus inhibiting the p53-p21 signaling pathway. p53 signaling is the crucial downstream target of OGG1 involved in aging regulation. In our study, we found that the percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells and the p-p53/p53 and p21 levels were increased in OGG1 mutant-treated A549 cells, including OGG1 K249Q (249), D268A (268), and R304W (304), compared to OGG1 WT-transfected A549 cells, suggesting that the impairment of OGG1 repair activity of OGG1 might be responsible for the inhibitory effects of OGG1 on cellular senescence, which might be mediated by the p53-p21 signaling pathway.

We have previously reported that OGG1 inhibits the generation of ROS, alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction, and increases the expression of IL-1β induced by particulate matter [42]. OGG1 deficiency leads to a reduction in pulmonary fibrosis development, and the mechanism is partly based on the promotion of the TGF/Smad signaling pathway by OGG1, which aggravates the development of pulmonary fibrosis [15]. Aging can lead to a reduction in lung stem cells, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress damage and telomerase shortening, and ultimately leads to the inability of lung cells to maintain homeostasis, which plays important roles in the occurrence and development of IPF, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other pulmonary diseases [16]. However, it is worth noting that cellular senescence may exert a positive and negative regulatory role in organ fibrosis. In some senescence-related diseases, such as IPF, liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride and polycystic kidney, after inhibiting aging, the progression of organ fibrosis is intensified, which is manifested by severe DNA damage, uncontrolled cell proliferation and apoptosis, and disturbance of ECM secretion [ 6, 7]. Based on these findings, we proposed a schematic overview of the effects of OGG1 on senescence during pulmonary fibrosis ( Figures 9). Increasing evidence suggests that OGG1 plays multiple roles in IPF. We speculate that OGG1 can participate in IPF pathology in a direct or indirect way, causing excessive proliferation of fibroblasts, and that reduced OGG1 alleviates the pathological progression of IPF. At the initial stage of pulmonary fibrosis, OGG1 mainly repairs damaged lung epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts to prevent cell damage and aging and is an important performer in charge of maintaining the normal operation of cells and preventing cell aging. However, when the damage is greater than the repair capacity of these lung cells, OGG1 promotes the abnormal proliferation of lung interstitial cells and fibroblasts and promotes the excessive secretion of collagen by fibroblasts to compensate for the atrophy and collapse of tissues caused by the injury and death of alveolar epithelial cells, becoming the promoter of pulmonary fibrosis in this period.

Figure 9 .

A schematic overview of the effects of OGG1 on cell senescence during pulmonary fibrosis

OGG1 participates in two processes (normal repair and excessive repair) in IPF. Under normal physiological conditions, when lung epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts are damaged by BLM, OGG1 inhibits the p53-p21 signaling pathway by interacting with p53, inhibiting cell senescence and maintaining normal functions (normal repair). In the pathological environment of pulmonary fibrosis, when lung epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts are induced by BLM, OGG1 can perform normal repair functions and maintain normal cell functions (normal repair). However, due to the continuous damage to lung cells, more OGG1 is needed to promote the repair of damage, and the regulation of OGG1 expression is uncontrolled. Subsequently, abnormally upregulated OGG1 induces EMT in the anti-aging lung epithelial cells and abnormal activation in the anti-aging lung fibroblasts through TGF-β/Smads, ultimately leading to the occurrence of IPF.

In summary, cellular senescence plays an important role in the occurrence and development of pulmonary fibrosis. The signals and therapeutic targets related to cellular aging are also of great significance in normal lung homeostasis regulation, and blocking these known profibrotic signals may have opposite effects, so targeted therapy for pulmonary fibrosis should be more accurate.

Supporting information

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data is available at Acta Biochimica et Biphysica Sinica online.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. NSFC81570062, NSFC82070061, and NSFC82270074), the Social Talent Fund Project of Tangdu Hospital and The Fourth Military Medical University (No. 2021SHRC008), the Guangdong Medical Science Foundation (No. A2019456), and the Guangdong Medical University Scientific Research Fund (No. GDMUM201801).

References

- 1.Chandrasekaran A, Idelchik MPS, Melendez JA. Redox control of senescence and age-related disease. Redox Biol. . 2017;11:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herranz N, Gil J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest. . 2018;128:1238–1246. doi: 10.1172/JCI95148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. . 2014;509:439–446. doi: 10.1038/nature13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RM, Liu G. Cell senescence and fibrotic lung diseases. Exp Gerontology. . 2020;132:110836. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao C, Guan X, Carraro G, Parimon T, Liu X, Huang G, Mulay A, et al. Senescence of alveolar type 2 cells drives progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. . 2021;203:707–717. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1274OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng X, Wang H, Song X, Clifton AC, Xiao J. The potential role of senescence in limiting fibrosis caused by aging. J Cell Physiol. . 2020;235:4046–4059. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters DW, Blokland KEC, Pathinayake PS, Burgess JK, Mutsaers SE, Prele CM, Schuliga M, et al. Fibroblast senescence in the pathology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. . 2018;315:L162–L172. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00037.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loaiza N, Demaria M. Cellular senescence and tumor promotion: is aging the key? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. . 2016;1865:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol. . 2018;28:436–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mijit M, Caracciolo V, Melillo A, Amicarelli F, Giordano A. Role of p53 in the regulation of cellular senescence. Biomolecules. . 2020;10:420. doi: 10.3390/biom10030420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes DE, Lindahl T. Repair and genetic consequences of endogenous DNA base damage in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Genet. . 2004;38:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markkanen E. Not breathing is not an option: how to deal with oxidative DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) . 2017;59:82–105. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L, Wang Y, Lin Z, Zhou X, Chen T, He H, Huang H, et al. Mitochondrial OGG1 protects against PM2.5-induced oxidative DNA damage in BEAS-2B cells. Exp Mol Pathol. . 2015;99:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Chen T, Pan Z, Lin Z, Yang L, Zou B, Yao W, et al. 8‐Oxoguanine DNA glycosylase modulates the cell transformation process in pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting Smad2/3 and interacting with Smad7. FASEB J. . 2020;34:13461–13473. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901291RRRRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Jiang D, Zhang L. A thermophilic 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase from Thermococcus barophiluss Ch5 is a new member of AGOG DNA glycosylase family . Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. . 2022;54:1801–1810. doi: 10.3724/abbs.2022072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Song K, Yu J, Da LT. Computational investigations on target-site searching and recognition mechanisms by thymine DNA glycosylase during DNA repair process. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. . 2022;54:796–806. doi: 10.3724/abbs.2022050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo J, Hosoki K, Bacsi A, Radak Z, Hegde ML, Sur S, Hazra TK, et al. 8-Oxoguanine DNA glycosylase-1-mediated DNA repair is associated with Rho GTPase activation and α-smooth muscle actin polymerization. Free Radical Biol Med. . 2014;73:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staffolani S, Manzella N, Strafella E, Nocchi L, Bracci M, Ciarapica V, Amati M, et al. Wood dust exposure induces cell transformation through EGFR-mediated OGG1 inhibition. Mutagenesis. . 2015;30:487–497. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gev007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho SJ, Stout-Delgado HW. Aging and lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol. . 2020;82:433–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Furuichi M, Xu P, Tsuzuki T, Sekiguchi M, Nakabeppu Y. Ogg1 knockout-associated lung tumorigenesis and its suppression by Mth1 gene disruption. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 902–905 . [PubMed]

- 21.Le R, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Wang H, Lin J, Dong Y, Li Z, et al. Dcaf11 activates Zscan4-mediated alternative telomere lengthening in early embryos and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. . 2021;28:732–747.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang H, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Chen T, Yang L, He H, Lin Z, et al. miR-5100 promotes tumor growth in lung cancer by targeting Rab6. Cancer Lett. . 2015;362:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian Y, Li H, Qiu T, Dai J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Cai H. Loss of PTEN induces lung fibrosis via alveolar epithelial cell senescence depending on NF‐κB activation. Aging Cell. . 2019;18:e12858. doi: 10.1111/acel.12858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong D, Gao F, Shao J, Pan Y, Wang S, Wei D, Ye S, et al. Arctiin-encapsulated DSPE-PEG bubble-like nanoparticles inhibit alveolar epithelial type 2 cell senescence to alleviate pulmonary fibrosis via the p38/p53/p21 pathway. Front Pharmacol. . 2023;14:1141800. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1141800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Z, Daquinag AC, Fussell C, Zhao Z, Dai Y, Rivera A, Snyder BE, et al. Age-associated telomere attrition in adipocyte progenitors predisposes to metabolic disease. Nat Metab. . 2020;2:1482–1497. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radspieler MM, Schindeldecker M, Stenzel P, Forsch S, Tagscherer KE, Herpel E, Hohenfellner M, et al. Lamin‑B1 is a senescence‑associated biomarker in clear‑cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. . 2019;18:2654–2660. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casella G, Munk R, Kim KM, Piao Y, De S, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Transcriptome signature of cellular senescence. Nucleic Acids Res. . 2019;47:11476. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. . 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T, De Los Santos FG, Phan SH. The bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1627: 27-42 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Aoshiba K, Tsuji T, Nagai A. Bleomycin induces cellular senescence in alveolar epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. . 2003;22:436–443. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00011903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasper M, Barth K. Bleomycin and its role in inducing apoptosis and senescence in lung cells-modulating effects of caveolin-1. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. . 2009;9:341–353. doi: 10.2174/156800909788166501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faner R, Rojas M, MacNee W, Agustí A. Abnormal lung aging in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. . 2012;186:306–313. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0282PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milara J, Ballester B, Safont MJ, Artigues E, Escrivá J, Morcillo E, Cortijo J. MUC4 is overexpressed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and collaborates with transforming growth factor β inducing fibrotic responses. Mucosal Immunol. . 2021;14:377–388. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-00343-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu D, Ou L, Clemenson Jr GD, Chao C, Lutske ME, Zambetti GP, Gage FH, et al. Puma is required for p53-induced depletion of adult stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. . 2010;12:993–998. doi: 10.1038/ncb2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams AB, Schumacher B. p53 in the DNA-damage-repair process. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. . 2016;6:a026070. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vijg J, Dong X. Pathogenic mechanisms of somatic mutation and genome mosaicism in aging. Cell. . 2020;182:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White RR, Vijg J. Do DNA double-strand breaks drive aging? Mol Cell. . 2016;63:729–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anand SK, Sharma A, Singh N, Kakkar P. Entrenching role of cell cycle checkpoints and autophagy for maintenance of genomic integrity. DNA Repair. . 2020;86:102748. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, Zhao TY, Common JE, Lunny D, Lane EB, et al. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol. . 2013;200:605–617. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalhus B, Forsbring M, Helle IH, Vik ES, Forstrøm RJ, Backe PH, Alseth I, et al. Separation-of-function mutants unravel the dual-reaction mode of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. Structure. . 2011;19:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi JY, Kim HS, Kang HK, Lee DW, Choi EM, Chung MH. Thermolabile 8-hydroxyguanine DNA glycosylase with low activity in senescence-accelerated mice due to a single-base mutation. Free Radical Biol Med. . 1999;27:848–854. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, Liu G, Lin Z, Wang Y, He H, Liu T, Kamp DW. Pro‐inflammatory response and oxidative stress induced by specific components in ambient particulate matter in human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ Toxicol. . 2016;31:923–936. doi: 10.1002/tox.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.