Abstract

Importance: There are currently 55 million adults living with declining functional cognition—altered perception, thoughts, mood, or behavior—as the result of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related neurocognitive disorders (NCDs). These changes affect functional performance and meaningful engagement in occupations. Given the growth in demand for services, occupational therapy practitioners benefit from consolidated evidence of effective interventions to support adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners.

Objective: These Practice Guidelines outline effective occupational therapy interventions for adults living with AD and related NCDs and interventions to support their care partners.

Method: We synthesized the clinical recommendations from a review of recent systematic reviews.

Results: Twelve systematic reviews published between 2018 and 2021 served as the foundation for the practice recommendations.

Conclusion and Recommendations: Reminiscence, exercise, nonpharmacological behavioral interventions, cognitive therapy, sensory interventions, and care partner education and training were found to be most effective to support adults living with AD and related NCDs.

Plain-Language Summary: These Practice Guidelines provide strong and moderate evidence for occupational therapy practitioners to support adults living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related neurocognitive disorders (NCDs) and their care partners. They provide specific guidance for addressing the decline in cognition, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, and pain experience of adults living with AD and related NCDs. The guidelines also describe interventions to support care partners. With support from the evidence, occupational therapy practitioners are better equipped to address the unique needs of adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners.

These Practice Guidelines provide strong and moderate evidence for occupational therapy practitioners to support adults living with Alzheimer’s disease and related neurocognitive disorders and their care partners.

Every 3 s, another person develops dementia, which equates to 10 million new cases of dementia each year worldwide (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2023). In 2020, more than 55 million people globally were living with a form of dementia; this number is expected to grow to 139 million by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2023). In the United States alone, an estimated 6.7 million adults live with dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023); this number is projected to grow to 13.9 million by 2060 (Matthews et al., 2018). The cost to manage individuals living with the condition globally currently costs $1.3 trillion (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2023). Most people know someone who has dementia or has lost a friend or family member to the condition.

Dementia is a general term given to a collection of conditions of the brain that negatively affect memory, behavior, emotion, and the ability to think clearly and make decisions. It is progressive, and it currently has no cure (Alzheimer’s Association, n.d.-b). The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which makes up 60% to 80% of all dementia cases (Alzheimer’s Association, n.d.-b). Other related neurocognitive disorders (NCDs) include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), among others. It is important to distinguish the symptoms of dementia from those of MCI. People with MCI may experience changes in memory, planning, decision-making, or other cognitive functions; however, these changes are not severe enough to limit the performance of most daily activities, and MCI does not necessarily lead to dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, n.d.-a).

Despite common belief, dementia is not a normal part of aging (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023). Adults living with AD and related NCDs experience a decline in memory and thinking skills. They have a difficult time retaining new information and making decisions. Challenges with memory and decision-making may limit participation in work, volunteer, household management, and health management activities. As the condition worsens, adults living with AD and related NCDs may become more disoriented or confused, experience extreme mood and sensory changes, and have more extreme memory loss. This can lead to behaviors such as irritability, wandering, restlessness, anxiety, depression, or disinterest that are difficult to manage. Adults with AD may also experience sleep disturbances and find talking, walking, and eating challenging. These changes limit participation in meaningful occupations. For example, an adult who wanders during the night may be exhausted during daytime hours and disengage from leisure occupations. In addition, changes in sensory perception, limited emotion regulation, and pain may decrease their ability to engage in meaningful occupations with family and friends.

As dementia progresses, adults require assistance from a care partner for activities such as bathing, meal preparation, managing finances, shopping, and driving. Over time, as the responsibilities in caring for someone with dementia increase, the care partner’s quality of life may decrease. Care partners of adults living with AD and related NCDs have worse health outcomes than their peers (Larsen et al., 2018; National Alliance for Caregiving, 2017). It is important for care partners to have access to support services and resources that enhance their ability to provide care.

Occupational therapy practitioners are positioned throughout the health care system to address the complex needs of adults living with AD and related NCDs as well as those of their paid and unpaid care partners. Occupational therapists are unique in that they consider personal factors and performance skills as well as environmental factors when developing interventions (American Occupational Therapy Association [AOTA], 2020). Occupational therapy practitioners are skilled at not only understanding the functional limitations of individuals experiencing NCDs but also educating and training care partners to decrease their own risk factors that develop because of their role as care partners; this allows them to avoid burnout and continue to provide necessary care.

A systematic review informed these Practice Guidelines and addressed common challenges for adults living with AD and related NCDs as well as interventions that specifically pertain to care partners. This builds on previous Practice Guidelines and systematic reviews on the topic (Jensen & Padilla, 2017; Piersol et al., 2017; Piersol & Jensen, 2017; Smallfield & Heckenlaible, 2017). The findings of those reviews remain relevant and applicable; specifically, they found strong evidence supporting errorless learning to improve task completion and exercise interventions to improve performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and sleep (Smallfield & Heckenlaible, 2017). Strong evidence also supports environments that are homelike, multisensory, or person centered as improving behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (Jensen & Padilla, 2017). Strong evidence also supports a range of single-component and multicomponent care partner interventions (Piersol et al., 2017). There are many other important findings and recommendations in those reviews that are not repeated here. Readers are encouraged to refer to this important body of literature because the systematic review for these Practice Guidelines does not include all of these recommendations. Given the growth in literature on AD and related NCDs, there is now sufficient evidence to warrant a systematic review of systematic reviews. Three common challenges for adults with AD and related NCDs that had a sufficient body of literature included (1) cognition (Metzger et al., 2023), (2) pain (Green et al., 2023), and (3) behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD; Smallfield et al., 2023). Interventions supporting care partners have also been included in their own systematic review brief (Rhodus et al., 2023).

Systematic Review Question

These Practice Guidelines are based on the following question: What is the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy practice to improve performance and participation for people living with AD and other related NCDs and their care partners?

Goals of These Practice Guidelines

Through these Practice Guidelines, AOTA aims to help occupational therapy practitioners, as well as the people who manage, reimburse, or set policy regarding occupational therapy services, understand occupational therapy’s contribution in providing services to adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners. These guidelines can also serve as a reference for health care professionals, health care facility managers, education professionals, education and health care regulators, third-party payers, managed care organizations, and those who conduct research to advance care of adults living with AD and related NCDs.

These Practice Guidelines were commissioned, edited, and endorsed by AOTA without external funding being sought or obtained. They were financially supported entirely by AOTA and were developed without any involvement of industry. All authors of these Practice Guidelines completed conflict-of-interest disclosure forms, with no conflicts noted. AOTA reviews practice guidelines, and updates them as needed, every 5 yr to keep recommendations on each topic current according to criteria established by the ECRI Guidelines Trust® (2020). Guideline topics are evaluated by a multidisciplinary advisory group consisting of AOTA members, nonmember content experts, and external stakeholders. These Practice Guidelines were reviewed and revised on the basis of feedback from a group of content experts on adults living with AD and NCDs that included practitioners, researchers, educators, and policy experts. Reviewers who agreed to be identified are listed in the Acknowledgments.

These Practice Guidelines report the findings from a systematic review of published scientific research on a focused topic-specific question. The systematic review was conducted according to the Cochrane Collaboration methodology (Higgins et al., 2019), and the findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for conducting systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2009). The protocol and question were developed with input from a multidisciplinary advisory group that also included consumers and information end-users. A medical research librarian conducted searches of the literature, and review teams evaluated the search results and synthesized the findings (the Appendix provides an overview of the systematic review methods and findings). Interventions that were described in sources other than the published literature and that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the review.

Occupational therapy practitioners should not consider these Practice Guidelines to be a source of comprehensive information about adults living with AD and related NCDs or about application of the occupational therapy process. The occupational therapist makes the ultimate clinical judgment regarding the appropriateness of a given intervention in light of a specific client’s or group’s circumstances, needs, and response to intervention, as well as the evidence available to support the intervention. This may be done in collaboration with occupational therapy assistants involved in the service delivery. Examples of how evidence can inform practice with adults living with AD and related NCDs are included in the Case Studies and Evigraphs section.

AOTA supported the systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy for adults living with AD and related NCDs as part of its Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Program. AOTA’s EBP Program is based on the principle that the evidence-based practice of occupational therapy relies on the integration of information from three sources: (1) clinical experience and reasoning, (2) preferences of clients and their families, and (3) findings from the best available research. The systematic review briefs and these Practice Guidelines report the findings from the best available research.

Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations for Occupational Therapy Interventions for Adults Living With AD and Related NCDs

AD and Related NCDs

Clinical recommendations are the final phase of the synthesis of systematic review findings. The findings for each systematic review question are graded in terms of how confident a practitioner can feel that using the interventions presented in the evidence will improve the outcomes of interest to their clients. The grade is based on the specificity of the intervention, number of studies supporting the intervention, levels of evidence of the studies, quality of the studies, and significance of the study findings. Interventions included in the clinical recommendations are specific to a population, and the articles that describe them provide sufficient detail for practitioners to understand the intervention and the outcomes of interest.

Describing the strength of clinical recommendations is an important part of communicating an intervention’s efficacy to practitioners and other users. The recommendations for these Practice Guidelines were evaluated and finalized by AOTA staff, the AOTA research methodologist, and the systematic review briefs and Practice Guidelines authors. AOTA uses the grading methodology provided by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2018) for clinical recommendations. The clinical recommendations pertaining to each review, along with the studies’ level of evidence and supporting details, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations for Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational Therapy Practice to Improve Performance and Participation for Individuals With AD and Related NCDs and Their Care Partners

| Grade/Evidence Level | Citation | Intervention Details |

|---|---|---|

| Interventions to Improve Cognitive Function for Individuals With Dementia | ||

| Cognitive Therapy Interventions | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing individual or group cognitive-oriented approaches to improve cognitive function in individuals with dementia, in addition to another intervention, such as standard OT or medication (3 wk–6 mo, 10–40-min sessions, 2–6×/wk) | |

| 1a 7 RCTs |

Ham et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 453 people diagnosed with AD, majority in their 70s Setting: Home, community, hospital, dementia center, others not described Intervention: Combination of OT-based intervention combined with other treatment modalities (5), or an intervention using only OT that included a cognitive-oriented approach (2) Delivery method: group (3), individual (3), mixed (1) Dose: 1–5 hr, 1–3×/wk, 8–24 wk (most effective programs were >1×/wk for >16 wk) Improvement: A significant improvement in cognition was noted for all interventions. |

| 1a 11 RCTs, 6 included in the meta-analysis |

Duan et al. (2018) |

Population: N = 682 adults with AD (no MCI, no non-AD; no way to determine number of participants in the meta-analysis), information from 285 adults from 4 RCTs is reported here. M age = 74–84 yr Setting: Not reported Intervention: Combination of psychosocial intervention and medication: cognitive stimulation and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, mindfulness-based Alzheimer’s stimulation and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; cognitive training and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor Delivery method: Group, individual Dose: 10 wk–2 yr, details not reported Improvement: Cognitive therapy + acetylcholinesterase inhibitor was the best psychosocial/drug combined intervention for improving cognitive symptoms. |

| Exercise Interventions | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider the use of individual or group exercise interventions—specifically, the use of walking programs and exercise paired with memory games and music therapy (15–30 min/day, for 6–12 mo, no further details provided)—to improve cognitive function in individuals with dementia. | |

| 1a 10 RCTs, 6 included in the meta-analysis |

Duan et al. (2018) |

Population: N = 682 adults with AD (no MCI, no non-AD), M age = 74–84 yr (no way to determine number of participants in meta-analysis); information from 182 adults from 2 RCTs is reported here. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Home-based exercise (HE; 1 study, n = 161), group exercise (1 study, n = 161), walking programs (WP; 1 study, n = 21) Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: 6 mo–1 yr, no further details provided Improvement: The WP intervention and HE were significantly better than the control condition (usual care or drug intervention) at improving cognition. The WP intervention was more effective compared with other treatments in the study, including the HE program. |

| 1a 14 RCTs |

Hui et al. (2021) |

Population: 1,161 participants, ns = 21–189 older adults, age 62+ yr; individuals with moderate to severe dementia Setting: Home Intervention: Multisensory stimulation intervention (6), multicomponent interventions (5), exercise programs (2), reminiscence program (1) Delivery method: Caregiver and health care provider delivered, individual Dose: 15 min/day for 15 mo (cycling), 30 min/day for 6 mo (walking) Improvement: Significant improvement in cognitive function was noted in interventions that included aerobic exercise, memory games, and music therapy. The exercise program groups showed a statistically significant improvement in cognitive function (control group showed a decline). |

| Music Interventions | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider including the use of music interventions (MIs) paired with movement, individually or in a group, to improve cognitive function in individuals with dementia (1–5×/wk, 10–120 min, 1–40 wk). | |

| 1a 36 RCTs, 30 included in the meta-analysis |

K. H. Lee et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 3,443 participants total, n = 2,551 included in the meta-analysis. M age = 69.1–94.9 yr; proportion of females with any form of dementia = 40%–100%. Of 30 RCTs, 11 were music intervention RCTs (N = 386); of those 11, 6 RCTs (n = 104) were looking at cognition outcomes. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Music intervention; participants completed movements while accompanied by music Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: 10–90 min for 1–21 sessions, no further details provided Improvement: Significantly improved cognitive function was noted in the individual and group conditions. |

| 1a 21 RCTs, 9 included in the meta-analysis |

Dorris et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 1,472 adults total, with n = 495 in the meta-analysis; M age = 68.93–87.93 yr; majority had mild to moderate dementia Setting: Long-term care facilities, day centers, specialty outpatient units, and community Intervention: Active music-making, defined as “physically participating in music.” 17 studies used re-creating music by singing/playing instruments, 10 used improvisation, 6 used movement, 1 used imagery, 1 used breathing entrainment, and 2 had other characteristics: 1 created attention exercises in which participants reacted to a stimulus, such as clapping when hearing a drum but refraining when hearing a drum preceded by a cymbal, and 1 comprised dual-task training. Delivery method: Not reported Dose: 4–40 wk, sessions ranged from 30 min to 2 hr in length and took place 1–5×/wk. Improvement: Significantly improved cognitive function was noted in all groups. |

| Reminiscence Interventions | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing individual or group reminiscence therapy to improve cognitive function in individuals with dementia (1–12 wk, 10–60 min long, over 1–12 wk). | |

| 1a 36 RCTs, 30 included in the meta-analysis |

K. H. Lee et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 3,443 participants total, with n = 2,551 included in the meta-analysis; M age = 69.1–94.9 yr; proportion of female participants with any form of dementia = 40%–100%. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Reminiscence therapy Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: 10–60 min/wk for 1–21 sessions Improvement: Significantly improved cognition was observed in both the individual and group conditions. |

| 1a 11 RCTs, 6 articles included in the meta-analysis |

Duan et al. (2018) |

Population: N = 682 people with AD (no MCI, no non-AD; no way to determine number of participants in the meta-analysis); M age = 74–84 yr, information from 2 reminiscence therapy studies (n = 144) is reported here. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Reminiscence therapy Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: 4–12 wk Improvement: Significantly improved cognition was observed in both the individual and group conditions. |

| Dance Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider including group dance training interventions to improve global cognitive function for individuals with MCI (12–40 wk, 1–3 sessions/wk for 35–60 min). | |

| 1a 8 RCTs, 7 included in the meta-analysis |

Wu et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 455, range = 31–201 across the 8 studies, participant M age = 65–81 yr. All had MCI. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Dance training Delivery method: Group, in person Dose: 12–40 wk, 1–3 sessions/wk for 35–60 min Improvement: Dance interventions significantly improved global cognition, memory, visuospatial, and language, in older adults with MCI. |

| Interventions to Improve Cognitive Function for Individuals With MCI | ||

| Cognitive Therapy Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing individual or group cognitive-oriented approaches, in addition to another intervention, such as standard OT or medication, to improve cognitive function in individuals with MCI (2–20 mo and >10 sessions). | |

| 1a 10 RCTs, 5 included in the meta-analysis |

Chow et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 966 total participants with MCI, n = 294 included in the meta-analysis, M age = 73 yr Setting: Not reported Intervention: Psychosocial interventions, including behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and CBT. Interventions to enhance memory included behavior modification and activation, memory training, visual imagery, storytelling, memory aids, journaling, and exercise. Delivery method: Group (7), individual (3) Dose: 2–20 mo. Interventions addressing memory that were longer in duration (>2 mo), had more therapeutic encounters (>10), and were delivered individually had larger effect sizes. Improvement: Significant improvements in memory were noted in both the individual and group conditions. |

| Interventions Addressing Depressive Symptoms in Individuals With Dementia | ||

| Reminiscence Therapy | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing reminiscence therapy interventions, individually or in a group, to reduce depressive symptoms among individuals with dementia (10–90 min; 1–21 sessions/wk, no other details reported). | |

| 1a SR 16 RCTs |

Park et al. (2019) |

Population: N = 1,763 adults, M age = 85 yr; all types of dementia; n = 895 for studies specific to outcomes of depressive symptoms Setting: Not reported Intervention: Reminiscence therapy Delivery method: Individual (5) and group (18) Dose: Up to 12 sessions; no further details provided Improvement: Depression was significantly reduced in both the individual and group conditions. |

| 1a SR 10 RCTs, 6 included in the meta-analysis |

K. H. Lee et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 1,271 participants specific to reminiscence with any form of dementia with an emphasis on AD; M age = 69.1–94.9 yr; the proportion of female participants = 40%–100% Setting: Not reported Intervention: Reminiscence therapy Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: Duration = 10–90 min; frequency = 1–21 sessions/wk Improvement: Depression was significantly improved in both a group or individual setting. |

| Pharmacological Versus Nonpharmacological Behavioral Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing many nondrug behavioral interventions to manage depression in individuals with dementia diagnosed with depression (dose not reported). | |

| 1a 256 RCTs, 213 included in the meta-analysis |

Watt et al. (2021) |

Participants: N = 28,483 adults with dementia; n = 25,177 adults with dementia without MDD experiencing depressive symptoms; n = 1,829 adults with dementia + major depression. Women made up at least 50% of the study sample in most studies. M age in most studies = ≥70 yr. Setting: Community and clinic Intervention: Pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions Delivery method: Not reported Dose: Not reported Improvement: Overall, nonpharmacological interventions were as effective, or more effective, than pharmacological interventions for reducing symptoms of depression in people with dementia without a diagnosis of MDD: massage + touch therapy and cognitive stimulation + social interaction. Nondrug interventions that were significantly better than usual care in addressing depression were animal therapy, cognitive stimulation, exercise, massage + touch, reminiscence, multidisciplinary care, OT nonspecified, exercise + cognitive stimulation + social interaction, psychotherapy + reminiscence + environmental modification. No drug alone was better than usual care. |

| MIs | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing MIs (i.e., listening, singing, or songwriting), individually or in a group setting, to reduce depression among individuals with dementia (1–21 sessions/wk, 30–60 min, no other details reported). | |

| 1a 36 RCTs, 3 included in the meta-analysis |

K. H. Lee et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 792 adults with dementia, with an emphasis on AD, were included in studies specific to MI for depression-related outcomes; for all articles included in the SR, M age = 69.1–94.9 yr; the proportion of female participants = 40%–100%. Setting: Not reported Intervention: MI (listening, singing, or songwriting) Delivery method: Individual or group Dose: Duration = 30–60 min; frequency = 1–21 sessions/wk Improvement: MI (listening, singing, or songwriting) had a significant effect on reducing depression. |

| Interventions to Address Depressive Symptoms in Individuals With MCI | ||

| Exercise Intervention | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider supporting the use of physical exercise to reduce depression among individuals with MCI (dose not reported). | |

| 1a 22 RCTs, All included in the meta-analysis |

Xu et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 2,302 participants total with MCI; M age = 63.1–76.5 yr; proportion of female participants = 39.1%–95.5%. 8 out of 22 RCTs addressed exercise and are reported here. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Physical exercise Delivery method: Not reported Dose: Not reported Improvement: Physical exercise significantly reduced depressive symptoms. |

| Cognitive-Based Intervention | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing cognitive-based interventions to reduce depressive symptoms among individuals with MCI (dose not reported). | |

| 1a 22 RCTs and a network analysis |

Xu et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 2,302 adults with MCI; M age = 63.1–76.5 yr; proportion of female participants = 39.1%–95.5%. Setting: Not reported Intervention: Cognitive based Delivery method: Not reported Dose: Not reported Improvement: Cognitive-based interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms. |

| CBT to Address Anxiety in Individuals With Dementia | ||

| CBT Intervention | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing one-on-one CBT intervention to reduce anxiety among individuals with dementia (10 weekly 60-min sessions or 12 sessions in the first 3 mo. with up to 8 telephone booster appointments during Months 3–6). | |

| 1a 16 RCTs |

Noone et al. (2019) |

Population: N = 82 participants with mild to moderate dementia from 2 studies reporting on psychosocial outcomes of anxiety Setting: Not reported Intervention: CBT Delivery method: Home, telephone, face-to-face sessions, printed materials, Facebook Dose: 10 weekly 60-min sessions or 12 sessions in the first 3 mo with up to 8 telephone booster appointments during Months 3–6 Improvement: CBT reduced symptoms of anxiety in people with dementia who were anxious. There was a large effect size for CBT outcomes compared with control at the 1-wk follow-up, but these effects were not maintained at a later follow-up. |

| Nonpharmacological Interventions for Individuals With Dementia and Their Care Partners to Address General BPSD | ||

| Nonpharmacological Interventions for BPSD | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing home- or community-based nonpharmacological interventions, such as education, skill training, social support, case management, or multicomponent interventions, for informal caregivers or dyads to reduce BPSD in individuals with dementia and improve care partner reactions to BPSD (1–48 wk, no. of sessions = 4–75). | |

| 1a 31 RCTs |

Meng et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 3,501 dyads of adults with dementia and their care partners; M age of care partners who provided the primary care = 45–73 yr; age of adults with dementia not reported. Setting: Home, community Intervention: Nonpharmacological interventions such as education, skill training, social support, case management, or multicomponent for care partners or dyads. Delivery method: Not reported Dose: 1–48 wk, no. of sessions = 4–75 Improvement: Nonpharmacological interventions showed significant improvement in BPSD compared with control conditions. Tailored interventions had the highest effect size. |

| Interventions to Manage Pain Among Individuals With Dementia | ||

| Pain Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing individualized sensory stimulation interventions to groups or individuals, to reduce observed pain among individuals with all stages of dementia, in a variety of settings (e.g., LTC, community, memory clinic; 1–7×/wk, 10–120 min, 4–20 wk). | |

| 1a 8 RCTs |

Pu et al. (2019) |

Population: N = 1,861. Participants with all stages of dementia were included. Setting: LTC (6), community (1), memory clinic (1) Intervention: Sensory stimulation (6): reflexology (1), massage (2), ear acupressure (1), music (1), showering (1); physical activity (2): tai chi (1) and passive movement therapy (1) Delivery method: Group and individual Dose: 1×/wk to daily; 10–120 min/session, 4–20 wk Improvement: Significantly reduced observed pain |

| Interventions to Address Care Partner Mental Health Outcomes | ||

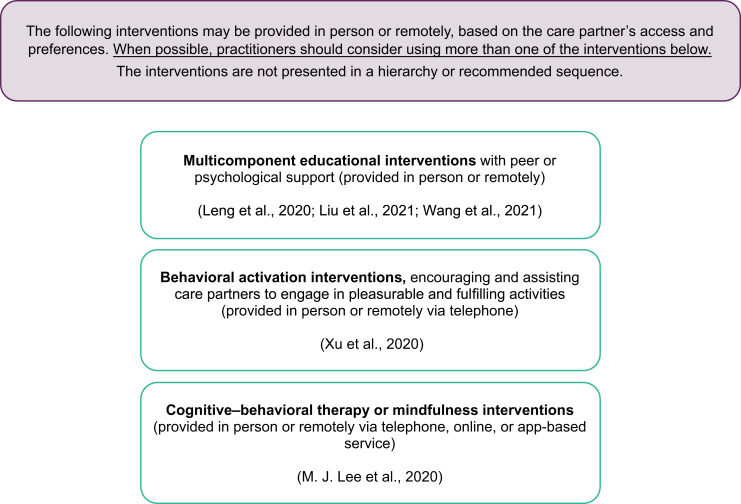

| Single- or Multicomponent Educational With Peer or Psychological Support Interventions | ||

| A: Strong | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing multicomponent educational interventions with peer or psychological support, in person or remotely, to address depression in care partners of individuals with dementia (dose not reported). | |

| 1a 6 RCTs |

Liu et al. (2021) |

Population: N = 815 care partners, M age = 58.66 yr. 4 articles reported participant gender, with 73.5% female participants Setting: Home Intervention: 2 single-component interventions using information or education and 4 multicomponent interventions, including information or education and peer support (3/4) and information or professional education and psychological support (1/4) Delivery method: Web based Dose: Not reported Improvement: Web-based interventions significantly improved depression. |

| 1a 29 RCTs |

Wang et al. (2021) |

Population: N = not reported; care partners of persons with dementia, no specification of type or stage of dementia Setting: Community Intervention: 4 studies evaluated a single-element intervention (i.e., education, training); the remaining 25 evaluated a multicomponent intervention (i.e., support group + training). Delivery method: Individual, in person, and remote Dose: Not reported Improvement: Significant improvements in care partner depression were noted. |

| 1a 65 RCTs |

Leng et al. (2020) |

Population: N = not reported, the number of participants in each study ranged from 25 to 547. Setting: Home Intervention: The intervention was a digital one delivered to family care partners via any internet-based modality, which could include either single-component interventions or multiple-component interventions. Delivery method: Individual, internet based Dose: 4 wk–12 mo Improvement: The meta-analysis showed that internet-based supportive interventions significantly reduced depressive symptoms. |

| BA Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners could consider providing BA interventions in the home setting (in person or by telephone) to reduce depression in care partners of individuals with ADRDs (5–20 wk, 15–90 min sessions). | |

| 1a 5 RCTs |

Xu et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 895 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 41 to 118; M age = 55.2–81.1 yr; the majority were female (57%). Setting: Home Intervention: BA is a way to increase pleasant leisure activities among family dementia care partners. BA assumes that clients should be assisted with the ability to engage in behaviors that they find pleasurable or fulfilling. In contrast to CBT, BA is an outside-in treatment that focuses on changing the way a person acts. Delivery method: 4 interventions were administered by telephone; the other 6 were administered through direct contact. Dose: Duration = 5–20 wk, and each session lasted 15–90 min Improvement: Depression was significantly reduced after participants received the intervention. |

| CBT or Mindfulness Interventions | ||

| B: Moderate | Recommendation: Practitioners should consider providing CBT or mindfulness interventions (in person, telephone, online, or via an app) to reduce depression in care partners of individuals with ADRDs. | |

| 1a 36 RCTs, 30 were included in the meta-analysis |

M. J. Lee et al. (2020) |

Population: N = 4,039 participants (n = 838 for CBT, n = 186 for the mindfulness intervention), with individual study samples = 16–487. M age = 62.2 yr (range = 50.5–71.1); most care partners were women (78.2%, range = 62.5%–100%) Setting: Home Intervention: (1) CBT with half the sessions focusing on BA, psychoeducational intervention, emotional support intervention, cognitive rehabilitation for care recipients, or multicomponent interventions (2) Mindfulness interventions Delivery method: Face-to-face delivery, telephone calls, web-based courses, and an application for mobile devices Dose: (1) 8 RCTs applied CBT (M no. of sessions = 10, range = 6–14), and the average intervention period was 12 wk (range = 6–20); half of these studies focused on behavioral activation. (2) 4 RCTs applied mindfulness interventions; 3 studies delivered 7–8 weekly sessions, and 1 study delivered a daily intervention for 8 wk (moderate effect). Improvement: Both the CBT and mindfulness interventions significantly reduced depression in care partners. |

Note. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ADRDs = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; BA = behavioral activation; BPSD = behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy; LTC = long-term care; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; MDD = major depressive disorder; MI = music intervention; NCD = neurocognitive disorder; OT = occupational therapy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SR = systematic review.

For the purposes of these Practice Guidelines, we report recommendations graded A, B, and D, the grades that best support clinical decision-making:

A: There is strong evidence supporting the intervention for eligible clients. Strong evidence was found that the intervention improves important outcomes and that benefits substantially outweigh harms.

B: There is moderate evidence supporting the intervention for eligible clients. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate, or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.

D: It is recommended that occupational therapy practitioners not provide the intervention to eligible clients. At least fair evidence was found that the intervention is ineffective or that harms outweigh benefits.

In this review, we did not find Grade D evidence.

These grades are reported in Table 1 and designated with green, indicating should consider if appropriate (A), or yellow, indicating could consider if appropriate (B). None of the studies included in this review reported adverse events or harms related to the interventions evaluated (D).

The complete findings from the systematic review can be found in the Systematic Review Briefs on this topic published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (Green et al., 2023; Metzger et al., 2023; Rhodus et al., 2023; Smallfield et al., 2023). As always, practitioners’ clinical decisions should be informed by the evidence presented in these Practice Guidelines in combination with their clinical experience and the client’s particular goals.

Expert Opinion Clinical Recommendations for Occupational Therapy Interventions for Adults Living With AD and Related NCDs

Expert opinion clinical recommendations were developed for important/common clinical interventions that did not reach the level of an evidence-based clinical recommendation because of a lack of research. The Practice Guidelines team analyzed the evidence and generated intervention topics that could be presented as an expert opinion recommendation. The team drafted the recommendation and provided information supporting the use of the intervention. This was then presented to an expert consensus panel (five people) comprising subject matter experts from both academic and clinical settings to review for usefulness of the recommendation, appropriate wording, quality of the support provided, and their overall level of agreement that the recommendation should be included in the Practice Guidelines. Feedback from the expert panel was used to revise the recommendation, and the revisions were sent back to the experts until a consensus was reached. Expert opinion recommendations are always considered to be at a higher risk of bias because there is a lack of research evidence to support them; they will always have a low strength of evidence. In the absence of high-quality published research, expert opinion is the best knowledge available to guide practice.

Recommendation

Practitioners may consider using promising environmental modifications, such as communal dining, ambient music, a fish tank in the dining area, and high-contrast cutlery and dishware. Overall, the most effective strategies to improve food intake and maintain body weight for adults living with AD address environmental factors rather than client factors (e.g., strength) or activity modifications.

Support

Fetherstonhaugh et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of 20 articles that examined interventions directly related to the occupations of feeding and eating. Interventions that showed the most promise were environmental modifications, including adding a fish tank (Edwards & Beck, 2002, 2013) or ambient music (McHugh et al., 2012; Richeson & Neill, 2004; Thomas & Smith, 2009) to the dining environment during mealtime. Researchers found inconsistent outcomes for increasing the amount of lighting in the dining area (Brush et al., 2002). In addition, researchers found emerging evidence for a homelike dining area; however, the findings did not reach the level of clinical significance (Altus et al., 2002; Cleary et al., 2012; McDaniel et al., 2001; Perivolaris et al., 2006). In a study of nine participants, Dunne et al. (2004) concluded that high-contrast (e.g., red) plates, cups, and cutlery increased food intake. Research does not currently support spaced retrieval (Lin et al., 2010; Wu, Lin, Su, & Wu, 2014) or skills training (Lin et al., 2010, 2011; Wu, Lin, Wu, et al., 2014), so these approaches should be used with caution and carefully monitored for effectiveness. Any approaches practitioners use should be person centered, with an emphasis on environmental modifications and clear outcomes to assess effectiveness.

Translating Clinical Recommendations Into Practice

Clinical Reasoning Considerations

Very rarely will practitioners find an evidence-based intervention that perfectly fits their clinical setting and the client’s specific needs. Occupational therapy practitioners need to consider several questions as they evaluate the research and determine whether they can use an intervention, or adapt it in a well-reasoned way, to exactly meet the client’s needs (Highfield et al., 2015):

- Exactly what intervention do I need to provide?

- What types of client outcomes am I looking for?

- Do the studies I have located provide enough detail on the intervention so that I know what to do and how to do it?

- How well do the conditions in which I will provide the intervention match those in the studies?

- What are the demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, diagnosis, comorbidities) of the participants in the research studies?

- In which setting (e.g., inpatient, home, community, school) did the studies take place?

- Do any contextual factors (e.g., resources, policies) that are different from those in the studies influence my ability to provide the intervention?

- How flexible is the intervention, and how much can I modify or adapt it?

- If my setting or client population differs from those of the studies, can I modify or adapt the intervention without changing its integrity?

- If I modify or adapt the intervention, what client characteristics (e.g., comorbidities) do I need to consider?

- Can I be proactive and plan how to modify or adapt the intervention before I start implementing it?

- Can I make minimal changes to the intervention, such as reordering the content of the sessions, or does the need for substantial changes indicate I should select another intervention?

To modify or adapt evidence-based interventions in practice, practitioners must plan and proactively think through the changes are going they need to make to fit the intervention to the client and practice setting. In addition, they must document how and why they altered the researched intervention so others in their setting know how to implement the intervention and why the changes were made. If an intervention must be adapted extensively, it may not be the right fit for the situation and is probably not right for the client or setting. If the practitioner finds that the intervention does not suit the client, they should not use that intervention. Clinical interventions should be as similar as possible to the interventions used in the research.

Case Studies and Evigraphs

The case studies in this section illustrate how occupational therapy practitioners can translate evidence from the systematic review to professional practice when collaborating with adults living with AD and related NCDs. Each case study highlights interventions that are supported by evidence and expert opinion. We provide a CPT® billing code1 (American Medical Association, 2020) for each intervention to aid translation into professional practice.

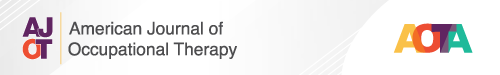

Evigraphs based on clinical recommendations were developed by the authors and AOTA staff to assist practitioners with clinical decision-making (Figures 1–3). Practitioners must consider each potential intervention in relation to the client’s individual goals, interests, habits, routines, and environment and choose interventions that strongly align with or are supportive of these factors in the context of the client’s occupational profile. It is important to note that the evigraphs in these Practice Guidelines present simplified examples of the decision-making processes occupational therapy practitioners might use to address their specific clients’ goals.

Figure 1.

Interventions to improve cognitive function for individuals living with dementia and mild cognitive impairment.

Note. See Table 1 for additional recommendations and details on each study. Occupational therapy practitioners should always consider the evidence, as well as the client’s safety, personal factors, preferences, access to resources, and interests when developing the plan of care and selecting interventions. CBT = cognitive–behavioral therapy.

Figure 2.

Interventions to improve behavioral and psychological symptoms for individuals living with dementia and mild cognitive impairment.

Note. See Table 1 for additional recommendations and details on each study. Occupational therapy practitioners should always consider the evidence, as well as the client’s safety, personal factors, preferences, access to resources, and interests when developing the plan of care and selecting interventions. OT = occupational therapy.

Figure 3.

Interventions to improve mental health outcomes for care partners of individuals living with dementia.

Note. See Table 1 for additional recommendations and details on each study. Occupational therapy practitioners should always consider the evidence, as well as the client’s safety, personal factors, preferences, access to resources, and interests when developing the plan of care and selecting interventions.

Case Study 1: Malcom

Occupational Profile

Malcom (he/him/his), age 74 yr, resides at home with his wife, Betty (she/her/hers), age 53 yr. He was diagnosed with AD at a moderate stage without mood disturbance. Malcom is a retired librarian who used to enjoy traveling in an RV with his wife and square dancing at the local community center. He was diagnosed with AD 3 yr ago, and his medical history includes primary generalized osteoarthritis and hypertension.

Malcom and Betty have lived in the same in single-family home for 32 yr. His environmental supports include an involved family, most significantly their daughter, who lives 5 min away and provides respite for Betty 2–3×/wk while Betty runs errands. Their daughter has voiced concerns with the amount of assistance her dad needs and worries about the strain on her mother. She has asked her mother if they should consider finding a nursing home or paid caregivers for him.

According to Betty, Malcom is having trouble getting onto and off the toilet because of weakness, and he recently sustained a fall, resulting in a brief emergency room visit, but he did not have a serious injury. He now requires increased assistance from Betty for initiating and completing morning dressing tasks. Betty reports it can take him over 1 hr to get out of bed when prompted because of decreased initiation and poor volition. Out of frustration, Betty usually ends up dressing Malcom to avoid his angry outbursts. Betty reports their relationship is strained because of the increased time and assistance for ADL tasks, and she expresses feeling depressed. Malcom’s primary care physician referred him to home health occupational therapy at his last checkup after the fall.

Occupational Therapy Initial Evaluation and Findings

A sample of assessments an occupational therapist might complete during the initial evaluation is included in Table 2. A home health occupational therapist completed the evaluation with the Occupational Therapy Profile Template (AOTA, 2020) and the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2019) to start the plan of care for Malcom. Malcom’s goals were as follows:

Long-Term Goal 1: Malcom will demonstrate functional transfers in the home environment with supervision, with use of compensatory strategies and adaptive equipment as needed, provided by trained care partner, by the sixth visit.

Short-Term Goal 1: Malcom will demonstrate safe sequencing of transfer onto and off a commode, with a trained care partner providing contact guard assist and a maximum level of verbal and visual cues, by the third visit.

Long-Term Goal 2: Malcom will complete ADL dressing tasks with minimal assist and a moderate level of verbal cues, with the use of environmental strategies provided by a trained care partner, by the sixth visit.

Short-Term Goal 2: Malcom will perform upper body dressing with moderate assist, with a care partner providing maximum cues per techniques, using environmental cues, by the second visit.

Table 2.

Occupational Therapy Initial Evaluation Findings for Malcom

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Barthel Index (Mahoney, 1965) |

|

| Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) (Reisberg, 1982) |

|

| Berg Balance Scale (Berg, 1992) |

|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Julayanont, 2013) |

|

| Observation and caregiver report |

|

Note. ADLs = activities of daily living.

Occupational Therapy Interventions

On the basis of the assessment findings, the occupational therapist anticipated that Malcom would meet the outlined goals in two sessions/wk for 3 wk, with each session lasting about 45 min. Emphasis was placed on care partner training with carryover of prescribed strategies at discharge to slow further declines in function. The occupational therapist collaborated with the speech-language pathologist on consistent cueing strategy use, comparison of cognitive evaluation results, and ensuring that the intervention did not result in a duplication of services. The interventions described in the sections that follow are examples that could be implemented by an occupational therapy practitioner (an occupational therapist or an occupational therapy assistant).

Intervention 1

To address cognitive decline that was limiting Malcom’s independence with commode transfers, the occupational therapy practitioner implemented an individualized cognitive-oriented approach with multisensory stimulation interventions (Hui et al., 2021). Visual strategies were implemented in the bathroom. A red x was placed on the floor where Malcom should stand and sit when getting onto and off of the commode. The clinician applied red tape to an existing grab bar to provide contrast from the wall, in order for him to more easily identify where to place his hand to stand up and sit down when prompted by his care partner (CPT code 97535: self-care/home management training, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 2

To address participation with morning ADLs, the therapist educated the care partner on improving arousal and attention with the use of music (K. H. Lee et al., 2020). Per the therapist’s recommendation, Betty started playing Malcom’s favorite country music in the bedroom before trying to wake him, to increase his level of alertness. This enabled Betty to spend less time trying to wake and arouse Malcom. She noted he appeared more focused, with less yelling and hitting, and he was able to follow simple commands with improved accuracy (CPT code 97535: self-care/home management training, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 3

To address the decline in functional transfers, the therapist recommended therapeutic dance intervention for at least 2×/wk for 30 min outside of skilled occupational therapy services (Hui et al., 2021). The therapist educated Malcom and Betty on the use of a seated square-dancing routine to improve cognitive functioning in its application to functional transfers. Betty initially reported having to ask her daughter for help with setting up the audiovisual guide; however, once she learned how to start it, after 2 wk of participation there was improvement in his physical ability to sequence his upper body for sit-to-stand transfers for clothing management (CPT code 97530: therapeutic activity, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 4

Care partner education and training were provided as a means to make additional progress in meeting goals for dressing and transfers. The therapist provided Betty with a multicomponent educational intervention about dementia, disease process management, cognitive– behavioral strategies, and care partner strategies as a part of a care partner group that met weekly for 2 mo (M. J. Lee et al., 2020; Leng et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Wang at al., 2021). Betty gained a better understanding of how to engage her husband in the care process, including strategies to appropriately prompt or cue him using hand-under-hand assistance, when needed, and using short verbal prompts for each step of the task, in addition to providing up to 1 min for her husband to respond to a command during functional tasks. She verbalized that it was getting easier for her to help him, thus alleviating some of the depressive symptoms she was experiencing herself. As a result of this training, Malcom was able to complete dressing and transfers with less physical assistance, allowing him to meet his ADL goals (CPT code 9X017: group caregiver training [without the patient present], face-to-face; initial 30 min).

Outcomes

After the completion of six sessions, the occupational therapist reevaluated Malcom’s progress. Betty had developed strategies and techniques to facilitate Malcom’s ability to successfully age in place. She was able to continue to implement seated-chair square-dancing classes she streamed on their television 2×/wk. His functional balance improved slightly, as indicated by an improved score on the Berg Balance Scale (Berg et al., 1992) of 41, indicating that he was at a low risk for falls. Although his score on the Barthel Index (Mahoney & Barthel, 1965) remained unchanged at discharge, he required less physical assistance for transfers and dressing, as indicated by all long-term goals being met. Betty also implemented a multisensory approach in assisting her husband in the morning by playing music and using high-contrast visual cues for transfers. She understood her husband’s strengths based on his level of impairment and was able to successfully cue him to increase his independence with ADLs and participation and functional mobility. Table 3 lists the additional discharge results. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Julayanont et al., 2013) and the Global Deterioration Scale (Reisberg et al., 1982) were not reassessed at discharge because Malcom’s cognitive functioning was not expected to change as result of the intervention.

Table 3.

Occupational Therapy Discharge Results for Malcom

| Assessment | Discharge Results |

|---|---|

| Barthel Index | Remained static at a score of 60/100; however, less physical assist was provided, but Malcom still requires the assistance of one person (verbal cues) for the areas scored. |

| Berg Balance Scale | Malcom’s score is 41/56, indicating a low fall risk. |

Malcom and Betty were then referred by their primary care physician to the Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model (CMS, 2023). After intake was completed by the care navigator, an occupational therapist, as a part of the interdisciplinary team, completed a home evaluation of both Betty and Malcom. The therapist determined Malcom had moderate complexity with a care partner and worked with the couple to develop a person-centered care plan to help Malcom maintain his gains and ensure Betty’s emotional well-being. Additional services provided through the GUIDE model include 24/7 access to a member of the care team, ongoing monitoring and support, referral and support services, care partner support, medication management, and care coordination (CMS, 2023). As a part of care partner support, Betty received respite support on a limited basis while she visited her sister for a long weekend.

Case Study 2: Maria

Occupational Profile

Maria (she/her/hers) is an 82-yr-old woman who resides in the memory care community of a skilled nursing facility (SNF). She grew up in a rural area and raised four children with her partner. She worked as a school bus driver and enjoyed knitting, watching sports, and cooking for her family. She was diagnosed with AD 5 yr ago, and her partner cared for her at home. After her partner’s death, her children were unable to manage her care as her dementia progressed to a moderately severe level. Thus, they transitioned her to a SNF. Her daughter, who lives locally, visits once each week, and she particularly lights up when her grandchildren spend time with her.

Maria is able to walk and to self-feed. Until recently, she dressed herself, needing only occasional assistance with socks and shoes. Her vision and hearing are grossly intact. She has fallen once since arriving at the SNF but did not sustain significant injury as a result. Maria’s past medical history includes diabetes mellitus, hypertension, osteoarthritis with a previous right total knee arthroplasty, and cataract replacement in both eyes. After her knee replacement 10 yr ago, she began using a walker for stability and safety when ambulating.

After her initial transition into the SNF community 1 yr ago, Maria was doing well; she participated in activities, accepted assistance with self-care, and would often be found smiling during visits with family. However, over the past few months her cognitive abilities have declined. She has lost interest in most activities, has been sleeping more during the day, is tearful at times, and has been resisting care. During family visits, although initially excited, she quickly fatigues and closes her eyes. The nursing staff asked the physician for a referral to occupational therapy services to evaluate and develop a care plan to address her decline in function.

Occupational Therapy Initial Evaluation and Findings

A sample of assessments an occupational therapist might complete during the initial evaluation is included in Table 4. An occupational therapist completed the initial evaluation to start Maria’s plan of care, including use of the Occupational Therapy Profile Template (AOTA, 2020). Maria’s goals were as follows:

Long-Term Goal 1: In 6 wk, Maria will navigate to the dining area from her room with a rolling walker, with standby assistance, with fewer than three verbal–visual–tactile cues for pathfinding and encouragement provided by competent care partner.

Short-Term Goal 1A: In 2 wk, Maria will complete simulated instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) task (e.g., washing dishes) using her bilateral upper extremities, with contact guard assistance for balance in standing, for 3 min.

Short-Term Goal 1B: In 4 wk, Maria will complete commode transfer with standby assistance provided by a competent care partner.

Long-Term Goal 2: In 6 wk, Maria will complete dressing with minimal assistance and fewer than four verbal–visual–tactile cues provided by a competent care partner.

Short-Term Goal 2A: In 2 wk, Maria will wind a skein of yarn into a ball for 5 min, using her bilateral upper extremities with fewer than five cues provided by a competent care partner to sustain activity.

Short-Term Goal 2B: In 4 wk, Maria will sustain participation in meaningful leisure task for greater than 8 min with fewer than three cues provided by a competent care partner.

Table 4.

Occupational Therapy Initial Evaluation Findings for Maria

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (Alexopoulos et al., 1988) |

|

| Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD; Warden et al., 2003) |

|

| Allen’s Cognitive Level Screen–II (ACL–II; Allen, 1991) |

|

| Routine Task Inventory–Expanded (RTI–E; Heimann et al., 1989) |

|

| Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST; Reisberg, 1988) |

|

| Timed Up & Go (TUG; Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991) |

|

| Observations and informal care partner interviews |

|

Note. ADLs = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living.

Occupational Therapy Interventions

Maria was seen for skilled occupational therapy services 3×/wk for 3 wk, decreasing to 2×/wk for 3 wk, to address decreased participation in ADLs because of her progressive dementia, depressive symptoms, and pain. Sessions were a combination of individual and group based. The sessions described in the sections that follow are example interventions that could be implemented with Maria by an occupational therapy assistant after the evaluation was completed by the occupational therapist. The occupational therapy assistant collaborated with the occupational therapist, who continued to evaluate Maria’s response to the intervention plan.

Intervention 1

Maria participated in a combination of individual and group sessions focused on reminiscence to address her cognitive status and depressive symptoms (Duan et al., 2018; K. H. Lee et al., 2020). Group sessions were held 1×/wk for 30 min and included opportunities for remembering historical events and places from the past, tasting favorite foods, looking at keepsakes, and listening to their favorite music. Individual reminiscence sessions were scheduled 1×/wk for 30 min when her daughter was visiting so they could share enjoyment while participating in this co-occupation with a photo album and other keepsakes brought from home. Maria enjoyed participating in the reminiscence sessions and began to look forward to them each week. Staff observed more focus, active participation, and cooperation in her morning ADL routine as a result (CPT code 97150: therapeutic procedures, group; CPT code 97530: therapeutic activity, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 2

To address Maria’s declining cognition, the occupational therapist established a routine physical activity program with restorative nursing in which Maria participated in the facility’s walking club 5×/wk for 15 min immediately after breakfast each day (Duan et al., 2018; Hui et al., 2021). The walking club provided a safe walking environment and included ambient music to keep the participants active and engaged. Maria tolerated the walking group well, and staff observed less daytime sleepiness (CPT code 97530: therapeutic activity, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 3

To address Maria’s reports of pain, the occupational therapy practitioners worked with her to develop a sensory stimulation program (Pu et al., 2019). The sensory stimulation that Maria found to relieve her distress most included massage, showering, music, physical activity, and passive range- of-motion exercises. Once they determined the interventions that were most effective, the occupational therapy practitioners scheduled an individual intervention session that included her care team and her daughter so they could learn which strategies Maria preferred and how best to implement the sensory strategies at times they observed her discomfort. Written and illustration instructions were provided to the care team and Maria’s family. As a result, the care team had more strategies to use when Maria exhibited or reported pain, and they began using the strategies regularly. As a result, Maria’s tearfulness decreased in frequency, and her functional mobility improved (CPT code 97530: therapeutic activity, direct, each 15 min).

Intervention 4

To address functional transfers and independence with dressing, the three certified nursing assistants who regularly work with Maria participated in a training session with her present to learn cueing strategies to decrease her distressed behaviors and improve her participation. Content of the training included use of sensory strategies, nonverbal cues, and environmental modifications. As the result of this training, Maria was more willing to participate in functional transfers and morning dressing tasks. The nursing assistants were more confident in using the strategies learned (CPT code 97535: self-care/home management training, direct, each 15 min).

Outcomes

After the intervention was complete, Maria was more willing to participate in ADLs and was able to complete them with contact guard assist and intermittent visual–verbal–tactile cues for initiation and sequencing. Maria met all goals with the exception of the long-term goal of ambulating to the dining area with standby-assist. Maria’s balance continues to be inconsistent, requiring contact guard assist to decrease her risk of falling. Maria spent longer periods of time alert during the day and, beyond afternoon naps, was rarely asleep during the day. This also appeared to decrease the number of times Maria woke up at night. Maria had fewer tearful episodes, and her affect appeared calmer and more relaxed. As a part of her maintenance program, Maria continued to participate in the reminiscence group and walking group to help maintain her gains. Her daughter reported that visits were more pleasant when they used the photo albums and the strategies discussed in therapy and had begun visiting more frequently. Maria was discharged to restorative nursing to continue to implement the maintenance program to slow further declines in function. The occupational therapist plans to participate in patient care rounds on Maria every 6 mo to identify functional declines requiring additional occupational therapy services. Table 5 lists more details about Maria’s discharge results.

Table 5.

Occupational Therapy Discharge Results for Maria

| Assessment | Discharge Results |

|---|---|

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia | Maria received a score of 6/38, indicating no major depressive episodes. |

| Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale | Maria received a score of 3/10, indicating a decrease in pain. |

| Timed Up & Go | Maria completed the assessment in 12 s, indicating that she is a fall risk. |

| Berg Balance Scale | Maria scored a 30/58, indicating that she remains a moderate fall risk; however, she has made some gains. |

Note. Cognitive assessments were not repeated because these interventions were not designed to improve cognitive level.

Strengths and Limitations of the Current Body of Evidence

There are strengths and limitations related to the current body of evidence in the systematic review that informed these Practice Guidelines. Systematic reviews address specific clinical questions that are guided by an a priori protocol for the question development and review process. No systematic review can address all aspects of a topic; authors make many decisions before conducting the review. No review is perfect, and even the most careful searches sometimes miss articles. The way to reduce these potential sources of bias is to conduct the review using best-practice methodology.

Strengths

The review authors followed best-practice methodology to the best of their ability at every step of the process. The clinical recommendations in these guidelines come from recent, existing high-quality systematic reviews. The guideline team included practitioners, researchers, consumers, and subject matter experts. This methodology is a strength because it allowed for extensive time to conduct the assessment and synthesis of systematic reviews rather than conducting reviews that already exist. In addition, in these Practice Guidelines we include an expert opinion clinical recommendation for an important topic that did not emerge in our evidence-based clinical recommendations.

Limitations: Gaps in the Evidence

Gaps in knowledge exist when there is insufficient, imprecise, inconsistent, or biased information in the literature about an intervention (Robinson et al., 2011). Gaps also exist when the literature is not sufficient to answer a clinical question or the methodology used to synthesize research evidence does not capture certain topics.

A lack of research supporting specific interventions does not mean practitioners should not use those interventions. When working with clients, practitioners considering specific interventions without enough evidence to qualify as evidence-based practice should use expert knowledge and their own training and experience to guide practice. In this section, we pinpoint important gaps in the evidence for interventions and approaches practitioners may consider appropriate for use.

Occupational therapy practitioners need to think about the elements of evidence-based practice as they evaluate these guidelines in light of gaps in the literature related to their clinical practice. Practitioners should consider the following questions when they identify these gaps (Gutenbrunner & Nugraha, 2020):

- What evidence exists?

- What are the best practices associated with providing services to this client population?

- What interventions are contraindicated for this population?

- What outcomes am I hoping to achieve with this client?

- Does evidence exist in another field or discipline related to interventions and desired outcomes that are within the scope of occupational therapy practice?

- What are my client’s preferences and values?

- Does my client prefer one intervention over another?

- Are available resources, cost, or time influencing my client’s preference?

- How might the intervention I am considering affect my client’s performance patterns and roles?

- Does my client find the intervention I am considering meaningful?

- What experience and expertise do I have that can help guide my decisions?

- What types of interventions have I used previously that were effective with similar clients or populations?

- What types of interventions have I used previously that were ineffective with similar clients or populations?

- What potential risks does the intervention I am considering pose to my client or this client population?

- Will the health care system or organization be supportive of this intervention?

- How will I document this intervention?

- How will I document the outcomes associated with this intervention?

- Is it likely that this intervention will be reimbursed?

In the following sections, we present additional information and common occupational therapy interventions for adults living with AD and related NCDs that are not addressed in these guidelines because of a lack of relevant evidence.

Alternative and Expanded Service Delivery Models

Much of the evidence supporting occupational therapy intervention for adults living with AD and related NCDs is focused on direct service provision, specifically individual or group intervention sessions in face-to-face settings. However, there is a lack of evidence that supports alternative service delivery or regulatory models. For example, telehealth has recently received increased attention as a feasible way to enhance access to health care services (Feldhacker et al., 2022); however, telehealth models of care for adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners are limited in the current literature. Similarly, although research suggests that occupational therapy interventions may slow or delay the progression of AD and related NCDs, more evidence is needed (Ham et al., 2021). There are many occupation-based interventions within the scope of occupational therapy that promote health. Developing health service delivery models that include occupational therapy within primary and preventative care may not only maintain functional capacity but also lead to cost savings over time (Clark et al., 2012; Hand et al., 2022). In addition, many adults living with AD and related NCDs benefit from palliative care as the disease progresses. This can include pain management, education, emotional support, or care partner support. Occupational therapy has the potential to play an important role in palliative care; however, the outcomes associated with this have not been extensively studied (Eva & Morgan, 2018). The need for palliative care services for this population will continue to grow; occupational therapy practitioners should work to create a clearly defined practice to address the needs of adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners in this setting. Finally, occupational therapy professionals must consider social determinants (drivers) of health. Information regarding social determinants (drivers) must go beyond documentation. Occupational therapy service delivery may be enhanced with the explicit identification of both core and culturally relevant components of intervention to increase adherence and improve health outcomes (James et al., 2021). In summary, alternative service delivery models will increase access to occupational therapy services for all populations, including those who are marginalized.

Occupation-Based Evaluation and Intervention

Occupational performance is the hallmark of occupational therapy practice. It is important to address all domains of occupational therapy practice (AOTA, 2020); however, engagement in meaningful occupation is the end goal. Therefore, it is important to engage adults living with AD and related NCDs in the authentic occupation during intervention as the ability to generalize progressively declines. Additional research is needed to substantiate the long-held belief that development of habits and routines can improve occupational performance. Much of the existing literature for adults living with AD and related NCDs focuses on evaluations and interventions that address client factors, performance skills, and context rather than occupation and does not consistently measure outcomes at the level of occupation. Eating and feeding are the occupations most often addressed in the literature (Fetherstonhaugh, et al., 2019; Herke et al., 2018; K. H. Lee et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2010; Lui & Kim, 2021); however, none met inclusion criteria for this review, which was limited to systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. Other occupations were far scarcer, or absent, in the research literature, both as interventions and outcomes, limiting clinicians’ ability to reliably use the information in practice (Cibeira et al., 2020; Ham et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2022). Occupation should be a priority at all phases of the occupational therapy process to enhance participation and meaningful engagement. To be specific, more use of occupation is needed to clearly demonstrate the distinct value of occupation as both a process and product. To achieve this outcome, evaluation tools and intervention strategies used in research must include occupation and must be accessible and useful to clinicians.

Dyadic Approaches: Adults Living With AD and Related NCDs and Their Care Partners

Although evidence exists to support occupational therapy interventions to address care partners of adults living with AD and related NCDs (Wang et al., 2021), especially in relation to depression outcomes (Liu et al., 2021), numerous gaps in the literature exist (Butler et al., 2020). Occupational therapy interventions have traditionally focused on individual client outcomes, but a dyadic approach (i.e., one that includes both the client and the care partner) may be another option (Van’t Leven et al., 2018). There is, however, a critical lack of evidence to support a dyadic approach to interventions. Progression of traditional maintenance programs (e.g., routine physical exercise or a routine sensory protocol) toward a more dyadic approach is needed to support the complex needs of adults living with AD and related NCDs and their care partners. Such programs can maximize functional capacity and occupational engagement. Although these programs may be beneficial, additional evidence is needed to indicate the role of occupational therapy in care partner training, measurement of care partner capacity, and relationships between care partner capacity and care recipients’ functional performance. Additional high-level evidence to support care partner and dyadic occupational therapy interventions, such as training to improve knowledge to best facilitate occupational performance outcomes, is needed. Evidence indicates that psychosocial interventions focused on the needs of the dyad—specifically, functional domains, including ADL/IADL dependence and care partner proficiency—improve outcomes for both (Van’t Leven et al., 2013). Therefore, care partners’ needs and capacity, as well as available resources, are important components for occupational therapy practitioners to consider when designing goals and interventions (Rouch et al., 2021).

Person-Centered Assessment and Intervention for Adults Living With AD and Related NCDs

Aging increases differences among people in terms of unique occupational preferences, life choices, and agency (Light et al., 1996). Dementia also presents with unique trajectories of functional abilities, creating a diversity of performance patterns and engagement (Duara & Barker, 2022). In addition, living environments among older adults are highly heterogeneous. These factors warrant the need for person-centered assessment and care tailored to the complexity of each unique adult. Assessments of the environment, autonomy, individual agency, available resources, and care options promote care plans that contribute to optimal occupational engagement. For example, assessment and integration of sensory functioning and processing abilities are needed to maximize behavioral regulation and functional performance for adults living with AD and related NCDs (Cusic et al., 2022; Laver et al., 2022). There is a lack of standardized assessments for adults living with AD and related NCDs that address neurological function as it is related to occupational performance. Just as there are developmental assessments for pediatric populations, greater evidence is needed to support holistic evaluations related to aging with neurodegenerative conditions (Rhodus et al., 2022). When working with this population, occupational therapy practitioners should consider key mechanisms related to performance patterns and capacity, especially related to neurological function and the environment to ensure best practice.

Summary