Abstract

Aims:

To characterize Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients' experiences of patient engagement in AYA oncology and derive best practices that are co-developed by BIPOC AYAs and oncology professionals.

Materials & methods:

Following a previous call to action from AYA oncology professionals, a panel of experts composed exclusively of BIPOC AYA cancer patients (n = 32) participated in an electronic Delphi study.

Results:

Emergent themes described BIPOC AYA cancer patients' direct experiences and consensus opinion on recommendations to advance antiracist patient engagement from BIPOC AYA cancer patients and oncology professionals.

Conclusion:

The findings reveal high-priority practices across all phases of research and are instructional for advancing health equity.

Keywords: AYA, BIPOC, patient engagement, real-world evidence, survivorship, young adult

In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide racial justice movement's mass mobilization against systemic racism have prompted US oncology researchers and advocates to heighten focus on greater inclusion of minoritized patients who have been underrepresented in cancer research. In 2022, an estimated 87,050 of the 1.9 million new cancer cases in the USA were diagnosed among adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients aged 15–39 years [1]. AYAs face heightened vulnerabilities compared with pediatric and older adult oncology populations, including disparities in diagnosis [2], survival rates [3], financial hardship [4] and access to cancer treatments [5], with implications for long-term survivorship [6]. Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC; also referred to as ‘racially minoritized’) AYA cancer patients experience further marginalization. For example, Black AYAs in the USA experience 13% lower 5-year relative cancer survival compared with their Non-Hispanic White peers [7].

Disparities & health equity

Evidence shows that the lived experiences many minoritized BIPOC AYA cancer patients in the USA encounter are themselves expanded adverse childhood experiences, thereby amplifying the impact on their overall well-being [8,9]. Expanded adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are defined as potentially traumatic events that occur outside the home during one's childhood and are linked to negative long-term health consequences [10]. Developmental psychologists suggest that racially minoritized AYAs by definition have restricted access to power and resources, which challenges their psychological experiences and perspectives in ways not present among AYAs in the dominant racial group [11]. Due to their marginalized positionalities, BIPOC AYAs experience intensified structural racism in medical settings, which includes, notably, the research studies that seek to engage with patients and their respective communities [12].

Empirical evidence underscores heightened disparities among BIPOC AYA cancer patients with greater risk of marginalization in recruitment into clinical trials [13], racially biased communications from cancer care providers [14] and inferior overall survival outcomes compared with Non-Hispanic White counterparts [1,15]. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the widespread prevalence of COVID-19 has magnified significant disparities in its impact on racially minoritized populations, exacerbating pre-existing social issues related to anti-Black racism and police brutality [16] as well as anti-Asian racism and violence [17].

As the COVID-19 crisis unfolded, starkly unequal effects of factors such as gun violence, poverty and healthcare accessibility exposed an undeniable connection between racism and health equity. During and since this time, predominantly White-led organizations, who were eager to display their allyship, increased demands on BIPOC AYA cancer patients to engage in their recently expanded advocacy initiatives (e.g., inclusive marketing to improve business outreach) despite the disproportionate impact of intersecting health and social crises on these young patients. These advocacy endeavors raised questions about the fundamental motivations of the organizations involved and the extent to which they authentically served the interests of BIPOC AYAs [18].

Antiracism & healthcare research

Despite the resurgence of mainstream interest in racial inequities, incidents of racialized violence, defined by the COVID-19 Task Force on Racism and Equity as injustices that sit at the intersection of racism and violence [19], have persisted. Likewise, evidence of unequal treatment resulting from systemic racial bias in the healthcare workforce has continued to build [20]. Healthcare researchers responded with calls for action promoting antiracism [21] and the restructuring of healthcare systems [22,23] to promote health equity toward a shared vision of liberation from disparities and justice. More specifically, cancer researchers demanded attention to the impacts of structural racism on cancer disparities that were amplified by the co-occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., lack of access to cancer care due to fractured social support networks; lack of transportation to medical appointments; and compounding practical needs such as food security, housing stability and continuous access to utilities) [24]. Now more than ever, it is increasingly challenging for BIPOC AYA patients to engage in research and advocacy efforts, and organizational leaders must respond with meaningful and trustworthy practices that safeguard the well-being of minoritized AYAs who cope with the profound challenges of life-threatening illness against the backdrop of racism.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of the current study was to co-create best practices to promote antiracist research across four stages of the empirical research process via the joint expertise of BIPOC AYAs in the present study and AYA oncology professionals in a previous call to action [21]. More specifically, the current study aimed to characterize BIPOC AYA cancer patients' experiences with conventional and recommended antiracist approaches to patient engagement in AYA oncology research and advocacy. The findings provided insights on successful and unsuccessful engagement, which may inform the development of effective antiracist patient engagement practices that promote the health and well-being of BIPOC AYA cancer patients.

Conceptual framework

Our study was guided by the antiracist research framework of Goings et al. [25], which includes ten foundational principles (e.g., antiracist research centers BIPOC experiences; antiracist researchers prioritize community engagement of the target population; and antiracist research uses team science to benefit from diverse perspectives) and numerous recommendations for antiracist researchers [25]. Antiracist research stems from antiracism and assumes that racism is maintained within institutions, seeks to dismantle racism using nonracist research methods and requires that study findings are disseminated to benefit and empower the target population. It follows that antiracist research is research that reduces racial inequality by expressing and/or supporting the idea that racial groups are equal [26].

Rather than individual actors alone, the networks of all individuals work in concert to reinforce racism. We therefore use the term ‘systemic racism' according to Bonilla-Silva's [27] interpretation that systemic racism is a structural part of society and that “if racism is systemic, we all take part in it“ [27]. Antiracist researchers strive to transform systems to ensure equity. This overarching goal informed the current study, which sought to identify potential structural and research changes that may correct long-standing legacies of systemic racism that exacerbate and contribute to persistent health inequities.

Materials & methods

Previous call to action

Previously, a subset of our multidisciplinary team of AYA oncology professionals (CK Cheung, RD Tucker-Seeley, SJ Davies, ML Gilman, KA Miller, G Lopes and MA Lewis) published recommendations for antiracist patient engagement in AYA oncology research and advocacy [21]. In the current study, a panel of BIPOC AYA cancer patients shared their experiences and perspectives on antiracist patient engagement and reactions to the recommendations made in the previous call to action from AYA oncology professionals. The highest priority recommendations for antiracist patient engagement from AYA oncology professionals in the previous call to action were presented in the form of survey questions posed to BIPOC AYA participants in the current study. Data from these sources were combined to co-create best practices for antiracist patient engagement drawing from their joint expertise.

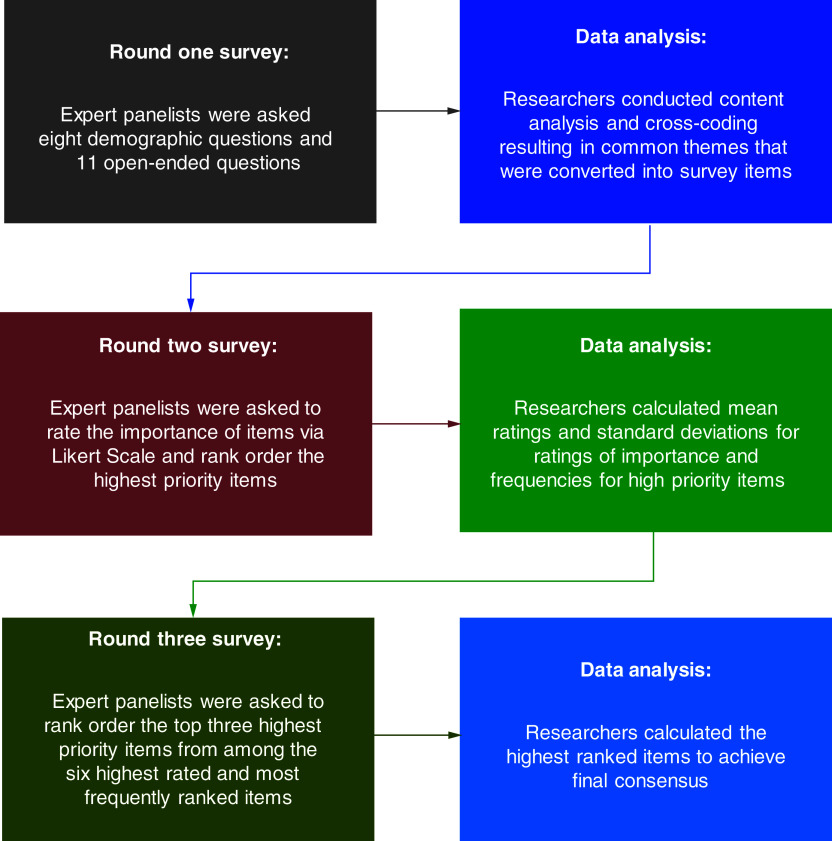

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute framework for patient engagement and core principles [28] served as the organizational structure for discussing high-priority issues across all research activities in the previous call to action and the current study. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute's four stages of research encompass 1) ‘topic selection and research prioritization', which refers to identifying and planning the purpose of the study; 2) ‘proposal review: design and conduct of research', which refers to planning and executing the study; 3) ‘dissemination and implementation of results', which refers to publishing and sharing the knowledge produced in the study and 4) ‘evaluation', which refers to assessment of the effectiveness of dissemination and implementation strategies. Recommendations from the seven AYA oncology professionals in the previous call to action [21] were developed by a similar consensus method as the current study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. . Recommendations for antiracist patient engagement in research from adolescent and young adult oncology professionals.

1Recommendations are organized according to PCORI framework for patient engagement's four stages of research.

AYA: Adolescent and young adult; BIPOC: Black, Indigenous and People of Color.

Reproduced from the previous call to action [21].

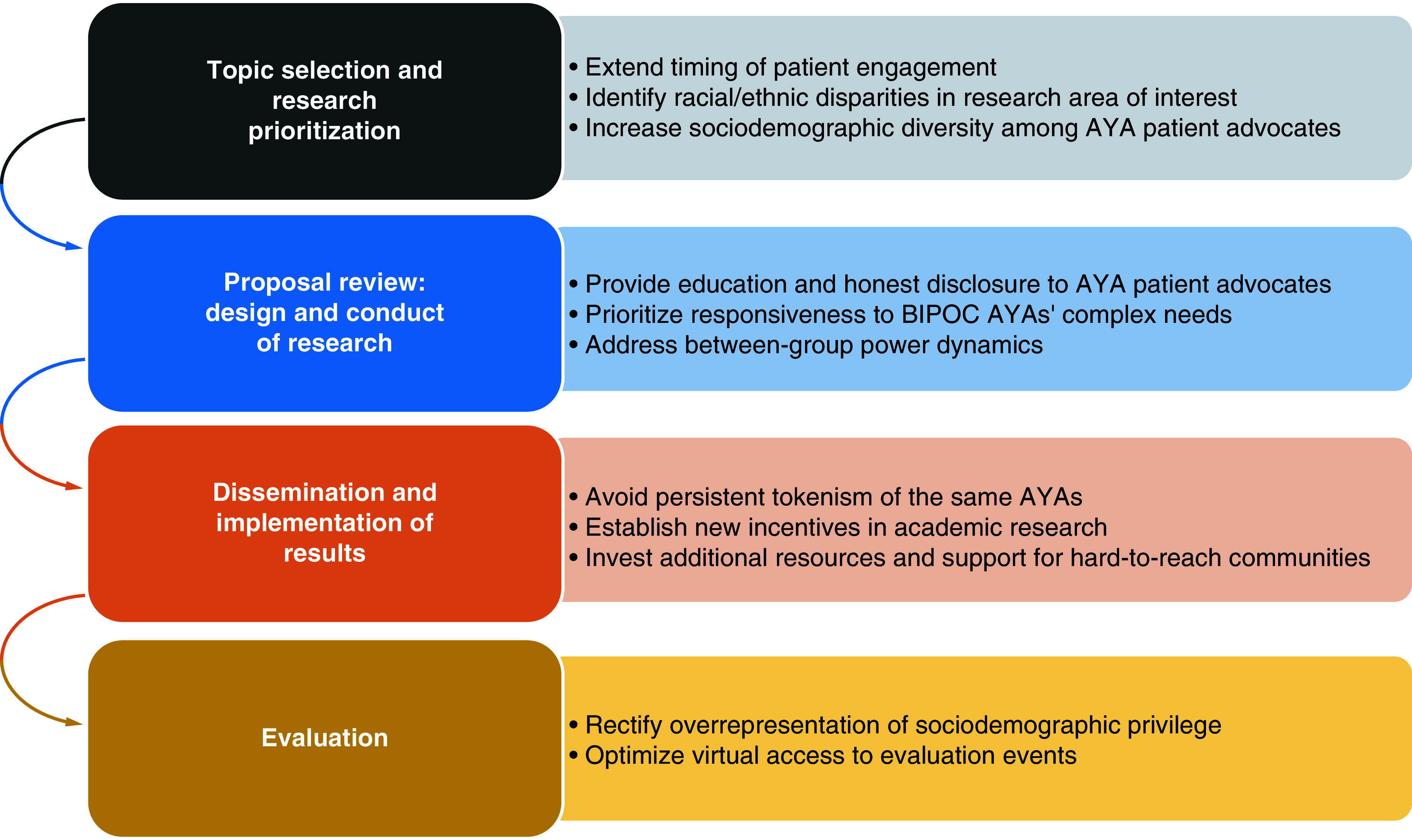

The Delphi method

The Delphi method is a mixed methods research technique used to achieve consensus agreement on a specific topic by soliciting the anonymous opinions of subject matter experts via iterative survey rounds (Figure 2) [29,30]. The current research was an electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) study conducted via online surveys and digital platforms that responded to AYAs' accessibility preferences [31]. The investigators surveyed a panel of experts defined as self-identified BIPOC patients diagnosed with cancer between ages 15 and 39 years. Researchers used a modified e-Delphi [32] technique that consisted of three (as opposed to four) electronic survey rounds that were designed and optimized for respondents to easily and conveniently complete on their mobile devices. Consistent with extant Delphi studies of AYA cancer patients, the classic Delphi method composed of four survey rounds [33] was modified to three survey rounds to reduce respondent burden [34]. Each survey round had to be completed by all participants before the next survey round could begin, as survey items in one round were derived from results from the preceding survey round.

Figure 2. . Modified Delphi technique utilized in the current study.

The electronic Delphi study was a Delphi technique modified by administering three survey rounds via online surveys and audio-recorded Zoom interviews. Round One generated relevant survey items for expert participants' ratings of importance and preliminary rankings of priority in Round Two, which ultimately informed the ranking of short-listed items in Round Three to achieve a final consensus.

Advantages of the Delphi method

The Delphi's anonymous approach is particularly advantageous for arriving at agreement among leading experts in smaller communities or highly specialized settings who may be familiar with one another, as it mitigates the influence of dominant voices and reduces fear of repercussions or judgment [35]. Its mixed methods design combines qualitative content analyses of open-ended responses in the first survey round with quantitative ratings and rankings of the importance of these responses in subsequent survey rounds to arrive at consensus opinions [29,30]. In AYA oncology, Delphi studies have generated consensus opinions of healthcare providers to set priorities for developing interventions that respond to unmet needs and barriers to participation in survivorship care [36–38].

Sample & participant recruitment

In this study, e-Delphi experts were self-identified BIPOC patients who were diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 15 and 39 years (inclusive of individuals on treatment and in post-treatment survivorship) and willing to share their experiences and perspectives on patient engagement in cancer research (n = 32; Table 1). This purposive sample of participants was recruited solely through digital means via digital flyers containing the Round One survey quick response code and URL, which were disseminated widely across the networks of our multidisciplinary and diverse investigator team via email, Instagram and Twitter. Potential participants responded to flyers with their personal email address and were then directed to a URL to complete eligibility screening and the Round One survey.

Table 1. . Participant characteristics.

| Variable | Participants (n = 32) | Nonparticipants† (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 22 (69) | 9 (100) |

| Male | 10 (31) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 6 (19) | 2 (22) |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latinx | 26 (81) | 7 (78) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Black or African–American | 20 (63) | 6 (67) |

| Asian | 5 (16) | 1 (11) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (9) | 1 (11) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| More than one race, n (%) | ||

| Black or African–American and American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African–American, Asian and American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 1 (11) |

| Asian and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 2 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Age at diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Teens | 3 (9) | 1 (11) |

| 20s | 14 (44) | 4 (44) |

| 30s | 15 (47) | 4 (44) |

| Cancer diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Breast | 10 (31) | 2 (22) |

| Stomach | 3 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 2 (6) | 1 (11) |

| Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 3 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Cervical | 2 (6) | 2 (22) |

| Leukemia | 4 (13) | 1 (11) |

| Multiple cancer types | 3 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Other carcinomas/types‡ | 5 (16) | 3 (33) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 5 (16) | 1 (11) |

| Some college | 2 (6) | 3 (33) |

| College degree | 15 (47) | 4 (44) |

| Graduate degree | 10 (31) | 1 (11) |

| Household income, n (%) | ||

| Less than US$24,999 | 2 (6) | 1 (11) |

| US$25,000–49,999 | 7 (22) | 2 (22) |

| US$50,000–74,999 | 9 (28) | 3 (33) |

| US$75,000 and greater | 12 (38) | 1 (11) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6) | 2 (22) |

41 Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult patients were initially recruited as expert participants; nine were lost to attrition between survey rounds and excluded from the final electronic Delphi panel of Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult patient experts (n = 32).

Lost to attrition between survey rounds.

Includes liver, oral and meningioma brain tumor.

We initially recruited an e-Delphi panel of 41 BIPOC AYA experts who responded to the Round One survey. Table 1 displays participant characteristics, including nine individuals lost to attrition between survey rounds, a common challenge in e-Delphi surveys [39]. Of the nine participants lost, all were of Black race and female sex, although one of these individuals identified as being mixed race (Black or African–American, Asian and Native American). The final study sample comprised 32 BIPOC AYA participants who were diagnosed between ages 15 and 39 years and were 21–49 years old at the time of the study.

The study protocol was approved by the University of Maryland Baltimore Institutional Review Board (HP-00095303), and the investigators adhered to the institution's policies for the protection of human subjects. In appreciation of their time and effort, study participants were provided a $50 eGift card upon successfully completing the Round Three final survey.

Round One: open-ended questions

Procedure

Investigators utilized the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute's four stages of research activities and six core principles for patient engagement [28] as an organizational structure to construct the Round One survey. Box 1 presents representative survey responses from BIPOC AYA cancer patients who reported experiences of patient engagement across the research continuum.

Box 1. Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult cancer patients' marginalized experiences across the research continuum.

Investigators utilized the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute's four stages of research and six core principles to organize survey questions that generated representative responses from the expert panel of Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult cancer patients.

In Round One of the online Qualtrics survey, e-Delphi panelists answered eight demographic questions and 11 open-ended questions about AYA cancer research focusing on patient engagement, which required approximately 35–45 min to complete. Among these questions, eight were central questions asking panelists to describe successful and unsuccessful engagement of BIPOC AYAs and respond to the recommendations from AYA oncology professionals in the preceding call to action. Survey questions were collaboratively developed by members of our research team who also identified as BIPOC AYA cancer patients and oncology professionals.

Because of participant drop-off during text responses, we offered the option of audio-recorded Zoom interviews, with 41% (n = 17) choosing this method. Interviewers were members of the research team within the AYA age range (15–39 years old; T Katerere-Virima, LE Helbling and CD Simmons) who also transcribed audio recordings of participant interviews using Otter.ai software. The Round One survey took 4 months (April to August 2021) to complete data collection.

Data analysis

Upon receiving Round One survey responses, two team members (BN Thomas and RE Brandon) initially organized them into clusters based on positive and negative patient engagement experiences while minimizing redundancy. These researchers then cross-coded and sorted ideas within these clusters. Following this, three additional team members (VA Ross, H Lee and CK Cheung) conducted qualitative content analysis using an inductive process. They identified common patterns, developed textual descriptions, categorized them into themes and converted them into survey items. Thematic saturation was reached when no new themes emerged. Cross-coding of each interview by three researchers included discussions to ensure inter-rater reliability. This content analysis was completed in 3 months (August to October 2021), resulting in nine to 15 multiple choice response options for each question in the Round Two survey.

Round Two: ratings & rankings

Procedure

The Round Two survey retained the eight central questions from Round One. Here panelists were tasked with rating the importance of response options and ranking their top three priorities (Table 2). About half of participants needed three to five email reminders to complete the survey, and data collection for Round Two was completed in 2 months (September to October 2021). All 35 participants opted for independent online survey completion. There were no open-ended questions in the second survey.

Table 2. . Items rated of highest importance in patient engagement by Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult cancer patient experts.

| Item | Mean (Times ranked top three priority)† |

|---|---|

| Question 1: Characteristics of cancer research or advocacy that successfully includes perspectives of racially minoritized teen or young adult patients | |

| 1. Build relationships with communities and listen to patients who are not usually heard | 6.76 (23) |

| 2. Ensure that BIPOC individuals are not taken advantage of or tokenized | 6.76 (10) |

| 3. Recruit a diverse range of BIPOC patients and let them give actual input into the study | 6.69 (20) |

| 4. Utilize a diversity of participants in all sociodemographic aspects, not just race (e.g., education, class, age at diagnosis) | 6.59 (18) |

| 5. Address practical barriers to participation, such as hiring interpreters for non-English-speaking patients | 6.48 (8) |

| 6. Employ trustworthy BIPOC leaders to head research projects | 6.45 (17) |

| Question 2: Topic selection and research prioritization | |

| 1. Increase diversity among those patients who also serve as advocates | 6.55 (15) |

| 2. Identify racial/ethnic inequities in the research topic of interest | 6.48 (19) |

| 3. Employ more BIPOC researchers conducting studies to make participants comfortable | 6.48 (16) |

| 4. Engage patients earlier in the process and at higher levels within institutions | 6.38 (19) |

| 5. Include more intersectional populations, such as BIPOC patients who identify as LGBTQ+ | 6.34 (12) |

| 6. When explaining the purpose of the study/project, also communicate the impact the issue can have on BIPOC patients in particular | 6.24 (15) |

| Question 3: Proposal review: design and conduct of research | |

| 1. Provide education and be honest about what participating in cancer research and advocacy really entails | 6.72 (12) |

| 2. Promote the significance of participating in cancer research and acknowledge how AYA patient advocates are important and really matter in research projects | 6.69 (13) |

| 3. Be honest and authentic and break things down for patients into explanations they can easily understand | 6.66 (14) |

| 4. Utilize more BIPOC researchers actually doing the research to organically make people feel engaged. Diversity cannot be forced | 6.62 (17) |

| 5. Give BIPOC AYA patients information and access to participation in research studies regardless of their financial situation, social standing, etc. | 6.59 (17) |

| 6. Identify barriers to recruitment and participation among BIPOC AYA patients and reduce these barriers (e.g., by improving outreach, increasing methods of interaction/communication and/or helping participants feel safer and more secure in the research setting/process) | 6.45 (23) |

| Question 4: Dissemination and implementation of results | |

| 1. Use community peers and peer-based language and methods to present results from credible sources instead of incomprehensible jargon that may potentially discourage patients | 6.66 (11) |

| 2. Invest in outreach to BIPOC AYA cancer patients who are commonly overlooked or ignored and who do not have easy access to opportunities to participate (e.g., patients in rural settings) | 6.62 (14) |

| 3. Provide results for different levels of comprehension to reduce barriers to access so patients who have a higher level of understanding can access more complicated information without compromising the accessibility of patients who may be younger or otherwise need more simplified explanations | 6.55 (23) |

| 4. Get research results out to the groups/communities that can really use them, not just other researchers | 6.52 (15) |

| 5. Keep it brief and creative and use social media and technology to disseminate results in a way that is easy for patients to understand and use | 6.41 (17) |

| 6. Invite a diversity of new BIPOC AYA patient advocates to participate in research and stop using the same patient advocates repeatedly | 6.10 (16) |

| Question 5: Evaluation of dissemination and implementation strategies | |

| 1. Provide virtual access to conferences, committee meetings, etc., so participation is easier for AYAs | 6.66 (13) |

| 2. Allow patient advocates to provide truly anonymous feedback so they can be completely honest without concern of repercussions like not being invited to participate again | 6.55 (21) |

| 3. Promote and improve virtual access to conferences and meetings to reduce barriers to attendance | 6.48 (14) |

| 4. Compensate BIPOC AYA patients for their time, energy and expertise | 6.48 (18) |

| 5. Be flexible with scheduling patients' participation whenever possible | 6.48 (10) |

| 6. Enable BIPOC AYA patients to actually participate in the conference or meeting and understand and address what they need to get there; otherwise, these events are useless | 6.38 (20) |

| Question 6: Transparency–honesty–trust | |

| 1. Transparency, honesty and trust are the foundation of everything, and researchers cannot do anything without them | 6.72 (19) |

| 2. Implementing open and honest communication will lead to more trust | 6.59 (12) |

| 3. It is important to build trust from the beginning and be transparent in order to avoid doing harm and to ensure that participants feel safe | 6.59 (21) |

| 4. Trustworthy relationships are especially important for AYAs, who are just coming into their own and need to feel like there is trust between them and those they interact with | 6.55 (19) |

| 5. If there is trust, BIPOC patients will be more likely to share information that is going to be useful without holding anything back | 6.52 (15) |

| 6. BIPOC patients already have mistrust of the medical community because of lived experiences of being taken advantage of | 5.52 (10) |

| Question 7: Most important reason(s) why BIPOC AYAs participate in cancer research or advocacy projects | |

| 1. ”I hope that sharing my story and being an advocate can dispel myths and change a racial minority patient's life; so they won't have to lose parts of themselves or die because they didn't know they had other choices“ | 6.24 (17) |

| 2. ”I do it to make healthcare better for the patients who come behind me“ | 6.03 (20) |

| 3. ”Participating in cancer research or advocacy projects is meaningful and helpful to myself“ | 5.93 (11) |

| 4. ”It makes me happy to feel needed and that my research efforts contribute to society“ | 5.90 (6) |

| 5. ”I want to promote further research for BIPOC teen and young adult cancer patients“ | 5.83 (18) |

| 6. ”Representation matters. I found that I wasn't represented, so I took it upon myself to participate“ | 5.52 (24) |

| Question 8: Most important reason(s) for not participating in cancer research or advocacy projects | |

| 1. ”When the patient has a rare cancer or condition, there are not that many studies targeted at them“ | 4.79 (16) |

| 2. ”I am choosy because I really value my time. And I really value my community's time and racialized people's time“ | 4.72 (21) |

| 3. ”I just haven't come across any cancer research studies for me to participate in, so I jumped on this one when I saw it“ | 4.52 (20) |

| 4. ”It is hard to feel valued without compensation“ | 4.38 (22) |

| 5. ”Participation required the patient advocates to incur financial costs“ | 4.24 (9) |

| 6. ”I do not trust researchers and feel they lack integrity“ | 4.21 (8) |

BIPOC AYA patient experts rated the importance of response options derived from the Round One survey on a Likert scale, ranging from 1, ‘not at all important’, to 7, ‘extremely important’. They also ranked their top three priority responses for each question.

Number of times ranked in top three priorities.

AYA: Adolescent and young adult; BIPOC: Black, Indigenous and People of Color; LGBTQ+: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning.

Data analysis

Investigators computed descriptive quantitative results for mean scores, standard deviations and frequencies of items ranked as top priorities. Table 2 displays the highest rated and highest ranked items in terms of importance for each of the eight central questions. To prepare for Round Three, investigators chose the top-rated and ranked options to create six multiple choice options per central question. Quantitative data analysis for Round Two concluded in less than 1 month (October 2021) and led to the final Round Three survey for consensus decisions.

Round Three: final consensus

Procedure

In the final survey, participants were asked to choose their top three priorities in response to the eight central questions about successful and unsuccessful engagement of BIPOC AYAs. For each question, they had six multiple choice options. To ensure consistent language while retaining meaning, three team members (H Lee, VA Ross and CK Cheung) edited the wording of some items. About half of the participants required two to three email reminders to complete Round Three, which spanned 2 months (October to December 2021). All 32 participants independently completed the final online survey, which did not include open-ended questions. In summary, Round One concluded in August 2021, Round Two concluded in October 2021 and the final Round Three survey was completed in December 2021.

Data analysis

The final consensus among BIPOC AYA e-Delphi experts was determined in Round Three by calculating the frequency with which panelists selected items for their top three priorities (Tables 3 & 4). This also allowed participants an opportunity to revise their judgments from the previous round. Notably, the majority (63%) of items that were ranked among the top three priorities in Round Two were likewise ranked among the top three priorities in Round Three final consensus.

Table 3. . Consensus on best practices in patient engagement across four stages of research among Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult cancer patients and oncology professionals.

| Stage of research | Highest priority best practices |

| Stage 1: ‘Topic selection and research prioritization’ best practices | 1. Engage patients earlier in the process and at higher levels within institutions 1. Identify racial/ethnic inequities in the research topic of interest 2. Employ more BIPOC researchers conducting studies to make participants comfortable 3. Increase sociodemographic diversity among those patients who serve as advocates 3. Communicate the impact of the issue on BIPOC patients in particular when explaining the purpose of the study/project |

| Stage 2: ‘Proposal review: design and conduct of research’ best practices | 1. Identify barriers to recruitment and participation among BIPOC AYA patients and reduce these barriers (e.g., improve outreach, increase methods of interaction/communication and/or help participants feel more safe and secure in the research setting/process) 2. Utilize more BIPOC researchers to conduct the research in order to organically make people feel engaged. Diversity cannot be forced 2. Give BIPOC AYA patients information and access to participation in research studies regardless of their financial situation, social standing, etc. 3. Be honest and authentic and break things down into explanations that patients can easily understand |

| Stage 3: ‘Dissemination and implementation of results’ best practices | 1. Provide results for different levels of comprehension so patients who have a higher level of understanding can access more complicated information without compromising the accessibility of patients who may be younger or otherwise need more simplified explanations 2. Keep it brief and creative and use social media and technology to disseminate in a way that is easy for patients to understand and use 3. Invite a diversity of new BIPOC AYA patient advocates to participate in research and stop using the same patient advocates repeatedly |

| Stage 4: ‘Evaluation of dissemination and implementation strategies’ best practices | 1. Allow patient advocates to provide truly anonymous feedback so they can be completely honest without any concern about repercussions like not being invited to participate again 2. Enable BIPOC AYA patients to actually participate in the conference or meeting and understand and address what they need to get there 3. Compensate BIPOC AYA patients for their time, energy and expertise |

Final consensus was achieved by BIPOC AYA electronic Delphi experts ranking their top three priorities from six multiple choice options for each of the eight central questions. Multiple choice response options were derived from items in the Round Two survey that were the most highly rated and/or most frequently ranked among the top three priorities.

In Stage 1, two items tied for first priority and third priority. In Stage 2, two items tied for second priority.

AYA: Adolescent and young adult; BIPOC: Black, Indigenous and People of Color.

Table 4. . Consensus on highest priority drivers of patient engagement among Black, Indigenous and People of Color adolescent and young adult cancer patient experts.

| Aspect of patient engagement | Highest priority drivers |

| Reasons why ‘transparency–honesty–trust’ is most important core principle for racially minoritized AYA patients | 1. It is important to build trust and be transparent from the beginning in order to avoid doing harm and to ensure that participants feel safe 2. Transparency, honesty and trust are the foundation of everything; researchers cannot do anything without them 3. Trustworthy relationships are especially important for AYAs, who are just coming into their own and need undeniable trust between them and those they interact with 4. If there is trust, BIPOC patients will be more likely to share useful information and not hold anything back |

| Compulsory actions for successful inclusion of BIPOC AYAs' perspectives | 1. Build relationships with communities and listen to patients who are not usually heard 2. Recruit a diverse range of BIPOC patients and let them give actual input into the study 3. Utilize diverse participants in all aspects, not just race (e.g., education, class, age at diagnosis) |

| Reasons for participating in cancer research or advocacy projects | 1. Representation matters. BIPOC AYAs were not represented and so took it upon themselves to participate 2. [Participation] makes healthcare better for the patients who come behind them 3. [Participation] promotes further research for BIPOC AYA cancer patients |

| Reasons for not participating in cancer research or advocacy projects | 1. It is hard to feel valued without compensation 2. Participant's time, community's time and racialized people's time are valuable 3. Have not come across any cancer research studies that are relevant |

Final consensus was achieved by BIPOC AYA electronic Delphi experts ranking their top three priorities from six multiple choice options for each of the eight central questions. Multiple choice response options were derived from items in the Round Two survey that were the most highly rated and/or most frequently ranked among the top three priorities.

In response to “Reasons why ‘transparency–honesty–trust’ is most important core principle for racially minoritized AYA patients” two items tied for second priority.

AYA: Adolescent and young adult; BIPOC: Black, Indigenous and People of Color.

Results

The study results identified key best practices co-developed by BIPOC AYA cancer patients and oncology professionals across four different stages of the research process as identified during a previous call to action (Table 3). In the first stage, ‘topic selection and research prioritization', engaging patients earlier and at higher levels within institutions and identifying racial/ethnic inequities within the relevant research area were highlighted as top priorities. In the second stage, ‘proposal review: design and conduct of research', reducing barriers to recruitment and participation among BIPOC patients, utilizing more BIPOC researchers and providing participants access to information regardless of their financial situation or social standing were emphasized.

For the third stage, ‘dissemination and implementation of results', best practices included providing results at different levels of comprehension, utilizing brief and creative dissemination methods using social media and technology and inviting a diversity of new BIPOC patient advocates (Table 3). In the fourth and final stage, ‘evaluation of dissemination and implementation strategies', enabling anonymous feedback, facilitating participation in conferences or meetings, providing financial compensation for BIPOC patients, and cautioning against using the same patient advocates repeatedly were highlighted.

The importance of transparency–honesty–trust as a set of interrelated core principles when engaging with BIPOC AYAs was stressed as a high-priority driver of patient engagement (Table 4). Participants reported that successful inclusion efforts involved relationship building, diverse recruitment and consideration of the various participant characteristics that intersect with race. Reasons for participating in cancer research or advocacy projects included the need for BIPOC AYA representation and improving healthcare for future patients, whereas reasons for not participating involved the lack of feeling valued without compensation and limited availability of relevant studies.

Discussion

In recent years, there has been a discernible surge in the expectations placed upon BIPOC AYA cancer patients to actively participate in research and advocacy endeavors orchestrated predominantly by White-led organizations. This study aimed to characterize BIPOC AYA cancer patients' experiences of patient engagement in AYA oncology and derive best practices that are co-developed by BIPOC AYAs and oncology professionals.

The current e-Delphi study elucidates the lived experiences related to conventional patient engagement practices and their impact, be it antiracist or biased. This investigation was centered on the embodied knowledge of a panel of experts consisting solely of BIPOC AYA cancer patients (n = 32). Consensus agreement was reached, offering best practices for promoting antiracist research across four stages (Table 4). These best practices have been collaboratively developed by the joint expertise of BIPOC AYAs in the present study and AYA oncology professionals in a previous call to action [21]. Additionally, the BIPOC AYA expert panel has shared reasons behind their choices regarding participation or nonparticipation in oncology research and advocacy. These reasons are tied to their experiences with conventional and purportedly antiracist practices, providing a more comprehensive perspective. These expanded recommendations align with the growing call to involve patient advocates as equal stakeholders in all phases of the biomedical research enterprise [40–42].

Participation among BIPOC AYA patients

BIPOC AYA cancer patients are individuals positioned at different levels within various systems of power [43], and they correspondingly have different reasons for participating or not participating in oncology research and advocacy. In this study, BIPOC AYA expert panelists' reasons for participating in research included feeling a personal call to represent their respective minoritized demographics, believing that their participation would improve healthcare for subsequent patients and promoting further research on BIPOC AYA cancer patients.

BIPOC AYA participants described a few experiences of successful antiracist engagement practices. In one example, the study's recruiters anticipated participants' concerns by providing strong communication to educate prospective participants about the purpose, relevance and impact of the research on the lives of BIPOC AYA cancer patients. Such efforts have been lauded as a means for articulating and fostering shared goals and a collective mission, consistent with existing evidence for BIPOC cancer patients [44].

In another example, the study team empowered BIPOC AYAs by partnering with them to develop realistic plans for the dissemination and implementation of study results. These experiences inspired positive emotions among BIPOC AYAs, deeper involvement, greater interest in cancer research and led them to encourage participation from peers. Researchers might draw upon established practices, such as developing an engagement plan [45] in partnership with BIPOC AYAs to identify reasons for participation and nonparticipation, develop clear terms of engagement, define specific roles and establish safe pathways to work through differences and respond to potential harm.

Nonparticipation among BIPOC AYA patients

Racist experiences in the research process elicited negative emotions and apprehensive involvement, withholding information and complete withdrawal from further engagement among BIPOC AYAs. Negative experiences of patient engagement practices reported by BIPOC AYA expert panelists included lack of transparency regarding the purpose of research, inadequate diversity among researchers and leadership and failure to engage BIPOC patients early in the process. Participants also expressed concerns about overpowering and pressuring behaviors exhibited by some privileged participants as well as insufficient communication about the level of engagement required. These negative experiences underscore the importance of discontinuing such practices and adopting more genuine antiracist approaches to patient engagement.

Genuine (as opposed to token) representation of BIPOC AYA cancer patients in intervention development was described as missing in engagement experiences. Specifically, one BIPOC AYA expert asserted that interventions developed for the broader category of ‘AYA cancer patients' are insufficient. Moreover, several other BIPOC AYA expert panelists endorsed the notion that intervention studies need to specifically target BIPOC AYA cancer patients who experience disparities, while also endorsing the use of social media for outreach to BIPOC AYAs as a whole. This discrepancy highlights the importance of addressing the distinct needs of BIPOC AYA patients as a specific group while keeping in mind that broader interventions may benefit BIPOC AYA patients as well as others. The utility of optimizing social media to expand outreach in these groups is consistent with prior studies showing the efficacy of social media in disseminating cancer-related information among AYA cancer patients [31,46].

Consistent with the antiracist research framework of Goings et al. [25], the majority of BIPOC AYA panelists in the present study suggested that researchers should stay apprised of and respond to the practical challenges that may surface for patient advocates across the project period, such as the changing toll of cancer and its sequelae in their lives [25]. BIPOC AYA cancer patients are an intersectional [47] population characterized by categories of race, social class and gender and their corresponding societal systems that influence experiences of discrimination and disadvantage. Embodied BIPOC AYAs with lived experiences of the intersectional aspects of life after a cancer diagnosis hold experiential knowledge that is critical to the development of research that genuinely responds to their needs [21]. By involving intersectional and embodied BIPOC AYA cancer patients in leadership roles from the earliest stages of setting research priorities and planning research strategies, including but not limited to participant recruitment, investigator teams would have the acumen to troubleshoot otherwise unforeseen obstacles and meet patient advocates where they are.

Transparency–honesty–trust

In the realm of relationships with AYA oncology project teams, BIPOC AYAs in the current study provided insightful perspectives on the presence and absence of transparency, honesty and trust. Several experts on the BIPOC AYA panel shared their encounters with discrimination and marginalization, which subsequently fostered skepticism about the trustworthiness and relevance of their participation in research initiatives rooted within predominantly White-led institutions and organizations. These initiatives were viewed as more likely to perpetuate historical legacies of medical injustice and systemic racism [48] and less likely to improve the problems faced by BIPOC AYA cancer patients. It is incumbent upon researchers to cease discriminatory practices and instead adopt approaches that BIPOC AYAs perceive to be transparent, honest and trustworthy [25].

Limitations & strengths

This study has both limitations and strengths. Although the consensus agreement in the e-Delphi method provides valuable insights from expert opinions, there is potential for bias in developing inferences. The purposive sampling approach of the e-Delphi method may also restrict the range of perspectives. Furthermore, the use of interviews alongside surveys in this study may introduce conformity bias, inhibiting the expression of dissenting views.

Despite these limitations, the study possesses noteworthy strengths. The exclusive inclusion of a BIPOC AYA sample, utilization of an accessible format, integration of expertise from both BIPOC AYA patients and professionals and a rigorous iterative feedback process contributed to the generation of impactful results. The current study exemplifies great potential for the integration of antiracist approaches across all research endeavors, extending beyond the confines of studies centered on racially minoritized cohorts.

Conclusion

Findings from this study are instructional for AYA oncology researchers, clinicians and advocates seeking to correct harmful tokenism and promote genuine strategies for engaging with racially minoritized patients. Genuine antiracist approaches necessitate a conscientious commitment to prioritizing the embodied knowledge and leadership of BIPOC AYAs, who bear the direct impacts of racism within the predominantly White-led American healthcare system. It is incumbent upon researchers and stakeholders to hold themselves accountable to forging substantive collaborations that adeptly respond to the pernicious and evolving nature of racism. Future research should explore reasons underpinning nonparticipation in cancer care among minoritized AYA patients.

Summary points.

Vulnerable Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients face growing demands to engage in research and advocacy initiatives driven by predominantly White-led organizations.

Following a previous call to action from AYA oncology professionals, this study aimed to characterize BIPOC AYA cancer patients' experiences of patient engagement in AYA oncology and derive best practices that are co-developed by BIPOC AYA cancer patients and oncology professionals.

A panel of experts composed exclusively of BIPOC AYA cancer patients (n = 32) participated in an electronic Delphi study to describe their direct experiences and arrive at a consensus opinion on recommendations to advance antiracist patient engagement.

Emergent themes revealed BIPOC AYA cancer patients' positive and negative experiences of conventional and antiracist practices across all phases of research.

In ‘topic selection and research prioritization’, experts prioritized communicating the impact of the research purpose on the lives of BIPOC AYAs.

In ‘proposal review: design and conduct of research’ and ‘dissemination and implementation of results’, experts prioritized providing brief, creative and accessible forms of information to meet the different demands of BIPOC AYAs, some of whom seek complex information and some of whom require simplified explanations.

In ‘evaluation of dissemination and implementation strategies’, experts cautioned against using the same patient advocates repeatedly.

The findings are instructional for healthcare researchers, clinicians and advocates interested in disrupting harmful tokenism and implementing meaningful antiracist research practices.

Future research should further investigate reasons for nonparticipation in cancer care and research among minoritized AYA patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for the framework for patient engagement, which provided an organizing structure for the electronic Delphi study. Additionally, the authors thank T Felder at Cervivor and N Giallourakis at Elephants and Tea for their contribution to participant outreach. The authors also thank J-A Burey of the Black Cancer podcast for participant recruitment and comments that assisted this research.

Footnotes

Author contributions

CK Cheung directed the project and was involved in study conception and design; participant recruitment, data collection and interpretation; manuscript writing, editing and approval and dissemination of results. KA Miller was involved in study conception and design, data interpretation and manuscript writing, editing and approval. TC Goings developed the antiracist research framework employed in data interpretation, advised on the use of her theorizations and contributed to manuscript writing, editing and approval. BN Thomas was involved with data visualization and contributed to participant recruitment, data collection and interpretation as well as manuscript writing, editing and approval. H Lee was involved in participant recruitment, data collection and interpretation as well as manuscript writing, editing and approval. RE Brandon and VA Ross were involved in data interpretation and manuscript editing and approval. T Katerere-Virima and LE Helbling contributed to data collection and interpretation and manuscript approval. CD Simmons was involved in data collection and manuscript approval. JM Causadias, ME Roth, FM Berthaud and LP Jones were involved in manuscript writing, editing and approval. GD Betz led comprehensive literature searches and contributed to manuscript editing and approval. J Carter, SJ Davies, ML Gilman, MA Lewis and G Lopes were involved in manuscript approval. RD Tucker-Seeley was involved in study conception and design, data interpretation and manuscript editing and approval.

Financial disclosure

This study was funded in part by a University of Maryland School of Social Work Competitive Innovative Research Award to CK Cheung. Additionally, H Lee and T Katerere-Virima were supported by the University of Maryland School of Social Work Doctoral Research Assistant Program, and RE Brandon, VA Ross and LE Helbling were supported by the University of Maryland School of Social Work Research Assistant Scholars Program. M Gilman was supported by a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with an interest in or conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Open access

This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2020 (2020). www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf

- 2.Alvarez EM, Force LM, Xu R et al. The global burden of adolescent and young adult cancer in 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Oncol. 23(1), 27–52 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy CC, Lupo PJ, Roth ME, Winick NJ, Pruitt SL. Disparities in cancer survival among adolescents and young adults: a population-based study of 88,000 patients. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 113(8), 1074–1083 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung CK, Nishimoto PW, Katerere-Virima T, Helbling LE, Thomas BN, Tucker-Seeley R. Capturing the financial hardship of cancer in military adolescent and young adult patients: a conceptual framework. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 40(4), 473–490 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Results in an expanded conceptual framework of the financial hardship of cancer to include the contexts of life course development and occupational culture that influence material, psychosocial and behavioral experiences for adolescent and young adult patients.

- 5.Puthenpura V, Canavan ME, Poynter JN et al. Racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic survival disparities in adolescents and young adults with primary central nervous system tumors. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 68(7), e28970 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams SC, Herman J, Lega IC et al. Young adult cancer survivorship: recommendations for patient follow-up, exercise therapy, and research. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 5(1), pkaa099 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: cancer among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) (ages 15–39) (2023). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html

- 8.Bernard DL, Calhoun CD, Banks DE, Halliday CA, Hughes-Halbert C, Danielson CK. Making the ‘C-ACE’ for a culturally-informed adverse childhood experiences framework to understand the pervasive mental health impact of racism on Black youth. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 14(2), 233–247 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svetaz MV, Coyne-Beasley T, Trent M et al. The traumatic impact of racism and discrimination on young people and how to talk about it. In: Reaching Teens: Strength Based, Trauma-Sensitive, Resilience-Building Communication Strategies Rooted in Positive Youth Development (2nd Edition). Ginsburgy K, Brett Z, McClain R (Eds). American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL, USA, 307–328 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karatekin C, Hill M. Expanding the original definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 12(3), 289–306 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syed M, Mitchell LL. Race, ethnicity, and emerging adulthood: retrospect and prospects. Emerg. Adulthood 1(2), 83–95 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond LL, Batan H, Anderson J, Palen L. The polyvocality of online COVID-19 vaccine narratives that invoke medical racism. Presented at: ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New Orleans, LA, USA: (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muffly L, Yin J, Jacobson S et al. Disparities in trial enrollment and outcomes of Hispanic adolescent and young adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 6(14), 4085–4092 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang Y, Yoon H, Kim MT, Park NS, Chiriboga DA. Preference for patient–provider ethnic concordance in Asian Americans. Ethn. Health 26(3), 448–459 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkman AM, Andersen CR, Puthenpura V et al. Impact of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status over time on the long-term survival of adolescent and young adult Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 30(9), 1717–1725 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger N. Enough: COVID-19, structural racism, police brutality, plutocracy, climate change – and time for health justice, democratic governance, and an equitable, sustainable future. Am. J. Public Health 110(11), 1620–1623 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le TK, Cha L, Han H-R, Tseng W. Anti-Asian xenophobia and Asian American COVID-19 disparities. Am. J. Public Health 110(9), 1371–1373 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung CK. Practically speaking: antiracist survivorship advice from and for young BIPOC patients. Elephants Tea Magazine. 8, 6–9 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice & Health. Statement on policing and the pandemic (2020). www.racialhealthequity.org/blog/policingandpandemic

- 20.Hawkins J, Hoglund L, Martin JM, Chiles MT, Tufts KA. Antiracism and health: an action plan for mitigating racism in healthcare. In: Developing Anti-Racist Practices in the Helping Professions: Inclusive Theory, Pedagogy, and Application. Johnson KF, Sparkman-Key NM, Meca A, Tarver SZ (Eds). Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 421–450 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung CK, Tucker-Seeley R, Davies S et al. A call to action: antiracist patient engagement in adolescent and young adult oncology research and advocacy. Future Oncol. 17(28), 3743–3756 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Prompted the current electronic Delphi study and contains detailed recommendations from oncology professionals for advancing antiracist patient engagement in adolescent and young adult oncology research and advocacy that patients in the current study agreed with and elaborated upon to co-develop best practices.

- 22.Cantor J, Sood N, Bravata DM, Pera M, Whaley C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy response on health care utilization: evidence from county-level medical claims and cellphone data. J. Health Econ. 82, 102581 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishkind MC, Shore JH, Bishop K et al. Rapid conversion to telemental health services in response to COVID-19: experiences of two outpatient mental health clinics. Telemed. J. E Health 27(7), 778–784 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Best AL, Roberson ML, Plascak JJ et al. Structural racism and cancer: calls to action for cancer researchers to address racial/ethnic cancer inequity in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 31(6), 1243–1246 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goings TC, Belgrave FZ, Mosavel M, Evans CBR. An antiracist research framework: principles, challenges, and recommendations for dismantling racism through research. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 14(1), 101–128 (2023). [Google Scholar]; •• With its ten foundational principles, this antiracist research framework for dismantling racism in healthcare research was the primary theorization guiding the current electronic Delphi study.

- 26.Kendi IX. How to Be an Antiracist. One World, New York, NY, USA: (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonilla-Silva E. What makes systemic racism systemic? Sociol. Inq. 91(3), 513–533 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dissemination and implementation framework and toolkit (2016). www.pcori.org/impact/putting-evidence-work/dissemination-and-implementation-framework-and-toolkit

- 29.Jones J, Hunter D. Qualitative research: consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 311(7001), 376–380 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe G, Wright G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: issues and analysis. Int. J. Forecast. 15(4), 353–375 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reuman H, Kerr K, Sidani J et al. Living in an online world: social media experiences of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 69(6), e29666 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shang Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: a narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 102(7), e32829 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekayi D, Kennedy A. Qualitative Delphi method: a four round process with a worked example. Qual. Rep. 22(10), 2755–2763 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map. Front. Public Health 8, 1–10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drumm S, Bradley C, Moriarty F. ‘More of an art than a science’? The development, design and mechanics of the Delphi technique. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 18(1), 2230–2236 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ugalde A, Blaschke S-M, Schofield P et al. Priorities for cancer caregiver intervention research: a three-round modified Delphi study to inform priorities for participants, interventions, outcomes, and study design characteristics. Psychooncology 29(12), 2091–2096 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moraitis AM, Seven M, Sirard J, Walker R. Expert consensus on physical activity use for young adult cancer survivors' biopsychosocial health: a modified Delphi study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 11(5), 459–469 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan A, Ports K, Ng DQ et al. Unmet needs, barriers, and facilitators for conducting adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship research in Southern California: a Delphi survey. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 12(5), 765–772 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker KD. Varieties of qualitative research methods: selected contextual perspectives. In: Electronic Delphi Method. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 155–160 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brickley B, Williams LT, Morgan M, Ross A, Trigger K, Ball L. Putting patients first: development of a patient advocate and general practitioner-informed model of patient-centred care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21(1), 261 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies-Teye BB, Medeiros M, Chauhan C, Baquet CR, Mullins CD. Pragmatic patient engagement in designing pragmatic oncology clinical trials. Future Oncol. 17(28), 3691–3704 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liskey D, Cynkin L, Wolfram J. Patients as biomedical researchers. Trends Mol. Med. 28(12), 1022–1024 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Broholm-Jørgensen M, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Pedersen PV. Development of an intervention for the social reintegration of adolescents and young adults affected by cancer. BMC Public Health 22(1), 241 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salamone JM, Lucas W, Brundage SB et al. Promoting scientist–advocate collaborations in cancer research: why and how. Cancer Res. 78(20), 5723–5728 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The value of engagement (2018). www.pcori.org/engagement/value-engagement

- 46.Rost M, Espeli V, Ansari M, von der Weid N, Elger BS, De Clercq E. COVID-19 and beyond: broadening horizons about social media use in oncology. A survey study with healthcare professionals caring for youth with cancer. Health Policy Technol. 11(3), 100610 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev. 43(6), 1241–1299 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rai T, Hinton L, McManus RJ, Pope C. What would it take to meaningfully attend to ethnicity and race in health research? Learning from a trial intervention development study. Sociol. Health Illn. 44(Suppl. 1), 57–72 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]