Abstract

Stroke survivors frequently experience difficulties in daily activities, such as bathing, feeding, and mobility. This study aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of a computer-adaptive test-Longshi scale (CAT-LS) for assessing activities of daily living (ADL) in stroke survivors. This cross-sectional study collected data using an electronic application. The ADL function of stroke survivors in rehabilitation departments of hospitals was assessed using both the CAT-LS and BI. Correlations between the CAT-LS and Barthel index (BI) and concurrent validity were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation test and multiple linear regression. Interrater reliability was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient based on a two-way random effect. The internal consistency of the CAT-LS was assessed using Cronbach’s coefficient (α) and corrected item-total correlations. Overall, 103 medical institutions in China were used in this study. In total, 7151 patients with stroke were included in this study. The CAT-LS classified patients into three ADL groups (bedridden, domestic, and community) with significantly different BI scores (P < 0.05). The CAT-LS results obtained using the decision-tree scoring model were consistent with the scores for each BI item. A strong correlation was observed between CAT-LS and BI (Pearson’s r: 0.6–0.894, P < 0.001). The CAT-LS demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α, 0.803–0.894) and interrater reliability (ICC, 0.928–0.979). CAT-LS is time-efficient and requires < 1 min to administer. The CAT-LS is a reliable and valid tool for assessing ADL function in stroke survivors and can provide rapid and accurate assessments that reduce the burden on healthcare professionals. Further validation of this tool in other populations and settings is necessary.

Study registration number: No.: ChiCTR2000034067; http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=54770.

Keywords: Activities of daily living, Barthel index, Computer adaptive test-Longshi Scale, Stroke

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Health occupations, Medical research

Introduction

Stroke survivors frequently experience difficulties in daily activities and quality of life1. A significant proportion of stroke survivors, ranging from 36 to 89%, experience one or more functional disabilities2. Therefore, assessing activities of daily living (ADL) is crucial for clinicians in determining treatment methods and enhancing independence3. A short, reliable, and valid ADL measure is required to be clinically useful and reduce the burden on clinicians and patients4.

ADL includes basic ADL (BADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL)5. BADL measures, including the Barthel index (BI) and Functional Independence Measure, tend to have ceiling effects, whereas IADL measures tend to have floor effects6. The BI is a measure of public-domain ADL that is commonly used in clinical trials to assess patients with stroke7. The tool assesses the following 10 activities related to BADLs: bowel management, bladder control, grooming, feeding, toilet use, transferring, movement, dressing, climbing stairs, and bathing8. These activities are fundamental to living in a social world. Many IADL scales are closely related to environmental performance9. IADL scales comprised varying numbers of items covering the domains of housework, work/leisure, outdoor activities, dressing outside, shopping, and eating with guests9. However, simultaneously assessing all ADLs and IADLs may require more time, and would be physically demanding for both the patient and the clinician. Some patients do not need to be evaluated for all activities. For example, some long-term bedridden patients are completely unable to walk or climb stairs and do not need to be asked about this item by the assessor.

Therefore, to address this problem, our previous study developed the Longshi scale (LS), which is a graphical tool for assessing ADL based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) guidelines10,11. The scale categorizes patients into the following three groups based on ADL capability: bedridden, domestic, and community12. Each group includes 3 different items, which provides a practical solution for reducing the ADL scale length by linking ADL assessment with the scope of activities. The LS has demonstrated high interrater reliability (0.877–0.955) and test–retest reliability (0.921–0.984)11. Additionally, using smartphone video technology in LS for assessing ADL in stroke survivors can be effectively implemented in remote clinical settings13.

To streamline the LS evaluation process, we integrated computerized adaptive testing (CAT) with the inner logic of the programming in LS(CAT-LS)14,15. Computerized adaptive testing (CAT) is a proven method for the efficient, reliable, and valid assessment of health-related functions16,17. CAT leverages item response theory to dynamically select the most relevant questions based on prior responses, resulting in more concise questionnaires with enhanced precision18, and reducing the administrative burden on patients19,20, which is similar to the LS-categorizing assessment rule.

Nevertheless, the validation and interrater reliability of CAT-LS in hospitalized stroke survivors remain unestablished. Consequently, the study aims to evaluate CAT-LS concurrent validity, internal consistency, and inter-rater reliability in stroke survivors. Building upon the robust psychometric characteristics demonstrated by conventional LS assessments11,13,15,21, we postulated that CAT-LS would emerge as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing ADL in our target population.

Methods

Study design and participants

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted in 103 hospitals in 23 cities in China from September 2018 to August 2019 and involved 7151 cerebral stroke survivors using cluster sampling. The specific inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals aged between 18 and 90 years and (2) those diagnosed with a stroke. The type of stroke was determined based on the initial diagnosis from medical history, according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases22. The exclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

CAT-LS development procedure

The CAT-LS development procedure comprises three phases. In phase 1, a total of 11 items from the BI, IADL, and ICF were selected to comprise the traditional paper version of the LS (including bladder and bowel management, feeding, entertainment, toileting, grooming, and bathing, cooking, community mobility, shopping, social interaction, transfer out of bed and return, and transfer out of the door and return) (Table 1)23,24. Out of the total 11 items, seven originated from BI while the remaining four were derived from ICF and IADL. Over 80% of the ICF items primarily focused on “activities”, which encompass “individuals performing specific tasks or actions”, as well as “physical functions”24. It is crucial not to overlook the social participation requirements of patients24. Selection of the 4 social participation entries in ICFs and IADLs that are of most concern to patients based on a previous study (Table 1)11. In phase 2, a CAT system based on the LS decision tree was presented, and validation datasets were collected using a smart mobile application named ‘Quicker Recovery Line (QRL)’23,25. In phase 3, concurrent validity and inter-rater reliability of CAT-LS and the correlation with BI in stroke survivors were calculated.

Table 1.

Comparison of the proposed CAT-LS, BI, and ICF.

| Items | BI item | IADL | CAT-LS | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feeding | Eating with guests | F1b feeding | b525 defecation functions\d550 eating |

| 2 | Bathing | F2b grooming and bathing | d510 washing oneself | |

| 3 | Grooming | F2b grooming and bathing | d510 washing oneself | |

| d520 caring for body part | ||||

| 4 | Dressing | |||

| 5 | Bowel management | F1a bladder and bowel management | ||

| 6 | Bladder management | F1a bladder and bowel management | b620 urination functions | |

| 7 | Toileting | F2a toileting | d530 toileting\d5308 Toileting, other specified | |

| 8 | Bed/chair transfer | Q1: able to transfer out of bed and return | d410 changing basic body position | |

| 9 | Ambulation | Outdoor activities | F3a community mobility | d450 walking |

| 10 | Stair climbing | |||

| 11 | Outdoor activities | Q2: able to transfer out of the door and return | d4602 moving around outside the home and other building | |

| 12 | Leisure | F1c entertainment | d3600 using telecommunication devices | |

| 13 | Meal preparation | F2c cooking | d640 doing housework\d630 preparing meals | |

| 14 | Shopping | F3b shopping | d6200 Shopping | |

| 15 | Transportation | F3c social interaction | d470 Using transportation |

Subscales: motor = items 1–11; and social participation = 12–15.

Data collection

The assessment was conducted using smart mobile devices (mobile phones or tablets). Before the formal assessment, the investigators explained the study contents to all participants.

All data were recorded and uploaded on the ‘QRL’. First, one healthcare professional logged into the QRL account and created electronic forms online. The demographic information of all participants, including basic information and health status, was recorded. Second, patients’ BI and CAT-LS scores were on a face-to-face interview basis and were collected by interviewing stroke survivors, caregivers, and doctors21,25. Once the data collection was completed, it could not be changed. The data were from our previous study23. Missing data were handled by conducting reinterviews.

ADL evaluation

We assessed Activities of Daily Living (ADL) using two methods: the CAT-LS and the BI scale26,27. For the first day’s assessment, the choice of whether to use the CAT-LS or the BI scale was made randomly each time. The performance of the CAT-LS and BI scales was assessed by medical professionals and therapists respectively. To check the consistency in evaluations between different raters, the same assessors evaluated the ADL of stroke survivors once more on the second day, measuring the interrater reliability of the CAT-LS. These assessments were carried out one after the other during a single clinical visit, and we recorded the time taken for each assessment in seconds.

The BI was designed in traditional electronic format with the same specifications as the paper version. Physicians and therapists can submit assessment results only after all items are selected. BI consists of 10 ADL tasks, including feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowel management, bladder management, toileting, bed/chair transfer, wheelchair, climbing stairs, and range based on the level of physical assistance required to complete the task. These are based on the level of physical assistance required to complete the task28. Most of the items were scored in a range of 0–10, where scores of 0, 5, and 10 indicated an inability to perform the task, need for assistance, and ability to perform the task independently, respectively, for a combined total of 100 points. Bathing, wheelchair, and grooming items were scored in a range of 0–5, where scores of 0 and 5 indicated inability to perform the task and full ability to perform the task independently, respectively. In addition, the Bed\chair transfer items were scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 15, where a score of 5–10 indicated the need for assistance in completing the task, and a score of 15 indicated a full ability to complete the task independently (Table 2).

Table 2.

Barthel index scores and the capability to perform ADL.

| Items | Unable to perform the task | Needs assistance | Fully independent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Bathing | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Grooming | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Dressing | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Bowel management | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Bladder management | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Toileting | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Bed/chair transfer | 0 | 5–10 | 15 |

| Wheelchair | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Climbing stairs | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Range | 0 | 100 |

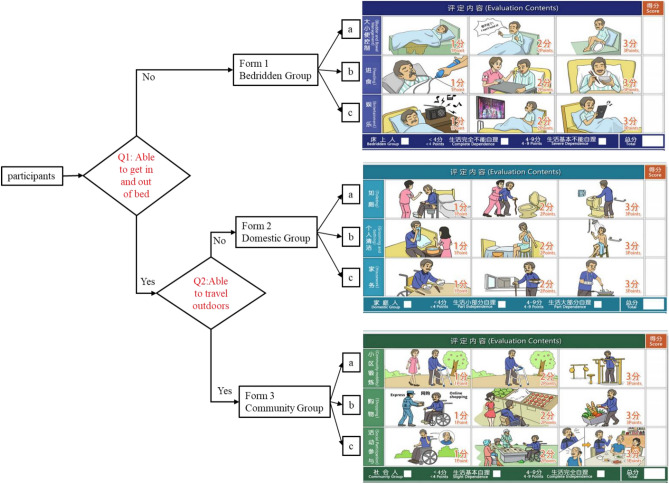

The CAT-LS used item response theory. Item response theory is the statistical basis for testing the fit of the data model to estimate the difficulty of the questions and the respondent’s ability29. The CAT-LS decision tree functions as a flowchart, commencing with a primary question—“Can you get off the bed?”, and subsequently diverging into different branches based on the outcomes of the initial decision. Further branching occurs based on the results of a subsequent question—“Can you go outside?”, enabling a visual representation of the outcomes of a comprehensive ADL assessment. This approach facilitates a rapid comprehension of a patient’s ADLs. Participants were asked about their ability to get in and out of bed to begin the assessment30. If they answered “No”, they are categorized in the bedridden group and only the items in Form 1 are displayed on the application interface, including bladder and bowel management, feeding, and entertainment (Fig. 1). If they answered ‘YES’, they were asked a second question regarding their ability to travel outside their house and return. If they answered ‘NO’, they were categorized into the domestic group, and only items in Form 2 were shown, including toileting, personal cleaning, and housework. If they answered ‘YES’, they were categorized into a community group, and only items in Form 3 were evaluated, including community mobility, shopping, and social participation (Fig. 1). Subsequently, individuals only needed to be evaluated on items corresponding to their functional level to accurately estimate the functional level and improve evaluation efficiency.

Figure 1.

Process for CAT-LS assessment.

After categorization, the patients in each group were evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale as follows: (1) bedridden (including bladder and bowel management, feeding, and entertainment), (2) domestic (including toileting, grooming, and housework), and (3) community (including community mobility, shopping, and social participation) groups. Each item corresponded to three multiple-choice questions with different abilities, and all alternatives were presented as a situation map (Fig. 1). Each item was scored as follows: 1 for maximum or complete dependence, 2 for partial independence, and 3 for maximum or complete independence. The evaluation was completed once the three items on the subscale were selected. The total scores of each group were 3–9 (Fig. 1)30, and accordingly, the CAT-LS was categorized into six grades, and subsequently, the CAT procedure ended (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scoring guidelines for the ICF qualifiers.

| From | CAT-LS score | CAT-LS grade | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| From 1 | 3 points | 1 = Complete Dependence | The person does not perform the activity at all |

| From 1 | 4–9 points | 2 = Severe Dependence | The activity is carried out completely dependently; continuous help (guiding, support, or effective help) from others is needed. The person experiences severe problems in performance |

| From 2 | 3 points | 3 = Part Independence | The person can perform the activity in a very limited range |

| From 2 | 4–9 points | 4 = Part Dependence | The activity is carried out independently but sometimes help is needed. There are moderate limitations in performance; the person is less result oriented and less adequate. There are faults in performance |

| From 3 | 3 points | 5 = Slight Dependence | The activity is carried out completely independently; no help from others is needed but mild limitations are present: less frequent use of, the more simplified form of the activity (e.g. only a few functions of technological equipment). The person needs more time, is slower, less energetic, and has difficulties learning something new. The person is less flexible, inventive, creative, and more rigid |

| From 3 | 4–9 points | 6 = Complete Independence | The activity is carried out completely independently; no help from others is needed. There are no limitations, the person carries out the activity at a normal frequency and is adequate, flexible, inventive, and creative (e.g. the person can use all functions of technological equipment) |

Automatic quality control process

In this multicenter study, evaluators obtained the electronic data of CAT-LS and BI from smartphone device terminals located in different centers and were transmitted to the cloud server through the application named ‘QRL’25. Data quality was evaluated using the built-in automatic quality control system of the cloud server. For each day, if the data quality for the same evaluator was compromised, all evaluation data of the evaluator on that day were discarded. The built-in logic of quality control is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Inner logic for automatic quality control.

| Quality control rules |

|---|

| 1. In CAT-LS rated as Bedridden, but in BI the bed chair transfer gain 15 points |

| 2. In CAT-LS is rated as Domestic, but in BI the bed chair transfer gain 0 points, or the total BI score is 0 |

| 3. In CAT-LS rated as Community, but in BI the bed chair transfer gained 0 points, or the total BI score is 0 |

| 4. For Bedridden: 1 point for CAT-LS defecation control, but 10 points for BI defecation control |

| 5. For Bedridden: 3 points for CAT-LS defecation control, but 0 points for BI control |

| 6. For Bedridden: 1 point for CAT-LS feeding, but 10 points for BI feeding |

| 7. For Bedridden: 3 points for CAT-LS feeding, but 0 points for BI feeding |

| 8. For Domestic: 1 point for CAT-LS self-cleaning, but 5 points for BI bathing or decoration |

| 9. For Domestic: 1 point for CAT-LS toileting, but 10 points for BI toileting |

| 10. For Domestic: 3 points for CAT-LS toileting, but 0 points for BI toileting |

| 11. Personal information indicated living alone but defecation or feeding in CAT-LS and BI were low |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 25. The Kruskal–Wallis test, t-test, and chi-square test were performed to analyse mean differences between LS groups (i.e., bedridden, domestic, and community groups). Differences among CAT-LS groups were evaluated by comparing the means and standard deviations of the different scores of the original BI measures.

Internal consistency and concurrent validity

The CAT-LS was trained to predict the total BI scores using the raw scores of each item on the CAT-LS. We utilized generalized linear models with total BI as the dependent variable and each item of LS as the independent variable. The internal consistency of the CAT-LS was assessed using Cronbach’s coefficient (α) and corrected item-total correlations. Pearson’s correlation test and multiple linear regression analysis were used to analyse the concurrent validity of the CAT-LS. Notably, concurrent validity was considered strong if Pearson’s correlation coefficient was ≥ 0.7531.

Interrater reliability

The interrater reliability of the CAT-LS was evaluated using the kappa coefficient (κ) and intraclass correlation coefficient based on a two-way random effect (ICC2,1)32,33. ICC values were categorized as ‘poor’ (ICC < 0.5), ‘moderate’ (0.5–0.75), ‘good’ (0.75–0.9), and ‘excellent’ (ICC > 0.9)33. The kappa values were defined as ‘poor’ (κ < 0.20), ‘fair’ (0.21–40), ‘moderate’ (0.41–60), ‘good’ (0.61–80), and ‘very good’ (κ = 0.81–1.00) agreement32.

Suppliers

A smart mobile application named “Quicker Recovery Line (QRL)”.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of Shenzhen Second People’s Hospital. The study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No.: ChiCTR2000034067) on June 22, 2020. All inpatients or their proxies were invited to participate in this study after obtaining informed consent before collecting their information. All authors confirmed that all methods were carried out following the research protocol approved by the ethics committee.

Results

Population characteristics

Table 5 presents the baseline demographic characteristics of 7151 stroke survivors. The CAT-LS classified 4020 (56.2%), 2050 (28.7%), and 1081 (15.1%) patients into the bedridden, domestic, and community categories, respectively. The mean age of the participants was 67.6 ± 15.0 years, and a statistically significant difference was found in the mean age among the three groups. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity in the community group, affecting 672 (62.16%) participants, followed by diabetes mellitus (255; 23.63%), hyperlipidemia (116; 10.75%), heart disease (172; 15.93%), and kidney disease (25; 2.31%).

Table 5.

Demographic information on stroke survivors.

| Characteristics | Total | Functional status | Kruskal–Wallis/χ2 | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/mean | %/SD | Bedridden group | Domestic group | Community Group | |||||||

| n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | n/mean | %/SD | ||||||

| Total | 7151 | 100.0 | 4020 | 56.2 | 2050 | 28.7 | 1081 | 15.1 | |||

| Type of stroke | Hemorrhagic | 2012 | 28.1 | 1270 | 31.6 | 550 | 26.8 | 192 | 17.8 | 83.0 | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic | 5139 | 71.9 | 2750 | 68.4 | 1500 | 73.2 | 889 | 82.2 | |||

| Age (year) | 67.6 | 15 | 70.1 | 14.7 | 65.2 | 14.8 | 62.2 | 14.2 | < 0.001 | ||

| Duration (month) | 2.5 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 0.068* | ||

| 0.076† | |||||||||||

| 1# | |||||||||||

| Gender | Male | 4303 | 60.2 | 2270 | 56.5 | 1327 | 64.7 | 706 | 65.4 | 52.6 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 2845 | 39.8 | 1748 | 43.5 | 723 | 35.3 | 374 | 34.6 | |||

| Smoke | No | 5398 | 76.1 | 3176 | 79.6 | 1447 | 71.3 | 775 | 72.4 | 60.8 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1694 | 23.9 | 815 | 20.4 | 584 | 28.8 | 295 | 27.6 | |||

| Alcohol | No | 6396 | 90.1 | 3681 | 92.2 | 1788 | 87.8 | 927 | 86.3 | 48.9 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 706 | 9.9 | 311 | 7.8 | 248 | 12.2 | 147 | 13.7 | |||

| Hypertension | No | 1921 | 26.9 | 961 | 23.9 | 551 | 26.9 | 409 | 37.8 | 83.7 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 5223 | 73.1 | 3054 | 76.1 | 1497 | 73.1 | 672 | 62.2 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 5152 | 72.3 | 2856 | 71.3 | 1472 | 72.1 | 824 | 76.4 | 11.1 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 1976 | 27.7 | 1151 | 28.7 | 570 | 27.9 | 255 | 23.6 | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | No | 6427 | 90.2 | 3667 | 91.5 | 1797 | 88.1 | 963 | 89.3 | 19.9 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 699 | 9.8 | 339 | 8.5 | 244 | 12.0 | 116 | 10.8 | |||

| Heart disease | No | 5445 | 76.2 | 2894 | 72.0 | 1643 | 80.3 | 908 | 84.1 | 93.9 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1699 | 23.8 | 1123 | 28.0 | 404 | 19.7 | 172 | 15.9 | |||

| Kidney disease | No | 6835 | 95.8 | 3830 | 95.5 | 1950 | 95.5 | 1055 | 97.7 | 10.9 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 297 | 4.2 | 181 | 4.5 | 91 | 4.5 | 25 | 2.3 | |||

*Comparison between bedridden and domestic groups.

†Comparison between domestic and community groups.

#Comparison between bedridden and community groups.

Classification and regression tree of ADL assessment using CAT-LS

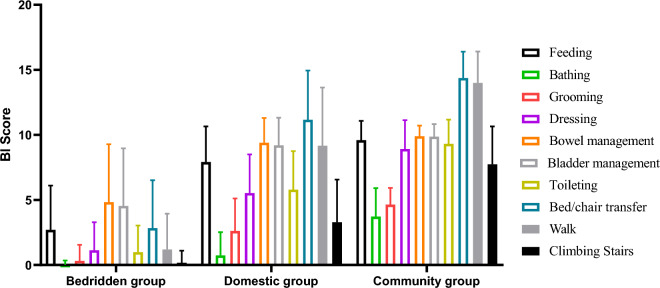

Table 6 displays the BI scores corresponding to the following three groups: bedridden (18.7 ± 18.8), domestic (64.8 ± 18.9), and community (93.5 ± 12.8). Patients in the bedridden group had lower scores than those in the domestic group in the following BI categories: bathing (0.0 ± 0.3), grooming (0.3 ± 1.2), dressing (1.1 ± 2.2), toileting (1.0 ± 2.0), bed/chair transfer (2.8 ± 3.7), walking (1.2 ± 2.8), and climbing stairs (0.2 ± 0.9). In the community group, BI scores for feeding (9.6 ± 1.5), grooming (4.6 ± 1.3), dressing (8.9 ± 2.2), bowel management (9.9 ± 0.8), bladder management (9.9 ± 1.0), toileting (9.3 ± 1.7), bed/chair transfer (14.4 ± 2.0), and walking (14.0 ± 2.4) tended towards the highest scores of 10/15 (Table 6, Fig. 2). Notably, the bed/chair transfer and walking categories had almost perfect scores in the community group. The CAT-LS results based on the decision-tree scoring model were consistent with the scores for each BI item. However, the median scores for 10 BI items significantly differed among the three CAT-LS groups (Table 7).

Table 6.

BI scores in three CAT-LS groups.

| Total BI/items | Bedridden group (N = 4020) | Domestic group (N = 2050) | Community group (N = 1081) | P-value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI | |||||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||||

| Total BI | 18.7 | 18.8 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 64.8 | 18.9 | 64.0 | 65.6 | 92.1 | 12.5 | 91.3 | 92.8 | < 0.001 |

| Feeding | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 9.7 | < 0.001 |

| Bathing | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| Grooming | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 4.6 | 4.7 | < 0.001 |

| Dressing | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 8.9 | 2.2 | 8.8 | 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| Bowel management | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 0.8 | 9.9 | 10.0 | < 0.001 |

| Bladder management | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 9.2 | 2.1 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 1.0 | 9.8 | 9.9 | < 0.001 |

| Toileting | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 9.3 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 9.4 | < 0.001 |

| Bed/chair transfer | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 3.8 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 14.4 | 2.0 | 14.3 | 14.5 | < 0.001 |

| Walk | 1.2 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 9.2 | 4.5 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 14.0 | 2.4 | 13.9 | 14.1 | < 0.001 |

| Climbing stairs | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 7.9 | < 0.001 |

Figure 2.

BI scores of each item among the three CAT-LS groups.

Table 7.

Comparisons of BI-item scores among three CAT-LS groups.

| Comparisons (median difference) | Total BI | Feeding | Bathing | Grooming | Dressing | Bowel management | Bladder management | Toileting | Bed/chair transfer | Walk | Climbing stairs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedridden group vs domestic group | 47.3* | 5.3* | 1.0* | 2.5* | 4.7* | 4.5* | 4.6* | 4.9* | 8.5* | 8.0* | 3.3* |

| Bedridden group vs community group | 75.1* | 6.8* | 4.3* | 4.3* | 8.1* | 5.1* | 5.4* | 8.5* | 11.7* | 12.8* | 8.1* |

| Domestic group vs community group | 27.8* | 1.5* | 3.3* | 1.8* | 3.4* | 0.6* | 0.8* | 3.6* | 3.2* | 4.8* | 4.8* |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

CAT-LS results (CAT-LS grades and LS scores) had a strong correlation with BI scores

Table 8 displays the results of the correlation analysis between the CAT-LS and BI scores of stroke survivors. A strong correlation was observed between the CAT-LS and BI scores (Pearson’s r = 0.894, P < 0.0001), indicating that the CAT-LS grades and item scores were good indicators of the functional status of stroke survivors. Pearson’s r values ranged from 0.529 to 0.799 (P < 0.001) between CAT-LS items and BI total scores and from 0.600 to 0.856 (P < 0.001) between CAT-LS grades and BI items.

Table 8.

Correlation of CAT-LS scores with BI total score and BI item scores.

| CAT-LS items | Total BI | BI item score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | Bathing | Grooming | Dressing | Bowel management | Bladder management | Toileting | Bed/chair transfer | Walk | Stairs | ||

| F1a. Bladder and bowel management | 0.799** | 0.591** | 0.050** | 0.284** | 0.433** | 0.839** | 0.846** | 0.448** | 0.612** | 0.341** | 0.163** |

| F1b. Feeding | 0.752** | 0.769** | 0.081** | 0.331** | 0.471** | 0.639** | 0.635** | 0.451** | 0.597** | 0.419** | 0.186** |

| F1c. Entertainment | 0.700** | 0.615** | 0.070** | 0.264** | 0.448** | 0.645** | 0.643** | 0.404** | 0.570** | 0.353** | 0.158** |

| F2a. Toileting | 0.738** | 0.352** | 0.370** | 0.431** | 0.492** | 0.176** | 0.182** | 0.695** | 0.578** | 0.657** | 0.578** |

| F2b. Grooming and bathing | 0.662** | 0.333** | 0.577** | 0.486** | 0.523** | 0.140** | 0.163** | 0.533** | 0.468** | 0.472** | 0.529** |

| F2c. Housework | 0.529** | 0.229** | 0.439** | 0.344** | 0.454** | 0.098** | 0.108** | 0.454** | 0.348** | 0.396** | 0.469** |

| F3a. Community mobility | 0.649** | 0.300** | 0.411** | 0.354** | 0.491** | 0.143** | 0.141** | 0.475** | 0.501** | 0.588** | 0.566** |

| F3b. Shopping | 0.650** | 0.316** | 0.474** | 0.337** | 0.508** | 0.191** | 0.186** | 0.458** | 0.450** | 0.530** | 0.573** |

| F3c. Social participation | 0.602** | 0.315** | 0.451** | 0.350** | 0.493** | 0.154** | 0.160** | 0.425** | 0.414** | 0.475** | 0.503** |

| CAT-LS grade | 0.894** | 0.747** | 0.600** | 0.697** | 0.799** | 0.635** | 0.643** | 0.829** | 0.841** | 0.856** | 0.761** |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

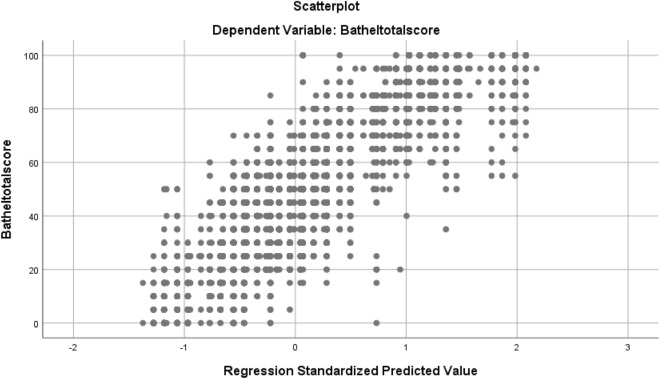

A scatter plot was generated to illustrate the relationship between the CAT-LS and BI scores (Fig. 3), showing the linear fitting results. The plot indicated a positive correlation between CAT-LS results and BI total scores. Moreover, a linear relationship was found between the LS results and BI total scores, and the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.874. High R2 values indicated that the CAT-LS results were closely associated with the model’s predictions of the BI total score. To determine the correlation between the BI scale and CAT-LS scale scores, we propose the formula: BI total score = − 44.9 + 30.44 × LS Grade + 16.14 × (F1a/F2a/F3a) + 6.79 × (F1b/F2b/F3b) − 3.04 × (F1c/F2c/F3c) (R2 = 0.874). F1a represents the score of the bladder and bowel item, F1b represents the score of the feeding item, F1c represents the score of the entertainment item, F2a represents the score of the toileting item, F2b represents the score of the grooming and bathing item, F2c represents the score of the housework item, F3a represents the score of the exercise in the community mobility item, and F3b represents the score of the shopping item. F3c represents the social participation score.

Figure 3.

Scatter diagram illustrating the CAT-LS results (CAT-LS grades and LS scores) and BI total scores.

Floor and ceiling effects, internal consistency, and interrater reliability of the CAT-LS

Table 9 presents the floor and ceiling effects, internal consistency, interrater reliability, and concurrent validity of the CAT-LS. The floor and ceiling effects of CAT-LS grade were 19.2%/11.7%, respectively. Internal consistency, as measured using Cronbach’s α, was high for all three subscales (bedridden, 0.847; domestic, 0.723; and community, 0.868). The corrected item-total and mean interitem correlations were > 0.4, indicating good internal consistency. Interrater reliability was assessed using ICC2,1 and kappa values. The ICC2,1 values for interrater reliability were high for all three subscales and CAT-LS grades (bedridden group: 0.974; domestic group: 0.928; community group: 0.979; and CAT-LS grade: 0.964). The kappa values for the three groups ranged from 0.898–0.927, 0.837–0.877, and 0.841–0.866, indicating substantial agreement. The Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the bedridden, domestic, and community groups were 0.852, 0.764, and 0.685, respectively, indicating good and strong concurrent validity.

Table 9.

Distribution, internal consistency, reliability, and validity of CAT-LS.

| Bedridden group | Domestic group | Community group | CAT-LS grade | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor/ceiling effect (%) | – | – | – | 19.2/11.7 |

| Internal consistency | ||||

| Cronbach α | 0.857 | 0.803 | 0.912 | 0.964 |

| Corrected-total correlation | 0.724–0.750 | 0.619–0.721 | 0.809–0.852 | |

| Mean inter-item correlation | 0.657 | 0.463 | 0.694 | |

| Inter-rater reliability (ICC2,1) | 0.974 | 0.928 | 0.979 | 0.964 |

| Kappa coefficient (κ) | ||||

| 1: F1a/F2a/F3a* | 0.927 | 0.864 | 0.855 | |

| 2: F1b/F2b/F3b* | 0.923 | 0.837 | 0.866 | |

| 3: F1c/F2c/F3c* | 0.898 | 0.877 | 0.841 | |

| Concurrent validity† | ||||

| Spearman correlation coefficient | 0.852 | 0.764 | 0.685 | 0.894 |

SD standard deviation, ICC2,1 intraclass correlation coefficient based on two-way random effects.

†Compare with BI total score.

–No value.

*F1a represents the bladder and bowel, F1b represents the feeding, F1c represents the entertainment, F2a represents the toileting, F2b represents the grooming and bathing, F2c represents the housework, F3a represents the exercise in the community mobility, and F3b represents the shopping. F3c represents the social participation.

Comparison of the question burden and time consumption between CAT-LS and BI

The CAT-LS model required fewer questions to be answered than the complete BI questionnaire, with four questions for the bedridden group and five each for the domestic and community groups. This represents a 60% and 50% decrease in question burden, respectively. The time consumption of the CAT-LS was significantly lower than that of the BI, with a median difference ranging from 9.6 to 23.7 s (Table 10).

Table 10.

Time consumption comparison of CAT-LS and BI.

| CAT-LS (seconds) | BI (seconds) | Decrease of questions/median difference | Test | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Number of questions required | 4/5 | 10 | 60%/50% | ||||

| Bedridden group | 25.1 | 18.7 | 37.6 | 23.6 | 12.5 | t.test | < 0.05 |

| Domestic group | 32.5 | 21.4 | 56.2 | 20.5 | 23.7 | t.test | < 0.05 |

| Community group | 19.6 | 16.3 | 29.2 | 12.1 | 9.6 | t.test | < 0.05 |

SD standard deviation.

P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the CAT-LS exhibits robust concurrent validity and interrater reliability. The CAT-LS encompasses only 4 out of the 5 evaluation items, reducing the assessment workload by 40% required by BI. Additionally, administering the CAT-LS takes significantly less time, with an average duration of 19.6–25.1 s, which is merely half of the time required for the BI measure. These results show the reliability, validity, and efficiency of the CAT-LS in hospitalized stroke survivors. Healthcare practitioners can confidently employ the CAT-LS to alleviate the assessment burden faced by both patients and administrators.

The CAT-LS effectively categorized 7151 patients into three groups, namely, bedridden, domestic, and community, based on their ADL levels with significantly varying BI total scores, which is similar to our previous findings using LS in neurological diseases14. The CAT-LS decision-tree scoring method matched stroke survivors’ levels of ADL. A large proportion (56.2%) of stroke survivors were classified as bedridden groups, which can be attributed to these participants being hospitalized with poor ADL scores compared to community stroke survivors.

Significant differences were observed in the median scores for each BI item across the three CAT-LS groups. Specifically, the bedridden group exhibited lower scores in several items compared to the domestic group, including bathing, grooming, dressing, toileting, bed/chair transfer, walking, and climbing stairs. Notably, in the bedridden group, BI item scores for bathing and climbing stairs were consistently low at approximately 0 points. In contrast, the community group consistently achieved the highest scores, particularly in domains such as feeding, grooming, dressing, bowel management, bladder management, toileting, and bed/chair transfers with perfect scores of 10 or 15. These findings suggest that without directly querying patients about their ability to perform tasks such as bathing, walking, climbing stairs, or using the toilet, we can reasonably infer that stroke survivors in the bedridden group would likely require the most assistance in these specific activities. Conversely, stroke survivors in the community group did not feel necessary to assess their ability level concerning feeding, bladder management, and bowel management indicating self-sufficiency in these areas without external assistance. In the CAT-LS evaluation results, the score difference of each BI item among the three CAT-LS groups precisely shows that it is unnecessary to evaluate all BI items, as the approximate level of help of each BI item of the evaluation object can be known.

The results of the CAT-LS decision-tree scoring model were based on the individual transfer ability and mobility scope, and classified individuals into three groups. Once the participants were classified into one of the three groups, only the items in that group were evaluated. A decision tree is a versatile predictive model that learns based on observations and logic34. It represents and classifies events using a rule-based forecasting system34. The CAT algorithm selected the most appropriate question to be asked next using information from questions already answered18,35, and each subscale item was evaluated based on group classification.

Our results indicate that the CAT-LS demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties for evaluating ADL in stroke survivors. Concurrent validity was assessed by calculating Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the CAT-LS and BI, a commonly used ADL assessment tool27. The correlation between CAT-LS grades and total BI score was 0.964 in hospitalized stroke survivors, indicating good concurrent validity, similar to that of LS used in other diseases11,26. Here, the large dataset used is a critical advantage that supports the statistical analysis performed. The linear regression analysis of the CAT-LS results and BI scores showed an ideal correlation coefficient for standard validity (R2 = 0.874). The high R2 values indicated that the CAT-LS results were closely associated with the model’s predictions of the total BI score in stroke survivors. These findings indicate that the scores of the CAT-LS are likely to be strongly correlated with those of the BI. If so, the scores of the CAT-LS items about BADL and those of the BI are comparable and even interchangeable using linear transformation.

The CAT-LS grades had floor and ceiling effects of < 20%, indicating that the tool was sensitive to changes in ADL ability across the full range of scores. The CAT-LS grades demonstrated floor and ceiling effects of 19.2/11.7, which fell below the recommended level of 20%, as suggested in previous studies36,37. The internal consistency of three CAT-LS groups, as measured using Cronbach’s α, was 0.857, 0.803, and 0.912, respectively. Cronbach’s α between 0.70 and 0.95 indicates good internal consistency38. Therefore, the internal consistency of all three groups was deemed acceptable and comparable to that of the traditional version of the LS11. Interrater reliability was high, as evidenced by the ICC2,1 values ranging from 0.928 to 0.979, as well as the kappa values falling within the range of 0.898–0.927, 0.837–0.877, and 0.841–0.866 for the bedridden, domestic, and community groups, respectively. The above results suggest that the CAT-LS showed good consistency with the BI in classifying the ADL groups and high interrater reliability when used in stroke survivors.

With approximately 2.5 million new stroke cases yearly, the number of patients requiring ADL assessment and assistance is expected to increase exponentially in China39. The inner logic of the programming makes the CAT-LS evaluation process easy to implement and reduces the administrative burden on both clinicians and patients. The decision tree used in CAT-LS reduces the number of questions required by 50% or 60% compared with BI, promoting measurement efficiency40. CAT-LS can streamline the ADL assessment process and alleviate the burden on healthcare professionals. Therefore, CAT-LS has great potential for use by clinicians and patients in time-pressed clinical settings to effectively manage stroke survivors.

Study limitations

Although our findings are positive, this study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional cohort study; we did not test the response validity in a clinical setting. Therefore, the sensitivity of the CAT-LS to changes over time should be further explored; and it could be combined with a longitudinal study to gain insight into the responsiveness of the CAT-LS to changes in ADLs over time. Second, the questionnaire is currently limited to the Chinese population, which may limit the generalisability of the study. However, we already planned to validate the validity of the CAT-LS in multiple languages, carrying out validation in different populations, languages, and settings to ensure its applicability. Third, the stroke survivors’ data were from hospitals; participants in the acute stage of stroke are unlikely to perform IADL (e.g., washing clothes, housework, or shopping), which could have introduced information bias. Therefore, the generalizability of our results may be limited. In terms of methodological constraints, using structural equation modeling (SEM), particularly the non-parametric approach Partial Least Squares (PLS)41, is indeed a suitable method for analyzing correlations between latent variables such as CAT-LS and BI. This is especially relevant when the sample is not a random list of patients. PLS-SEM is well-suited for small sample sizes, non-normal data, and complex relationships between variables.

Conclusions

The CAT-LS demonstrated strong performance as a tool for evaluating the ADL of stroke survivors, with high concurrent validity and interrater reliability. Notably, the CAT-LS using the tree-decision method can alleviate the assessment burden on patients and examiners by reducing the number of items. The assessment results could be incorporated into electronic medical records to further improve efficiency in patient management in the clinic setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study and all the medical staff who participated in the data collection.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- BADL

Basic activities of daily living

- BI

Barthel index

- CAT-LS

Computer-adaptive test-Longshi scale

- CAT

Computerized adaptive testing

- IADL

Instrumental activities of daily living

- ICC2,1

Intraclass correlation coefficient based on a two-way random effect

- ICF

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

- LS

Longshi scale

- QRL

Quicker recovery line

Author contributions

ZJ, ZFB, and WYL contributed to the conception and design of the work; LF, WL, and XKW contributed to the data acquisition; ZJ contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the work; and CML, ZMC, LJJ, and WYL contributed to revising the work for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be countable for all aspects of the work. All inpatients or their proxies consented to publish this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Code: 2020YFC2008700) and a grant from the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZSM202111010).

Data availability

All the summarized and analysed data during this study are included in this published article; the original data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jing Zhou and Fubing Zha.

References

- 1.Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, Deruyter F, Eng JJ, Fisher B, Harvey RL, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: A guideline for healthcare professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:e98–e169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carod-Artal FJ, González-Gutiérrez JL, Herrero JA, Horan T, De Seijas EV. Functional recovery and instrumental activities of daily living: Follow-up 1-year after treatment in a stroke unit. Brain Inj. 2002;16:207–216. doi: 10.1080/02699050110103337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edemekong, P. F. et al. Activities of daily living. In Starters (2022).

- 4.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1983;31:721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mlinac ME, Feng MC. Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016;31:506–516. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong DK. Measurement of instrumental activities of daily living in stroke. Stroke. 1995;26:1119–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.26.6.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorrentino G, Sale P, Solaro C, Rabini A, Cerri CG, Ferriero G. Clinical measurement tools to assess trunk performance after stroke: A systematic review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018;54:772–784. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.18.05178-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md. State Med. J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pashmdarfard M, Azad A. Assessment tools to evaluate activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in older adults: A systematic review. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 2020;34:33. doi: 10.34171/mjiri.34.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Li S, Pan W, Xiao P, Zhang J, Wang QM, Luo X, Wang Y. Evaluation of the disability assessment Longshi scale: A multicenter study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020;48:300060520934299. doi: 10.1177/0300060520934299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Guo S, Zheng J, Wang QM, Zhang Y. User testing of the psychometric properties of pictorial-based disability assessment Longshi scale by healthcare professionals and non-professionals: A Chinese study in Shenzhen. Clin. Rehabil. 2019;33:1479–1491. doi: 10.1177/0269215519846543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Bickenbach J, Kostanjsek N, Schneider M. The International Classification of functioning, disability and health: A new tool for understanding disability and health. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003;25:565–571. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Liu F, Wong J, Xue K, Zhou M, Long J, Qu S, Li J, Yang Q, Wang Y. Reliability of Longshi scale with remote assessment of smartphone video calls for stroke patients' activities of daily living. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023;32:106950. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J, Liu X, Wan L, Gao Y, Huang M, Zha F, Long J, Li D, Nie G, Wang Y. A novel Longshi scale measured activity of daily living disability in elderly patients affected by neurological diseases: A multi-center cross-sectional study in China. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:348. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02296-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong F, Liu X, Zhou M, Wang C, Liu Q, Li J, Wang Y. Validation of the Longshi scale in assessment of function in patients from different economic, educational and regional backgrounds in China. Clin. Rehabil. 2023;37:1552. doi: 10.1177/02692155231174689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin GH, Huang YJ, Chou YT, Chiang HY, Hsieh CL. Computerized adaptive testing system of functional assessment of stroke. J. Vis. Exp. 2019;143:e58137. doi: 10.3791/58137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linden WJ, van der Linden WJ, Glas CA. Computerized Adaptive Testing: Theory and Practice. Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin GH, Huang YJ, Lee YC, Lee SC, Chou CY, Hsieh CL. Development of a computerized adaptive testing system for assessing 5 functions in patients with stroke: A simulation and validation study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019;100:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien TW, Wu HM, Wang WC, Castillo RV, Chou W. Reduction in patient burdens with graphical computerized adaptive testing on the ADL scale: Tool development and simulation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2009;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin GH, Huang YJ, Lee SC, Huang SL, Hsieh CL. Development of a computerized adaptive testing system of the functional assessment of stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018;99:676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Gao Y, Zhao J, Zhou M, Wan L, Nie G, Wang Y. Reliability of pictorial Longshi scale for informal caregivers to evaluate the functional independence and disability. Nurs. Open. 2023;10:1852–1862. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokotailo RA, Hill MD. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using international classification of diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke. 2005;36:1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174293.17959.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Zhou M, Zhao J, Gao Y, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wan L, Nie G, Wang Y. Functional independence and disability evaluation in stroke patients: Optimal cutoff scores for a pictorial-based Longshi scale, Barthel index, and modified Rankin scale. Front. Neurol. 2022;13:710852. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.710852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Y, Zhao J, Liu X, Xie X, Wang Y. Content comparison of long-term care instruments based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:146. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03824-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilanda: Quicker Recovery Line (2022).

- 26.Gao Y, Wang Y, Li D, Zhao J, Dong Z, Zhou J, Fu G, Zhang J. Disability assessment in stroke: Relationship among the pictorial-based Longshi scale, the Barthel index, and the modified Rankin scale. Clin. Rehabil. 2021;35:606–613. doi: 10.1177/0269215520975922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taghizadeh G, Martinez-Martin P, Meimandi M, Habibi SAH, Jamali S, Dehmiyani A, Rostami S, Mahmuodi A, Mehdizadeh M, Fereshtehnejad SM. Barthel index and modified Rankin scale: Psychometric properties during medication phases in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020;63:500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakharkar P, Ansari N. Application of exploratory factor analysis and item response theory to validate NHANES ADL scale in patients reporting rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacy. 2022;10:138. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy10060138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou M, Liu X, Zha F, Liu F, Zhou J, Huang M, Luo W, Li W, Chen Y, Qu S, et al. Stroke outcome assessment: Optimizing cutoff scores for the Longshi scale, modified Rankin scale and Barthel index. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0251103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018;126:1763–1768. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsueh I-P, Chen J-H, Wang C-H, Hou W-H, Hsieh C-L. Development of a computerized adaptive test for assessing activities of daily living in outpatients with stroke. Phys. Ther. 2013;93:681–693. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liljequist D, Elfving B, Skavberg Roaldsen K. Intraclass correlation—A discussion and demonstration of basic features. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al Fryan LH, Shomo MI, Alazzam MB, Rahman MA. Processing decision tree data using internet of things (IoT) and artificial intelligence technologies with special reference to medical application. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022;2022:8626234. doi: 10.1155/2022/8626234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Peute L, Scheeve T, Jaspers M. Classification and regression tree and computer adaptive testing in cardiac rehabilitation: Instrument validation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e12509. doi: 10.2196/12509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes WC, Shea JA. Performance of a new, HIV/AIDS-targeted quality of life (HAT-QoL) instrument in asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Qual. Life Res. 1997;6:561–571. doi: 10.1023/A:1018464200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon S, Hartzema AG, Duncan PW, Min-Lai S. Disability measures in stroke: Relationship among the Barthel index, the functional independence measure, and the modified Rankin scale. Stroke. 2004;35:918–923. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000119385.56094.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu S, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Z, Wang W, Anderson CS, Sandercock P, Wang Y, Huang Y, Cui L, et al. Stroke in China: Advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:394–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Li LSW. Development of rehabilitation in China. Phys Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2019;30:769–773. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciavolino E, Aria M, Cheah J-H, Roldán JL. A tale of PLS structural equation modelling: Episode I—A bibliometrix citation analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022;164:1323–1348. doi: 10.1007/s11205-022-02994-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the summarized and analysed data during this study are included in this published article; the original data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.