Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is an obligate intracellular pathogen of significant clinical and public health importance. Yet, a thorough dissection of the molecular basis for its pathogenesis was not made possible until the recent development of a system for genetic transformation. The birth of molecular genetic analysis in Ct has led to the discovery and reassessment of the function of its virulence factors. In this review, we highlight key areas where the application of molecular genetic analysis in Ct has uncovered the function of secreted effector proteins and how these discoveries have provided new insights as to how this remarkable pathogen interacts with host cells and tissues. We also discuss areas where challenges and opportunities remain.

Ever since the discovery of Ct as the causative agent of blinding trachoma in humans and later as the leading cause of sexually transmitted bacterial infections there has been keen interest in understanding the molecular basis for its immunopathogenesis. Ct is a Gram negative obligate intracellular pathogen that infects epithelial surfaces in the conjunctiva, urethra, and endocervix. In women, urogenital serovars of Ct (D-H) can ascend to the upper genital tract where they cause severe damage to the reproductive organs long after the pathogen has been cleared [1]. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) serovars of Ct (L1, L2, and L3) are invasive strains and can be found in the rectal mucosa of both males and females where they invade and reproduce in regional lymph nodes. Recently, LGV serovars have also been associated with outbreaks of rectal infections in men who have sex with men [2]. Ct serovars A-C infect the ocular conjunctiva and are the leading cause of infectious blindness worldwide [3]. Although Ct infections can lead to disease, most individuals infected with C. trachomatis remain asymptomatic, and pathologies can arise from single or recurrent infections [4]. The risk of developing sequalae in response to Ct infections is compounded by the failure of the human host to mount strong, protective adaptive immune memory responses to initial infections [5, 6].

Chlamydia species are obligate endosymbionts of both protist and animal hosts which have co-evolved with eukaryotic hosts for over 600 million years [7]. Several Chlamydia species are pathogenic to humans (such as Ct) and animals and have adapted to specific eukaryotic hosts with the presence of genes that are restricted to each species [8]. Many of these genes encode Type III secretion (T3S) effectors, which are required for the manipulation of host cellular processes [8]. While several T3S effectors have been conserved among Chlamydia species that infect mammals, we predict that the emergence of host-specific effectors likely occurred to colonize tissues and evade host immune responses.

Brief timeline of genetic advances and state of the art-prior to the development of genetic tools in C. trachomatis

Chlamydia species undergo developmental transitions during infection with an environmentally stable, infectious elementary body (EB) form and a replicative reticulate body (RB) form. EBs invade epithelial cells and reside in a membrane-bound compartment that is rapidly modified by the pathogen to create an “inclusion”. Within this vacuole, the EB form transitions to the RB form and begins to replicate. At this stage, the inclusion expands rapidly and RBs asynchronously differentiate back to the EB form to fuel the next round of infections. Under in-vitro stress conditions, RBs can enter into an altered and non-replicative form referred to as a persistence state. Upon removal of the stress, RBs revert back to their replicative state (reviewed in [9]). By the end of the infectious cycle (48-72h in cell culture) the host cell lyses or the entire inclusion is extruded from the infected cell [10-12].

The first clues as to how Ct avoids destruction by the endolysosomal system came from the discovery by Rockey, Hackstadt and colleagues of a protein that decorated the inclusion membrane [13]. This protein had a hydrophobic bilobed motif of 50-60 amino acids that was subsequently found to be shared among other inclusion membrane (Inc) proteins [14, 15]. Inc proteins are now recognized as key players in regulating interactions between Ct and its host. The publication of the genome of C. trachomatis in 1998 opened up the era of functional genomics in Ct, when the complete blueprint of the organism revealed an abundant repertoire of putative Inc proteins [16*].

Early attempts at identifying Ct virulence proteins focused on potential substrates of the T3S system by expressing full length and the N-terminal regions of Ct proteins in heterologous bacterial systems and determining if they were sufficient to drive the T3S-dependent export of reporter proteins in Yersinia, Shigella or Salmonella [17-20]. Other approaches relied on the conservation between yeast and mammals to identify Ct proteins that could drive phenotypes that were consistent with the manipulation of eukaryotic cellular processes [21]. Additional functional approaches included the generation of immunoreagents to assess the localization of all Ct proteins within infected cells [22-24]. The end result of these diverse experimental strategies was the identification of a defined set of proteins, including Incs, that likely interfaced with proteins in the host cell cytoplasm.

Yet, in the absence of a method to specifically disable these proteins it was difficult to unequivocally ascertain their function during infection. Early attempts at performing functional analysis included the microinjection of effector-specific antibodies. For instance, the role of IncA as a factor that drives the fusion of inclusions was underscored by the observation that cells that had been microinjected with anti-IncA antibodies displayed large numbers of unfused inclusions upon infection [25]. These observations have been supported by the identification of Ct clinical isolates that lack IncA and form unfused inclusions [26]. Mutagenesis of incA has also provided additional evidence to corroborate these findings [27*, 28**, 29*]. Alternative approaches that became standard to identify host cell targets of effector proteins also included co-affinity purification schemes or yeast two hybrid screens (i.e. [30-36]). The relevance of such interactions was then tested by disrupting the function of the host targets by expression of dominant negative forms of these proteins or by RNA interference. If blocking the function of the host protein led to an impact on bacterial replication or survival, it was inferred that the associated effector was also important for virulence. Such interpretations are fraught with caveats, as we will point out in greater detail below, but in the absence of tools to genetically manipulate Chlamydia species this remained one of the few viable options to characterize putative virulence factors.

Forward and reverse genetics approaches in C. trachomatis

For decades after they were first cultured in the laboratory, Chlamydia species remained stubbornly recalcitrant to molecular genetic manipulation. Early attempts at genetic transformation yielded mixed results until Clarke and colleagues provided the first evidence of stable maintenance of a shuttle plasmid into an LGV strain of Ct [37**]. Despite the lag in the development of a transformation methods for Ct, significant advances have been made in the application of genetic approaches to dissect various aspect of Ct biology. For instance, by leveraging natural lateral gene transfer among Ct, it became possible to apply genetic recombination strategies to link chemically induced mutations to specific traits [38, 39]. In this fashion, banks of mutants could be assembled and used for forward and reverse genetic applications to identify phenotypes of interest and the underlying causal mutations [28**, 40**, 41**, 42]. As newer molecular genetic tools were developed, in particular the use of group two introns (TargeTron) and allelic exchange for targeted gene disruption, it became increasingly feasible to generate loss-of-function mutations [27*, 43*,44*] and complement them with plasmids, thus satisfying Falkow’s Molecular Kochs’ postulates [45] and enabling a molecular characterization of Ct virulence factors.

Invasion-associated C. trachomatis effectors

The best characterized Ct effectors are those translocated during the initial stages of invasion. There are at least five unique factors that are translocated during EB attachment and invasion of the target host cell, including the effectors Tarp, TmeA, TmeB, TepP and TaiP. Tarp is a multidomain protein that can nucleate actin filaments and recruit and activate the host cell Arp2/3 complex (an actin nucleator complex that promotes formation of branched actin filaments) through tyrosine phosphorylated repeats to promote actin polymerization at bacterial entry sites [46*-48]. Through the use of mutant strains expressing tarP alleles carrying in-frame deletions of the Tyr phosphorylation and F-actin binding domains, these regions were shown to be required for TarP-dependent invasion [49]. However, while TarP clearly plays a role in invasion, tarP mutants only exhibit a partial reduction in invasion efficiency, suggesting that additional Ct factors enable entry into epithelial cells [49].

Another effector implicated with the process of invasion is TmeA. Loss of tmeA or tarP results in a moderate decrease in invasion efficiencies of host cells [49-51]. A double tmeA tarP mutant strain exhibits an additive effect on Ct invasion efficiency, indicating that both secreted effectors act synergistically in orchestrating Ct entry into host cells [51]. Proximity labeling experiment using TmeA-BirA in transfected cells and TmeA-APEX chimeras expressed in Ct, identified N-WASP as a host factor that interacts with TmeA [51]. The interaction of TmeA with N-WASP is sufficient to activate Arp2/3 dependent actin polymerization [51]. Interestingly, TarP can also induce Arp2/3 dependent actin polymerization via recruitment of factors that activate the small regulatory GTPase Rac1 [52]. In this fashion, both TmeA and TarP promote actin polymerization independently to promote Ct entry into host cells [51]. In addition, Formin 1, another actin nucleating factor that is required for rapid actin polymerization at sites of entry, is recruited to bacterial entry sites in a TarP dependent but TmeA independent manner, suggesting that TarP also promotes actin polymerization by multiple mechanisms [53].

TepP, like TarP, is a Ct effector secreted early during infection that is phosphorylated at tyrosine residues by Src kinases [54*, 55]. However, tepP deficient mutants are not defective for the invasion of mammalian cells but they display decreased replication during infection of endocervical epithelial cells [55]. TepP associates with CrkI/II, CrkL, GSK-3, and PI3K at nascent inclusions and loss of tepP results in increased expression of several cytokine genes such as IL6 and CXCL3 [54*, 55]. Paradoxically, over expression of tepP leads to an increase in the expression of type I IFN genes IFIT1 and IFT2 [54*, 55]. TepP activates PI3K and PI3K activity is required for TepP dependent induction of IFIT1 and IFT2 gene expression [55]. How TepP promotes activation of PI3K and Crk and GSK binding remains to be determined, however, TepP association with these factors is probably necessary for optimal Ct fitness in cervical epithelial cells and to modulate the transcription of genes associated with type I IFN responses [55]. Like TarpP, TepP is likely to perform multiple functions that can be genetically separable. Indeed, TepP co-opts the function of the F-actin regulator EPS8 to disassemble tight junctions of polarized epithelial cells to further enhance the invasion by EBs, presumably by providing access to additional receptors [56]. In addition, endometrial organoids (EMOs) infected with a tepP mutant significantly increased neutrophil recruitment to EMOs relative to EMOs infected with wild type Ct [57]. These results suggest that TepP also functions in limiting the influx of neutrophils at sites of infection, possibly through its role in dampening expression of IL-6 and CXCL3. The role of TepP in Ct infections is further underscored by the observation that C. muridarum tepP mutants are severely attenuated in their ability to ascend to upper genital tract after vaginal infections [56].

TaiP (translocated ATG16L1 interacting protein) was originally identified as a Ct protein with a functional T3S signal that is highly enriched in EBs and localizes to the cytoplasm of host cells [19, 58-60]. Based on these observations TaiP has been proposed to be secreted early in infection [60]. TaiP unlike TarP and TepP is not phosphorylated upon translocation [60], and taiP mutants are internalized less effectively and are attenuated for growth in Hela cells [60]. TaiP binds the autophagy related protein 16-1 (ATG16L1) through an ATG16L1-binding motif in its carboxy tail domain [61]. ATG16L1 restricts inclusion growth through its association with the transmembrane protein TMEM59 rather than by its well-known role in promoting lipidation of the microtubule-associated and autophagy promoting protein LC3 [61]. TaiP binds to the WD40 domain of ATG16L1 and disrupts ATG16L1 association with TMEM59 leading to the rerouting of Rab6 (Golgi associated GTPase) positive vesicles to the inclusion [61]. These results suggest that Rab6-mediated membrane trafficking is important for inclusion growth and that Ct utilizes a unique effector for the acquisition of nutrients. The role for TaiP in promoting invasion remains to be further characterized.

Inclusion membrane dynamics

The membrane of the inclusion enables the bidirectional flow of nutrients and metabolic waste while limiting the engagement of cytoplasmic innate immune sensors. Inc proteins are predicted to perform many of these functions either by engaging the membranes of host organelles adjacent to inclusions, regulating protein and membrane trafficking, or by providing structural integrity to the inclusion (reviewed in [62**]). Inc proteins may also act as hubs for protein-protein interactions that control signaling cascades important for bacterial fitness within infected cells and tissues. One of the challenges in studying Inc proteins is that any one Inc likely performs multiple functions (Figure 1). This was first predicted by findings from proteomic screens for host binding partners of Inc proteins, which often yielded multiple high confidence binding partners for any one Inc [35**]. The modular and multi-functional nature of Incs has further been evidenced through molecular genetic approaches as detailed below.

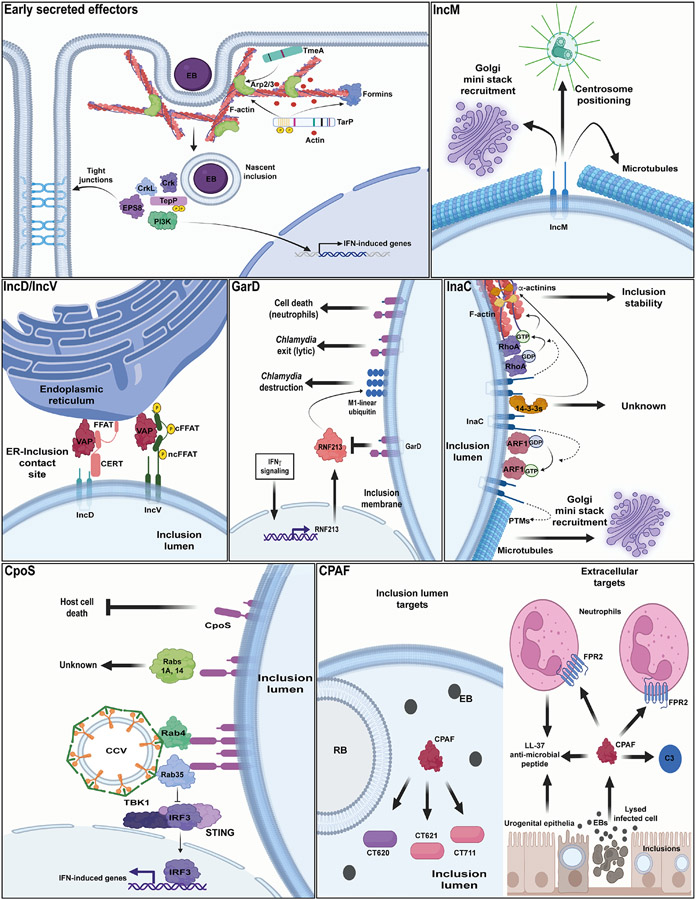

Figure 1. The multiple roles of Ct effectors.

Early secreted effectors. TmeA, TarP, and TepP are secreted early in infection of host cells. TmeA localizes to host plasma membranes where it initiates signaling cascades that leads to activation and retention of the Arp2/3 complex near Ct EB entry sites. TarP is phosphorylated at tyrosine residues upon translocation into host cells. TarP mediated signaling events in coordination with TmeA also leads to recruitment of Arp2/3 and formation of F-actin networks at Ct EB entry sites. TepP is also phosphorylated at tyrosine residues early in infection and functions to recruit Crk, CrkL, PI3K, and Eps8 to Ct nascent inclusions. TepP dependent recruitment of PI3K induces the transcription of type I interferon (IFN)-induced genes. TepP dependent recruitment of Eps8 results in breakdown of epithelial tight junctions. IncD and IncV. IncD interacts with the human ceramide transfer protein CERT which binds to the ER-resident protein VAP through a FFAT motif. Formation of IncD and CERT might facilitate transport of ceramides to the inclusion membrane. IncV independently binds to VAPs through non-canonical (ncFFAT) and canonical (cFFAT) FFAT motifs present in its C-terminus. Phosphorylation of IncV by host protein kinases is necessary for IncV interactions with VAPs. Both IncD and IncV play roles in promoting tethers (contact sites) at the inclusion and ER interphase. IncE is required for recruitment of sorting nexins and syntaxins to the inclusion. Sorting nexins play a role in promoting formation of fibers that emanate from the inclusion during infection of human host cells. The functional significance for the recruitment of syntaxins to the inclusion remains unexplored. GarD protects Ct inclusions from cell autonomous IFNγ mediated immunity. Gard shields inclusions from targeted ubiquitination by the IFNγ inducible E3 ligase RNF213 in human epithelial cells. Infection of IFNγ primed host cells with garD deficient Ct triggers ubiquitination of the inclusion with M1-linked linear polyubiquitin chains and subsequent bacterial degradation. The Ct serotype D homolog of GarD (CT135) is also linked to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and cytotoxicity in primary murine neutrophils. InaC interacts with multiple 14-3-3 proteins during infection of human host cells. The function of these interactions remain unknown. InaC also promotes activation of the small GTPase ARF1 (ARF1 GTP) in early stages of Ct infection of host cells. Both InaC and activated ARF1 promote posttranslational modifications (PTMs) (acetylation and detyrosination) of microtubules present at the periphery of the inclusion. Modified microtubules are necessary for repositioning of Golgi mini stacks around the inclusion periphery. At later stages of infection, InaC promotes activation of the small GTPase RhoA which is recruited to the inclusion in an InaC independent manner. Activated RhoA (RhoA-GTP) inhibits ARF1 activation and subsequent PTMs of microtubules while ARF1-GTP promotes further activation of RhoA. As levels of activated RhoA increase, activated RhoA promotes formation of F-actin scaffolds around the inclusion which provides stability to the inclusion. CpoS interacts with multiple human Rab GTPAses during infection of human cells. The interaction of CpoS with both Rab4 and Rab35 mediates the recruitment of clathrin coated vesicles (CCVs) to the inclusion, while the interaction of CpoS with Rab35 is required for Ct to block activation of STING/IRF3 mediated transcription of IFN-induced genes. The functional significance of the interactions between CpoS and Rabs 1A and 14 remains to be further characterized. CpoS also blocks activation of host cell death programs by an unknown mechanism and this activity is uncoupled from its interactions with Rab GTPases. CPAF is a secreted protease that promotes the degradation of both Ct proteins and host extracellular proteins. CPAF is secreted into the lumen of Ct inclusions where it targets the Ct secreted effectors CT620, CT621, and CT711. CPAF targets extracellular proteins presumably when released during lytic exit of Ct from host cells. CPAF can cleave the formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) present at the surface of neutrophils and it can also cleave the antimicrobial peptide Ll-37 which is produced by urogenital epithelial cells and neutrophils. In addition, CPAF can also cleave the complement factor C3. This Figure was generated with BioRender.com.

The N and C-terminal domains of Inc proteins are exposed to the host cell cytosol, where they have the potential to interact with multiple host proteins essential for bacterial survival. One such example is the inclusion membrane protein IncS, which is required early in the Ct developmental cycle of both Ct and C. muridarum (Cm) [63**]. IncS is likely essential since incS null strains cannot be recovered, unless they are generated in the presence of conditionally expressed incS [63**]. The number of RBs detected within Ct and Cm inclusions drastically decrease in the absence of IncS, suggesting that IncS is necessary for EB to RB developmental transitioning [63**]. This work is a significant advance in the field as it describes how to generate targeted conditional mutant strains for characterizing the function of essential effectors. The next step will be to elucidate the mechanism by which IncS facilitates this early developmental transition.

During Ct infection, Ct traffics to the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) where Inc proteins mediate interactions with organelles, centrosomes, and cytoskeletal proteins (reviewed in [62**]). One consequence of these interactions is disruption of the cell cycle as evidenced by the presence of multinucleated cells in Ct infected cells [64-66]. This phenomenon is mediated in part by IncM (Inc mediating multinucleation) [67]. Epithelial cells display fewer multinucleated cells when infected with incM null strains [67]. IncM also contributes to the positioning of centrosomes relative to the host cell nucleus and the repositioning of Golgi ministacks around the inclusion periphery [67]. Additionally, IncM stabilizes a network of microtubules that surround the inclusion, but it remains unclear whether IncM directly interacts with microtubules [67]. The direct interactions between IncM and microtubules could be a mechanism by which IncM facilitates centrosome positioning and Golgi dispersion around the inclusion.

Additional Inc proteins also facilitate interactions between Ct and host organelles. For instance, IncV and IncD facilitate the tethering of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the inclusion membrane to form ER-Inclusion membrane contact sites (MCSs) [35**, 68*, 69]. Formation of these MCSs at the ER-inclusion interface mediate the transfer of lipids to the inclusion [68*, 70]. IncV interacts with the proteins VAPA and VAPB which are normally enriched at ER MCSs [69]. These interactions are dependent on two FFAT motifs present in IncV as demonstrated by molecular genetic approaches. GFP-tagged VAPA and VAPB co-IP with Flag-tagged IncV expressed in Ct during infection and this interaction was dependent on both its canonical FFAT motifs [69]. IncV is also phosphorylated by the protein kinase CK2 and this phosphorylation is necessary for its interactions with VAPs and for assembly of the ER-inclusion MCS [71]. Furthermore, the expression of IncV variants with amino acid substitutions in S345A, S346A, and S350A in Ct incV mutant strains showed that all three serine residues which are part of the CK2 recognition site in the C-terminal domain of IncV are necessary for the recruitment of CK2 to the inclusion membrane [71]. While many FFAT domain proteins contain acidic tracts that are required for interactions with VAPS, IncV’s phosphoserine rich tracts may mimic these acidic patches [71]. Interestingly, replacing the IncV serine patches with acidic amino acids and expression of these variants in incV mutant strains prevents its translocation to the inclusion membrane [71]. These results suggest that the serine tracts in IncV ensure proper secretion of IncV and subsequent phosphorylation by host cell kinases promote interactions with eukaryotic VAPs [71]. While these observations suggest that IncV plays a role in ER-Inclusion MCS formation, a Ct mutant strain lacking incV only exhibits a moderate decrease in recruitment of VAPS to ER-inclusion MCSs suggesting that additional factors contribute to formation of MCS at the inclusion [69].

Identification of new Chlamydia effectors by forward genetic approaches

The Ct protein CT813 was originally identified as an inclusion membrane protein based on its localization by indirect immunofluorescence [72]. It was subsequently renamed InaC (Inclusion associated Actin) when a mutant in this gene was identified from a screen of mutagenized Ct strains that failed to recruit F-actin scaffolds to the inclusion membrane [28**]. InaC was also observed to interact with ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) GTPases, which are major regulators of intracellular trafficking [73], and to be necessary for repositioning of Golgi ministacks around the inclusion [28**, 74] with Arf1 and Arf4 recruitment to inclusion membranes being lost in inaC mutants [28**, 74]. InaC promotes activation of Arf GTPases which in turn leads to the acetylation and detyrosination of microtubules adjacent to the inclusion membrane [74]. These microtubule modifications promote Golgi mini stack repositioning around the inclusion [74]. InaC also promotes activation but not recruitment of the small GTPase RhoA (a regulator of the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in [75])) which has previously been shown to be required for the formation of scaffolds of actin around the inclusion [66, 67*]. The scaffolding of actin and of modified microtubules around the inclusion occur at different stages of the Ct lifecycle. Modified microtubules are primarily assembled around the Ct inclusion around 24 hours post infection (hpi) whereas recruitment of actin scaffolds begins at 32 hpi [76, 77*]. The temporal regulation of actin and microtubule assembly around the inclusion is also InaC dependent. Small GTPases cycle between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state. InaC dependent activation of Arf1 (Arf1-GTP) occurs early in infection (~16 hpi). Midway through infection (~24 hpi), RhoA is recruited to the inclusion independently of InaC where it proceeds to inhibit Arf1 activation. Inactivation of Arf1 concomitantly leads to an InaC dependent activation of RhoA, [77*]. This complex coordination of the activity of host cell small GTPases (Arf1 and RhoA) by a single Ct effector highlights the modular and multifaceted activities inherent to Ct effectors for fine tuning rearrangements of the host cytoskeleton during infection. Importantly, the use of engineered Ct strains was instrumental for dissecting these functional intricacies since relying on pharmacological inhibitors of cytoskeleton assembly can easily obfuscate results due to the pleiotropic effects they elicit. Unresolved questions as to the function of InaC include its role in the recruitment of 14-3-3 proteins to the inclusion membrane [28**], a function that has also been ascribed to IncG [30].

CpoS is another Inc with multiple roles during Ct infection of host cells. CpoS (Chlamydia promoter of Survival) was identified in a screen for Ct mutants that induced enhanced cytotoxicity in Hela and THP-1 cells [29*]. CpoS binds to Rab small GTPases, which are regulators of membrane trafficking between intracellular compartments, suggesting that CpoS mediates interactions with vesicular trafficking pathways [29*, 78-79]. These GTPases are not recruited to the inclusion membrane of cpoS mutants [29*, 79] and the recruitment of transferrin and the Mannose 6 Phosphate Receptor to the inclusion is diminished in host cells infected with a cpoS mutant indicating that CpoS mediates interactions with clathrin-dependent transport pathways from the plasma membrane and trans-Golgi network [79]. CpoS possesses a coiled-coil domain at its C-terminus domain [69]. Ectopic expression of a CpoS variant carrying an amino acid substitution in its coiled-coil domain (L120D) in a cpoS null background suggests that the C-terminal region of CpoS is necessary for binding to Rab GTPases [79]. While the repurposing of vesicle trafficking by CpoS might be necessary for nutrient acquisition by Ct, these findings should be interpreted in the context of the severe growth phenotype of cpoS mutants and the rapid onset of death in cells infected with these mutants [29*, 80], and that mutant alleles of cpoS that cannot recruit Rab GTPases still protects the host cell from death [81]. Loss of cpoS also results in a significant increase in the transport of the innate immune receptor STING from the ER compartment and the hyperactivation of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) [29*]. The same cpoS alleles that fail to recruit Rab GTPases are also unable to block the enhanced translocation of STING, suggesting that one prominent role of co-opting Rab GTPases is to dampen innate immune signaling. Interestingly, while the expression of ISGs is not sufficient to induce death in cells infected with cpoS mutants, STING is still partially required to induce cell death [29*]. This is consistent with a role of STING in controlling the activation of Type I IFNs and cell death through distinct mechanisms (reviewed in [82]). How these activities impact the expression of IFN-regulated genes or protection from cell death remains to be better characterized but will be possible through the use of separation of function cpoS alleles.

Forward genetic screens of Ct mutant strains also resulted in the identification of GarD (gamma resistance determinant) as an Inc required for Ct to protect itself from INFγ induced antimicrobial host defenses [83*]. In infected human cells, Cm is susceptible to INFγ mediated clearance while Ct is not, indicating that Ct actively attenuates human INFγ based defenses [83*, 84]. In a forward genetic screen for INFγ sensitive Ct mutants, strains with nonsense and loss of function mutations in garD (CTL0390/CT135) were identified that displayed attenuated growth in INFγ primed A549 cells [83*]. Inclusions of garD deficient strains were targeted for INFγ dependent M1-linked ubiquitination by the E3 ligase RNF213 [83*]. Cells infected with garD mutants also recruited the M1-linked ubiquitin binding adaptor proteins OPTN, NPDP52, TAX1BP1 and to a lesser extent the ubiquitin like proteins LC3 and GABARAPs to the inclusion membrane [83*]. The recruitment of xenophagy receptors to garD mutant inclusions suggest that garD deficient strains might be routed for destruction through lysosomal degradation since lysosomal LAMP1 also co-localizes with garD mutant inclusions [83*]. Some questions remain to be addressed such as identifying the targets recognized by RNF213, the mechanism by which RNF213 is directed to the Chlamydia inclusion, and weather RNF213 mediated immune defenses are deployed against other intracellular pathogens. GarD also plays additional roles such as promoting exit of Ct from host cells via lysis [85]. Interestingly, GarD dependent host cell lysis requires STING, which is also partly required for host cells to induce cell death during infection of epithelial cells with cpoS deficient strains [29*, 85]. In addition, GarD in Ct serovar D (CT135) has also been linked to activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and cytotoxicity in infected murine primary neutrophil cells, suggesting that GarD and its homologs can also promote Ct immune evasion by neutralizing neutrophil host defenses [86*]

Additional genetic screens have helped identify factors required for Chlamydia to evade INFγ mediated immunity. Screening of C. muridarum mutagenized with EMS for example identified 31 IFNγ sensitive mutants, including a strain with a missense mutation in a gene encoding the putative C. muridarum inclusion membrane protein TC0574 which was linked to sensitivity to IFNγ treatment [87]. Inclusions of strains carrying mutations in TC0574 lyse in the presence of IFNγ and elicit host cell death which is dependent on host cell caspases [87]. The mechanism by which TC0574 protects C. muridarum from IFNγ mediated clearance remains to be elucidated. IFNγ also triggers Chlamydia species to enter a viable but non-replicating state in vitro called persistence [reviewed in [9]). Screens of chemical mutants have also been employed to identify Ct factors necessary for Ct to reactivate from IFNγ induced persistence. From these screens, trpB, and genes previously unlinked to persistence such as CTL0225, CTL0694, and ptr were linked to Ct ability to exit from a persistence state [88, 89]. trpB encodes the beta subunit of tryptophan synthase and has been linked to Ct persistence [41**], while CTL0225 and CTL0694 encode a putative membrane protein and an oxidoreductase, respectively. The mechanisms by which the latter promote reactivation from persistence remains unknown. Ptr-deficient mutants showed a reduction in the generation of infectious progeny after exiting from IFNγ induced persistence [89]. Interestingly, Ptr is a putative protease that is secreted into the inclusion lumen [89]. Considering that persistence is thought to be a stress response triggered by amino acid starvation (reviewed in [9]), Ptr might be playing a role in scavenging amino acids from the lumen of the Ct inclusion thereby aiding in the recovery of Ct from a persistent state.

Reassessing the function of proteases and the cryptic plasmid

Prior to the development of molecular genetic tools, multiple approaches had been implemented to assign a function to Chlamydia effectors and other potential virulence factors. These included implying functions from predicted and confirmed biochemical activities, or their impact on mammalian cells following ectopic expression. While in many instances these approaches have identified bonafide substrates and functions of Chlamydia effectors, there are caveats given that overexpressed effectors, for instance during transient transfections, may not reflect the true localization or function of the native proteins during infection given the differences in stoichiometry, spatial constraints in relation to inclusions, post translational modifications, or by activities provided by other Chlamydia factors present during infection. An example of the challenges associated with elucidating the function of effectors solely based on enzymatic activities is illustrated by the secreted protease CPAF. Numerous studies suggested that CPAF modulated multiple processes given the many substrates identified in vitro (reviewed in [90]). However, in retrospect caution in the interpretations of these results was warranted given that CPAF’s activity is difficult to inhibit and can cleave substrates during sample preparation [91]. The identification of a C. trachomatis cpa (CPAF) null strain provided genetic evidence that many potential CPAF substrates may not be targeted for proteolysis during Ct’s intracellular stage [92] although this observation does not preclude the possibility that some of the identified targets are cleaved at a different stage during infection.

Renewed efforts at identifying CPAF substrates using cpa null strains included a comparative analysis of proteomes from Hela cells infected with wild type Ct and a cpa null strain which revealed 10 Ct proteins whose abundance increased during infection with a cpa null strain [93]. Of these, the T3S substrates CT620 and CT711 appear to be proteolytically processed in wild type Ct cells [93]. CT620 and CT621 (another T3S substrate) also localize to the inclusion lumen where CPAF has also been shown to localize [94, 95]. These results suggest that CT620, CT621, and CT711 are potential bacterial in vivo targets of CPAF. Mutant cpa strains also support a role for CPAF in degrading targets that are not in the host cell cytoplasm, presumably after being released during lytic exit of Ct from host cells. For instance, CPAF cleaves formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) present on the surface of neutrophils to block the activation of neutrophils and NETosis [96**]. CPAF can also cleave the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 produced by urogenital epithelia and recruited neutrophils as well as complement factors C3 and factor B [97, 98]. Targeting of these extracellular factors may be linked to CPAF’s role in promoting Ct survival in the upper genital tract [99].

Native plasmids of both Ct and Cm contribute to infectivity and virulence in several animal models of Chlamydia infection [100-103]. Chlamydia strains harboring plasmids with pgp3 deletions are as attenuated in virulence as plasmidless Chlamydia strains [104, 105]. Notably, pgp3 deficient C. muridarum is less invasive in the lower genital tract and fails to ascend to murine upper genital tracts [105]. C. muridarum pgp3 deficient strains are also defective in colonization of the gastrointestinal tract in infected mice [106]. The mechanism by which pGP3 promotes C. muridarum colonization of genital and intestinal tracts requires further characterization, especially with the aid of pgp3 deficient strains. Recombinant pGP3 (rpGP3) binds and neutralizes the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin LL-37, which is also targeted by CPAF hinting to synergistic functions between the two virulence factors [97, 107-108].

Challenges for Chlamydia effector biology and analysis

The application of a full spectrum of genetic tools in Chlamydia, including tools for generating conditional null strains for identifying the function of essential effectors (i.e [42, 63]) will invariably increase the rigor of future molecular analysis of effector proteins and their role in infection. Given the emerging theme that Chlamydia effectors perform multiple functions (Figure 1), the generation of separation of function mutants will be essential to understand whether these functions are acting independently from each other or have evolved to function synergistically. Separation of function mutants will also aid in defining which functions and pathways are most critical for pathogenesis. Similarly, it will be important to use Chlamydia effector mutants in the context of infection of cells defective in the proposed pathways targeted by the effector to distinguish between indirect effects resulting from the disruption of a major host cellular pathways and those perturbed by the effector. It would not be surprising if virulence phenotypes are not as penetrant as first envisioned and that multiple effectors act in a coordinated manner. In this case, mutant strains bearing multiple null alleles of effectors in various combinations and genetic screens such as synthetic lethal screens will be useful in uncovering synergistic interactions among effectors. The analysis of Chlamydia effector proteins will also benefit from new cellular models of infection that better mimic the cervical and uterine epithelium and animal models that are closer to both the acute and chronic stages of infection, as many relevant phenotypes will not become apparent until infections with mutants are performed in the most relevant tissues.

Highlights.

Genetic approaches have significantly accelerated the discovery and characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis effector proteins.

Separation-of-function mutants in Chlamydia effectors are needed to clarify the multiple roles of effectors and their individual contributions to virulence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported AI134891.

Footnotes

CRediT author statement

Bastidas Robert: Writing, Reviewing and Editing. Valdivia Raphael: Writing, Reviewing, and Editing.

References and recommended reading

* of special interest.

** of outstanding interest.

- 1.O’Connell CM, Ferone ME: Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infections. Microb. Cell 2016, 3:390–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward H, Alexander S, Carder C, Dean G, French P, Ivens D, Ling C, Paul J, Tong W, White J, et al. : The prevalence of lymphogranuloma venereum infection in men who have sex with men: results of a multicenter case finding study. Sex. Transm. Infect 2009, 85:173–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitcher JP, Srinivasan M, Upadhyay MP: Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull. World Health Organ 2001, 79:214–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillis SD, Owens LM, Marchbanks PA, Amsterdam LF, Mac Kenzie WR: Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 1997, 176:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loomis WP, Starnbach MN: Chlamydia trachomatis infection alters the development of memory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177:4021–4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fankhauser SC, Starnbach MN: PD-L1 limits the mucosal CD8+ T cell response to Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol 2014, 192:1079–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horn M, Collingro A, Schmitz-Esser S, Beier CL, Purkhold U, Fartmann B, Brandt P, Nyakatura GJ, Droege M, Frishman D, et al. : Illuminating the evolutionary history of Chlamydiae. Science 2004, 304:728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collingro A, Tischler P, Weinmaier T, Penz T, Heinz E, Brunham RC, Read TD, Bavoil PM, Sachse K, Kahane S, et al. : Unity in variety--the pan-genome of the Chlamydiae. Mol. Biol. Evol 2011, 28:3253–3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panzetta ME, Valdivia RH, Saka HA: Chlamydia Persistence: A Survival Strategy to Evade Antimicrobial Effects in-vitro and in-vivo. Front. Microbiol 2018, 9:3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelrahman YM, Belland RJ: The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2005, 29:949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J: Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2016, 14:385–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hybiske K, Stephens RS: Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007, 104:11430–11435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockey DD, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T: Cloning and characterization of a Chlamydia psittaci gene coding for a protein localized in the inclusion membrane of infected cells. Mol. Microbiol 1995, 15:617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bannantine JP, Rockey DD, Hackstadt T: Tandem genes of Chlamydia psittaci that encode proteins localized to the inclusion membrane. Mol. Microbiol 1998, 28:1017–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T: Identification and characterization of a Chlamydia trachomatis early operon encoding four novel inclusion membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol 1999, 33:753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*. Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, et al. : Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 1998, 282:754–759. Landmark paper showing the sequence of the first Chlamydia genome which ushered a new era of molecular genetics in Chlamydia. The whole genome sequencing of a C. trachomatis urogenital strain showed the presence of a type III secretion system and a streamlined genome in which several biosynthetic pathways had been purged from the genome and provided clues as to how these organisms have adapted as intracellular pathogens.

- 17.Fields KA, Hackstadt T: Evidence for the secretion of Chlamydia trachomatis CopN by a type III secretion mechanism. Mol. Microbiol 2000, 38:1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subtil A, Parsot C, Dautry-Varsat A: Secretion of predicted Inc proteins of Chlamydia pneumoniae by a heterologous type III machinery. Mol. Microbiol 2001, 39:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subtil A, Delevoye C, Balañá M-E, Tastevin L, Perrinet S, Dautry-Varsat A: A directed screen for chlamydial proteins secreted by a type III mechanism identifies a translocated protein and numerous other new candidates. Mol. Microbiol 2005, 56:1636–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho TD, Starnbach MN: The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium-encoded type III secretion systems can translocate Chlamydia trachomatis proteins into the cytosol of host cells. Infect. Immun 2005, 73:905–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisko JL, Spaeth K, Kumar Y, Valdivia RH: Multifunctional analysis of Chlamydia-specific genes in a yeast expression system. Mol. Microbiol 2006, 60:51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma J, Zhong Y, Dong F, Piper JM, Wang G, Zhong G: Profiling of human antibody responses to Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital tract infection using microplates arrayed with 156 chlamydial fusion proteins. Infect. Immun 2006, 74:1490–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Chen D, Zhong Y, Wang S, Zhong G: The chlamydial plasmid-encoded protein pgp3 is secreted into the cytosol of Chlamydia-infected cells. Infect. Immun 2008, 76:3415–3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Zhang Y, Lu C, Lei L, Yu P, Zhong G: A genome-wide profiling of the humoral immune response to Chlamydia trachomatis infection reveals vaccine candidate antigens expressed in humans. J. Immunol 2010, 185:1670–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackstadt T, Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Fischer ER: The Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell. Microbiol 1999, 1:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suchland RJ, Rockey DD, Bannantine JP, Stamm WE: Isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis that occupy nonfusogenic inclusions lack IncA, a protein localized to the inclusion membrane. Infect. Immun 2000, 68:360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*. Johnson CM, Fisher DJ: Site-specific, insertional inactivation of incA in Chlamydia trachomatis using a group II intron. PLoS ONE 2013, 8:e83989. First description of targeted mutagenesis in Chlamydia using group II homing introns.

- 28**. Kokes M, Dunn JD, Granek JA, Nguyen BD, Barker JR, Valdivia RH, Bastidas RJ: Integrating chemical mutagenesis and whole-genome sequencing as a platform for forward and reverse genetic analysis of Chlamydia. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17:716–725. The first defined collection of Chlamydia mutants that can be used for both forward and reverse genetic analysis of Chlamydia. In this work, 934 EMS and ENU mutagenized Chlamydia strains were generated in a rifampin resistant C. trachomatis strain and clonally isolated to establish an arrayed collection of mutant strains. All EMS/ENU induced mutations present in the genomes of each strain was identified by whole genome sequencing. This defined collection has been used to identify multiple Chlamydia pathogenic factors by forward and reverse genetic approaches.

- 29 *. Sixt BS, Bastidas RJ, Finethy R, Baxter RM, Carpenter VK, Kroemer G, Coers J, Valdivia RH: The Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Protein CpoS Counteracts STING-Mediated Cellular Surveillance and Suicide Programs. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21:113–121. First report linking Chlamydia inclusion membrane proteins and protection against host suicide programs and surveillance pathways.

- 30.Scidmore MA, Hackstadt T: Mammalian 14-3-3beta associates with the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane via its interaction with IncG. Mol. Microbiol 2001, 39:1638–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehlitz A, Banhart S, Mäurer AP, Kaushansky A, Gordus AG, Zielecki J, Macbeath G, Meyer TF: Tarp regulates early Chlamydia-induced host cell survival through interactions with the human adaptor protein SHC1. J. Cell Biol 2010, 190:143–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutter EI, Barger AC, Nair V, Hackstadt T: Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT228 recruits elements of the myosin phosphatase pathway to regulate release mechanisms. Cell Rep. 2013, 3:1921–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mital J, Lutter EI, Barger AC, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T: Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT850 interacts with the dynein light chain DYNLT1 (Tctex1). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2015, 462:165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumoux M, Menny A, Delacour D, Hayward RD: A Chlamydia effector recruits CEP170 to reprogram host microtubule organization. J. Cell Sci 2015, 128:3420–3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35 **. Mirrashidi KM, Elwell CA, Verschueren E, Johnson JR, Frando A, Von Dollen J, Rosenberg O, Gulbahce N, Jang G, Johnson T, et al. : Global Mapping of the Inc-Human Interactome Reveals that Retromer Restricts Chlamydia Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18:109–121. Comprehensive analysis of the interactions of Chlamydia inclusion membrane proteins with host proteins. This work highlights the many potential roles for Chlamydia inclusion membrane proteins during Chlamydia infection of host cells.

- 36.Almeida F, Luís MP, Pereira IS, Pais SV, Mota LJ: The Human Centrosomal Protein CCDC146 Binds Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Protein CT288 and Is Recruited to the Periphery of the Chlamydia-Containing Vacuole. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 2018, 8:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37 **. Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN: Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7:e1002258. Seminal paper describing the first transformation system for a Chlamydia strain. This system allowed for the development of new tools that are now routinely used for molecular genetic analysis of Chlamydia.

- 38.DeMars R, Weinfurter J, Guex E, Lin J, Potucek Y: Lateral gene transfer in vitro in the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol 2007, 189:991–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeMars R, Weinfurter J: Interstrain gene transfer in Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro: mechanism and significance. J. Bacteriol 2008, 190:1605–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40 **. Nguyen BD, Valdivia RH: Virulence determinants in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis revealed by forward genetic approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109:1263–1268. First report of the use of chemical mutagenesis for identifying Chlamydia virulence-associated factors at a genome wide scale by forward genetic approaches. Mutant strains generated by chemical mutagenesis in a rifampin resistant Chlamydia trachomatis strain were used in phenotypic screens. Mutations present in mutants of interest were identified by whole genome sequencing and genetically linked to phenotypic traits by isolating and genotyping recombinant strains generated by horizontal gene transfer events during a backcross to wild type antibiotic resistant strains.

- 41 **. Kari L, Goheen MM, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Virok D, Rajaram K, Endresz V, McClarty G, et al. Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108:7189–7193. In this work, chemical mutagenesis was used to generate pools of Chlamydia mutant strains that were used to identify mutant alleles in genes of interest by reverse genetic approaches.

- 42.Brothwell JA, Muramatsu MK, Toh E, Rockey DD, Putman TE, Barta ML, Hefty PS, Suchland RJ, Nelson DE: Interrogating Genes That Mediate Chlamydia trachomatis Survival in Cell Culture Using Conditional Mutants and Recombination. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198:2131–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43 *. Mueller KE, Wolf K, Fields KA: Gene Deletion by Fluorescence-Reported Allelic Exchange Mutagenesis in Chlamydia trachomatis. MBio 2016, 7:e01817–15. In this work, a system for targeted mutagenesis by homologous recombination is described.

- 44 *. Keb G, Hayman R, Fields KA: Floxed-Cassette Allelic Exchange Mutagenesis Enables Markerless Gene Deletion in Chlamydia trachomatis and Can Reverse Cassette-Induced Polar Effects. J. Bacteriol 2018, 200. This work describes a method for targeted mutagenesis by homologous recombination in which selectable markers are excised from Chlamydia genomes through the use of floxed cassettes. In this fashion marker less gene deletion can be generated, and mutant strains can then be used in subsequent rounds of targeted mutagenesis.

- 45.Falkow S: Molecular Koch’s postulates applied to microbial pathogenicity. Rev. Infect. Dis 1988, 10 Suppl 2:S274–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46 *. Clifton DR, Fields KA, Grieshaber SS, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Mead DJ, Carabeo RA, Hackstadt T: A chlamydial type III translocated protein is tyrosine-phosphorylated at the site of entry and associated with recruitment of actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101:10166–10171. Identification of the first Chlamydia translocated effector involved in invasion of host cells.

- 47.Jewett TJ, Fischer ER, Mead DJ, Hackstadt T: Chlamydial TARP is a bacterial nucleator of actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103:15599–15604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiwani S, Ohr RJ, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T, Alvarado S, Romero A, Jewett TJ: Chlamydia trachomatis Tarp cooperates with the Arp2/3 complex to increase the rate of actin polymerization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2012, 420:816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh S, Ruelke EA, Ferrell JC, Bodero MD, Fields KA, Jewett TJ: Fluorescence-Reported Allelic Exchange Mutagenesis-Mediated Gene Deletion Indicates a Requirement for Chlamydia trachomatis Tarp during In Vivo Infectivity and Reveals a Specific Role for the C Terminus during Cellular Invasion. Infect. Immun 2020, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKuen MJ, Mueller KE, Bae YS, Fields KA: Fluorescence-Reported Allelic Exchange Mutagenesis Reveals a Role for Chlamydia trachomatis TmeA in Invasion That Is Independent of Host AHNAK. Infect. Immun 2017, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keb G, Ferrell J, Scanlon KR, Jewett TJ, Fields KA: Chlamydia trachomatis TmeA Directly Activates N-WASP To Promote Actin Polymerization and Functions Synergistically with TarP during Invasion. MBio 2021, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lane BJ, Mutchler C, Al Khodor S, Grieshaber SS, Carabeo RA: Chlamydial entry involves TARP binding of guanine nucleotide exchange factors. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4:e1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romero MD, Carabeo RA: Distinct roles of Chlamydia trachomatis effectors TarP and TmeA in the regulation of formin and Arp2/3 during entry. J. Cell Sci 2022, doi: 10.1242/jcs.260185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54 *. Chen Y-S, Bastidas RJ, Saka HA, Carpenter VK, Richards KL, Plano GV, Valdivia RH: The Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion chaperone Slc1 engages multiple early effectors, including TepP, a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein required for the recruitment of CrkI-II to nascent inclusions and innate immune signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10:e1003954. One of the first reports in which a Chlamydia translocated effector was validated through the use of genetically complemented mutant strains.

- 55.Carpenter VK, Chen Y-S, Dolat L, Valdivia RH: The Effector TepP Mediates Recruitment and Activation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase on Early Chlamydia trachomatis Vacuoles. mSphere 2017, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolat L, Carpenter VK, Chen Y-S, Suzuki M, Smith EP, Kuddar O, Valdivia RH. Chlamydia repurposes the actin binding protein EPS8 to disassemble epithelial tight junctions and promote infection. In press at Cell Host and Microbe 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dolat L, Valdivia RH: An endometrial organoid model of interactions between Chlamydia and epithelial and immune cells. J. Cell Sci 2021, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saka HA, Thompson JW, Chen Y-S, Kumar Y, Dubois LG, Moseley MA, Valdivia RH: Quantitative proteomics reveals metabolic and pathogenic properties of Chlamydia trachomatis developmental forms. Mol. Microbiol 2011, 82:1185–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gong S, Lei L, Chang X, Belland R, Zhong G: Chlamydia trachomatis secretion of hypothetical protein CT622 into host cell cytoplasm via a secretion pathway that can be inhibited by the type III secretion system inhibitor compound 1. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 2011, 157:1134–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cossé MM, Barta ML, Fisher DJ, Oesterlin LK, Niragire B, Perrinet S, Millot GA, Hefty PS, Subtil A: The Loss of Expression of a Single Type 3 Effector (CT622) Strongly Reduces Chlamydia trachomatis Infectivity and Growth. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 2018, 8:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamaoui D, Cossé MM, Mohan J, Lystad AH, Wollert T, Subtil A: The Chlamydia effector CT622/TaiP targets a nonautophagy related function of ATG16L1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117:26784–26794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62 **. Bugalhão JN, Mota LJ: The multiple functions of the numerous Chlamydia trachomatis secreted proteins: the tip of the iceberg. Microb. Cell 2019, 6:414–449. In depth review of Chlamydia translocated effectors and the multiple roles they play during Chlamydia infection of host cells.

- 63 **. Cortina ME, Bishop RC, DeVasure BA, Coppens I, Derré I: The inclusion membrane protein IncS is critical for initiation of the Chlamydia intracellular developmental cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18:e1010818. One of the first reports detailing the generation of targeted conditional mutants for characterizing essential Chlamydia genes and their products.

- 64.Greene W, Zhong G: Inhibition of host cell cytokinesis by Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J. Infect 2003, 47:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown HM, Knowlton AE, Snavely E, Nguyen BD, Richards TS, Grieshaber SS: Multinucleation during C. trachomatis infections is caused by the contribution of two effector pathways. PLoS ONE 2014, 9:e100763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brown HM, Knowlton AE, Grieshaber SS: Chlamydial infection induces host cytokinesis failure at abscission. Cell. Microbiol 2012, 14:1554–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luís MP, Pereira IS, Bugalhão JN, Simões CN, Mota C, Romão MJ, Mota LJ: The Chlamydia trachomatis IncM Protein Interferes with Host Cell Cytokinesis, Centrosome Positioning, and Golgi Distribution and Contributes to the Stability of the Pathogen-Containing Vacuole. Infect. Immun 2023, 91:e0040522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68 *. Derré I, Swiss R, Agaisse H: The lipid transfer protein CERT interacts with the Chlamydia inclusion protein IncD and participates to ER-Chlamydia inclusion membrane contact sites. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7:e1002092. First description of contact sites at the ER-Chlamydia inclusion interphase.

- 69.Stanhope R, Flora E, Bayne C, Derré I: IncV, a FFAT motif-containing Chlamydia protein, tethers the endoplasmic reticulum to the pathogen-containing vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114:12039–12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elwell CA, Jiang S, Kim JH, Lee A, Wittmann T, Hanada K, Melancon P, Engel JN: Chlamydia trachomatis co-opts GBF1 and CERT to acquire host sphingomyelin for distinct roles during intracellular development. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7:e1002198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ende RJ, Murray RL, D’Spain SK, Coppens I, Derré I: Phosphoregulation accommodates Type III secretion and assembly of a tether of ER-Chlamydia inclusion membrane contact sites. eLife 2022, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen C, Chen D, Sharma J, Cheng W, Zhong Y, Liu K, Jensen J, Shain R, Arulanandam B, Zhong G: The hypothetical protein CT813 is localized in the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane and is immunogenic in women urogenitally infected with C. trachomatis. Infect. Immun 2006, 74:4826–4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adarska P, Wong-Dilworth L, Bottanelli F: ARF gtpases and their ubiquitous role in intracellular trafficking beyond the golgi. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 2021, 9:679046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wesolowski J, Weber MM, Nawrotek A, Dooley CA, Calderon M, St Croix CM, Hackstadt T, Cherfils J, Paumet F: Chlamydia hijacks ARF GTPases to coordinate microtubule posttranslational modifications and Golgi complex positioning. MBio 2017, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A: Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 2002, 420:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar Y, Valdivia RH: Actin and intermediate filaments stabilize the Chlamydia trachomatis vacuole by forming dynamic structural scaffolds. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4:159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77 *. Haines A, Wesolowski J, Ryan NM, Monteiro-Brás T, Paumet F: Cross Talk between ARF1 and RhoA Coordinates the Formation of Cytoskeletal Scaffolds during Chlamydia Infection. MBio 2021, 12:e0239721. This works describes the complex and intricate mechanisms by which the Chlamydia translocated effector InaC regulates host cytoskeleton assembly at the inclusion periphery. The use of genetically engineered Chlamydia strains was central for dissecting the interactions between InaC and host factors controlling cytoskeleton assembly.

- 78.Rzomp KA, Moorhead AR, Scidmore MA: The GTPase Rab4 interacts with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT229. Infect. Immun 2006, 74:5362–5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Faris R, Merling M, Andersen SE, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T, Weber MM: Chlamydia trachomatis CT229 Subverts Rab GTPase-Dependent CCV Trafficking Pathways to Promote Chlamydial Infection. Cell Rep. 2019, 26:3380–3390.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weber MM, Lam JL, Dooley CA, Noriea NF, Hansen BT, Hoyt FH, Carmody AB, Sturdevant GL, Hackstadt T: Absence of Specific Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Proteins Triggers Premature Inclusion Membrane Lysis and Host Cell Death. Cell Rep. 2017, 19:1406–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meier K, Jachmann LH, Pérez L, Kepp O, Valdivia RH, Kroemer G, Sixt BS: The Chlamydia protein CpoS modulates the inclusion microenvironment and restricts the interferon response by acting on Rab35. BioRxiv 2022, doi: 10.1101/2022.02.18.481055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mosallanejad K, Kagan JC: Control of innate immunity by the cGAS-STING pathway. Immunol. Cell Biol 2022, 100:409–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83 *. Walsh SC, Reitano JR, Dickinson MS, Kutsch M, Hernandez D, Barnes AB, Schott BH, Wang L, Ko DC, Kim SY, et al. : The bacterial effector GarD shields Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions from RNF213-mediated ubiquitylation and destruction. Cell Host Microbe 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.08.008. Identification of the inclusion membrane GarD as a Chlamydia effector that protects Chlamydia from cell autonomous IFNγ mediated immunity.

- 84.Haldar AK, Piro AS, Finethy R, Espenschied ST, Brown HE, Giebel AM, Frickel E-M, Nelson DE, Coers J: Chlamydia trachomatis Is Resistant to Inclusion Ubiquitination and Associated Host Defense in Gamma Interferon-Primed Human Epithelial Cells. MBio 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bishop RC, Derré I: The Chlamydia trachomatis Inclusion Membrane Protein CTL0390 Mediates Host Cell Exit via Lysis through STING Activation. Infect. Immun 2022, 90:e0019022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86 *. Yang C, Lei L, Collins JWM, Briones M, Ma L, Sturdevant GL, Su H, Kashyap AK, Dorward D, Bock KW, et al. : Chlamydia evasion of neutrophil host defense results in NLRP3 dependent myeloid-mediated sterile inflammation through the purinergic P2X7 receptor. Nat. Commun 2021, 12:5454. This work describes another function for the GarD C. trachomatis serotype D homolog in promoting cell toxicity in infected neutrophils.

- 87.Giebel AM, Hu S, Rajaram K, Finethy R, Toh E, Brothwell JA, Morrison SG, Suchland RJ, Stein BD, Coers J, et al. : Genetic Screen in Chlamydia muridarum Reveals Role for an Interferon-Induced Host Cell Death Program in Antimicrobial Inclusion Rupture. MBio 2019, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muramatsu MK, Brothwell JA, Stein BD, Putman TE, Rockey DD, Nelson DE: Beyond Tryptophan Synthase: Identification of Genes That Contribute to Chlamydia trachomatis Survival during Gamma Interferon-Induced Persistence and Reactivation. Infect. Immun 2016, 84:2791–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Panzetta ME, Luján AL, Bastidas RJ, Damiani MT, Valdivia RH, Saka HA: Ptr/CTL0175 Is Required for the Efficient Recovery of Chlamydia trachomatis From Stress Induced by Gamma-Interferon. Front. Microbiol 2019, 10:756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhong G: Killing me softly: chlamydial use of proteolysis for evading host defenses. Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen AL, Johnson KA, Lee JK, Sütterlin C, Tan M: CPAF: a Chlamydial protease in search of an authentic substrate. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8:e1002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Snavely EA, Kokes M, Dunn JD, Saka HA, Nguyen BD, Bastidas RJ, McCafferty DG, Valdivia RH: Reassessing the role of the secreted protease CPAF in Chlamydia trachomatis infection through genetic approaches. Pathog. Dis 2014, 71:336–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patton MJ, McCorrister S, Grant C, Westmacott G, Fariss R, Hu P, Zhao K, Blake M, Whitmire B, Yang C, et al. : Chlamydial Protease-Like Activity Factor and Type III Secreted Effectors Cooperate in Inhibition of p65 Nuclear Translocation. MBio 2016, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Muschiol S, Boncompain G, Vromman F, Dehoux P, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B, Subtil A: Identification of a family of effectors secreted by the type III secretion system that are conserved in pathogenic Chlamydiae. Infect. Immun 2011, 79:571–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prusty BK, Chowdhury SR, Gulve N, Rudel T: Peptidase inhibitor 15 (PI15) regulates chlamydial CPAF activity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 2018, 8:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96 **. Rajeeve K, Das S, Prusty BK, Rudel T: Chlamydia trachomatis paralyses neutrophils to evade the host innate immune response. Nat. Microbiol 2018, 3:824–835. First report on extracellular host targets for a Chlamydia secreted effector.

- 97.Tang L, Chen J, Zhou Z, Yu P, Yang Z, Zhong G: Chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF degrades host antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect. 2015, 17:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang Z, Tang L, Zhou Z, Zhong G: Neutralizing antichlamydial activity of complement by Chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18:669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang Z, Tang L, Shao L, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Schenken R, Valdivia R, Zhong G: The Chlamydia-Secreted Protease CPAF Promotes Chlamydial Survival in the Mouse Lower Genital Tract. Infect. Immun 2016, 84:2697–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Olivares-Zavaleta N, Whitmire W, Gardner D, Caldwell HD: Immunization with the attenuated plasmidless Chlamydia trachomatis L2(25667R) strain provides partial protection in a murine model of female genitourinary tract infection. Vaccine 2010, 28:1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kari L, Whitmire WM, Olivares-Zavaleta N, Goheen MM, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, Sturdevant GL, Lu C, Bakios LE, Randall LB, et al. : A live-attenuated chlamydial vaccine protects against trachoma in nonhuman primates. J. Exp. Med 2011, 208:2217–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sigar IM, Schripsema JH, Wang Y, Clarke IN, Cutcliffe LT, Seth-Smith HMB, Thomson NR, Bjartling C, Unemo M, Persson K, et al. : Plasmid deficiency in urogenital isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis reduces infectivity and virulence in a mouse model. Pathog. Dis 2014, 70:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.O’Connell CM, Ingalls RR, Andrews CW, Scurlock AM, Darville T: Plasmid-deficient Chlamydia muridarum fail to induce immune pathology and protect against oviduct disease. J. Immunol 2007, 179:4027–4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ramsey KH, Schripsema JH, Smith BJ, Wang Y, Jham BC, O’Hagan KP, Thomson NR, Murthy AK, Skilton RJ, Chu P, et al. : Plasmid CDS5 influences infectivity and virulence in a mouse model of Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital infection. Infect. Immun 2014, 82:3341–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Y, Huang Y, Yang Z, Sun Y, Gong S, Hou S, Chen C, Li Z, Liu Q, Wu Y, et al. : Plasmid-encoded Pgp3 is a major virulence factor for Chlamydia muridarum to induce hydrosalpinx in mice. Infect. Immun 2014, 82:5327–5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang T, Huo Z, Ma J, He C, Zhong G: The Plasmid-Encoded pGP3 Promotes Chlamydia Evasion of Acidic Barriers in Both Stomach and Vagina. Infect. Immun 2019, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hou S, Dong X, Yang Z, Li Z, Liu Q, Zhong G: Chlamydial plasmid-encoded virulence factor Pgp3 neutralizes the antichlamydial activity of human cathelicidin LL-37. Infect. Immun 2015, 83:4701–4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hou S, Sun X, Dong X, Lin H, Tang L, Xue M, Zhong G: Chlamydial plasmid-encoded virulence factor Pgp3 interacts with human cathelicidin peptide LL-37 to modulate immune response. Microbes Infect.2019, 21:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Haines A, Wesolowski J, Paumet F: Chlamydia trachomatis Subverts Alpha-Actinins To Stabilize Its Inclusion. Microbiol. Spectr 2023, 11:e0261422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]