Abstract

The major capsid protein of the pneumococcal phage Cp-1 that accounts for 90% of the total protein found in the purified virions is synthesized by posttranslational processing of the product of the open reading frame (ORF) orf9. Cloning of different ORFs of the Cp-1 genome in Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae combined with Western blot analysis of the expressed products led to the conclusion that the product of orf13 is an endoprotease that cleaves off the first 48 amino acid residues of the major head protein. This protease appears to be a key enzyme in the morphopoietic pathway of the Cp-1 phage head. To our knowledge, this is the first case of a bacteriophage infecting gram-positive bacteria that encodes a protease involved in phage maturation.

Viral proteases have been shown to play two general roles. Their first role is in a mechanism for gene expression in which a viral polyprotein (a precursor polypeptide) is proteolytically processed to yield the mature proteins. This was first suggested for the RNA-containing poliovirus (17) and has been described for positive-strand RNA viruses, retroviruses (3), and the DNA virus African swine fever virus (16). Host proteases frequently play a role in the maturation of viral proteins that eventually are associated with the viral envelope (3). The second general role for proteolytic processing is related to the viral morphogenesis in the activation of structural proteins to form mature virus particles. This is typical of DNA viruses and has been found to occur in the maturation of single proteins but not in that of polyproteins. For example, in bacteriophage T4, the more extensively studied phage, all but one of the prohead components are proteolytically cleaved (2). One or more proteases are usually involved in gene expression, and they can be of host or viral origin.

Streptococcus pneumoniae phages were first isolated in 1975 from throat swabs of healthy children (5, 10). They belong to three families that present a great variety of morphologies and that include lytic and temperate phages. Cp-1 is a family Podoviridae lytic phage, whose linear, double-stranded DNA (19,343 bp) has been completely sequenced recently (9). From comparative analyses of its genes and proteins, we concluded that Cp-1 displayed striking similarities to the Bacillus subtilis phage φ29, i.e., the products of 10 open reading frames (ORFs) of both phages share about 30% identity. These similar polypeptides include the gene product of orf9 of the Cp-1 genome, which is the precursor of the major head protein (gp9) (see below). Furthermore, bacteriophages Cp-1 and φ29 contain a terminal protein covalently linked to the 5′ ends of their DNAs (4) and replicate by an analog mechanism (8). On the contrary, both phages are host specific, present a different transcriptional organization, and, most likely, follow a different capsid assembly pathway (13). In terms of protein content, infective purified Cp-1 virions harbor a major head protein (gp9* [37 kDa]) that accounts for 90% of the total proteins. N-terminal analysis of gp9*, extracted from a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, demonstrated the cleavage of the first 48 amino acid residues from the primary product of orf9. Moreover, we have overexpressed the entire orf9 gene in Escherichia coli, and N-terminal analysis of its corresponding protein demonstrated that E. coli did not cleave the first 48 N-terminal amino acid residues of the Cp-1 major head protein. This result strongly suggested that the cleavage process was specific for the pneumococcal system (9). To localize the gene(s) involved in maturation of the major head protein of Cp-1, we have explored a variety of in vivo and in vitro experimental conditions, which allowed us to determine that the protease involved in this process is of viral origin.

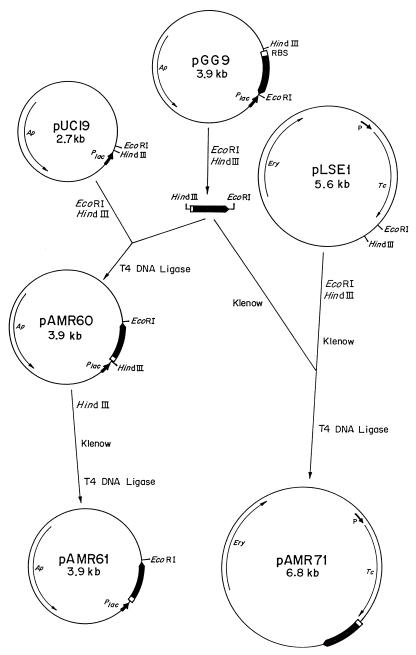

The bacteriophages, strains, and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. As a first step for studying the cleavage of the phage major head protein, a polyclonal antiserum against gp9*, isolated from an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, was prepared. On the other hand, the orf9 gene was cloned and expressed in E. coli and S. pneumoniae, in order to ensure the availability of the appropriate substrate in both bacterial hosts. Hence, we constructed two recombinant plasmids containing orf9: pAMR61, a derivative of pUC19, and pAMR71, a derivative of pLSE1 (a shuttle vector capable of replicating in S. pneumoniae as well as in E. coli), as shown in Fig. 1. The level of expression of orf9 from pAMR61 was very high, even in the absence of inducer, whereas its expression from pAMR71 was weaker in both bacterial systems, since it is expressed under the control of the tetracycline resistance gene.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and plasmids used in this study

| Bacteriophage, strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Inserta | ORF no.b | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophages | ||||

| Cp-1 | 12 | |||

| Dp-1 | 10 | |||

| Strains | ||||

| S. pneumoniae | ||||

| R6 | Wild type | Rockefeller University | ||

| R6st | Smr | Rockefeller University | ||

| M31 | ΔlytA | 15 | ||

| E. coli | ||||

| DH5α | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 ΔlacU169(φ80 lacZΔM15) | 14 | ||

| CC118 | Δlac X74 phoA Δ20 recA1 Rifr | 7 | ||

| MG1063 | F+ γδ (3X)::Tn1000 λ−recA56 | 6 | ||

| C600 | supE44 lacY1 F− | 14 | ||

| Plasmids | ||||

| pLSE1 | Eryr Tcr | 11 | ||

| pGG1 | pBR322 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in HindIII | 1449–10734 | 5–14 | This work |

| pGG2 | pUC18 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 9908–12716 | 15–17 | 9 |

| pGG6 | pUC18 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 6864–10734 | 11–14 | This work |

| pGG451 | pUC19 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 3622–8031 | 6–10 | This work |

| pGG1213 | pGG6 derivative, Apr, digested with StyI, and religated | 6864–9162 | 11–13 | This work |

| pAMR61 | pUC19 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 5395–6556 | 9 | 9 |

| pUCP12 | pUC18 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 8212–8828 | 12 | This work |

| pUCP13 | pUC18 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 8775–9165 | 13 | This work |

| pUCP14 | pUC18 derivative, Apr, carrying the insert cloned in SmaI | 9085–9996 | 14 | This work |

| pAMR71 | pLSE1 derivative, Eryr Tcr, carrying the insert cloned in EcoRI-HindIII | 5395–6556 | 9 | This work |

| pTNM13 | pGG6 derivative, Apr, with Tn1000 insert in orf13 | 6864–10734 | 11, 12, 14 | This work |

Coordinates of the Cp-1 DNA insert (accession no. Z47794).

Complete ORFs (orf5 to orf17) in the insert.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the construction of pAMR61 and pAMR71. Thin lines represent vector-derived sequences, and the thick black line represents orf9 encoding the major head protein of Cp-1. The white rectangle preceding orf9 indicates its ribosome binding site. P marks the promoter of the tetracycline resistance gene (Tc), and Plac marks that of the lacZ gene. Ap, ampicillin resistance gene; Ery, erythromycin resistance gene.

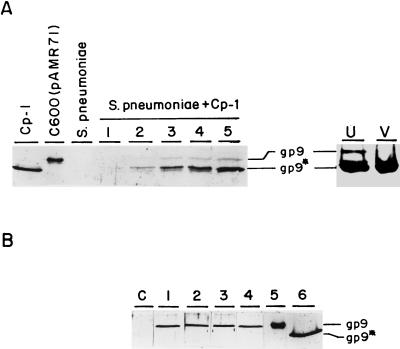

We have monitored the processing of the Cp-1 major head protein produced in vivo, by using lysates of Cp-1-infected pneumococcal R6st cells sampled at different times after infection and analyzing them by Western blotting. Figure 2A demonstrates that cleavage of gp9 is an extremely rapid process that takes place as soon as the protein is synthesized, although the proteolytic activity is not enough to hydrolyze all of the capsid proteins synthesized. Consequently, the proportions of both protein forms seems to be constant during infection. When the CsCl-purified virions were analyzed, only the processed protein was detected, whereas the bluish band of the lowest-buoyant-density band obtained in the CsCl gradient contained both the processed and intact forms of gp9 (Fig. 2A, lanes V and U, respectively). The upper band of the gradient appears to correspond to ghost particles, since they are composed of defective virions and debris of phage proteins that have not been packaged in mature virions and that do not contain DNA. These results suggested the inability of the intact protein to form infective virions.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of the major head protein of Cp-1 in different extracts. (A) Cp-1 corresponds to the Cp-1 virion; C600(pAMR71) extracts were prepared from E. coli; S. pneumoniae extracts were from uninfected cells; and lanes marked S. pneumoniae + Cp-1 contained extracts taken from Cp-1-infected cells at 40 (lane 1), 60 (lane 2), 80 (lane 3), 100 (lane 4), and 120 (lane 5) min after infection. On the right side are shown the results of analysis of the upper band (lane U) or the virion band (lane V) of a CsCl gradient of the Cp-1 lysate of S. pneumoniae (see text). (B) Extracts prepared from M31(pLSE1) (lane C), M31(pAMR71) (lane 1), UV-irradiated M31(pAMR71) (lane 2), mitomycin-treated M31(pAMR71) (lane 3), Dp-1-infected M31(pAMR71) (lane 4), C600(pAMR71) (lane 5), and the Cp-1 virion (lane 6). Samples were charged on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and detected with a polyclonal anti-gp9* serum. The positions of gp9 and its processed form, gp9*, are indicated.

We also tested, by Western blot assay, the size of the major head protein synthesized in S. pneumoniae M31 transformed with pAMR71. Figure 2B shows that the protein detected corresponds to the unprocessed form (lane 1). This result suggested that the protease was coded for either by the phage or by the host only under certain stress conditions. To check the latter hypothesis, we prepared several cultures of S. pneumoniae M31 treated with mitomycin, UV irradiated, or Dp-1 infected, Dp-1 being another pneumococcal phage with morphological and physiological properties completely unrelated to those of Cp-1 (5, 10). All of these concentrated extracts also gave the unprocessed form of gp9 (lanes 2, 3, and 4, respectively). Therefore, we concluded that, most likely, Cp-1 coded for the protease or, at least, for a factor which specifically induces the synthesis of a host protease.

As an additional step to test the phage origin of the protease, we analyzed the cleavage of the major head protein in E. coli cultures expressing different Cp-1 genes. The Cp-1 genome contains 29 ORFs, and 11 of the 29 putative proteins encoded by these ORFs exhibited high similarity to proteins of the φ29 phage (similarities ranging from 44 to 59%). Although comparative analysis allowed assignment of a putative functionality to these 11 ORF gene products, we were unable to recognize any sequence corresponding to identified proteases among these proteins (9). Further analysis of the other 18 ORFs led us to rule out the early genes, which normally code for proteins involved in replication or transcription regulation. Therefore, we focused our attention on genes encoding proteins that are expressed late and that had not already had a putative function ascribed (i.e., the proteins encoded by orf12 to orf16 and orf18).

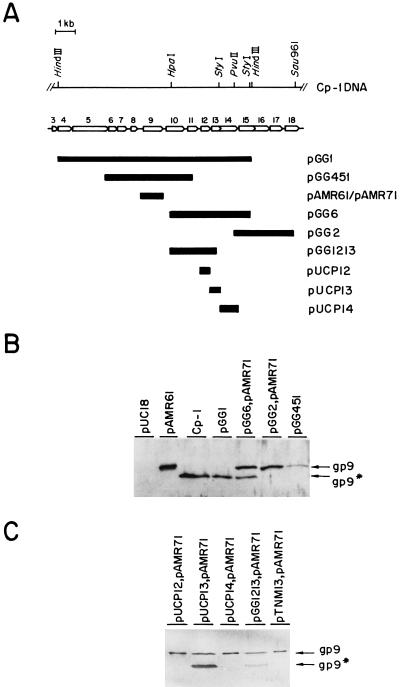

Figure 3A shows a partial map of Cp-1 DNA indicating the different ORFs and some of the recombinant plasmids constructed for sequencing analysis or to investigate the putative physiological role of these ORFs. All of these plasmids are able to replicate in E. coli and are compatible with pAMR71; therefore, it was possible to analyze the effect, in cis or in trans, of Cp-1 genes on gp9 synthesized by C600(pAMR71). Sonicated extracts from cultures transformed with the plasmids shown in Fig. 3A were subjected to Western blot analysis, and the results are presented in Fig. 3B. As expected, cell extracts from E. coli C600(pAMR71) (data not shown) or E. coli DH5α(pAMR61) showed only one band, which corresponded to the unprocessed gp9. However, the extracts prepared from DH5α(pGG1) exhibited a single band that corresponded to the 37-kDa cleaved major head protein. Plasmid pGG1 contains 10 complete ORFs, from orf5 to orf14, and parts of orf4 and orf15. On the contrary, the samples from C600(pAMR71, pGG2) or DH5α(pGG451) gave a single band corresponding to the nonprocessed form of gp9. Interestingly, in the case of C600(pAMR71, pGG6), the processed form of gp9 was observed, although the appearance of two bands may be considered somewhat striking compared with the result observed with DH5α(pGG1). Since the phage insert of pGG6, which contains orf11 to orf14, is completely included in pGG1, a possible explanation of the partial processing might be the different level of expression of the major head protein. It therefore seems plausible that the protease was capable of hydrolyzing, in E. coli, only a limited amount of the major head protein when this was synthesized in large amounts. All of these results indicated that the putative protease gene is probably encoded by orf12, orf13, or orf14.

FIG. 3.

Partial physical and genetic map of Cp-1 phage DNA and detection by Western blot analysis of the protease encoded by the Cp-1 genome. (A) The localizations of the phage DNA inserts present in several recombinant plasmids are represented by black bars. White arrows indicate the ORFs of the Cp-1 genome. (B) Western blot analysis of extracts prepared from E. coli transformed with the indicated plasmids. The gp9* protein from the Cp-1 virion is also shown. (C) Western blot analysis of extracts prepared from E. coli transformed with the indicated plasmids. Samples used for the experiments shown in panels B and C were analyzed with an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and detected with a polyclonal anti-gp9* serum. The positions of gp9 and its processed form, gp9*, are indicated.

To precisely ascribe the protease activity to an ORF of the remaining three candidates, we carried out several experiments. Transposon inactivation on pGG1 and pGG6, with Tn1000 according to the procedure described by Guyer (6), was performed to prepare a variety of insertionally inactivated genes. Sequence analysis of different clones revealed that only those isolates harboring an inactive ORF, orf12 or orf13, were incapable of cleaving the gp9 protein (e.g., the clone containing pTNM13 has orf13 interrupted) (Fig. 3C). To discard a polar effect on the activity of orf13, additional experiments were performed, and we found that only DH5α(pUCP13, pAMR71) cleaved the phage protein (Fig. 3C), with even a higher efficiency than that shown by C600(pAMR71, pGG6) (Fig. 3B), strongly suggesting that gp13 is the Cp-1 protease. To reinforce this conclusion, we mixed different extracts with that prepared from C600(pAMR71), and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min and subjected to Western analysis. Only the pUCP13-containing extract, but neither the pUCP12- nor the pUCP14-containing extract, was capable of processing the major head protein (data not shown).

The Cp-1 protease, encoded by orf13, has 104 amino acid residues, a deduced molecular weight of 11,868, and a theoretical pI of 5.8. This endoprotease does not contain the typical protease motifs and does not share any sequence similarity with other known proteases. Concerning the specificity of the cleavage, a great variety of recognizeable sequences have been described, both viral and host gene encoded, as being involved in the processing of different structural proteins of virions (2). The Cp-1 protease hydrolyzes the major head protein in the sequence RINH↓ATVP (5). Interestingly, the N-terminal sequence of the processed protein found in the virion (ATV) is identical to that reported for the N-terminal sequence of the T4 prohead IPIII protein, which is processed by the T4 gp21 endoprotease. However, the C-terminal sequence of the 48-amino-acid fragment released from Cp-1 gp9 does not reveal any similarity to that produced by the T4 protease (1).

Phage φ29 from B. subtilis appears to suffer proteolytic cleavage in the case of neck appendage proteins, and this processing occurs prior to assembly and not on the maturing particle. Nevertheless, the protease responsible for this process is encoded, most likely, by the host (18). A review of the literature indicates that Cp-1 gp13 represents a unique example of a protease coded for by a phage infecting gram-positive bacteria, and it is noteworthy that a bacteriophage with a relatively small size encodes its own protease to cleave the major head protein during the maturation process. The exact role of this protease in this process or in phage assembly has not been determined, and the availability of a mutant lacking the protease activity would be very useful. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the biochemical characteristics and regulatory aspects of the Cp-1 protease should require further investigation, although the studies described here represent the first attempt at defining the morphogenetic pathway of a pneumococcal bacteriophage.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. García, J. A. García, and J. L. García for valuable advice during the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank E. Cano and M. Carrasco for technical assistance and A. Hurtado, V. Muñoz, and M. Fontenla for the artwork.

This research was supported by grant PB93-0015-C02-01 from the DGICYT. A.C.M. was the recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the DGICYT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black L, Showe M. Morphogenesis of the T4 head. In: Mathews C K, Kulter E M, Mosig G, Berget P B, editors. Bacteriophage T4. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1983. pp. 219–245. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casjens S, Hendrix R. Control mechanisms in dsDNA bacteriophage assembly. In: Calendar R, editor. The bacteriophages. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1988. pp. 15–91. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty W G, Semler B L. Expression of virus-encoded proteinases: functional and structural similarities with cellular enzymes. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:781–822. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.781-822.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García P, Hermoso J M, García J A, García E, López R, Salas M. Formation of a covalent complex between the terminal protein of pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 and 5′-dAMP. J Virol. 1986;58:31–35. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.31-35.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García P, Martín A C, López R. Bacteriophages of Streptococcus pneumoniae: a molecular approach. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:165–176. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyer M S. Uses of the transposon γδ in the analysis of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1981;101:362–369. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manoil C, Beckwith J. TnphoA: a transposon probe for protein export signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8129–8133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martín A C, Blanco L, García P, Salas M, Méndez J. In vitro protein-primed initiation of pneumococcal phage Cp-1 DNA replication occurs at the third 3′ nucleotide of the linear template: a stepwise sliding-back mechanism. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:369–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martín A C, López R, García P. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence and functional organization of the genome of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage Cp-1. J Virol. 1996;70:3678–3687. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3678-3687.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonnell M, Ronda C, Tomasz A. “Diplophage”: a bacteriophage of Diplococcus pneumoniae. Virology. 1975;63:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronda C, García J L, López R. Characterization of genetic transformation in Streptococcus oralis NCTC 11427. Expression of pneumococcal amidase in S. oralis using a new shuttle vector. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;215:53–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00331302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronda C, López R, García E. Isolation and characterization of a new bacteriophage, Cp-1, infecting Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Virol. 1981;40:551–559. doi: 10.1128/jvi.40.2.551-559.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salas M. Phages with protein attached to the DNA ends. In: Calendar R, editor. The bacteriophages. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1988. pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sánchez-Puelles J M, Ronda C, García J L, García P, López R, García E. Searching for autolysin functions. Characterization of a pneumococcal mutant deleted in the lytA gene. Eur J Biochem. 1986;158:289–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simón-Mateo C, Andrés G, Viñuela E. Polyprotein processing in African swine fever virus: a novel gene expression strategy for a DNA virus. EMBO J. 1993;12:2977–2987. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Summers D F, Maizel J V., Jr Evidence for large precursor proteins in poliovirus synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:966–971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.3.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosi M E, Reilly B E, Anderson D L. Morphogenesis of bacteriophage φ29 of Bacillus subtilis: cleavage and assembly of the neck appendage protein. J Virol. 1975;16:1282–1295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.5.1282-1295.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]