Abstract

Introduction

Exposure to marketing for foods high in sugar, salt, and fat is considered a key risk factor for childhood obesity. To support efforts to limit such marketing, the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe has developed a nutrient profile model (WHO NPM). Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture plans to use this model in proposed new food marketing legislation, but it has not yet been tested in Germany. The present study therefore assesses the feasibility and implications of implementing the WHO NPM in Germany.

Methods

We applied the WHO NPM to a random sample of 660 food and beverage products across 22 product categories on the German market drawn from Open Food Facts, a publicly available product database. We calculated the share of products permitted for marketing to children based on the WHO NPM, both under current market conditions and for several hypothetical reformulation scenarios. We also assessed effects of adaptations to and practical challenges in applying the WHO NPM.

Results

The median share of products permitted for marketing to children across the model’s 22 product categories was 20% (interquartile range (IQR) 3–59%) and increased to 38% (IQR 11–73%) with model adaptations for fruit juice and milk proposed by the German government. With targeted reformulation (assuming a 30% reduction in fat, sugar, sodium, and/or energy), the share of products permitted for marketing to children increased substantially (defined as a relative increase by at least 50%) in several product categories (including bread, processed meat, yogurt and cream, ready-made and convenience foods, and savoury plant-based foods) but changed less in the remaining categories. Practical challenges included the ascertainment of the trans-fatty acid content of products, among others.

Conclusion

The application of the WHO NPM in Germany was found to be feasible. Its use in the proposed legislation on food marketing in Germany seems likely to serve its intended public health objective of limiting marketing in a targeted manner specifically for less healthy products. It seems plausible that it may incentivise reformulation in some product categories. Practical challenges could be addressed with appropriate adaptations and procedural provisions.

Keywords: Food marketing, Nutrient profile model, Marketing regulation, Childhood obesity, Public health nutrition

Plain Language Summary

On TV, on the internet, and in other media, many advertisements for unhealthy foods can be seen. Children who see a lot of these advertisements often eat more unhealthy foods. They also more often have overweight or obesity than other children. The World Health Organization (WHO) therefore recommends that governments should protect children from such advertisements. They have developed a model to tell healthy and unhealthy foods apart. This model can be used in laws that protect children from advertisements for unhealthy foods. The German government wants to introduce such a law. They want to use the WHO model, but with a few changes to make it less strict. According to the proposed new law, only healthy foods could be advertised to children. We wanted to find out how many foods and drinks in Germany are healthy according to the WHO model, both with the changes Germany wants and without any changes to the model. We looked at 22 different groups of foods and drinks, such as sweets, breakfast cereals, milk, fruit juice, bread, and meat. For each group of food and drink, we looked at 30 products that are sold in Germany. We found that on average, one in five products overall (20% of all products) counted as healthy according to the original model. According to the adapted model the German government wants to use, about two in five products (40%) count as healthy. If the food industry reduced the amount of sugar, salt, and fat in products, more would count as healthy. We also found that both versions of the model work quite well in Germany. We therefore think that it is likely that the model proposed by the German government would help protect children from advertisements for unhealthy foods.

Introduction

There is strong direct and indirect evidence that exposure to marketing for ultra-processed foods high in sugar, salt, and/or fat increases the risk for excess energy intake, unhealthy dietary behaviours, and overweight and obesity among children [1–5]. In many countries, children have been shown to be exposed to extensive marketing for such products [6]. This includes Germany, where children aged 3–13 years consuming media are on average exposed to 15 advertisements for unhealthy foods and beverages per day, including 10 on TV and 5 on the internet [7]. On average, 92% of all food and beverage advertisements to which children are exposed to in Germany are for unhealthy products [7]. This is reflected in the sums spent on food advertisements for different product categories in Germany, which amounted to EUR 1.06 billion in 2021 for confectionery, compared to EUR 17.2 million in 2017 for fruit and vegetables (latest available figures, respectively) [8, 9]. Marketing for unhealthy foods and beverages is therefore considered to be an important contributor to the epidemic of obesity and chronic diet-related diseases in Germany and internationally [3, 10].

In light of this evidence, Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture published in February 2023 plans for new legislation on food marketing to which children are exposed [11]. The proposed legislation would limit such marketing to products meeting certain nutrient and ingredient criteria. The law would cover all relevant marketing channels and would use a combination of criteria to define marketing to which children are exposed (a more detailed description of the proposed law is provided in the online supplementary material; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000534542) [11]. If enacted, the law would be among the most comprehensive regulations of food marketing to children worldwide. As of March 2023, 13 countries worldwide have mandatory policies regarding unhealthy food and beverage marketing to children [12]. Of these 13 countries, only two, Portugal and Chile, have comprehensive restrictions on both broadcast and non-broadcast media and limits on persuasive techniques [12].

The proposed new legislation has been welcomed by medical and health organizations [13, 14] but criticised by food industry groups [15]. Among the more contentious aspects of the proposed legislation is its use of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe’s Nutrient Profile Model (WHO NPM) for determining which products may be marketed to children [16]. By some, the WHO NPM has been criticised for being too far-reaching and impractical and for amounting to a total ban of advertisement for a broad range of product categories [15, 17, 18]. Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, by contrast, has emphasized that marketing would still be allowed for products qualifying as healthy, and that it expects industry to reformulate products currently not meeting the relevant nutrient and ingredient criteria [11, 19]. It has also proposed a number of adaptations to the WHO NPM [20].

As part of its development process, the WHO NPM was pilot-tested in 13 European countries, but not in Germany [16]. Similarly, the adaptations to the WHO NPM proposed as part of the planned legislation have not yet been systematically examined. Against this backdrop, the present paper aims to assess the feasibility and implications of implementing the WHO NPM in Germany. Specifically, we apply the WHO NPM (in its original version as well as with the adaptations proposed by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture) to a random sample of products on the German market to assess the share of products that would be marketable under the proposed law, the effects of various hypothetical reformulation scenarios on the share of marketable products, and any practical challenges in applying the WHO NPM in Germany.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional analysis of 660 food and beverage products on the German market randomly sampled from the Open Food Facts product database [21]. Our analysis is based on an a priori protocol registered and published with the Open Science Framework [22] and follows the STROBE and STROBE-nut reporting guidelines [23, 24]. In the following sections, we provide a summary of our methodology. Further details are provided in the online supplementary material.

Data Sources and Methods of Assessment

We used product data provided by Open Food Facts, an online open-source packaged food and beverage database covering more than 2.8 million products globally, of which slightly more than 200,000 are classified as available in Germany [21]. We downloaded the complete database, filtered for products classified as available on the German market, and used R, an open-source statistical analysis software, to extract a randomly ordered list of products. We then used the instructions provided by the WHO NPM manual to successively assign these products to the 22 product categories of the WHO NPM until we identified 30 products for each category, or 660 in total [16]. For six product categories that are rare and were therefore not sufficiently represented in the overall sample, we further filtered the data set for relevant keywords. For the 660 included products, we manually extracted nutrient and ingredient information from the Open Food Facts database. The assignment of products to product categories was done by one author (N.H., A.L., C.K., and E.O.) and double-checked by a second (C.K. and P.v.P.). Inconsistencies and challenges were discussed in the team of all authors. Data extraction was done by one author (N.H., A.L., C.K., and E.O.). For a randomly selected sub-sample of all included products, a second author (C.K.) applied two quality assurance procedures: (a) a check if data had been correctly entered from the Open Food Facts database (for 6% of all sampled products) and (b) a check if the data provided by the Open Food Facts database matched nutrient and ingredient data provided on the websites of manufacturers or (if no manufacturer website could be identified) on the websites of online retailers (for 10% of all sampled products). Overall, we found the data provided by Open Food Facts to be reasonably reliable (see online supplementary material for further details).

Main Variables

We calculated the following variables for each of the 22 product categories defined by the WHO NPM:

-

1.

The share of products not exceeding any nutrient or ingredient threshold (i.e., products permitted for marketing to children under the WHO NPM).

-

2.

The share of products not exceeding specific nutrient or ingredient thresholds, of those products to which the respective threshold applies (e.g., share of products not exceeding the total fat threshold, of all products for which the WHO NPM defines a total fat threshold).

-

3.

The median nutrient content of products relative to the respective threshold (e.g., the median saturated fat contents of products as % of the saturated fat threshold for the respective product category).

-

4.

The share of products for each of the 22 product categories that exceed 0, 1, 2, or 3 thresholds and the mean number of thresholds exceeded in each category by those products that exceed at least one threshold.

The analysis was conducted separately for the original WHO NPM and for the WHO NPM with the adaptations proposed by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. We used the nutrient and ingredient thresholds as described in the WHO NPM manual (see Table s1 in the supplementary material), except for the trans-fatty acid threshold, which we were unable to assess due to a lack of publicly available data on the trans-fatty acid content of products on the German market (for further details, see the section on challenges below) [16]. All analyses were performed in R (the R code is shown in the online suppl. material). We used the conditional formatting function of MS Excel to create colour-coded tables for illustration purposes. In this colour-coding, shades of green stand for values that are desirable from a public health perspective (i.e., a high share of products not exceeding nutrient or ingredient thresholds), shades of red stand for less desirable values, and shades of yellow stand for values that are in-between.

Hypothetical Reformulation Scenarios

We also assessed how several hypothetical reformulation scenarios would affect the variables listed above. We defined these reformulation scenarios based on two considerations, as described in our study protocol [22]: (i) the nutrient or ingredient thresholds most commonly exceeded in the respective product category and (ii) existing reformulation commitments made by industry groups as part of Germany’s National Strategy for the Reduction of Sugar, Salt, and Fat in Processed Foods [25].

Feasibility of Applying the WHO NPM

During the research process, all authors individually took note of any difficulties or challenges in any of the steps involved in applying the WHO NPM. These were subsequently deliberated and structured by the team in several rounds of discussions. Based on these, one author (N.H.) drafted a list of challenges, which were again discussed by all authors, subsequently revised by a second author (P.v.P.) and double-checked by all remaining authors.

Results

Share of Products Permitted for Marketing to Children

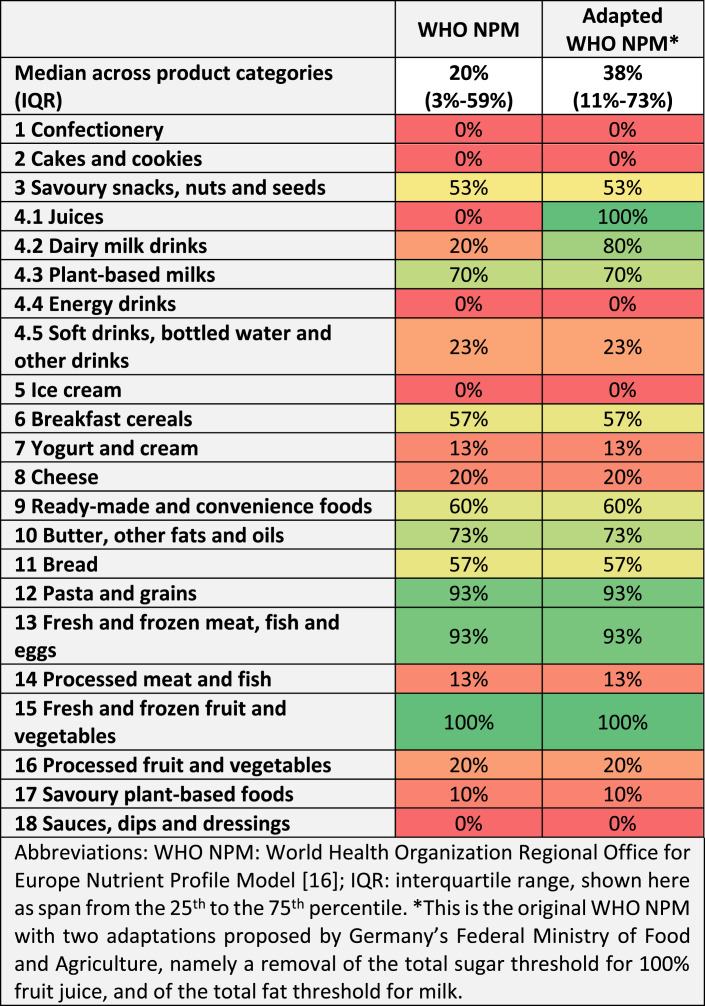

The median share of products across the 22 WHO NMP product categories that meet all nutrient and ingredient criteria and are therefore permitted for marketing to children is 20% (interquartile range (IQR) 3–59%) (see Table 1) [16]. With the adaptations to the WHO NPM announced by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, this share increases to 38% (IQR 11–73%). These adaptations increase the share of products permitted for marketing to children from 0% to 100% in the category of juices (by removing the threshold for total sugars) and from 20% to 80% in the category of milk (by removing the threshold for total fat).

Table 1.

Share of products meeting all nutrient and ingredient criteria of the WHO NPM (i.e., permitted for marketing to children)

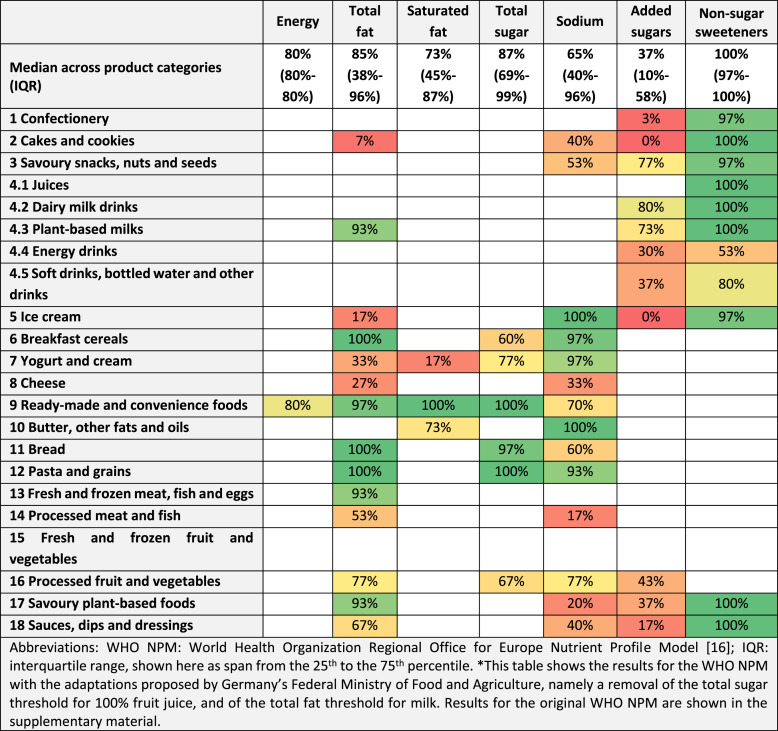

Share of Products Meeting Specific Nutrient and Ingredient Criteria

Table 2 shows the share of products meeting the respective criterion for each of the nutrient and ingredient criteria of the adapted WHO NPM. This share ranges from 100% (e.g., all breakfast cereals in our sample are below the total fat threshold for that product category) to 0% (e.g., none of the cakes and cookies in our sample meets the WHO NPM’s criterion of not containing added sugars). Across the 22 product categories, the criterion that was most commonly met was that products may not contain non-sugar sweeteners (median 100%, IQR 97–100%). In most product categories for which this criterion applies, all or almost all the products in our sample did not contain any non-sugar sweeteners and, therefore, met this criterion (the only exceptions are energy drinks, as well as soft drinks, bottled water, and other drinks). In contrast, the criterion most rarely met was the one that products may not contain added sugars (median 37%, IQR 10–58%). In most product categories to which this criterion applies, a majority of products did not meet it, meaning they contained added sugars (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Share of products meeting the adapted WHO NPM’s nutrient and ingredient criteria*

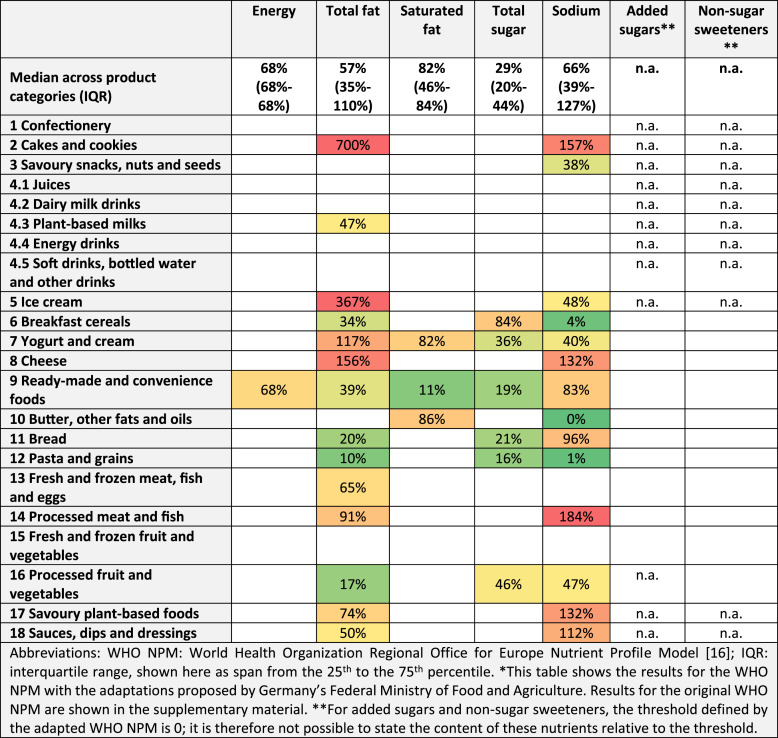

Average Nutrient Content

Table 3 shows the median nutrient content of products relative to the respective threshold. In most product categories, the median content of energy, fat, sugar, and sodium is below the relevant threshold defined by the WHO NPM. For example, the median content of total sugars in breakfast cereals in our sample stands at 84% of the total sugars threshold of the WHO NPM (which is 12.5 g/100 g, see Table 3). In contrast, the total fat content of cakes and cookies stands at 700% of the WHO NPM’s threshold (which is 3 g/100 g).

Table 3.

Median content relative to the adapted WHO NPM’s nutrient and ingredient thresholds*

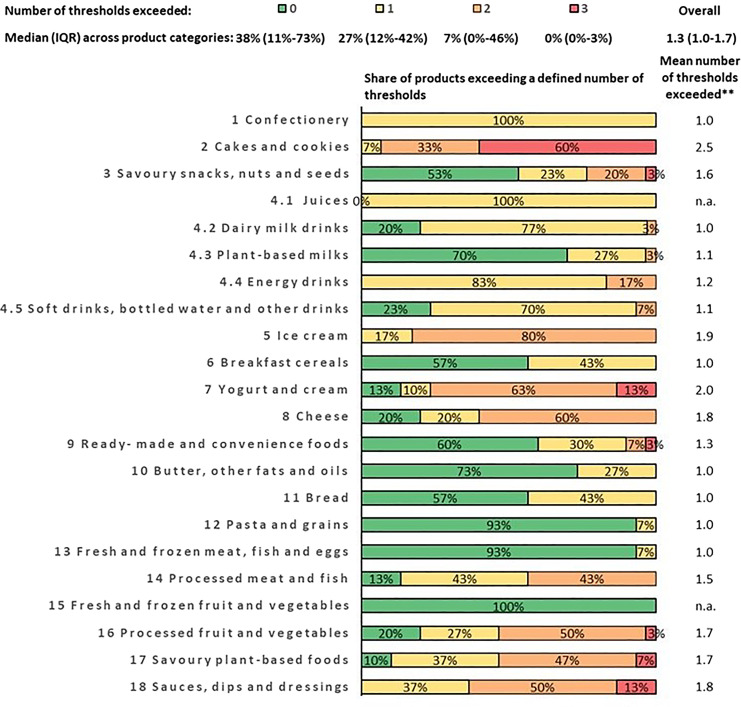

Number of Thresholds Exceeded

In most of the product categories, a majority of products either do not exceed any threshold or only exceed one threshold (median shares of 38% and 27% for all products, respectively, see Fig. 1). Consequently, in most of the product categories, the share of products exceeding two thresholds (median 7%) or three thresholds (median 0%) is low. None of the products in our sample exceeded more than three thresholds. There was only one product category in which a majority of products exceeded three thresholds: among the cakes and cookies in our sample, 60% of products exceeded three thresholds (mostly those for total fat, sodium, and added sugars).

Fig. 1.

Share of products exceeding a specific number of nutrient and ingredient thresholds.

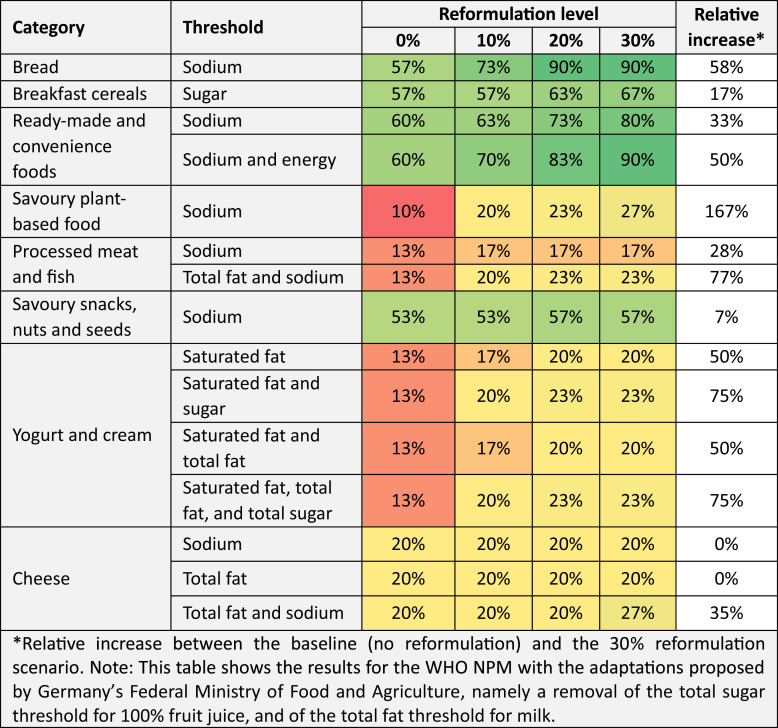

Specific Reformulation Scenarios

We defined 15 reformulation scenarios for 8 product categories (see Table 4). In some product categories, a modest reduction in a single nutrient is sufficient to substantially increase the share of products permitted for marketing to children under the WHO NPM. For example, a 20% reduction of the sodium content of bread raises the share of products permitted for marketing to children in that category from 57% to 90%. In other product categories, the effects of reformulation are less pronounced; for example, for the category of savoury snacks, nuts, and seeds, a 30% reduction in the sodium content increases the share of products permitted for marketing to children from 53% to 57%, a relative increase of 7% (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of specific reformulation scenarios on the share of products permitted for marketing to children (in %)

Experiences in Applying the WHO NPM and Challenges Encountered

We encountered three main challenges in applying the WHO NPM to our sample of products from the German market. Specifically, we found that for some products and some nutrient and ingredient criteria, the nutrient and ingredient information provided on the packages of food and beverage products in Germany is not sufficient to determine whether the respective criterion is met. Specifically, this refers to: (i) the trans-fatty acid content of products; (ii) the nutrient content of products currently not required to display nutrient declarations on their packages (such as fresh meat); and (iii) the nutrient content of products prepared by the consumer with dry mixes, powders, or concentrates. A detailed description of these challenges and how we addressed them in our analysis is provided in the online supplementary material. Several other challenges related to the assignment of products to product categories are also described in the online supplementary material.

Discussion

Key Findings

Applying the WHO NPM as proposed by the WHO Regional Office for Europe to our random sample of 660 food and beverage products on the German market, the median share of products across the model’s 22 product categories that meet all its nutrient and ingredient criteria, and would therefore be permitted for marketing to children, is 20% (IQR 3–59%). With the introduction of model adaptations announced by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture in the context of the model’s planned use in Germany, this figure increases to 38% (IQR 11–73%). The product categories in which the highest share of products meets all criteria of the adapted WHO NPM are fresh and frozen fruit and vegetables (100% of all products in our sample), fruit juices (100%), fresh and frozen meat, fish and eggs (93%), pasta and grains (93%), and dairy milk drinks (80%). By contrast, none of the products in our sample met the WHO NPM’s nutrient and ingredient criteria in the categories of confectionery, cakes and cookies, energy drinks, ice cream, and sauces, dips and dressings.

Most products that exceed at least one threshold defined by the WHO NPM (and are therefore not permitted for marketing to children) exceed only one of the model’s seven nutrient and ingredient thresholds (the median across the 22 product categories of the mean number of thresholds exceeded is 1.3). This suggests that in many cases, a targeted reduction in only one or two nutrients of concern would be sufficient to raise the share of products permitted for marketing to children. Indeed, with targeted reformulation (assuming a 30% reduction in fat, sugar, sodium, and/or energy) the share of products permitted for marketing to children increases substantially (defined as a relative increase by at least 50%) in several product categories (including bread, processed meat, yogurt and cream, ready-made and convenience foods, and savoury plant-based foods). In other product categories, however, the effects of reformulation are less pronounced. This applies in particular to product categories for which the WHO NPM defines a threshold for added sugars of zero (this includes confectionery, cakes and cookies, energy drinks, soft drinks, bottled water and other drinks, ice cream, processed fruit and vegetables, and sauces, dips and dressings); in these product categories, it would be necessary to replace added sugars completely with other ingredients to increase the share of products permitted for marketing to children substantially. Indeed, the added sugars threshold is the WHO NPM’s most commonly exceeded threshold, and the only threshold for which more than half of all products in most product categories are above the threshold defined by the WHO NPM. By contrast, for all other nutrient and ingredient thresholds, in most product categories, a majority of products are below the respective threshold.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. It is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study applying the WHO NPM to a sample of products from the German market. We examine several questions of critical relevance to the ongoing policy-making process regarding the proposed new legislation regulating food and beverage marketing directed towards children in Germany [11]. Our study is based on a random sample of products from Open Food Facts, a large, publicly available food and beverage database, and we implemented a number of quality assurance procedures. Our study follows the STROBE and STROBE-nut reporting guidelines and is based on an a priori protocol, which we developed and registered publicly before we conducted our analyses [22]. Finally, our manuscript’s online supplementary material includes a detailed description of methods, data, and code, ensuring transparency and allowing for the reproducibility of our research.

Besides these strengths, our study has some limitations. The products contained in the Open Food Facts database are not necessarily representative of the German market overall, and we were unable to account for the market share of different products (e.g., by conducting separate analyses for top-selling products). While we found the nutrient and ingredient data provided by Open Food Facts to be reasonably reliable, our spot checks revealed that for some products, data differed from the product data provided on the manufacturers’ websites, indicating that for some products, Open Food Facts may provide outdated information. Moreover, owing to resource limitations, our analysis was limited to 30 products per category, and a larger number of products may have yielded results with a higher precision. Finally, we were not able to assess the actual effects of the proposed legislation on advertisement exposure, dietary intake, or disease risk, given the fact that the legislation has not yet been implemented.

Comparison with Similar Studies

The 2023 WHO NMP was originally pilot tested in 2022 in 13 European countries (Belgium, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, and Romania) in an evaluation of 108,578 products [16]. In this analysis, the median share of products that met the WHO NPM criteria was 23% (IQR 4–51%), comparable to our results for the WHO NPM without adaptations (median of 20%, IQR 3–59%). On the level of the WHO NPM’s 22 product categories, results are also similar for many product categories but differ more strongly for others (for a detailed comparison, see Table s8 in the supplementary material). This applies, for example, to the category of savoury snacks, nuts, and seeds (53% below all thresholds in our sample vs. 2% in the WHO pilot test). One reason for this discrepancy could be the fact that our sample included a substantial number of plain, unsalted nuts and seeds. Another example is breakfast cereals (57% of all products below all thresholds in our sample vs. 18% in the WHO pilot test). This may be explained by that our sample included a substantial number of breakfast cereals consisting mostly of plain oats, dried fruit, nuts, and seeds, most of which qualified as healthy under the WHO NPM. More generally, the differences in the results between the two analyses may be attributable to two factors: firstly, our sample in each category was relatively small and may therefore be more susceptible to random variation (as mentioned in the section above); and secondly, country-specific differences, including differences in food traditions and consumer preferences.

Policy Implications

Overall, we found that the application of the WHO NPM to products on the German market is feasible. We encountered only minor practical challenges, which could be addressed through appropriate adaptations and procedural provisions. Specifically, the application of the threshold for trans-fatty acids would be challenging in Germany unless new rules on the declaration of trans-fatty acids were introduced; however, this would require changes to EU regulation [26]. Moreover, provisions are needed to determine the nutrient content of products that are currently not required to show nutrient declarations on their packages (such as fresh, unprocessed meat, fish, and similar products) [26, 27]. The same applies for the nutrient content of foods prepared by the final consumer from concentrates or dry mixes (such as beverage powders and baking mixes). In some cases, more detailed guidance on the assignment of products to product categories would be helpful.

Regarding milk, Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture announced that it is planning to adapt the WHO NPM by not applying its threshold for total fat (which is 3 g/100 mL), thus allowing marketing for milk with a higher fat content [20]. In our analysis, this adaptation increased the share of permitted products in the respective category of the WHO NPM (dairy milk drinks) considerably, from 20% to 80%. For consistency, it may be worth considering extending this adaptation to category 4.3 (plant-based milk), and to category 7 (yogurt, sour milk, cream and similar foods), for which the WHO NPM currently also defines thresholds for total fat of 3 g per 100 mL (for yogurt and similar products it additionally defines a threshold for saturated fat of 1 g per 100 mL) [16]. In our sample of products, the removal of these thresholds would raise the share of products permitted for marketing to children in the category of plant-based milk from 70% to 73%, and in the category of yogurt, sour milk, cream and similar foods from 13% to 73%.

Regarding the stringency of the WHO NPM, we found that in most product categories, a substantial number of products in our sample met all nutrient and ingredient criteria defined by the WHO NPM and could still be advertised to children under Germany’s proposed new food marketing regulation. This suggests that the proposed new legislation would not ban food marketing per se (as claimed by some critics [15, 18]) and that food marketing efforts could be redirected towards existing products with a lower content of sugar, sodium, and fat, as intended by the government [19]. In several product categories frequently consumed by children (based on dietary survey data [28]), the share of products meeting the criteria of the WHO NPM is, however, low. This includes, among others, confectionery, cakes and cookies, soft drinks, and ice cream. This suggests that in these product categories, the proposed legislation may reduce overall marketing pressure on children.

Our analysis of reformulation scenarios shows that in several product categories, the share of permitted products could be increased substantially through moderate reductions in the content of fat, sugar, sodium, and/or energy. This suggests that the use of the WHO NPM in the proposed new marketing regulation in Germany could indeed provide incentives for reformulation, as hoped for by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture [19].

Conclusions

The application of the WHO NPM to food and beverage products on the German market was found to be feasible. Challenges encountered in the application of the WHO NPM in its current form in Germany could be addressed with appropriate adaptations and provisions. The share of products that meet all criteria defined by the WHO NPM and are therefore permitted for marketing to children under the model (and would be allowed for marketing under the new German law) varies considerably by product category. In most, but not all product categories, this share is substantial. In several product categories, the share of products permitted for marketing to children could be increased substantially with targeted reformulation. The use of the WHO NPM in the context of the proposed new legislation on food marketing in Germany seems feasible. It seems plausible that it will serve its intended public health objective of limiting marketing in a targeted manner specifically for less healthy products, and possibly also of incentivising reformulation in some product categories.

Acknowledgment

We thank Cody Holliday for their generous support with data management and analysis.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement was not required for this study type, no human or animal subjects or materials were used.

Conflict of Interest Statement

PvP reports receiving research funding from Germany’s Federal Ministries of Food and Agriculture (BMEL), Education and Research (BMBF) and the Environment and Consumer Protection (BMUV), as well as travel costs and speaker and manuscript fees from the German and Austrian Nutrition Societies (DGE and ÖGE), the German Diabetes Society (DDG), and the German Obesity Society (DAG). OH is an employee of the German Diabetes Society (DDG) and the German Obesity Society (DAG) and has previously been an employee of foodwatch. CK reports being a member of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) and the BerufsVerband Oecotrophologie e.V. (VDOE). ER reports receiving research funding from Germany’s Federal Ministries of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) and Education and Research (BMBF). The staff positions of NH, AL, CK, EO, KG, and PvP are partly or fully funded through research grants from Germany’s Federal Ministries of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) and Education and Research (BMBF). The other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was conducted without external funding through staff positions at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU Munich), Germany, and the German Obesity Society (DAG), Berlin, Germany.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.v.P. and O.H; methodology: P.v.P., O.H., N.H., A.L., C.K., and E.R; investigation: N.H., A.L., P.v.P., C.K., E.O., and K.G; data curation: NH and AL; formal analysis: A.L. and N.H; writing – original draft: P.v.P. and N.H; writing – review and editing: N.H., A.L., O.H., C.K., E.O., K.G., E.R., and P.v.P; supervision: P.v.P.

Funding Statement

This work was conducted without external funding through staff positions at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU Munich), Germany, and the German Obesity Society (DAG), Berlin, Germany.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/bjevc. Additional information is provided in the supplementary material published online alongside this article. Registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) after data were extracted, but before analyses were conducted at https://osf.io/bjevc [22]. Differences between the protocol and the study are explained in the online supplementary material. An earlier version of this manuscript has been published as preprint on medRxiv at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.24.23288785 [29]. Differences between the preprint and the final manuscript are explained in the online supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B, Tudur-Smith C, Jones A, Halford JC, et al. Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):519–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sadeghirad B, Duhaney T, Motaghipisheh S, Campbell NR, Johnston BC. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Rev. 2016;17(10):945–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith R, Kelly B, Yeatman H, Boyland E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: a systematic critical review. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. von Philipsborn P. Scientific evidence in nutrition policy. Ernahrungs Umschau. 2022;69(1):10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yau A, Berger N, Law C, Cornelsen L, Greener R, Adams J, et al. Changes in household food and drink purchases following restrictions on the advertisement of high fat, salt, and sugar products across the Transport for London network: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Med. 2022;19(2):e1003915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly B, Vandevijvere S, Ng S, Adams J, Allemandi L, Bahena-Espina L, et al. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes Rev. 2019;20(Suppl 2):116–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Effertz T. Kindermarketing für ungesunde Lebensmittel in Internet und TV. 2021; (April 6, 2023). Available from: https://www.bwl.uni-hamburg.de/irdw/dokumente/kindermarketing2021effertzunihh.pdf.

- 8.statista. Entwicklung der Bruttowerbeaufwendungen für Süßwaren in Deutschland in den Jahren 2017 bis 2021. 2023; (April 6, 2023). Available from: https://de.statista.com/prognosen/197004/werbeausgaben-fuer-schokolade-und-zuckerwaren-in-deutschland-seit-2000.

- 9.statista. Werbeausgaben für Früchte und Gemüse in Deutschland in den Jahren 2007 bis 2017. 2023; (April 6, 2023). Available from: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/388528/umfrage/werbeausgaben-fuer-fruechte-und-gemuese-in-deutschland/.

- 10. Bundesverband AOK, Bundesverband V, Deutsche Allianz Nichtübertragbare Krankheiten . Policy Brief: kindermarketing für Lebensmittel | Vorschlag zur Ausgestaltung der Werbebeschränkung. 2022. July 18, 2022). Available from: https://www.dank-allianz.de/files/content/projekte/kindermarketing/2022-02-10_AOK_vzbv_DANK_policy-brief-kindermarketing_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mehr BMEL. Kinderschutz in der Werbung: pläne für klare Regeln zu an Kinder gerichteter Lebensmittelwerbung. 2023. April 4, 2023). Available from: https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/ernaehrung/gesunde-ernaehrung/kita-und-schule/lebensmittelwerbung-kinder.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Global Food Research Program at UNC-Chapel Hill . National policies regulating food marketing to children. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breites DAG. Bündnis um Starkoch Jamie Oliver fordert umfassenden Schutz von Kindern gegen Junkfood-Werbung. (April 6, 2023). Available from: https://adipositas-gesellschaft.de/breites-bundnis-um-starkoch-jamie-oliver-fordert-umfassenden-schutz-von-kindern-gegen-junkfood-werbung/. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kinderschutz DAG. der Lebensmittelwerbung: experten fordern Unterstützung der Ampel-Koalition für Özdemirs Pläne; 2023. April 6, 2023). Available from: https://adipositas-gesellschaft.de/kinderschutz-in-der-lebensmittelwerbung-experten-fordern-unterstuetzung-der-ampel-koalition-fuer-oezdemirs-plaene/. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Ernährungsindustrie . Warum ein Werbeverbot allen schadet. 2023. April 5, 2023). Available from: https://www.bve-online.de/themen/die-ernaehrungsindustrie/warum-ein-werbeverbot-allen-schadet. [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO . WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model. 2nd ed; 2023. (March 10, 2023). Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2023-6894-46660-68492. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kapalschinski C. Werbeverbot für Süßes und Fettes? FDP rügt Özdemirs Plan als „weltfremd“. Welt.; 2023. p. 2023. Available from: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article244003051/Werbeverbot-fuer-Suessigkeiten-FDP-ruegt-Oezdemirs-Plan-als-weltfremd.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18. ZAW. Keine Evidenzbasierte Politik . BMEL kündigt weitgehendes Totalwerbeverbot für Lebensmittel an; 2023. April 18, 2023). Available from: https://zaw.de/keine-evidenzbasierte-politik-bmel-kuendigt-weitgehendes-totalwerbeverbot-fuer-lebensmittel-an/. [Google Scholar]

- 19. FAQs BMEL. . Zum Gesetzentwurf für an Kinder gerichtete Lebensmittelwerbung. 2023. April 5, 2023). Available from: https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/FAQs/DE/faq-lebensmittelwerbung-kinder/faq-lebensmittelwerbung-kinder_List.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Entwurf BMEL. eines Gesetzes zum Schutz von Kindern vor Werbung für Lebensmittel mit hohem Zucker-, Fett- oder Salzgehalt (Kinder-Lebensmittel-Werbegesetz – kwg). 2023. Available from: https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Meldungen/DE/Presse/2023/230303-kinderschutz-werbung.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Open Food Facts. Open Food Facts: Deutschland. 2023; (April 4, 2023). Available from: https://de.openfoodfacts.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holliday N, Leibinger A, Huizinga O, Klinger C, Okanmelu E, Geffert K, et al. Application of the WHO nutrient profile model to a sample of products on the German market. Open Sci Framework. 2023:2023. [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lachat C, Hawwash D, Ocké MC, Berg C, Forsum E, Hörnell A, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology: nutritional epidemiology (STROBE-nut): an extension of the STROBE statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13(6):e1002036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nationale BMEL. Reduktions- und Innovationsstrategie: weniger Zucker, Fette und Salz in Fertigprodukten. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26. EU. Nutrition declaration. 2023; (April 5, 2023). Available from: https://europa.eu/youreurope/business/product-requirements/food-labelling/nutrition-declaration/index_en.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bundeszentrum für Ernährung . Nährwertkennzeichnung: pflichten und freiwillige Informationen; 2023. ; (April 5, 2023). Available from: https://www.bzfe.de/lebensmittel/einkauf-und-kennzeichnung/kennzeichnung/naehrwertkennzeichnung. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mensink GBM, Haftenberger M, Lage Barbosa C, Brettschneider A-K, Lehmann F, Frank M, et al. EsKiMo II: die ernährungsstudie als KiGGS-modul Robert Koch-Institut; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holliday N, Leibinger A, Huizinga O, Klinger C, Okanmelu E, Geffert K, et al. Application of the WHO Nutrient Profile Model to products on the German market: implications for proposed new food marketing legislation in Germany. medRxiv. 2023;24:23288785. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/bjevc. Additional information is provided in the supplementary material published online alongside this article. Registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) after data were extracted, but before analyses were conducted at https://osf.io/bjevc [22]. Differences between the protocol and the study are explained in the online supplementary material. An earlier version of this manuscript has been published as preprint on medRxiv at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.24.23288785 [29]. Differences between the preprint and the final manuscript are explained in the online supplementary material.