Abstract

Multiple extracellular domains of the CC-chemokine receptor CCR5 are important for its function as a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) coreceptor. We have recently demonstrated by alanine scanning mutagenesis that the negatively charged residues in the CCR5 amino-terminal domain are essential for gp120 binding and coreceptor function. We have now extended our analysis of this domain to include most polar and nonpolar amino acids. Replacement of alanine with all four tyrosine residues and with serine-17 and cysteine-20 decrease or abolish gp120 binding and CCR5 coreceptor activity. Tyrosine-15 is essential for viral entry irrespective of the test isolate. Substitutions at some of the other positions impair the entry of dualtropic HIV-1 isolates more than that of macrophagetropic ones.

Fusion of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope with the plasma membrane is mediated by CD4 (10, 22, 26, 27) and proteins belonging, or related, to the chemokine receptor family (1, 8, 11, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19, 24). CCR5 is a coreceptor for macrophage (M)-tropic strains of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) (1, 8, 11, 14, 16) and plays a major role in viral transmission (25, 28, 32), whereas T-cell-tropic strains that use CXCR4 can appear as HIV-1 infection progresses but are rarely transmitted (9, 34). CXCR4 is also used by most T-cell line-adapted (TCLA) isolates (3, 19). Most primary HIV-1 isolates are dualtropic since they are capable of using both CCR5 and CXCR4, although not necessarily with the same efficiency (9, 14, 34). These viruses are particularly interesting from a molecular perspective since they have evolved to interact with (at least) two coreceptors that have significantly divergent primary sequences. Recent studies show that different extracellular domains of CXCR4 are required by dualtropic and TCLA viruses for entry into CD4+ cells (6, 35). Similarly, it has been demonstrated that multiple extracellular domains of CCR5 are required for coreceptor function and that they are used differently by M-tropic and dualtropic HIV-1 strains (4, 29, 30).

We have recently shown that three negatively charged residues—aspartic acids (D) at positions 2 and 11 and glutamic acid (E) at position 18—in the amino-terminal domain (Nt) of CCR5 play an important role in gp120 binding and in the entry of both M-tropic and dualtropic HIV-1 isolates (17). This suggests that a gp120-binding domain, which is perhaps part of a more extensive binding site that includes residues in the other extracellular loops (ECL), is located in the Nt of CCR5. We therefore performed a more comprehensive alanine scanning mutagenesis study of the Nt to determine the full extent of this functional domain, as well as to specifically test for differences in amino acid usage by M-tropic and dualtropic isolates.

Using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis we individually changed the polar residues serine (S), cysteine (C), tyrosine (Y), threonine (T), asparagine (N), and glutamine (Q) and the nonpolar proline (P) residues to alanines (A), as described previously (17). All CCR5 molecules used in this study had a nine-residue hemagglutinin (HA) tag as a carboxy-terminal extension, to allow detection by dot blotting with anti-HA antibodies (3). We tested the CCR5 mutants for their abilities to mediate the entry of different HIV-1 isolates into U87MG-CD4 cells, a human neuronal cell line that does not express CCR5, CCR3, or CXCR4 and that is therefore not infectable by any of our test isolates (7, 11, 12, 17). Briefly, cells were lipofected with wild-type or mutant CCR5 genes and then infected with 200 to 500 ng of p24 per ml of NL-43/luc/Δenv viruses, complemented in trans by envelope glycoproteins from ADA (20), JR-FL (23), DH123 (33), and Gun-1 (34, 36). To determine if HIV-1 entry mediated by certain CCR5 mutants was still sensitive to inhibition by CC-chemokines, infections were carried out in the presence of 2 μg of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or RANTES per ml. Luciferase activity in cell lysates was measured 48 h postinfection with the Luciferase Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression levels of mutant and wild-type CCR5s were determined in each experiment. Thus, lipofected cells were lysed with detergent (17), and clarified lysates were diluted (1:1) in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 1 mM dithiothreitol. A 70-μl aliquot, corresponding to approximately 105 cells, was loaded onto a Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) by using a Bio-Dot apparatus (Bio-Rad). Detection of CCR5 expression was carried out with rabbit anti-HA-tag antibody diluted 1:103 (Berkeley Antibody Company), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G, also diluted 1:103 (Amersham) (17). HRP activity was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence Western-blotting reagents (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and autoradiographs were scanned with the IS-1000 digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech Corporation). Integrated density values (i.d.v.) were used to standardize luciferase activity. (We obtain very similar CCR5 expression level values by dot blotting and Western blotting [data not shown; 17].) The relationship between wild-type CCR5 expression levels and HIV-1 entry efficiency was determined to be linear over the relevant 10-fold range (data not shown).

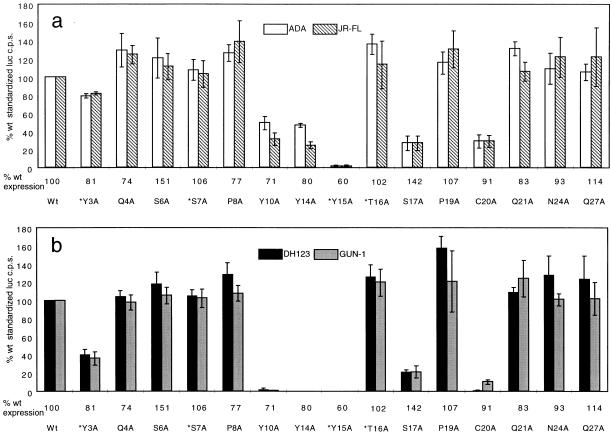

We tested the ability of each mutant to mediate the entry of two M-tropic strains, ADA and JR-FL, and two dualtropic strains, DH123 and Gun-1 (Fig. 1). Substitutions of alanine for tyrosine residues at positions 3, 10, 14, and 15, and for S17 and C20, impaired HIV-1 entry in an isolate-dependent manner for some of the substitutions. The Y3A substitution had very little effect on ADA and JR-FL entry, while decreasing DH123 and Gun-1 entry by ∼60%. Changing Y10 or Y14 to alanine decreased the entry of both M-tropic isolates by ∼50% but reduced the entry of both dualtropic isolates to undetectable levels. In contrast, the Y15A substitution abolished entry of all four isolates of both phenotypes. The C20A mutant was a completely nonfunctional coreceptor for DH123 but functioned weakly for Gun-1 and the M-tropic isolates. Finally, the coreceptor activity of the S17A mutant was decreased by about fivefold for all isolates. We also noted that all of the other substitutions, especially P8A, T16A, and P19A, increased the efficiency of CCR5 usage by 10 to 40%; this could not be attributed solely to the higher expression levels of some of these mutants (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 coreceptor function of CCR5 amino-terminal mutants. U87MG-CD4 cells transiently expressing wild-type or mutant coreceptors were infected with M-tropic isolates NLluc/ADA (white bars) and NLluc/JR-FL (hatched bars) (a) or dualtropic isolates NLluc/DH123 (black bars) and NLluc/Gun-1 (shaded bars) (b). Luciferase activities (luc c.p.s.) were measured 48 h postinfection and standardized for receptor expression levels which are indicated below the x axis as percentages of wild-type (wt) expression. The coreceptor activity of each mutant, expressed as a percentage of wild-type coreceptor activity, is calculated by the expression [(mutant luc c.p.s./wt luc c.p.s.)/(mutant i.d.v./wt i.d.v.)]×100% and is the mean ± the standard deviation of three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. An asterisk indicates that the amino acid is also different in murine CCR5.

To further probe the structural requirements for CCR5 coreceptor activity, we also changed each of the tyrosine residues to a phenylalanine. In this manner we removed the para-hydroxyl groups while retaining the aromatic benzene ring in the side chain. The Y3F, Y10F, and Y14F mutants had impaired coreceptor activities, similar to those observed for the alanine substitutions at these positions (Fig. 2, a and b). However, in marked contrast to the effect of the Y15A substitution, the mutant with the Y15F substitution had wild-type coreceptor activity for the JR-FL M-tropic isolate and 60% of wild-type coreceptor activity for the DH123 dualtropic isolate (Fig. 2, a and b). We conclude that the phenolic side chains of the four tyrosines in the Nt of CCR5 do not interact in identical fashion with other amino acid side chains, be they within gp120 or the other ECL. Since the phenylalanine substitution is poorly tolerated at positions 3, 10, and 14, it is the hydroxyl groups of these tyrosine residues that are important for coreceptor function, perhaps because they form hydrogen bonds with other polar residues. However, the hydroxyl group of Y15 is dispensable but the benzene ring is important since the Y15F mutant is a functional coreceptor but the Y15A mutant is not. This ring could be involved in hydrophobic interactions with other aromatic or nonpolar side chains. Alternatively, Y15 could be involved in cation-π interactions (15) and may, along with the three negatively charged amino acids in the Nt, form a cation-binding site in this region of CCR5. The gp120- and CD4-dependent fusion process has been shown to be Ca2+ dependent (13); perhaps this ion is required to maintain the CCR5 Nt in a particular conformation?

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 coreceptor function of Y→F substitutions in the amino terminus of CCR5. Each tyrosine in the CCR5 Nt was individually changed to a phenylalanine (a) or an alanine (b). Coreceptor activities of these mutants were tested in U87MG-CD4 cells by using NLluc/JR-FL, (hatched bars) and NLluc/DH123 (black bars). The coreceptor activity of each mutant is expressed as a percentage of wild-type (wt) coreceptor activity and is standardized for receptor expression levels, indicated below the x axis, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. luc c.p.s., luciferase activity.

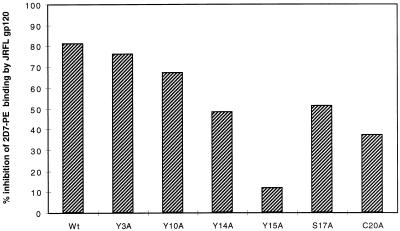

To test if the Y3, Y10, Y14, Y15, S17, and C20 residues interact with gp120, we used a competition assay which measures the ability of JR-FL gp120 (37) to inhibit the binding of 2D7-PE (LeukoSite), a phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-labeled CCR5-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) (5, 38, 39). We have shown previously that this MAb is able to bind efficiently to HeLa cells colipofected with CD4 and the CCR5 Nt mutants and infected with T7 polymerase-expressing vaccinia virus (vTF7) in order to boost receptor and coreceptor expression (17). The binding of 2D7-PE to wild-type CCR5 is strongly inhibited (80%) by the prior addition of JR-FL gp120, indicating that the interaction of gp120 and 2D7-PE with the coreceptor is mutually exclusive (Fig. 3) (17). However, gp120 only partially inhibited the binding of 2D7-PE to the Y3A, Y10A, Y14A, S17A, and C20A mutants and was almost completely ineffective at blocking 2D7-PE binding to the Y15A mutant (Fig. 3). The most likely explanation of this result is that gp120 binds to the wild-type CCR5 molecule in a way that sterically hinders the binding of 2D7-PE to its epitope in ECL2 and that gp120 binds poorly to the Nt mutants. The Nt mutations probably do not affect 2D7-PE binding to CCR5. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of lipofected HeLa cells stained with this MAb detects expression level ratios of wild-type to mutant coreceptors similar to those detected by dot blotting with the anti-HA antibody. CCR5 mutant expression levels varied by approximately ±50% of wild-type expression levels. There was a good correlation between loss of gp120 binding and ability of the CCR5 mutants to support HIV-1 entry (cf. Fig. 1 and 3), as found previously for the D and E mutants (17).

FIG. 3.

Competition between gp120 and CCR5 MAb 2D7-PE for CCR5 binding. HeLa cells cotransfected with CD4 and either wild-type (wt) or mutant CCR5 and infected with vTF7 to enhance receptor expression were preincubated with or without 10 μg of gp120 (JR-FL) per ml before the addition of 200 ng of the PE-labeled 2D7 MAb per ml and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis to determine mean fluorescence intensity (m.f.i.). Results are expressed according to the following equation: percent 2D7-PE binding inhibition = [1 − (m.f.i. in the presence of gp120/m.f.i. in the absence of gp120)] × 100.

In our previous study we demonstrated that only the D11A mutant was a deficient coreceptor and that the residual activity it possessed was insensitive to the inhibitory effects of the CC-chemokine ligands of CCR5: MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES (17). Several other mutants which had wild-type coreceptor activity were also impaired for CC-chemokine inhibition of viral entry (17). Our results implied that the binding sites of gp120 and the chemokines on CCR5 were only partially overlapping. We have now tested whether the new mutants with impaired (but not absent) coreceptor activity were sensitive to CC-chemokine-mediated inhibition. Since the majority of the mutants were strongly impaired as coreceptors only for dualtropic isolates, it was possible to use the M-tropic JR-FL isolate to measure CC-chemokine sensitivity. Only the Y15A mutant could not be tested in this way since it was completely inactive with M- and dualtropic viruses. Of the mutants we tested only the C20A mutant was partially insensitive to MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES (Table 1). The cysteine at position 20 is predicted to form a disulfide bond with C269 in the third ECL (31); it probably constrains the Nt and ECL3 in a conformation that is important for both chemokine binding and gp120 binding. The other substitutions which impaired HIV-1 entry had little or no effect on CC-chemokine-mediated inhibition of entry (Table 1), which further supports the notion that the gp120 and the CC-chemokine binding sites only partially overlap.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of coreceptor function by CC-chemokinesa

| CCR5 mutation | Relative % inhibitionb by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-1α | MIP-1β | RANTES | |

| Y3A | 93 | 67 | 75 |

| Y10A | 126 | 94 | 129 |

| Y14A | 119 | 103 | 137 |

| Y15A | nd | nd | nd |

| S17A | 92 | 94 | 118 |

| C20A | 12 | 40 | 28 |

U87MG-CD4 cells were transiently lipofected with wild-type or mutant CCR5 and then infected with NLluc/JR-FL, in the presence or absence of 2 μg of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, or RANTES per ml. Luciferase activity (luc c.p.s.) was measured 48 h postinfection. The relative percent of inhibition by a CC-chemokine for each mutant is defined as [1 − (luc c.p.s. with chemokine/luc c.p.s. without chemokine)]/[1 − (wild-type luc c.p.s. with chemokine/wild-type luc c.p.s. without chemokine)] × 100%. Each value of relative percent of inhibition by a CC-chemokine is a mean of three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. The mutation of the mutant coreceptors for which the relative percent of inhibition is <50% of that observed with wild-type CCR5 and the associated percentages are in boldface. nd, not done.

The percent inhibition for the wild-type coreceptor by each CC-chemokine was defined as 100%.

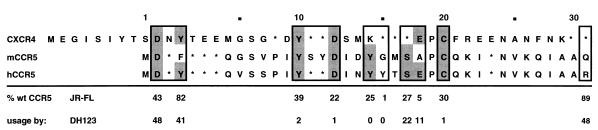

Our results clearly demonstrate that the four tyrosine residues, one serine residue, and one cysteine residue in the CCR5 Nt are important for CCR5 coreceptor function. We propose that all of these residues form a section of a composite gp120 binding domain in the amino-terminal region of CCR5. Negatively charged amino acids D2 and E18 and polar residues Y15 and S17 are equally important for entry of all the viral isolates that we have tested (17). In contrast, residues Y3, Y10, D11, Y14, C20, and R31 are more important for CCR5 coreceptor usage by dualtropic isolates than by M-tropic ones (Fig. 4). Only C20 is also important for CC-chemokine-mediated inhibition of JR-FL entry; it may affect coreceptor conformation rather than be involved in a direct interaction with gp120. In light of these findings it is surprising that the Nt of murine CCR5 is capable of functioning in the context of human CCR5 (2, 4, 29) since it lacks both E18 and Y15 and since Y10 and D11 are separated by two extra amino acids (Fig. 4). Additional mutagenesis studies may clarify this observation.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of amino-terminal sequences of CCR5, murine CCR5, and CXCR4. The numbers below relevant residues of the human CCR5 (hCCR5) sequence indicate the percentages of wild-type (wt) coreceptor activity of the corresponding alanine mutants for JR-FL (M-tropic) and DH123 (dualtropic) viral isolates. Possible functional motifs are outlined, and sequence homologies between human CCR5, murine CCR5 (mCCR5), and human CXCR4, within these motifs, are shaded.

It was not unexpected that M-tropic and dualtropic isolates use the CCR5 amino terminus differently. Previous studies have shown that chimeras made between human and murine CCR5 molecules are not used equally well as coreceptors by different HIV-1 strains; the dualtropic 89.6 virus can only use human CCR5 carrying the Nt (MHHH) or ECL1 (HMHH) of murine CCR5 (4), while a number of other dualtropic strains are capable of using only HMHH (29). Indeed, both of these studies also demonstrate that, even among the M-tropic viruses, there are differences in the ways they interact with CCR5 chimeras (4, 29). Similarly, dualtropic HIV-2 strain ROD requires both the Nt and ECL2 of CXCR4, while TCLA virus LAI requires only ECL2, although additional differences between HIV-1 and HIV-2 may account for these results (6).

It will be interesting to determine if the contributions from the HIV-1 binding sites in the CCR5 and CXCR4 Nts are similar and if the contributions from the other extracellular domains are also similar. A sequence comparison of these two coreceptors shows that there are significant homologies in critical regions of their Nts (Fig. 4), which can also be found in the Nts of the more recently identified coreceptors such as BOB/gpr15, Bonzo/STRL33/TYMSTR, and gpr1 (12, 18, 24). Structural similarities between CCR5 and CXCR4 could explain why the virus has evolved to use these two receptors. Alternatively, gp120 of dualtropic isolates may interact with different motifs on the two coreceptors. In that case, CCR5 and CXCR4 expression patterns and/or their ability to associate with CD4 may have forced HIV-1 to evolve two more or less separate binding sites to accommodate the usage of both coreceptors. This may not be the more likely possibility given the ease with which phenotypic switches occur, sometimes as a consequence of a single residue change in gp120 (21). Our data are consistent with the existence of a single coreceptor binding site on gp120 for dualtropic isolates. This site may be sufficiently broad and flexible to accommodate similar, but not identical, motifs in both the CCR5 and the CXCR4 Nts. In contrast, gp120s from M-tropic isolates, which bind only to CCR5, may have a much more restricted coreceptor binding site. This perhaps explains why M-tropic isolates depend on far fewer residues in the Nt of CCR5 than do dualtropic strains.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by RO1 AI41420 and by Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. T.D. holds a Diamond Fellowship; J.P.M. is an Elizabeth Glaser Scientist of the Pediatric AIDS Foundation.

We thank Hiroo Hoshino for kindly providing the Gun-1 isolate, Riri Shibata for the DH123 isolate, William Olson for JR-FL gp120, and Lijun Wu for 2D7-PE.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. A RANTES, MIP-1a, MIP-1b receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atchison R E, Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Franci C, Digilio L, Charo I F, Goldsmith M A. Multiple extracellular elements of CCR-5 and HIV-1 entry: dissociation from response to chemokines. Science. 1996;274:1924–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berson J F, Long D, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Jirik F R, Doms R W. A seven-transmembrane domain receptor involved in fusion and entry of T-cell-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains. J Virol. 1996;70:6288–6295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6288-6295.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieniasz P D, Fridell R A, Aramori I, Ferguson S S G, Caron M C, Cullen B R. HIV-1-induced cell fusion is mediated by multiple regions within both the viral envelope and the CCR5 co-receptor. EMBO. 1997;16:2599–2609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleul C C, Wu L, Hoxie J A, Springer T A, Mackay C R. The HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are differentially expressed and regulated on human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1925–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brelot A, Heveker N, Pleskoff O, Sol N, Alizon M. Role of the first and third extracellular domains of CXCR4 in human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor activity. J Virol. 1997;71:4744–4751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4744-4751.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesebro B, Buller R, Portis J, Wehrly K. Failure of human immunodeficiency virus entry and infection in CD4-positive human brain and skin cells. J Virol. 1990;64:215–221. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.215-221.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard G, Sodroski J. The b-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;86:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in co-receptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1 infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalgleish A G, Beverly P C L, Clapham P R, Crawford D H, Greaves M F, Weiss R A. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–766. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng H K, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, DiMarizio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng H K, Unutmaz D, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R. Expression cloning of new receptors used by simian and human immunodeficiency viruses. Nature. 1997;388:296–302. doi: 10.1038/40894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimitrov D S, Broder C C, Berger E A, Blumenthal R. Calcium ions are required for cell fusion mediated by the CD4–HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein interaction. J Virol. 1993;67:1647–1652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1647-1652.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doranz B, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic, primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3 and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;86:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dougherty D A. Cation-π interactions in chemistry and biology: a new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr and Trp. Science. 1996;271:163–168. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huanh Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragic, T., A. Trkola, S. W. Lin, K. A. Nagashima, F. Kajumo, L. Zhao, W. C. Olson, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, G. P. Allaway, T. P. Sakmar, J. P. Moore, and P. J. Maddon. Amino-terminal substitutions in the CCR5 coreceptor impair gp120 binding and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J. Virol. 72:279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Farzan M, Choe H, Martin K, Marcon L, Hofmann W, Karlsson G, Sun Y, Barrett P, Marchand N, Sullivan N, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. Two orphan seven-transmembrane segment receptors which are expressed in CD4-positive cells support simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:405–411. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane G protein coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gendelman H E, Orenstein J M, Martin M A, Ferrua C, Mitra R, Phipps T, Wahl L A, Lane H C, Fauci A S, Burke D S, Skillman D R, Meltzer M. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1428–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrowe G, Cheng-Mayer C. Amino acid substitutions in the V3 loop are responsible for adaptation to growth in transformed T-cell lines of a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 1995;210:490–494. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klatzmann D, Champagne E, Chamaret S, Gruest J M, Guetard D, Hercend T, Gluckman J C, Montagnier L. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature. 1984;312:382–385. doi: 10.1038/312767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu R T, Merrill J E, Vinters H V, Chen I S Y. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science. 1987;236:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.3646751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao F, Alkhatib G, Peden K W C, Sharma G, Berger E A, Farber J M. STRL33, a novel chemokine receptor-like protein, functions as a fusion cofactor for both macrophage-tropic and T cell line-tropic HIV-1. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2015–2023. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, MacDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–378. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maddon P J, Dalgleish A G, McDougal J S, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDougal J S, Kennedy M S, Sligh J M, Cort S P, Mawle A, Nicholson J K A. Binding of HTLV II/LAV to T4 T-cells by a complex of the 110K viral protein and the T4 molecule. Science. 1986;231:382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.3001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paxton W A, Martin S R, Tse D, O’Brien T R, Skurnick J, VanDevanter N L, Padian N, Braun J F, Kotler D P, Wolinsky S M, Koup R A. Relative resistance to HIV-1 infection of CD4 lymphocytes from persons who remain uninfected despite multiple high-risk sexual exposure. Nat Med. 1996;2:412–417. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Picard L, Simmons G, Power C A, Meyer A, Weiss R A, Clapham P R. Multiple extracellular domains of CCR-5 contribute to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry and fusion. J Virol. 1997;71:5003–5011. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5003-5011.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rucker J, Samson M, Doranz B J, Libert F, Berson J F, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Broder C C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. Regions in the β-chemokine receptors CCR-5 and CCR-2b that determine HIV-1 cofactor specificity. Cell. 1996;87:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samson M, Labbe O, Mollereau C, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a new CC-chemokine receptor gene, CC CKR-5. Biochemistry. 1996;11:3362–3367. doi: 10.1021/bi952950g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C M, Saragosti S, Mapoumeroulie C, Cogniaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Burtonboy G, Georges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistence to HIV-1 infection of Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CKR5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata R, Hoggan M D, Broscius C, Englund G, Theodore T S, Buckler-White A, Arthur L O, Israel Z, Schultz A, Lane H C, Martin M A. Isolation and characterization of a syncytium-inducing macrophage/T-cell line-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate that readily infects chimpanzee cells in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1995;69:4453–4462. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4453-4462.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons G, Wilkinson D, Reeves J D, Dittmar M T, Beddows S, Weber J, Carnegie G, Desselberger U, Gray P W, Weiss R A, Clapham P R. Primary, syncytium-inducing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates are dual-tropic and most can use either Lestr or CCR5 as coreceptors for virus entry. J Virol. 1996;70:8355–8360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8355-8360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strizki J M, Turner J D, Collman R G, Hoxie J, González-Scarano F. A monoclonal antibody (12G5) directed against CXCR-4 inhibits infection with the dual-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate HIV-189.6 but not the T-tropic isolate HIV-1HxB. J Virol. 1997;71:5678–5683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5678-5683.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeuchi Y, Akutsu M, Murayama K, Shimizu N, Hoshino H. Host range mutant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: modification of cell tropism by a single point mutation at the neutralization epitope in the env gene. J Virol. 1991;65:1710–1718. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1710-1718.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon P J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu L, LaRosa G, Kassam N, Gordon C J, Heath H, Ruffing N, Chen H, Humblias J, Samson M, Parmentier M, Moore J P, Mackay C R. Interaction of chemokine receptor CCR5 with its ligands; multiple domains for HIV-1 gp120 binding and a single domain for chemokine binding. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]