Abstract

Various new psychoactive substances, such as cathinone and its analogs, possess similar chemical structures. Accurate identification of structurally similar drugs of abuse is important in forensic drug analysis. Chromatographic differentiation is a powerful analytical technique for this purpose. In this study, we applied supercritical fluid chromatography to differentiate ring‐substituted regioisomers of six synthetic cathinone analogs (fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone, fluoropentedrone, and fluorooctedrone). The examined cathinone analogs were weakly retained on the stationary phase (possessing diol functional group) and eluted quickly. We optimized the conditions to retain the examined cathinone analogs to achieve sufficient separation, and found that the types of functional groups on the stationary phase greatly affected the retention and separation. Systematic examination of the chromatographic conditions showed that the two stationary phases possessing anthracene and pentafluorobenzyl groups had good separation capabilities for the examined 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐regioisomers of six cathinone analogs, which had different skeletal structures. Interestingly, the two stationary phases showed different selectivities, and alteration of the elution order was observed. The developed method was validated and its discrimination ability was investigated by measuring mass spectra and absorption spectra. Supercritical fluid chromatography‐ultraviolet absorption spectroscopy/mass spectrometry is a powerful analytical technique for differentiation of ring‐substituted cathinone analogs.

Keywords: cathinone, mass spectrometry, regioisomer, supercritical fluid chromatography

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

To date, multiple new psychoactive substances (NPS) have been synthesized and abused. NPS are prevalent worldwide, and new drugs are continuously synthesized and sold on the illegal market. 1 , 2 , 3 Emerging NPS frequently have similar chemical structures to existing drugs. Psychological effects of these analogs can vary from the original drugs. 4 , 5 Legislation to control emerging NPS is under continual development worldwide.

One of the major categories of NPS is synthetic cathinones. 6 Original cathinone is an alkaloid contained in a plant khat, possessing the stimulant effect. To elude the drug controlling legislations, various synthetic cathinones are synthesized by modifying the chemical structure of cathinone. Namely, adding substituents on the benzene ring, elongating the carbon chain length, and changing the structure of amine group. For example, α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, which is one of the most prevailing synthetic cathinone, has an elongated C5 carbon chain and a modified pyrrolidine amine group. To control these structurally various compounds, in Japan the generic scheduling is introduced. But presently, the situation of controlling synthetic cathinone is different from country to country.

The accurate identification of emerging NPS is important in forensic drug analysis. For structurally similar drugs such as positional isomers, the drug potency depends on the positions of substituents. 7 In some legislation, particular positional isomers are regulated by drug control law, whereas the others are not. Consequently, differentiation of structurally similar drugs is required, which can be analytically challenging. Spectroscopic techniques such as infrared absorption spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy have high discrimination capability to distinguish the structurally similar compounds. 8 , 9 However, these techniques generally require that the samples are single ingredient and highly pure. Compared with this, chromatographic separation is a powerful and straightforward way to differentiate structural analogs because it enables performing separation and qualitative analysis of the sample components simultaneously. Gas chromatography (GC) and liquid chromatography (LC) are indispensable analytical techniques for drug analysis. Various structurally similar drugs, such as amphetamine‐type stimulants, narcotics, legal medicines, and also NPS including synthetic cathinones, can be successfully analyzed by GC and LC. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Subtle changes in chemical structures, such as elongation of the carbon skeleton or substitution of functional groups, can be identified using these techniques.

Among structurally similar analogs, ring‐substituted regioisomers are often the most challenging compounds to separate. These drugs have one or more substituents linking to their benzene rings of the original drugs, and only differ in the positions of the substituents. There have been reports on the separation of some drugs, such as halogenated amphetamine and methamphetamine, by GC and LC. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Although these techniques have high separation capabilities, it is still challenging to differentiate ring‐substituted regioisomers by GC and LC because of their similar physicochemical properties.

Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) is another potential method for chromatographic separation. Generally, SFC uses supercritical (or subcritical) carbon dioxide (CO2) as the main component of the mobile phase. The low viscosity and high diffusivity of supercritical CO2 allow for rapid and highly efficient analysis. The selectivity of the elution differs from that in LC, 20 which means the compounds that cannot be separated by GC and LC could be separated by SFC. Recent development of instruments enables repeatable and reliable analysis. Because of these advantages, SFC has been increasingly applied to pharmaceutical and drug analyses, 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 although the application to the forensic drug analysis is presently not usual. We previously showed that ring‐substituted regioisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine analogs could be separated by SFC, and the analysis was quicker than previously reported methods using GC and LC. 22 Our results support the use of SFC as a powerful analytical technique in the field of forensic drug analysis.

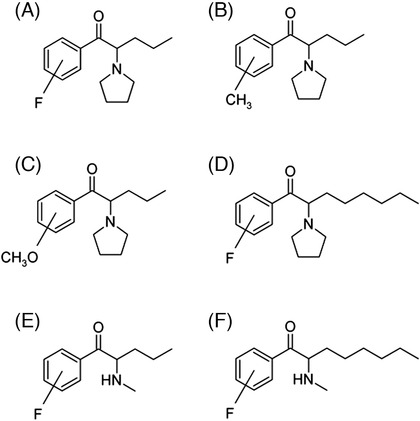

In the present study, we aimed to extend the range of application of regioisomeric separation by SFC to 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐position ring‐substituted regioisomers of cathinone analogs. The selected cathinone analogs were fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone (FPVP), methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone (MePVP), methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone (MeOPVP), fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone (FPOP), fluoropentedrone (FPR), and fluorooctedrone (FOR) (Figure 1). These compounds possess different types of substituents (electron‐donating methyl and methoxy groups, electron‐withdrawing fluoro group, side chain structure of pyrrolidine and methylamine, and different carbon chain length). Thus, it was expected that some insight into the interaction between the column stationary phase and the compounds would be obtained during the method optimization, which would contribute to understanding the retention behavior of SFC. The method was optimized as in our previous study, 22 and the optimized method was validated. Its ability to identify compounds with various substituent types and positions was evaluated, and the structure‐retention relationships were discussed.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structures of the target molecules of interest. A, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. B, Methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. C, Methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. D, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone. E, Fluoropentedrone. F, Fluorooctedrone.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1. Chemicals

LC/mass spectrometry (MS)‐grade methanol (MeOH), 2‐propanol (2PrOH) and 1 M ammonium formate (AF) aqueous solution, and analytical grade 28% aqueous ammonium (NH3) were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). Ultrapure water was produced using a Milli‐Q Integral 5 system (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The examined cathinone analogs were synthesized in the laboratory using established methods with some modifications, 25 , 26 , 27 and purified sufficiently for instrumental analysis. CO2 of >99.5% purity was purchased from Jyotou Gas (Tokyo, Japan).

Co‐solvents and the make‐up solvent used for SFC were prepared in our laboratory. Organic solvents (MeOH or 2PrOH) and additives (NH3 or AF) were mixed and filtered through a Millicup HV 0.45‐µm polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Merck) before use.

2.2. Sample preparation

The examined cathinone analogs were kept as 100 µg/mL solutions in 2PrOH. Purities were checked by general analytical techniques such as GC/MS. 28 For method development and validation, the stock solutions were mixed or sequentially diluted to 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000, and 5000 ng/mL with 2PrOH. An internal standard (4‐fluoro‐N‐ethylhexedrone for FPVP, FPOP, FPR, and FOR or 4‐methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinohexanophenone for MePVP and MeOPVP) was added to each validation sample for normalizing the intensity fluctuation of the mass spectrometer. Note that the internal standard compounds were also synthesized in the laboratory, and selected based on the retention time proximity. The mixed or diluted solutions were filtered through 0.2‐µm polytetrafluoroethylene filters (Ultrafree MC, Merck). Filtered solutions were directly injected into the instruments.

2.3. Instruments

SFC was performed using an ultra‐performance convergence chromatography (UPC 2 ) system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Various columns were used during method development. Torus 2‐PIC, Torus Diol, Torus 1‐AA, Torus DEA, and Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl columns (100 × 3 mm i.d., 1.7 µm particle size) were purchased from Waters. COSMOSIL πMAX and COSMOSIL PBr columns (150 × 2 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size) were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). DCpak P4VP and DCpak PBT columns (150 × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size) were purchased from Daicel (Osaka, Japan). An Inertsil ODS‐EP column was purchased from GL science (Tokyo, Japan). The co‐solvents were MeOH and 2PrOH containing AF (10 or 20 mM) or 0.28% NH3. The make‐up solvent used for enhancing the ionization efficiency in MS was MeOH containing 20 mM AF. Two different sets of conditions were evaluated for method optimization. The first of these used the Torus 1‐AA column, a temperature of 60°C, and isocratic elution with 97:3 CO2:co‐solvent (MeOH containing 20 mM AF). The second set of conditions used a Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column, temperature of 40°C, and gradient elution with CO2:co‐solvent (MeOH containing 20 mM AF). In the gradient elution, the CO2:co‐solvent was changed from 97:3 (0‐5.5 min) to 82:18 (5.5‐6 min), held at 82:18 until 7.5 min, changed to 97:3 (7.5‐8 min), and held at 97:3 until 10 min. The mobile phase flow rate was 1 mL/min, the sample injection volume was 1 µL, and the back pressure was 10.3 MPa. Signal detection was performed using both ultraviolet (UV) absorption with a photodiode array detector included in the UPC 2 system and MS using a quadrupole time‐of‐flight mass spectrometer (SYNAPT high‐definition mass spectrometry system, Waters). Ionization was performed in positive electrospray ionization mode. The MS conditions were a capillary voltage of 4 kV, cone voltage of 20 V, source temperature of 120°C, desolvation temperature of 500°C, and trap cell and transfer cell collision energy of 10 or 15 eV. The precursor and extracted ions used for method validation are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. The chromatograph and the mass spectrometer were directly interfaced using a PEEKsil tube (50 µm inner diameter).

TABLE 1.

Method validation under the optimized conditions with a Torus 1‐AA column

| Torus 1‐AA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regioisomer | Precursor ion (m/z) | Extracted ion (m/z) | LOD (pg) | Linear range (ng/mL) | R 2 | RSD of RT (n = 4) (%) | Resolution | |

| FPVP | 3 | 250 | 109 | 1 × 10 | 5‐500 | .999 | 0.24 | N/A |

| 4 | 4 | .998 | 0.28 | 2.7 | ||||

| 2 | 1 × 10 | .999 | 0.30 | 1.0 | ||||

| MePVP | 2 | 246 | 105 | 5 × 10 | 50‐1000 | >.999 | 8.0 × 10−3 | N/A |

| 3 | 1 | 1‐500 | 0.082 | 0.85 | ||||

| 4 | 1 | 1‐100 | 8.0 × 10−3 | 5.4 | ||||

| MeOPVP | 3 | 262 | 121 | 5 | 5‐1000 | >.999 | 0.60 | N/A |

| 4 | 5 | 1.1 | 16 | |||||

| 2 | 2 × 10 | 1.0 | 6.9 | |||||

| FPOP | 3 | 292 | 109 | 5 | 5‐1000 | >.999 | 0.11 | N/A |

| 4 | 5 | 0.11 | 3.2 | |||||

| 2 | 5 | 0.074 | 1.3 | |||||

| EPR | 2 | 210 | 192 | 6 | 1‐1000 | >.999 | 0.29 | N/A |

| 3 | 3 | 0.29 | 1.0 | |||||

| 4 | 1 | 0.30 | 2.4 | |||||

| FOR | 2 | 252 | 234 | 2 | 1‐500 | >.999 | 0.57 | N/A |

| 3 | 1 | 0.51 | 1.0 | |||||

| 4 | 1 | 0.49 | 2.5 | |||||

Abbreviations: FOR, fluorooctedrone; FPOP, fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone; FPR, fluoropentedrone; FPVP, fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; LOD, limit of detection; MeOPVP, methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; MePVP, methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; R 2, coefficient of determination; RSD, relative standard deviation; RT, retention time.

TABLE 2.

Method validation under the optimized conditions with a Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column

| Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regioisomer | Precursor ion (m/z) | Extracted ion (m/z) | LOD (pg) | Linear range (ng/mL) | R 2 | RSD of RT (n = 4) (%) | Resolution | |

| FPVP | 3 | 250 | 109 | 6 | 5‐100 | >.999 | 0.37 | N/A |

| 4 | 5 | >.999 | 0.36 | 5.8 | ||||

| 2 | 8 | .998 | 0.32 | 5.2 | ||||

| MePVP | 2 | 246 | 105 | 1 × 10 | 1‐500 | >.999 | 0.21 | N/A |

| 3 | 2 | 0.14 | 1.3 | |||||

| 4 | 2 | 0.20 | 6.1 | |||||

| MeOPVP | 3 | 262 | 121 | 3 | 1‐500 | >.999 | 0.10 | N/A |

| 4 | 1 | 1‐100 | 0.025 | 18 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 1‐500 | 0.024 | 10 | ||||

| FPOP | 3 | 292 | 109 | 1 | 1‐100 | .998 | 1.5 | N/A |

| 4 | 1 | .996 | 0.45 | 4.1 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | >.999 | 0.19 | 5.0 | ||||

| EPR | 3 | 210 | 192 | 2 | 1‐100 | >.999 | 0.31 | N/A |

| 4 | 3 | .997 | 0.27 | 3.3 | ||||

| 2 | 3 | .991 | 0.26 | 1.5 | ||||

| FOR | 3 | 252 | 234 | 1 | 1‐100 | >.999 | 0.26 | N/A |

| 4 | 1 | 0.22 | 2.1 | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 0.33 | 1.8 | |||||

Abbreviations: FOR, fluorooctedrone; FPOP, fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone; FPR, fluoropentedrone; FPVP, fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; LOD, limit of detection; MeOPVP, methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; MePVP, methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone; R 2, coefficient of determination; RSD, relative standard deviation; RT, retention time.

2.4. Validation experiments

Method validation was performed by measuring the mixed and sequentially diluted solutions under the optimized conditions described above. Each concentration sample was repeatedly measured for four times. The precursor and extracted ions used for depicting extracted ion chromatograms are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The limit of detection (LOD) was basically estimated as the amount of compound giving a peak height of three times the standard deviation of the baseline noise. If the calculated LOD was lower than the calibration range of the validation experiments, the lowest value of the calibration range was assigned. The linear range was determined as the concentration not showing saturation behavior. The resolution between each regioisomer was calculated as follows:

where Rt is the retention time and FWHM is the full width at half maximum. Subscripts indicate the regioisomers.

2.5. Data analysis

The instruments were controlled by Masslynx 4.1 software (Waters). Calibration of parameters required for validating the method was performed by Igor Pro 8 software (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Method optimization

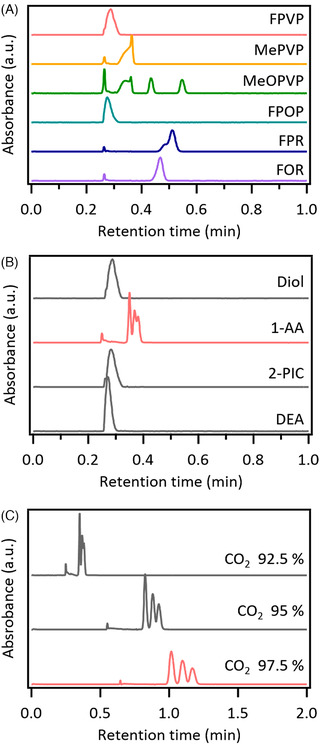

In a previous study, we differentiated among ring‐substituted regioisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine analogs using an UPC 2 system. 22 In the present study, the same experimental conditions (Torus Diol column and the co‐solvent of methanol containing 0.28% of NH3) were first applied to the cathinone analogs. Chromatograms were obtained using a photodiode array detector at 240 nm (Figure 2A). Although these conditions were suitable for the retention and separation of ring‐substituted methamphetamine analogs, the examined regioisomers of cathinones analogs were poorly retained on the stationary phase and unresolved, with the exception of MeOPVP (Figure 1C). Therefore, we investigated optimization of the chromatographic conditions for stronger retention of the cathinone analogs.

FIGURE 2.

Chromatograms obtained during method optimization. A, Chromatograms of the six cathinone analogs examined using previously reported conditions with a Torus Diol column and co‐solvent of methanol containing 0.28% ammonium. 22 B, Chromatograms of fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone (FPVP) on four different Torus columns. C, Chromatograms of FPVP on the Torus 1‐AA column with different mobile phase compositions

The most straightforward way to improve retention of samples in SFC is to optimize the stationary phase and mobile phase composition. First, we changed the type of the stationary phase and investigated four different Torus columns. These columns have been developed specifically for SFC and their stationary phases possess different chemical properties. A mixture of 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐position ring‐substituted regioisomers of FPVP (Figure 1A) was analyzed and the chromatograms are shown in Figure 2B. The Torus 1‐AA column, which contains anthracene derivatives, showed stronger retention than the other columns. Consequently, further optimization was performed using the Torus 1‐AA column. To do this, the mobile phase composition was changed and the retention behavior was investigated. In SFC, increasing the proportion of CO2 generally results in a decrease in the elution strength. The chromatograms of FPVP obtained with three different mobile phase compositions are shown in Figure 2C. Increasing the proportion of CO2 resulted in longer retention times and better resolution between the regioisomers.

On the basis of the above examinations and further investigations, the optimized experimental conditions, described in the experimental section, were established and applied to cathinone analogs (Figure 3A). Although separation of MePVP (Figure 1B) was incomplete, the five other analogs were separated. MeOPVP (Figure 1C) showed stronger retention than the other analogs and a long analysis time was required. Because the resolution of each peak was high, reducing the retention time by increasing the co‐solvent proportion or the flow rate was expected to be effective for MeOPVP.

FIGURE 3.

Chromatograms of six cathinone analogs obtained under the optimized conditions with (A) a Torus 1‐AA column, (B) a Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column, and (C) a COSMOSIL PBr column. The numbers in the chromatograms indicate the positions of substituents on the benzene ring. Because the sufficient separation was not obtained for COSMOSIL PBr, the elution order of this column was not investigated

In the evaluation of the Torus columns, only Torus 1‐AA showed sufficient retention and peak resolution (Figure 2B). Taking into consideration the chemical structures of the columns’ stationary phases, this indicates that the dispersive interaction given by the large aromatic group on the stationary phase of Torus 1‐AA column might be important for peak separation. Consequently, we attempted to separate the examined cathinone analogs using other types of columns with strong dispersive interaction. The columns used were a Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column with pentafluorophenyl groups, a COSMOSIL πMAX column with pyrenylethyl groups, and a COSMOSIL PBr column with pentabromophenyl groups. Chromatograms obtained using the Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column (Figure 3B) showed that all examined cathinone analogs, including MePVP, were successfully separated. A gradient elution was applied because the MeOPVPs (Figure 1C) eluted quite slowly under the isocratic elution. By contrast, πMAX and PBr columns showed incomplete separation. For the πMAX column, all cathinone analogs were not retained and they eluted at the solvent front (data not shown). For the PBr column, regioisomeric separation was partly observed but it was inferior to that of the Fluoro‐Phenyl column (Figure 3C). Other types of columns (DCpak PBT, DCpak P4VT, and Inertsil ODS‐EP) were evaluated but none could achieve complete separation between ring‐substituted regioisomers of each cathinone analog. The Inertsil ODS‐EP column in particular had weak retention (data not shown).

3.2. Discrimination ability of the developed method

Both mass spectra and UV absorption spectra were measured and compared to evaluate the ability to differentiate each regioisomer. Mass spectra of the examined compounds are shown in Figure 4. The speculated fragmentations are described in Figure S1. Despite the different substituents and side chain structures, the examined cathinone analogs showed similar fragmentation patterns, which were consistent with those in previous reports. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 All examined cathinone analogs (Figure 1) showed tropylium ion‐like fragment ions (m/z 109 for FPVP, FPOP, FPR, and FOR; m/z 105 for MePVP; and m/z 121 for MeOPVP). These fragments possessed substituted functional groups and could be used for characterization of the types of substituents. The analogs with pyrrolidinyl groups (FPVP, MePVP, MeOPVP, and FPOP; Figure 1A‐D) showed characteristic fragments at m/z 70 and [M + H]+ −30. The former ion corresponds to the pyrrolidine ring. Though it was difficult to assign the ion at m/z [M + H]+ −30, we speculated this fragment was related to the pyrrolidinyl group because this fragment was not found in the spectra for FPR and FOR (Figures 1E and 1F). By contrast, analogs with methylamino groups (FPR and FOR; Figures 1E and 1F) showed characteristic fragments with m/z [M + H]+ −18, which we speculated was for dehydrated ions of the protonated molecules. Because this fragmentation was not found for the analogs with pyrrolidinyl groups, the methylamino group must contribute to dehydration and this fragment could be used for characterization. Differentiation of the 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐position regioisomers was difficult because the fragment peaks were almost the same for all the regioisomers. Although some peaks showed different ratios for the intensities, this difference was small and it was difficult to identify the position of the substituent using the mass spectra.

FIGURE 4.

Mass spectra of the target molecules of interest. All spectra are ordered as 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐positional isomers from the top to the bottom. A, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. B, Methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. C, Methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. D, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone. E, Fluoropentedrone. F, Fluorooctedrone.

UV absorption spectra of the examined compounds are shown in Figure 5. In the studied wavelength region, two absorption bands originating from the aromatic benzene ring were found. Generally, these absorptions correspond to symmetrically forbidden electronic transitions and have small absorption coefficients. Substituents on the benzene ring can alter absorption peaks and intensities. The degree of this alteration depends on the types and positions of the substituents. In the present case, it is difficult to differentiate substituents on the benzene ring using the UV spectra, although the methoxy group appears to be different from the others. By contrast, differentiation of the 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐position regioisomers was achievable because each UV spectrum sensitively reflected any difference in the substituent's position on the benzene ring. Combination of MS and UV absorption spectroscopy is a powerful discrimination method for ring‐substituted regioisomeric cathinone analogs.

FIGURE 5.

Ultraviolet‐visible absorption spectra of the target molecules of interest. All spectra are ordered as 2‐, 3‐, and 4‐positional isomers from the top to the bottom. A, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. B, Methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. C, Methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone. D, Fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone. E, Fluoropentedrone. F, Fluorooctedrone. Dashed lines indicate the peak positions of each spectrum

3.3. Method validation

The results of method validation are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The obtained LODs were equivalent to those of ring‐substituted methamphetamines in the previous study (1‐60 pg, on column) 22 and those of literatures performing synthetic cathinone analyses. 32 , 33 This indicates that the presence of a carbonyl group in the cathinone skeleton does not affect the ionization efficiency for SFC/MS. The obtained resolutions (Tables 1 and 2) indicated that most of the isomers were baseline‐separated (>1.5), particularly using the Fluoro‐Phenyl column. The retention time standard deviation was calculated from the retention times of four injections. The interday relative standard deviations of the retention time were 0.01% for 1‐AA and 0.3% for Fluoro‐Phenyl, calculated from the retention time of the internal standard.

3.4. Consideration of the elution behavior

The differences in the separation capabilities between PBr and Fluoro‐Phenyl columns are interesting because both stationary phases are functionalized by a halogenated benzene ring and are likely to possess similar chemical properties. Although the dimensions of the COSMOSIL PBr (150 × 2 mm i.d., 5 µm particle size) and Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl (100 × 3 mm i.d., 1.7 µm particle size) columns used in this study were different, the observed difference of the resolution of the individual ring‐substituted regioisomers of each analog was considered to be greater than that could be explained by the difference in the column dimensions alone. Consequently, we considered how the stationary phase in the column could play an important role. Another factor affecting the separation ability is the surface state of the stationary phase. For the PBr column, the functional group carrier is end‐capped silica. By contrast, the Fluoro‐Phenyl column has a carrier with small charges on its surface, according to the manufacturer. This difference of the surface charge state might affect the ability to separate regioisomers. The poor retention ability of the πMAX column indicated that the dispersive interaction (or π‐electron interaction) alone was insufficient to retain the examined synthetic cathinones.

The difference in elution behaviors between the 1‐AA and Fluoro‐Phenyl columns (Figure 3A and 3B) is also interesting. These two stationary phases resolved most regioisomers of the examined cathinone analogs but their selectivities and elution behaviors are different, even though they are structurally similar as they both contain aromatic functional groups. The chromatograms of FPR (Figure 1E) and FOR (Figure 1F) obtained using the 1‐AA and Fluoro‐Phenyl columns are shown in Figure 6. On the 1‐AA column (Figure 6A), FPR and FOR were well separated, but on the Fluoro‐Phenyl (Figure 6B) column these two compounds eluted almost at the same time. The structural difference between FPR and FOR is the length of the alkyl chain. Therefore, these results indicate that the stationary phase of the Fluoro‐Phenyl column mainly recognizes (or interacts with) the benzene ring of the compound and has low sensitivity toward alkyl chain length. By contrast, the stationary phase of the 1‐AA column can recognize differences in both the benzene ring and alkyl chain length. Notably, the elution order of the regioisomers also differed between the 1‐AA and Fluoro‐Phenyl columns (Figure 6; Tables 1 and 2). These results suggest the 1‐AA and Fluoro‐Phenyl columns have different mechanisms of retention.

FIGURE 6.

Enlarged chromatograms of fluoropentedrone (FPR) and fluorooctedrone (FOR) under the optimized conditions with (A) a Torus 1‐AA column and (B) a Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column. Numbers shown in the chromatograms indicate the positions of substituents on the benzene ring

In comparison with the results of our previous study, 22 the elution order (Tables 1 and 2) in this study was different. We previously reported that the elution order of ring‐substituted regioisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine depended on the properties of the substituents. Namely, electron‐donating methyl and methoxy groups (3 > 4 > 2 or 3 > 2 > 4) and electron‐withdrawing fluoro, chloro, and bromo groups (2 > 3 > 4) showed different orders (note that the numbers indicate the positions of substituents on the benzene ring). However, the examined cathinone analogs did not follow this order. Because cathinones contain electron‐withdrawing carbonyl groups adjacent to the benzene ring, we predicted that the order of 2 > 3 > 4 would be basically observed. However, in reality, most of the compounds showed an elution order of 3 > 4 > 2 even with an electron‐withdrawing fluoro group substituent. This result indicates that the elution order of regioisomers cannot be predicted simply from the types of substituents on the benzene ring, and further studies are required to clarify the mechanism affecting the elution order. For determining the structure‐retention relationship of chromatography, the linear solvation energy relationship is useful. 34 , 35 , 36 This method can predict the retention time of the compound and the physicochemical properties contributing to the interaction between the column stationary phase and the molecules, through measuring a great number of standard compounds. Though such a large‐scale research is beyond the scope this study, the continuous measurements of various illegal drugs of abuse with different physicochemical property will give a clue to understanding the retention behavior of drug molecules in SFC.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we aimed to differentiate among ring‐substituted regioisomers of cathinone analogs. Separation of ring‐substituted regioisomers of six synthetic cathinone analogs was achieved under two sets of optimized conditions using columns with different stationary phases (Torus 1‐AA and Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl columns). Except for MeOPVP, the separation was rapid and completed within 10 min. The method validation results showed sufficient stability of the retention time, linearity, and LOD, which was comparable with the previously reported LC‐MS/MS method for seized samples. The combined detection of UV and MS was powerful for identifying substituents and their positions on the benzene ring. These facts indicate that the developed method will contribute to rapid qualitative analysis of the seized NPS. Although the further examinations such as the sample pretreatment or matrix effect evaluations are necessary, the developed methods might be applicable to the biological samples due to their high sensitivity. The stationary phases of both columns contain aromatic functional groups, and the dispersive effect of the aromatic groups apparently plays an important role in separation of the examined cathinone analogs. The Torus 1‐AA column and Viridis CSH Fluoro‐Phenyl column had different selectivities, which affected the order of elution because the recognition sites on the molecules in the stationary phase were different. This is useful for drug analysis purposes because the identification accuracy will increase when the chromatographic results obtained under different conditions with different selectivities coincide.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

Supporting information

Figure S‐1 Speculated fragmentation of examined cathinone analogs. (a) fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (b) methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (c) methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (d) fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone, (e) fluoropentedrone, and (f) fluorooctedrone. All spectra are 3‐positional isomers of each analog.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant‐in Aid for Encouragement of Scientists (Grant Number JP17H00299). We thank Gabrielle David, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Segawa H, Kusakabe K, Ishii A, et al. Differentiation of ring‐substituted regioisomers of cathinone analogs by supercritical fluid chromatography. Anal Sci Adv. 2020;1:22–33. 10.1002/ansa.202000027

REFERENCES

- 1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . Current NPS Threats. Vol. 1. Vienna, Austria: UNODC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . World Drug Report 2018. Vienna, Austria: UNODC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brandt SD, Kavanagh PV. Addressing the challenges in forensic drug chemistry. Drug Test Anal. 2017;9(3):342‐346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelly JP. Cathinone derivatives: a review of their chemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Drug Test Anal. 2011;3(7‐8):439‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prosser JM, Nelson LS. The toxicology of bath salts: a review of synthetic cathinones. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(1):33‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . Synthetic cathinones. https://www.unodc.org/LSS/SubstanceGroup/Details/67b1ba69-1253-4ae9-bd93-fed1ae8e6802. Accessed March 6, 2020.

- 7. Longworth M, Banister SD, Mack JBC, Glass M, Connor M, Kassiou M. The 2‐alkyl‐2H‐indazole regioisomers of synthetic cannabinoids AB‐CHMINACA, AB‐FUBINACA, AB‐PINACA, and 5F‐AB‐PINACA are possible manufacturing impurities with cannabimimetic activities. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(2):286‐303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brandt SD, Daley PF, Cozzi NV. Analytical characterization of three trifluoromethyl‐substituted methcathinone isomers. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(6):525‐529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christie R, Horan E, Fox J, et al. Discrimination of cathinone regioisomers, sold as ‘legal highs’, by Raman spectroscopy. Drug Test Anal. 2014;6(7‐8):651‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pettersson Bergstrand M, Helander A, Beck O. Development and application of a multi‐component LC–MS/MS method for determination of designer benzodiazepines in urine. J Chromatogr B. 2016;1035:104‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uchiyama N, Matsuda S, Kawamura M, et al. Characterization of four new designer drugs, 5‐chloro‐NNEI, NNEI indazole analog, α‐PHPP and α‐POP, with 11 newly distributed designer drugs in illegal products. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;243:1‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kankaanpää A, Gunnar T, Ariniemi K, Lillsunde P, Mykkänen S, Seppälä T. Single‐step procedure for gas chromatography–mass spectrometry screening and quantitative determination of amphetamine‐type stimulants and related drugs in blood, serum, oral fluid and urine samples. J Chromatogr B. 2004;810(1):57‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Negishi S, Nakazono Y, Iwata YT, et al. Differentiation of regioisomeric chloroamphetamine analogs using gas chromatography–chemical ionization‐tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):338‐347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elbardisy Hadil M, Foster CW, Cumba L, et al. Analytical determination of heroin, fentanyl and fentalogues using high‐performance liquid chromatography with diode array and amperometric detection. Anal. Methods. 2019;11(8):1053‐1063. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aalberg L, DeRuiter J, Noggle FT, Sippola E, Clark CR. Chromatographic and mass spectral methods of identification for the side‐chain and ring regioisomers of methylenedioxymethamphetamine. J Chromatogr Sci. 2000;38(8):329‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li L, Lurie IS. Regioisomeric and enantiomeric analyses of 24 designer cathinones and phenethylamines using ultra high performance liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis with added cyclodextrins. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;254:148‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakazono Y, Tsujikawa K, Kuwayama K, et al. Differentiation of regioisomeric fluoroamphetamine analogs by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2013;31(2):241‐250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martens J, Koppen V, Berden G, Cuyckens F, Oomens J. Combined liquid chromatography‐infrared ion spectroscopy for identification of regioisomeric drug metabolites. Anal Chem. 2017;89(8):4359‐4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inoue H, Negishi S, Nakazono Y, et al. Differentiation of ring‐substituted bromoamphetamine analogs by gas chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):125‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gourmel C, Grand‐Guillaume Perrenoud A, Waller L, et al. Evaluation and comparison of various separation techniques for the analysis of closely‐related compounds of pharmaceutical interest. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1282:172‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segawa H, Iwata YT, Yamamuro T, et al. Simultaneous chiral impurity analysis of methamphetamine and its precursors by supercritical fluid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2019;37(1):145‐153. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Segawa HT, Iwata Y, Yamamuro T, et al. Differentiation of ring‐substituted regioisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine by supercritical fluid chromatography. Drug Test Anal. 2017;9(3):389‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beucher L, Dervilly‐Pinel G, Cesbron N, et al. Specific characterization of non‐steroidal selective androgen peceptor modulators using supercritical fluid chromatography coupled to ion‐mobility mass spectrometry: application to the detection of enobosarm in bovine urine. Drug Test Anal. 2017;9(2):179‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. González‐Mariño I, Thomas KV, Reid MJ. Determination of cannabinoid and synthetic cannabinoid metabolites in wastewater by liquid–liquid extraction and ultra‐high performance supercritical fluid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Test Anal. 2018;10(1):222‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shima N, Katagi M, Kamata H, et al. Metabolism of the newly encountered designer drug α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone in humans: identification and quantitation of urinary metabolites. Forensic Toxicol. 2014;32(1):59‐67. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee JC, Bae YH, Chang S‐K. Efficient a‐halogenation of carbonyl compounds by N‐bromosuccinimide and N‐chlorosuccinimde. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2003;24(4):407‐408. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kajigaeshi S, Kakinami T. Benzyltrimethylammonium tribromide. J Synth Org Chem Jpn. 1988;46(10):986‐989. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kusakabe K, Segawa H, Iwata YT, Ishii A, Kobayashi K, Kato N. Study on identification of regioisomeric cathinone derivatives. 25th Annual Meeting of Japanese Association of Forensic Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 2019.

- 29. Fabregat‐Safont D, Sancho JV, Hernández F, Ibáñez M. Rapid tentative identification of synthetic cathinones in seized products taking advantage of the full capabilities of triple quadrupole analyzer. Forensic Toxicol. 2019;37(1):34‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellefsen KN, Wohlfarth A, Swortwood MJ, Diao X, Concheiro M, Huestis MA. 4‐Methoxy‐α‐PVP: in silico prediction, metabolic stability, and metabolite identification by human hepatocyte incubation and high‐resolution mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):61‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsuta S, Shima N, Kamata H, et al. Metabolism of the designer drug α‐pyrrolidinobutiophenone (α‐PBP) in humans: identification and quantification of the phase I metabolites in urine. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;249:181‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jankovics P, Váradi A, Tölgyesi L, Lohner S, Németh‐Palotás J, Kőszegi‐Szalai H. Identification and characterization of the new designer drug 4′‐methylethcathinone (4‐MEC) and elaboration of a novel liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) screening method for seven different methcathinone analogs. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;210(1):213‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Synthetic Cathinones in Seized Materials. Vienna, Austria: UNODC; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abraham MH, Ibrahim A, Zissimos AM. Determination of sets of solute descriptors from chromatographic measurements. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1037(1‐2):29‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bui H, Masquelin T, Perun T, Castle T, Dage J, Kuo M‐S. Investigation of retention behavior of drug molecules in supercritical fluid chromatography using linear solvation energy relationships. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1206(2):186‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. West C, Lemasson E, Bertin S, Hennig P, Lesellier E. An improved classification of stationary phases for ultra‐high performance supercritical fluid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2016;1440(Supplement C):212‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S‐1 Speculated fragmentation of examined cathinone analogs. (a) fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (b) methyl‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (c) methoxy‐α‐pyrrolidinovalerophenone, (d) fluoro‐α‐pyrrolidinooctanophenone, (e) fluoropentedrone, and (f) fluorooctedrone. All spectra are 3‐positional isomers of each analog.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.