Abstract

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) and body cavity-based lymphomas (BCBLs). The HHV-8 genome is primarily in a latent state in BCBL-derived cell lines like BCBL-1, but lytic replication can be induced by phorbol esters (R. Renne, W. Zhang, B. Herndier, M. McGrath, N. Abbey, D. Kedes, and D. E. Ganem, Nat. Med. 2:342–346, 1996). A 35- to 37-kDa glycoprotein (gp35-37) is the polypeptide most frequently and intensively recognized by KS patient sera on Western blots with induced BCBL-1 cells. Its apparent molecular mass is reduced to 30 kDa by digestion with peptide-N-glycosidase F. By searching the known HHV-8 genomic sequence for open reading frames (ORF) with the potential to encode such a glycoprotein, an additional, HHV-8-specific reading frame was identified adjacently to ORF K8. This ORF, termed K8.1, was found to be transcribed primarily into a spliced mRNA encoding a glycoprotein of 228 amino acids. Recombinant K8.1 was regularly recognized by KS patient sera in Western blots, and immunoaffinity-purified antibodies to recombinant K8.1 reacted with gp35-37. This shows that the immunogenic gp35-37 is encoded by HHV-8 reading frame K8.1, which will be a useful tool for studies of HHV-8 epidemiology and pathogenesis.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a multifocal, proliferative lesion of uncertain pathogenesis. The originally described form occurs sporadically in elderly men of eastern- or southern-European descent. The frequent occurrence of KS in young homosexual patients has been one of the first hallmarks of the AIDS epidemic. From the very beginning, the epidemiology of KS among AIDS patients has suggested that an infectious agent other than human immunodeficiency virus is involved in KS pathogenesis (6, 15). This led to a broad search in patients with KS for both known and new transmissible human pathogens. A new era of KS research began when Chang et al. (11) detected DNA sequences of a novel herpesvirus in KS tissues of AIDS patients. Meanwhile, DNA of this virus, now termed human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) or KS-associated herpesvirus, has been found in all epidemiological forms of KS (1, 12, 14, 19, 24). In addition to KS, HHV-8 DNA has also been found in certain forms of Castleman’s disease (33) and in AIDS-associated body cavity-based lymphomas (BCBL) (9, 10). Cell lines established from BCBL harboring the HHV-8 genome facilitated first studies of HHV-8 seroepidemiology. By using nonstimulated BCBL-derived cells, antibodies against latent nuclear antigens (LNA) of HHV-8 were found in 70 to 80% of AIDS-KS patients (17, 20, 25). In the United States and northern Europe, anti-LNA seropositivity has been found to closely reflect the risk of KS development. Only 1% of adult blood donors were anti-LNA positive. Likewise, only 1 to 3% of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected hemophiliacs were found to be anti-LNA positive, whereas 35% of HIV-infected homosexual patients had detectable levels of antibodies against LNA (20). In contrast to northern Europe and the United States, 84 to 100% of the general population have been found to be HHV-8 anti-LNA positive in several African countries (16, 21). KS is known to be endemic in several areas of sub-Saharan Africa. However, as noted by Gompels and Kasolo (18), the high seroprevalence of HHV-8 in Africa is not limited to areas of high KS incidence. Whereas only 70 to 80% of Caucasian AIDS-KS patients had antibodies detectable with HHV-8 LNA, Lennette et al. were able to detect HHV-8 antibodies in 100% of KS patients when they included HHV-8 lytic antigens that are expressed after phorbol ester induction of BCBL-1 cells (21). Surprisingly, 24% of healthy adults were HHV-8 positive by this assay. Although HHV-8 seropositivity still correlates with risk of KS in this assay, a seroprevalence of 24% in the general population would not allow for the currently favored dual-factor scenario of KS pathogenesis, where HHV-8 is the relatively infrequent, sexually transmitted determinant of KS in conjunction with immunosuppression and/or genetic predisposition. The immunofluorescence assay based on both lytic and latent antigens of HHV-8 is likely to be more sensitive than the LNA assay, but it may well be compromised by reduced specificity. A reliable evaluation of the pathogenic role of HHV-8 in KS, BCBL, Castleman’s disease, and multiple myeloma (31) will not be possible until a serologic assay is available that is both sensitive and specific. This calls for mapping HHV-8 lytic antigens of immunologic relevance and characterization of non-cross-reactive epitopes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

Sera were collected from patients at hospitals and outpatient departments of the University of Erlangen. All sera were stored at −20°C and heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min prior to use.

Cell culture.

Suspension cultures of HHV-8 carrying BCBL-1 (30) and BC-3 (5) cells, as well as the HHV-8-negative Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line BJAB, were maintained at 37°C with 7.5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 mg of gentamicin per ml, and 350 mg of l-glutamine per ml. Expression of viral genes in BCBL-1 and BC-3 cells was stimulated with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA; Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) at 25 ng/ml for 4 days.

Endoglycosidase digestion of glycoproteins.

Peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) was obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), and protein lysate from BCBL-1 cells was digested as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, BCBL-1 cells were lysed in 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–2% β-mercaptoethanol at 95°C for 10 min, followed by digestion of 400 μg of protein with 150 International Union of Biochemistry (IUB) mU PNGase F (1 IUB mU = 65 New England Biolabs U) for 2 h at 37°C in 150 μl of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5)–1% Nonidet P-40.

Western blot analysis.

TPA-stimulated and nonstimulated BCBL-1 and BJAB cells were harvested by centrifugation (10 min, 400 × g), washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in 2× SDS sample buffer (4% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 120 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 0.1 mg bromphenol blue per ml). An equivalent of 105 cells was separated per lane on discontinuous SDS–12 and 15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels containing methylenebisacrylamide and acrylamide at a ratio of 1:29. Western blot analyses were carried out as described previously (28). Briefly, proteins were transferred from discontinuous SDS–12 and 15% polyacrylamide gels onto nitrocellulose membranes by using the Hoefer SemiPhor TE70 blotting apparatus as described by the manufacturer (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The membranes were first blocked for 2 h at 20°C in blocking buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween, 5% low-fat milk) and then incubated for 2 h with human sera diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer, followed by three washes in TBS-Tween (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween) and 1 h of incubation with rabbit anti-human immunoglobulin G alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Dako Diagnostika GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). After two washes in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-Tween, in TBS, and in H2O, membranes were stained with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyphosphate toluidinium (salt) RAD-free tablets as recommended by the supplier (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Dassel, Germany). All steps were carried out at room temperature.

RT-PCR and DNA sequencing.

Total RNA was extracted from BCBL-1 cells both prior to and following stimulation with TPA by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (13). For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), Superscript mouse mammary tumor virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco/BRL) and the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) were used essentially as specified in the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, reverse transcription of 0.5 μg of total RNA was performed at 50°C for 30 min in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 μM (each) primers K8.1-B1 (GAT CGG ATC CTA ACC ATG AGT TCC ACA CAG ATT C) and K8.1-X1 (GAT CTC TAG AGG TTT TGT GTT ACA CTA TGT AGG), 0.5 μl of Superscript, and 0.5 μl of Expand high-fidelity polymerase, an enzyme mix containing thermostable Taq DNA and Pwo DNA polymerase. Subsequently, the above reaction mixture was heated to 94°C for 2 min, and cDNA was amplified by 35 cycles (94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 45 s). From the 11th cycle on, the time of the elongation reaction (68°C) was increased by 5 s/cycle. Control reactions were performed without Superscript reverse transcriptase. Amplified DNA was separated on 1% agarose gels, and the PCR products were purified by the Qia-EX method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Purified RT-PCR products were sequenced with primers K8.1rt-5′ and K8.1rt-3′ and dye terminator chemistry on an ABI-377A sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Expression of recombinant proteins.

Reading frames ORF47, vIL-6, and K8.1 were amplified from genomic DNA without the sequences coding for the predicted N-terminal signal peptide. Primer pairs were H8-47bam (GAT TGG ATC CAT GGG GAT CTT TGC GCT ATT TG) and H8-47Hind (GAT CAA GCT TGC AAC CAT GCG TCC ATG TTG AAC) for ORF47, K8.1mBam (GTG CGG ATC CAA TTG TCC CAC GTA TCG TTC) and K8.1HindR (GGC AAA GCT TGG CAC ACG GTT ACT AGC ACC) for K8.1, and vIL6-5H-Bam (AGC TGG ATC CAA GTT GCC GGA CGC CCC CGA GTT TG) and vIL6-3-Hind (AGC TAA GCT TAT CGT GGA CGT CAG GAG TCA C) for vIL-6 (K2). The complete HHV-8 reading frame K1 was expressed as three overlapping fragments: K1-N (N terminus), K1-M (middle), and K1-C (C terminus). Primer pairs K1-Bam3 (GAT GGA TCC ATG TCC CTG TAT GTT GTT TGC)-Klr-NHind (GGT TAA GCT TCG TCC GTT TGG TAG ATG C), H8K1-MBam (ATA TGG ATC CCC TGT CTT ACA AAC CTT GTG)-H8K1r-MHind (TAT TAA GCT TCC TAT CAG AGC TAC GAG TG), and H8K1-CBam (ATA TGG ATC CAC TCA TAC TGT ATC TGT CAG C)-K1-hindR3 (GAT CAA GCT TAC CTG AAT GTC AGT ACC) were used to amplify inserts for pQK1N, pQK1M, and pQK1C, respectively. PCR products were cloned into the prokaryotic expression vector pQE9 (Quiagen Inc.) via BamHI and HindIII restriction sites (underlined). The resulting expression plasmids encode an N-terminal tag containing six histidine residues (MRGSHHHHHHGS). Recombinant proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli JM109 or M15prep4 and purified under denaturing conditions according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quiagen Inc.). Briefly, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to E. coli cultures to a final concentration of 2 mM at mid-log phase, and the bacteria were incubated for another 1 to 3 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g and lysed in 6 M guanidinum rhodanide–10 mM Tris (pH 8.0). The cleared lysate was applied immediately to an Ni-nitrolotriacetic acid resin column (Quiagen Inc.). The column was rinsed with 5 volumes of wash buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.3]). Wash buffer containing increasing amounts of imidazole (10 mm to 400 mM) was applied to the column to elute recombinant protein. Collected fractions were checked for the presence of recombinant protein by electrophoretic separation on 15% polyacrylamide gels followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Purified recombinant proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES (pH 8.0)–1 mM MgCl2–20 mM KCl–0.5 mM dithiothreitol–0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride–0.1 mM EDTA–10% glycerol, and the concentration of protein was determined by the colorimetric bicinchoninic acid assay as described by the manufacturer (Pierce Inc., Rockford, Ill.). Amino acids 2 to 170 of HHV-8 ORF65 were expressed as gluthatione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. To generate the expression constructs, primers GAG AGA GAT CTG TTC CAA CTT TAA GGT GAG AGA C and TCT GCA TGC CGG TTG TCC AAT CGT TGC CTA (32) were used. The amplified fragment was ligated into expression vector pGEX-3X (Amersham Pharmacia-Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and purified on gluthatione-Sepharose 4B as instructed by the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia-Biotech).

Generation of rabbit antiserum.

Recombinant K8.1β was first affinity purified by Ni-chelate chromatography followed by separation on preparative SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining, and the area containing K8.1β was excised from the gel and homogenized. Male New Zealand White rabbits were immunized intramuscularly with a suspension of homogenized polyacrylamide in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant containing 200 μg of recombinant protein. Rabbits were boosted three times at 2-week intervals with the same amount of protein and bled 7 days after the last injection.

Affinity purification of antibodies.

Recombinant K8.1γ (200 μg) was separated on preparative SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels. After transfer onto a nitrocellulose membrane the recombinant protein was visualized by Ponceau red staining and excised. The excised nitrocellulose strip containing recombinant protein was blocked with 5% low-fat milk–TBS and incubated with KS patient serum as described above. The nitrocellulose was washed extensively in TBS-Tween, and antibodies were eluted with 100 mM glycine (pH 3.0), neutralized immediately with 1 M Tris (pH 8.0). The affinity-purified antibodies were stabilized by sodium azide until use.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequences presented here have been given GenBank accession no. AF009173.

RESULTS

A glycoprotein of 35 to 37 kDa is regularly recognized by KS patient sera.

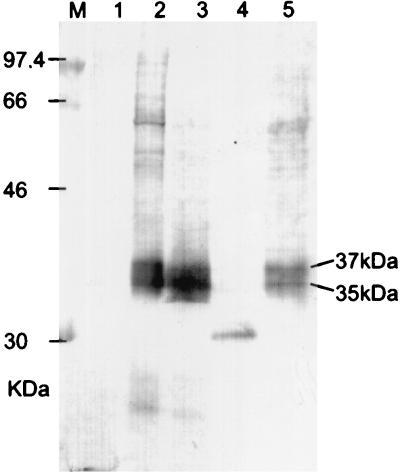

Sera from HIV-negative and HIV-positive KS patients were collected at the Erlangen University hospital. To identify immunoreactive viral polypeptides, reactivities of KS patient sera with HHV-8 antigens were characterized by Western blot using TPA-stimulated BCBL-1 cells. Five examples of the staining pattern typically observed with HIV-positive KS patient sera are shown in Fig. 1 and 2. All five sera clearly reacted with HHV-8-infected BCBL-1 cells (lanes 2), whereas no reactivity was seen with proteins from the HHV-8-negative human B-cell line BJAB (lanes 1). Although the sera shown in Fig. 1 and 2 certainly reacted with several proteins of TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells, a BCBL-1 cell protein of 35- to 37-kDa was most frequently and strongly recognized (lanes 2 in Fig. 1 and 2). Seventeen of 19 HIV-positive KS patient sera and two sera from classical-KS patients were clearly reactive with the 35- to 37-kDa protein, whereas no reactivity was seen with the majority of 50 blood donor sera (Table 1). More focused bands of 11 kDa (Fig. 2, sera B and C), 18 kDa (Fig. 1), 36 kDa (Fig. 2, serum C) and about 55 kDa (Fig. 2, serum C) were seen less frequently. As blurred appearance is often indicative of protein glycosylation, BCBL-1 cell proteins were subjected to PNGase F digestion prior to electrophoresis. Proteolysis was not detected when PNGase F-digested proteins were checked by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). When deglycosylated proteins were used for Western blots with KS patient sera, the blurred 35- to 37-kDa antigen disappeared and a sharply focused antigen of 30 kDa was recognized instead, albeit with reduced reactivity (Fig. 1, lane 4). Expression of gp35-37 was clearly inducible by TPA (Fig. 1, lane 2), although lower levels of gp35-37 are expressed in BCBL-1 cells prior to induction with TPA (Fig. 1, lane 5). This is in good agreement with the finding that 2 to 5% of BCBL-1 cells enter the lytic cycle spontaneously, and the percentage of cells expressing lytic antigens can be increased three- to fivefold by TPA induction (30).

FIG. 1.

Reactivity of an AIDS KS patient serum with a glycosylated BCBL-1 cell protein. The patient serum was tested at a dilution of 1/200. Lane M, molecular weight marker; lane 1, BJAB cells; lanes 2 to 4, BCBL-1 cells induced with TPA (25 ng/ml, 4 days); lane 5, uninduced BCBL-1 cells. BCBL-1 cells in lanes 3 and 4 were mock digested and digested with PNGase F, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Reactivities of four AIDS-KS patient sera (A to D) with BCBL-1 cell proteins and recombinant HHV-8 proteins. All four sera clearly reacted with gp35-37 in BCBL-1 cells and recombinant K8.1. In addition, there is reactivity with proteins of about 50 kDa (serum C), 11 kDa (sera A and C), and 18 kDa (serum C), as well as p18-GST (serum C). Lanes 1, BJAB cells; lanes 2, BCBL-1 cells; lanes 3, recombinant K8.1γ; lanes 4, p18 (ORF65)-GST fusion protein; lanes 5: recombinant viral IL-6.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities of human sera with HHV-8 proteins in Western blotsa

| Group | BCBL-1 gp35-37 | rK8.1 | rvIL-6 | GST-p18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+/KS+ | 17/19 | 17/19 | 2/19 | 10/19 |

| Classical KS | 2/2 | 2/2 | 0/2 | NT |

| Blood donors | 2/18 | 2/50 | 0/50 | 2/50 |

| EBV primary infection | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 2/10 |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | NT | 0/9 | NT | 0/9 |

All sera were tested at a dilution of 1/50. HIV+/KS+, AIDS-associated KS; classical KS, KS without HIV infection; EBV primary infection, clinically diagnosed and serologically confirmed infectious mononucleosis; BCBL-1 gp35-37, reactivity with the 35- to 37-kDa glycoprotein in TPA-stimulated BCBL-1 cells; rK8.1, procaryotically expressed recombinant K8.1γ or K8.1β; rvIL-6: recombinant HHV-8 IL-6; GST-p18, HHV-8 ORF65 expressed as a GST fusion protein. The two blood donor sera positive for rK8.1 (confirmed by Western blot on BCBL-1 cells) were not identical with the blood donor sera positive for GST-p18. Only 18 blood donor sera were tested by Western blot on BCBL-1 cells. NT, not tested.

Identification of putative glycoprotein genes in the HHV-8 genomic sequence.

Sequence analysis methods were used to identify HHV-8 genes with the potential to encode a glycoprotein of 35 to 37 kDa. First, the HHV-8 genomic sequence derived from a KS biopsy specimen (26, 27) was searched for open reading frames presumably encoding a polypeptide with a calculated molecular mass ranging from 15 to 40 kDa. A total of 32 open reading frames was selected of which two, K8.1 and K10.1, had not been identified before. Next, the putative amino acid sequences were screened for the presence of consensus sequences for N-linked glycosylation (Asn-X-[Ser/Thr]). Peptides with such putative N-glycosylation sites were analyzed for the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide by the method of Nielsen et al. (29). Only HHV-8 open reading frames ORF47 (18 kDa), K8.1 (21.8 kDa), viral IL-6 (23.4 kDa), and K1 (30.4 kDa) met all three criteria.

Two spliced mRNAs are transcribed from the K8.1 locus of HHV-8.

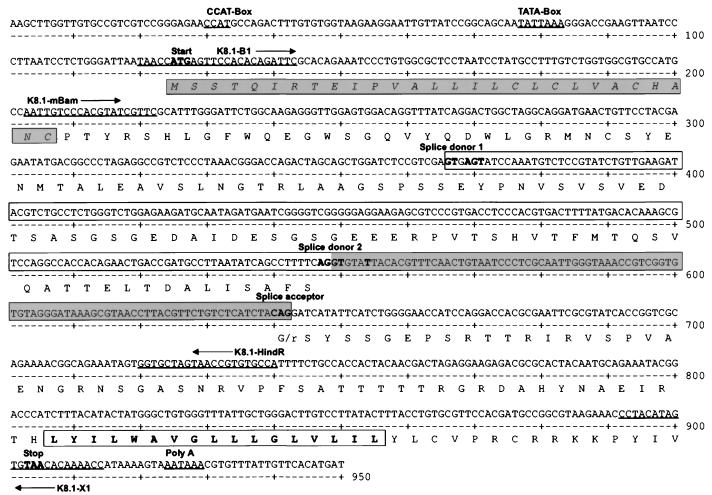

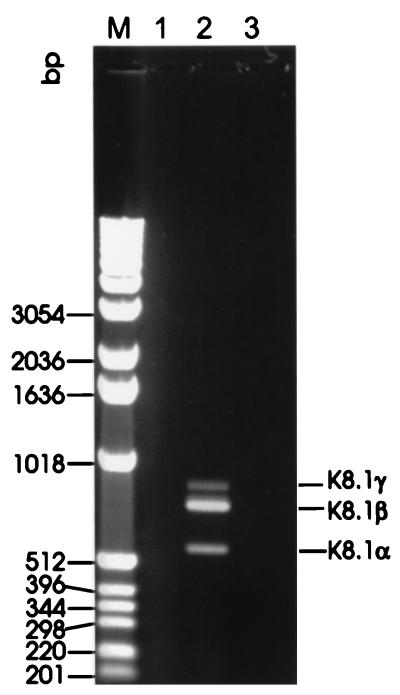

Open reading frame K8.1 is located between open reading frames K8 and ORF52 of HHV-8. With respect to its relative position in the genome, K8.1 is therefore similar to ORF51 of herpesvirus saimiri (2), M7 of murine herpesvirus 68 (37), BORFD1 of bovine herpesvirus 4 (BHV-4) (22), and gp220/350 of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). These genes invariably encode transmembrane glycoproteins that have been shown to be translated from a spliced message whenever examined. RT-PCR was performed with RNA extracted from TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells, uninduced BCBL-1 cells, and the HHV-8-negative human B-cell line BJAB by using primer K8.1-B1, located close to the 5′ end, and primer K8.1-X1, which binds immediately upstream of a putative polyadenylation site (Fig. 3). Amplification of HHV-8 genomic DNA with these primers yields a fragment of 815 nucleotides. However, in addition to a fragment the size of an unspliced message, termed K8.1γ, two fragments of about 720 and 540 nucleotides were amplified by RT-PCR from RNA extracted from TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells (Fig. 4). The latter fragments were designated K8.1β and K8.1α, in Fig. 4, respectively, with K8.1β being clearly the most abundant message. As shown in Fig. 4, none of the three fragments could be amplified without prior reverse transcription (lane 1). Direct sequencing of all three amplicons (K8.1γ, K8.1β, and K8.1α) showed that K8.1γ is an unspliced RNA, whereas K8.1α and K8.1β correspond to two singly spliced messages (Fig. 3). K8.1α and K8.1β messages have the same 3′ exon. It encodes a putative transmembrane region and, like the positional analogous glycoproteins of other rhadinoviruses, is relatively rich in serine and threonine (Fig. 3). The calculated molecular masses of proteins translated from K8.1β and K8.1α are 24.8 and 18.6 kDa, respectively. They are reduced to 21.8 and 15.6 kDa if the predicted signal peptide (amino acids 1 to 28 [Fig. 3]) is omitted. The calculated molecular mass of a protein possibly translated from the unspliced K8.1γ message would be 21.8 or 18.8 kDa after cleavage of the 28-amino-acid signal peptide.

FIG. 3.

Map of reading frame K8.1. The amino acid sequence is shown in single-letter code below the nucleotide sequence. Nucleotides matching the splice donor (A64 G73 G100 T100 A62 A68 G84 T63) or splice acceptor (C65 A100 G100) consensus sequence are boldfaced. Putative CAT (CCAT) and TATA (TATTAAA) boxes are indicated, as are the oligonucleotides (K8.1-B1, K8.1-X1, K8-1mBam, K8.1-HindR) used for RT-PCR and sequencing. The predicted N-terminal signal peptide is italicized and shaded; the intron of K8.1α is boxed between splice donor 1 and the common splice acceptor. The nucleotide sequence corresponding to the intron of K8.1β is shaded. The amino acid sequence of the predicted transmembrane region of K8.1α and K8.1β is boldfaced and boxed. The C-terminal amino acid sequence of the nonspliced putative K8.1γ is not shown.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR of reading frame K8.1. using DNase I-digested RNA extracted from TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells. Three fragments can be amplified by reverse transcription and are not detectable without reverse transcription. The size of K8.1γ is in agreement with the size expected for an unspliced transcript (815 bp). Primers K8.1-B1 and K8.1-X1 (Fig. 3) were used. Lane M, molecular weight marker (kb ladder; Gibco BRL); lane 1, PCR without reverse transcription; lane 2, RT-PCR; lane 3, H2O control RT-PCR.

The procaryotically expressed first exon of K8.1 is regularly recognized by KS patient sera.

Reading frames ORF47 (encoding the HHV-8 homolog of glycoprotein L), viral IL-6, and K8.1γ were amplified from genomic DNA without sequences coding for the predicted N-terminal signal peptides. Sequences coding for K8.1β were amplified from cDNA by using primers K8.1mBam and K8.1-X1. The recombinant proteins (200 ng each) were used to assess reactivity with human sera in immunoblot assays. Sera that had been found to be reactive with native gp35-37 were tested at a dilution of 1:200. Both K8.1β and K8.1γ reacted with all 17 sera (Table 1). Reactivity with any of the other recombinant proteins was seen much less frequently (Fig. 2, lanes 3 to 5, and Table 1). Further testing of KS and non-KS sera confirmed the suitability of K8.1 for serologic assays: 17 of 19 KS patient sera clearly reacted with recombinant K8.1 (both β and γ). Most notably, all sera that recognized gp35-37 in TPA-stimulated BCBL-1 cells also reacted with recombinant K8.1. Likewise, the two KS patient sera that did not recognize recombinant K8.1 were also negative for antibodies against native gp35-37. Two of the KS sera that were positive for gp35-37 also showed moderate reactivity with recombinant viral IL-6. None of the sera tested reacted with recombinant ORF47 protein (Table 1). Similarly, antibodies against recombinant viral IL-6 or recombinant ORF47 were not detectable in any of 50 blood donor sera, two of which reacted with recombinant K8.1. Two additional sera reacted with HHV-8 ORF65 expressed as GST fusion protein (GST-p18). Recombinant K8.1 did not react with nine sera from Chinese nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients (Table 1). It was also not reactive with 10 sera from serologically proven primary EBV infection which also did not recognize gp35-37 in BCBL-1 cells. Thus, K8.1 is not cross-reactive with EBV, as can be expected from the lack of detectable sequence conservation. In contrast, recombinant HHV-8 ORF65 protein did show moderate reactivity with 2 of the 10 sera from patients with primary EBV infection, pointing to a possible cross-reactivity of ORF65 with its homolog in EBV, the immunogenic protein p40. HHV-8 ORF65 has already been reported to encode an HHV-8 lytic antigen of 18 kDa (p18) (32) and is currently used for serological testing (8). Ten of the 19 sera from HIV-positive KS patients tested here were reactive with recombinant ORF65; all of them also reacted with recombinant K8.1. Antibodies directed against HHV-8 ORF65 protein have been reported to be specific for HHV-8 (32), and none of the nine highly EBV-reactive nasopharyngeal carcinoma patient sera tested here showed reactivity with ORF65 (Table 1). However, antibodies produced early in the course of a natural infection often exhibit reduced affinity and specificity, and this may explain the low reactivities of two sera from patients with primary EBV infection to recombinant ORF65 of HHV-8. All sera were tested with both recombinant K8.1γ and recombinant K8.1β, and reactivities were found to be identical. As recombinant K8.1γ and K8.1β share only amino acids 28 to 108 of the K8.1 protein, the immunogenic epitopes of HHV-8 K8.1 must be located within the first exon.

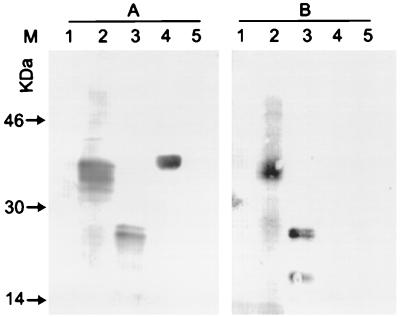

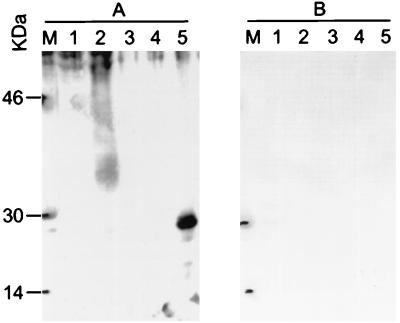

The immunogenic glycoprotein gp35-37 of HHV-8 is encoded by K8.1.

K8.1-specific antibodies were affinity purified from KS patient serum. An immunoblot of unabsorbed serum from an AIDS-KS patient is shown in Fig. 5A. The serum clearly recognized gp35-37 in whole BCBL-1 cells. It also reacted with recombinant K8.1γ and recombinant ORF65-GST fusion protein. As can be seen in Fig. 5B, antibodies affinity purified with recombinant K8.1γ also reacted with both cellular gp35-37 and recombinant K8.1; however, no reactivity was seen with other recombinant HHV-8 proteins. It is thus concluded that gp35-37 is encoded by HHV-8 reading frame K8.1. To show more directly that the immunogenic glycoprotein gp35-37 is encoded by the HHV-8 gene K8.1, a rabbit serum was raised against recombinant K8.1β. At a dilution of 1:200, the rabbit serum clearly recognized recombinant K8.1β (Fig. 6A, lane 5) and gp35-37 in TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells (Fig. 6A, lane 2). However, no reactivity was seen with either the protein from BJAB cells or recombinant human IL-6 (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 4). Thus, at least three lines of evidence indicate that gp35-37 is in fact encoded by K8.1. Antibodies absorbed from human serum with recombinant K8.1 show the characteristic staining pattern, as does an antiserum raised against recombinant K8.1. In addition, all sera that did react with BCBL-1 gp35-37 also reacted with recombinant K8.1β, and sera that were not reactive to recombinant K8.1 also did not show the characteristic gp35-37 reactivity. In SDS-polyacrylamide gels, recombinant K8.1γ migrates with an apparent molecular mass of 26 kDa (Fig. 5, lanes 3), and K8.1β migrates with an apparent molecular mass of 30 kDa (Fig. 6A, lane 5). The latter is in good agreement with the apparent molecular weight observed for deglycosylated gp35-37 (Fig. 1, lane 4). Most likely, the 35- to 37-kDa protein is translated from the K8.1β transcript.

FIG. 5.

Western blot of anti-K8.1 antibodies affinity purified from an AIDS-KS patient serum. (A) Whole serum; (B) K8.1γ affinity-purified antibodies. The purified antibodies still recognize gp35-57 in BCBL-1 cells as well as recombinant K8.1γ; however, they do not react with GST-p18 (ORF65). Lanes 1, BJAB cells; lanes 2, TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells; lanes 3, recombinant K8.1γ (200 ng); lanes 4, recombinant p18-GST fusion protein (HHV-8 ORF65); lanes 5, recombinant viral IL-6.

FIG. 6.

Reactivity of a rabbit serum raised against recombinant K8.1β. (A) Serum from an immunized rabbit, diluted 1/200; (B) preimmune serum. Serum from the immunized rabbit recognized both recombinant K8.1β and a protein of 35 to 37 kDa in TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells. Lanes 1, BJAB cells; lanes 2, TPA-induced BCBL-1 cells; lanes 3, water; lanes 4, recombinant human IL-6 (200 ng); lanes 5, recombinant K8.1β (200 ng). Lanes M, molecular weight markers.

DISCUSSION

We show that the HHV-8 open reading frame K8.1 identified here encodes an immunogenic, TPA-inducible glycoprotein of HHV-8. This conclusion is based on four findings. First, several features predicted for a protein encoded by reading frame K8.1 are in concordance with the characteristics of gp35-37. Second, all KS patient sera that recognized gp35-37 also reacted with recombinant K8.1, whereas sera that did not react with gp35-37 did not react with recombinant K8.1. Third, antibodies affinity purified from KS patient serum recognized gp35-37 in TPA-stimulated BCBL-1 cells. Fourth, a rabbit serum was raised against recombinant K8.1 which recognized both K8.1 and gp35-37. HHV-8 serologic assays including TPA-inducible antigens have recently been shown to be more sensitive than the more widely used LNA-based assay (21). However, the use of whole cells for Western blot or immunofluorescence assay may be hampered by cross-reactivity of the usually well-conserved structural proteins, as has already been shown for the major capsid proteins of HHV-8 and EBV (4). In addition, we observed reactivity of procaryotically expressed HHV-8 ORF65 (p18) with a few sera from patients with primary EBV infection. The use of purified, HHV-8-specific lytic-cycle antigens generated by chemical synthesis or recombinant expression will increase the sensitivity of current HHV-8 serology without sacrificing specificity. This is certainly of particular importance for studies of HHV-8 seroepidemiology in the general population. HHV-8 antibody titers in healthy adults are likely to be much lower than those in KS patients, where both latent (34, 36) and lytic-cycle antigens are permanently produced (7). When only recombinant K8.1 was used, about 90% (17 of 19) of KS patient sera were clearly HHV-8 seropositive. Cross-reactivity of K8.1 with other herpesvirus proteins is unlikely, as K8.1 is not conserved among known herpesviruses. Accordingly, we did not observe reactivity in sera from patients with EBV primary infection or nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The immunogenic protein encoded by reading frame K8.1 will thus be useful for epidemiological studies. RT-PCR revealed that at least three different mRNAs—K8.1α, K8.1β, and K8.1γ—map to open reading frame K8.1. K8.1β and K8.1α share the same splice acceptor but employ two different donor sites. Both K8.1β and K8.1α are predicted to encode typical transmembrane glycoproteins with a C-terminal membrane anchor and short cytoplasmic tail. In addition, an unspliced message was amplified by RT-PCR in low amounts (K8.1γ). Although we show that this amplicon is not due to contaminating genomic DNA, we cannot exclude the possibility that nuclear pre-mRNA was amplified. It is thus not known whether the corresponding protein is made in a natural infection. If so, K8.1γ could code for a soluble form of K8.1, as the predicted protein would lack a transmembrane anchor. As procaryotically expressed recombinant K8.1γ and K8.1β were equally reactive in immunoblot assays, the immunogenic epitopes of K8.1 must be located within the first exon. HHV-8 K8.1 does not have overt amino acid sequence homology with any sequence currently available in DNA and protein databases. However, a reading frame predicted to encode an apparently nonconserved glycoprotein is present at the same genomic position in all gammaherpesviruses sequenced so far. Thus, the positional analog to HHV-8 K8.1 in herpesvirus saimiri is ORF51. The latter is predicted to encode a nonconserved polypeptide with a calculated relative molecular mass of 30 kDa with an N-terminal signal peptide, a C-terminal transmembrane region, and nine N-linked glycosylation sites (3). The BHV-4 reading frame BORFD1 is the positional analog of K8.1 and ORF51 of HHV-8 and herpesvirus saimiri, respectively. BORFD1 has been predicted to encode a spliced transmembrane glycoprotein of 273 amino acids (22), which has been confirmed by experimental evidence more recently (23). Reading frame M7 is the positional analog of murine herpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) (37). The predicted molecular mass of the core unglycosylated protein encoded by M7 is 48 kDa. However, the corresponding glycoprotein migrates with an apparent molecular mass of 130 to 150 kDa when separated by denaturating PAGE (35). The reading frame BLLF1a/b of EBV shares relative genomic position and orientation with K8.1. It encodes a membrane glycoprotein with a relative molecular mass of 220 to 340 kDa which is known to be involved in binding to host cells via CD21. Like K8.1 of HHV-8 and gp80 of BHV-4, gp340/220 is translated from a spliced message. We thus conclude that proteins encoded by K8.1 (gp35-37; HHV-8), ORF51 (herpesvirus saimiri), BORFD1 (gp80; BHV-4), M7 (gp150; MHV 68), and possibly BLLF1 (gp220/350; EBV) belong to one family of serine- and threonine-rich virion transmembrane glycoproteins. It has been shown that two members of this family, EBV gp340/220 and MHV-68 gp150, are involved in binding to the host cell. The high degree of variability observed within this family of glycoproteins may thus reflect the divergence in cell tropism. Studies are underway in this laboratory to show whether HHV-8 K8.1 is involved in cell attachment or virus entry. Beyond its use for studies of epidemiology, HHV-8 K8.1 might prove useful for studies of HHV-8 target cell recognition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Ria Freifrau von Fritsch Stiftung and Deutsche Krebshilfe-Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung grant W134/94/FL2. A Birkmann was supported by the European Union grant BMH4-CT95-1016.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albini A, Aluigi M G, Benelli R, Berti E, Biberfeld P, Blasig C, Calabro M L, Calvo F, Chieco-Bianchi L, Corbellino M, Del Mistro A, Ekman M, Favero A, Hofschneider P H, Kaaya E, Lebbe C, Morel P, Neipel F, Noonan D M, Parravicini C, Repetto L, Schalling M, Stürzl M, Tschachler E. Oncogenesis in HIV-infection: KSHV and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Int J Oncol. 1996;9:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht J C, Nicholas J, Biller D, Cameron K R, Biesinger B, Newman C, Wittmann S, Craxton M A, Coleman H, Fleckenstein B, Honess R W. Primary structure of the herpesvirus saimiri genome. J Virol. 1992;66:5047–5058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.5047-5058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht J C, Nicholas J, Cameron K R, Newman C, Fleckenstein B, Honess R W. Herpesvirus saimiri has a gene specifying a homologue of the cellular membrane glycoprotein CD59. Virology. 1992;190:527–530. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91247-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andre S, Schatz O, Bogner J R, Zeichhardt H, Stoffler-Meilicke M, Jahn H U, Ullrich R, Sonntag A K, Kehm R, Haas J. Detection of antibodies against viral capsid proteins of human herpesvirus 8 in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Mol Med. 1997;75:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s001090050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvanitakis L, Mesri E A, Nador R G, Said J W, Asch A S, Knowles D M, Cesarman E. Establishment and characterization of a primary effusion (body cavity-based) lymphoma cell line (BC-3) harboring Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) in the absence of Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1996;88:2648–2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beral V, Peterman T A, Berkelman R L, Jaffe H W. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90001-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasig C, Zietz C, Haar B, Neipel F, Esser S, Brockmeyer N H, Tschachler E, Colombini S, Ensoli B, Sturzl M. Monocytes in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions are productively infected by human herpesvirus 8. J Virol. 1997;71:7963–7968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7963-7968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabro M L, Sheldon J, Favero A, Simpson G R, Fiore R, Gomes E, Angarano G, Chieco-Bianchi L, Schulz T F. Seroprevalence of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 in several regions of Italy. J Hum Virol. 1998;1:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore P S, Said J W, Knowles D M. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cesarman E, Moore P S, Rao P H, Inghirami G, Knowles D M, Chang Y. In vitro establishment and characterization of two acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma cell lines (BC-1 and BC-2) containing Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like (KSHV) DNA sequences. Blood. 1995;86:2708–2714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin M S, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles D M, Moore P S. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang Y, Ziegler J, Wabinga H, Katangole Mbidde E, Boshoff C, Schulz T, Whitby D, Maddalena D, Jaffe H W, Weiss R A, Moore P S. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and Kaposi’s sarcoma in Africa. Uganda Kaposi’s Sarcoma Study Group Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:202–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupin N, Grandadam M, Calvez V, Gorin I, Aubin J T, Havard S, Lamy F, Leibowitch M, Huraux J M, Escande J P, et al. Herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in patients with Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:761–762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman Kien A E, Laubenstein L J, Rubinstein P, Buimovici Klein E, Marmor M, Stahl R, Spigland I, Kim K S, Zolla Pazner S. Disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:693–700. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao S J, Kingsley L, Hoover D R, Spira T J, Rinaldo C R, Saah A, Phair J, Detels R P-P, Chang Y, Moore P S. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:233–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607253350403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao S J, Kingsley L, Li M, Zheng W, Parravicini C, Ziegler J, Newton R, Rinaldo C R, Saah A, Phair J, Detels R, Chang Y, Moore P S. KSHV antibodies among Americans, Italians and Ugandans with and without Kaposi’s sarcoma. Nat Med. 1996;2:925–928. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gompels U A, Kasolo F C. HHV-8 serology and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1996;348:1587–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y Q, Li J J, Kaplan M H, Poiesz B, Katabira E, Zhang W C, Feiner D, Friedman Kien A E. Human herpesvirus-like nucleic acid in various forms of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Lancet. 1995;345:759–761. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90641-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedes D, Operalski E, Busch M, Kohn R, Flood J, Ganem D E. The seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus): distribution of infection in KS risk groups and evidence for sexual transmission. Nat Med. 1996;2:918–924. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lennette E T, Blackbourn D J, Levy J A. Antibodies to human herpesvirus type 8 in the general population and in Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. Lancet. 1996;348:858–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomonte P, Bublot M, van Santen V, Keil G M, Pastoret P P, Thiry E. Analysis of bovine herpesvirus 4 genomic regions located outside the conserved gammaherpesvirus gene blocks. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1835–1841. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomonte P, van Santen V, Filée P, Lyaku J R, Bublot M, Thiry E. Identification and characterization of bovine herpesvirus 4 gp80: a new gammaherpesvirus-specific virion glycoprotein. 1997. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchioli C C, Love J L, Abbott L Z, Huang Y Q, Remick S C, Surtento-Reodica N, Hutchison R E, Mildvan D, Friedman Kien A E, Poiesz B J. Prevalence of human herpesvirus 8 DNA sequences in several patient populations. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2635–2638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2635-2638.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller G, Rigsby M O, Heston L, Grogan E, Sun R, Metroka C, Levy J A, Gao S J C-Y, Moore P. Antibodies to butyrate-inducible antigens of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in patients with HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1292–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neipel F, Albrecht J-C, Fleckenstein B. Cell-homologous genes in the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated rhadinovirus human herpesvirus 8: determinants of its pathogenicity? J Virol. 1997;71:4187–4192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4187-4192.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neipel F, Albrecht J C, Ensser A, Huang Y Q, Li J J, Friedman Kien A E, Fleckenstein B. Primary structure of the Kaposi’s sarcoma associated human herpesvirus 8. 1997. GenBank accession no. U93872. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neipel F, Ellinger K, Fleckenstein B. Gene for the major antigenic structural protein (p100) of human herpesvirus type 6. J Virol. 1992;66:3918–3924. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.6.3918-3924.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D E. Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rettig M B, Ma H J, Vescio R A, Pold M, Schiller G, Belson D, Savage A, Nishikubo C, Wu C, Fraser J, Said J W, Berenson J R. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of bone marrow dendritic cells from multiple myeloma patients. Science. 1997;276:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson G R, Schulz T F, Whitby D, Cook P M, Boshoff C, Rainbow L, Howard M R, Gao S J, Bohenzky R A, Simmonds P, Lee C, de Ruiter A, Hatzakis A, Tedder R S, Weller I V D, Weiss R A, Moore P S. Prevalence of Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus infection measured by antibodies to recombinant capsid protein and latent immunofluorescence antigen. Lancet. 1996;348:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals Hatem D, Babinet P, d’Agay M F, Clauvel J P, Raphael M, Degos L, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staskus K A, Zhong W, Gebhard K, Herndier B, Wang H, Renne R, Beneke J, Pudney J, Anderson D J, Ganem D, Haase A T. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J Virol. 1997;71:715–719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.715-719.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart J P, Janjua N J, Pepper S D, Bennion G, Mackett M, Allen T, Nash A A, Arrand J R. Identification and characterization of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 gp150: a virion membrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:3528–3535. doi: 10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00034574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stürzl M, Blasig C, Schreier A, Neipel F, Hohenadl C, Cornali E, Ascherl G, Esser S, Brockmeyer N H, Ekman M, Kaaya E E, Tschachler E, Biberfeld P. Expression of HHV-8 latency-associated T0.7 RNA in spindle cells and endothelial cells of AIDS-associated, classical and African Kaposi’s sarcoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:68–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<68::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virgin H W, IV, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck K E, Dal Canto A J, Speck S H. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol. 1997;71:5894–5904. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5894-5904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]