Abstract

Background

Tongue coating consists of oral bacteria, desquamated epithelium, blood cells, and food residues and is involved in periodontal disease, halitosis, and aspiration pneumonia. Recently, a tongue brush with sonic vibration was developed to clean the tongue. This comparative study examined the extent of tongue coating, its effects on the tongue, bacterial count particularly on the posterior dorsum of the tongue, and the degree of pain using a manual tongue brush and the newly developed sonic tongue brush.

Materials and methods

Patients’ extent of tongue coating and the quantity of bacteria were analysed before and after brushing with a sonic or manual nylon tongue brush. Moreover, the impressions of the dorsum linguae were obtained before and after brushing to establish models that were observed under a stereo microscope to evaluate tongue trauma. Pain caused during the use of these brushes was evaluated based on the numerical rating scale (NRS).

Results

The extent of tongue coating and number of bacteria decreased in both the sonic and manual nylon brush groups after tongue cleaning; however, no significant differences were noted. Tongue trauma evaluation revealed that the tongue surface was significantly scratched in the manual brush group compared with the sonic brush group. NRS-based pain evaluation revealed no significant differences.

Conclusions

The sonic brush was equally effective in removing tongue coating and bacteria compared with the manual brush. As the sonic brush does not cause tongue trauma, it may be considered a safe and effective cleaning tool of the tongue.

Key words: Bacterial testing, Tongue brush, Tongue cleaning, Tongue coating, Tongue injury

Introduction

Tongue coating is an agglomeration consisting of oral bacteria, desquamated epithelium, blood cells, and food residues.1 Various bacteria, including periodontal pathogens, exist on tongue coating and the dorsum linguae.2 Accordingly, the tongue is believed to act as a reservoir of periodontal pathogens.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Previous studies have demonstrated that tongue coating is a causative factor for halitosis and aspiration pneumonia in older people.7,8 Components of tongue coating that cause bad breath include volatile sulfur compounds (VSPs), short-chain fatty acids, and volatile nitrogen compounds.9, 10, 11 In particular, VSPs are primarily generated from tongue coating.12,13 Anaerobic bacteria, including periodontal pathogens, are responsible for generating VSPs from the tongue.13, 14, 15, 16 Moreover, various oral bacteria are involved in aspiration pneumonia in older people, and tongue coating is considered to be one of the sources of oral bacteria.17 Therefore, reducing the bacterial population in the oral cavity will greatly contribute to overall health as well as treatment of periodontal disease. In particular, it is important to remove tongue coating formed on the dorsum linguae.

Conventionally, various chemical and mechanical tongue-cleaning methods have been employed to remove tongue coating.18,19 Chemical methods include mouth rinsing/cleansing using products containing disinfectants and/or metallic ions.20 Mechanical methods involve the use of various utensils, such as tongue brushes, tongue scrapers, and gauze.21, 22, 23 However, as the tongue comprises delicate tissue, excessive use of tongue brushes and scrapers may damage the lingual mucosa and papillae. For this reason, it is essential to determine the quantity and frequency of applied force during brushing. Recently, a novel tongue-cleaning utensil utilising sonic vibration has been developed. Sonicare TongueCare+ tongue brush (Philips) is a spatula-shaped sonic tongue brush composed of thermoplastic elastomer (TPE) the working end of which is covered with minuscule protrusions. This part is attached to a sonic toothbrush. Studies have shown that this sonic tongue brush is effective in suppressing bad breath via functionality testing19 and hydrogen sulfide measurement.24 However, its effectiveness in removing tongue coating and its impact on the tongue and bacteria have not yet been evaluated.

This study used a manual tongue brush and the newly developed sonic tongue brush and comparatively evaluated the removal of tongue coating, damage to the tongue, pain during use, and bacterial count on the dorsum linguae.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

Of the patients without periodontal disease who had visited Tsurumi University Dental Hospital, 14 who consented to this study (7 men and women each; mean age 28 [range: 25–35] years) were enrolled. The study was conducted between June 2016 and December 2016. Sufficient explanation of the study was provided to patients and their written consent was obtained before staring the study. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study design. The patients were randomised into 2 groups of 7 patients each. The patients in each group were asked to use either a sonic or manual brush. The extent of tongue coating, bacterial count on the dorsum linguae, and damage to the tongue were measured before and after brushing. After a 2-week washout period, a crossover study was conducted, wherein the patients were asked to use the other brush. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tsurumi University Dental Hospital (approval No. 814), and was registered within a clinical trial database (UMIN-CTR No. UMIN000050802, http://www.umin.ac.jp). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design.

Instruments and usage

Sonicare TongueCare+ (Philips) was used as a sonic tongue brush in this study. TongueCare+ is a tongue brush attachment composed of TPE the working end of which is covered with 259 protrusions, each with a diameter of approximately 500 µm and height of 300–500 µm. A sonic toothbrush (Sonicare FLEXCare®, Philips) was used as a sonic wave generator. Each patient was asked to rinse their mouth with water once before tongue cleaning to wet their oral cavity and then clean the region extending from the lingual root to lingual apex by slowly moving the device back and forth (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2.

Tongue brushes used in this study. A, Toothbrush (Sonicare FLEXCare®, Philips) and ultrasonic tongue brush attachment (Sonicare TongueCare+, Philips). B, Manual tongue brush (Hi-Zac Tongue Brash, BEE BLAND MEDICO DENTAL, Osaka).

Hi-Zac Tongue Brash (BEE BLAND MEDICO DENTAL, Osaka) was used as a manual tongue brush in this study, in which 21 nylon hair bundles (each with a thickness of 3 mil and length of 5–5.5 mm) are aligned in 2 rows. Likewise, each patient was asked to clean the region extending from the lingual root to lingual apex by moving this brush back and forth for 2 minutes (Figure 2B).

Extent of tongue coating

Intraoral tongue images were captured before and after brushing at 2/3× magnification using a digital camera (Canon EOS Kiss X7). Images were captured whilst the patient was sticking out the tongue as forward as possible with their mouth open. Tongue coating was assessed based on Kojima's grading listed below25,26:

-

•

First-degree: one-third dorsum of the tongue and thin

-

•

Second-degree: two-thirds dorsum of the tongue and thin or one-third dorsum of the tongue and thick

-

•

Third-degree: two-thirds or more dorsum of the tongue and thin or two-thirds dorsum of the tongue and thick

-

•

Fourth-degree: two-thirds or more dorsum of the tongue and thick

Impact on the dorsum lingual mucosa

Prior to the experiment, trays for obtaining lingual impressions were prepared using an autopolymerising acrylic resin (OSTRON II, GC Japan). The impressions of the patient's dorsum linguae were obtained using a silicone impression material (EXAMIXFINE <injection type>, GC Japan) before and after brushing. After obtaining an impression, dental stone (NEW FUJI LOCK, GC Japan) was used to establish tongue models, which were then observed at 50× magnification under a stereo microscope (SZX7, Olympus).

Lingual bacterial count

A bacteria counting device (Bacteria Counter, Panasonic Healthcare) was used to enumerate bacteria. A constant-pressure sampling instrument fitted with a sterile swab was used to collect samples under constant pressure conditions. With the sterile swab positioned horizontally to the dorsum linguae, the middle of the dorsum linguae was scraped back and forth thrice under a constant pressure of 20 ± 5 grams. Each collected sample was placed in a test tube containing 5 mL of purified water and stirred, after which 1 mL of the sample solution was transferred to a disposable cup via a pipette. Subsequently, measurement was recorded using the counting device. The measured value was then multiplied by the dilution factor to obtain the bacterial count. Measurements obtained using this device have been reported to be highly correlated with the actual bacterial count in the culture.27

Evaluation of usability

The degree of pain experienced whilst using the sonic or manual brush was evaluated based on the NRS. After using the brush, the patient was asked to assess the degree of pain experienced.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

Because the cause of halitosis is thought to be derived from tongue coating, the sample size was calculated with reference to the article reported by Casemiro et al,22 in which a tongue brush was used. The sample size for this crossover study was calculated using SPSS® Statistics software (ver. 19.0, IBM) with a statistical power of 80% and a significance level of .05 using the mean difference (2.8) and standard deviation (0.4) of the halitosis score from the Casemiro et al study. As a result, it was determined that the sample size should be at least 10 patients. Our study enrolled 14 patients, taking into account the possibility of dropout during the study period.

After the eligibility of the selected participants was determined, they were randomly divided into the sonic and tongue brush groups. Each brush allocation was performed by an allocation overseer (KA) who was not directly involved in the study. After fixating the data for analysis, the test data were used in the analysis. Intragroup comparison of the extent of tongue coating, tongue trauma, pain evaluation, and lingual bacterial count was conducted using Mann–Whitney U test, whereas intergroup comparison was performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® Statistics software.

Results

All the participants (N = 14) completed the study and used the 2 brushes; no dropouts occurred during the study. Participants did not experience any adverse events, such as tongue damage.

Extent of tongue coating

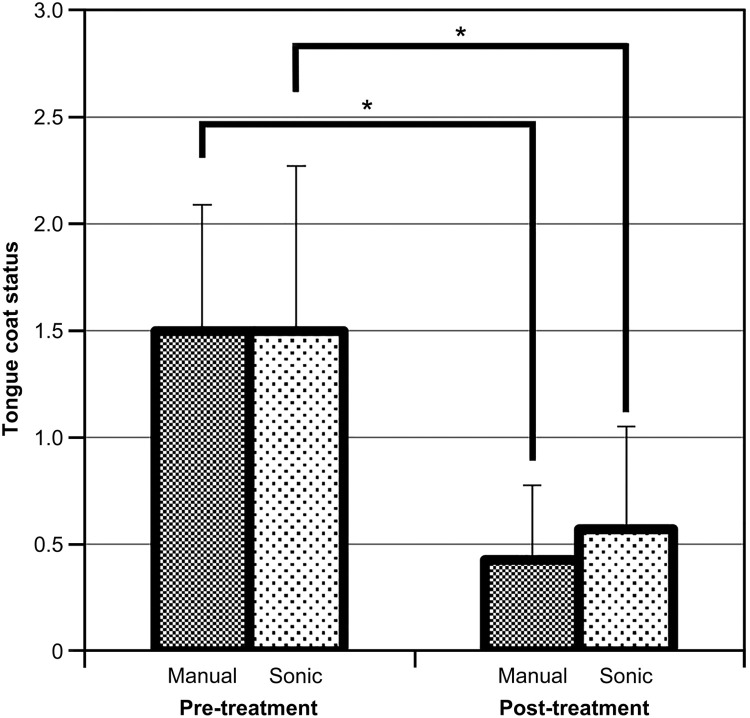

Based on the lingual images before and after brushing, the extent of tongue coating was evaluated based on Kojima's grading. The results revealed that the extent of tongue coating after brushing significantly decreased from that before brushing in both sonic and manual brush groups (P > .01) (Figure 3). However, no significant differences were observed between the 2 groups.

Fig. 3.

The extent of tongue coating before and after manual or sonic brushing was evaluated based on Kojima's grading. Tongue coating significantly decreased in both sonic and manual brush groups (P > .01). However, no significant differences were noted between the 2 groups.

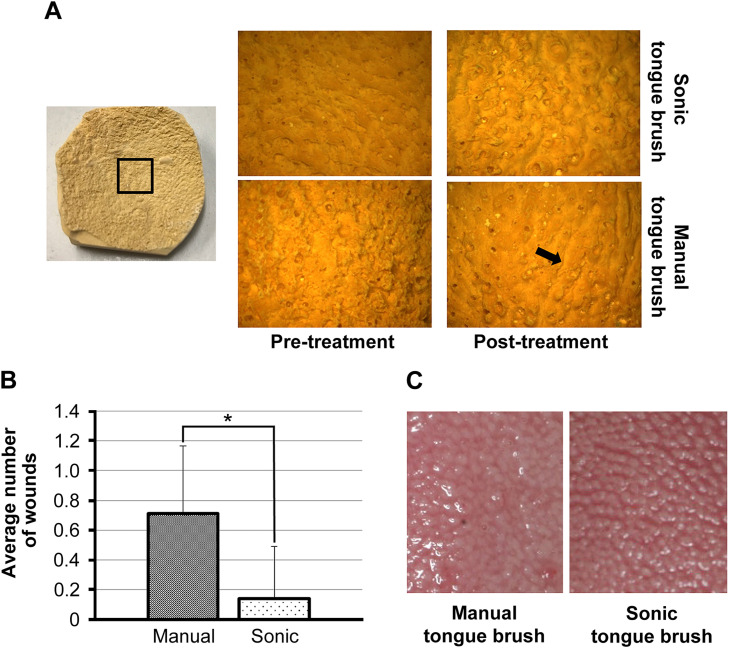

Impact on the dorsum lingual mucosa

The stereomicroscopic observation of the dorsum lingual mucosa models after tongue cleaning revealed multiple injuries (scratches) on the tongue surface, which may have been caused by the tongue brush in the manual brush group. In contrast, such injuries were scarcely observed in the sonic brush group (Figure 4A). The numbers of these scratches were determined and comparatively analysed. The results showed that the number of scratches on the tongue surface was statistically significantly lower in the sonic brush group than in the tongue brush group (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Dorsum linguae models were established and evaluated before and after brushing under a stereo microscope at 50× magnification. A, Damage to the tongue surface. Multiple longitudinal lines (arrows) were noted on the tongue surface after brushing in the manual brush group. In addition, lingual papillae were morphologically unclear after brushing. However, almost no damage was noted on the tongue surface after brushing in the sonic brush group, with the maintenance of lingual papillae. B, The number of injuries on the dorsum linguae after manual or sonic brushing. This number was significantly lower in the sonic brush group than in the manual brush group (P > 0.05). C, Changes in the tongue surface. Lingual papillae on the tongue surface were morphologically unclear in the manual brush group. Almost no damage was noted on the tongue surface in the sonic brush group, with the maintenance of lingual papillae.

As there were fewer scratches on the tongue surface in the sonic brush group, the condition of the dorsum lingual mucosa was assessed based on the lingual digital camera images. Although the tips of lingual papillae appeared to have been scraped off after manual brushing, lingual papillae remained healthy after sonic brushing (Figure 4C).

Bacterial count

The bacterial count was evaluated after brushing via the bacteria counting device. The results showed that the bacterial count significantly decreased from 3.02 × 107 to 1.65 × 107 CFU/mL in the sonic brush group (P > 0.01). Likewise, the bacterial count significantly decreased from 2.99 × 107 to 9.61 × 106 CFU/mL in the manual brush group (P > 0.01) (Figure 5A). However, no significant differences in bacterial count were noted between the 2 groups.

Fig. 5.

A, Bacterial count after brushing. The bacterial count after brushing significantly decreased compared with that before brushing in both groups. However, no significant intergroup differences in bacterial count were noted. B, The degree of pain during brushing was evaluated based on the numerical rating scale. No significant differences were noted after brushing between the sonic and manual brush groups.

Evaluation of usability

The usability of each brush was evaluated based on the NRS. The mean NRS score was 1.78 for the manual brush and 1.07 for the sonic brush. Neither brush scored high points. No statistically significant differences were noted in usability between the sonic and manual brush groups (Figure 5B).

Discussion

Cleaning the oral cavity, including the tongue, is becoming increasingly important in managing periodontal disease and meet societal demands to prevent bad breath. Moreover, it is essential to maintain general health and prevent diseases, including aspiration pneumonia, in the current aging society. However, the tongue is a delicate soft tissue responsible for taste and other sensations. Accordingly, it is important to remove tongue coating and bacteria without damaging the tongue itself. This study revealed a significant decrease in the extent of tongue coating after brushing in both manual and sonic brush groups. Although the manual brush group removed slightly more tongue coating than the sonic brush group, no statistically significant differences were noted. Thus, both brushes were considered to be comparably effective. In contrast, regarding the impact of either brush on the dorsum lingual mucosa, several scratches apparently caused by brushing were noted on the surface of the dorsum linguae in the manual brush group. This finding indicated that the manual brush can damage the tongue if attention is not paid to the applied force and frequency of brushing. Moreover, the presence of scraped-off lingual papillae on the tongue surface after using the manual brush raised concern that frequent brushing with a strong force may damage the lingual mucosa and cause disorders such as dysgeusia. Yaegaki et al18 reported that brushing with a wire-flocked tongue brush at a pressure of 100 g or less might have avoided damage to the dorsum of the tongue. The tongue brush used in the current study had nylon bristles directly planted on the head, and it is possible that the dorsum of the tongue was damaged because of the excessive force applied. In contrast, the sonic tongue brush may be capable of safely cleaning the tongue as it neither damages the dorsum linguae nor affects lingual papillae. The tongue of an elderly person is often smoothened due to adverse drug reactions, leaving it susceptible to damage. Thus, it is crucial to develop less damaging tongue-cleaning techniques.

Intragroup comparison before and after brushing revealed that the bacterial count significantly decreased in both sonic and manual brush groups. However, no significant differences in bacterial count were noted between the 2 groups. Kikutani et al27 demonstrated that the tongue coating score was correlated with the bacterial count, consistent with our study finding. In the study reported by Li et al,24 the group that combined the sonic tongue brush with an antibacterial tongue spray exhibited a reduced number of bacteria compared with the mouthwash or manual tooth brush group. In the present study, there was no significant difference because no antibacterial spray was used. A tongue brush with nylon bristles can remove tongue coating and decrease the bacterial count by mechanically scraping the tongue surface, whereas a sonic tongue brush possibly performs the same function through gentle tapping via sonic vibration. Presumably, this mechanism enables the sonic tongue brush to eliminate bacteria that are present deep within lingual papillae. To fully use the sonic tongue brush, it is a prerequisite to maintain moisture within the oral cavity, facilitating an environment where sonic vibration can be easily transmitted. Furthermore, to ensure that the detached tongue coating and bacteria do not reattach to the tongue, it is critical to thoroughly rinse the mouth with mouthwash after sonic brushing. There are limitations in this study. The sample size was small, so it is possible that no difference was detected. Increasing the sample size of tongue coating and bacterial count data is necessary for future research.

The present study had several limitations. Mainly, the sample size was small, which may explain the absence of differences between the groups. Increasing the sample size will be necessary in future research.

Postuse evaluation based on the degree of pain did not reveal any significant intergroup differences, with low pain scores in both groups. Although microvibration generated by the sonic tongue brush was unlikely to be perceived as painful, its score was similar to that of the manual brush. The patients might have assessed discomfort due to sonic vibration as pain. As sonic vibration is an unprecedented sensation, users may require some time to get accustomed to it.

Conclusions

The sonic tongue brush was equally effective in removing tongue coating and bacteria on the tongue surface as the manual tongue brush. Moreover, it was considered a safer tongue-cleaning technique, considering its ability to remove tongue coating and bacteria via sonic vibration whilst avoiding damage to the tongue, unlike the manual tongue brush that scrapes off lingual papillae.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Takuya Yokoyama and Dr Ayaka Suzuki for their assistance in the clinical examination and microbiological sampling of the patients who participated in this study. The authors had full control of the data and analyses and received no commercial input in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Satoshi Shirakawa conceived and designed the analysis, performed the analysis, and drafted the paper. Takatoshi Nagano conceived and designed the analysis and contributed to data/analysis tools. Yuji Matsushima acquired the data and revised the manuscript. Akihiro Yashima Matsushima acquired the data and revised the manuscript. Kazuhiro Gomi conceived and designed the analysis and drafted the paper.

Funding

No external funding, apart from the support of the authors’ institution, was available for this study.

Conflict of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.identj.2023.10.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Quirynen M, Mongardini C, van Steenberghe D. The effect of a 1-stage full-mouth disinfection on oral malodor and microbial colonization of the tongue in periodontitis. A pilot study. J Periodontol. 1998;69:374–382. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka M, Yamamoto Y, Kuboniwa M, et al. Contribution of periodontal pathogens on tongue dorsa analyzed with real-time PCR to oral malodor. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe S, Ishihara K, Adachi M, Okuda K. Tongue-coating as risk indicator for aspiration pneumonia in edentate elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortelli JR, Aquino DR, Cortelli SC, et al. Etiological analysis of initial colonization of periodontal pathogens in oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1322–1329. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02051-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdeo A, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Biofilms in the edentulous oral cavity. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishi M, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Takahashi M, et al. Prediction of periodontopathic bacteria in dental plaque of periodontal healthy subjects by measurement of volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishi M, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Takahashi M, Kishi K, Kimura S, Yonemitsu M. Relationship between oral status and prevalence of periodontopathic bacteria on the tongues of elderly individuals. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:1354–1359. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoneyama T, Yoshida M, Matsui T, Sasaki H. Oral care and pneumonia. Oral care working group. Lancet. 1999;354:515. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)75550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonzetich J. Production and origin of oral malodor: a review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. J Periodontol. 1977;48:13–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonzetich J. Bad breath: research perspectives. Edited by M. Rosenberg. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing-Tel Aviv University; 1995, p. 15.

- 11.Kopstein J, Wrong OM. The origin and fate of salivary urea and ammonia in man. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;52:9–17. doi: 10.1042/cs0520009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air from clinically healthy subjects and patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol Res. 1992;27:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1992.tb01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Broek AM, Feenstra L, de Baat C. A review of the current literature on management of halitosis. Oral Dis. 2008;14:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosy A, Kulkarni GV, Rosenberg M, McCulloch CAG. Relationship of oral malodor to periodontitis: evidence of independence in discrete subpopulations. J Periodontol. 1994;65:37–46. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Boever EH, Loesche WJ. Assessing the contribution of anaerobic microflora of the tongue to oral malodor. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1384–1393. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Boever EH, De Uzeda M, Loesche WJ. Relationship between volatile sulfur compounds, BANA-hydrolyzing bacteria and gingival health in patients with and without complaints of oral malodor. J CIin Dent. 1994;4:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kikuchi R, Watabe N, Konno T, Mishina N, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:251–253. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaegaki K, Coil JM, Kamemizu T, Miyazaki H. Tongue brushing and mouth rinsing as basic treatment measures for halitosis. Int Dent J. 2002;52:192–196. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saad S, Gomez-Pereira P, Hewett K, Horstman P, Patel J, Greenman J. Daily reduction of oral malodor with the use of a sonic tongue brush combined with an antibacterial tongue spray in a randomized cross-over clinical investigation. J Breath Res. 2016;10 doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/1/016013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roldán S, Winkel EG, Herrera D, Sanz M, Van Winkel hoff AJ. The effects of a new mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine,cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate on the microfiora of oral halitosis patients: a dual-centre, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:427–434. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.20004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedrazzi V, Sato S, de Mattos Mda G, Lara EH, Panzeri H. Tongue-cleaning methods: a comparative clinical trial employing a toothbrush and a tongue scraper. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1009–1012. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.7.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casemiro LA, Martins CH, de Carvalho TC, Panzeri H, Lavrador MA. Pires-de-Souza Fde C. Effectiveness of a new toothbrush design versus a conventional tongue scraper in improving breath odor and reducing tongue microbiota. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:271–274. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000400008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Outhouse TL, Fedprpwicz Z, Keenan JV, Ai-Alawi R. A Cochrane systematic review finds tongue scrapers have short-term efficacy in controlling halitosis. Gen Dent. 2006;54:352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Lee S, Stephens J, et al. A randomized parallel study to assess the effect of three tongue cleaning modalities on oral malodor. J Clin Dent. 2019;30(Spec No A):A30–A38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojima K. Clinical studies on the coated tongue. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;31:1659–1678. doi: 10.5794/JJOMS.31.1659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashida S, Funahara M, Sekino M, et al. The effect of tooth brushing, irrigation, and topical tetracycline administration on the reduction of oral bacteria in mechanically ventilated patients: a preliminary study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:67. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikutani T, Tamura F, Takahashi Y, Konishi K, Hamada R. A novel rapid oral bacteria detection apparatus for effective oral care to prevent pneumonia. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e560–e565. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.