Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Prone positioning for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) has historically been underused, but was widely adopted for COVID-19-associated ARDS early in the pandemic. Whether this successful implementation has been sustained over the first 3 years of the COVID-19 pandemic is unknown. In this study, we characterized proning use in patients with COVID-19 ARDS from March 2020 to December 2022.

DESIGN:

Multicenter retrospective observational study.

SETTING:

Five-hospital health system in Maryland, USA.

PATIENTS:

Adults with COVID-19 supported with invasive mechanical ventilation and with a Pao2/Fio2 ratio of less than or equal to 150 mm Hg while receiving Fio2 of greater than or equal to 0.6 within 72 hours of intubation.

INTERVENTIONS:

None.

MEASUREMENTS:

We extracted demographic, clinical, and positioning data from the electronic medical record. The primary outcome was the initiation of proning within 48 hours of meeting criteria. We compared proning use by year with univariate and multivariate relative risk (RR) regression. Additionally, we evaluated the association of treatment during a COVID-19 surge period and receipt of prone positioning.

MAIN RESULTS:

We identified 656 qualifying patients; 341 from 2020, 224 from 2021, and 91 from 2022. More than half (53%) met severe ARDS criteria. Early proning occurred in 56.2% of patients in 2020, 56.7% in 2021, and 27.5% in 2022. This translated to a 51% reduction in use of prone positioning among patients treated in 2022 versus 2020 (RR = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.33–0.72; p < 0.001). This reduction remained significant in adjusted models (adjusted RR = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.42–0.82; p = 0.002). Treatment during COVID-19 surge periods was associated with a 7% increase in proning use (adjusted RR = 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.13; p = 0.01).

CONCLUSIONS:

The use of prone positioning for COVID-19 ARDS is declining. Interventions to increase and sustain appropriate use of this evidence-based therapy are warranted.

Keywords: adult respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, implementation science, intensive care units, prone position

BRIEF REPORT

Prone positioning is a key evidence-based therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1). During the COVID-19 pandemic proning of patients with COVID-19-associated ARDS was widely adopted (2, 3). Although this represents the successful implementation of a historically underused therapy (4, 5), prior studies on implementation of evidence-based ICU care suggest that without specific support, use of appropriate therapies can decline (6). Whether the higher use of prone positioning seen early in the pandemic has been sustained over time is unknown. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective observational study to examine trends in proning use in COVID-19 ARDS from March 2020 to December 2022.

Methods

Data were acquired from the electronic medical records (EMR) of five Johns Hopkins Health System (JHHS) hospitals in the Baltimore-Washington, DC, region. Adult patients (≥ 18 yr of age) were included if they (1), had confirmed or suspected COVID-19 (2), were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), and (3) met criteria for proning within the first 72 hours of mechanical ventilation (MV) initiation (Pao2/Fio2 ≤ 150 mm Hg on Fio2 ≥ 0.6). We excluded patients who were initiated on IMV at hospitals outside of the JHHS.

The primary outcome was initiation of early prolonged prone positioning (≥ 12 continuous hr in the prone position started within 48 hr of initiating IMV). Demographic, clinical, and positioning variables were extracted from EMR data as described previously (3). We compared proning rates for patients treated in 2020, 2021, and 2022 using unadjusted and multivariable Poisson regression based on generalized estimating equations to account for potential correlation within each hospital and used robust standard errors (relative risk [RR] regression) (7). In a secondary analysis, we evaluated the association of patient treatment during a COVID-19 surge period and receipt of early proning. COVID-19 surge periods were defined as months that had greater than or equal to the upper quartile of eligible patients treated per month in the data. Adjusted models included prespecified covariates thought to influence use of proning (age > 80 yr, body mass index [BMI], <30, 30–49, 50+ [kg/m2], Charlson comorbidity score, ARDS severity using Pao2/Fio2 as a continuous variable, and positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] at time of proning eligibility). Study year was also included in the multivariable model evaluating the association between COVID-19 surges and proning use. Model results are presented as RRs with corresponding 95% CIs. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board acknowledged this work as secondary research exempt from further human subjects review (IRB00280745).

Results

Of 656 qualifying patients, 341 (52.4%), 224 (34.4%), and 91 (13.9%) were admitted in 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively (Table 1). The median age was 63 years (interquartile range [IQR] 53–72), 53% met severe ARDS criteria (Pao2/Fio2 < 100 mm Hg), and the median Charlson comorbidity score was 0 (IQR 0–2). Patients treated in 2020 and 2021 had higher BMI, nonrespiratory sequential organ failure scores, PEEP, plateau pressure, and use of neuromuscular blockade infusion compared with those treated in 2022. The percentage of patients treated at one of the two academic hospitals in the health system declined over time (2020: 71%, 2021: 61%, 2022: 54%; p = 0.004). Overall, in-hospital mortality was lowest in 2020 (2020: 38%, 2021: 54%, 2022: 51%; p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and Proning Outcomes for COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Patients by Year

| Characteristics and Outcomes | 2020 (n = 341) | 2021 (n = 224) | 2022 (n = 91) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (yr) | 63 (54–72) | 61 (50–72) | 67 (54–76) | 0.09 |

| Female | 141 (41%) | 89 (40%) | 42 (46%) | 0.58 |

| Non-White racea | 245 (72%) | 115 (52%) | 44 (49%) | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Clinical/treatment characteristics | ||||

| Treated at Academic Hospital | 241 (71%) | 137 (61%) | 49 (54%) | 0.004 |

| Treated during COVID-19 surgeb | 249 (73%) | 134 (60%) | 56 (62%) | 0.002 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 31 (27–37) | 31 (26–37) | 28 (24–33) | < 0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.41 |

| Nonrespiratory Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scorea,c | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (6–10) | 0.04 |

| Vasopressor infusion, first 48 hrd | 296 (87%) | 190 (85%) | 70 (77%) | 0.08 |

| Neuromuscular blocker infusion, first 48 hrd | 142 (42%) | 106 (47%) | 27 (30%) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Respiratory variables at eligibility | ||||

| Pao2/Fio2 (mm Hg) | 99 (77–122) | 96 (74–118) | 97 (70–117) | 0.29 |

| Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (P/F ≤ 100 mm Hg) | 175 (51%) | 122 (54%) | 49 (54%) | 0.75 |

| Fio2 (mm Hg) | 1.0 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.0) | 0.30 |

| PaCo2 (mm Hg) | 45 (38–51) | 45 (40–52) | 44 (38–55) | 0.65 |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure (cm H2o)a | 10 (10–14) | 10 (10–14) | 10 (6–12) | < 0.001 |

| Tidal volume (mL/kg of ideal body weight)a | 6 (6–7) | 6 (6–7) | 6 (6–7) | 0.56 |

| Plateau pressure (cm H2o)a,e | 25 (22–28) | 25 (20–29) | 24 (20–27) | 0.04 |

|

| ||||

| Patient outcomes | ||||

| Hospital length of stay (d) | 25 (15–40) | 24 (15–36) | 20 (11–28) | 0.005 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (d) | 13 (8–25) | 13 (6–23) | 7 (4–16) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 129 (38%) | 120 (54%) | 46 (51%) | < 0.001 |

| Discharged home | 94 (28%) | 43 (19%) | 19 (21%) | 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| Proning outcomef | ||||

| Prone within 48 hr of criteria, n (%) (95% CI) | 192 (56.3%) (50.6–62.0) | 127 (56.7%) (51.4–62.0) | 25 (27.5%) (17.2–37.8) | < 0.001 |

Missing data (% missing, n missing): race (0.6%, n = 4), body mass index (2.4%, n = 16), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (0.3%, n = 2), positive end-expiratory pressure (1.8%, n = 12), tidal volume (2.3%, n = 15), and plateau pressure (2.7%, n = 18).

COVID-19 surge periods are defined as study months in the upper quartile of eligible patients /mo.

Calculated as sum of highest subscores in the 24-hr period before or after eligibility.

Infusion during proning eligibility period.

Plateau pressure extracted as the recorded value closest to eligibility. For airway pressure release ventilation, pressure high is used as plateau pressure.

Early prolonged proning (≥ 12 continuous hours in prone position initiated within 48 hr if criteria).

Data are presented as median (interquartile region) or n (%).

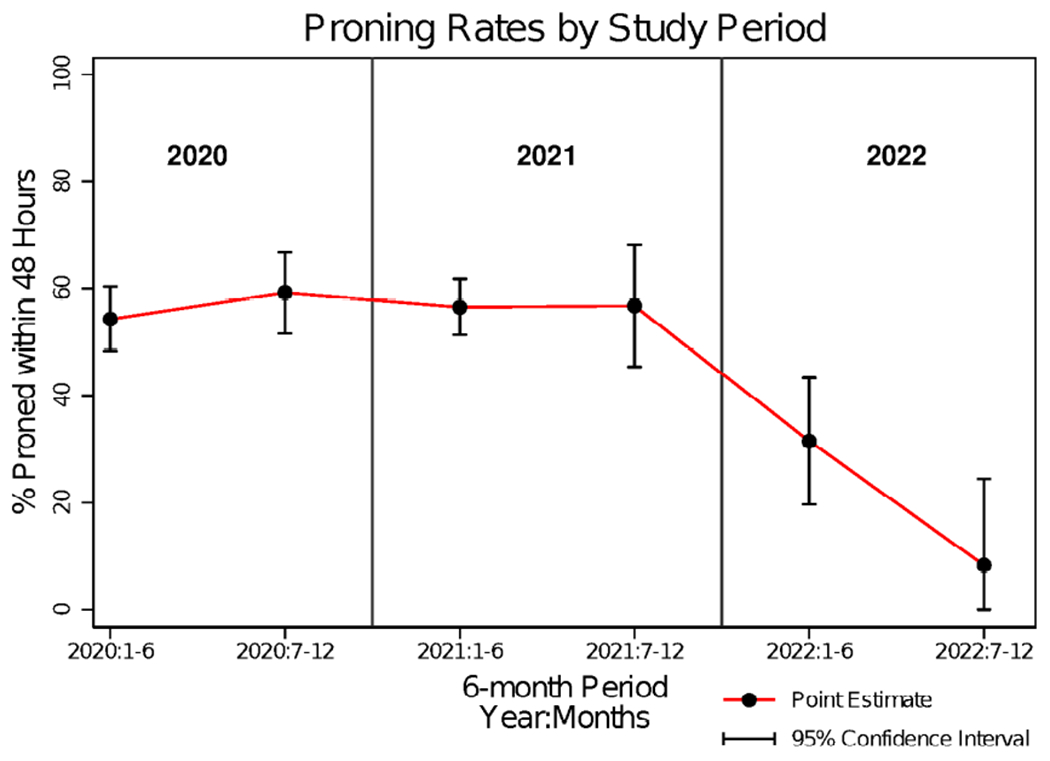

The percentage of patients who received early proning was 56.3% in 2020, 56.7% in 2021 and 27.5% in 2022 (Table 1; Fig. 1). Compared with 2020, proning in 2022 declined by 51% (RR = 0.49; 95% CI, 0.33–0.72, p < 0.001) and this reduction persisted after adjustment for patient characteristics (adjusted RR [aRR] = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.42–0.82; p = 0.002). In contrast, proning rates in 2020 and 2021 did not differ based on unadjusted and adjusted model results (adjusted RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83–1.17; p = 0.87). Proning frequencies for academic versus community hospitals were similar (54.3% and 48.9% in the cohort overall; p = 0.19). Lastly, treatment during a COVID-19 surge was associated with receipt of early proning (aRR = 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.13; p = 0.01). Missing data were minimal and complete-case analysis was used in adjusted models (Table 1 footnote).

Figure 1.

Initiation of early prone positioning in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome over time. The frequency of early prone positioning is shown in 6-mo intervals from 2020 to 2022. Early prone positioning is defined as initiating prolonged proning sessions (at least 12 hr in prone position) within 48 hr of meeting proning criteria.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of adult patients meeting oxygenation criteria for proning in the setting of moderate-severe COVID-19 ARDS, we observed a 51% relative decline in the initiation of early prone positioning in 2022 compared with 2020 even after adjusting for patient features associated with proning. In multivariable models, hospital admission during a COVID-19 surge period was associated with increased use of proning.

To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating a decline in proning use after the initial widespread uptake seen early in the COVID-19 pandemic (2, 3). This is notable, as the initial widespread adoption of proning was considered an implementation success. For example, in our own health system, proning was historically used in just 9% of qualifying ARDS patients (2018–2019) versus 60% of those with COVID-19 ARDS treated in the first year of the pandemic (3). This shows that barriers to proning, including clinicians recognition of ARDS, viewing proning as a labor-intensive and/or salvage therapy, and a preference for other adjunctive ARDS therapies (4, 8), were partially overcome early in the pandemic (9). However, the declining use of proning shown in this study; however, suggests ongoing and new impediments to proning use. This decline may be due in part to loss of specific resources that facilitated the initial expansion of proning early in the pandemic, such as dedicated proning teams and readily available proning educational materials (9). Additionally, ICU staff expertise and leadership from experienced nurses, key facilitators of proning (9), may have decreased due to high ICU staff turnover that followed the early surges of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021.

In our data, patient features do not explain the decline in proning use over time. Despite this, it may be that patients who developed COVID-19 ARDS in 2022 differed from those treated earlier in the pandemic in ways that are not captured in these data. Declining proning use may also relate to clinician and process factors. For example, treatment during COVID-19 surge periods was associated with an increased likelihood of proning. This may indicate the presence of recency bias, in which immediate past experience with similar patients leads to improved improving recognition and initiation of appropriate ARDS care. This could be in addition to an effect of patient cohorts on workflows that supported prone positioning. As the pandemic wanes with fewer cases of COVID-19 ARDS, these mechanisms could explain declines in proning use.

Given the known mortality benefit of prone positioning in ARDS, a decline in the appropriate use of prone positioning is anticipated to result in worse outcomes for qualifying patients. This is particularly notable as these data and others, show increased mortality in critically ill COVID-19 cohorts over time (10). Although we cannot attribute this mortality trend solely to declining use of prone positioning use or other care differences, evidence-based best practices should always be pursued, as should the institutional supports that enable them.

The erosion of proning use that we have observed for COVID-19 ARDS demonstrates an important implementation and sustainment challenge for the use of prone positioning in ARDS. Although our data generate several hypotheses regarding why practice changes have occurred, further study is needed to understand and address the mechanisms that drive wanted and unwanted practice changes. Research strategies should include quantitative, qualitative, and ethnographic approaches to generate a more comprehensive understanding of the implementation phenomenon we have observed and to inform effective implementation and sustainment strategies to facilitate the use of proning.

Our findings are limited to a COVID-19 ARDS cohort from a five-hospital health system. However, the system is diverse in its composition with representation from both academic and community hospitals, each with its own providers, nurses, respiratory therapists, and other staff. Our results may therefore be reflective of trends in COVID-19 ARDS management more broadly. A second limitation is that ARDS criteria for our 2021 and 2022 cohorts were not manually confirmed by clinician chart review. However, we used the same electronic query methodology as in our prior work where chart review did confirm 95% of cases met the definition of moderate to severe ARDS per the Berlin criteria (3).

In conclusion, use of prone positioning may be declining after the initial marked uptake for COVID-19 ARDS early in the pandemic. Future implementation interventions to improve proning use should include a focus on the sustainability of prone positioning in the ICU.

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Has the use of prone positioning been sustained in ICU practice for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19?

Findings:

There has been a 51% relative decline in the use of prone positioning for patients with COVID-19 adult respiratory distress syndrome from 2020 to 2022, and this decline is not explained by measured patient features.

Meaning:

Through prone positioning was widely adopted at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, specific interventions to sustain appropriate use of this evidence-based therapy are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The data source for this publication is the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Precision Medicine Analytics Platform Registry (JH-CROWN). We thank the many patients, clinicians, and data scientists who made this resource possible.

Biographies

Drs. Hochberg, Eakin, and Hager were involved in conception and design. Drs. Hochberg and Hager were involved in the acquisition of data. Drs. Hochberg, Psoter, Eakin, and Hager were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. Dr. Hochberg was involved in drafting or revising the article. Drs. Hochberg, Psoter, Eakin, and Hager were involved in the final approval of article.

Dr. Hochberg’s institution received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (F32HL160039, T32HL007534). Drs. Hochberg and Eakin received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Eakin’s institution received funding from the NHBLI. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J-C, et al. ; PROSEVA Study Group: Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2159–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. ; STOP-COVID Investigators: Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1436–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochberg CH, Psoter KJ, Sahetya SK, et al. : Comparing prone positioning use in COVID-19 versus historic acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Explor 2022; 4:e0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guérin C, Beuret P, Constantin JM, et al. ; investigators of the APRONET Study Group, the REVA Network, the Réseau recherche de la Société Française d’Anesthésie-Réanimation (SFAR-recherche) and the ESICM Trials Group: A prospective international observational prevalence study on prone positioning of ARDS patients: the APRONET (ARDS Prone Position Network) study. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:22–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qadir N, Bartz RR, Cooter ML, et al. ; Severe ARDS: Generating Evidence (SAGE) Study Investigators: Variation in early management practices in moderate-to-severe ARDS in the United States. Chest 2021; 160:1304–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eakin MN, Ugbah L, Arnautovic T, et al. : Implementing and sustaining an early rehabilitation program in a medical intensive care unit: A qualitative analysis. J Crit Care 2015; 30:698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Qian L, Shi J, et al. : Comparing performance between log-binomial and robust Poisson regression models for estimating risk ratios under model misspecification. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klaiman T, Silvestri JA, Srinivasan T, et al. : Improving prone positioning for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. An implementation-mapping approach. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18:300–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochberg CH, Card ME, Seth B, et al. : factors influencing the implementation of prone positioning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2023; 20:83–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auld SC, Harrington KRV, Adelman MW, et al. ; Emory COVID-19 Quality and Clinical Research Collaborative: Trends in ICU mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: A tale of three surges. Crit Care Med 2022; 50:245–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]