Abstract

Bleeding tongue-biting episodes during sleep are a rare and alarming situation that can negatively impact the child’s and parents’ sleep, affecting their quality of life. Although highly suggestive of epilepsy, a differential diagnosis should be made with sleep-related movement disorders such as bruxism, hypnic myoclonus, facio-mandibular myoclonus, and geniospasm when this hypothesis is excluded. The clinical history, electroencephalogram, and video-polysomnography are essential for diagnostic assessment. Treatment with clonazepam can be necessary in the presence of frequent tongue biting that causes severe injuries and sleep disturbance. This study reports the challenging case of managing and diagnosing a 2-year-old boy with recurrent tongue biting during sleep since he was 12 months old, causing bleeding lacerations, frequent awakenings, and significant sleep impairment with daytime consequences for him and his family.

Citation:

Cascais I, Ashworth J, Ribeiro L, Freitas J, Rios M. A rare case of tongue biting during sleep in childhood. J Clin Sleep Med. 2024;20(4):653–656.

Keywords: facio-mandibular myoclonus, geniospasm, pediatric, sleep, tongue biting

INTRODUCTION

Tongue biting during sleep, especially if lateralized, has a high prediagnostic probability of being a consequence of an epileptic seizure. However, several other conditions, such as sleep-related movement disorders, including sleep bruxism, hypnic myoclonus, facio-mandibular myoclonus, and geniospasm, can cause this finding.1

Sleep bruxism is an involuntary masticatory muscle contraction resulting in teeth grinding or clenching during sleep.2 It has a typical electroencephalogram (EEG) checkerboard pattern of muscle artifact and a motor pattern with phasic (duration 0.25–5 seconds), tonic (> 2 seconds), or mixed electromyography (EMG) activity.1

Hypnic myoclonus is a sleep-wake transition-stage phenomenon that occurs mainly at sleep onset with associated K-complexes or EEG arousal.1,3 It has been rarely reported in infancy as a cause of tongue biting during sleep and is considered an age-dependent phenomenon related to brain maturation and the development of oral functions.4

Facio-mandibular myoclonus, a rare and underdiagnosed condition that can present as a familial or sporadic form, is characterized by a sudden forceful contraction of the masseter, orbicularis oculi, and oris muscles that can lead to tongue biting during sleep. Although it can present at any age, it is most described in middle-aged males, with a mean onset age of 49 years.5 It is considered a result of activation of the brainstem neuronal network involving the V and VII cranial nerve nuclei. The EMG shows either an isolated or cluster myoclonus in the jaw muscle (< 0.25 seconds).1

Geniospasm is a rare movement disorder, either an autosomal dominant inherited condition or sporadic, characterized by paroxysmal, rhythmic vertical movements of the chin and/or lower lip with accompanying involuntary mentalis muscle contractions that can be associated with nocturnal tongue biting.3 Chin quivering usually manifests in early childhood, can be aggravated by emotional or physical stress, and tends to diminish with age.6 The EMG typically shows bilateral synchronous contraction of the mentalis muscle with a frequency of 2–11 Hz of variable amplitude and a duration of 10–25 milliseconds (or even up to 3 seconds), with a variable interburst pause.7

A differential diagnosis between these conditions is essential for adequate treatment and resolution of the associated sleep problems. Sometimes, it is difficult to determine the exact cause of the tongue biting only by the clinical presentation, which requires specific exams and can be very challenging.

REPORT OF CASE

A 2-year-old boy was referred to a pediatric sleep center due to recurrent tongue biting during sleep since he was 12 months old. He had normal neurodevelopment, and his past medical history was unremarkable. The father had a history of migraines, and the mother had sleepwalking in childhood. There was no personal or family history of movement disorders, recurrent chin quivering, or epilepsy.

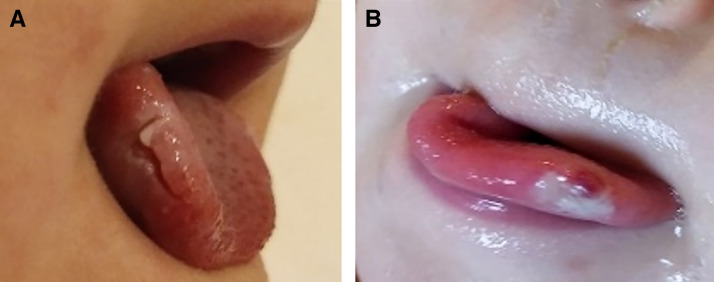

His parents described movements like limb myoclonus followed by tongue biting that caused swelling and bleeding lacerations at the lateral sides of his tongue during sleep, with frequent awakenings and crying episodes, with blood on the sheets. No clear triggers were noted, and he did not snore or present other abnormal movements. Sporadic episodes of leg complaints during the night, daytime agitation, irritability, and bedtime resistance were also noted. His physical examination, including neurological examination, was normal, except for the tongue laceration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Right (A) and left (B) laceration of the tongue and ulceration due to nocturnal tongue biting.

As part of the investigation, the patient had 2 EEGs with sleep recording and no epileptiform activity and a normal dentistry and otolaryngology examination.

Laboratory investigation revealed a ferritin value below 50 ng/mL (24.8 ng/mL) without anemia, hypochromia, or microcytosis, and normal cholecalciferol.

Although tongue lesions improved with time, tongue-biting–related awakenings were frequent despite improved sleep hygiene habits, behavioral strategies, melatonin, tryptophan, and supplementary iron treatment.

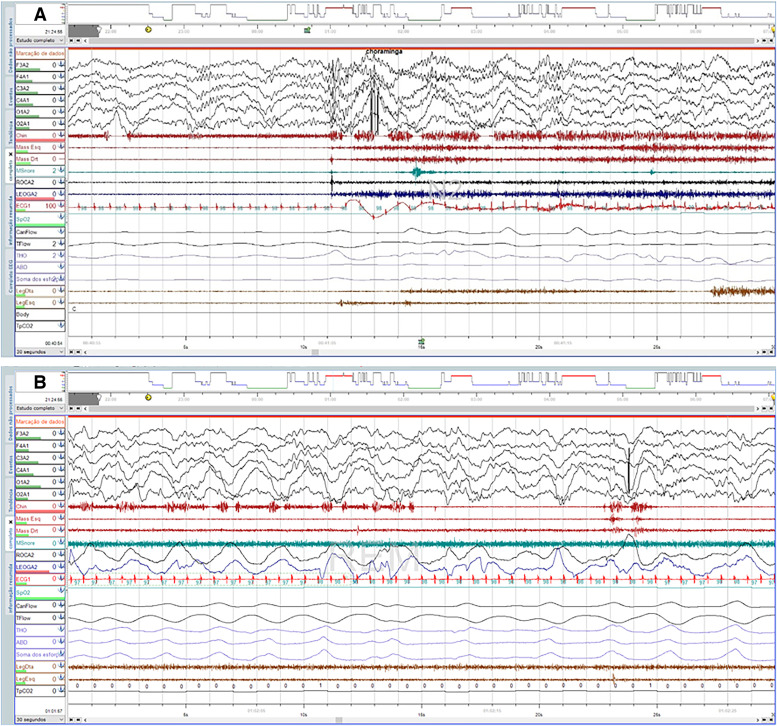

He underwent a level 1 polysomnography (PSG) with supplementary EEG channels, masseters, mentalis, and orbicularis oculi EMG montages. PSG showed a sleep efficiency of 76.3%; 15.9 arousals per hour; a total of 35 awakenings, some with associated crying following several stereotyped events of hypertonia of the mentum; suction movements of the tongue; and clusters of irregularly short bursts of myoclonic EMG activity on masseter and mentalis muscles, closely followed by orbicularis oculi, predominantly during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) stages 2 and 3 sleep (Figure 2A). Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with chin EMG activity was documented (Figure 2B). No periodic leg movements, apnea-hypopnea events, or epileptiform activity were reported. Brain magnetic resonance imaging was also performed and was unremarkable.

Figure 2. Level 1 polysomnography with supplementary electroencephalogram channels, masseters, mentalis, and orbicularis oculi electromyography montages showing a cluster of irregularly brief bursts during NREM stage 2 sleep (A) and REM sleep without atony (B).

NREM = non–rapid eye movement, REM = rapid eye movement.

A low dose of clonazepam was started (0.01 mg/kg) with excellent clinical response. After 2 months of treatment, the patient slept 13 hours a day, frequently without awakenings or tongue-biting episodes, allowing the healing of lesions. Progressive dose reduction (approximately 25% every 2 to 3 weeks) was performed according to the frequency of tongue-biting episodes, which worsened in stressful situations such as infectious intercurrences, with the need to return to the previous dose or maintain dosage. Discontinuation was possible at the end of 15 months of treatment. Presently, at 4 years old, he sleeps 11–12.5 hours per day without awakenings, snoring, or leg complaints. He presents occasional episodes of less severe tongue biting when ill, without laceration or bleeding lesions, and has not had any episodes in the last 7 months.

DISCUSSION

The presence of bleeding tongue-biting episodes during sleep is a rare and alarming situation that negatively impacts the child’s and parents’ sleep, with daytime consequences and poor quality of life, as seen in this case. The investigation should start by excluding epilepsy. The absence of other abnormal movements suggestive of epilepsy and the EEG with sleep recording without documented epileptiform activity suggest the presence of a different diagnosis.

The clinical history, patient age, and the PSG findings of hypertonia of the mentum with suction movements of the tongue and involuntary repetitive contractions of the mentalis muscle bilaterally favor the diagnosis of geniospasm. This conclusion can be made even in the absence of chin quivering during the day, with tongue biting during sleep described as the presenting symptom in some cases.8 Sporadic cases of geniospasm have been described, suggesting that either reduced penetrance or the possibility of having a causative new mutation could explain the lack of family history in this case.3 The literature reports tongue-biting onset age between 10 and 18 months,8 with a median onset at 11 months,7 similar to this case. A systematic review published in 20227 reported a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1 and symptom onset before 1 year of age in 68.1% (particularly in males), with a frequency of 16.2% for nocturnal tongue biting (more likely in males and frequently causing sleep impairment).

In parallel, the EMG recordings of short contractions in the masseter and mentalis closely followed by orbicularis oculi muscles prevailing during NREM sleep are suggestive of sudden forceful myoclonus of masticatory and facial muscles in sleep, ie, facio-mandibular myoclonus.2,9 Despite being more frequent in middle-aged males, either in familial or sporadic form, it can present earlier and coexist with geniospasm. It was suggested that the tongue-biting episodes in cases of geniospasm might be due to an association between these 2 entities,8 which seem to co-occur in this case.

Like facio-mandibular myoclonus,1 geniospasm primarily occurs during NREM sleep, particularly NREM stage 2.6,8 In this patient, there were also movements of the chin in REM sleep (REM sleep without atony). Cases of geniospasm with nocturnal tongue biting have been described with associated REM sleep behavior disorder,7,8 in which REM sleep without atony is typical. However, reports are scarce, and this eventual association needs further clarification. Neuroimaging is not necessary in most patients with sleep-related movement disorders, particularly in those in whom epilepsy has been excluded, who have adequate psychomotor development and a normal neurological examination. In this case, the presence of REM sleep without atony on PSG was the indication for performing brain magnetic resonance imaging, given that rare cases of REM sleep behavior disorder were described as secondary to pathologic processes in the diencephalon or rostral pons.

Either facio-mandibular myoclonus or geniospasm, like other sleep-related movement disorders, exhibits a positive clinical response to benzodiazepines like clonazepam.1,3,10 In the presence of several tongue-biting episodes with tongue lesions and significant sleep disturbance, clonazepam, in recommended dosages for children between 0.01 and 0.1 mg/kg at bedtime, with gradual titration, significantly reduces the episodes and resolves the insomnia,8 as seen in this patient. Mouth guards are a viable nonpharmacologic option to alleviate tongue-biting lesions. However, their use in the pediatric age group is limited by the child’s rapid orofacial growth and difficult cooperation for the impression procedure and daily use.

In this case, PSG with supplementary EEG and EMG was the key to diagnosing these sleep-related movement disorders, and treatment with clonazepam was essential to improving the sleep and quality of life of this child and his family.

Due to the rarity of nonepileptic tongue-biting episodes during sleep, larger-scale studies are needed to provide comprehensive data on the prevalence of this condition, its pathophysiology, and associated disorders, to assess their long-term impact on quality of life and effective treatment options.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the Centro Materno-Infantil do Norte, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Santo António (CMIN-CHUdSA), Porto, Portugal. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patient and his family for agreeing to the submission for publication of his clinical case.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- EMG

electromyography

- NREM

non–rapid eye movement

- PSG

polysomnography

- REM

rapid eye movement

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhang S , Aung T , Lv Z , et al . Epilepsy imitator: tongue biting caused by sleep-related facio-mandibular myoclonus . Seizure. 2020. ; 81 : 186 – 191 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loi D , Provini F , Vetrugno R , D’Angelo R , Zaniboni A , Montagna P . Sleep-related faciomandibular myoclonus: a sleep-related movement disorder different from bruxism . Mov Disord. 2007. ; 22 ( 12 ): 1819 – 1822 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahmoudi M , Kothare SV . Tongue biting: a case of sporadic geniospasm during sleep . J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. ; 10 ( 12 ): 1339 – 1340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kimura Y , Muranaka H , Kojima T , Osari S , Fujita H , Goto A , Yasuda S . Recurrent tongue biting due to hypnic myoclonia in infancy . No To Hattatsu. 2000. ; 32 ( 4 ): 358 – 362 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang X , Yuan N , Wang B , Liu Y . Characteristics of nocturnal facio-mandibular myoclonus in four middle-aged patients . Sleep Med. 2020. ; 68 : 24 – 26 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kharraz B , Reilich P , Noachtar S , Danek A . An episode of geniospasm in sleep: toward new insights into pathophysiology? Mov Disord. 2008. ; 23 ( 2 ): 274 – 276 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teng LY , Abd Hadi D , Anandakrishnan P , Murugesu S , Khoo TB , Mohamed AR . Geniospasm: a systematic review on natural history, prognosis, and treatment . Brain Dev. 2022. ; 44 ( 8 ): 499 – 511 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hull M , Parnes M . Effective treatment of geniospasm: case series and review of the literature . Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2020. ; 10 ( 1 ): 31 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vetrugno R , Provini F , Plazzi G , et al . Familial nocturnal facio-mandibular myoclonus mimicking sleep bruxism . Neurology. 2002. ; 58 ( 4 ): 644 – 647 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goraya JS , Virdi V , Parmar V . Recurrent nocturnal tongue biting in a child with hereditary chin trembling . J Child Neurol. 2006. ; 21 ( 11 ): 985 – 987 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]