Abstract

The sustainability of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain plays a crucial role in providing economic benefits, minimizing social and environmental impacts, and optimizing resource utilization. This research aims to analyze the sustainability performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain using multi-criteria assessment and formulate strategies for sustainability improvement. The study proposes a multi-criteria assessment model with twenty-eight indicators and four dimensions of sustainability: economic, social, environmental, and resources, which were developed based on previous research. The fuzzy inference system (FIS) and multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) methods were utilized to analyze the multi-criteria indicators of sustainability performance in each dimension and overall supply chain. The Adaptive Neuro Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) model was used to aggregate multi-dimension sustainability to achieve overall sustainability performance. A fuzzy cognitive map (FCM) framework was developed to formulate strategies for improving the sustainability performance of the supply chain. The research was verified at two sugar mill locations in Java Island, Indonesia. The FIS and MDS models successfully analyzed the sustainability performance of the two sugar agro-industries, showing an average value of “quite sustainable”. The overall sustainability performance using the ANFIS model for mill A and B were 57.2 and 61.9, respectively. Series of FGDs combined with the FCM model successfully formulated five clusters of strategies as initiatives in improving the sustainability performance, namely raw material provision, harvesting and post-harvest activities, production process optimization, IT-based technology implementation, and institutional aspects. This present work seeks to contributes to the development of multi-criteria of sustainability performance for the food industry's supply chain. It also proposes a comprehensive framework for analyzing and improving sustainable supply chain performance under uncertainty using a combination of conventional and fuzzy assessment modeling approach. A practical initiative strategy in sustainability improvement is revealed for the sugarcane agroindustry's supply chain.

Keywords: Agroindustry, Fuzzy modeling, Strategy improvement, Sugarcane, Supply chain, Sustainability

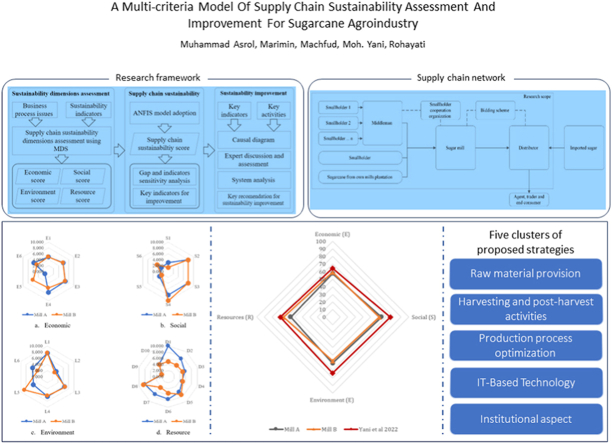

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Sugarcane supply chain assessment using multi-criteria model with 28 indicators.

-

•

Multi-dimensional scaling and neuro-FIS suggested for agroindustry's supply chain sustainability evaluation.

-

•

Supply chains sustainability performance are quite sustainable at two locations.

-

•

Fuzzy cognitive maps & focus groups identify sustainability improvement actions.

-

•

Five clusters of strategies proposed to boost sugarcane agroindustry's supply chain sustainability.

1. Introduction

The supply chain management has been widely utilized since the 1960s to enhance the efficiency and responsiveness of industries. It involves organizing stakeholders involved in the production process, from upstream to downstream, in order to provide added value to consumers and generate profits. Scholars and practitioners have identified numerous ways in which supply chain management contribute to enhancing business performance, engage stakeholders to achieve goals also enhancing customer loyalty. Moreover, in the present day, consumers are not only concerned about product price and quality but also the environmental impact of products and firms sustainability status [1] but also track the product traceability [2]. Therefore, there is a need to extend the scope and application of supply chain management to incorporate sustainability considerations, thus catering to the growing demand for environmentally-conscious supply chains.

Supply chain sustainability addresses a complex range of issues, including coordinating networks and ensuring the long-term viability of businesses while considering their impact on the environment and society. According to the definition that provided by Ref. [3] and strengthened by Ref. [4], supply chain sustainability managing multi-stakeholders in supply chain to coordinates the flow of materials, information, and finances in generating value for consumers, generate a profitable business for all stakeholders, and simultaneously produce positive social and economic advantages, reducing environment impacts and accelerating digital transformation. During this decade, the application of supply chain sustainability has significantly expanded across various sectors due to growing consumer expectations, regulatory pressures, and the desire to enhance business reputation. Moreover, it aligns with the goals of industry 4.0 initiatives, contributes to maintaining consumer trust and loyalty, satisfies consumer preferences, resource optimization, contributing to social and environment positive impact and sustainable production and consumption [5,6]. Until this part, it is crucial to incorporate sustainability considerations into supply chain practices, not only to mitigate environmental effects but also to foster corporate responsibility towards social and environmental concerns and meet consumer demands for natural products.

The implementation of supply chain sustainability encounters significant difficulties across various fields. These challenges arise from the complexity of managing stakeholders within the supply chain structure, which serves multiple purposes in sustainability applications. According to Tay et al. [7], these challenges do not only originate from internal stakeholders but also external factors such as regulators, technology, and competitors. Both internal and external barriers include issues related to human capital, finances, and a lack of awareness [8]. External factors further reveal a lack of government support and policies to facilitate the adoption of sustainability [9]. The adoption of sustainability practices in the supply chain requires a strategic approach that relies on data and information. However [3,10], identify challenges in terms of data and information availability, supply chain complexity, and stakeholder management when it comes to implementing sustainability in the supply chain. Firms in nowadays facing sustainability threats in its supply chain operations since the effect of uncertain demand and market challenging [11]. Another challenge faced by both scholars and practitioners is the absence of frameworks for adopting sustainable supply chain practices in specific industries [12].

Sustainability research has seen widespread application, with a focus on analyzing current sustainability performance. Supply chain sustainability assessment involves a systematic evaluation of the environmental, social, and economic impacts associated with a company's supply chain activities. This assessment is valuable for identifying areas of improvement, prioritizing sustainability initiatives, and monitoring progress over time. Research on sustainability should not only focus on the developed models or methods but also consider the appropriate dimensions and indicators to be included in the analysis and assessment. However, assessing supply chain sustainability poses challenges due to the uncertain, complex, and incomplete nature of information sources within the intricate business processes of the supply chain [13]. Fritz et al. [14] found 115 indicators in sustainability performance measurement, whereas Papilo et al. [15] proposed 11 indicators in sustainability analysis. To effectively assess supply chain sustainability, certain criteria and standards must be met, as we named as multi-criteria for assessing supply chain sustainability performance. These include addressing supply chain goals, defining appropriate dimensions and indicators, and ensuring that the assessment model aligns with field applications. Multi-criteria that organized by dimensions and indicators for evaluating supply chain sustainability can be derived from existing literature, field observations, and expert validations [16].

The approach for assessing the sustainability performance of supply chains has been extensively studied in previous research. Typically, research has focused on defining dimensions and indicators, developing models, determining sustainability performance, and providing simplified, impractical recommendations. Egilmez [17] Conducting a performance evaluation of a US food manufacturing company and identifying sensitive factors can be one of the solutions, Abdella [18] designing a sustainability performance measurement model and clustering industries based on the measurement results, León-Bravo [19] assessing the sustainability performance of a food supply chain and then mapping these indicators to their impact on performance. However, to the best of the author's knowledge, no research has integrated supply chain sustainability with a continuous improvement approach to manage performance effectively. Additionally, a strategy to enhance sustainability is necessary to address low performance in specific dimensions and indicators. This aligns with the findings of Yadav et al. [12], which highlight the lack of frameworks for adopting supply chain sustainability in certain industries.

Given the significant impact of supply chain sustainability on industry performance and competitive advantages and also many challenges revealed as aforementioned, it is crucial to develop comprehensive frameworks and conduct situation analyses to identify supply chain opportunities in adopting sustainable practices. These frameworks should be specific to the business conditions and potential improvement strategies. Additionally, conducting a situation and requirement analysis of the supply chain helps stakeholders proactively enhance their initiatives towards sustainability adoption, aiming to gain competitive advantages. Earlier studies have also demonstrated evidence that implementing sustainability practices can enhance a company's performance. However, there is a lack of clarity regarding the specific factors that should be taken into account when engaging in sustainability activities to improve overall performance [20]. To address this gap, the development of a supply chain sustainability performance framework becomes essential for effectively managing the current supply chain situation and proposing further improvements [21]. The motivation of this research stems from this limited evidence and further sustainability initiatives benefits.

This research proposes a multidimensional performance measurement of supply chain sustainability, encompassing economic, social, environmental, and resource dimensions. Previous research has formulated dimensions and indicators for performance measurement but has been limited to the 3P framework, as demonstrated in sustainable supply chains [22], corporate sustainability reports [14], complex agro-industrial systems [23], and sugar agro-industry [24]. This research aims to introduce a new dimension, the resources dimension, by considering resource constraints in agro-industrial systems in developing countries. While resource dimensions have been considered in prior research [25], this study places a stronger emphasis on resource accessibility, competencies, raw material quality, and technological development. These aspects are addressed based on expert recommendations and the significant resource challenges faced in developing countries.

This study proposes the Indonesian sugarcane agroindustry supply chain as a case for assessing and validating supply chain sustainability. The sugarcane agroindustry is chosen due to its significant environmental and social impacts throughout the sugar production process and along the supply chain operations. Various factors of multiple dimensions pose challenges to achieving supply chain sustainability in the sugarcane agroindustry. These factors include land suitability [26], labor efficiency and cultivation practices [27], environmental impact and profitability [28], waste management [29], and distribution systems and information flow within the supply chain [30]. By studying and addressing these factors, the aim is to improve the sustainability performance of the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain.

Considering the various conditions, as a gap proposed in this research, this study sees the need for a sustainability performance measurement framework for supply chains with a multi-criteria approach combined with a comprehensive formulation for improving sustainability performance in the supply chain. This aligns with [12], who have noted the absence of a framework for assessing and enhancing sustainability performance in the supply chain comprehensively. Therefore, to shed light on the aforementioned challenges, this research is guided by the following research question (RQ).

RQ1

How is the multi-criteria assessment approach established for measuring sustainability performance in real-world supply chains?

RQ2

How is the performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain under various conditions of uncertainty?

RQ3

How can sustainability performance improvement initiatives in supply chains be applied to real-world industries?

This research paper makes a valuable contribution by developing multiple criteria to assess the sustainability performance of the food industry's supply chain. A series of focus group discussions were conducted with experienced experts to ensure that the multi-dimensional approach can be applied to the sugar industry. Additionally, it presents a comprehensive framework to measure and improve the sustainability performance of the supply chain, applying multi-criteria approach, dealing with uncertain conditions, through the application of fuzzy assessment modeling. Furthermore, this study also provides decision recommendations for enhancing the sustainability performance of the sugar agro-industry supply chain by identifying relevant actors within the institutional system, based on the results of the multi-criteria assessment of sustainability supply chain performance.

The objective of this research is to evaluate the sustainability of the sugarcane supply chain and suggest strategies for improving sustainable business practices. A combined qualitative and quantitative approach is developed to assess the performance of supply chain sustainability while considering the uncertainties associated with data and information in the sugarcane supply chain. To design a practical strategy for enhancing supply chain sustainability, a fuzzy approach is employed, which incorporates expert discussions and validations.

This paper is organized into five sections: Introduction, Literature review, Methods, Results and Discussion, and Conclusion. The introduction provides an overview of the research topic's significance and objectives, highlighting the contribution to existing literature. Literature review provides three main issues, SSCM, sustainability assessment and related works to formulate research gap. The methods section explains the research design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. In the results and discussion, the findings of supply chain sustainability performance and its improvement initiatives are presented, analyzed, and compared with previous studies. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the key findings and their implications, suggesting potential areas for improvement and future research directions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Sustainable supply chain management

Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is the combination of two concepts, namely sustainability and supply chain management. The term sustainability, or sustainable, was introduced in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and Development [31] as “a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Sustainability has also been widely published in the Scopus database to this day, with various application areas [32]. Supply chain management has been known since the end of World War II, and its applications have grown rapidly in the 1960s alongside the industrial revolution. Referring to one reference, Ballou [33] defined supply chain management as integrated management that considers the contributions and functions of stakeholders to produce products. Chopra et al. [34] further complements the definition of supply chain management as a system that coordinates internal, external, and production systems to produce products or services by involving all stakeholders to meet consumer needs and generate profits.

The sustainability and supply chain management approaches are then integrated to achieve more precise business goals, driven by business competition, consumer preferences, also government and NGO mandates. Academics have defined sustainable supply chain as an integrative approach in balancing economic business achievements, social benefits, and environmental impact reduction. To complement this definition, Table 1 provides an overview of some definitions of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) in previous research by year.

Table 1.

SSCM definition in literature.

| No | Author | SSCM definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seuring and Müller [3] | Management of material, information, and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, economic, social and environmental. |

| 2 | Carter and Rogers [35] | The strategic, transparent integration and achievement of an organization's social, environmental, and economic goals in the systemic coordination of key interorganizational business processes for improving the long-term economic performance of the individual company and its supply chains. |

| 3 | Carter [36] | As a long run improvement of the organization in line with the triple bottom line approach and providing a bright planning to achieve business goals |

| 4 | Pagell and Shevchenko [37] | Designing, organizing, coordinating, and controlling of supply chains to become truly sustainable with the minimum expectation of a truly sustainable supply chain being to maintain economic viability, while doing no harm to social or environmental systems. |

| 5 | Brandenburg et al. [38] | The integration of environment, social and economic goals which is focused on forward supply chain and completed by closed loop system, remanufacturing and product recovery. |

| 6 | Giannakis and Papadopoulos [39] | “SSCM is considered as a sophisticated process by which firms organize their CSR (corporate social responsibility) activities across dislocated manufacturing processes spanning organizational and geographical boundaries." |

| 7 | Dubey et al. [40] | In line with the definition of SSCM by Ref. [3], however, extend the sustainability dimensions into 13 drivers including institutional pressure, product design, and technologies. |

| 8 | Formentini [41] | Management of product and service from the design phase to the different production stages starting with raw material extraction and ending with the delivery of the product/service to the end consumer and, eventually, the reuse, recycling, or disposal phase, depending on the product/service, industries, and business models of firms. |

| 9 | Sánchez-Flores et al. [42] | Preservation of balance that may exist between social responsibility, care for the environment and economic feasibility throughout the supply chain functions. |

| 10 | Tsai et al. [43] | The effort to integrate sustainable development into supply chain monitoring. |

| 11 | Seuring et al. [4] | Managing multi-stakeholders in supply chain to coordinates the flow of materials, information, and finances in generating value for consumers, generate a profitable business for all stakeholders, and simultaneously produce positive social and economic advantages, reducingenvironment impacts and accelerating digital transformation. |

| 12 | Abualigah et al. [44] | Ensuring the supply chain is operated in sustainable manner, does not harm environment and society, including all activities involving production and delivery. |

Various previous studies described in Table 1 agree that SSCM combines the sustainability and supply chain management approaches. Sustainable approach needs to consider all activities in the supply chain, coordinate stakeholders, and ensure that the processes are economically, socially, and environmentally viable. However, this process can start at the focal company, which plays a crucial role in governing the flow of supply chain management.

The literature also conveys that sustainability cannot focus on a single aspect but needs to consider it in a multi-dimensional manner. While conventional supply chains previously focused on the economic dimension, in SSCM, it generally considers the triple bottom line. Over time, the understanding of SSCM has also broadened, not just focusing specifically on one factor. These definitions highlight the supply chain as a key component for sustainable development, where environmental, social, and economic criteria must be satisfied.

2.2. Sustainability assessment

In the previous section, a conceptual definition of SSCM is explored, which encompasses all aspects within the supply chain that are considered in sustainable operations, as well as indicators or dimensions that are managed. An important part of SSCM is understanding the current state of the sustainable supply chain and formulating the next steps for improvement, which furthers is referred to the supply chain sustainability assessment. Several previous studies that addressed the issue of sustainability assessment can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sustainability assessment dimensions and model.

| No | Author | Object | Model | E | S | N | R | IT | L | O | G | C | F | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jaya et al. [45] | Coffee agroindustry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 2 | Jaya et al. [46] | Corn production |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 3 | Fahrizal et al. [47] | Sugarcane agroindustry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 4 | Peano et al. [23] | Agrifood |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 5 | Formentini and Taticchi [48] | Coffee industry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 6 | Sopadang et al. [24] | Sugarcane agroindustry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 7 | Kot [49] | SMEs supply chain |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 8 | Papilo et al. [50] | Biodiesel industry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 9 | Wiryawan et al. [51] | Fresh-cut vegetable |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 10 | Alahyari and Pilevari [52] | Automotive industry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 11 | Tuni et al. [53] | Multi-national manufacturing company |

|

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 12 | Mursidah et al. [54] | Sugarcane agroindustry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 13 | Asrol et al. [55] | Biodiesel industry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 14 | León-Bravo et al. [19] | Food supply chain |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 15 | Wan et al. [56] | Marine ranching |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 16 | León-Bravo et al. [57] | Fresh fruit and vegetable supply chain |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| 17 | Yani et al. [25] | Sugarcane agroindustry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 18 | Naghi Beiranvand et al. [58] | Oil and gas industry |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 19 | Ahmad [59] | Food manufacturing |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| 20 | Lestari et al. [60] | Palm oil mill |

|

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Total | 20 | 17 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

E: Economic, S: Social, N: Environment, R: Resources, F: Food safety, G: Governance, IT: Information technology, L: Logistic, O: Supply chain operation, C: Supply chain capability, F: Food safety, T: Technology.

In the past ten years, sustainability assessment has been discussed in various fields using a wide range of methods. The proposed models are quite diverse, including multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), multi-dimensional scaling (MDS), fuzzy modeling, and machine learning. The MCDM was applied in the first five years, and machine learning models have been applied in the last five years. Interestingly, MDS has been used throughout the past decade due to its advantages in assessing sustainability performance. MDS is not only applied to sustainability performance assessment in the supply chain field but also in various research areas that focus on sustainability performance evaluation.

The MDS method is a statistical approach that groups objects based on the similarity of specific variables [50]. It also applied to assess the performance of sustainability dimensions through the values of indicators within those dimensions. MDS is a multi-variable measurement approach that is suitable for the conditions of sustainability assessment. MDS also has advantages compared to other multi-variable measurement models, as revealed in Fauzi and Ana [61].

In previous research, researchers considered various dimensions in measuring sustainability performance. However, the majority of researchers agree to maintaining economic, social, and environmental dimensions, except in studies by Refs. [51,53,57] which were employed additional criteria. Dimension and indicator to adopting sustainability assessment must consider the specific condition of the study object. The literatures revealed that researchers are no longer rigidly confined to the three traditional dimensions in sustainability performance measurement but have expanded into other dimensions, such as resources [45,47,57,58], supply chain operation [46,51,57,58] and supply chain capability [56,57].

2.3. Related works and contributions

Managing supply chain sustainability must consider many components including criteria, methods, and improvement strategies. This study proposes agroindustry case which full of uncertainty variables that must be considered in sustainability analysis and improvement strategy. In sustainability analysis requires identification of the most important components of environmental and social impact. Further approach, action in sustainability improvement must be define for each related stakeholders [49].

Considering the complexity of agroindustry supply chain, the sustainability assessment must be started from its assessment criteria. Further, we called it multi-criteria since it involves four dimensions and 28 indicators. The multi-criteria approach must consider various conditions of data uncertainty in the field. Diverse data conditions, which come in various forms and units, should then be accommodated through a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Both data modes should be integrated into the model, as also suggested by Refs. [14,22,25]. The complexity will further increase with the effective accommodation of both data modes, but it aligns with real-world conditions.

Research related to supply chain sustainability assessment has been widely discussed in literature. Scholars have provided some methodological approaches in sustainability assessment, including multi-criteria decision making, fuzzy modeling approaches, multi-dimensional scaling and machine learning modeling. However, previous studies have offered limited approaches for enhancing sustainability performance, mostly focusing on calculating sustainability performance using methods.

Some studies that have proposed methods for improving sustainability performance following performance evaluation include: Yani et al. [25], who introduce the cosine amplitude method for formulating supply chain performance; Papilo et al. [50], who analyze key indicators using leverage analysis; Souza and Alves [62], who develop a lean integrated framework for sustainability improvement; and other studies that utilize multi-criteria decision-making techniques to formulate strategies for enhancing performance, such as revealed in Refs. [51,[63], [64], [65]].

Certainly, this research contributes to providing comprehensive framework to assess the supply chain sustainability and proposes key activities to improve performance while considering variables of uncertainty and scope. This research also contributes to provide multi-criteria assessment using a comprehensive four dimensions with 28 indicators to be applied in supply chain sustainability assessment accommodating qualitative and quantitative approach. The study suggests the use of multidimensional scaling to evaluate supply chain sustainability and fuzzy cognitive maps to formulate strategies for enhancing sustainability performance in uncertain environments.

3. Method

3.1. Research framework and flow

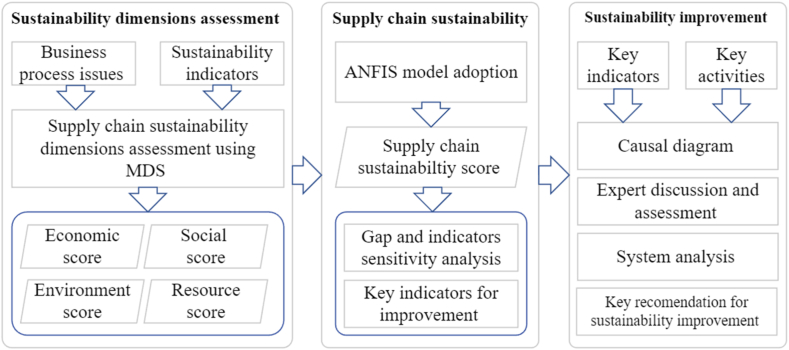

Fig. 1 presents the research framework, which consists of three main parts: sustainability assessment in multi-dimension performance, overall supply chain assessment aggregation and analysis, and formulation of key activities for improving sustainability performance. In the first stage, the sustainability with multi-criteria assessment organized by relevant dimensions and indicators are formulated. Expert opinions are gathered through focus group discussions to provide detailed insights into the sustainability dimensions, indicators, benchmarks, data sources, and their impacts on the supply chain process. The identified dimensions and corresponding indicators datasets are then collected from the field to assess the current sustainability performance of the supply chain.

Fig. 1.

Research framework.

At the second stage, to assess the multi-criteria performance of supply chain sustainability across its various dimensions, a combination of fuzzy inference system (FIS) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) approach is proposed. This analysis helps in determining the sustainability performance scores for each dimension. In this context, the supply chain sustainability score is established by considering multiple performance indicators, both qualitative and quantitative data. Additionally, the performance of multiple dimensions in supply chain sustainability is aggregated to provide an overall evaluation of the supply chain's performance using adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS).

During the third stage, the research focuses on proposing sustainability improvements to address any low performance in dimensions and indicators. This involves conducting multiple rounds of focus group discussions (FGDs) to identify problems, formulate key activities through comprehensive cause-effect analysis, and provide recommendations. The FGDs involve experienced experts from academia, business, community, and government sectors, which enhances the analysis and facilitates the establishment of action rules for improving sugarcane sustainability.

3.2. Data analysis and modeling

According to the research framework, this study comprises multi-model to assess the supply chain sustainability performance and formulate sustainability improvement initiatives. To explain the relationship between models, input and output of the study, the research flow is provided in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Research flow and relationship between models.

There are eight stages to answer the research questions including sustainability dimensions and indicators identification, sustainability performance analysis, and sustainability improvement initiatives. To accomplish these stages, the combination of multiple methods is required, including data normalization and multi-dimensional scaling, adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system, and fuzzy cognitive maps. Besides that, this study also required multi-techniques for data collection, including multi-series focus group discussions, interviews, and literature review. As far as the author's knowledge, there are not any previous research that combine all stage from the dimensions and indicator identification, sustainability assessment and improvement strategies to combine in a comprehensive study as proposed in this research. Most of the previous research reviewed sustainability dimensions and indicators and analyzed the sustainability performance, as it found in the most research provided in Table 2.

The research output/input for each stage is also provided in the research flow. It also explains the relationship between models for sustainability performance analysis and formulates sustainable supply chain operations. Since the analysis must be completed serially, therefore, an output of a model is required for the input in the next stage model. The detail method/model for sustainable supply chain performance analysis and improvement strategy is explained as follows.

3.2.1. Supply chain sustainability with multi-criteria assessment

To assess sustainability, it is crucial to define multi-criteria assessment with dimensions and indicators that effectively describe the performance. In our previous research [25] already defined multi-dimensions and indicators for supply chain sustainability for the sugarcane agroindustry. However, to adapt to the current industry conditions, it is necessary to re-validate these dimensions and indicators. For this purpose, a series of focus group discussions (FGDs) involving practitioners, academics, community members, and government representatives has been conducted.

These FGDs provide valuable insights and perspectives, ensuring that the dimensions and indicators are relevant and accurate for assessing supply chain sustainability in the present context. The dimensions and indicators that have undergone expert validation through the FGD process and are proposed in this study are provided at Table 3.

Table 3.

Sustainability dimensions and indicators.

| No | D | Indicators | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Economic | Supply chain risk (E1) | The risk level for all supply chain operations is evaluated by experts using the fuzzy linguistic labels |

| 2 | Sugar production loss (E2)a | The number of potential losses arising from the transformation of sugarcane into sugar. This indicator is calculated by fuzzy inference system using 4 input variable inputs: (1) blotong, (2) bagasse, (2) molasses and (4) potential sugar content loss. | |

| 3 | Fair Profit allocation among stakeholders (E3) | The analysis examines the distribution of profits among stakeholders based on their respective value-added contributions in the production process. This analysis utilizes a previous research scheme proposed by Ref. [66] to ensure a fair allocation of profits. | |

| 4 | Sugarcane price benchmark for farmer (E4) | The actual buying price for farmers' sugarcane, set by mills or middlemen, is compared to the reference price established by the government. This comparison helps assess whether the buying price aligns with the government's recommended price for sugarcane. | |

| 5 | Supply chain Agility (E5) | The ability to meet customer demand in a timely manner and with sufficient capacity. | |

| 6 | Return on investment (E6) | The total sales required to achieve investment goals refers to the level of revenue that needs to be generated to meet the desired return or profit relative to the initial investment. | |

| 7 | Social | Institutional support (S1) | Experts evaluate the institutional facilities and support systems that are responsible for managing and enhancing supply chain performance and sustainability. A fuzzy linguistic label is conducted to assess the indicators. |

| 8 | Supply chain infrastructure support (S2) | the availability and condition of physical infrastructure necessary for supporting supply chain processes and operations. This includes facilities, transportation networks and mode, road condition, and other related infrastructure elements. | |

| 9 | Corporate social responsibility (S3) | The corporate social responsibility impact to communities that are assessed by the stakeholders and experts using fuzzy linguistic labels. | |

| 10 | Waste complaints (S4) | The number of complaints initiated by communities or other stakeholders related to waste that produced by supply chain stakeholders: plantation and mills. | |

| 11 | Local labor employability (S5) | The quantity of local individuals engaged in supply chain operations and production activities. | |

| 12 | Stakeholder partnership (S6) | The count of smallholder sugarcane farmers participating in the partnership program with the mill and supplying their sugarcane to the mill. | |

| 13 | Environmental | Odor and dust disruption (N1) | The extent of disruption caused by mill odor and dust to the communities residing near the agroindustry and supply chain activities. |

| 14 | CO2 emission (N2) | The quantity of electricity generated through the production of sugarcane. | |

| 15 | Noisy level (N3)a | determined by assessing the workplace and open space noise within the mill. This indicator score is generated by FIS model with two variable inputs: (1) workplace noise level and (2) open space noise level. | |

| 16 | Water quality (N4)a | The water quality after undergoing wastewater treatment processes and being discharged into the surrounding environment. This quality is calculated using a Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) model with four sub-indicators: (1) total suspended solid, (2) biological oxygen demand, (3) chemical oxygen demand, and (4) sulfide. | |

| 17 | Ambient air quality (N5)a | The air quality surrounding the agroindustry as an impact of supply chain activities on the local community. This indicator is calculated using a Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) model with four sub-indicators (1) sulfur dioxide, (2) carbon monoxide, (3) nitrogen dioxide, and (4) dust. | |

| 18 | Solid waste (N6) | The quantity of solid waste generated during the sugar production process. | |

| 19 | Resources | Resource accessibility (R1) | The degree of accessibility to labor resources and supporting materials that facilitate the production process. |

| 20 | Level of sugarcane area conversion (R2) | The extent of land conversion from sugarcane areas to other functions or land uses. | |

| 21 | Labor competency (R3)a | The level of labor competency required to complete work orders efficiently and effectively. | |

| 22 | Raw material quality (R4)a | Evaluates the performance of sugarcane quality, as the main raw materials. This indicator is calculated using two sub-indicators: sugarcane productivity and sugar content. | |

| 23 | Overall recovery (R5)a | Assessed by boiling house recovery and mill extraction | |

| 24 | Raw material availability (R6) | The availability of raw materials meets both the mill's capacity requirements and customer demand. | |

| 25 | Ratoon level (R7) | The level of sugarcane ratoon, with level 3 being considered the optimal level. | |

| 26 | Responsive sugarcane variety availability (R8) | The availability of sugarcane varieties that can support the production of high-quality sugarcane under various land conditions and throughout different seasons. | |

| 27 | The availability of machinery and tools cultivation (R9) | The availability of machinery and tools that support cultivation activities and contribute to improving both the sugar content and productivity of sugarcane. | |

| 28 | Raw sugar technology (R10) | The availability of raw sugar technology refers to the presence of appropriate technology and processes required for receiving raw sugar materials and meeting the capacity of the sugar mill. This technology ensures efficient handling and processing of raw sugar materials to fulfill the operational requirements and production capacity of the mill. |

Generated using FIS model.

The multi-criteria model for supply chain sustainability assessment is organized by four dimensions with 28 different indicators, which differs from the previous study that only had 24 indicators. Indicators modification is adopted in the definition to facilitate data acquisition, and additional indicators have been included in the resource dimension due to their significant impact on the performance of the sugarcane agroindustry in Indonesia. Furthermore, there are several sub-indicators within certain indicators that will be aggregated using fuzzy inference system (FIS) to obtain indicator values, as also described in Table 3.

3.2.2. Supply chain sustainability performance analysis

A multi-dimensional (MDS) scaling is proposed to perform supply chain sustainability analysis. MDS is firstly proposed by Pitcher and Preikshot [67] to analyze the sustainability status of fisheries. MDS has several advantages to analyze the sustainability performance, including simply and comprehensive approach, enable to perform non-metric data, multi-dimensional measurement is possible to projected in the simple model, and the ability to processing both qualitative and quantitative data, which is in line with the multi-criteria assessment approach. MDS has a simplicity approach in managing sustainability analysis in many cases as it has been explored in section 2.

We proposed the following five stages to perform the sustainability analysis of each dimensions: First, the sustainability multi-criteria dimensions and indicators should be determined which were adopted from our previous research [25]. As aforementioned, we proposed some modification to the indicators, especially in resources dimension since it affects the supply chain sustainability with the high impact. The indicators are formulated through focus group discussion involving experts and stakeholders. The proposed indicators are qualitative and quantitative, and the data are collected in various ways. Besides that, positive and negative value of the indicators are also possible since there are many perspectives in assessment.

Second, a normalization technique is performed to accommodate the qualitative and quantitative data with positive and negative impact to performance. Suppose that is actual performance of indicator, and as lower and upper range of indicator c, and as target performance of indicator c with respect to and , then normalization score ) for lower and upper target are provided at Equations (1), (2)), respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Third, some indicators are generated using FIS model, including: sugar production loss (E2), noisy level (N3), water quality (N4), ambient air quality (N5), labor competency (R3), raw material quality (R4) and overall recovery (R5). The FIS model is generated using specific indicators and variable inputs, adopted from our previous research [25]. Fuzzy Inference System (FIS), with its advantages, enables easy and quick analysis and calculations on qualitative and quantitative data after data normalization. FIS can effectively handle both qualitative and quantitative data which is mostly found in agro-industry case. Using FIS in sustainability analysis is an opportunities for academician and practitioners contributes to formulate rules determining sustainability indicator score [68].

Fourth, once all the indicators have been addressed and data collection is finished, a Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) technique is utilized for sustainability analysis. The MDS model is applied through the following stages.

-

1.

Calculate the MDS ordination using the Euclidean distance (d) according to Equation (3).

| (3) |

-

2.

The Euclidean distance value is then approximated using regression (dij) as formulated in Equation (4).

| (4) |

-

3.

Sensitivity analysis is conducted to assess leverage and uncertainty using the Monte Carlo method. Leverage analysis aims to identify the impact of each indicator on sustainability performance, which is calculated using the root mean square error.

In the last stages, the dimensions score of sustainability performance generated by MDS is then aggregated to overall supply chain sustainability performance. As a comparison, in previous studies, a single score representing the multidimensional nature was obtained using approaches such as Monte Carlo simulations or expert-based weighting [50,51]. In this study, an adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) approach is utilized, which has been developed in prior research [25]. This model has been developed in our previous research, with a valid and appropriate testing, and has been proven capable of aggregating the performance of sustainable supply chains. The model consists of four dimensions as input, and the overall supply chain sustainability performance is the output.

3.2.3. Supply chain sustainability improvement

Sustainability improvement initiatives in supply chain performance is formulated using fuzzy cognitive maps (FCM). FCM was initially proposed by Ref. [69] to address social issues and decision-making problems. In its development, Hanafizadeh and Aliehyaei [70] further enhanced the FCM algorithm to generate decision recommendations. The capability of FCM has been proven in generating recommendations for complex systems. The FCM approach is also effective in providing accurate information based on the current system conditions [71]. FCM has demonstrated its ability to learn the interplay of factors within the system and assess their impact on goals or other factors [72]. Within this ability, this study proposes FCM to modeling the sugarcane supply chain system with causal-loop diagram to learn the system and provide the recommendations in improving sustainability.

The utilization of FCM for formulating initiatives to enhance supply chain sustainability begins with the development of activities and a causal diagram. The causal diagram identifies key activities that contribute to the achievement of the goal, which is the improvement of supply chain sustainability performance. Key activities are obtained through indirect activities (Ir (Ak, Ao)) and causal relationships (T). The scores of indirect activities in obtaining key activities are determined by the causal effects between key activities (Ak) and the goal activity (Ao) for all activity (i, kn, …, kn+1, j), as provided at Equation (5) and 6. The assessment of the relationships between activities in the causal diagram is provided by experts using Fuzzy scales, as shown in Equations (7)–(15).

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

3.3. Data collection

This research analyzes the multi-criteria sustainability performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain in two sugar mill locations at Java Island, Indonesia. These locations were selected as major sugar production centers that rely on sugarcane from small-scale farmers and face high risks [66]. The research collected both primary and secondary data, each obtained using specific techniques. Primary data refers to data collected directly from the source, while secondary data was collected from reports, documents, literature, or other secondary sources.

Primary data was collected using several techniques, including field observations, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. Field observations were conducted at the stakeholders of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain in the two locations, mill A and B. Field observations were necessary to directly observe the business conditions and confirm activities on-site. In-depth interviews were conducted to confirm and directly obtain responses related to sustainability issues from relevant informants. In-depth interviews involved preparing questions related to the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain business processes for sugarcane industry practitioners and community members in the surrounding area.

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted to gather the opinions and thoughts of experts regarding the indicators of sustainability in the sugarcane agro-industry and the formulation of performance improvement strategies. The FGD sessions in this research were conducted through several series to achieve the research objectives, which can be fully observed in Table 4.

Table 4.

FGD and respondents.

| FGD series | Goal | Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The formulation of sustainability assessment system, dimension, and indicators for supply chain agroindustry |

|

| 2 | Dissemination of sugarcane supply chain sustainability assessment toward key indicators for improvement |

|

| 3 | Formulation of key indicators and strategy for sugarcane supply chain sustainability improvement |

|

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Sugarcane supply chain business process

The business processes in the sugarcane agroindustry in Indonesia have their own characteristics that depend on the management of the industry. However, in general, the management of the sugar industry in Indonesia divided into private sugar mills and state-owned sugar mills. The management of the sugarcane agroindustry business begins with on-farm activities and ends with sugar packaging process. In the subsequent processes, such as selling to consumers through auction schemes, the authority is held by other companies. Therefore, in this study, the scope is limited to off-farm activities until obtaining the sugar product.

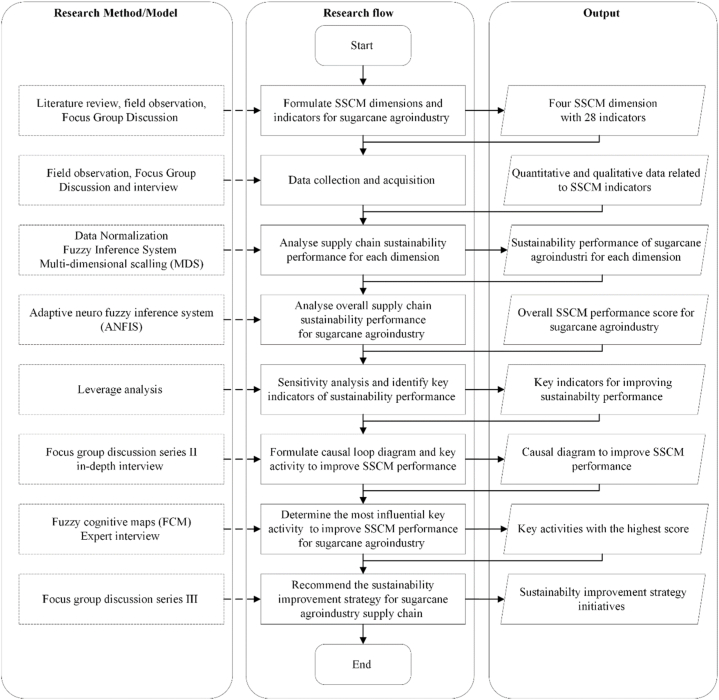

The business processes in the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain in Indonesia are categorized into several groups, including upstream, midstream, and downstream. In a previous study by Ref. [25], stakeholders in the sugarcane agroindustry were successfully identified, including farmers, sugar mills, and distributors. Fig. 3 provides a comprehensive representation of the stakeholders involved in the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain.

Fig. 3.

Sugarcane supply chain network.

Refer to supply chain network that the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain, from upstream to downstream to consumers, involves various stakeholders with different interests. Although this study is limited to on-farm and off-farm activities in sugar production, these activities also have a significant impact on the overall sustainability of the sugarcane agroindustry in providing products for consumers.

The sugarcane agroindustry in Indonesia has been a major driver of the economy, with the main production areas located on the island of Java. The sugarcane agroindustry currently faces various issues, primarily related to sustainability. Sustainability issues can be observed from various multi-criteria, but quantitatively, the sustainability of the sugar industry in Indonesia is concerning. Quantitatively, sustainability issues can be directly seen from the production volume, potential production losses, and the number of operational sugar mills in recent years.

Fig. 4 and Table 5 illustrate the statistics of Indonesian sugar mills. The sugarcane owned by farmers is the main supplier for government-owned sugar industry in Indonesia. Over the past ten years, there has been a downward trend in both the production volume and the cultivated area of sugarcane. This general trend can directly impact the sustainability of the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain, as the availability of raw materials becomes threatened. Furthermore, when examining the performance of the sugar mills, it can be observed that inefficiencies exist in several indicators. These inefficiencies lead to a decrease in farmers' trust in the mills, an increase in production costs, and the possibility of structured losses.

Fig. 4.

Sugarcane production and area by smallholder. [73]

Table 5.

Indonesian mill performance.

| Indicator | Units | World | India | Indonesia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugarcane productivity | Ton/Ha | 80–90 | 70–85 | 50–75.7 |

| Sugar content | % | 12–14 | 10–11 | 5.8–8.0 |

| Steam consumption | % cane | <40 | 42–45 | 52–60 |

| Power consumption | Kwh/TCD | 25 | 30 | 35 |

| Blackout time | % | <2.5 | <2.5 | >2.5 |

| Overall recovery | % | 85–87.5 | 85–87 | 70–79 |

4.2. Supply chain sustainability analysis

4.2.1. Multi-indicator for sustainability assessment framework

As previously mentioned, the sustainability of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain was analyzed using a multi criteria and multi-methodology approach involving f uzzy inference system, multi-dimensional scaling (MDS), and adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS). Four dimensions of sustainability were proposed to assess the level of sustainability in the sugarcane agro-industry, namely economic, social, environmental, and resource. Previously, the sustainability analysis of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain had also been evaluated using these dimensions through the FIS approach [25]. This study represents a development of the sustainability assessment model, focusing on adjusting the indicators within each sustainability dimension. The validation of the dimensions and indicators of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain sustainability has been adjusted to reflect the actual conditions in the field.

The use of Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) with a larger number of input variables can encounter the curse of dimensionality and it must generate too many rules that deliver to inefficient process [77]. This may pose a challenge, particularly in dimensions that have a high number of indicators. Considering the inefficiency of FIS in assessing the sustainability level of dimensions in the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain, the multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) model is proposed as an alternative approach.

The assessment of sustainability in the sugarcane agroindustry supply chain is based on the sustainability scores of each dimension and ultimately the overall sustainability score. In this study, four dimensions are proposed: economic, social, environmental, and resource. In a previous study [25], these four dimensions were also suggested, with each dimension consisting of six indicators. In this study, to enrich the analysis all indicators from previous study have been validated through focus group discussions with experienced experts. Furthermore, data collection was conducted for the indicators, which were then normalized using relevant benchmarks. Performance comparisons were also conducted between two sugar industries in Indonesia. Table 6 presents the sustainability performance indicators, benchmarks, and field-collected data.

Table 6.

Indicators for assessing sugarcane agroindustry supply chain sustainability.

| No | Indicators | Benchmark |

T |

Z |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| u | U | Mill A | Mill B | |||

| E1 | Supply chain risk | Very low | Very high | Very low | High | High |

| E2 | Sugar production loss | |||||

| E2.1. Pol blotong | 0.000 | 2.600 | 0.000 | 2.400 | 2.030 | |

| E2.2. Pol ampas | 0.000 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 1.350 | 1.290 | |

| E2.3. Pol tetes | 0.000 | 30.000 | 0.000 | 29.400 | 28.830 | |

| E2.4. Sugar content loss (%) | 0.000 | 0.640 | 0.000 | 0.490 | 0.490 | |

| E3 | Fair Profit allocation among stakeholders (%) | 15.000 | 30.000 | 15.000 | 20.000 | 20.000 |

| E4 | Sugarcane price benchmark for farmer (IDR) | 0.000 | 6.870 | 0.000 | 2.000 | 3.000 |

| E5 | Supply chain Agility (%) | 0.000 | 25.000 | 25.000 | 3.448 | 15.000 |

| E6 | Return on Investment (%) | 0.000 | 50.000 | 50.000 | 29.000 | 22.560 |

| S1 | Institutional support | Very low | Very high | Very high | Very low | Very low |

| S2 | Supply chain infrastructure support | Worst | Excellent | Excellent | Good | Excellent |

| S3 | Corporate social responsibility | Worst | Excellent | Excellent | Good | Good |

| S4 | Waste complaints | Very rare | Very frequent | Very rare | Rare | Very rare |

| S5 | Local labor employability (%) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 34.190 | 25.862 |

| S6 | Stakeholder partnership (%) | 0 | 15 | 15 | 4.000 | 6.572 |

| L1 | Odor and dust disruption | Very low | Very high | Very low | Low | low |

| L2 | Emission (/Ton) | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.000 | 0.156 | 0.171 |

| L3 | Noisy level | |||||

| L3.1 Workspace noisy level (db) | 50.000 | 85.000 | 50.000 | 56.00 | 52.40 | |

| L3.2 Open space noisy level (db) | 40.000 | 80.000 | 40.000 | 59.00 | 55.70 | |

| L4 | Water quality | |||||

| L4.1. TSS (mg/L) | 0.000 | 25.000 | 0.000 | 5.00 | 42.70 | |

| L4.2. BOD5 (mg/L) | 0.000 | 60.000 | 0.000 | 3.52 | 47.20 | |

| L4.3. COD (mg/L) | 0.000 | 150.000 | 0.000 | 26.12 | 94.80 | |

| L4.4. Sulfide (mg/L) | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |

| L5 | Ambient air quality | 0.000 | 262.000 | 0.000 | 15.20 | 7.60 |

| L5.1. Sulfur dioxide (μg/Nm3) | 0.000 | 10000.000 | 0.000 | 1955.00 | 2300.00 | |

| L5.2. carbon monoxide (μg/Nm3) | 0.000 | 92.500 | 0.000 | 70.40 | 7.90 | |

| L5.3. Nitrogen dioxide (μg/m3) | 0.000 | 230.000 | 0.000 | 216.00 | 72.50 | |

| L5.3. Dust (μg/Nm3) | 0.0067 | 0.8 | 0.0067 | 0.36 | 0.50 | |

| L6 | Solid waste emision | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.000 | 0.156 | 0.171 |

| R1 | Resource accessibility | Very low | Very high | Very high | Very high | Moderate |

| R2 | Level of sugarcane area conversion (%) | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4.28 | 8.046 |

| R3 | Labor competency | |||||

| R3.1. Productivity (%) | 50 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 80 | |

| R3.2. Training hours (%) | 0 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 4.465 | 4.465 | |

| R4 | Raw material quality | |||||

| R4.1. Productivity (Ton/Ha) | 55 | 88 | 88 | 88.06 | 88.06 | |

| R4.2. Sugar content (%) | 6 | 10 | 10 | 7.3 | 7.3 | |

| R4.3. Sweet, clean, and fresh quality. | Very low | Very high | Very high | High | Moderate | |

| R5 | Overall recovery (%) | 75 | 85 | 85 | 81.15 | 82.22 |

| R6 | Raw material availability (%) | 80 | 95 | 95 | 91 | 88 |

| R7 | Ratoon level | 3 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| R8 | Responsive sugarcane variety availability | 0 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 85 |

| R9 | The availability of machinery and tools cultivation | Very low | Very high | Very high | Low | Low |

| R10 | Raw sugar technology adoption | Very low | Very high | Very high | Moderate | Moderate |

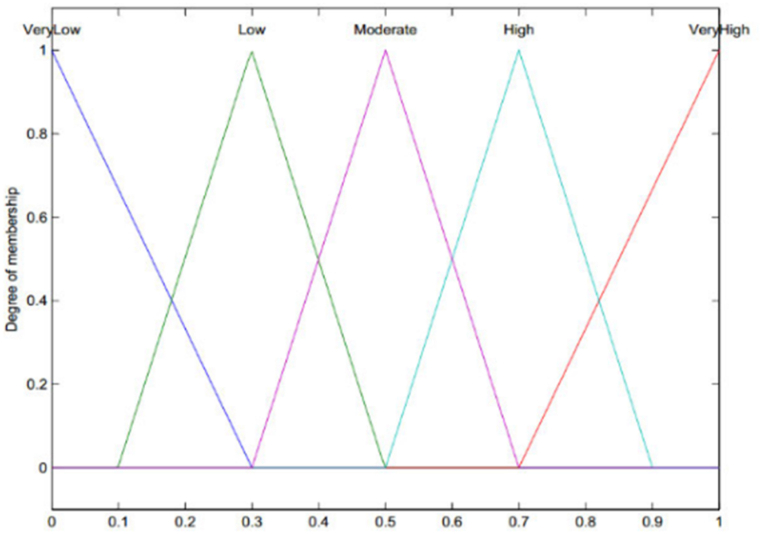

It can be observed that the model employed multi-criteria with 28 indicators for assessing the performance of the sustainable supply chain in the sugarcane agro-industry. Four indicators are added for resource dimension (R) expanded from previous research. These indicators are assessed both qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative assessment is conducted through expert interviews using fuzzy linguistic scales, which can be seen in Fig. 5. Quantitative assessment begins with secondary data collection in the field, which is then analyzed using appropriate formulas as described in detail in Ref. [25]. Additionally, quantitative assessment also requires inference to obtain a comprehensive value, which in this case involves the use of a fuzzy inference system model.

Fig. 5.

Fuzzy linguistic label for qualitative supply chain sustainability indicators.

Six fuzzy inference system (FIS) models are developed to analyze the sustainability indicator values of the supply chain. These models are: potential production loss (E2), noise level (L3), water quality (L4), ambient air quality (L5), workforce competence (R3), and raw material quality (R4). In general, the framework of the FIS model is depicted in Fig. 6, which includes the processes of data collection, indicators, data normalization, MDS model, ANFIS, and the overall sustainability value of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain.

Fig. 6.

Overall model framework.

4.2.2. Sustainability analysis using multi-dimensional scaling (MDS)

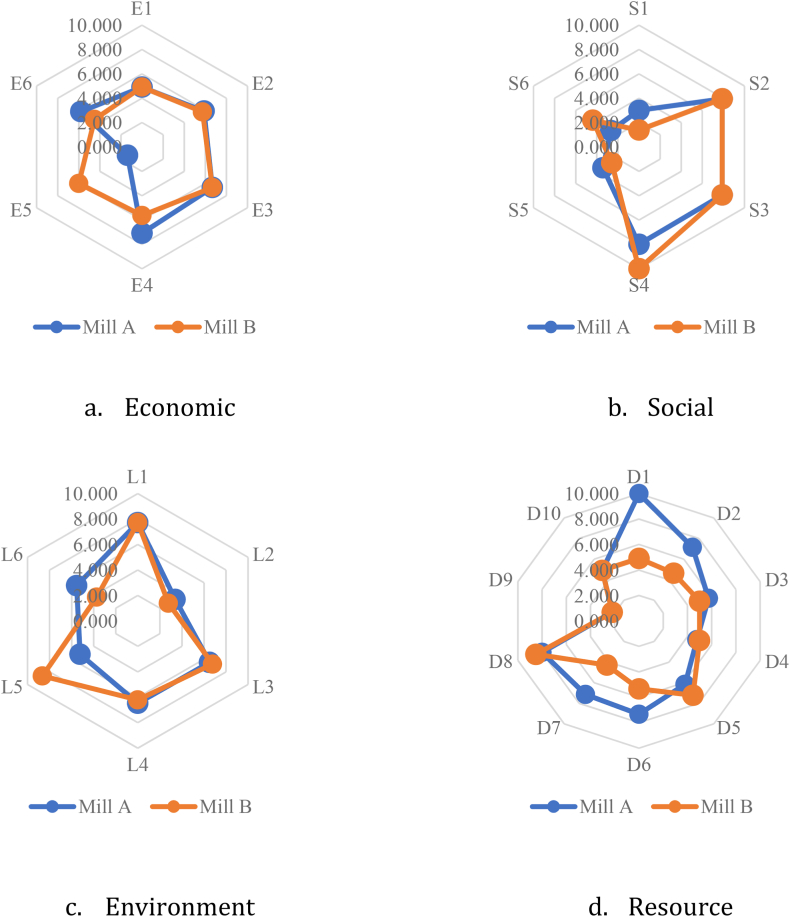

The actual data for qualitative and quantitative indicators presented above are then normalized on a scale of 0–10, following the Multi-Dimensional Scaling model [78], using Equation (1). The normalized values of each multi-dimension's indicators on the [0,10] scale can be seen in Fig. 7. There are two industries compared in terms of their sustainability performance in each dimension. Mill A and Mill B show performance variations that need further analysis to obtain the actual scores for each sustainability dimension.

Fig. 7.

Sustainability indicators score.

The multi-dimensional scaling framework analyzes each indicator to obtain performance scores for each dimension. The results of the sustainability performance assessment at the multi-dimension level can be seen in Table 7 and illustrated at Fig. 8. On average, Mill A and Mill B have performance scores that are considered quite sustainable (50–75%). When compared to previous studies by Ref. [25], the sustainability scores in each dimension are relatively lower. Current supply chain sustainability dimensions performance is lower than previous research. In this situation, there is an opportunity to improve the sustainability performance of the industry through leverage approaches provided in the MDS model. This aspect will be discussed in the following sub-section.

Table 7.

Sustainability dimensions score for Mill A and Mill B.

| No | Dimension | Mill A |

Mill B |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Description | Score | Description | ||

| 1 | Economic | 57.49 | Quite sustainable | 59.31 | Quite sustainable |

| 2 | Social | 64.32 | Quite sustainable | 61.03 | Quite sustainable |

| 3 | Environment | 60.56 | Quite sustainable | 57.50 | Quite sustainable |

| 4 | Resource | 55.07 | Quite sustainable | 64.63 | Quite sustainable |

Fig. 8.

Sustainability dimensions performance for sugarcane agroindustry supply chain.

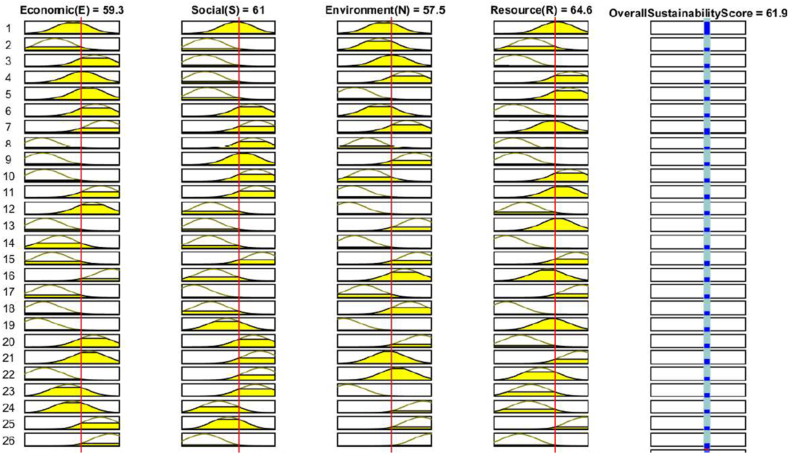

The overall supply chain performance simulation in two environments of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain will be conducted using the ANFIS model. The ANFIS model was developed using a grid partition model with 26 rules and demonstrated an excellent accuracy after undergoing various tests [25]. The ANFIS framework for aggregating the performance values of sustainability in the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain can be observed in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Overall supply chain sustainability system assessment model.

Using ANFIS model to aggregate the overall supply chain sustainability performance is performed in focal company of the sugarcane agroindustry. In mill A, it is observed that overall supply chain sustainability performance is 57.2, as depicted in Fig. 10. At mill B, the simulation of the overall supply chain sustainability performance shows a 61.9, as indicated in Fig. 11. The overall supply chain sustainability performance value in mill B is better compared to mill A. Overall, the sustainability performance values in both agro-industries indicate a “quite sustainable” range (50–70), which suggests opportunities for further improvement in their performance. Moreover, comparing with the sugarcane supply chain sustainability performance by Ref. [25], it is observed that the performance is 68.58. Consequently, there is a need for supply chain sustainability improvement to enhance its overall performance.

Fig. 10.

Supply chain sustainability performance for mill A.

Fig. 11.

Supply chain sustainability performance for mill B.

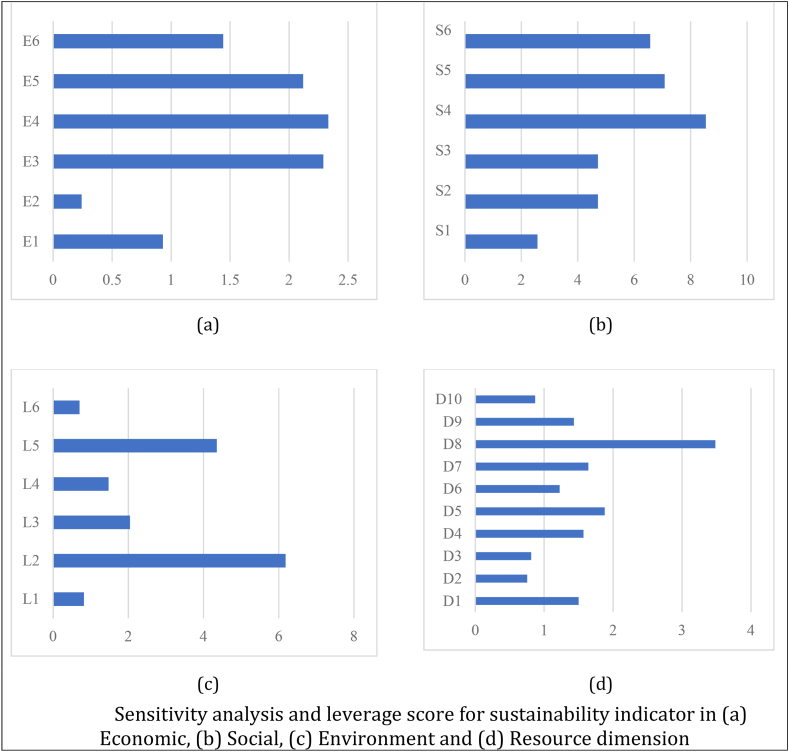

4.3. Sensitivity analysis and sustainability improvement initiatives

Supply chain sustainability performance improvement initiatives are necessary by looking at the performance analysis result of multi-dimensions and overall performance. The efforts to improve the performance of the sustainable supply chain in the sugarcane agro-industry are synthesized by each sustainability dimension, considering key indicators, examining the potential for performance improvement, which is then validated through focus group discussions with experienced experts and field observations.

Considering the limitations of previous research in formulating improvements for sustainable performance, this study proposes a combination of leverage analysis and fuzzy cognitive maps (FCM), which is then validated through focus group discussions with experienced experts from academia, practitioners, community, and the government. There were three rounds of focus group discussions conducted in formulating strategies to enhance the performance of the sustainable supply chain in the sugarcane agro-industry. These rounds included: (1) dissemination of sustainable supply chain performance measurement results along with the establishment of key indicators, (2) formulation of key activities based on the key indicators, and (3) formulation of performance improvement strategies and their socialization with relevant stakeholders.

The supply chain sustainability analysis for each dimension in both industries ranges from 50 to 70 (quite sustainable), which has the potential to be further improved. As part of the efforts to enhance performance, a leverage analysis is conducted, which is a continuation of the multidimensional scaling analysis. The leverage analysis is a sensitivity analysis in the MDS model which is able to identify the most contribute indicators in improving sustainability performance [50,78]. In this study, the leverage analysis is also employed to identify key indicators that have the highest impact on improving sustainability performance in each dimension. The results of the leverage analysis can be seen in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Sensitivity analysis and leverage score for sustainability indicator in (a) Economic, (b) Social, (c) Environment and (d) Resource dimension.

In each dimension, 50% of the key indicators are determined, which are contributed as the most sensitive in improving sustainability performance based on the leverage score mentioned above. Additionally, these key indicators are also validated by experts through the focus group discussions (FGD). The key indicators (KI) and the key activities for each key indicator are described at Table 8.

Table 8.

Key indicator and key activity (KA) for supply chain sustainability improvement.

| No | Key indicators | Key activities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Fair Profit allocation among stakeholders | KA1 | Stakeholder's requirement analysis |

| KA2 | Information transparency regarding risks and added value for all stakeholders. | ||

| KA3 | Development of a blockchain system for transaction transparency in the supply chain. | ||

| KA4 | Coordination and collaboration among stakeholder | ||

| KA5 | A mutually beneficial sugarcane purchasing system using direct selling or contract selling | ||

| E4 | Sugarcane price benchmark for farmer | KA6 | Government assistance to farmers regarding sugarcane cultivation inputs (fertilizers and seedlings). |

| KA7 | Implementation of Good Agricultural Practices to enhance land cultivation efficiency in plantation processing. | ||

| E5 | Supply chain Agility | KA8 | Expansion of sugarcane plantation areas through cooperation schemes/land use permits. |

| KA9 | Adaptation of an advanced process technology for raw sugar processing. | ||

| KA10 | Subsidies for labor financing in harvesting and transportation through the sugar mill | ||

| KA11 | Adoption of adaptive technologies to business development. | ||

| KA12 | Periodic evaluation of sugar factory development and revitalization plans. | ||

| S4 | Waste complaints | KA13 | Installation and maintenance of dust collectors or blowers to reduce ash dispersion. |

| KA14 | Establishment of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for waste complaint management. | ||

| S5 | Local labor employability | KA15 | CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) must be linked to training activities aimed at providing young workforce as successors. |

| S6 | Stakeholder partnership | KA16 | Strengthening the functions and roles of cooperatives and farmers' associations as supporting institutions. |

| KA17 | Availability of cooperation agreements between farmers and companies, including the Sugarcane Purchase System. | ||

| L2 | Emission | KA18 | Minimizing the use of fossil fuels or non-renewable energy sources. |

| KA 31 | Increasing self-sufficiency in the use of renewable energy. | ||

| KA 19 | Adoption of more efficient production technologies. | ||

| L3 | Noisy level | KA 20 | Provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) facilities for workers in the factory. |

| L5 | Ambient air quality | KA 13 | Installation and maintenance of dust collectors or blowers to reduce ash dispersion. |

| D1 | Resource accessibility | KA 15 | Installation and maintenance of dust collectors or blowers to reduce ash dispersion. |

| D4 | Raw material quality | KA 21 | Utilization of superior sugarcane seed varieties (suitable for the land, with high potential for Brix value/yield). |

| KA 22 | Mentoring and assistance to farmers regarding the fulfillment of sugarcane quality standards | ||

| KA 23 | Provision of incentives for the supply of sugarcane with superior quality. | ||

| KA 24 | Good harvest, loading, and transportation (HLT) management. | ||

| D5 | Overall recovery | KA 3 | Development of a Blockchain system for transaction transparency in the supply chain. |

| KA 8 | Expansion of sugarcane plantation areas through cooperation schemes/land use permits (HGU). | ||

| KA 17 | Availability of cooperation agreements between farmers and companies, which include the Sugarcane Purchase System | ||

| KA 19 | Utilization of more efficient production technologies. | ||

| KA 22 | Provision of assistance to farmers regarding the fulfillment of sugarcane quality standards. | ||

| KA 25 | Maintenance and revitalization of machinery and equipment aimed at automation. | ||

| KA 26 | The implementation of an IT-based system for monitoring performance | ||

| D6 | Raw material availability | KA 5 | Adopting a mutually beneficial sugarcane procurement system. |

| KA 8 | Increasing the sugarcane plantation area through cooperation schemes or land use permits | ||

| KA 27 | The procurement system of parent seedlings by the sugar mill for wider implementation according to farmers' needs. | ||

| KA 28 | Government support in the multiplication and dissemination of superior variety seedlings. | ||

| D7 | Ratoon level | KA 7 | The implementation of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) for improving land management efficiency in plantations. |

| KA 29 | Financial assistance schemes for ratoon removal and new planting activities. | ||

| D8 | Responsive sugarcane variety availability | KA 21 | The utilization of superior sugarcane seedlings (suitable for the land, with high potential for Brix value/yield). |

| KA 30 | Collaboration with research institutions for the provision of superior seedlings. | ||

A total of 31 key activities have been formulated to address sensitive issues and key sustainability indicators in the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain. In order to following the fuzzy cognitive maps approach, these key activities are then mapped out to achieve the goal in improving the sustainability performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain, as depicted in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Causal diagram of key activities for improving supply chain sustainability.

FGD series are employed to validate the causal diagram and its relationship among others. Consequently, experts are required to assist in (1) validating the causal diagram, (2) provide relationship and assessment of key activities, and (3) validating the final results of the supply chain sustainability improvement initiatives. Experts assessed the relationship of key activities using fuzzy cognitive maps (FCM) frameworks. The analysis and final score of the key activities are calculated using direct and indirect impacts and relationships that has validated through FGD series. Using FCM calculation and fuzzy assessment scales in Equations (5)–(15), experts provide the assessment. Finally, the indicators that have a significant impact on improving the sustainability of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain can be identified.

The example of the FCM calculation is provided as follows: Key activities number 6 is illustrated as an example. KA27 has a relationship to KA26 to achieve goals. KA27 has two alternatives: direct to the goals or indirect within KA26. Using Eqs. (5), (6)), the calculations are provided as follows:

| KA27 → Goals |

| I1(KA27,G) = {e(KA27,G)} |

| I1(KA27,G) = min{Very High} |

| KA27→KA26→G |

| I2(KA27,G) = {e(KA27, KA26),(KA26, G)} |

| I2(KA27,G) = min{Medium, Very High} |

Total effect of KA27 to goals:

| T(K27, G) = max{ I1(KA27,G), I2(KA27,G)} = Very High |

The result shows that the relationship between KA27 to goals is positive VeryHigh. Linguistic labels of fuzzy assessment from “very high” then transform into crisp number. The detail of the process has been explained clearly in Marimin et al. [79]. From the FCM process, it found that there are 19 key activities that have the highest score and contribution to achieving goals in improving supply chain sustainability performance.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted with experienced experts to validate the indicators that significantly contribute to improving the sustainability of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain. The experts in the FGD also formulated strategies for enhancing the supply chain sustainability based on the current conditions, desired conditions, and the involvement of relevant stakeholders. Based on the analysis, FCM analysis reveals 19 key activities with the highest contribution. This research proposes five clusters of recommendations that can be suggested to improve the performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain: raw material provision, harvesting and post-harvest activities, production process optimization, IT-based technology implementation, and institutional aspects. In detail, the recommendations and the involved actors proposed for enhancing the sustainability performance of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain can be seen in Table 9.

Table 9.

Supply chain sustainability improvement recommendations.

| Cluster | KA | Description | Proposed recommendations | Actors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw material provision | 7 | The implementation of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) for improving land management efficiency in plantations. |

|

Government, local government, farmers' cooperative organization and farmers association |

| 8 | Expansion of sugarcane plantation areas through cooperation schemes/land use permits.• |

|||

| 28 | Government support in the multiplication and dissemination of superior variety seedlings. |

|

Government, research institution, and sugar mill | |

| 28 | Government support in the multiplication and dissemination of superior variety seedlings. |

|

Research institution | |

| 30 | Financial assistance schemes for ratoon removal and new planting activities. | |||

| 31 | Collaboration with research institutions for the provision of superior seedlings. | |||

| Harvesting and post-harvest activities | 22 | Provision of assistance to farmers regarding the fulfillment of sugarcane quality standards. |

|

Sugar mill |

| 17 | Availability of cooperation agreements between farmers and companies, which include the Sugarcane Purchase System |

|

Sugar mill, farmers association and smallholder | |

|

Research institution, university, sugar mill, smallholder, and government | |||

| Production process optimization | 9 | Adaptation of an advanced process technology for raw sugar processing. |

|

Sugar mill |

| 12 | Periodical evaluation of sugar factory development and revitalization plans. |

|

Sugar mill and government | |

| 18 | Minimizing the use of fossil fuels or non-renewable energy sources. |

|

Sugar mill | |

| 18A | Increasing self-sufficiency in the use of renewable energy. | |||

| 19 | Adoption of more efficient production technologies | |||

| IT-based technology implementation | 3 | Development of a blockchain system for transaction transparency in the supply chain. |

|

University, Research institution, Government, Sugar mill |

| 11 | Adoption of adaptive technologies to business development. |

|

Sugar mill, government, and research institution. | |

| 26 | The implementation of an IT-based system for monitoring performance | |||

| Institutional aspect | 1 | Stakeholder requirement analysis |

|

Research institution |

| 2 | Information transparency regarding risks and added value for all stakeholders. |

|

Farmer Association, Farmer's cooperation organization, Government | |

| 4 | Coordination and collaboration among stakeholder |

|

Local government | |

| 16 | Strengthening the functions and roles of cooperatives and farmers' associations as supporting institutions. |

|

Farmers cooperative organization |

The assessment and formulation of efforts to enhance the sustainability of the sugarcane agro-industry supply chain have provided recommendations for improving sustainability performance that can be implemented by various relevant stakeholders. First, in terms of raw material supply, the proposal for new and superior varieties is crucial to ensure the availability of raw materials. Unique superior varieties that are tailored to specific land conditions should be prioritized in future work to enable farmers to maximize the quality of sugarcane produced, and sugar mills to achieve maximum sugar yield. In addition to variety improvement, the government, farmers' cooperation and associations, and sugar mills are also striving to ensure the availability of facilities for small-scale sugarcane cultivation while promoting best practices in sugarcane farming. Sugar mill and sugarcane smallholder are needed to build up a strong partnership connection to produce high-quality sugarcane to extract at the mill. With the partnership between these two stakeholders as may improve the sustainability of the supply chain and provide products as the consumer requirement. This is also in line with Allenbacher and Berg [80] that only cooperation and partnership practices that effective to enhance the sustainability initiative.