Abstract

Objective

To investigate opioid prescribing trends and assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid prescribing in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs).

Methods

Adult patients with RA, PsA, axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA), SLE, OA and FM with opioid prescriptions between 1 January 2006 and 31 August 2021 without cancer in UK primary care were included. Age- and gender-standardized yearly rates of new and prevalent opioid users were calculated between 2006 and 2021. For prevalent users, monthly measures of mean morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day were calculated between 2006 and 2021. To assess the impact of the pandemic, we fitted regression models to the monthly number of prevalent opioid users between January 2015 and August 2021. The time coefficient reflects the trend pre-pandemic and the interaction term coefficient represents the change in the trend during the pandemic.

Results

The study included 1 313 519 RMD patients. New opioid users for RA, PsA and FM increased from 2.6, 1.0 and 3.4/10 000 persons in 2006 to 4.5, 1.8 and 8.7, respectively, in 2018 or 2019. This was followed by a fall to 2.4, 1.2 and 5.9, respectively, in 2021. Prevalent opioid users for all RMDs increased from 2006 but plateaued or dropped beyond 2018, with a 4.5-fold increase in FM between 2006 and 2021. In this period, MME/day increased for all RMDs, with the highest for FM (≥35). During COVID-19 lockdowns, RA, PsA and FM showed significant changes in the trend of prevalent opioid users. The trend for FM increased pre-pandemic and started decreasing during the pandemic.

Conclusion

The plateauing or decreasing trend of opioid users for RMDs after 2018 may reflect the efforts to tackle rising opioid prescribing in the UK. The pandemic led to fewer people on opioids for most RMDs, providing reassurance that there was no sudden increase in opioid prescribing during the pandemic.

Keywords: opioids, trend, RA, PsA, axial spondyloarthritis, SLE, OA, FM, COVID-19

Rheumatology key messages.

Opioid users’ trends stabilized after 2018 for RMDs—likely an effort to tackle rising opioid prescribing in the UK.

Fewer opioid users during the pandemic provide reassurance that there was no sudden increase in opioid prescribing in this period.

Fibromyalgia (≥35) and AxSpA (34–35) had the highest overall mean morphine milligram equivalents per day.

Introduction

The opioid epidemic has become a public health crisis affecting the USA and Canada over the past two decades [1, 2]. The UK has also shown an increasing trend of opioid prescribing, including for non-cancer chronic pain [3, 4]. Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are one of the most common indications for prescribed opioids, where pain management is often challenging [5]. Additionally, RMD patients may be vulnerable to opioid-related harms due to complex comorbidities, polypharmacy and immunosuppression. However, there has been limited evidence on opioid prescribing within different RMDs and how trends may have changed over time [6–8].

The COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020 and quickly impacted healthcare systems globally. The UK government commenced the first national lockdown on 26 March 2020 [9]. Diagnoses of many conditions were shown to have decreased substantially between March and May 2020 in a deprived UK population, indicating patients had difficulties accessing or were reluctant to attend the healthcare system [10]. In the USA, opioid-related overdose deaths became an emerging crisis accelerated by the pandemic [11]. The rebound of the epidemic of opioid overuse further raised a concern about the pandemic’s effect on opioid prescribing in RMDs, which had improved before the pandemic [12].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid prescribing in patients with different RMDs in the UK is unknown. The change in opioid prescribing for RMDs could be bidirectional. RMD patients may have had difficulties making an appointment with their general practitioners (GPs) during the pandemic due to difficulties in access [10] or had fear of virus exposure, and hence prescribing would decrease. Alternatively, opioid use could increase because elective-surgical interventions were cancelled during the pandemic or those already on opioids might take opioids continuously as they may miss opportunities to discuss effectiveness, deprescribing strategies or non-pharmacological alternatives. GPs may have altered their prescribing patterns of opioids, such as longer or more potent opioid prescriptions for effective pain control, to accommodate to COVID-19 restrictions during the pandemic. This study therefore aimed to evaluate (i) the trends of new opioid users and prevalent opioid users for RMDs between 2006 and 2021, (ii) changes in prescribing patterns such as opioid types and morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and (iii) the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid prescribing.

Methods

Study population

Data came from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a database of anonymized UK primary care electronic health records representative of the national population [13]. The study was approved by the CPRD’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (approval number: 20_000143).

This study included six of the most common RMDs. Three were inflammatory: RA, PsA and axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA); one was a connective tissue disease: SLE; and two were non-inflammatory: OA and FM. Patients aged ≥18 years with an RMD diagnosis and an opioid prescription in the CPRD between 1 January 2006 and 31 August 2021 were eligible for inclusion. Some patients had one or more RMD diagnoses and were studied in different cohorts separately. Individuals who had a cancer diagnosis within the 5 years before the opioid prescription were excluded (except non-melanoma skin cancer), as cancer patients may have different drug utilization patterns. Opioids prescribed up to 6 months before or any time after an RMD diagnosis were included in this study. New opioid users were defined as individuals who had a new episode of opioid use in a 2-year time window (i.e. no opioid prescriptions for 2 years before the date of the next prescription; Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online); prevalent opioid users were defined as patients who had an existing episode of opioid use, which could be intermittent or persistent use. Baseline characteristics (i.e. age and gender) were collected on the index date of the first opioid prescription within the study period. Disease history, including alcohol dependence, substance use disorder, depression and suicide/self-harm, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were identified using Read Codes in a 5-year look-back period before the opioid prescription. The CCI was presented in three categories: low 0, medium (1–3) and high (4+) scores.

Rates of new and prevalent opioid users

Yearly rates of new opioid users were calculated using individuals with a new episode of opioid use with an RMD per year as the numerator and eligible patients registered in CPRD per year as the denominator. The number of patients with a specific RMD registered in CPRD is unavailable, and the cohort and denominator derivation is described in Supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online. Yearly rates of prevalent opioid users were calculated by dividing the number of individuals with an existing episode of opioid use and with each respective RMD per year by the number of eligible patients registered in CPRD per year. Monthly rates of new and prevalent opioid users between 2015 and 2021 were also calculated. All outcomes and their definitions are summarized in Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online.

Prescribing patterns among new and prevalent opioid users

The opioid types prescribed for new and prevalent opioid users between 2006 and 2021 were evaluated. For each RMD, the proportion of each opioid medication was calculated by dividing the yearly number of new/prevalent opioid users who took a specific opioid by the yearly number of new/prevalent opioid users. Only the first opioid prescription of new users was included while all prescriptions in one year for prevalent users were considered. For prevalent opioid users, the number and duration of opioid prescriptions and MME/day were also studied. Prescriptions’ durations were estimated using a drug preparation algorithm [14], and the relevant decisions are described in Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online. For each RMD, the mean number of opioid prescriptions per month per prevalent opioid user was calculated by dividing the sum of the numbers of opioid prescriptions in a specific month among prevalent opioid users by the number of prevalent opioid users in that month. The mean duration of opioid prescriptions per month per prevalent opioid user was also computed using the same way as the mean number. We first calculated the mean MME/day per month for each prevalent user. For each RMD, monthly measures of MME/day were then obtained from the mean value of MME/day among prevalent users per month for a given RMD (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

Statistical analysis

Age- and gender-standardized rates for new/prevalent opioid users were obtained from crude rates and the UK population published by the Office for National Statistics using direct standardization. Change points in the trend were identified by looking at the points where the derivative (i.e. the rate of change) of the standardized rates crossed zero. When the derivative and its CIs dropped below zero, the respective time point was defined as a significant decreasing change point. If the derivative and the CIs increased over zero, the time point was regarded as an increasing change point.

To investigate potential changes in opioid prescribing during the pandemic, we determined monthly numbers of new and prevalent opioid users between 1 January 2015 and 31 August 2021. Monthly values were used to evaluate the change during the pandemic, and 2015 was chosen because of no significant change in opioid prescribing policy after 2015. To assess the changes in prescribing patterns, we further determined, for prevalent opioid users, monthly numbers of opioid prescriptions and their MME/day. We fitted negative binomial regression models for the number of new and prevalent opioid users and the number of opioid prescriptions, and a linear regression model for MME/day. In all models, we used a linear time effect, a binary lockdown indicator with a value equal to 0 before lockdown and an interaction term between time and lockdown indicator. The coefficient of the lockdown indicator () in combination with the coefficient of the interaction term () represents the difference in the model estimates of the response variable after lockdown from the model estimates of the response before lockdown. represents the change in the trend per month during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (Supplementary Fig. S3, available at Rheumatology online) [15]. The statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of this article or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Results

This study included 1 313 519 patients, including 36 932 RA patients, 12 649 PsA patients, 6811 AxSpA patients, 6423 SLE patients, 1 255 999 OA patients and 66 944 FM patients. Of these, 21 743 (58.9%) RA patients, 8403 (66.4%) PsA patients, 4371 (64.2%) AxSpA patients, 4431 (69.0%) SLE patients, 929 138 (74.0%) OA patients and 34 027 (50.8%) FM patients had one or more episodes of new opioid use in this study period. The baseline characteristics by RMD are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was highest in the RA cohort (60.5 [15.0] years) while the AxSpA cohort had the lowest mean age (49.0 [15.2] years). Women were over-represented in all RMDs, except for AxSpA with 32.4% of women. More than half had more than one RMD in each cohort, except that OA only had 5.3% with more than one RMD diagnosis. RA and SLE had a higher proportion of medium CCI scores (56.2% and 49.0%). FM had the highest proportion of patients who were diagnosed with depression (30.2%) and who intended to or had committed suicide or self-harm (4.3%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohorts by RMD

| RA | PsA | AxSpA | SLE | OA | FM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 36 932 | 12 649 | 6811 | 6423 | 1 255 999 | 66 944 |

| New users, % (n) | 58.9 (21 743) | 66.4 (8403) | 64.2 (4371) | 69.0 (4431) | 74.0 (929 138) | 50.8 (34 027) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 60.5 (15.0) | 51.7 (14.2) | 49.0 (15.2) | 52.5 (15.9) | 59.6 (17.3) | 49.9 (14.1) |

| Age group, % (n) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 1.2 (425) | 2.1 (262) | 3.9 (262) | 3.5 (222) | 3.4 (43 110) | 3.3 (2236) |

| 25–34 | 4.5 (1668) | 9.9 (1257) | 15.5 (1052) | 10.0 (643) | 6.3 (79 612) | 11.0 (7368) |

| 35–44 | 9.8 (3613) | 19.6 (2483) | 22.1 (1506) | 19.4 (1247) | 10.1 (126 361) | 20.9 (13 985) |

| 45–54 | 17.7 (6531) | 26.4 (3345) | 22.7 (1549) | 23.1 (1481) | 16.5 (207 273) | 28.3 (18 967) |

| 55–64 | 24.6 (9090) | 23.2 (2928) | 19.1 (1301) | 20.4 (1307) | 21.8 (273 152) | 21.9 (14 664) |

| 65–74 | 23.4 (8640) | 13.0 (1643) | 11.1 (757) | 14.0 (899) | 20.7 (259 435) | 9.7 (6507) |

| 75–84 | 15.0 (5535) | 4.8 (603) | 4.6 (310) | 7.6 (487) | 15.0 (188 093) | 3.8 (2512) |

| ≥85 | 3.9 (1430) | 1.0 (128) | 1.1 (74) | 2.1 (137) | 6.3 (78 963) | 1.1 (705) |

| Women, % (n) | 70.3 (25 972) | 55.6 (7032) | 32.4 (2206) | 86.2 (5538) | 60.5 (759 935) | 83.2 (55 705) |

| With ≥1 RMD, % (n) | 62.2 (22 962) | 62.3 (7885) | 51.4 (3500) | 53.8 (3457) | 5.3 (66 412) | 56.1 (37 557) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, % (n) | ||||||

| Low score 0 | 41.9 (15 467) | 75.7 (9571) | 79.3 (5398) | 49.4 (3172) | 70.3 (882 856) | 74.1 (49 631) |

| Medium score (1–3) | 56.2 (20 771) | 23.6 (2990) | 20.0 (1364) | 49.0 (3147) | 28.4 (357 227) | 25.4 (16 972) |

| High score (4+) | 1.9 (694) | 0.7 (88) | 0.7 (49) | 1.6 (104) | 1.3 (15 916) | 0.5 (341) |

| History of conditions associated with opioid dependency, % (n) | ||||||

| Alcohol dependency | 0.9 (346) | 1.8 (227) | 1.6 (111) | 1.2 (77) | 1.5 (19 157) | 1.6 (1067) |

| Substance use disorder | 0.4 (162) | 0.7 (88) | 1.0 (69) | 0.6 (40) | 0.7 (9251) | 1.4 (921) |

| Depression | 14.0 (5157) | 17.1 (2159) | 15.1 (1026) | 19.4 (1246) | 15.2 (190 565) | 30.2 (20 204) |

| Suicide and self-harm | 1.3 (464) | 2.0 (256) | 2.0 (139) | 2.7 (172) | 1.8 (22 597) | 4.3 (2878) |

AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis; RMD: rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Trends of new and prevalent opioid users, 2006–2021

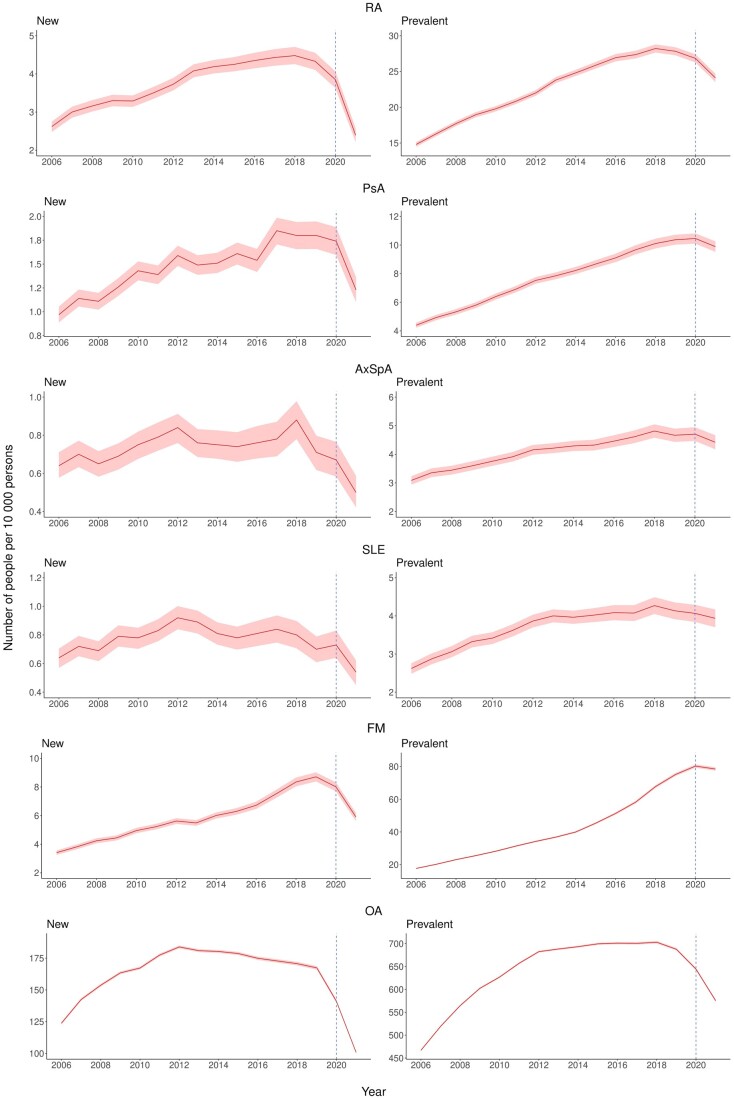

The trends for new opioid users are displayed in Fig. 1, and significant change points are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4, available at Rheumatology online. New opioid users for RA increased from 2.6/10 000 persons in 2006 to 4.5 in 2018. PsA and FM also showed similar trends increasing from 1.0 and 3.4/10 000 persons in 2006 to 1.8 and 8.7/10 000 persons, respectively, in 2019. A decrease was then observed for the remaining study period and in August 2021 the rate for RA, PsA and FM was 2.4, 1.2 and 5.9/10 000 persons, respectively. Regarding SLE and OA, a reduction in the trend of new opioid users was detected in 2013. There was no clear trend observed for AxSpA over the 15 years.

Figure 1.

Trends for age and gender standardized rates of new and prevalent opioid users by RMD, 2006–2021. AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis

The trends and change points for prevalent opioid users are summarized in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S5, available at Rheumatology online. Prevalent opioid users increased from 2006 to 2018 for OA, to 2019 for RA, AxSpA and SLE, and to 2020 for PsA, and plateaued or decreased afterwards. Prevalent opioid users for OA increased from 466.8/10 000 persons in 2006 to a peak of 703.0 in 2018 before decreasing to 575.3 in 2021. FM showed an increasing trend for prevalent opioid users until 2021, with a 4.5-fold increase from 17.7/10 000 persons in 2006 to 78.5 in 2021.

Prescribing patterns in new and prevalent opioid users, 2006–2021

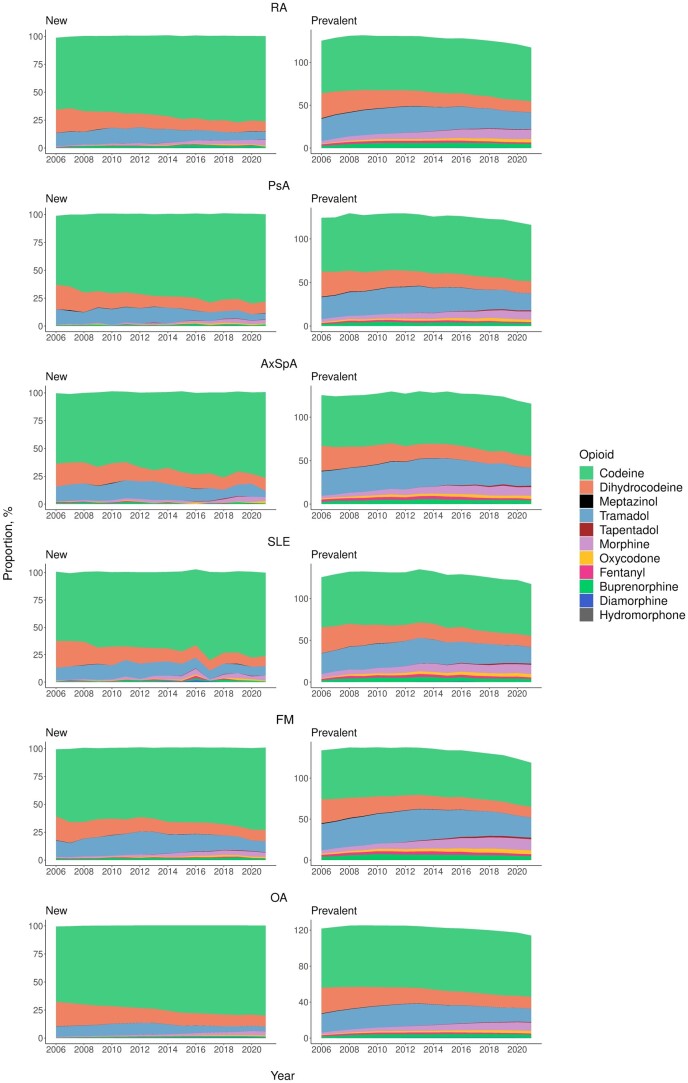

The types of opioids prescribed for new and prevalent opioid users have changed over time (Fig. 2). In new opioid users, the proportion of codeine increased (∼60% vs ≥70% of all opioid use) from 2006 to 2021 across RMDs, whereas a decrease in dihydrocodeine (∼20% vs ∼10%) and tramadol (10–15% vs <10%) was observed. There was a noticeable increase in morphine prescribed for new users: <1% in 2006 vs 3–5% in 2021. Prevalent opioid users demonstrated a similar pattern but showed a clearer increase in strong opioids between 2006 and 2021: 3- to 4-fold increase in morphine (2–4% to 9–13%), 2.5- to 5-fold increase in oxycodone (0.7–1.5% to 2.9–4.7%), and 1.2- to 2-fold increase in buprenorphine (1.7–3.9% to 3.1–4.6%). In contrast, the use of fentanyl showed a consistent proportion (1–2%) in the period. The details of the proportions of each opioid are provided in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, available at Rheumatology online.

Figure 2.

Proportions of opioid drugs prescribed for new and prevalent opioid users by RMD, 2006–2021. The sum of the proportions could be more than 100% because a new user might take more than one type of opioid in the first opioid prescription, and a prevalent user could take more than one type of opioid in the same calendar year. AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis

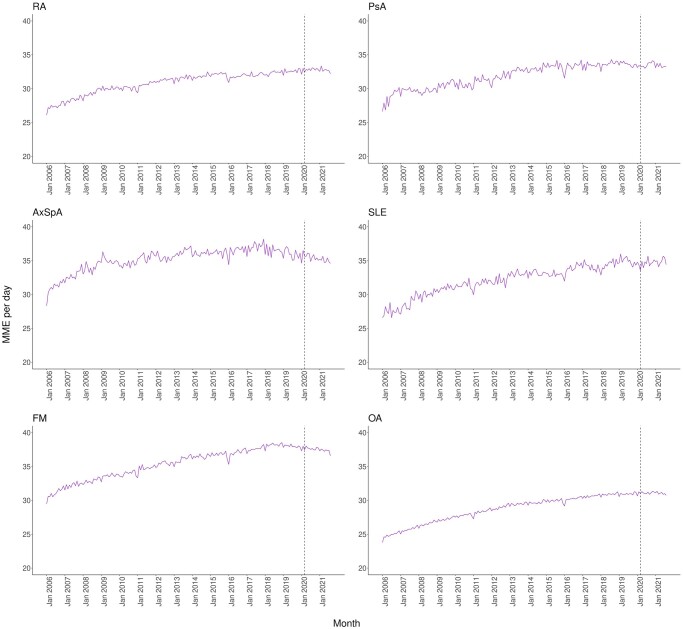

Prescribing patterns in terms of MME/day and the number and duration of opioid prescriptions were further investigated in prevalent opioid users. All RMDs showed increasing trends of MME/day from 2006 to 2021, with 26–27 to 33–35 for inflammatory RMDs and SLE, 23–30 for OA, and 29–37 for FM (Fig. 3). FM had the highest MME/day (≥35), followed by AxSpA and SLE (34–35). However, the total number of opioid prescriptions per month between 2006 and 2021 remained stable, while the total duration of prescriptions per month increased from 2006 to the period 2016–2017 and slightly reduced afterwards (Supplementary Fig. S6, available at Rheumatology online).

Figure 3.

Trends of MME per day among prevalent opioid users by RMD, January 2006 to August 2021. AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid prescribing, 2015–2021

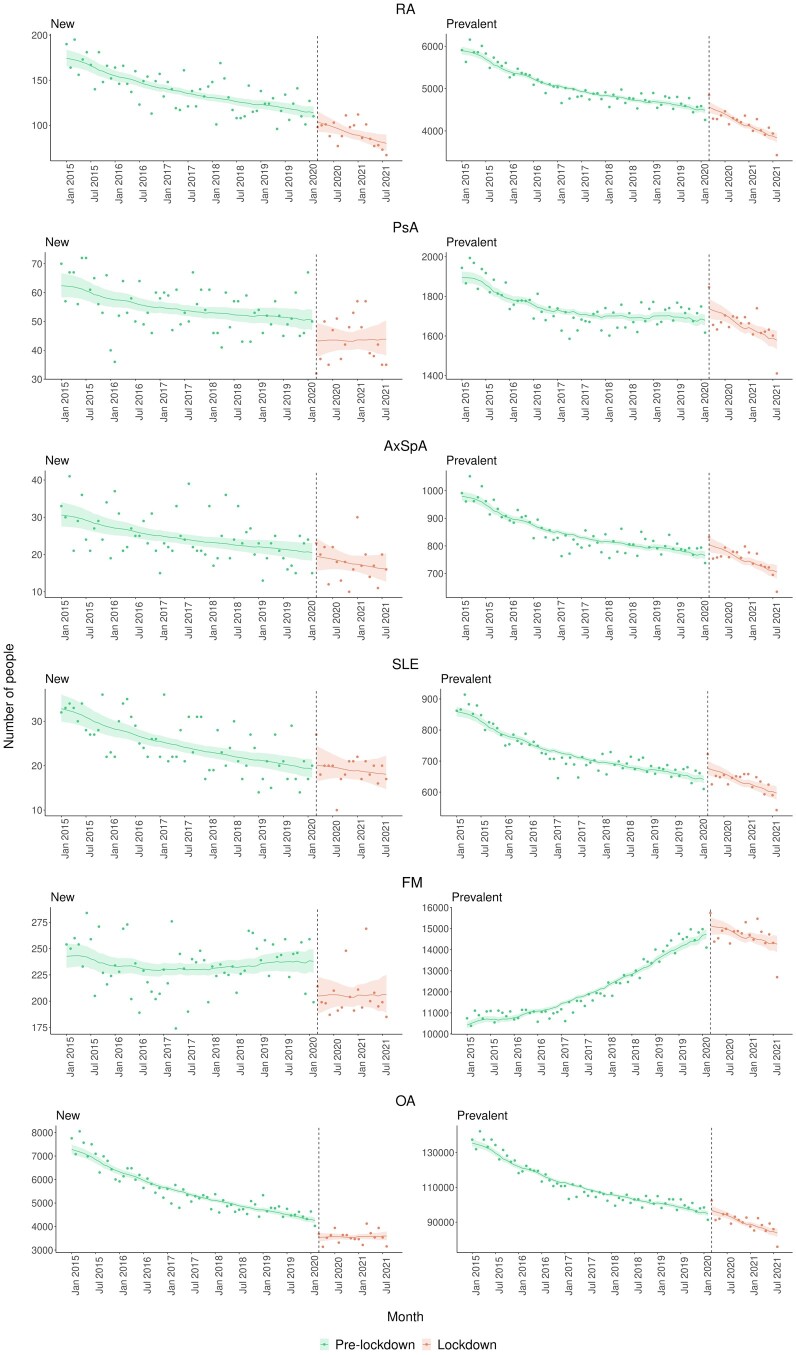

The number of new and prevalent opioid users before and after the pandemic was examined and shown in Fig. 4, with monthly observed values as points and model estimates and 95% CIs as lines. Only OA showed a significant reduction in the average number of new opioid users during the pandemic, but the trend over the pandemic appeared flat. This description was supported by a combined effect of (−0.006; 95% CI: −0.007, −0.005), (−0.808; 95% CI: −1.180, −0.434) and (0.010; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.015) (Supplementary Table S5, available at Rheumatology online). The positive interaction term indicated different trends between the pandemic and pre-pandemic. Others such as PsA and FM experienced a reduction in new users during the pandemic, but the difference was not statistically significant. Regarding prevalent users, RA, PsA and FM showed a significant change in the trend during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic.

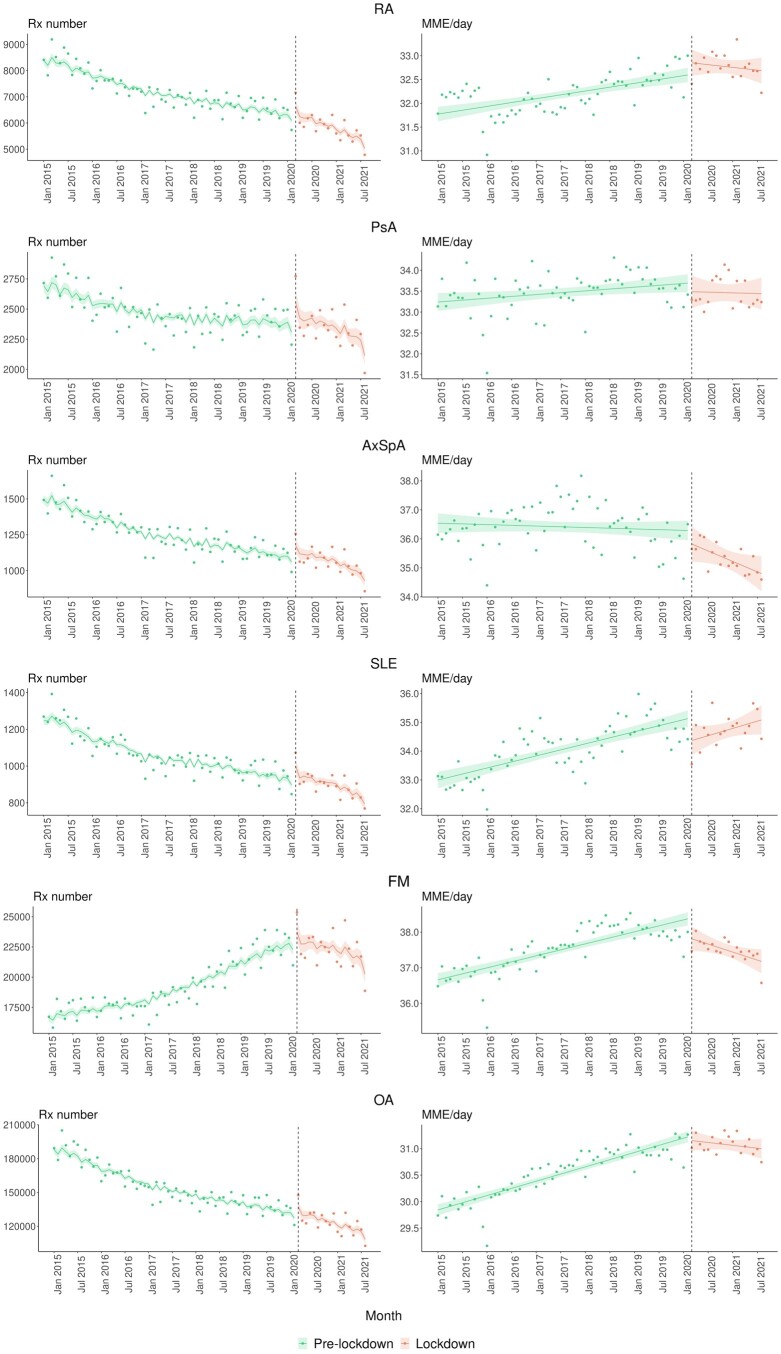

Figure 4.

Temporal variation in the number of opioid users by RMD, January 2015 to August 2021. Observed values are presented as points and model estimates and 95% CIs as lines. AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis

The number of prevalent users with RA decreased by −0.001 (95% CI: −0.002, −0.001) per logarithm of the population registered in CPRD pre-pandemic but declined five times more steeply during the pandemic (−0.005; 95% CI: −0.008, −0.002) (Supplementary Table S5, available at Rheumatology online). PsA had a decreasing-to-flat curve (0.0010; 95% CI: 0.0006, 0.0015) pre-pandemic, which changed by −0.003 (95% CI: −0.006, −0.0003) during the pandemic, resulting in a decreasing trend. FM, conversely, had an increasing trend pre-pandemic (0.009; 95% CI: 0.008, 0.009) and this trend started decreasing by −0.009 (95% CI: −0.011, −0.006) during the pandemic.

Figure 5 demonstrates the number of opioid prescriptions and MME/day among prevalent users before and after the pandemic. During the pandemic, trends of opioid prescriptions for RA and FM changed significantly. RA had more than one times faster decrease in opioid prescriptions (−0.004; 95% CI: −0.008, −0.001) during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (−0.003; 95% CI: −0.003, −0.002) (Supplementary Table S6, available at Rheumatology online). FM had an increasing trend pre-pandemic (0.003; 95% CI: 0.002, 0.003) and this changed by −0.007 (95% CI: −0.010, −0.003) during the pandemic, resulting in a decreasing trend throughout the pandemic. Regarding MME/day, both FM and OA showed increasing trends pre-pandemic, followed by changes of −0.065 (95% CI: −0.100, −0.031) for FM and −0.031 (95% CI: −0.051, −0.012) for OA during the pandemic.

Figure 5.

Temporal variation in the number of opioid prescriptions and MME/day among prevalent opioid users by RMD, January 2015 to August 2021. Observed values are presented as points and model estimates and 95% CIs as lines. AxSpa: axial spondyloarthritis

Discussion

Trends for new and prevalent opioid users have increased overall since 2006, but plateaued or decreased after 2018 for most RMDs, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. The stabilization of trends likely reflects an increasing awareness of and the effort to tackle a surge in opioid prescribing in UK primary care, where national regulations have been set up to improve the use and monitoring of controlled drugs including opioids since 2013 [16]. The reduction in both new and prevalent opioid users from 2018 onwards appears reassuring, but a more frequent intake of potent or high-dosage opioids among RMDs is concerning. A proportional increase in codeine and a decrease in dihydrocodeine and tramadol were observed for both new and prevalent users. Among prevalent users, there was a noticeably proportional increase in strong opioids, such as morphine, oxycodone and buprenorphine, and an increase of ∼7 units in MME/day from 2006 to 2021. FM (≥35) and AxSpA (34–35) had the highest overall MME/day, which is much higher than a previous UK study on new opioid users for non-cancer pain (12 MME/day) [17]. This is possibly attributed to a lack of evidence supporting the use and effectiveness of opioids in FM [18] and AxSpA [19, 20].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer prevalent users in RA, PsA and FM, fewer new users in OA, and decreasing trends of MME/day in FM and OA were observed. The pandemic would prevent patients from receiving treatments due to either having difficulties accessing the healthcare system or being less willing to attend GP practices. GPs might tend to be more cautious about opioid prescribing to accommodate to the pandemic when frequent monitoring might not be feasible. Opioids are also controlled drugs in the UK that require more extensive checks, which may have made remote prescribing of opioids more difficult. It could also suggest that GPs may have changed prescribing patterns of opioid therapy for some RMDs, for example, preferring lower MME/day for non-inflammatory RMDs but keeping similar potency for inflammatory RMDs and SLE.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FM is more marked ranging from the number of prevalent users and opioid prescriptions to MME/day. Recent work reported that RMD patients over the pandemic had experienced poor disease management, elevated pain, anxiety, depression and disruption in access to healthcare services [21, 22], reinforcing the complexity of pain management and concern about opioid prescribing for RMDs in this period [12]. The reason why FM was most affected by the pandemic in terms of a fall in prescribing compared with other RMDs may be related to the limited evidence of opioid efficacy in chronic primary pain conditions. GPs might have been hesitant to prescribe opioids or preferred less potent opioids when FM patients had difficulties accessing non-pharmacological alternatives, or have been made aware of opioids not recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for FM anymore since April 2021 [18]. Some trends appeared to change graphically during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic but were unable to reach statistical significance. This is probably attributable to relatively small sample sizes that lead to large variability of model estimates.

Comparison with existing literature

There is little evidence on the trends of opioid prescribing, stratified by RMDs. A previous UK study did not show an increasing prevalence of opioid prescriptions in patients with inflammatory arthritis (i.e. RA, PsA and AxSpA) between 2000 and 2015 but did show a small increase in strong opioids [6]. The previous work was a regional study in North Staffordshire and might not be representative of the national population. An American study reported a similar trend of regular opioid users with RA, increasing from 2006 to 2010 and then declining slightly until 2014 [7], compared with 2018 in our study. OA had a steady increase in analgesic prescriptions between 2012 and 2017 in the USA [23] but showed stable rates of opioid prescriptions between 2008 and 2017 in the Netherlands [8]. Our findings suggest OA had different trends in the UK, where new and prevalent opioid users increased from 2006, but new users dropped after 2013, and prevalent users dropped after 2018.

A recent US study found opioid prescriptions for opioid-naïve patients and their total MMEs decreased temporarily and then rebounded during the COVID-19 pandemic, while existing opioid users maintained access to these medications [24]. Our study, however, demonstrates different findings that only OA showed a significant reduction in new opioid users persistently over the pandemic, while fewer prevalent opioid users were observed in RA, PsA and FM. Both FM and OA showed decreasing trends of MME/day during the pandemic despite the increasing trends pre-pandemic, whereas other RMDs did not.

Our findings of increases in strong opioids (e.g. oxycodone) are supported by previous work on inflammatory arthritis [6] and OA [8]. However, we found a stable trend of fentanyl and an increase in codeine in RMDs while the use of fentanyl increased and paracetamol/codeine decreased for OA in the Netherlands between 2008 and 2017 [8]. Our previous work on non-cancer pain using CPRD with an overlapping period of 2006–2017 [3] showed a steady increase in codeine and a plateau in dihydrocodeine and tramadol after 2012, supporting the reduction in dihydrocodeine and tramadol for RMDs in this study.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, the RA cohort was identified using a validated algorithm [25] and the Read Code lists of other RMDs were confirmed by health professionals. Second, this study, to our knowledge, is the first study to analyse opioid prescribing trends in various ways including MME/day for individual RMD. Lastly, the study period across pre- and post-pandemic time windows is useful to examine the opioid trends in the recent decades and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some limitations of this study include that the number of patients with a specific RMD registered in CPRD cannot be obtained, given the fact that researchers are not allowed to download the entire CPRD cohort and identify those with RMDs. Trends of new and prevalent opioid users are not comparable between RMDs because they are subject to the underlying prevalence of disease in the population. However, the prevalence of disease was assumed not to change drastically in the study period supported by the literature [26–30]. Also, information on opioids prescribed in the hospital or obtained over-the-counter was not available in this study as the focus was on primary care prescriptions. Furthermore, the CPRD database has different registration rates of practices across regions, for example, a high registration rate in the North West (11.8%) but a low rate in the North East (1.5%) [13]. This varied uptake may affect regional representativeness across the UK.

Implications for clinical practice

Despite the reassuring results of plateauing/decreasing trends for opioid users, our findings flag a warning that opioid prescribing in FM and AxSpA may need to be monitored closely in the clinical setting. In light of the limited evidence on opioid therapy for the two RMDs, clinicians should proactively consider incorporating non-opioid medicines and/or non-pharmacological treatments to help manage chronic pain rather than relying on increasing the dose and/or potency of opioid therapy.

This study also indicates the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic appeared persistent and did not rebound to normal after the gradual lifting of the lockdown (i.e. March 2021 onwards). This may reflect the fact that GPs in the UK have been struggling to go back to the same service level as the pre-pandemic time. The consistent drop in opioid prescribing among RMDs may be a combined effect of a reduction in opioid therapy that RMD patients received and reduced healthcare services. This phenomenon is concerning as it may delay prompt interventions for RMD patients.

Conclusion

The plateauing/decreasing trend of opioid users in RMDs after 2018 may reflect the efforts made to tackle the rising prescribing of opioids in UK primary care. Despite this reassurance, the increase in strong opioids and MME/day suggests challenges in pain management for some RMDs. FM, with the highest overall MME/day, showed different trends compared with other RMDs in terms of the increase in prevalent opioid users till 2021 and opposite trends for opioid prescribing during the pandemic. The pandemic led to fewer people on opioids for most RMDs, which is reassuring as there was no sudden increase in opioid prescribing during the pandemic in the UK.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ruth Costello and Ramiro Bravo for data management.

Contributor Information

Yun-Ting Huang, Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

David A Jenkins, Centre for Health Informatics, Division of Informatics, Imaging and Data Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Belay Birlie Yimer, Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Jose Benitez-Aurioles, Centre for Health Informatics, Division of Informatics, Imaging and Data Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Niels Peek, Centre for Health Informatics, Division of Informatics, Imaging and Data Science, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, UK.

Mark Lunt, Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

William G Dixon, Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, UK; Department of Rheumatology, Salford Royal Hospital, Northern Care Alliance, Salford, UK.

Meghna Jani, Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, Centre for Musculoskeletal Research, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, UK; Department of Rheumatology, Salford Royal Hospital, Northern Care Alliance, Salford, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

This study used pseudonymized patient-level data from the CPRD. The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to CPRD regulations and ethical reasons. Other researchers can use patient-level CPRD data in a secure environment by applying to the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee. Details of the application process and conditions of access are provided by the CPRD at https://www.cprd.com/Data-access.

Contribution statement

M.J. conceived the study and is the Principal Investigator on the project. M.J. along with W.G.D., N.P., M.L., D.A.J. and B.B.Y. secured funding and help supervise the conduct of the study. Y.T.H. led the data preparation and analysis supported by D.A.J., B.B.Y. and M.L. who had access to the data. Y.T.H. drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings, critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to revisions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a FOREUM grant (grant ID: 125059) and NIHR grant (NIHR301413). M.J. is funded through an NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR301413). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. J.B.A. is the receipt of studentship awards from the Health Data Research UK-The Alan Turing Institute Wellcome PhD Programme in Health Data Science (Grant Ref: 218529/Z/19/Z).

Disclosure statement: W.G.D. has received consultancy fees from Google unrelated to this work. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the CPRD’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (approval number: 20_000143).

References

- 1. Belzak L, Halverson J.. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2018;38:224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Lancet Public Health. Opioid overdose crisis: time for a radical rethink. Lancet Public Health 2022;7:e195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jani M, Birlie Yimer B, Sheppard T, Lunt M, Dixon WG.. Time trends and prescribing patterns of opioid drugs in UK primary care patients with non-cancer pain: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curtis HJ, Croker R, Walker AJ. et al. Opioid prescribing trends and geographical variation in England, 1998–2018: a retrospective database study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R. et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott IC, Bailey J, White CR, Mallen CD, Muller S.. Analgesic prescribing in patients with inflammatory arthritis in England: an observational study using electronic healthcare record data. Rheumatology 2022;61:3201–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Curtis JR, Xie F, Smith C. et al. Changing trends in opioid use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van den Driest JJ, Schiphof D, de Wilde M. et al. Opioid prescriptions in patients with osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology 2020;59:2462–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute for Government. Timeline of UK government coronavirus lockdowns and restrictions. London: Institute for Government, 2022. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns (9 March 2022 , date last accessed).

- 10. Williams R, Jenkins DA, Ashcroft DM. et al. Diagnosis of physical and mental health conditions in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Lancet. A time of crisis for the opioid epidemic in the USA. Lancet 2021;398:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Lancet Rheumatology. Opioid use in rheumatic diseases: preventing another pandemic. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K. et al. Data Resource Profile: clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiology 2015;44:827–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pye SR, Sheppard T, Joseph RM. et al. Assumptions made when preparing drug exposure data for analysis have an impact on results: an unreported step in pharmacoepidemiology studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 2018;27:781–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A.. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Department of Health. Controlled Drugs (Supervision of management and use) Regulations 2013: Information about the Regulations. London: Department of Health, 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214915/15-02-2013-controlled-drugs-regulation-information.pdf (23 May 2022, date last accessed).

- 17. Jani M, Girard N, Bates DW. et al. Opioid prescribing among new users for non-cancer pain in the USA, Canada, UK, and Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain. London: NICE, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (13 June 2022, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 19. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R. et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Anna Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS. et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association Of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aloush V, Gurfinkel A, Shachar N, Ablin JN, Elkana O.. Physical and mental impact of COVID-19 outbreak on fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2021;39(Suppl 130):108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garrido-Cumbrera M, Marzo-Ortega H, Christen L. et al. Assessment of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in Europe: results from the REUMAVID study (phase 1). RMD Open 2021;7:e001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trentalange M, Runels T, Bean A. et al. ; EAASE (Evaluating Arthritis Analgesic Safety and Effectiveness) Investigators. Analgesic prescribing trends in a national sample of older veterans with osteoarthritis: 2012-2017. Pain 2019;160:1319–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Currie JM, Schnell MK, Schwandt H, Zhang J.. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e216147-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas SL, Edwards CJ, Smeeth L, Cooper C, Hall AJ.. How accurate are diagnoses for rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the general practice research database? Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abhishek A, Doherty M, Kuo C-F. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is getting less frequent—results of a nationwide population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:736–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ogdie A, Langan S, Love T. et al. Prevalence and treatment patterns of psoriatic arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:568–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, Lanyon P, Zhang W.. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology 2017;56:1945–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crossfield SSR, Marzo-Ortega H, Kingsbury SR, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Conaghan PG.. Changes in ankylosing spondylitis incidence, prevalence and time to diagnosis over two decades. RMD Open 2021;7:e001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Swain S, Sarmanova A, Mallen C. et al. Trends in incidence and prevalence of osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom: findings from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020;28:792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study used pseudonymized patient-level data from the CPRD. The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to CPRD regulations and ethical reasons. Other researchers can use patient-level CPRD data in a secure environment by applying to the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee. Details of the application process and conditions of access are provided by the CPRD at https://www.cprd.com/Data-access.