Abstract

Widespread fear among immigrants from hostile 2016 presidential campaign rhetoric decreased social and health care service enrollment (chilling effect). Health care utilization effects among immigrant families with young children are unknown. We examined whether former President Trump's election had chilling effects on well-child visit (WCV) schedule adherence, hospitalizations, and emergency department (ED) visits among children of immigrant vs US-born mothers in 3 US cities. Cross-sectional surveys of children <4 years receiving care in hospitals were linked to 2015–2018 electronic health records. We applied difference-in-difference analysis with a 12-month pre/post-election study period. Trump's election was associated with a 5-percentage-point decrease (−0.05; 95% CI: −0.08, −0.02) in WCV adherence for children of immigrant vs US-born mothers with no difference in hospitalizations or ED visits. Secondary analyses extending the treatment period to a leaked draft of proposed changes to public charge rules also showed significantly decreased WCV adherence among children of immigrant vs US-born mothers. Findings indicate likely missed opportunities for American Academy of Pediatrics–recommended early childhood vaccinations, health and developmental screenings, and family support. Policies and rhetoric promoting immigrant inclusion create a more just and equitable society for all US children.

Keywords: well-child care, public charge, 2016 election, health care utilization, immigrant families

Introduction

One in 4 children in the United States has at least 1 immigrant parent.1 These immigrant and mixed-status families face challenges in accessing health care, ranging from language and cultural alignment, to coverage gaps and cost, to racism and discrimination.2–4

Threats to immigrant safety and immigration status can affect access to health care, care-seeking, and utilization.5 Both state and federal policies can influence the social atmosphere and willingness of immigrants to seek assistance.6–8 Depending on the state, restrictive and punitive policies may determine whether they qualify for health care coverage9 and whether accessing social services puts their immigration status at risk.10 Complex rules create confusion and stress for health care staff and immigrant patients.11 Thus, immigrants who are affected by rules governing eligibility for Medicaid or other programs as well as those who are not directly affected may avoid seeking assistance or utilizing health care rather than risk potential immigration sanctions, including deportation for themselves or family members.

This phenomenon—avoiding social services or health care due to immigration status–related fear—is known as the “chilling effect.” Policymakers, researchers, and advocates have long been aware of the potential for policies to create chilling effects.12 For instance, in the 1990s, the federal government enacted sweeping policy changes known as “welfare reform,” including restrictions on immigrant eligibility, which ultimately barred otherwise eligible legal permanent residents (LPRs) from Medicaid and food stamps (now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]) for their first 5 years in the United States. A study at the time demonstrated that the law had no effect on single, US-born mothers’ Medicaid enrollment, but increased uninsurance among single immigrant mothers and their children.13

Renewed attention to chilling effects arose during the 2015–2016 presidential campaign, when Donald Trump used dehumanizing and racist language about immigrants, which was amplified in the press.14 News reports indicated increased concern about social and health care service access and enrollment among immigrant and mixed-status households, especially after Trump won the election.15–19 Following through on threats, after the inauguration, the Trump Administration dramatically increased anti-immigrant migration policies20,21 and immigration enforcement, especially in the interior of the country.22,23

In the same period, late January 2017, a draft Executive Order was leaked to the press that indicated a dramatic expansion to longstanding policies defining “public charge,” a concept that guides the consideration of public benefit participation and other factors for immigrants applying for LPR status.24,25 A person is deemed a public charge if judged to be primarily dependent on the government, which can be grounds for denying the LPR application. Although not ultimately adopted in its leaked form, the leak of the proposed public charge rule change received substantial media coverage, generating concerns about chilling effects and health consequences associated with fear of accessing public health services.24,26–28

One potential serious concern attending to the likely chilling effects produced by the 2016 presidential election is that they might lead to decreased utilization of health care and other critical services among immigrant families. If the strident anti-immigrant rhetoric of the campaign, which was manifest early in the Trump presidency in the leak of the proposed public charge rule change, caused families not to participate in Medicaid or other programs or to eschew services if already enrolled, 1 serious consequence might be a decline in health care utilization.

Indeed, a study of immigrant adults in California demonstrated decreased adult emergency department (ED) usage linked to negative rhetoric common during the campaign and following Trump's election.18 Among Latina women, the 2016 election was also associated with higher than expected numbers of preterm births.29 For school-age children in Baltimore, Trump's presidential campaign was followed by a decrease in primary care visits and increased ED visits for undocumented, Medicaid-ineligible children compared with Medicaid-eligible children.16 Finally, the leaked public charge draft was associated with delayed prenatal Medicaid enrollment among pregnant immigrant women in New York and lower infant birth weight.30

To date, however, no study has examined whether the chilling effects produced by the Trump election have affected the health care utilization of young children. Indeed, the study of Baltimore children specifically excluded younger children because of the complexity of accounting for the changing frequency of well-child visits (WCVs) in the first 3 years of life. Studying health care among young children is important for several reasons. Families with young children, particularly families of color and with immigrant members, are more likely than those with older children to have low incomes and, consequently, have difficulty accessing and affording health care, food, and housing.2,31–33 Birth to age 4 years is a uniquely sensitive developmental period of rapid body and brain growth that establishes the foundation for a child's future physical, socioemotional, and cognitive health, and school readiness.34 Frequent contact with the health care system is expected and encouraged in early childhood. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends 12 WCVs (Appendix Exhibit A27), with specified preventive screenings and assessments, in the first 3 years of life and annual checkups thereafter.35

Several studies have explored WCV schedule adherence, vital to optimal early childhood health and development.36–39 Among young, commercially insured children in Hawaii, missed WCVs and low continuity of care were associated with increased risk of ambulatory-care–sensitive hospitalizations.36 A 20-state study of families with low incomes found that of all WCVs, toddler and preschool WCVs were most commonly missed.39 Yet, there is little research on key national policy events and associations with WCVs among immigrant and US-born parents with the youngest children. It is important to document whether and to what degree the election differentially affected WCV adherence among children of immigrant and US-born parents to guide practices to ensure health care for all young children.

Our aims were to examine whether Trump's election had a chilling effect on (1) adherence to the WCV schedule and (2) the number of ED visits and hospitalizations among young children of immigrant compared with US-born parents. We hypothesized that, due to a chilling effect, following the election, immigrant parents might be afraid to continue WCVs and thus adherence to the overall schedule and receipt of specific WCVs would drop. Concurrently, rates of pediatric ED visits and hospitalizations would rise as families avoided preventive care and sought care only when children were very sick. We hypothesized that no such change would be detectable for children of US-born parents. Additionally, and acknowledging the proximity of the leak of the proposed public charge rule change soon after the election, we conducted secondary analyses to test the combined impact of the election and leaked draft of the public charge rule on these same outcomes.

Data and methods

Data source and population

This study's sample was identified from children enrolled in the ongoing Children's HealthWatch Study, a cross-sectional, sentinel surveillance, survey-based study of children younger than 4 years of age whose caregivers sought care for them in hospital settings. Surveys were conducted in English or Spanish in either pediatric EDs or hospital-based primary care clinics in 3 US cities (Boston, MA; Minneapolis, MN; and Little Rock, AR). Informed consent included consent to access the child's electronic health record (EHR). Survey responses were linked to the young child's EHR repository data covering the period 2015–2018, which included inpatient, ED, and outpatient visits and corresponding child ages, visit dates, and diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions [ICD-9 and 10, respectively]).40 The study received institutional review board approval.

Measures

The Children's HealthWatch survey included information on children's health insurance, caregivers’ educational attainment, and marital status. The birth mothers’ race and ethnicity were self-identified using questions from the US Census, asking separately about Latina/Hispanic heritage and race, and categorized as Latina (all races), Black (non-Latina), White (non-Latina), and other/multiple races (non-Latina). Maternal nativity was identified by country of birth (US/territories or other) to form 2 groups—US-born and immigrant—following previous research.19,31 Household employment was defined by report of 1 or more employed household members.

Health care utilization pattern

We developed a measure to represent children's outpatient health care utilization pattern by first creating variables that determined whether the child had any visits in 6-month age ranges and another to ascertain for how many months in the specific range children returned for a visit. Together, these allowed us to examine how many visits the children had over time in relation to their first visit (sample entry). Five categories resulted, as follows: (1) consistent utilization; (2) inconsistent utilization; (3) early utilization only (seen again within 1 y but never thereafter); (4) sample dropouts who entered but were never seen again; and (5) early utilization, left, and returned. Exploration of children's health care utilization pattern and secondary analyses excluding dropouts helped to examine whether children's data were missing at random (Appendix Exhibits A12-3&4 and A20-3&4).41

Outcome variables

Well-child visit adherence measures

A visit was coded a WCV if any of the outpatient diagnosis codes for that visit matched standard WCV ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes (V20.2, V20.31, V20.32, Z00.110, Z00.111, Z00.121, Z00.129). Building on Tom et al.'s methods,36 we created a “strict adherence” variable that accounted for the differing entry ages of children with any outpatient visit (WCV or not) into the EHR sample by comparing the recommended number of WCVs for their age during the study period with their actual number of WCVs. Children with the appropriate number of visits for their age were coded as adherent (Appendix Exhibit A27). For example, a child entering the sample at age 2 years and 3 months (27 mo) would be expected to have 2 WCVs in the following year. That child would be adherent if visits occurred during the child's 30th and 36th month (indicated WCV ages).

We also assessed whether results reported below were sensitive to our definition of WCV adherence with a more flexible and real-life adherence measure. “Flexible adherence” was calculated similarly to “strict adherence” but with a buffer period around each visit's timing, such that a WCV received in that buffer period (1 mo in the first year of life, 2 mo in the second year, and 3 mo in the third year) would still count as the child being adherent to the WCV schedule for that age. We also tested a third approach to WCV adherence. “Detailed adherence” was a binary indicator for whether patients attended each individual WCV rather than examining whether they attended all visits.

Hospitalizations

This measure counted all hospitalizations for each child during periods before and after the 2016 election, coded as a dichotomous indicator of any vs no hospitalizations for each of these 2 time periods.

Emergency department visits

We used a dichotomous indicator for whether a child used an ED for each of the 2 time periods.

Statistical methods

We described child and family characteristics comparing children of immigrant vs US-born mothers, using chi-square and t-tests, as appropriate. Our primary analyses were difference-in-difference (DiD) models, which examined whether any changes in WCV adherence, hospitalizations, or ED visits after the 2016 election were more pronounced among children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers. For the DiD analysis, we compared health care utilization in the year prior to the November 8, 2016, election with the year following. Following a standard approach,42 we specified our DiD model by including in a regression an interaction term (DiD estimator) between maternal nativity (the treatment variable) and a variable (time, measured in days) indicating whether the observation was in the pre- or postelection period (ie, maternal nativity × time).

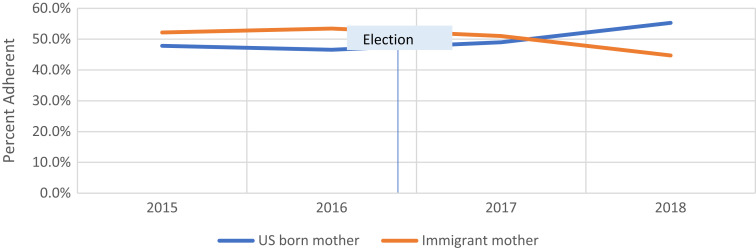

A primary assumption of DiD models is that trends in outcome measures are parallel prior to treatment. In our case, we assumed that parents’ desire to access health care did not vary by immigration status. Thus, to test the parallel trend assumption that health care utilization slopes between immigrant (treated) and US-born (controls) were the same before November 8, 2016, we applied linear regression in the year before election day, including an interaction term between the date of the visit and maternal nativity, and adjusting for covariates (below). Interaction term coefficients were not significant, suggesting no violation of the parallel trends assumption (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of former President Trump's election on well-child visits (flexible adherence) among immigrant compared with US-born families in the post-period, 2015–2018. Source: Authors’ analysis of Children's HealthWatch data, 2015–2018.

Analyses were adjusted for research site (state of residence), child insurance status, maternal race/ethnicity, caregiver marital status and educational attainment, household employment, and child age at the beginning of the pre-period. Analyses of strict and flexible adherence also included child health care utilization pattern as a covariate. For detailed adherence, an indicator allowing multiple observations for each child in the pre and post periods, we adjusted for covariates enumerated above plus fixed effects for each WCV, and the interaction between the post-period and treatment. Last, as a second complementary set of analyses, we explored all measures detailed above with an extended treatment period from election day through to the leak date of the draft public charge rule change in January 2017 (November 8, 2016–January 23, 2017), acting as an additional “intervention.” Because the inauguration was a confirmation of the election results, we chose not to consider the inauguration as a separate treatment but note that this expanded treatment period also contains President Trump's January 20th, 2017, inauguration.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses: (1) stratifying DiD analyses by age groups at sample entry (children <2 y, 2–4 y, ≥5 y), (2) excluding children who dropped out of the sample after a single health care visit (dropouts), (3) stratifying by immigrant mothers’ duration of residence in the United States, and (4) testing a triple DiD to explore differences by race/ethnicity with the interaction term: time × nativity × race/ethnicity (Appendix Exhibits A9-3&4; A10-3&4; A11-3&4; A12-3&4; A13-3&4; A16-3&4; A17-3&4; A18-3&4; A20-3&4; A21-3&4).

Study strengths and limitations

This study's strengths include its large, longitudinal, multistate design and focus on a racially and geographically diverse sample of families with a difficult-to-reach population of young children who have access to health care. The study uses sentinel sampling for the initial survey. The sentinel sample is both a strength and a limitation as a dynamic form of data collection designed to signal early trends and identify and monitor policy effects and disease burdens before they become widely prevalent. Thus, it helps identify emerging health impacts promptly and as they develop over time, so timely interventions can be developed.43,44 Linked longitudinal data available through the EHR provide a unique opportunity to track children's health care utilization over time in combination with a rich understanding of their families’ social context.

Study limitations include the potential for sample selection bias, as participants were caregivers of young children seeking health care in EDs or primary care clinics in 3 cities, which limits the generalizability of our findings. In addition, while our sample reflected the populations served by the particular EDs and other primary care settings in the 3 Children's HealthWatch cities, it was not representative of the population of families in the United States. For example, Asian mothers are underrepresented, particularly among the subgroup of immigrant families, where they represent a large share of the national population45 and those with public health insurance coverage are overrepresented in our sample (86% vs 35.9% of children in the US population).46 Arkansas uniquely expanded Medicaid by using Medicaid dollars to support private insurance; therefore, some children with private insurance may have Medicaid-funded coverage. Our analyses are, therefore, likely a conservative estimate of the true impact of the election and the leaked public charge rule.

Lack of generalizability from the sampling is offset by the availability of detailed data. Further, as noted above, a key advantage of the sentinel study design is the ability to track emerging trends in public health, which made it possible to investigate possible chilling effects among a group of families that are often considered hard to reach and are underrepresented in many national studies. Thus, while future research should seek to replicate these findings in a national sample, our findings—which speak to chilling effects among a vulnerable group of American families—are important.

In addition, a critical element of our study design is the comparison of outcomes between children from immigrant and nonimmigrant families. However, the paper considers only mothers’ nativity for classifying immigrant families, and thus might misclassify families where other adults are immigrants. The inclusion of these families in our comparison group would attenuate any estimate of chilling effects, and thus we consider the results reported below to be underestimates.

Last, the EHR dataset was not collected for research but rather in clinical care and thus data missing from the dataset may or may not be missing at random; a related concern is data on children's health care use may be missing if they receive care in other locations. However, following recommendations on missing data in EHR data analysis,41 we examined children's health care utilization pattern by maternal nativity, race/ethnicity, and study period, and conducted sensitivity analyses to ensure robust results even when excluding children who dropped out. Critically, these results do not differ substantively from our main findings, lessening concern about bias due to children receiving care elsewhere.

Results

There were 50 119 visits included in the sample, representing 10 974 children (Table 1). Of those, 40.9% had immigrant mothers. A total of 13.7% of US-born vs 70.8% of immigrant mothers were Latina and 51.6% of US-born vs 25.1% of immigrant mothers were Black, non-Latina. The mean age at sample entry was 37.7 compared to 38.8 months for children of US-born and immigrant mothers, respectively. The majority of children were publicly insured: 82.4% vs 89.5% for children of US-born and immigrant mothers, respectively.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of children of immigrant and US-born mothers, 2015–2018.

| Overall, n (%) | US-born mothers, n (%) | Immigrant mothers, n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | ||||

| Pediatric visits | 50 119 | 27 458 (54.79) | 22 661 (45.21) | |

| Unique children | 10 974 | 6427 (58.57) | 4493 (40.94) | |

| Site | <.0001 | |||

| Boston | 16 545 (33.01) | 8411 (30.63) | 8134 (35.89) | |

| Little Rock | 19 240 (38.39) | 15 401 (56.09) | 3839 (16.94) | |

| Minneapolis | 14 334 (28.60) | 3646 (13.28) | 10 688 (47.16) | |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Mean (SD) age at sample entry, mo | 38.19 (33.78) | 37.65 (33.51) | 38.84 (33.10) | <.0001 |

| Mean (SD) age, mo | 50.01 (34.03) | 49.53 (33.81) | 50.58 (34.29) | .0003 |

| Health insurance | <.0001 | |||

| Public | 42 760 (85.65) | 22 577 (82.44) | 20 183 (89.54) | |

| No insurance | 2795 (5.60) | 1443 (5.27) | 1352 (6.00) | |

| Private | 4370 (8.75) | 3365 (12.29) | 1005 (4.46) | |

| Outpatient health care utilization pattern | ||||

| Consistent utilization | 702 (2.89) | 702 (2.56) | 748 (3.30) | <.0001 |

| Inconsistent utilization | 45 776 (91.33) | 24 889 (90.64) | 20 887 (92.17) | |

| Early utilization only | 1679 (3.35) | 1065 (3.88) | 614 (2.71) | |

| Sample entry only (dropouts) | 755 (1.51) | 513 (1.87) | 242 (1.07) | |

| Early utilization, left, and returned | 459 (0.92) | 289 (1.05) | 170 (0.75) | |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Mean (SD) age, y | 28.90 (6.33) | 27.42 (6.01) | 30.69 (6.24) | <.0001 |

| Education | <.0001 | |||

| Less than high school diploma | 13 395 (26.79) | 3967 (14.47) | 9428 (41.75) | |

| High school diploma | 17 453 (34.90) | 9649 (34.19) | 7804 (34.56) | |

| Education beyond high school | 19 157 (38.31) | 13 805 (50.34) | 5352 (23.70) | |

| Marital status | <.0001 | |||

| Single | 18 419 (36.79) | 13 521 (49.28) | 4898 (21.65) | |

| Married/partnered | 23 064 (46.07) | 9982 (36.38) | 13 082 (57.82) | |

| Separated/divorced | 8577 (17.13) | 3932 (14.33) | 4645 (20.53) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | |||

| Latina | 19 691 (39.60) | 3737 (13.73) | 15 954 (70.83) | |

| Black, non-Latina | 19 691 (39.60) | 14 040 (51.60) | 5651 (25.09) | |

| White, non-Latina | 8491 (17.07) | 8214 (30.19) | 277 (1.23) | |

| Other/multiple races | 1858 (3.74) | 1217 (4.47) | 641 (2.85) | |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| One or more employed in household | 20 740 (41.46) | 12 635 (46.11) | 8105 (35.83) | <.0001 |

Column percentages are shown. Source: Authors’ analysis of Children's HealthWatch data, 2015–2018.

Well-child visits

Pre-election trends were parallel (Figure 1). DiD analyses showed that Trump's election was associated with a 5-percentage-point decrease for both strict adherence (−0.05; 95% CI: −0.08, −0.02) and flexible adherence (−0.05; 95% CI: −0.08, −0.02) for children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers (Table 2). In the pre-election period, 53.6% of children of immigrant mothers were adherent. Thus, a 5-percentage-point decrease would equate to the percentage dropping to 48.6% (a 9% relative decrease).

Table 2.

Effect of former President Trump's election and leaked public charge draft: difference-in-difference results for well-child visit adherence, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits among children of immigrant and US-born mothers, 2015–2018.

| Difference-in-difference: 2016 election | Difference-in-difference: alternative treatment period 2016 election and leaked public charge draft | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-child visits | n | Coefficient | 95% CI | n | Coefficient | 95% CI | ||

| Strict adherence | ||||||||

| Immigrant × postelection | 10 291 | −0.05*** | −0.08 | −0.02 | 10 922 | −0.09*** | −0.12 | −0.05 |

| Flexible adherence | ||||||||

| Immigrant × postelection | 10 291 | −0.05*** | −0.08 | −0.02 | 10 122 | −0.08*** | −0.12 | −0.05 |

| Detailed adherence | ||||||||

| Immigrant × postelection | 7728 | −0.07*** | −0.09 | −0.05 | 7632 | −0.07*** | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| Hospitalizations | ||||||||

| Immigrant × postelection | 13 706 | −0.009 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 12 871 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| Emergency department visits | ||||||||

| Immigrant × postelection | 13 085 | 0.009 | −0.009 | 0.03 | 12 871 | 0.01 | −0.005 | 0.03 |

Models for strict adherence and flexible adherence adjusted for research site, maternal race/ethnicity, education, and marital status, any household employment, child health insurance, health care utilization pattern, and age at sample entry. Models for detailed adherence adjusted for research site, maternal race/ethnicity, education, and marital status, any household employment, child health insurance, age at sample entry, and fixed effects for each well-child visit. Models for hospitalizations and emergency department visits adjusted for research site, maternal race/ethnicity, education, and marital status, any household employment, child health insurance and age at sample entry. Source: Authors’ analysis of Children's HealthWatch data, 2015–2018.

***P ≤ 0.001.

Using the indicator for detailed adherence, we found that the election was associated with a 7-percentage-point (−0.07; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.05) decrease in WCVs for children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers (Table 2). Coefficients were negative and statistically significant for the 4-month, 12-month, 15-month, 24-month, and 48-month WCVs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of former President Trump's election: difference-in-difference results for detailed adherence by well-child visit schedule among children of immigrant and US-born mothers, 2015–2018.

| Difference-in-difference: 2016 election | Difference-in-difference: alternative treatment period 2016 election and leaked public charge draft | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-child visit schedule | n | Coefficient | 95% CI | n | Coefficient | 95% CI | ||

| Newborn | 465 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.18 | 418 | 0.02 | −0.15 | 0.19 |

| 1 Month | 948 | −0.05 | −0.15 | 0.04 | 894 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 |

| 2 Months | 878 | 0.10 | −0.003 | 0.19 | 809 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| 4 Months | 924 | −0.11* | −0.21 | −0.008 | 858 | −0.15** | −0.26 | −0.05 |

| 6 Months | 1067 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.03 | 1003 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.03 |

| 9 Months | 1076 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 1028 | −0.04 | −0.15 | 0.07 |

| 12 Months | 1158 | −0.10* | −0.20 | −0.005 | 1099 | −0.08 | −0.18 | 0.03 |

| 15 Months | 1102 | −0.12* | −0.22 | −0.03 | 1025 | −0.08 | −0.19 | 0.03 |

| 18 Months | 1258 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 1199 | −0.09 | −0.19 | 0.01 |

| 24 Months | 1307 | −0.17*** | −0.26 | −0.07 | 1262 | −0.16** | −0.26 | −0.06 |

| 30 Months | 1045 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.16 | 1007 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.18 |

| 36 Months | 1675 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 1642 | −0.03 | −0.12 | 0.05 |

| 48 Months/4 years | 1756 | −0.17*** | −0.25 | −0.10 | 1717 | −0.17** | −0.25 | −0.09 |

| 5 Years | 1765 | −0.07 | −0.15 | 0.02 | 1715 | −0.09* | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| 6 Years | 1675 | −0.09 | −0.18 | 0.004 | 1597 | −0.08 | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| 7 Years | 1499 | −0.08 | −0.18 | 0.02 | 1456 | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.04 |

| 8 Years | 1172 | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.10 | 1144 | −0.04 | −0.15 | 0.08 |

| 9 Years | 660 | −0.17 | −0.36 | 0.02 | 639 | −0.16 | −0.34 | 0.02 |

| 10 Years | 246 | −0.05 | −0.45 | 0.34 | 240 | −0.11 | −0.47 | 0.26 |

| 11 Years | 58 | Insufficient sample size | 55 | Insufficient sample size | ||||

| 12 Years | 5 | Insufficient sample size | 5 | Insufficient sample size | ||||

Models for detailed adherence adjusted for research site, maternal race/ethnicity, education, and marital status, any household employment, and child health insurance. Source: Authors’ analysis of Children's HealthWatch data, 2015–2018.

*P = 0.05, **P = ≤0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

Hospitalizations and emergency department visits

DiD interaction terms for children's hospitalizations and ED visits were not significant (hospitalizations: −0.01 [95% CI: −0.03, 0.01]; ED visits: 0.009 [95% CI: −0.009, 0.03]) (Table 2).

Extended treatment period

In secondary analyses using the alternative treatment period extending from the election to the leaked draft, results for all measures of adherence were strengthened (Table 2). DiD analyses showed that, for children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers, Trump's election and the leaked draft were associated with decreases of 9 percentage points (−0.09; 95% CI: −0.12, −0.05) for strict adherence, 8 percentage points (−0.08; 95% CI: −0.12, −0.05) for flexible adherence, and 7 percentage points (−0.07; 95% CI: −0.09, −0.05) for detailed adherence. Similarly, the election and leaked draft were associated with decreases of 15 percentage points for the 4-month WCV (−0.15; 95% CI: −0.26, −0.05), 16 percentage points for the 24-month WCV (−0.16; 95% CI: −0.26, −0.06), 17 percentage points for the 48-month WCV (−0.17; 95% CI: −0.25, −0.09), and 9 percentage points for the 60-month WCV (−0.09; 95% CI: −0.18, −0.01) (Table 3). Among children in the relevant age range, 83.2% of children of immigrants in the pre-period received their 4-month WCV; thus, a drop of 15 percentage points equates to the percentage dropping to 68.2%. DiD coefficients for children's hospitalizations and ED visits were not significant (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses were consistent with main and secondary analyses for children younger than 2 years and with exclusion of dropouts; other analyses were not significant (Appendix Exhibits A16-3&4 and A20-3&4).

Discussion

We found a significant decrease in adherence to the WCV schedule across all 3 measures of WCVs for children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers after Trump's election. Secondary analyses extending the treatment period to the date of the leaked draft of the public charge rule showed greater decreases in adherence for all measures. In contrast to other studies’ findings of increased pediatric ED visits,16 we found no differences in hospitalizations and ED visits among children of immigrant compared with US-born mothers.

Trump's election followed a period of intensely negative and sometimes violent language about immigrants.47,48 This study's findings provide further evidence that this atmosphere may have precipitated a chilling effect among immigrant and mixed-status families, leading them to avoid accessing WCVs. The consequences of missing WCVs could be profound, as children receive vaccines for both personal and community well-being, and are screened for physical well-being and developmental milestones, and parents have opportunities to ask questions and receive guidance on caring for their children.39,49 Children screening positive for developmental delays or other health problems can be referred for further evaluation and intervention to resolve or mitigate future health problems. Moreover, other referrals for families can be identified, from behavioral health to basic needs supports. Thus, if children of immigrants missed WCVs, health and development impacts of pre-existing inequities in income and access to resources could be compounded.

Null findings for changes in pediatric hospitalization and ED visits were counter to our expectation of increased acute health care utilization among immigrant families. One possible explanation may be that the relative infrequency of hospitalizations and ED visits, compared with WCVs, required a change in behavior too extreme to detect in this age range. It is also possible that there was a chilling effect, such that, even if need increased, parents still may not feel safe accessing EDs. Unlike other studies, we did not have an immigration status measure and thus could not identify parents who were undocumented or had temporary status, groups most likely to experience the chilling effect. However, other studies have shown that even immigrants with permanent status (eg, LPRs), who theoretically need not worry about accessing acute health care, fear accessing health care for immigration reasons.7,18 Last, since we could not track where else parents received care, it may be that parents sought acute health care elsewhere, although our results did not change when we excluded sample dropouts.

Policy implications

After the 2016 election, anti-immigrant, restrictive, and often punitive policies made it more difficult for immigrants to migrate to the United States, access needed supports and services, adjust their status, and pursue a path to citizenship and their daily lives without arrest or deportation fears.19,50–54 In August 2019, the Trump Administration finalized and enacted a significant expansion to the public charge rule.55 The subsequent administration vacated the revised definition of public charge and released a final rule,56,57 clarifying a narrow public charge definition and making it more difficult for future administrations to swiftly change course,58 although recent efforts by Congress have attempted to undercut this.59 Work remains to regain immigrant communities’ trust.

Our study found that Trump's rhetoric and election were associated with household health care–seeking behavior, even without later concrete policy changes.15,26,50,60 Other studies examining Trump's candidacy declaration and early rhetoric found a similar relationship with declining adult and child health care utilization and public-assistance enrollment among immigrant and mixed-status families in SNAP, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), school meals, and Medicaid.8,15,16,18,19 It is in our national interest for all children and their families to be able to meet their basic needs, including for health care. Thus, it is important for candidates for public office, executive branch, legislative, health systems, and public health leaders to be mindful of the far-reaching physical and mental health consequences of the language and policy proposals our leaders choose to emphasize as well as the implementation of restrictive laws and policies.47,61

Conclusion

Words matter and have real-life consequences in campaigns and governance. After a presidential campaign of derogatory and often inflammatory language about immigrants and threats of policy change, Trump's election was associated with widespread negative impacts for immigrant communities, including decreasing the number of immigrant parents securing well-child care for their young children in 3 cities. Examining future changes to social service and health care law, regulation, and rhetoric through the lens of immigration policy and immigrant community impacts will create a more just and equitable society for all US children, regardless of their parents’ nativity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families who generously shared their time and information. They also thank Félice Lê-Scherban, PhD, MPH; Maureen Black, PhD; Sharon Coleman, MSPT, MPH; Ana Poblacion, PhD, MSc; and Richard Sheward, MPP for their feedback on this manuscript. They are grateful to Eduardo R. Ochoa, Jr, MD, and Megan Sandel, MD, MPH, for their assistance with clinical insights and data access. The authors acknowledge and thank the many funders of Children's HealthWatch for providing support for data collection that in turn made this analysis possible (www.childrenshealthwatch.org).

Contributor Information

Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, Health Law, Policy & Management, Boston University School of Public Health and Boston University Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, MA 02118, United States.

Daniel P Miller, Human Behavior, Research, and Policy, Boston University School of Social Work, Boston, MA, United States.

Julia Raifman, Health Law, Policy & Management, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02118, United States.

Diana B Cutts, Pediatrics, Hennepin Healthcare and University of Minnesota School of Medicine, MN, United States.

Allison Bovell-Ammon, Pediatrics, Boston Medical Center and Boston University Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States.

Deborah A Frank, Pediatrics, Boston Medical Center and Boston University Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States.

David K Jones, Health Law, Policy & Management, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02118, United States.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Health Affairs Scholar online.

Funding

This analysis had no specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

Please see ICMJE form(s) for author conflicts of interest. These have been provided as supplementary materials.

References

- 1. Migration Policy Institute . Children in U.S. immigrant families (by age group and state, 1990 versus 2019). Data Hub. 2019. Accessed February 21, 2021. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/children-immigrant-families

- 2.Evans EJ, Arbeit CA. What's the difference? Access to health insurance and care for immigrant children in the US. Int Migr. 2017;55(5):8–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morey BN. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):460–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewniak D, Krones T, Wild V. Do attitudes and behavior of health care professionals exacerbate health care disparities among immigrant and ethnic minority groups? An integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;70:89–98. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger Cardoso J, Scott JL, Faulkner M, Barros Lane L. Parenting in the context of deportation risk. J Marriage Fam. 2018;80(2):301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawes DP, McCrea AM. Give us your tired, your poor and we might buy them dinner: social capital, immigration, and welfare generosity in the American states. Polit Res Q. 2018;71(2):347–360. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perreira KM, Pedroza JM. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrants and their children. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):147–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DP, John RS, Yao M, Morris M. The 2016 presidential election, the public charge rule, and food and nutrition assistance among immigrant households. Am J Public. 2022;112(12):1738–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey SK, Cantor JC, Lloyd K. Immigrant health care access and the Affordable Care Act. Public Admin Rev. 2014;74(6):749–759. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page KR, Polk S. Chilling effect? Post-election health care use by undocumented and mixed Status families. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armin JS. Administrative (in)visibility of patient structural vulnerability and the hierarchy of moral distress among health care staff. Med Anthropol Q. 2019;33(2):191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer A. Welfare reform and immigrants: a policy review.. Immigrants, Welfare Reform, and the Poverty of Policy Reform, and the Poverty of Policy. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2004:21. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/200405_singer.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaushal N, Kaestner R. Welfare reform and health insurance of immigrants. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):697–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MYH. Donald Trump's false comments connecting Mexican immigrants and crime. The Washington Post. July 8, 2015. Accessed February 28, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2015/07/08/donald-trumps-false-comments-connecting-mexican-immigrants-and-crime/?utm_term=.ef4f86a2f029

- 15.Barofsky J, Vargas A, Rodriguez D, Barrows A. Spreading fear: the announcement of the public charge rule reduced enrollment in child safety-net programs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(10):1752–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwadiuko J, German J, Chapla K, Wang F, Venkataramani M. Changes in health care use among undocumented patients, 2014–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan T, Washburn DJ, Nimmons K, Duchicela D, Gurram A, Burdine J. Immigrant health access in Texas: policy, rhetoric, and fear in the Trump era. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez RM, Torres JR, Sun J, et al. Declared impact of the US President's statements and campaign statements on Latino populations’ perceptions of safety and emergency care access. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bovell-Ammon A, Ettinger de Cuba S, Coleman SM, et al. Trends in food insecurity and SNAP participation among immigrant families of US born young children. Children. 2019;6(4):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samari G, Catalano R, Alcalá HE, Gemmill A. The Muslim Ban and preterm birth: analysis of U.S. vital statistics data from 2009 to 2018. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113544. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuels EA, Orr L, White EB, et al. Health care utilization before and after the “Muslim Ban” executive order among people born in Muslim-majority countries and living in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2118216. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zamora L. Comparing Trump and Obama’s Deportation Priorities. 2017. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/comparing-trump-and-obamas-deportation-priorities/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramón C, Reyes L. Interior enforcement under the Trump administration by the numbers: part one. Removals. 2019. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/interior-enforcement-under-the-trump-administration-by-numbers-part-one-removals/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fix M, Capps R. Leaked draft of possible Trump executive order on public benefits would spell chilling effects for legal immigrants. 2017. Accessed February 28, 2021. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/leaked-draft-possible-trump-executive-order-public-benefits-would-spell-chilling-effects-legal

- 25.Makhlouf MD. The public charge rule as public health policy. Indiana Health Law Rev. 2019;16(2):177–210. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein H, Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Zuckerman S. One in seven adults in immigrant families reported avoiding public benefit programs in 2018. Washington, DC; 2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100270/one_in_seven_adults_in_immigrant_families_reported_avoiding_publi_7.pdf

- 27.Lind D. A leaked Trump order suggests he’s planning to deport more legal immigrants for using social services. Vox. 2017. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/1/31/14457678/trump-order-immigrants-welfare [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauslohner A, Ross J. Trump administration circulates more draft immigration restrictions, focusing on protecting U.S. jobs. The Washington Post. 2017. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/trump-administration-circulates-more-draft-immigration-restrictions-focusing-on-protecting-us-jobs/2017/01/31/38529236-e741-11e6-80c2-30e57e57e05d_story.html [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gemmill A, Catalano R, Casey JA, et al. Association of preterm births among US Latina women with the 2016 presidential election. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SS, Glied S, Babcock C, Chaudry A. Changes in the public charge rule and health of mothers and infants enrolled in New York state’s medicaid program, 2014–2019. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(12):1747–1756. 10.2105/AJPH.2022.307066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chilton M, Black MM, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity and risk of poor health among US-born children of immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang MN, Ettinger de Cuba S, Coleman SM, et al. Maternal place of birth, socioeconomic characteristics, and child health in US-born Latinx children in Boston. Acad Pediatr. 2019;20(2):225–233. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amuedo-Dorantes C, Arenas-Arroyo E, Sevilla A. Immigration enforcement and economic resources of children with likely unauthorized parents. J Public Econ. 2018;158:63–78. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black MM, Lutter CK, Trude ACB. All children surviving and thriving: re-envisioning UNICEF's conceptual framework of malnutrition. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e766–e767. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30122-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American Academy of Pediatrics . AAP schedule of well child care visits. Healthy Children, American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/health-management/Pages/Well-Child-Care-A-Check-Up-for-Success.aspx

- 36.Tom JO, Tseng C-W, Davis J, Solomon C, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Missed well-child care visits, low continuity of care, and risk of ambulatory care-sensitive hospitalizations in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(11):1052–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goyal NK, Rohde JF, Short V, Patrick SW, Abatemarco D, Chung EK. Well-child care adherence after intrauterine opioid exposure. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20191275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Needlman RD, Dreyer BP, Klass P, Mendelsohn AL. Attendance at well-child visits after reach out and read. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(3):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf ER, Hochheimer CJ, Sabo RT, et al. Gaps in well-child care attendance among primary care clinics serving low-income families. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20174019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization . ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; 2004. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haneuse S, Arterburn D, Daniels MJ. Assessing missing data assumptions in EHR-based studies: a complex and underappreciated task. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angrist J, Pischke J. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist's Companion. Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erwin P. Tracking the impact of policy changes on public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):653–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization. Immunization, vaccines and biologicals: sentinel surveillance. World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed March 4, 2019. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/sentinel/en/

- 45.Hanna M, Batalova J. Immigrants from Asia in the United States. 2021. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrants-asia-united-states-2020#:~:text= [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mykyta L, Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch L. Uninsured Rate of U.S. Children Fell to 5.0% in 2021. 2022. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/uninsured-rate-of-children-declines.html [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bovell-Ammon A, Ettinger de Cuba S, Cutts DB. Immigrant-inclusive policies promote child and family health. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(12):1735–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonn T. Trump's immigration rhetoric has ‘chilling effect’’ on families, says children's advocacy group director.’ The Hill. December 20, 2018. Accessed February 28, 2021. https://thehill.com/hilltv/rising/422371-childrens-advocacy-group-director-says-trumps-immigration-rhetoric-has-chilling

- 49. American Academy of Pediatrics . Well-child visits: parent and patient education. Bright Futures. 2021. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://brightfutures.aap.org/families/Pages/Well-Child-Visits.aspx

- 50.Wang RY, Campo Rojo M, Crosby SS, Rajabiun S. Examining the impact of restrictive federal immigration policies on healthcare access: perspectives from immigrant patients across an urban safety-net hospital. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022;24(1):178–187. 10.007/s10903-021-01177-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stillman S. The race to dismantle Trump's immigration policies. The New Yorker. February 2021. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/02/08/the-race-to-dismantle-trumps-immigration-policies

- 52.Guttentag L. Immigration Policy Tracking Project. 2021. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://immpolicytracking.org/home/

- 53. National Immigration Law Center . Analysis of Health and Benefit Provisions in the U.S. Citizenship Act. Washington, DC; 2021. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Health-and-Benefits-Provisions-in-USCA-analysis.pdf

- 54.Wolf R. Supreme Court allows Trump travel ban to take full effect. USA Today. December 4, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/12/04/supreme-court-allows-trump-travel-ban-take-full-effect/909797001/

- 55.Homeland Security Department. Final Rule on Public Charge Ground of Inadmissibility. US Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2019. Accessed December 20, 2022. https://www.uscis.gov/archive/final-rule-on-public-charge-ground-of-inadmissibility

- 56.Montoya-Galvez C. Biden administration stops enforcing Trump-era “public charge” green card restrictions following court order. CBS News. 2021. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/immigration-public-charge-rule-enforcement-stopped-by-biden-administration/

- 57.Kruzel J. Biden rescinds Trump's “public charge” rule. The Hill. March 2021. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/542860-biden-rescinds-trumps-public-charge-rule

- 58. Homeland Security Department . Public Charge Ground of Inadmissibility. 2022–18867. United States: US Citizenship and Immigration Service; 2022. p. 55472–55639. Accessed October 15, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/09/09/2022-18867/public-charge-ground-of-inadmissibility

- 59.Robertson N, Barrett T. Senate passes resolution to overturn Biden administration rule that does not penalize immigrants for receiving government benefits. CNN. 2023. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/17/politics/senate-vote-immigrants-government-benefits/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pelto DJ, Ocampo A, Garduño-Ortega O, et al. The nutrition benefits participation gap: barriers to uptake of SNAP and WIC among Latinx American immigrant families. J Community Health. 2020;45(3):488–491. 10.1007/s10900-019-00765-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson D, Shafer P. The Trump effect: postinauguration changes in marketplace enrollment. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2019;44(5):715–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.