Abstract

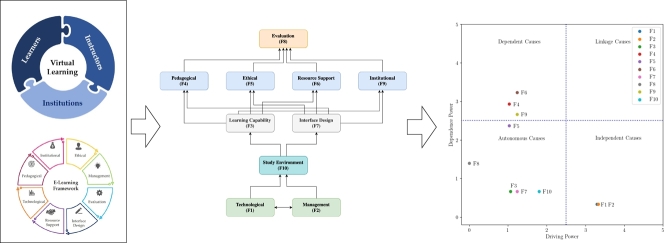

The COVID-19 pandemic's consequences have led to a global change in educational settings towards online learning. The utilization of virtual learning (VL) has increased significantly. This study aimed to extract the success factors of VL and also examine the relationships among them. The research method involves examining factors identified in the literature review and seeking confirmation from experts using the Content Validity Index (CVI) method. Ten success factors are extracted and confirmed, including Technological, Management, Learning Capability, Pedagogical, Ethical, Resource Support, Interface Design, Evaluation, Institutional, and Study Environment. Based on the Interpretive Structural Model (ISM) method and the fuzzy matrix of cross-impact multiplications applied to classification (MICMAC), which divides the factors into five levels, the relationship between these factors is examined. Level I emphasizes the importance of evaluation mechanisms. Level II stresses integrating pedagogical, ethical, resource support, and institutional aspects. Level III highlights the alignment of learner capabilities with platform interfaces. Level IV underscores the significance of the learning environment. Lastly, Level V emphasizes the interplay between technology and management in VL's expansion. The findings of this study can be developed and customized through collaboration among instructors, learners, and institutions. Moreover, the findings from correlating success factors can be applied in practical learning experiments or utilized to develop efficient modeling manuals.

Keywords: Virtual learning, Teaching/learning strategies, 21st century abilities, Distance education and online learning

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This work aims to extract the success factors of Virtual Learning (VL) and examine their relationships.

-

•

The methodology uses Delphi, ISM, and fuzzy MICMAC for factor analysis and relationships.

-

•

Success factors in VL are categorized into five levels, focusing on various aspects and technologies.

-

•

Findings suggest implementing a VL model focused on efficiency and quality, applying practical research to enhance outcomes.

1. Introduction

Global education has been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. Nevertheless, this alteration has the potential to facilitate the emergence of a more effective and adaptable educational framework [2]. The current circumstances have driven distance education into full digital integration. Internet technology is now employed extensively for delivering educational content, encompassing tools like Online Distance Learning, Video Conferencing, and Virtual Learning or VL [3], [4]. In this digital era, distance education offers remarkable flexibility and effectiveness, allowing learners to access their studies at their convenience, anytime and anywhere. In addition, learners derive advantages from the cost-effective availability of a wide range of information and learning tools in comparison to conventional forms of education [5], [6], [7], [8]. However, a drawback of distance learning remains the limited interaction among classmates and with instructors, along with challenges related to the availability of learning materials, equipment, and issues concerning educational equity [9], [10], [11].

E-Learning and VL are forms of online education that are gaining popularity these days, yet they differ significantly [12]. E-Learning centers around self-paced learning without direct interaction. Learners can study anywhere, anytime with an internet connection, utilizing teaching media like pre-made videos, games, and various tests [13]. In contrast, VL places emphasis on collaborative learning. Learners actively engage with learners and classmates as the primary learning activities within a virtual classroom. During the recent pandemic, VL has become increasingly prevalent worldwide, to the extent that it has become a norm [14]. VL is a new educational approach that supports teaching and learning by leveraging digital platforms and technologies [7]. Primary benefit of VL is its flexibility to learners, allowing them to engage in their education at any given time and location, resulting in time and cost savings [15]. This entails ensuring that all learners are afforded equitable access to educational opportunities [16].

VL is classified into two main categories: asynchronous and synchronous. Asynchronous virtual courses provide flexibility by enabling participants to connect with content and one another at their own time, whereas synchronous online learning spaces include immediate and simultaneous interactions [17]. These categories comprise conventional instructional and educational activities conducted within physical classroom settings. Learners can retrieve visual and audio content directly linked to their educational materials via computer networks and telecommunications technologies [18]. Moreover, the learners can engage in discussions with their instructor and classmates in various geographic places while adhering to the instructor's advice on their personal computers [19]. The efficacy of communication technology and the Internet are crucial for VL, as it relies on a network infrastructure [20].

Previous studies have indicated that VL yields mixed academic performance outcomes, with both successful and unsuccessful students in VL classes [21]. In each VL classroom, a multitude of factors influences student success [6]. To address this challenge and enhance the success rate of VL, it is imperative to gain a comprehensive understanding of these influential factors. Therefore, this work encapsulates two primary objectives:

-

1.

To classify and define the essential success elements that support VL environments.

-

2.

To examine and understand the relationships among these identified success factors to provide insights for optimizing VL in educational settings.

To performance this study, an examination of the key stakeholders, including learners, instructors, and educational institutions, reveals distinct roles and mutual influences [22]. Thus, the aim of this research is to look into the factors associated with these three significant stakeholders. It employs a framework of online learning standards aligned with Khan's accepted online learning standards [23]. The research employs a combination of methods, including a Delphi survey, Interpretive Structural Model (ISM), and fuzzy matrix of cross-impact multiplications applied to classification (MICMAC), to analyze and establish the relationships among these factors [24].

This study's advantage lies in demonstrating how success factors impact each crucial element's contribution. The results can also be used to guide the creation of customized teaching tactics and approaches for training settings or coursework. Additionally, these research findings may serve as the foundation for a comprehensive guidebook outlining proficient VL management methodologies.

This work is organized into the following sections. Section 2 provides an in-depth analysis of the corpus of research on VL and examines several aspects that have contributed to its success. The research technique is explained in Section 3, and the model development using ISM and fuzzy MICMAC analysis is the main topic of Section 4. Insights into the noteworthy results of using the ISM and fuzzy MICMAC analysis are provided in Section 5, along with recommendations for additional research. Finally, Section 6 presents the work's conclusion.

2. Literature review

In the modern educational landscape, we are observing a significant shift towards a future-oriented paradigm. This transformation has been expedited by integrating technology, especially in response to the global pandemic, leading to the widespread adoption of VL in traditional classrooms [15]. The VL, a natural progression from distance education, encompasses multiple components that collectively contribute to its effectiveness in facilitating successful learning experiences. These factors involve various stakeholders, including learners, instructors, and support systems, each playing essential roles in shaping the VL environment [25]. We have gathered a substantial body of relevant knowledge across various dimensions of VL, including the research process that will be used to identify significant success factors that are appropriate for this research. Details of this study and review are as follows.

2.1. Key stakeholders in VL

In VL, stakeholders play a crucial role in shaping experiences and driving success. Stakeholders of VL have three main roles including learners, instructors, and institutions as shown in Fig. 1. Let us delve into the vital contributions of learners, instructors, and institutions, exploring the rationale behind their involvement.

Figure 1.

Virtual learning's key stakeholders.

Firstly, learners are more than passive recipients of knowledge in VL. Their active participation fosters a sense of ownership and fuels motivation. Their diverse perspectives enrich the learning environment, ensuring inclusivity and catering to various learning styles [12]. By incorporating learner feedback into VL environment design and content, institutions provide an experience that resonates with their needs and preferences. This feedback loop and learner engagement in discussions and activities lead to continuous improvement and a VL environment that truly serves its purpose.

With their wealth of pedagogical expertise, instructors breathe life into the virtual space. They design engaging lessons and activities, adapting content to suit learners' needs and preferences. Their role as content creators allows them to curate existing materials or develop new ones specifically for the VL, ensuring accuracy, relevance, and accessibility. Furthermore, instructors act as facilitators, guiding discussions, providing personalized feedback, and offering support to learners navigating the virtual landscape [26]. Their active presence fosters interaction, collaboration, and a deeper understanding of the content.

Finally, institutions provide the scaffolding for successful VL. They establish the vision and direction, aligning the VL environment with their educational goals. By allocating necessary resources like technology, infrastructure, and personnel, they create a platform conducive to learning [27], [28]. Furthermore, institutions champion ongoing evaluation and innovation. They analyze data and learner feedback to identify areas for improvement, constantly refining the VL environment by adopting new technologies and incorporating evolving pedagogical approaches. This dedication to ongoing enhancement guarantees that the VL setting stays pertinent and effective.

Learners, instructors, and institutions form a synergistic triad in the VL ecosystem. By understanding the unique contributions and rationales behind their involvement, we can foster a collaborative environment where learner needs are met, instructors can effectively guide their students, and institutions can provide the tools and support for success. When these stakeholders work in unison, VL can truly reach its full potential, profoundly transforming education and impacting lives.

2.1.1. Learners

Within this context, the term “learners” encompasses individuals who are enrolled in courses, e.g., students and participants in the course [29]. Learners are responsible for self-directed knowledge acquisition, which includes setting learning objectives and effectively pursuing them [30], [31]. Additionally, learners should be able to collaborate with peers within the VL environment. The learners serve a role as a significant indicator of the course's success [32]. Hence, learners can only succeed in their studies by receiving accurate knowledge transfer from their instructors. Moreover, they require adequate institutional support and guidance throughout their educational journey [33].

2.1.2. Instructors

In this context, the term “instructors” refers to those who hold the positions of lecturers, teachers, mentors, and teaching coaches. These individuals are entrusted with the responsibility of imparting knowledge to learners. Instructors have duties in creating and producing instructional materials [34]. To effectively facilitate learning for learners, instructors must possess a comprehensive understanding and mastery of technological tools, while also cultivating an interactive and stimulating educational setting. Through the execution of these responsibilities, instructors have the capacity to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge and promote achievement among learners [35], [36]. The role of instructors in VL requires support from the institution and staff, including the need for students to respond positively to their teaching [37].

2.1.3. Institutions

The term “institutions” in this context include people in various roles within departments, universities, faculties, and schools, as well as administrators and support staff [14]. The provision of knowledge and practical communication influences the effectiveness of learning. Guiding and assisting learners in educational and technical domains, including technical support for using virtual education platforms, is very important [38]. Another crucial element is effectively managing people to support the program or course. Allocating financial resources to VL includes carefully considering and procuring appropriate technological tools and platforms that create effective educational experiences. Establishing effective teaching and learning management is a crucial cornerstone in facilitating academic success for both learners and instructors [39].

Besides examining the key stakeholders influencing the effectiveness of VL, it is crucial to consider critical factors related to training. Online education adheres to numerous standards set by various national organizations, widely recognized, and rigorously upheld in the educational research community. Nonetheless, there have been innovations in creating E-learning models primarily concentrating on instructor-related administration and planning. Scholars recognize the importance of adopting these criteria, and the following section will offer a detailed explanation.

2.2. Khan's E-learning framework

A methodology for creating and delivering online courses is Khan's E-learning framework [37], [40]. The model has eight elements, as shown in Fig. 2. It is based on the following processes. Creating an E-learning course's learning objectives is the first step in the methodology. The participants in the online course will be examined in the following stage [23]. The next stage is to choose the relevant content after figuring out the students and the learning objectives. Instructors may now select course materials for E-learning courses and the knowledge required for learners to achieve their objectives. The next step is to create an effective, entertaining, and explicit content delivery sequence for the E-learning course [40]. In addition, Khan's E-learning framework includes a method for selecting the media for E-learning course presentations. The most effective means of delivering information to learners are required. Creating the course material, interface design, and course testing are all parts of developing the E-learning course [41]. E-learning course development must be followed by implementation, providing learners with accessibility and assistance. The final step of the framework is to assess whether an E-learning course meets learner objectives effectively.

Figure 2.

Khan's E-learning framework.

While valuable in specific contexts, Khan's E-Learning framework may not be well-suited for VL. The framework's primary emphasis on video-centric, instructor-led, and structured content delivery does not align with the diverse and interactive nature of VL [42]. VL often requires a broader range of instructional strategies, including text-based content, interactive simulations, and live virtual sessions, which Khan's framework may need to address adequately. Moreover, VL demands a solid pedagogical foundation, personalized learning pathways, and a focus on accessibility, which might not receive comprehensive coverage within Khan's framework [43], [44]. Additionally, this framework mentions only the administration of the department and the instruction of the instructor, leaving out the students' principles of practice.

Nevertheless, Khan's E-Learning framework does offer valuable insights into essential components for E-learning success. These factors, highlighted in the framework, can still provide valuable considerations for related work in the field of VL. Researchers should adapt and expand upon these insights while exploring alternative instructional design models better suited to VL's unique requirements for more effective and engaging VL experiences.

2.3. Related work

Technology and distance education have significantly changed how we teach and learn. This makes an in-depth examination of the advantages and disadvantages of incorporating technology into education necessary. Many research projects aim to increase the effectiveness of online learning by investigating various facets and methods. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies examined various facets of online education. Three critical success requirements for online delivery were found in an early study by Volery and Lord [45]: teachers, technology, and technology utilization. According to Volery and Lord, teachers will maintain their significant role in education, as observed from students' perspective. A previous study by Menchaca and Bekele [46] showed that having various tools available to improve a learning environment's flexibility is crucial to its performance. Technology should be incorporated in a way that accommodates various learning styles. To bolster this idea, a study examining the many factors impacting student satisfaction in online educational programs was carried out by Freeman and Urbaczewski [47]. The period covered by the data gathering and analysis was 2009–2014. This study investigated the impact of seven critical success criteria on students' happiness. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, virtual and online learning have been increasingly common in schools. However, this shift has brought about notable alterations in instruction and learning practices, intensifying the identification and adaptation of success criteria by the prevailing circumstances.

Prior research on success factors has used structural modeling tools to examine a variety of processes, including those carried out by Ahmad et al. [48] and Bhatt et al. [49], in order to determine how well-prepared students are for online learning. Ahmad assessed the relative importance of the many components that go into making university administration effective in the context of online learning. This investigation employs ISM and MICMAC approaches to construct an ISM model, facilitating a comprehensive comprehension of the interconnections among pivotal elements within E-learning. Bhatt's research mostly centers on the learner, particularly emphasizing very recent and specific findings. The outcome of this study exhibits distinctive aspects that are seldom observed in other research endeavors. Notably, the variables of openness to experience, generosity, and extraversion demonstrate a noteworthy influence on the determination of student preparedness. Through the use of a similar methodology, these two activities exhibit antecedent results that exert an impact on several other aspects. Furthermore, Guo et al. [50] employed the ISM approach to examine the many components that influence student motivation. The MICMAC technique has revealed three characteristics that are the primary determinants influencing students' desire to utilize technology. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that this specific approach includes analyzing negative factors, as shown in [51], which applies the ISM method to assess ten common challenges in E-learning. The results also highlighted difficulties in accurately discerning the intricacies involved in decision-making. The presence of ambiguity and personal prejudice constitutes a significant concern.

Previous studies have examined various aspects of success and barriers in different contexts, such as instructional methods and external and internal factors. The studies utilized diverse research approaches, including structural equation modeling (SEM), ISM, and literature reviews, to facilitate comprehensive discussions. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of comprehension regarding the connections between various factors contributing to success, specifically within immersive learning. Therefore, this work aims to investigate the correlations among various factors contributing to success in the context of VL.

2.4. Factor analysis

Factor analysis is a helpful statistical method that researchers employ to reduce complex data and comprehend the relationships between various variables. In this subsection, we will compare two popular approaches to factor analysis: ISM and SEM.

ISM adopts a qualitative approach, relying on expert judgment and stakeholder input to define and assess relationships between elements [52], [53]. This flexibility makes it valuable when data is limited or unreliable, particularly in early-stage research or complex systems analysis. Conversely, SEM adopts a quantitative perspective, utilizing statistical data and confirmatory analysis to determine the magnitude and direction of relationships among variables, as detailed in [54]. This rigor allows for precise hypothesis testing and causal inference but necessitates theoretical solid grounding and robust data. ISM's key strengths lie in its flexibility, ease of understanding, and ability to foster stakeholder collaboration [53]. Its non-reliance on strong statistical assumptions makes it well-suited for exploring intricate systems lacking readily available data. However, its subjectivity due to expert dependence and susceptibility to bias are inherent weaknesses. Conversely, SEM boasts precision, rigor, and the ability to test causal relationships between variables [55]. However, its data-intensive nature, complex model specification, and requirement for statistical expertise pose significant challenges [54].

ISM and SEM find niche applications within the research landscape due to their different strengths and weaknesses. ISM shines in early-stage research, conceptual model development, and identifying critical drivers within complex systems. Its qualitative approach fosters discourse and allows for iterative model refinement based on stakeholder feedback. Conversely, SEM excels in testing specific hypotheses, validating theoretical models, and quantifying causal relationships [54]. Its focus on precise statistical analysis makes it ideal for mature research questions with clearly defined variables and robust data. Ultimately, the choice between ISM and SEM hinges on the research stage, data availability, and research question.

To validate the selected variables, this work uses the content validity index (CVI) technique [56]. Subsequently, factor analysis is used to explore the connections between these validated factors, employing an ISM. The ISM process enables the visualization of the hierarchical structure of components within a complex framework. Then, the strangeness of the relationship is determined by the fuzzy MICMAC technique. This discovery is precious as it helps researchers understand the intricate interplay among various elements. This progress holds the promise of enabling the creation of more refined and impactful solutions, as discussed in [57]. The upcoming section will delve into the details of the preceding study and also the methodology of this work.

3. Method

3.1. Research framework

Fig. 3 illustrates the conceptual framework, which consists of three primary elements: research framework, the work process and the study's final model. The foundational theories encompass pertinent stakeholders and Khan's E-learning Framework, serving as the initial conceptual basis for this work. The central portion of Fig. 3 illustrates the overarching workflow. It begins with factor identification, suggesting an initial phase where various potential elements impacting VL are pinpointed. This step is followed by expert selection, which indicates the involvement of domain experts to either validate or provide insights into the chosen factors. Once these experts weigh in, the process advances to factor validation, ensuring that the selected factors are relevant and significant. The next step in the process is to apply the ISM approach, which aims to ascertain the elements' hierarchical ordering. Lastly, the fuzzy MICMAC process is a culminating step aimed at further analyzing the interdependencies of the factors using a fuzzy logic approach.

Figure 3.

Research framework and work process.

3.2. Factor identification

Identifying factors was the first step in the research process. It was carried out by reviewing the articles, which were searched for terms such as “Online Learning Factor,” “Virtual Learning,” “Online Learning Success Factors,” “Key Problems of Online Learning,” and similar terms. These keywords were searched from online databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and university online library systems for 2012-2021. The literature reviews classified and categorized crucial instructional concepts by VL. Codes were allocated to facilitate clarity in subsequent procedures. All the factors and definitions derived from the systematic review are summarized and listed. The data would then be subjected to factor analysis for further analysis and interpretation, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ten virtual learning factors.

| Factor | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Technological (F1) | Technological aspects of VL encompass the digital tools, platforms, and methods employed for VL environments. It includes using internet-enabled devices, software applications, and communication technologies to deliver and facilitate educational content. The technological factor enables interactive and remote learning experiences, personalized instruction, and access to a wide range of educational resources, enhancing the effectiveness and accessibility of VL. | [27], [28], [30], [61], [62], [63] |

| Management (F2) | Management in VL refers to the systematic administration and organization of digital educational programs. It includes designing curriculum, scheduling classes, managing enrollments, monitoring student progress, and facilitating communication within VL environments. Effective course management ensures seamless access to course materials, assessment tools, and resources, optimizing the overall learning experience for learners and instructors in the VL domain. | [29], [37], [64], [65], [66] |

| Learning Capability (F3) | Learning capability for VL refers to the skills, attributes, and competencies an individual possesses that enable them to excel in a digital or VL environment. It encompasses the capacity to self-motivate, manage time effectively, navigate online platforms, critically assess digital information, collaborate with peers, and adapt to various online teaching methods. A strong learner capability for VL indicates a learner's readiness and proficiency in engaging with VL courses and resources to achieve educational objectives. | [29], [32], [63], [64], [67], [68] |

| Pedagogical (F4) | Pedagogical for VL refers to the principles, strategies, and methods applied to design and deliver impactful teaching and learning experiences within digital or VL. It encompasses instructors' techniques and approaches to engaging learners, fostering learning, and reaching educational goals via online platforms. Effective VL Pedagogical considers elements such as course structure, content delivery, assessment techniques, learner engagement, and the incorporation of technology to enhance the VL experience. | [36], [62], [66], [69], [70], [71] |

| Ethical (F5) | Ethical in VL encompasses the moral principles and standards shaping individuals' and institutions' conduct, actions, and decisions within digital or VL environments. It entails values like fairness, integrity, transparency, privacy, and responsibility in online educational practices. Ethical behavior in VL ensures that learners, instructors, and administrators uphold virtues such as honesty, respect, and equity during their involvement in or facilitation of online learning experiences. Furthermore, it addresses concerns regarding plagiarism, academic integrity, data security, and the responsible utilization of technology in education. | [62], [66], [72] |

| Resource Support (F6) | The provision of digital tools, materials, and resources to assist educators, students, and organizations in the process of teaching and learning in virtual or digital learning environments is referred to as resource support. These resources can include textbooks, multimedia content, online libraries, interactive simulations, software applications, technical support, and other digital assets aimed at enhancing the educational experience and facilitating effective online instruction and study. | [29], [30], [62], [73] |

| Interface Design (F7) | Interface design refers to the planning, creating, and optimizing the user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) elements within digital or VL environments. It involves designing the layout, navigation, and overall presentation of online educational platforms or systems to make them intuitive, user-friendly, and conducive to effective learning. A well-designed interface for VL should promote easy access to course materials, encourage user engagement, facilitate communication, and enhance the overall educational experience for both learners and educators. | [13], [28], [39], [65], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78] |

| Evaluation (F8) | Evaluation is the methodical process of evaluating and quantifying the efficiency, standards, and results of online or VL programs and courses. Analyzing a range of factors is part of this review, including the impact of technology on learning outcomes, learner engagement, instructional strategies, curriculum design, and assessment methodologies. The goal is to gather data and feedback to make informed decisions about improving VL content, strategies, and delivery, ultimately enhancing the overall educational experience for learners in VL. | [63], [66], [79], [80], [81], [82] |

| Institutional (F9) | Institutional refers to the formal framework and infrastructure of an organization or educational entity that supports VL. This includes policies, systems, technology, faculty training, and administrative structures designed to support the effective management of VL. | [26], [27], [28], [29], [63], [83], [84], [85] |

| Study Environment (F10) | Study environment encompasses the digital or physical setting where electronic education takes place. It comprises the online platform, educational materials, interactive tools, and support resources, creating a structured space for learners to access and engage with digital content. This environment facilitates effective online learning, interaction, and knowledge acquisition, offering a flexible and accessible framework for education in the digital age. | [30], [63], [64], [66], [86], [87] |

The study considers ten success factors involving three key stakeholders across all dimensions, citing related research for each factor. Additionally, the literature review reveals that, alongside success factors, there are failure factors in online and VL. These failure factors are often associated with student unpreparedness, including financial limitations, inadequate access to necessary equipment, and insufficient support, which can vary based on economic conditions in different regions. Lack of motivation and technological skills also contribute to learning inconsistency, potentially leading to discontinuation. Numerous studies investigate these failure factors that impede academic success, as cited in the literature [58], [59], [60].

3.3. Factor validation

After the completion of factor identification, the research progressed to factor verification using CVI. To ensure variable confirmation, a panel of five to ten experts with specific qualifications will be chosen to analyze and validate the factors in this initial segment [88]. These experts should have previous experience in teaching through VL during recent epidemic situations, with over five years of experience in organizing online education and specializing in either education technology or education management. Their involvement is required throughout the course duration.

A comprehensive review was conducted by seven experts, evaluating the relevance of ten elements previously discussed in the literature. These elements included Institution, Management, Technological, Pedagogical, Ethical, Resource Support, Interface Design, Evaluation, Learning Capability, and Study Environment. Further information about the experts is available in Table 2. The experts in this study comprise a diverse group with various roles and areas of expertise. They include lecturers specializing in educational technology, distance learning, information technology, and a lecturer-researcher in social science. Additionally, education support officers specialize in distance learning, network service and facility management, and educational administration. Their collective experience ranges from over 17 years to more than five years in their respective fields.

Table 2.

Background of the experts for CVI process.

| Expert | Profile/Position | Field/Expertise | Experience (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ec1 | Lecturer | Educational Technology | 17 |

| Ec2 | Lecturer | Distance Learning | 15 |

| Ec3 | Lecturer | Information Technology | 10 |

| Ec4 | Lecturer, Researcher | Social Science | 8 |

| Ec5 | Educational Support Officer | Distance Learning | 10 |

| Ec6 | Educational Support Officer | Network service, Facility | 8 |

| Ec7 | Educational Support Officer | Educational administration | 5 |

CVI is a widely used method for quantifying the content validity of a research assessment tool [56]. This assessment aims to ascertain the degree to which the items or questions within the instrument effectively and accurately reflect the intended content domain [89]. It is a tool that researchers and experts utilize to evaluate the pertinence and suitability of individual items to the construct being assessed [90]. The researchers will present research tools to experts for their evaluation and consideration. According to Polit and Beck [56], the optimal number of experts is between five and ten, with a recommendation to stay within ten due to its lack of necessity. The experts will discuss the questions, leading to the formation of a four-point opinion. Calculating the CVI entails the assignment of scores to evaluate the alignment between the factors or items within a measurement tool and the intended content domain. The potential score range spans from one to four, wherein a score of one signifies that a factor or item cannot measure the intended characteristics as defined effectively. A score of two suggests that significant revisions are necessary for adequate measurement. A score of three indicates that minor revisions are required for adequate measurement. Lastly, a score of four signifies that the factor or item perfectly measures the intended characteristics as defined. A minimum CVI value of 0.75 is selected with the endorsement of experts or professionals. According to Gilbert and Prion [91], it is suggested that the CVI value should exceed 0.70.

3.4. ISM process

After completing the CVI process, the next step in the research is to employ ISM. ISM is a powerful technique developed to enhance understanding of complex systems and streamline decision-making processes. It involves the creation of visual models that represent complex manifestations, categorize driving forces into strong, weak, and dependable, and offer a systematic approach to addressing intricate issues. ISM also provides a collaborative learning approach where group members analyze elements of interest and their relationships, which can be structured and presented as diagrams [92].

These diagrams generated by ISM illustrate the specific connections between individual components and the overall relationships among all components. This process entails identifying fundamental relationships and simplifying complex ones into an understandable structure [24]. ISM can be employed as a tool to diagnose the structure of various technical or social processes. For instance, Naveed et al. [51] used ISM and MICMAC to examine obstacles to E-learning adoption in universities. Their study aimed to identify these barriers and provided an ISM diagram to help stakeholders comprehend them. The significant barriers identified included a lack of ICT and necessary skills, poor infrastructure, insufficient technical support, and a shortage of instructional design expertise in universities.

In this work, ISM is utilized as a research instrument to analyze the factors contributing to the success of VL, as depicted in Fig. 3. This process continues once all ten factors have been confirmed through the CVI process.

The ISM factor analysis involves a distinct set of experts compared to the prior process. The criteria for selecting ISM experts specify that VL participants must include instructors with a minimum of ten years of teaching experience. Support staff in virtual education should possess at least five years of expertise. Both instructors and teaching support staff are responsible for planning, quality control, monitoring, evaluation, and curriculum development. Students with at least three years of VL experience should be proficient in theory and practical aspects, ensuring their participation from the course's inception to its conclusion, especially in light of past epidemic situations. Macmillan has determined the optimal number of experts for a Delphi methodology [93]. Given the need for a highly homogeneous panel, 10-15 experts are recommended; thus, a group of thirteen would be adequate for this endeavor.

We have designed a questionnaire to investigate what factors make VL successful. Thirteen experts, as detailed in Table 3, will analyze the relationships between these factors using the Delphi method in three rounds [94].

Table 3.

Background of the experts for ISM and fuzzy MICMAC processes.

| Expert | Profile/Position | Field/Expertise | Experience (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Academician, Researcher | Educational Technology | 12 |

| 2 | Professor | Educational Technology | 22 |

| 3 | Lecturer, Researcher | Information Technology | 15 |

| 4 | Researcher | Social Science | 9 |

| 5 | Lecturer | Interdisciplinary | 10 |

| 6 | Lecturer | Logistics | 10 |

| 7 | Education Support Officer | Network service, Facility | 12 |

| 8 | Education Support Officer | Educational administration | 8 |

| 9 | Teacher | Mathematics and Technology | 10 |

| 10 | Teacher | Foreign language | 14 |

| 11 | Student (Distance Learner) | Science | 6 |

| 12 | Student (Distance Learner) | Science | 5 |

| 13 | Student (Distance Learner) | Nursing | 3 |

The table comprises 13 experts with diverse profiles and qualifications, including positions such as academician, professor, lecturer, researcher, educational support officer, teacher, and distance learner. Their educational expertise spans areas such as educational technology, information technology, social science, interdisciplinary studies, logistics, educational administration, mathematics and technology, foreign language, and nursing. Collectively, these experts bring extensive experience to the research, with various individuals having over ten years of experience in their respective fields. They are well-equipped to analyze the relationships and factors contributing to the success of VL using ISM and fuzzy MICMAC processes.

Experts use a pair-wise comparison method to assess how different components in a system interact. This involves designating Yes (Y) or No (N) to indicate causal relationships between factors. When a relationship is confirmed as Y, a Structured Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM) is created using unique symbols to represent connection patterns between variables. The SSIM has converted these symbols into numerical values, constructing an Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM) by adding 1 to related factor cells. Then, the Final Reachability Matrix (FRM) summarizes the hierarchical relationships among factors, with top-level factors exerting more influence on those lower down the hierarchy [24].

3.5. Fuzzy MICMAC process

In the final phase of this work, the fuzzy MICMAC analysis is utilized to categorize factors according to their influence and dependency relationships, typically assigning them to categories such as Autonomous, Independent, Dependent, and Linkage Causes. Factors categorized as Driving wield significant influence within the system, while Dependent-Driven factors are heavily influenced by others [95]. The initial data for this process is derived from the FRM generated in the ISM phase. Experts assess the influences of these factors using linguistic terms. Fuzzy logic models uncertainty and imprecision in these relationships, providing a more adaptable and realistic analytical approach [96], [97]. Linguistic terms are then converted into numerical terms. Subsequently, fuzzy MICMAC computations are performed to obtain the stabilizer matrix, further elucidating the relationships and categorizations of factors within the analyzed system. This comprehensive analysis aids in understanding the dynamics and roles of various elements in the system, guiding strategic decision-making and planning.

4. Evaluation and results

4.1. Result of content validity index

The context and content validity of VL success factors were evaluated by experts. The results of expert validity tests are presented in Table 4. The provided representation signifies the sequential arrangement of the experts' evaluations and the sequential arrangement of the criteria.

Table 4.

Content Validity Index.

| Factor | Ec1 | Ec2 | Ec3 | Ec4 | Ec5 | Ec6 | Ec7 | na | ICVI | k | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.98 | excellent |

| F3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0.86 | 0.86 | excellent |

| F4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 6 | .86 | 0.93 | excellent |

| F7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

| F10 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | excellent |

The computation of the in Table 4 was conducted to assess the level of relationship and agreement for each item. This calculation involved dividing the questions into four categories on a Likert scale, which included the following ratings: four is highly relevant, three is moderately relevant, two is somewhat relevant, and one is not relevant. The experts assessed each issue based on their individual perspectives and experiences during the assessment. The following equation can be used to calculate .

| (1) |

where is the number of experts in the agreement and is the number of experts [98]. The outcome demonstrates how good these ten elements are, which are considered to be crucial elements affecting the effective VL.

In the context of the CVI, the Kappa, k, is a crucial value for adjusting the CVI to reflect content validity accurately. Kappa values, ranging from -1 to 1, signify different content validity levels. Kappa values of 0.75-1.00 indicate excellent content validity, 0.40-0.74 represent a reasonable level, 0.20-0.39 suggest moderate validity and 0-0.19 signify low validity [99], [100]. These values assist in gauging agreement among experts, ensuring the content aligns with its intended purpose, which can be computed as the following formulas.

| (2) |

where is given in Equation (1), is the probability that experts will give the same opinion by chance [88] and

| (3) |

According to the data presented in Table 4, it is evident that every overarching factor, as unanimously agreed upon by experts, surpasses a threshold of 0.80 across all items. Further examination reveals that three factors exhibit a score of 0.86, while the remaining seven achieve a perfect score of 1.00 when assessed using the formula. The resulting value of 0.96 indicates that the criteria are met at a highly satisfactory level. The researcher utilized the recommendations provided by the expert to meticulously fine-tune various factors, thereby ensuring the precision and correctness of the content. From Equations (2) and (3), we can calculate the Kappa statistic. It is observed that all ten factors displayed Kappa values surpassing 0.75, signifying excellent agreement. This underscores the questionnaire's commendable content validity, as most experts agreed when assessing most questions.

4.2. Evaluation results of ISM analysis

To examine and elucidate the interactions among factors, experts commonly employ a pair-wise comparison methodology. In this systematic approach, experts thoroughly evaluate all factors and provide comparative assessments of their associations. This evaluation involves using answer alternatives, such as designating Y to indicate that Factor A and Factor B are causally related, while N indicates that there is no relationship at all [101].

Once a causal relationship is determined as Y, a correlation table is generated through the SSIM to simplify the data. This table employs four symbols: V, A, X, and O. Each symbol corresponds to a unique connection pattern between two variables, denoted as i and j within the SSIM relationship table. These symbols, as presented in Table 5, convey specific connotations:

V signifies that variable i produces value j, without implying a reverse relationship where j produces i.

A implies that j leads to i, but not vice versa.

X denotes a bidirectional relationship that denotes dependency, with i leading to j and j leading to i.

O represents the absence of any significant correlation or association between the variables [102].

Table 5.

Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | X | V | V | O | V | V | V | O | V | |

| F2 | O | O | O | V | V | V | O | V | ||

| F3 | O | O | V | O | O | O | A | |||

| F4 | X | V | A | V | A | O | ||||

| F5 | O | O | O | O | O | |||||

| F6 | A | V | X | A | ||||||

| F7 | O | V | A | |||||||

| F8 | O | O | ||||||||

| F9 | A | |||||||||

| F10 |

After extracting data from the SSIM, the next stage is to translate the symbolic representations into numerical values to build an IRM. This IRM is generated by adding 1 to each cell in the SSIM matrix where two factors are related, as shown in Table 6. This numerical representation simplifies the relationships between factors and provides a basis for further analysis and interpretation.

Table 6.

Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Given an IRM, which captures direct relationships between elements in a system, it is also pivotal to extrapolate this to encompass indirect or transitive relationships. The FRM, representative of this comprehensive relationship network, is obtained by applying Warshall's Algorithm to the initial matrix [103]. This algorithm considers each element an intermediary bridge, systematically updating the matrix to encapsulate pathways where one element can influence another through a chain of intermediates. By the algorithm's conclusion, the matrix no longer merely showcases direct influences but illuminates the complete landscape of potential influence on both direct and transitive elements. The FRM serves as the ultimate step in displaying the relationships among all factors within a system. This matrix is presented in a tabular format, as depicted in Table 7. The FRM table provides a clear representation of the hierarchical relationships among factors, revealing the influence of each factor on others. Factors positioned at the top of the hierarchy significantly influence lower-down factors, illustrating the hierarchy's structure and the relative importance of each element within the systems.

Table 7.

Final Reachability Matrix (FRM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 |

| F2 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 0 |

| F5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 1* | 0 |

| F6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 0 |

| F8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 |

| F10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 |

In Table 7, the FRM details the relationships among ten distinct factors labeled as F1 through F10. Each cell within the matrix indicates the influence between two factors: a value of 1 suggests that the factor represented by the row can influence the factor represented by the column. Notably, entries marked with an asterisk (*) highlight transitive relationships, signifying that the influence between the two factors is indirect, channeled through one or more intermediary factors. This matrix, thus, offers a comprehensive view, capturing both direct and transitive interactions and elucidates the intricate web of dependencies among the system's factors.

Level partitioning of the FRM is a methodical process that categorizes elements into distinct hierarchical levels based on their influence and dependencies within a system. For each element, one initially determines the reachability set, which encapsulates all the elements it can influence, and the antecedent set, representing all elements that influence it. The intersection of these two sets for each element is then compared with its reachability set. Elements for which these are identical form the top level, as they are uninfluenced by any other remaining elements in the matrix. Once identified, these top-level elements are conceptually set aside, reiterating the process with the remaining elements. This methodical process is repeated until each component is assigned to a unique hierarchical level. This produces a graphic depiction of dependencies, where the highest levels are the least dependent on other system elements, while the lowest levels are becoming more impacted by them.

A methodical level partitioning of the reachability matrix yields Table 8, which shows the hierarchical organization of the system's factors, F1 through F10. The reachability of each factor set defines variables that it can affect, including explicit and transitive relationships. Conversely, the Antecedent Set enumerates factors from which it derives influence. The Intersection column, capturing the overlap of these sets, plays a pivotal role in the hierarchical categorization. Factors that exclusively intersect in reachability, indicating they are not influenced by other factors yet to be categorized, are classified into a unique hierarchical level.

Table 8.

Level partition on reachability matrix.

| Factor | Reachability Set | Antecedent Set | Intersection | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F2 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F3 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 10 | 3 | |

| F4 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | |

| F5 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | |

| F6 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | |

| F7 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 7, 10 | 7 | |

| F8 | 8 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 8 | I |

| F9 | 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | |

| F10 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 1, 2, 10 | 10 | |

| F1 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F2 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F3 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 10 | 3 | |

| F4 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | II |

| F5 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | II |

| F6 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | II |

| F7 | 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 | 1, 2, 7, 10 | 7 | |

| F9 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 4, 5, 6, 9 | II |

| F10 | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 | 1, 2, 10 | 10 | |

| F1 | 1, 2, 3, 7, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F2 | 1, 2, 3, 7, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F3 | 3 | 1, 2, 3, 10 | 3 | III |

| F7 | 7 | 1, 2, 7, 10 | 7 | III |

| F10 | 3, 7, 10 | 1, 2, 10 | 10 | |

| F1 | 1, 2, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F2 | 1, 2, 10 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | |

| F10 | 10 | 1, 2, 10 | 10 | IV |

| F1 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | V |

| F2 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | 1, 2 | V |

The table elucidates this layer-by-layer segregation. Initially, factor F8 is identified as Level I, signifying its role as a primary, uninfluenced driver. Subsequent sections demarcate Level II to Level V, each encapsulating factors with analogous influence patterns. Ultimately, this methodical partitioning offers a clear, hierarchical perspective on the interplay among the ten factors, with upper levels less influenced by others and progressively more influential as we descend the hierarchy.

From Table 7, Table 8, we can interpret and construct the ISM model as shown in Fig. 4. The presented diagram provides a visual hierarchy of ten fundamental factors pivotal to VL. At the summit, represented by an amber block, is the Evaluation (F8) factor, underscoring its primacy as a driving influence in the VL model.

Figure 4.

ISM of VL success factors.

Adjacent to this apex, four factors, including Pedagogical (F4), Ethical (F5), Resource Support (F6), and Institutional (F9), are denoted in blue blocks, emphasizing their essential roles and the extent to which the overarching Evaluation factor might influence them. The mid-tier is occupied by Learning Capability (F3) and Interface Design (F7), represented in white blocks. These factors play intermediate roles in the VL dynamic, influenced by those above while potentially influencing those below.

Towards the base, Study Environment (F10) bridges the gap between the intermediate and foundational factors. Finally, grounding the hierarchy is Technological (F1) and Management (F2) factors, depicted in green blocks, indicating their roles as foundational elements within the VL ecosystem, most influenced by the collective interactions of the factors above. Collectively, this visual structure delineates the intricate interrelationships and influence patterns integral to the VL domain, offering readers a clear and structured understanding of the system's dynamics.

4.3. Success factor relation using fuzzy MICMAC

The process of conducting fuzzy MICMAC analysis involves several key steps. The analysis must be prepared using the Binary Direct Relationship Matrix (BDRM) method. In constructing the BDRM, one initiates with the IRM, which delineates direct influences among factors. This matrix is then refined diagonal elements, which represent self-influence, to 0. From the IRM in Table 6, we can construct the BDRM as shown in Table 9. This resultant matrix succinctly encapsulates the immediate relationships between factors, offering a streamlined view essential for advanced interpretative structural analyses.

Table 9.

Binary Direct Relationship Matrix (BDRM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| F7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Determining the level of relationship among the factors in the MICMAC process is a crucial step. Traditional correlation between factors yields binary scores of 1 and 0, indicating influenced or uninfluenced relationships, respectively. In contrast, fuzzy MICMAC utilizes the linguistic scale principle to introduce degrees of correlation equal to 1, increasing the granularity of relationships. The linguistic scales of this work are shown in Table 10. In order to create the Fuzzy Direct Relationship Matrix (FDRM), which is displayed in Table 11, experts rate the correlation levels based on variables and assign a degree of membership weight for each pair of links using linguistic scale principles.

Table 10.

Linguistic scale for fuzzy MICMAC.

| Relationship | No Influence | Very Week | Week | Medium | Strong | Very Strong | Complete Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale value | 0 | 0.133 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.867 | 1 |

Table 11.

Fuzzy Direct Relationship Matrix (FDRM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.867 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.5 |

| F2 | 0.333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.867 | 0.5 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 | 0 |

| F5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.133 | 0.5 | 0 |

| F7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 |

| F8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F10 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 |

After obtaining the degrees of correlation between success factors, the analysis assesses direct and transitive relationship effects through fuzzy MICMAC relationships. Iteratively multiplying the FDRM results in a stabilized matrix until the driving powers and dependence weights stabilize. The formula employed for determining the magnitude is expressed as

| (4) |

where i and j are integers ranging from 1 to n, and c is an integer greater than or equal to 2. In this formula, denotes the strength of the direct relationship between factors i and k.

Equation (4) yields the Fuzzy Stabilized Matrix (FSM), which offers insights into the dependence and driving powers of each factor within Virtual Learning (VL) ecosystems, as illustrated in Table 12. Then, by adding up the values in this matrix's rows and columns, the driving and dependency powers are determined. The outcomes of this procedure are depicted in a visual representation called a conclusive dependence–driving power diagram presented in Fig. 5.

Table 12.

Fuzzy Stabilized Matrix (FSM).

| Variables | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | F9 | F10 | DRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.867 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.5 | 3.533 |

| F2 | 0.333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.867 | 0.5 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 | 2.533 |

| F3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 | 0 | 0.766 |

| F5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| F6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.133 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.633 |

| F7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 | 0.966 |

| F8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.333 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.833 |

| F10 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.133 | 0 | 1.833 |

| DEP | 0.333 | 0.7 | 1.567 | 1.666 | 0.5 | 3.166 | 1.5 | 0.732 | 0.766 | 1 | |

Figure 5.

Conclusive dependence–driving power diagram.

The classification of important VL variables according to their corresponding driving and dependence powers is shown in Fig. 5. Such a categorization offers an analytical perspective into these factors' interplay and influence dynamics within the VL ecosystem.

-

1.

Dependent Causes Quadrant: This encompasses factors that predominantly demonstrate a higher susceptibility to external influences while their capacity to exert influence remains limited. Factors like Pedagogical (F4), Resource Support (F6), and Institutional (F9) are delineated here, emphasizing their dependency on other pillars of the system for optimal functionality.

-

2.

Linkage Causes Quadrant: Interestingly, no factor occupies this quadrant. This suggests that within the examined parameters, no factor influences and is simultaneously influenced to a high degree by other factors.

-

3.

Independent Causes Quadrant: This section underscores factors that predominantly influence other components but remain relatively uninfluenced. Technological (F1) and Management (F2) are notably characterized here. Their placement accentuates their pivotal role in driving various facets of VL without being significantly influenced in return.

-

4.

Autonomous Causes Quadrant: The factors positioned here, including Ethical (F5), Evaluation (F8), Interface Design (F7), Study Environment (F10), and Learning Capability (F3), suggest a certain degree of operational autonomy. Their interactions with other factors, in terms of influence exerted and received, appear nominal.

The diagram offers a comprehensive, stratified overview of the VL factors, facilitating an understanding of their roles, interdependencies, and significance in the broader VL landscape.

5. Discussion

In this discussion section, we examine two distinct methodologies to understand the success factors of VL environments: ISM and the conclusive dependence-driven power diagram. Firstly, we explore ISM's approach to identifying hierarchical relationships among VL success factors. Following this, we investigate the conclusive dependence–driving power diagram's method of categorizing factors based on their influence and dependency relationships. Subsequently, we conduct a comparative analysis between ISM and the conclusive dependence–driving power diagram, highlighting their strengths and limitations. Finally, we discuss the contributions of this study and propose avenues for further research in the field of VL.

5.1. ISM of VL success factors

The hierarchical representation of the VL ecosystem, as revealed through the ISM, provides profound insights into the multifaceted dynamics of VL. Each strategically organized level reflects the layered intricacies inherent in the digital educational domain.

Level I, represented solely by Evaluation (F8), accentuates its overarching significance. The dominant position indicates that evaluation methods, including feedback processes and assessment criteria, are central to the VL experience. Their role as primary drivers underscores the need for robust, agile evaluation techniques aptly suited for digital pedagogies. Future research might further delve into optimizing these metrics to enhance digital course outcomes.

The combination of factors at Level II, which include Pedagogical (F4), Ethical (F5), Resource Support (F6), and Institutional (F9) Aspects, highlights the interconnected nature of these elements. Institutions aiming for an enhanced VL experience must ensure seamless integration. The alignment of pedagogical strategies with ethical standards emerges as a crucial area, hinting at the symbiotic relationship between instructional design and integrity in digital platforms.

At Level III, Learning Capability (F3) and Interface Design (F7) come into focus, emphasizing the learner's central role in the process. The alignment between the learner's capabilities and the platform's interface can dictate the effectiveness of the learning process. Consequently, the design of virtual platforms should be intuitive, accommodating the diverse capabilities of the learner base. As technology evolves, user experience optimization for various demographics becomes imperative.

The solitary Study Environment (F10) at Level IV brings attention to the ambient prerequisites of VL. Beyond the digital interface, learners' physical and psychological environment plays a pivotal role. A conducive environment bolsters concentration, engagement, and retention. This aspect beckons further exploration, especially in diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts.

Finally, Level V, characterized by Technological (F1) and Management (F2), is the foundation. The interplay between technology advancements and effective management becomes increasingly crucial as the VL domain expands. Ensuring that technology remains inclusive, adaptive, and scalable, managed with strategic foresight, becomes paramount.

The component in question is shaped by all underlying elements within the ISM model related to the success factors of VL. Both technological and interpersonal aspects influence organizational variables [48], [66]. VL's success hinges on the interplay between technology and human variables, impacting learners' educational experiences. This includes the instructors' ability to manage teaching, the technological readiness, and the students' environment [22]. With all three stakeholders involved, this component is the most critical for VL success. The ISM model offers a structured lens to dissect the VL realm. It stands as a testament to the intricate weave of factors, prompting stakeholders to consider these dynamics for an optimized VL experience holistically. Future explorations might delve deeper into each level's sub-dynamics, fostering a more enriched understanding and paving the way for enhanced virtual educational methodologies.

5.2. Conclusive dependence–driving power diagram

The effect and importance of crucial components in our study are graphically represented by the dependence-driving power diagram. Each factor occupies a distinct category within this representation. As depicted in Fig. 5, the Independent Causes category consists of factors like Technological (F1) and Management (F2) with intense driving but low dependence power. They play a pivotal role in the success of other factors and are instrumental in the triumph of VL teaching and learning [73]. Interestingly, no factor belongs to the Linkage Causes group, suggesting that no factor operates in isolation. Each one influences and is influenced by others, necessitating mindful management.

The third group, Dependent Causes, encompasses factors like Pedagogical (F4), Resource Support (F6), and Institutional (F9). While they possess low driving power, their dependence is substantial. They are governed by various elements such as course management, teaching strategy, technology support, and student engagement. These factors engage all stakeholders, with technology being a key enabler of VL learning [30], [46], [104].

Lastly, the Autonomous Causes are self-reliant with a limited influence on others. However, it is notable that Evaluation (F8) has a lesser driving and dependence force among them. Factors like Ethical (F5), Learning Capability (F3), Interface design (F7), and Study Environment (F10) can critically influence the broader teaching and learning model.

5.3. Analyzing ISM versus conclusive dependence–driving power diagram

Based on the findings obtained from the ISM analysis and the correlation diagram, it is evident that these results exhibit concurrence on the fusion of factors and the interrelationships among them. The concordance between ISM and the abridged visual representation may be depicted in the following manner.

Initially, the two factors listed at the fifth level in the ISM can be viewed as causal relationship agents with significant driving capabilities, although with limited mutual dependence. These factors contribute significantly to enhancing the effectiveness of VL in both teaching and learning environments. This implies that multiple facets are conducive to successful VL management. This finding is consistent with previous research on the success factors of E-learning. Learners need appropriate technology and equipment to access and use online learning resources. Including the learning environment has a stable internet connection. The teachers and technology infrastructure supporting VL are managed [48], [105].

The factors included in Levels III and IV of the ISM are autonomous causal agents. These three factors are mutually interdependent and equally contribute to driving the system. They are influenced by fundamental causes and exert considerable influence over the entire system. The diagram illustrates how this cluster of elements delineates learners' capabilities through the impact of the learning environment and the design of the instructor's interface to facilitate successful learning. These three components all contribute to the same level of success as the first group. Instructors and learners are the two main stakeholders who must drive VL's success. Success depends on the design of the classroom interface and instructional materials. An additional factor to consider is that the instructors method of instruction will be in sync with the abilities of the learners and their environment [91], [99], [106].

Factors located at Level II of the ISM are causal members of the dependence–driving power diagram. Their driving forces are weak, and they rely heavily on other factors. The success of VL is moderately influenced by the support received from educational agencies and relevant officials, as well as the adherence of instructors to teaching principles and ethics. Hence, we possess a high level of confidence in the efficacy of our approach for facilitating the strategic development of future virtual teaching modalities [83].

Evaluation stands as an autonomous causal factor, signifying that the assessment is a factor that directly influences the achievement of VL, irrespective of other factors like course management or learning technology. Effective assessment additionally enables instructors to accurately gauge student progress and enhance their teaching [107].

5.4. Contribution and further work

This work contributes by identifying ten crucial success factors for VL and examining their relationships using the ISM and fuzzy MICMAC. These findings provide valuable insights for improving VL environments and guiding teaching strategies. Additionally, the study emphasizes collaboration among stakeholders and sets a basis for further research in the field of VL.

While this study offers a valuable model for comprehending essential VL factors through the ISM methodology, it does exhibit noteworthy limitations. One major constraint lies in its heavy reliance on expert validation, which may only partially capture a broader VL audience's varied and intricate experiences. Experts' perspectives can be influenced by their backgrounds, introducing potential bias and limiting their view of the VL landscape. Additionally, experts may unintentionally overlook grassroots challenges learners and instructors face in diverse VL settings. Future studies should include a wider range of viewpoints, especially from people who are actively involved in VL, to address these limitations and develop a more complex understanding of the variables influencing VL's efficacy.

Furthermore, validating these factors through methodologies like SEM could represent a significant stride forward, offering a more robust foundation for subsequent academic research and practical applications. Additionally, this model serves as an initial understanding of the factors in the field. However, adapting it for real-world applications will require further development of a VL framework that can be readily applied in practical settings.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study delved into the transformative shifts required within VL models, emphasizing their growing prominence in contemporary education. As educational landscapes pivot to distance learning, understanding the intricacies of VL becomes paramount. We aimed to unravel the nexus between VL's success factors, grounded in a comprehensive literature review and further reinforced through expert validation. Utilizing methodologies like CVI, ISM, and fuzzy MICMAC, we validated and ranked ten pivotal factors across five stratified levels. Foremost, technology and management emerged as cornerstone factors from the fifth level, asserting their influence over VL outcomes. Progressing to the fourth level, these cornerstones influence the learning environment, solidifying its importance in curating conducive VL experiences. The third level delineates factors concerning learning capabilities and interface design, which cascade their influence onto the second level's quartet: institutional support, resource allocation, pedagogical strategies, and ethics. These interconnected factors underscore the role of educators and infrastructural backing in championing VL success. Interestingly, while influential, evaluation maintains a distinct identity, signifying its decisive role in VL achievement. These insights provide a blueprint for the construction of future VL instructional frameworks. The knowledge paves the way for exploring avant-garde teaching techniques across curricula, spurring debates on the comparative merits of diverse learning avenues and their sustainability.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional review board statement

The research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and granted approval by Mahidol University's Ethics Committee (protocol code MU-CIRB 2022/275.1710, November 17, 2022).

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors utilized grammarly.com to edit their work's grammar while it was being prepared. The writers assume full responsibility for the publication's content and have reviewed and edited it as necessary after utilizing this tool or service.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Petai Chuaphun: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Taweesak Samanchuen: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28100.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

This is a two-phase questionnaire designed to investigate the success factors of VL. Based on expert feedback, the first phase validates crucial factors through the CVI. The second phase examines the connections between critical factors using the Delphi method to deepen our understanding of effective VL.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Z. Mseleku, A literature review of E-learning and E-teaching in the era of Covid-19 pandemic, 2020.

- 2.Ulanday M.L., Centeno Z.J., Bayla M.C., Callanta J., et al. Flexible learning adaptabilities in the new normal: e-learning resources, digital meeting platforms, online learning systems and learning engagement. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2021;16 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abakumova I., Zvezdina G., Grishina A., Zvezdina E., Dyakova E. vol. 210. EDP Sciences; 2020. University students' attitude to distance learning in situation of uncertainty; p. 18017. (E3S Web of Conferences). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passerini K., Granger M.J. A developmental model for distance learning using the internet. Comput. Educ. 2000;34:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kentnor H.E. Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States. Curric. Teach. Dial. 2015;17:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keaton W., Gilbert A. Successful online learning: what does learner interaction with peers, instructors and parents look like? J. Online Learn. Res. 2020;6:129–154. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Rawashdeh A.Z., Mohammed E.Y., Al Arab A.R., Alara M., Al-Rawashdeh B. Advantages and disadvantages of using e-learning in university education: analyzing students' perspectives. Electron. J. E-learn. 2021;19:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albrahim F.A. Online teaching skills and competencies. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2020;19:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuhanna I., Alexander A., Kachik A. Advantages and disadvantages of online learning. J. Educ. Verkenn. 2020;1:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firmansyah R., Putri D.M., Wicaksono M.G.S., Putri S.F., Widianto A.A. 2nd Annual Management, Business and Economic Conference (AMBEC 2020) Atlantis Press; 2021. The university students' perspectives on the advantages and disadvantages of online learning due to Covid-19; pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar]