Abstract

Maturation of infectious human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) particles requires proteolytic cleavage of the structural polyproteins by the viral proteinase (PR), which is itself encoded as part of the Gag-Pol polyprotein. Expression of truncated PR-containing sequences in heterologous systems has mostly led to the autocatalytic release of an 11-kDa species of PR which is capable of processing all known cleavage sites on the viral precursor proteins. Relatively little is known about cleavages within the nascent virus particle, on the other hand, and controversial results concerning the active PR species inside the virion and the relative activities of extended PR species have been reported. Here, we report that HIV type 1 (HIV-1) particles of four different strains obtained from different cell lines contain an 11-kDa PR, with no extended PR proteins detectable. Furthermore, mutation of the N-terminal PR cleavage site leading to production of an N-terminally extended 17-kDa PR species caused a severe defect in Gag polyprotein processing and a complete loss of viral infectivity. We conclude that N-terminal release of PR from the HIV-1 polyprotein is essential for viral replication and suggest that extended versions of PR may have a transient function in the proteolytic cascade.

Many mammalian and fungal aspartic proteinases (PR) are synthesized as inactive zymogens. Conversion to the mature enzyme occurs autocatalytically and involves removal of a prosegment consisting of 40 to 50 residues from the N terminus of each of these molecules (6). The proteolysis of retroviral Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins is mediated by the viral PR, which also belongs to the aspartic PR and which is encoded as a domain of the Gag-Pol polyprotein in most cases (28). It is presumed that PR is released from the polyprotein by autocatalytic cleavage once virion components are confined in the budding particle. The molecular mechanisms leading to PR activation and autocatalytic release are currently unknown. For human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the 56 residues encoded by the pol open reading frame upstream of the PR region have not been ascribed a specific function and are in a position corresponding to that of the prosegment observed in other aspartic PR. Based on this analogy, it has been suggested that the PR upstream region (termed p6* or p6pol) may serve to regulate HIV PR activity in a manner analogous to that of zymogen conversion and that autocatalytic release of PR from p6* may be a triggering event in HIV polyprotein processing (15, 18). Support for this hypothesis has been drawn from the observation that removal of the p6* region led to enhanced Gag polyprotein processing in an in vitro translation system, suggesting negative regulation of PR activation by p6* (18). However, N-terminally extended versions of PR, mostly generated by introducing point mutations into the N-terminal PR cleavage site or into PR itself, have been shown to be enzymatically active following bacterial expression or in vitro translation (5, 10, 15, 20, 30). These extended PR species appeared to have activities and specificities similar to those of wild-type PR when measurements were made on peptide substrates (5, 30).

Besides cleaving peptide substrates, miniprecursors containing PR cleavage site mutants have also been shown to cleave additional sites within the p6* region leading to p6*-PR fusion proteins (2, 20, 30). Very recently, Almog et al. (2) reported that the predominant PR species in mature HIV type 1 (HIV-1) particles is a 17-kDa protein containing the p6* and PR domains, which suggested that the 99-amino-acid PR observed in heterologous expression systems may not be the PR species active in viral replication. This observation is in contrast to previous reports which showed that N-terminal extensions of HIV PR caused a decrease in autocatalytic release of PR (15) and reduced activity towards polyprotein substrates in trans (30). Furthermore, mutation of the N-terminal PR cleavage site in an HIV expression vector led to considerable reduction in Gag polyprotein processing (30). These results suggested that N-terminal release of PR is required for virion maturation and that the p6*-PR fusion protein observed by Almog et al. (2) should not be sufficient to achieve complete proteolysis. In the present study, we have characterized the PR species in particle preparations from different HIV-1 strains and have constructed a mutation in the N-terminal PR cleavage site in an HIV-1 proviral clone. We report that mature HIV-1 particles contain a predominant 11-kDa PR species which comigrates with bacterially expressed PR and that N-terminal cleavage of PR is required for efficient Gag polyprotein processing and for viral infectivity.

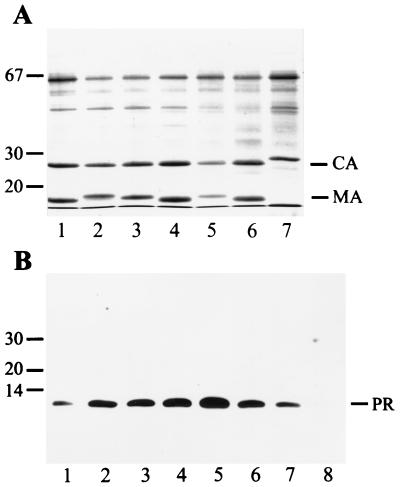

For analysis of particle-associated PR species, we obtained HIV-1 strains NL4-3 (1), SF2 (14), and HXB2 (23) and the IIIB isolate (22), as well as HIV-2 strain CBL20 (27), through the AIDS reagent repository. All HIV strains were passaged in C8166 cells (24). Virus infection was monitored by observing syncytium formation and by indirect immunofluorescence, with serum from an HIV-positive individual for detection. Completely infected C8166 cells were cocultivated at a ratio of 1:10 to 1:20 with fresh MT4 (7) or C8166 cells for 3 days. Subsequently, culture medium was harvested and cleared of cellular debris by a 10-min centrifugation at 400 × g followed by filtration through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. Extracellular particles were collected by centrifugation through a 2-ml cushion of 20% (wt/vol) sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 130,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C, and the pellets were resuspended in PBS. HIV antigens were analyzed by a quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (9), and equal amounts of HIV-specific proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 1A). Major bands corresponding to the viral capsid (CA; the nomenclature of retroviral proteins is in accordance with reference 13) and matrix (MA) proteins were observed in all cases (Fig. 1A) and were also detected with specific antisera against either CA or MA (data not shown). Size variability of structural proteins was observed for the MA proteins from different strains and for the CA protein from HIV-2 isolate CBL20 (Fig. 1A, lane 7).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of particle-associated Gag and PR proteins from several HIV-1 and HIV-2 strains. (A) Particles collected by sedimentation through a cushion of sucrose were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and proteins were detected by Coomassie blue staining. Lanes 1 to 4 show particles from MT4 cells, and lanes 5 to 7 show particles from C8166 cells. HIV-1 strains NL4-3 (lane 1), IIIB (lane 2), HXB2 (lanes 3 and 5), and SF2 (lanes 4 and 6) and HIV-2 strain CBL20 (lane 7) were analyzed in parallel. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left, and the positions of HIV CA and MA proteins are marked on the right. The 65-kDa protein is bovine serum albumin. (B) Immunoblot detection of particle-associated PR species. Proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell) by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked with 10% low-fat dry milk and reacted with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against HIV-1 PR diluted 1:2,000 in buffer containing 5% low-fat dry milk and 0.01% Tween 20. Incubation was performed overnight at room temperature with shaking. Peroxidase-conjugated antirabbit antiserum (Jackson Immunochemicals Inc.) was used as the secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:10,000 and was incubated for 90 min at room temperature. Immune complexes were visualized with the ECL system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In lane 1, 50 ng of purified PR was loaded; lanes 2 to 8 contain particle extracts from HIV-1 strains NL4-3 (lane 2), IIIB (lane 3), HXB2 (lanes 4 and 6), and SF2 (lanes 5 and 7) and HIV-2 strain CBL20 (lane 8), as described above. Note that 10 ng of purified PR was analyzed in the same experiment and was detected on a longer exposure.

For the characterization of particle-associated PR, virus proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum prepared against bacterially expressed purified HIV-1 PR (8) and were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham). Figure 1B shows that all four HIV-1 strains contained the 11-kDa PR species which comigrated with purified PR obtained by recombinant expression in Escherichia coli (Fig. 1B, compare lane 1 with lanes 2 to 7). No difference between particles obtained from C8166 cells (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 7) and those obtained from MT4 cells (lanes 2 to 5) was observed, and no PR-reactive protein in the range of 17 kDa was visible under these conditions. In additional experiments, we deliberately overloaded the gel with highly concentrated HIV-1 particle preparations but did not detect a 17-kDa PR species, even when exposure times of the blot were raised from 10 s (sufficient to obtain the signal shown in Fig. 1B) to 5 min (data not shown). An immunoblot analysis of HIV-1 particles separated on two-dimensional gels also revealed a single PR species with a molecular mass of 11 kDa and an apparent pI of 9.3 (data not shown). Additional proteins of 17 and 24 kDa, which were shown to correspond to MA and CA, were observed if blocking and washing were performed under less-stringent conditions (data not shown). This was likely due to cross-reactivity caused by the relatively large amounts of viral proteins loaded to allow PR detection (Fig. 1B; lane 1 corresponds to 50 ng of PR) with the Gag proteins present at a 20-fold-higher level (i.e., >1 μg in Fig. 1B, lanes 2 to 7). No immunoreactive protein was detected in HIV-2 particles (Fig. 1B, lane 8) because our antiserum poorly cross-reacts with HIV-2 PR.

To analyze whether release of PR from the N-terminally adjacent p6* peptide is required for polyprotein cleavage and viral infectivity, we constructed a point mutation in the N-terminal PR cleavage site in the context of the complete HIV-1 proviral clone pNL4-3 (1). Previous investigations had indicated that HIV PR does not cleave peptides or protein substrates that have a substitution of a β-branched amino acid (Val or Ile) in the P1 position (nomenclature is in accordance with reference 26) of a naturally occurring cleavage site (19, 21). We therefore changed the Phe codon, which corresponds to the P1 position of the N-terminal PR cleavage site, to an Ile codon (TTC to ATC; position 2250 to 2252 of the pNL4-3 sequence) by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (12). The mutated sequence was verified by sequence analysis, and the resulting proviral clone was designated pNL43-PR1. In addition, we recloned a fragment containing the p6*- and PR-coding regions of the PR1 mutant into bacterial expression plasmid pHIV-proPII (11). To analyze whether the mutant sequence is resistant to PR-mediated cleavage, we also synthesized an octapeptide containing the mutated cleavage site (Ser Phe Ser Ile Pro Gln Ile Thr). The altered amino acid is underlined. No cleavage was detectable by high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis upon incubation for 24 h at 37°C at a substrate concentration of 1 mM and an enzyme concentration of 100 nM purified HIV-1 PR, while a control peptide containing the wild-type sequence was readily and completely hydrolyzed under these conditions.

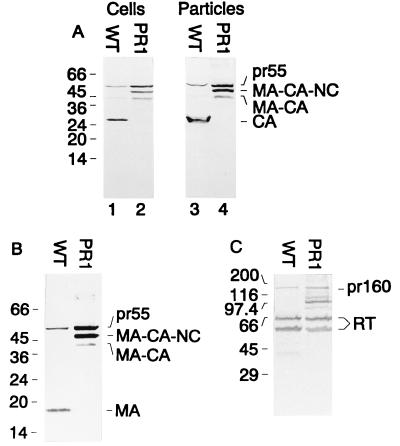

For analysis of cell- and particle-associated antigens, COS-7 cells maintained in Dulbecco modified minimal Eagle’s medium supplemented as described above were transfected with 15 μg of DNA (pNL4-3 or pNL43-PR1) by the modified calcium phosphate method (4). For evaluation of transfection efficiency, 5 μg of an expression vector containing the lacZ gene under the control of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter/enhancer element was cotransfected. Cells and media were harvested 72 h after transfection, and extracellular particles were collected as described above. Figure 2A shows immunoblots of cell and particle extracts reacted with a polyclonal antiserum against CA. Almost complete cleavage of the Gag polyprotein to mature CA was observed in wild-type particles, with little precursor remaining (lane 3). In contrast, PR1-derived particles contained mostly uncleaved pr55gag and two intermediate processing products, with no cleaved CA protein detectable (lane 4). Similar results were obtained when particle extracts were reacted with a polyclonal antiserum against MA (Fig. 2B), which also indicated that the intermediate processing products observed in PR1-derived particles correspond to MA-CA-NC and MA-CA. Thus, the PR1 mutation caused a severe reduction in Gag polyprotein processing, with no mature Gag proteins detectable in extracellular particles. We also analyzed the processing of Pol proteins in extracellular particles with a polyclonal antiserum against reverse transcriptase (RT; Fig. 2C). Again, wild-type particles contained almost exclusively processed heterodimers of RT (p66 and p51), with little Gag-Pol polyprotein remaining. Interestingly, PR1-derived particles also contained a considerable amount of completely processed RT products (estimated at approximately 50% of the wild-type level), with intermediate processing products and some pr160gag-pol remaining. Clearly, the PR1 mutation affected the cleavage of the Gag polyprotein much more than the cleavage of the Pol domain of the Gag-Pol polyprotein, and only a moderate reduction of mature Pol-derived products was observed. The PR-RT, RT-RNase H, and RT-integrase cleavage sites were processed approximately equally in the case of the PR1 mutation since relative amounts of the RT heterodimer in wild-type and PR1-derived particles appeared unaltered (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of gag and pol gene products after transient transfection. COS-7 cells transfected with pNL4-3 (WT) or pNL43-PR1 (PR1) and corresponding media were harvested 72 h after transfection. Lysates of transfected cells (A, lanes 1 and 2) and particles sedimented through a sucrose cushion (A, lanes 3 and 4, B, and C) were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Western blots were stained with rabbit polyclonal antiserum to CA (A; dilution, 1:500) (16), with sheep polyclonal antiserum to MA (B; dilution, 1:200), or with rabbit polyclonal antiserum to RT (C; dilution, 1:200) (16). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antirabbit or antisheep antisera (Jackson Immunochemicals Inc.) were used as the secondary antibody, and immune complexes were visualized by color reaction. Molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left, and relevant HIV-specific proteins are indicated on the right.

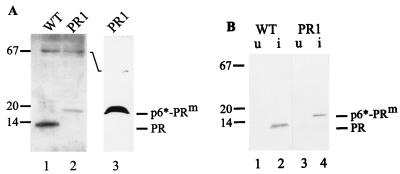

Wild-type and PR1-derived particles were also analyzed for PR-reactive proteins. Figure 3A shows that wild-type HIV-1 particles obtained by transfection of nonpermissive COS-7 cells contained the 11-kDa PR species (Fig. 3A, lane 1), as had been observed for several viral strains obtained by infection. This PR protein comigrated with purified bacterially expressed PR (data not shown), and no PR-reactive product of approximately 17 kDa was observed (Fig. 3A, lane 1). Particles derived from PR1-transfected cells, on the other hand, exclusively contained 17-kDa PR-reactive proteins, with no evidence for mature PR, even on overexposed immunoblots (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 3). The same result was observed for particles obtained from transfected HeLa cells (data not shown). Wild-type and PR1-derived particle preparations, normalized for CA and RT proteins, contained approximately equivalent amounts of PR-reactive proteins, indicating that our antiserum detected the 11- and 17-kDa proteins equally well. Expression of precursor proteins containing the wild-type p6*-PR sequence or the PR1 mutant sequence in E. coli yielded a 17-kDa PR-reactive protein in the case of the mutant (Fig. 3B, lane 4), with no evidence of further processing to the wild-type 11-kDa PR (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Taken together with the results of peptide cleavage (see above), these results show that the Phe-to-Ile substitution in the P1 position of the N-terminal PR cleavage site completely prevents processing at this site. Lack of this cleavage does not prevent processing of other sites, especially in the Pol domain of the Gag-Pol polyprotein. These sites include the sites of the known cleavages separating PR, RT, and integrase and also a site that separates the p6* domain of Pol from the Gag domain of the precursor protein. This site most likely corresponds to the sequence Asp Leu Ala Phe * Leu Gln Gly Lys (the asterisk denotes the scissile bond) in the N-terminal region of p6*, which has been shown previously to be a substrate for PR (2, 20, 30). Cleavage at this site generates an apparently stable extended PR species which is capable of cleaving all other sites in the Pol domain (albeit with reduced efficiency) but which yields only weak cleavage of the viral Gag polyprotein.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of PR species in wild-type (WT) and PR1-derived virus particles following E. coli expression. (A) Particles from WT (lane 1) or PR1-transfected (lanes 2 and 3) COS-7 cells were collected from the culture media and resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Western blots were stained with rabbit polyclonal antiserum to PR and were visualized by ECL. In lane 3, particles collected from three transfections were combined to produce an increased signal and were analyzed on a different gel system, which gives higher resolution in the low-molecular-mass region of the gel (25). (B) E. coli BL21 DE3 cells were transformed with plasmids pHIV-proPII, containing either the WT sequence or the PR1 mutation. Bacteria were grown and induced as described previously (11), and samples of uninduced (u) and induced (i) bacteria were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels as indicated above each lane. The blot was reacted with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against PR, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antirabbit serum and immune complexes were detected by color reaction. P6*-PRm designates the fusion protein containing the Phe-to-Ile cleavage site mutation.

Particles derived from wild-type and PR1-transfected COS-7 cells were analyzed for infectivity on HIV-1-permissive MT4 and C8166 cells. No infection was detected over an observation period of up to 28 days by using undiluted or diluted medium from three independent transfections with the PR1 construct. Coculture of these cells with fresh MT4 cells also failed to yield any infection, and no reversion was observed in the course of this study. In contrast, medium from wild-type-transfected cells contained infectious HIV particles with a titer of approximately 105 to 106 per ml, and infection was always detectable after 2 to 5 days (data not shown). Thus, mutation of the PR N-terminal cleavage site completely abolished virus infectivity. Most likely, no condensation of immature spherical particles occurred in the case of the PR1-derived particles due to the severe reduction in Gag polyprotein processing, and the lack of infectivity may reflect a defect in capsid uncoating, similar to what is seen for PR-deficient mutants.

In this report, we have shown that the predominant species of PR in HIV-1 particles is an 11-kDa protein which corresponds to the 99-amino-acid PR obtained after recombinant expression and autocatalytic release in heterologous systems. This 11-kDa PR was detected in four different HIV-1 strains and in particles obtained from four different cell lines, with no evidence for a significant amount of an extended 17-kDa PR species. In a previous report, Almog et al. (2) had observed a 17-kDa PR in HIV-1 particles (strains IIIb and MN) obtained from monocytic cell line U937 and suggested that p6*-PR may be the active form of PR inside the viral particles. This discrepancy may be due to a significant difference in polyprotein processing in U937 cell-derived HIV-1 particles or to the relative specificity of the antisera employed. It appears unlikely, however, that p6*-PR can achieve sufficient proteolysis for viral maturation since mutation of the N-terminal PR cleavage site (without altering the PR sequence itself) led to a severe reduction in Gag polyprotein processing (reference 20 and this study) and to complete loss of viral infectivity (this study).

Previous studies by several groups indicated that miniprecursors containing p6* and PR are active (5, 15, 20, 30), a finding which is in agreement with our result that mutation of the N-terminal PR cleavage site does not completely block other cleavages of the Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins. However, bacterially expressed or in vitro-translated miniprecursors exhibited no major kinetic difference in peptide cleavage, while a severe reduction in Gag polyprotein processing was observed inside PR1 virions. This difference could be due either to a restricted accessibility of the substrate inside virus particles for extended PR or to reduced processing of protein substrates, as had been suggested from a previous study (20). Much less cleavage of Gag polyproteins than of the Pol domains was observed; this may be explained by the better accessibility of the Pol segment to the extended PR, which is likely to be localized inside the Gag shell and which may not be able to reach the tightly packed outer shell. Since Gag appears to be a rod-like structure with the N-terminal MA domains closely apposed to the lipid bilayer and the C-terminal parts pointing inward (17), one would presume that the Pol domains (which amount to only 5% of the Gag domains) are organized less tightly in the interior part of the particle. It is interesting to note that cleavage of precursor polyproteins derived from immature particles by exogenous PR showed efficient cleavage of Gag and considerably reduced and partly aberrant cleavage of the Pol domains (8), which may also be due to the relative accessibilities of individual sites. Taken together, these two studies suggest a significant difference in endogenous versus exogenous processing of Pol proteins.

Mutation of the N-terminal PR cleavage site in the context of a complete provirus led to formation of a p6*-PR fusion protein which is likely cleaved at the previously described site at the very beginning of the Pol sequence (2, 20, 30). This N-terminally extended PR is proteolytically active and cleaves the Pol domain quite efficiently. Conceivably, p6*-PR may also serve as a transient intermediate in normal HIV proteolysis. The N- and C-terminal sequences of PR are part of a tightly packed four-strand β sheet, which constitutes the dimer interface of the active PR dimer (29). Autocatalytic release of PR requires that one strand be dislodged from the β sheet and folded into the active site of a preformed PR dimer, which at this stage is part of the entire pr160gag-pol molecule. Kinetic evidence for intramolecular cleavage at the N terminus of PR has been presented for bacterially expressed PR proteins containing N- and C-terminal extensions (5, 15), but the efficiency of cleavage was significantly lower if longer N-terminal extensions were present (15). Intramolecular cleavage at the N terminus of PR may therefore be difficult to achieve for the entire Gag-Pol polyprotein. The N-terminally adjacent p6* region has been shown to have no stable structure (3) and may serve as a flexible hinge linking the folded Gag and Pol domains on the polyprotein. Conceivably, this flexible chain, which is not part of the dimer interface, may be folded into the PR substrate binding pocket, and initial cleavage at the N terminus of p6* separates the Gag and Pol domains, leaving a short N-terminal extension on PR. Subsequent intramolecular cleavage at the N terminus of PR leads to C-terminally extended PR species which have been shown to be catalytically competent (15) and eventually give rise to mature PR, which performs the majority of cleavages in the Gag polyprotein. If the initial cleavage event is slow, this may also have a regulatory effect on the downstream events in the proteolytic cascade.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to R. Welker and K. Wiegers for preparing virus stocks, to J. Konvalinka and I. Bláha for peptide cleavage, and to A.-M. Heuser for assistance. We also thank J. Konvalinka for suggestions and for critically reading the manuscript. We are grateful to the NIAID AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for HIV strains and antiserum.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the German ministry for education and research to H.-G.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almog N, Roller R, Arad G, Passi-Even L, Wainberg M A, Kotler M. A p6pol-protease fusion protein is present in mature particles of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:7228–7232. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7228-7232.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beissinger M, Paulus C, Bayer P, Wolf H, Rösch P, Wagner R. Sequence-specific resonance assignments of the 1H-NMR spectra and structural characterization in solution of the HIV-1 transframe protein p6*. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0383k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Co E, Koelsch G, Lin Y, Ido E, Hartsuck J A, Tang J. Proteolytic processing mechanisms of a miniprecursor of the aspartic proteinase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1248–1254. doi: 10.1021/bi00171a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies D R. The structure and function of the aspartic proteinases. Annu Rev Biochem Biophys Chem. 1990;19:189–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harada S, Koyagani Y, Yamamoto N. Infection of HTLV-III/LAV in HTLV-I carrying cells MT-2 and MT-4 and application in a plaque assay. Science. 1985;229:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.2992081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konvalinka J, Heuser A M, Hruskova-Heidingsfeldova O, Vogt V M, Sedlacek J, Strop P, Kräusslich H-G. Proteolytic processing of particle associated retroviral proteins by homologous and heterologous viral proteinases. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konvalinka J, Litterst M A, Welker R, Kottler H, Rippmann F, Heuser A-M, Kräusslich H-G. HIV-1 proteinase (PR) active-site mutation causes reduced PR activity and PR-mediated cytotoxicity without apparent effect on virus maturation and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:7180–7186. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7180-7186.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotler M, Arad G, Hughes S H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag-protease fusion proteins are enzymatically active. J Virol. 1992;66:6781–6783. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6781-6783.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kräusslich H-G, Schneider H, Zybarth G, Carter C A, Wimmer E. Processing of in vitro-synthesized gag precursor proteins of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 by HIV proteinase generated in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1988;62:4393–4397. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4393-4397.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leis J, Baltimore D, Bishop J M, Coffin J, Fleissner E, Goff S P, Oroszlan S, Robinson H, Skalka A M, Temin H M, Vogt V M. Standardized and simplified nomenclature for proteins common for all retroviruses. J Virol. 1988;62:1808–1809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1808-1809.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy J A, Hoffman A D, Kramer S M, Landis J A, Shimabukuro J M, Oshiro L S. Isolation of lymphocytopathic retroviruses from San Francisco patients with AIDS. Science. 1984;225:840–842. doi: 10.1126/science.6206563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis J M, Nashed N T, Parris K D, Kimmel A R, Jerina D M. Kinetics and mechanism of autoprocessing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease from an analog of the Gag-Pol polyprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7970–7974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mergener K, Fäcke M, Welker R, Brinkmann V, Gelderblom H R, Kräusslich H-G. Analysis of HIV particle formation using transient expression of subviral constructs in mammalian cells. Virology. 1992;186:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nermut M V, Hockley D J. Comparative morphology and structural classification of retroviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partin K, Zybarth G, Ehrlich L, DeCrombrugghe M, Wimmer E, Carter C. Deletion of sequences upstream of the proteinase improves the proteolytic processing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4776–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettit S C, Simsic J, Loeb D D, Everitt L, Hutchison III C A, Swanstrom R. Analysis of retroviral protease cleavage sites reveals two types of cleavage sites and the structural requirements of the P1 amino acid. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14539–14547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phylip L H, Mills J S, Parten B F, Dunn B M, Kay J. Intrinsic activity of precursor forms of HIV-1 proteinase. FEBS Lett. 1992;314:449–454. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81524-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poorman R A, Tomasselli A G, Heinrikson R L, Kézdy F J. A cumulative specificity model for proteases from human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, inferred from statistical analysis of extended substrate database. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14554–14561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popovic M, Sarngadharan M G, Read E, Gallo R C. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science. 1984;224:497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.6200935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratner L, Fisher A, Jagodzinski L L, Mitsuya H, Liou R-S, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Complete nucleotide sequence of functional clones of the AIDS virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1987;3:57–69. doi: 10.1089/aid.1987.3.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salahuddin S Z, Markham P D, Wong-Staal F, Franchini G, Kalyanaraman V S, Gallo R C. Restricted expression of human T-cell leukemia-lymphoma virus (HTLV) in transformed human umbilical cord blood lymphocytes. Virology. 1983;129:51–64. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schäger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active sites in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz T F, Whitby D, Hoad J G, Corrah T, Whittle H, Weiss R A. Biological and molecular variability of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 isolates from The Gambia. J Virol. 1990;64:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5177-5182.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogt V M. Proteolytic processing and particle maturation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:95–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wlodawer A, Miller M, Jaskolski M, Sathyanarayna B K, Baldwin E, Weber I T, Selk L, Clawson L, Schneider J, Kent S B H. Conserved folding in retroviral proteases: crystal structure of a synthetic HIV-1 proteinase. Science. 1989;245:616–621. doi: 10.1126/science.2548279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zybarth G, Kräusslich H-G, Partin K, Carter C. Proteolytic activity of novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteinase proteins from a precursor with a blocking mutation at the N terminus of the PR domain. J Virol. 1994;68:240–250. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.240-250.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]