Summary

Background

Focused ultrasound (FUS) combined with microbubbles is a promising technique for noninvasive, reversible, and spatially targeted blood-brain barrier opening, with clinical trials currently ongoing. Despite the fast development of this technology, there is a lack of established quality assurance (QA) strategies to ensure procedure consistency and safety. To address this challenge, this study presents the development and clinical evaluation of a passive acoustic detection-based QA protocol for FUS-induced blood-brain barrier opening (FUS-BBBO) procedure.

Methods

Ten glioma patients were recruited to a clinical trial for evaluating a neuronavigation-guided FUS device. An acoustic sensor was incorporated at the center of the FUS device to passively capture acoustic signals for accomplishing three QA functions: FUS device QA to ensure the device functions consistently, acoustic coupling QA to detect air bubbles trapped in the acoustic coupling gel and water bladder of the transducer, and FUS procedure QA to evaluate the consistency of the treatment procedure.

Findings

The FUS device passed the device QA in 9/10 patient studies. 4/9 cases failed acoustic coupling QA on the first try. The acoustic coupling procedure was repeatedly performed until it passed QA in 3/4 cases. One case failed acoustic coupling QA due to time constraints. Realtime passive cavitation monitoring was performed for FUS procedure QA, which captured variations in FUS-induced microbubble cavitation dynamics among patients.

Interpretation

This study demonstrated that the proposed passive acoustic detection could be integrated with a clinical FUS system for the QA of the FUS-BBBO procedure.

Funding

National Institutes of Health R01CA276174, R01MH116981, UG3MH126861, R01EB027223, R01EB030102, and R01NS128461.

Keywords: Passive acoustic detection, Quality assurance, Blood-brain barrier opening, Focused ultrasound, Clinical FUS device, Acoustic coupling

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

More than 20 clinical trials are recruiting patients to evaluate the focused ultrasound combined with microbubble-induced BBB opening technique in patients with various diseases (e.g., glioma, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease). With the increasing number of clinical studies, there is a growing need to develop and evaluate quality assurance (QA) protocols to ensure consistent and safe operation of the procedure.

Added value of this study

This study developed a passive acoustic detection-based QA protocol for ensuring the proper functioning of the FUS device, maintaining high-quality acoustic coupling, and evaluating the consistency of the treatment procedure.

Implications of all the available evidence

The proposed QA protocol offers a systematic and quantifiable approach to conduct QA across multiple aspects of FUS procedures. This includes assessing the functionality of clinical FUS devices before each procedure (FUS device QA), evaluating the quality of acoustic coupling (acoustic coupling QA), and monitoring the process of FUS-induced BBB opening (FUS procedure QA). This QA protocol provides a vital tool to ensure the consistency, efficiency, and safe execution of FUS-induced BBB opening. Establishing QA protocols is critical to advancing the FUS-induced BBB opening technique in the clinic.

Introduction

The application of focused ultrasound (FUS) combined with microbubbles to transiently induce blood-brain barrier (BBB) opening (FUS-BBBO) holds great promise for the treatment and diagnosis of brain diseases. This technique uses FUS in combination with microbubbles to generate mechanical forces on the BBB through microbubble cavitation (i.e., the expansion, contraction, and collapse of microbubbles). These mechanical forces result in noninvasive and reversible opening of the BBB at the FUS-targeted brain region.1 FUS-BBBO allows therapeutic agents to cross from the bloodstream into the brain for noninvasive and localized brain drug delivery, exhibiting substantial potential in the treatment of brain diseases with encouraging outcomes in preclinical studies2,3 and clinical trials.4, 5, 6 FUS-BBBO, in the meantime, can enhance the release of brain disease-specific biomarkers (e.g., DNA, RNA, and proteins) from the FUS-targeted brain location into the blood circulation for noninvasive and localized molecular diagnosis of brain diseases, a technique called sonobiopsy.7, 8, 9, 10 Overall, FUS-BBBO enables “two-way trafficking” between the brain and bloodstream to benefit the development of effective therapeutic approaches and advance the diagnosis of brain diseases. With the increasing number of FUS-BBBO clinical studies, there is a growing need to develop and evaluate quality assurance (QA) protocols to ensure consistent and safe operation of the procedure. QA aims to address imperfections in the setup to attain optimal outcomes by evaluating quality and identifying problems and issues. It is important to note that QA procedures have been established for high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) devices primarily used for thermal ablation applications.11,12 However, there are no reported studies on establishing and evaluating QA protocols specifically designed to ensure consistent and safe operation of the FUS-BBBO procedure.

Magnetic resonance image (MRI)-guided FUS device and neuronavigation-guided FUS device have been used in FUS-BBBO clinical studies.13, 14, 15 Without a systematic and quantifiable approach to evaluate FUS devices before each procedure, the functionality of the FUS system cannot be guaranteed. As a result, the consistency and safety of the procedure cannot be assured. Conducting a mandatory examination of the FUS device before clinical procedures is crucial, as malfunctions can occur during clinical applications.16,17 The widely recognized QA approach, the “gold-standard” method, involves measuring the FUS transducer's three-dimensional (3D) acoustic pressure fields using a hydrophone.18 These measurements are typically conducted in controlled “free-field” conditions, employing degassed, filtered, and deionized water. A calibrated hydrophone is utilized to scan across the acoustic field using a three-dimensional positioning system controlled by high-precision stepper motors for accurate acoustic pressure measurements. However, conducting this standard device QA approach takes several hours and requires expertise in hydrophone measurements. Although this gold standard QA is critically needed, it is impractical to use it for regular device QA before each procedure. Hence, a convenient QA approach that can be easily performed to assess the functionality of clinical FUS devices before each procedure is needed.

Alongside verifying the functionality of clinical FUS devices, there is a critical need to ensure high-quality acoustic coupling. Insufficient acoustic coupling, mainly due to the presence of bubbles in the coupling medium, can impede the effective transmission of FUS energy. Inadequate acoustic coupling can stem from insufficient degassed ultrasound gel, air bubbles trapped during gel application on the patient's head, or inadequate degassing of the water bladder attached to the FUS transducer. In such situations, it becomes crucial to have a means of evaluating the quality of acoustic coupling. However, only a few studies specifically focused on assessing the quality of acoustic coupling. Morchi et al. introduced a quantitative acoustic coupling coefficient for assessing acoustic coupling in ultrasound-guided FUS procedures.19 This coefficient was computed from the reflected radiofrequency data using a frequency analysis method. It was tested under various acoustic coupling conditions to determine the acoustic coupling coefficient corresponding to the adequacy of the coupling. Although promising, this approach is not practical for clinical application because it requires the threshold for acoustic coupling coefficient to be determined for each procedure. Kamimura et al. used passive cavitation detection to evaluate the acoustic coupling quality of FUS-induced BBB opening in non-human primates.20 Passive cavitation detection is an established technique, which uses an ultrasound sensor to passively listen to acoustic emissions generated by bubble oscillation during ultrasound sonication. These acoustic emissions are characterized by the presence of harmonic and subharmonic signals at relatively lower FUS acoustic pressures and the presence of broadband signals at relatively higher acoustic pressures. They observed that insufficient coupling often correlated with the presence of broadband spectrum and sharp variations in the harmonic and ultra-harmonic components of the signal. Passive cavitation detection offers a promising solution for acoustic coupling checks. However, no clinical study has been reported on evaluating the application of passive cavitation detection for acoustic coupling QA in a FUS-BBBO procedure.

Furthermore, achieving consistent FUS sonication for BBB opening presents another challenge. The fundamental physical mechanism of FUS-BBBO is microbubble cavitation. Variations in the in situ acoustic pressure and microbubble concentration in the FUS focal region among patients and different brain locations in the same patient21, 22, 23 contribute to changes in microbubble cavitation activity. The in situ acoustic pressure can vary due to factors such as skull heterogeneity and changes in the incident angle of the FUS beam relative to the skull during the procedure.24,25 Variances in microbubbles stem from differences in size distribution and concentration within the FUS focal region, influenced by factors such as vascular density, vessel size, and blood flow speed.21, 22, 23 Passive cavitation detection has been used in clinical FUS devices for real-time monitoring of microbubble cavitation activity.6,13, 14, 15,26, 27, 28 However, no clinical study has been reported specifically on using passive cavitation detection as a QA procedure to evaluate the consistency of the FUS-BBBO procedure.

To address the challenges mentioned above, there is a pressing need for a QA strategy that is capable of assessing the performance of clinical FUS devices before each procedure (FUS device QA), evaluating the quality of acoustic coupling (acoustic coupling QA), and monitoring the FUS-BBBO procedure (FUS procedure QA). This study presents the development and clinical evaluation of a passive acoustic detection (PAD)-based QA protocol to achieve these functions. The FUS device QA was performed before each FUS-BBBO procedure using a QA phantom. The PAD sensor received the FUS signal reflected from the phantom to evaluate the performance of the FUS device. The acoustic coupling QA was performed after the subject's head was coupled with the FUS device through the acoustic coupling medium. PAD signals were acquired with FUS sonication to detect air bubbles trapped in the coupling medium based on the detection of air bubble cavitation signals. For the FUS procedure QA, the FUS-BBBO procedure was monitored by the PAD sensor, and the acquired signals were analyzed in realtime to assess the consistency of the procedure based on the detection of microbubble cavitation signals. We tested our proposed QA protocol in a clinical study conducted on glioma patients. It is noted that we used the term PAD to encompass both the passive detection of reflected FUS signals from the QA phantom and the passive detection of cavitation signals.

Methods

Ethics

The clinical study was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis Institute Review Board (HRPO# 202202025) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05281731). All subjects underwent the full process of informed consent with Institute Review Board approved informed consent forms signed and retained.

Study design

This prospective single-arm trial aimed to assess the feasibility and safety of sonobiopsy in patients with glioma using a neuronavigation-guided FUS device. Before enrollment, all subjects provided written informed consent. Glioma patients scheduled for surgical tumor removal were screened for the clinical trial. Ten patients (seven males and three females; average age 60 years; range 36–74 years) met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the trial. The sonobiopsy procedure was performed on the scheduled surgery day right before surgical tumor removal.

FUS device and workflow

The FUS transducer used in this study comprised 15 annular-ring transducers manufactured by Imasonics (Voray-sur-l'Ognon, France). This transducer had a center frequency of 650 kHz, an aperture size of 65 mm, and a focal distance of 65 mm (f-number of 1). The FUS transducer was driven by an electronic transmitting system (Image Guided Therapy, Pessac, France). A water bladder was attached to the FUS transducer with an inlet and outlet for degassing the water. The output of the FUS transducer was calibrated using a hydrophone (HGL-0200, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) connected with a pre-amplifier (AG-20X0, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in a water tank using our previous established procedure29 and the acoustic pressure at the FUS transducer focus was measured and reported in this study.

For each FUS-BBBO procedure, we followed the same protocol as reported before.30 The patient was under anesthesia, and the patient's head was stabilized by the Mayfield head holder (Integra LifeSciences, Princeton, NJ, USA). The head holder was connected to the surgical table through a Mayfield bed attachment. The stealth arc and Veltek arm were connected, and the patient's head was registered based on the pre-acquired MRI/CT images. The planned FUS trajectory was then entered into the neuronavigation system (Medtronic plc., Dublin, Ireland). After the registration and the FUS trajectory were determined, the patient's hair above the target location was shaved, and the exposed skin was thoroughly cleaned with alcohol pads. Degassed ultrasound gel was applied liberally to the exposed skin area. The FUS transducer was then positioned under the guidance of the neuronavigation system. To ensure alignment of the central axis of the FUS transducer with the neuronavigation tracker, a passive blunt probe (Stealth S8, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was affixed to the rear of the FUS transducer using a customized adapter. The neuronavigation software incorporated an offset along the probe's trajectory to accurately indicate the location of the FUS focal point. For the transducer preparation, deionized water was filled into the transducer's water bladder and degassed with a degassing system for more than 15 min before use.

The FUS sonication used the following parameters: center frequency = 650 kHz (), pulse repetition frequency = 1 Hz, pulse duration = 10 ms (i.e., duty cycle = 1%), and different acoustic pressure values (Table 1). Fifteen seconds after FUS sonication began, microbubbles (Definity, Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA, USA) were administered intravenously by the standing anesthesiologist at a dose of 10 μL/kg body weight diluted with saline following the manufacturer's instruction. The injection rate was controlled with the best effort to be ∼10 s/mL as recommended by the manufacturer. Prior to each FUS-BBBO procedure, we conducted a full-wave acoustic simulation using the k-Wave toolbox. This simulation was integral to our treatment planning, allowing us to estimate the ultrasound pressure field distribution within the skull and calculate skull attenuation, utilizing methods outlined in our previous publication.25 Sonication was ended at 3 min after the initial detection of microbubble signals.

Table 1.

Summary of FUS procedure parameters, harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband signal quantification results (MB: microbubble; NA: not applicable; NP: not present).

| Patient ID | Predicted in situ pressure (MPa) | MB injection duration (s) | MB injection volume after dilution (mL) | Harmonic onset time (s) | Harmonic duration (s) | Harmonic dose (a.u.) | Sub-harmonic dose (a.u.) | Broadband dose (a.u.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 01 | 0.47 | 35 | 5.3 | 51 | 189 | 4.08 | 0.47 | 0.95 |

| Patient 02 | 0.31 | 77 | 8.2 | 60 | 74 | 1.81 | 0.25 | 3.68 |

| Patient 03 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Patient 04 | 1.03 | 66 | 7.8 | 27 | 154 | 28.9 | 116.8 | 185.2 |

| Patient 05 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Patient 06 | 0.66 | 15 | 8.6 | 214 | 33 | 2.31 | 10.4 | 88.9 |

| Patient 07 | 0.53 | 133 | 6.8 | 80 | 162 | 20.6 | 150.9 | 123.1 |

| Patient 08 | 0.40 | 72 | 9 | 126 | 97 | 4.11 | 0.68 | 1.34 |

| Patient 09 | 0.34 | 57 | 5.3 | NP | NP | NP | NP | NP |

| Patient 10 | 0.30 | 62 | 7.4 | 62 | 154 | 2.81 | 1.38 | 3.25 |

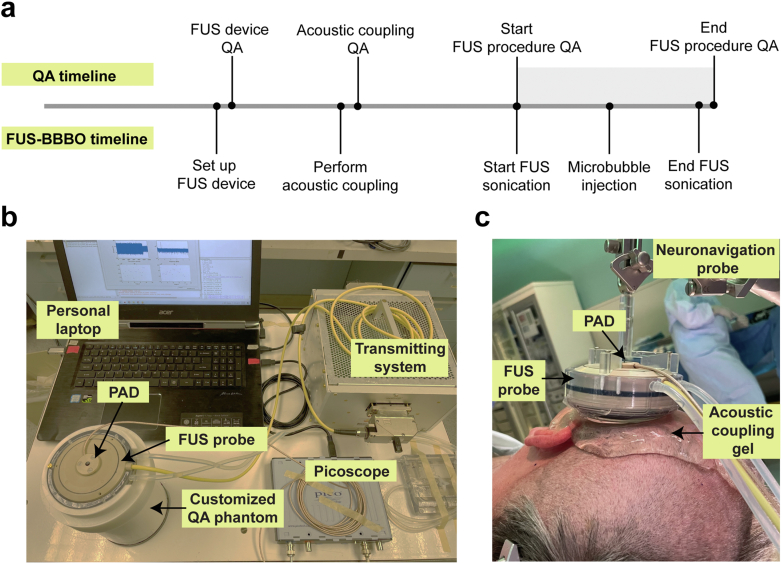

All QA procedures used a single-element acoustic sensor for PAD. The sensor was a circular-shaped planar ultrasound transducer with an active element size of 4.5 mm, a center frequency of 650 kHz, and a −6 dB bandwidth of 260 kHz (Imasonics, Voray-sur-l'Ognon, France). It was inserted through the central hole of the FUS transducer and aligned confocal with the FUS probe. A PicoScope (5244B, Pico Technology, Cambridgeshire, UK) was used to capture the detected PAD signals to a personal laptop (Fig. 1b). The data acquisition was synchronized with FUS sonication. The PicoScope was configured to operate at a sampling rate of 40 MHz. Our previous studies8,31 and the work of other research groups20,32 have successfully employed this PAD system for effective cavitation detection during FUS-BBBO. A customized MATLAB script was written to process the acquired PAD signals. The proposed QA protocol consists of three procedures: FUS device QA, acoustic coupling QA, and FUS procedure QA. Fig. 1a shows the workflow for the QA protocol.

Fig. 1.

FUS device with passive acoustic detection. (a) FUS-BBBO procedure workflow with QA. (b) The experimental setup includes a FUS probe, passive acoustic detection (PAD) sensor, and QA phantom. The FUS probe was connected to the transmitting system, and the PAD sensor was connected to a laptop through the Picoscope. (c) Picture of the FUS probe attached to the neuronavigation probe and the setup for the acoustic coupling during the FUS-BBBO procedure in a patient.

FUS device QA protocol

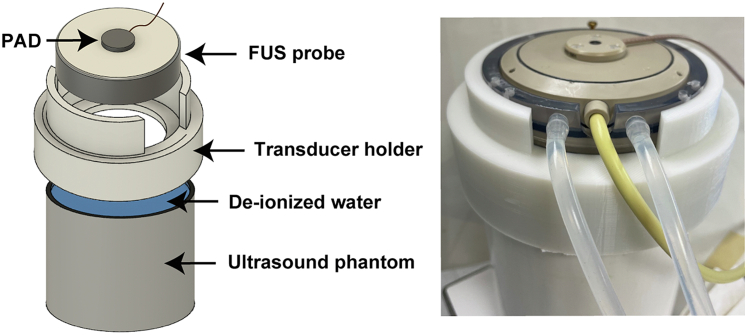

FUS device QA was performed before the FUS-BBBO procedure started. A customized QA phantom (Fig. 2) was manufactured by attaching a 3D-printed FUS transducer holder to the top of a commercial ultrasound phantom (CIRS Technology, Norfolk, VA, USA). Deionized water was poured into the gap between the 3D-printed holder and the ultrasound phantom to serve as the acoustic coupling medium. FUS sonication was applied on the QA phantom with 0.3 MPa (free-field acoustic pressure) for 20 s. The reflected FUS signals from the ultrasound phantom were detected by the PAD, and the amplitude of the detected PAD signals was evaluated. The FUS device was considered to pass the FUS device QA if the amplitude of the detected PAD signal was located within the passing zone. The passing zone was defined by the mean of the pre-acquired amplitude of the detected PAD signals ± tolerance range. The pre-acquired amplitude of the detected PAD signals was repeated measurements using the same setup before the FUS-BBBO procedure. It is noted that before the FUS-BBBO procedure, the device was measured regularly using the QA phantom to ensure consistent performance of the device. In the event of a device failure, troubleshooting was conducted until the issue was successfully resolved, and the device was measured again using the phantom to establish the passing zone. The reference level would need to be re-established when device failure occurs. The tolerance range was defined by two times the standard deviation of pre-acquired measurements.

Fig. 2.

FUS device QA setup. The design of the customized QA phantom includes a 3D-printed holder that attaches the FUS transducer to the ultrasound phantom.

Acoustic coupling QA protocol

After the FUS system passed FUS device QA, the FUS transducer was mechanically positioned to align its focus at the planned target brain location, and an acoustic coupling procedure was conducted (Fig. 1c). QA for acoustic coupling was then performed with FUS sonication but without injecting microbubbles. For the acoustic coupling procedure, water inside the water bladder of the FUS transducer was degassed, the patient's hair above the tumor region was shaved, and degassed ultrasound gel was applied to the cleaned scalp. Bubbles trapped in the FUS probe water bladder and ultrasound gel could reflect the ultrasound wave and decrease the delivered acoustic energy in the brain. The purpose of acoustic coupling QA was mainly to assess whether air bubbles were trapped in the water bladder of FUS and ultrasound gel by detecting cavitation signals emitted by bubbles upon FUS sonication. Specifically, a custom Matlab script was written to perform a frequency transform of the acquired time-domain signals, and then a frequency range of 305–1320 kHz was chosen for the analysis. This frequency range was selected in reference to the bandwidth of the PAD sensor. For each patient study, the harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband signals over time were calculated by the root-mean-squared amplitudes of the second harmonic (2∗ ± 20 kHz), subharmonic (/2 ± 20 kHz), and broadband signal (excluding the frequency bandwidths of the second harmonic and subharmonic signals), respectively. The acoustic coupling QA was deemed failed if harmonic, subharmonic, or broadband signals were present in the detected signals when the FUS was turned on. These signals were considered present when the detected level exceeded the noise level by more than three standard deviations. In such a case, we would repeat the acoustic coupling procedure until no cavitations were detected.

FUS procedure QA protocol

PAD was used for the FUS procedure QA to detect the harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels in realtime during FUS sonication with microbubble injection. As the half-life of the microbubbles in the blood is only a few minutes after bolus injection,33 the kinetics of the microbubble cavitation activity show a pattern of fast increase followed by a decay to baseline.34 The FUS procedure was considered to pass the QA when this pattern was observed and vice versa. If the FUS procedure passed the QA, the PAD signals were quantified using the following metrics: onset of harmonic activity, the duration of harmonic activity, and harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband doses. The onset of the harmonic signal indicated the time when microbubbles reached the FUS focal region. It was determined by the time point that the harmonic level reached above the mean + three standard deviations of the harmonic baseline which was calculated based on the PCD signal acquired before microbubbles injection. The duration of the harmonic level reflected the lifetime of the injected microbubbles. It was defined by the duration that harmonic levels were above the mean + three standard deviations of the harmonic baseline. Harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband doses were computed by integrating the corresponding cavitation levels over time for each patient to quantify the overall cavitation activity.

Statistics

We included a total of ten patients (seven males and three females; average age 60 years; range 36–74 years) in this study. This sample size was considered sufficient for evaluating the QA procedure. All patients underwent the same QA procedure without randomization and blinding, as the procedure was needed for all studies. Data from all ten patients were included in the analysis. Statistics analysis of the data was performed in GraphPad Prism (Version 9.4, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are presented in the format of mean ± standard deviation. The dispersion of the data were also quantified using lower quartile (or first quartile, Q1, which is the value under which 25% of the data points are found when they are arranged in increasing order), upper quartile (or third quartile, Q3, which is the value under which 75% of data points are found when arranged in increasing order), median (or the second quartile, Q2), and interquartile range (IQR, which is the distance between Q1 and Q3).

Role of funders

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analyses, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the FUS device QA, acoustic coupling QA, and FUS-procedure QA results for ten patient studies. In this study, one case failed FUS device QA, one case failed acoustic coupling QA, and one case failed FUS procedure QA.

Table 2.

Summary of results from three QA procedures (NA: not applicable).

| Patient ID | FUS device QA | Acoustic coupling QA | FUS procedure QA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 01 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 02 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 03 | Fail | NA | NA |

| Patient 04 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 05 | Pass | Fail | NA |

| Patient 06 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 07 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 08 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

| Patient 09 | Pass | Pass | Fail |

| Patient 10 | Pass | Pass | Pass |

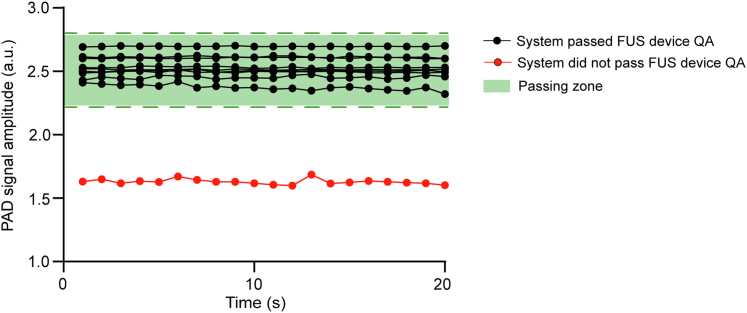

FUS device QA

Fig. 3 presents the FUS device QA results for the ten patient studies. Each line represents the amplitude of the detected PAD signals acquired before the FUS-BBBO procedure for each study, and the FUS device QA passing zone is indicated by the green shaded area. FUS device QA was passed in nine out of ten patient studies (Table 2). FUS device QA did not pass for Patient 03 due to the malfunction of the FUS transmitting system. The FUS output of Patient 03 was 8.2-fold lower than the other cases. In such a case, Patient 03 was excluded from this study.

Fig. 3.

FUS device QA results. The measured amplitude of the detected PAD signals as a function of time is displayed. The green-color shaded area marks the FUS device QA passing zone. Black dots indicate measurements from cases that passed the FUS device QA, and red dots show the case that failed the FUS device QA.

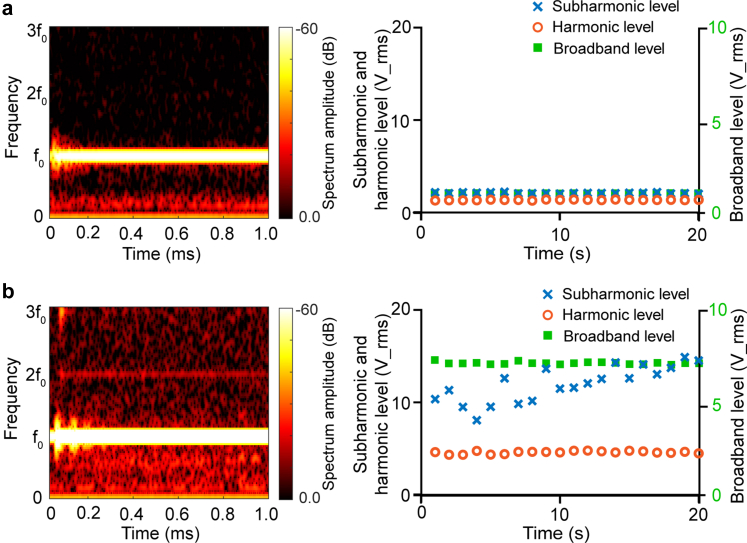

Acoustic coupling QA

In this study, four of nine cases failed acoustic coupling QA on the first attempt. The acoustic coupling procedure was repeatedly performed until it passed QA in three cases, with one case remaining failing the acoustic coupling QA (Patient 05). Fig. 4a shows a representative example of good acoustic coupling. As shown in the time-frequency analysis, the detected acoustic signal was primarily concentrated at with no obvious harmonic, sub-harmonic, or broadband signals. Fig. 4b displays the time-frequency analysis for that failed case. It shows the presence of high harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels. Examination of the coupling medium found that the water bladder of the FUS transducer was leaking, and air bubbles were visually observed to be trapped near the PAD sensor. Unfortunately, we were unable to fix the water leakage issue during the procedure due to time constraints.

Fig. 4.

Acoustic coupling QA results. (a) Example of passed acoustic coupling QA. (b) Example of failed acoustic coupling QA. Time-frequency analysis shows the spectrum amplitude at different frequencies (left). The plot of harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels as a function of time shows the bubble activities over time (right). High harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels indicate bubbles trapped in the coupling medium. The orange circle, blue cross, and green square symbolize the second harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels, respectively.

FUS procedure QA

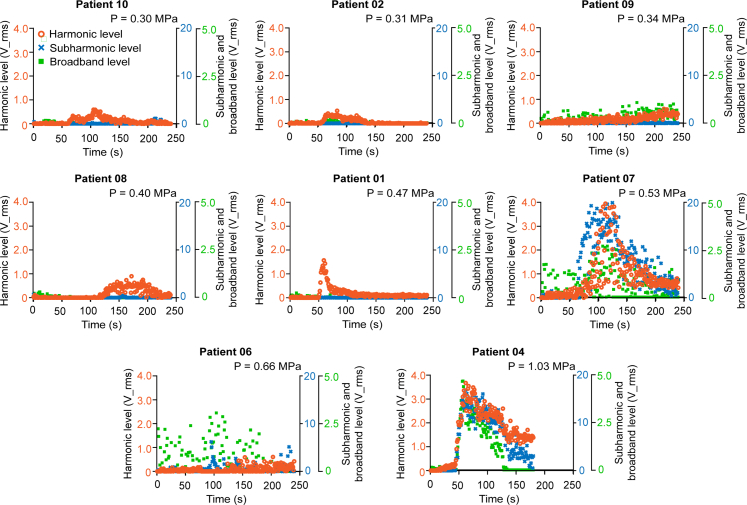

The harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels acquired from each patient during the FUS procedure are presented in Fig. 5. Patient 03 was excluded from this study because this case did not pass the FUS device QA. Patient 05 was excluded because the acoustic coupling QA failed. Patient 09 failed the FUS procedure QA because it did not show the trend of increase followed by a decrease in the harmonic level. Therefore, Patient 09 was excluded from the analysis of the onset of harmonic activity, duration of harmonic activity, and harmonic and subharmonic dose (Table 1). The onset time of the harmonic activity ranged from 27 s to 214 s, Q1 was 55.5 s, Q3 was 103 s, median was 62 s, and IQR was 47.5 s. The averaged harmonic duration ranged from 33 s to 189 s, Q1 was 85.5 s, Q3 was 158 s, median was 154 s, and IQR was 72.5 s. The average harmonic doses ranged from 1.81 to 28.9, Q1 was 2.56, Q3 was 12.3, median was 4.08, and IQR was 9.79. The average subharmonic dose ranged from 0.25 to 150.9, Q1 was 0.57, Q3 was 63.6, median was 1.38, and IQR was 63.0. The average broadband dose ranged from 0.95 to 185.2, Q1 was 2.30, Q3 was 106, median was 3.68, and IQR was 103.7. The variations were potentially from the inconsistent microbubble injection, as the injection was performed by different anesthesiologists. Regarding harmonic and subharmonic doses, strong harmonic activities were detected in two patients (Patients 04 and 07), with an averaged harmonic dose approximately 8.2-fold greater than the averaged harmonic dose of the other cases. This result was expected since those two cases applied relatively high acoustic pressure values compared to others. Subharmonic activities were also detected in these two patients (Patients 04 and 07). The average subharmonic dose of Patients 04 and 07 was approximately 50.8-fold greater than that of the other cases. For Patient 06, the anesthesiologist administered the microbubbles by injecting one-quarter of the microbubbles in about 5 s and pausing for 15 s and then injecting the remaining microbubbles for approximately 15 s.

Fig. 5.

FUS procedure QA results. Harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels as a function of time for eight patients. The data was ordered based on the in-situ pressure value. The cavitation levels varied between patients. The orange circle, blue cross, and green square symbolize the harmonic, subharmonic, and broadband levels, respectively.

Discussion

We developed a passive acoustic detection-based QA strategy with three specific functions: QA for the FUS device, QA for acoustic coupling, and QA for the FUS procedure. The proposed strategy offers an approach for FUS-induced BBB opening procedure QA in clinical applications.

The proposed FUS device QA phantom and procedure are innovative and easy to implement. It provided a convenient approach for checking the performance of the FUS device. The whole device QA procedure only took approximately 20 s. The passing zone was established based on prior repeated measurements of the device, providing a standard criterion for FUS device performance evaluation. The application of the FUS device QA can be extended to other transcranial FUS techniques, for example, FUS neuromodulation.

The proposed acoustic coupling QA provides a quantitative measure of the acoustic coupling quality. PAD was used in a previous non-human primate study to verify the coupling quality.13 In that study, Kamimura et al. used PAD to test acoustic coupling conditions by investigating stable cavitation and inertial cavitation doses acquired before microbubble injection to identify instances of inadequate acoustic coupling. Similar to their study, our results showed that improper coupling caused by bubbles trapped in the coupling medium was correlated with the presence of subharmonic and broadband emissions. Our study demonstrated, for the first time, that PAD could be a reliable tool for acoustic coupling QA in patients.

Although PAD is commonly used for FUS-BBBO procedure monitoring, previous studies only used harmonic and subharmonic levels/doses to evaluate the cavitation signals. We introduced the FUS procedure QA protocol, which included a criterion for FUS procedure pass/fail the QA and a set of metrics for evaluating the consistency of the procedure for those that passed the QA. One patient failed the FUS procedure QA as no clear harmonic signals were detected. We are unsure of the causes of this failed QA as we followed the same protocol for performing the FUS-BBBO procedure in all patients, highlighting the importance of FUS procedure QA. Variations in the onset and duration of cavitation signals were observed in both harmonic and subharmonic activities among different subjects. These variations were mainly caused by inconsistent microbubble injection, as the injection was performed by different anesthesiologists. Although the same instruction was given to anesthesiologists on duty, the implementation varied. For example, the eight patients' microbubble injection duration varied from 15 s to 133 s. To achieve consistent administration, it would be favorable if the attending anesthesiologist could have certain training before the procedure. Unfortunately, in our clinical study, anesthesiologists were rotated while on duty and the attending anesthesiologist for each case was not determined until the previous evening of the procedure day. It was not feasible to provide training on the microbubble injection to the attending anesthesiologist in our clinical workflow. This issue can be addressed in the future by performing microbubble injection with an automatic syringe pump or using a saline bag gravity drip.35 Variation in harmonic and subharmonic dose was observed, partly due to the difference in the in situ acoustic pressure (Table 1). We calculated the in situ acoustic pressure post-procedure based on the final trajectory used in the study. There are other potential confounding factors that could affect the measured cavitation dose. For example, factors like heart rate, vasculature density, and blood flow speed would affect the amount of microbubbles reaching the targeted brain region; factors like tumor tissue attenuation would affect the in situ acoustic pressure. In addition, it is noted that Patient 04 had relatively higher in situ pressure, which could be associated with a higher risk of tissue damage. Future studies are needed to integrate real-time cavitation monitoring-based feedback control algorithms to ensure consistent and safe FUS treatment. In summary, the FUS procedure QA could capture variations in the FUS procedure and provide a valuable tool to monitor and evaluate the consistency of the procedure. It is worth mentioning that the QA procedure proposed in this study is not exclusive. In the future, additional methods, such as monitoring the electrical power delivered to the FUS transducer,36 can be integrated to further enhance the QA process.

Currently, a range of ultrasound sensors are utilized for passive acoustic detection, yet there are no established standards for calibrating their sensitivity. Our proposed QA procedures are based on relative measurements compared to baselines, rather than absolute measurements. This method, which focuses on relative changes, effectively addresses the issue of varying sensitivities found in passive sensors across different devices. This approach allows our QA procedure to be implemented by other research groups using various devices. However, future research is required to develop standardized calibration methods for the sensitivity of the sensors. Such standards will enable the comparison of results obtained with different sensors.

The sensor used in this study has strengths and limitations. It was a small aperture planar transducer characterized by a diverging beam pattern, which allowed for a broad detection zone encompassing both the focal region and pre-focal region of the FUS transducer. It was sensitive in transcranial cavitation detection without requiring signal pre-amplification. However, the sensor shared the same center frequency as the FUS transducer, and it had a limited bandwidth of 260 kHz, characteristics determined by its manufacturing design. A sensor with a center frequency different from that of the FUS transducer would reduce the interference caused by FUS transmission. Moreover, a sensor with a broader bandwidth would capture signals with a wider range of frequencies. Future research should focus on developing PAD-specific sensors with extensive detection zones, high sensitivity, and wide frequency bands to enhance detection capabilities.

In conclusion, this study successfully developed a QA procedure for FUS-BBBO procedures. The QA procedure includes three functions: FUS device QA, acoustic coupling QA, and FUS procedure QA. The performance of the QA procedure was evaluated in 10 glioma patients, which demonstrated the clinical applicability of this procedure.

Contributors

CYC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Data Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing–Original Draft, Visualization; JYY: Methodology, Data Curation, Validation, Writing–Review & Editing; LX: Hardware, Data Curation, Data Validation, Writing–Review & Editing; SF: Data Curation; AS: Data Curation; UA: Data Curation, Writing–Review & Editing; EC: Data Curation, Writing–Review & Editing, Funding acquisition; HC: Conceptualization, Resources, Data Validation, Writing–Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available within the article. Raw data files will be made available by the authors upon request.

Declaration of interests

ECL and HC are inventors on an awarded US patent filed by Washington University in St. Louis on the sonobiopsy technique (US11667975B2), which covers the overall methods and systems for noninvasive and localized brain liquid biopsy using focused ultrasound. ECL and HC serve as advisors and shareholders of Cordance Medical, Inc., which is involved in commercializing the sonobiopsy technique. This relationship did not influence the design, execution, or interpretation of the study presented in this manuscript. The conflict of interest has been rigorously managed by Washington University in St. Louis. ECL received consulting fee from Neurolutions E15 and own stock from Neurolutions, Osteovantage, Face to Face Biometrics, Caeli Vascular, Acera, Sora Neuroscience, Inner Cosmos, Kinetrix, NeuroDev, Inflexion Vascular, Aurenar, Petal Surgical, which are not related to the present study. UA has K08 grant (K08NS125038) and Brain aneurysm foundation grant (GR0026849). This relationship did not influence the design, execution, or interpretation of the study presented in this manuscript. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01CA276174, R01MH116981, UG3MH126861, R01EB027223, R01EB030102, and R01NS128461.

Role of funding source: The funders played no part in the design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, writing of the report or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Gorick C.M., Breza V.R., Nowak K.M., et al. Applications of focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;191 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114583. Elsevier B.V. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H.L., Hua M.Y., Chen P.Y., et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption with focused ultrasound enhances delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs for glioblastoma treatment. Radiology. 2010;255(2):415–425. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leinenga G., Götz J. Scanning ultrasound removes amyloid-b and restores memory in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(278):1–12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee E.J., Fomenko A., Lozano A.M. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound: current status and future perspectives in thermal ablation and blood-brain barrier opening. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2019;62(1):10–26. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2018.0180. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpentier A., Canney M., Vignot A., et al. Clinical trial of blood-brain barrier disruption by pulsed ultrasound. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(343) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipsman N., Meng Y., Bethune A.J., et al. Blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu L., Cheng G., Ye D., et al. Focused ultrasound-enabled brain tumor liquid biopsy. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6553. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24516-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacia C.P., Zhu L., Yang Y., et al. Feasibility and safety of focused ultrasound-enabled liquid biopsy in the brain of a porcine model. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64440-3. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pacia C.P., Yuan J., Yue Y., et al. Sonobiopsy for minimally invasive, spatiotemporally-controlled, and sensitive detection of glioblastoma-derived circulating tumor DNA. Theranostics. 2022;27(1):362–378. doi: 10.7150/thno.65597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng Y., Pople C.B., Suppiah S., et al. MR-guided focused ultrasound liquid biopsy enriches circulating biomarkers in patients with brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(10):1789–1797. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iec . 2014. Technical specification ultrasonics-Field characterization-Specification and measurement of field parameters for high intensity therapeutic ultrasound (HITU) transducers and systems international electrotechnical commission XD. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iec . 2013. International standard norme internationale ultrasonics-power measurement-High intensity therapeutic ultrasound (HITU) transducers and systems Ultrasons-Mesurage de puissance-Transducteurs et systèmes ultrasonores thérapeutiques de haute intensité (HITU)https://webstore.iec.ch/publication/7196 [cited 2023 Dec 16]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S.H., Kim M.J., Jung H.H., et al. Safety and feasibility of multiple blood-brain barrier disruptions for the treatment of glioblastoma in patients undergoing standard adjuvant chemotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2021;134(2):475–483. doi: 10.3171/2019.10.JNS192206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen K.T., Chai W.Y., Lin Y.J., et al. Neuronavigation-guided focused ultrasound for transcranial blood-brain barrier opening and immunostimulation in brain tumors. Sci Adv. 2021;7(6) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd0772. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abd0772 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrahao A., Meng Y., Llinas M., et al. First-in-human trial of blood–brain barrier opening in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2019 Dec 1;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumprecht H.K., Widenka D.C., Lumenta C.B. BrainLab VectorVision neuronavigation system: technology and clinical experiences in 131 cases. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:97–105. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199901000-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynynen K., Pomeroy O., Smith D.N., et al. MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound surgery of fibroadenomas in the breast: a feasibility study. Radiology. 2001;219(1):176–185. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.1.r01ap02176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess M.T., Konofagou E.E. Fast qualitative two-dimensional mapping of ultrasound fields with acoustic cavitation-enhanced ultrasound imaging. J Acoust Soc Am. 2019;146(2):EL158–E164. doi: 10.1121/1.5122194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morchi L., Mariani A., Diodato A., Tognarelli S., Cafarelli A., Menciassi A. Acoustic coupling quantification in ultrasound-guided focused ultrasound surgery: simulation-based evaluation and experimental feasibility study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(12):3305–3316. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamimura H.A.S., Flament J., Valette J., et al. Feedback control of microbubble cavitation for ultrasound-mediated blood–brain barrier disruption in non-human primates under magnetic resonance guidance. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39(7):1191–1203. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17753514. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0271678X17753514 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prada F., Gennari A.G., Linville I.M., et al. Quantitative analysis of in-vivo microbubble distribution in the human brain. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91252-w. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song K.H., Harvey B.K., Borden M.A. State-of-the-art of microbubble-assisted blood-brain barrier disruption. Theranostics. 2018;8(16):4393–4408. doi: 10.7150/thno.26869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S.Y., Tung Y.S., Marquet F., et al. Transcranial cavitation detection in primates during blood-brain barrier opening-a performance assessment study. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2014;61(6):966–978. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2014.2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park T.Y., Pahk K.J., Kim H. Method to optimize the placement of a single-element transducer for transcranial focused ultrasound. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;179 doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.104982. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinton G., Aubry J.F., Bossy E., Muller M., Pernot M., Tanter M. Attenuation, scattering, and absorption of ultrasound in the skull bone. Med Phys. 2012;39(1):299–307. doi: 10.1118/1.3668316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gasca-Salas C., Fernández-Rodríguez B., Pineda-Pardo J.A., et al. Blood-brain barrier opening with focused ultrasound in Parkinson's disease dementia. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21022-9. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainprize T., Lipsman N., Huang Y., et al. Blood-brain barrier opening in primary brain tumors with non-invasive MR-guided focused ultrasound: a clinical safety and feasibility study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36340-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anastasiadis P., Gandhi D., Guo Y., et al. Localized blood–brain barrier opening in infiltrating gliomas with MRI-guided acoustic emissions–controlled focused ultrasound. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(37) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2103280118. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2103280118 Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu L., Pacia C.P., Gong Y., et al. Characterization of the targeting accuracy of a neuronavigation-guided transcranial FUS system in vitro, in vivo, and in silico. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2023;70(5):1528–1538. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2022.3221887. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9947216/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan J., Xu L., Chien C.Y., et al. First-in-human prospective trial of sonobiopsy in high-grade glioma patients using neuronavigation-guided focused ultrasound. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):92. doi: 10.1038/s41698-023-00448-y. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41698-023-00448-y Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadera S., Chukwu C., Stark A.H., et al. Focused ultrasound-mediated delivery of anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1 antibody to the brain of a porcine model. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(10) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15102479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noel R.L., Batts A.J., Ji R., et al. Natural aging and Alzheimer's disease pathology increase susceptibility to focused ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30466-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unger E.C., Porter T., Culp W., Labell R., Matsunaga T., Zutshi R. Therapeutic applications of lipid-coated microbubbles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56(9):1291–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarro-Becerra J.A., Song K.H., Martinez P., Borden M.A. Microbubble size and dose effects on pharmacokinetics. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(4):1686–1695. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y., Meng Y., Pople C.B., et al. Cavitation feedback control of focused ultrasound blood-brain barrier opening for drug delivery in patients with Parkinson's disease. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(12) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14122607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams C., McLaughlan J.R., Carpenter T.M., Freear S. HIFU power monitoring using combined instantaneous current and voltage measurement. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2020;67(2):239–247. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2019.2941185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]