Abstract

Background

Legislation in the European Union (EU) and the USA promoting the development of paediatric medicines has contributed to new treatments for children. This study explores how such legislation responds to paediatric health needs in different country settings and globally, and whether it should be considered for wider implementation.

Methods

We searched EU and US regulatory databases for medicines with approved indications resulting from completed paediatric development between 2007 and 2018. Of 195 medicines identified, 187 could be systematically mapped to the burden of the target disease for six study countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Kenya, Russia, South Africa) and globally, using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). All medicines were also screened for inclusion on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) and the EML for children under 13 years (EMLc).

Results

The studied medicines were disproportionately focused on non-communicable diseases, which represented 68% of medicines and 21% of global paediatric DALYs. On the other hand, we found 28% of medicines for communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional disorders, representing 73% of global paediatric DALYs. Neonatal disorders and malaria were mapped with two medicines, tuberculosis and neglected tropical diseases with none. The gap between medicines and paediatric DALYs was greater in countries with lower income. Still, 34% of medicines are included in the EMLc and 48% in the EML.

Conclusions

Paediatric policies in the EU and the USA are only partially responsive to paediatric health needs. To be considered for wider implementation, paediatric incentives and obligations should be more targeted towards paediatric health needs. International harmonisation of legislation and alignment with global research priorities could further strengthen its impact on child health and support ongoing efforts to improve access to medicines. Furthermore, efforts should be made to ensure global access to authorised paediatric medicines.

Keywords: Therapeutics, Child Health, Health Policy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Paediatric legislation in the European countries and the USA has stimulated research and development of medicines for children. According to impact assessments, the number of paediatric medicines in these has increased. However, there are no studies to assess the potential impact on the childhood burden of disease beyond these countries and globally.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Emerging treatments do not reflect the disease burden in high-income countries and diverge even further from the needs in resource-constrained settings. Nevertheless, they offer more treatment options for select high-burden conditions, such as universally occurring infections and debilitating non-communicable diseases. They are also important contributors to the WHO lists of essential medicines. To achieve a better public health impact paediatric legislation should be expanded internationally, harmonised and tailored to global research priorities in children.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The study informs ongoing and future regulatory reform processes and especially the current revision of the EU Paediatric Legislation, to support the development of more impactful policies.

Introduction

Access to medicines remains a key priority of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aiming to secure healthy well-being.1 The SDGs recognise the need to promote research and development (R&D) of missing medicines and vaccines, especially for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 Children are particularly affected by the continuing lack of R&D and quality, safe and effective medicines globally.3–5 To improve paediatric care, the European Union (EU) and the USA introduced paediatric medicines legislation in 2007 and 1997, respectively. This legislation is based on a combination of obligations and incentives. Pharmaceutical companies are required to conduct paediatric investigations for new medicines including those intended for use in adults, receiving patent extensions in return.6 7 Research has shown that there has been an increase in paediatric labelling and formulations in both regions since the legislation was introduced.8–11 These findings suggest that similar legislation may be used to improve paediatric medicines availability and access in other regions.

However, one concern regarding EU/US paediatric legislation is that the paediatric R&D it encourages may not meet paediatric needs, thus limiting its practical benefits for paediatric care.9 Exploring the responsiveness of paediatric legislation to the health needs of children globally and in different countries is therefore crucial for understanding its potential for wider implementation. To our knowledge, there have been no systematic comparisons between paediatric medicines and paediatric needs beyond the implementing regions in relation to paediatric legislation so far. Addressing this gap, we map the spectrum of new paediatric medicines developed under paediatric legislation in the EU and USA to the burden of the target diseases in six countries of diverse income levels (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Kenya, Russia, South Africa) and globally. As a measure of disease burden, we use disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which quantify the loss of health by combining years of life lost plus years lived with disability.12 In addition, we assess the inclusion of the studied medicines in the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) as an indicator of their relevance to paediatric health needs relative to existing medical products. Based on this assessment, the paper examines the role of paediatric legislation for paediatric care in the international context.

Methods

Study context

This analysis is part of a larger study of paediatric regulatory policies and their implications for universal access. The selection of countries aimed for variability in geographical context, economic development, as well as regulatory and health systems. The selection was constrained by data collection considerations of the wider project, such as the availability of open-access data on medicine labelling (for more information, see Volodina et al 13). After an initial assessment, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Kenya, Russia and South Africa were selected for analysis. For the present paper, we applied a systematic mapping approach to ensure rigour, reduce bias and gain a comprehensive overview over the medicine development landscape under the EU/US legislation.

Sample of medicines developed under paediatric legislation

The medicines included in this review were identified from the open-access databases of medicines maintained by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA).14 15 The databases were downloaded and filtered for all medicines with approved indications resulting from paediatric development completed between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2018. Paediatric development was indicated by completed Paediatric Investigation Plans (EMA) or approved paediatric labelling (FDA). The variables required for this study (approved indications, approved formulations) were included in the FDA database, so no additional data extraction was necessary. For the EMA database, information regarding these variables had to be extracted by hand from the individual medicine’s entry on the EMA website.16 Data used for this analysis were cross-checked with other sources to ensure reliability. Lastly, medicines withdrawn for safety reasons, duplicates and medicines without an approved indication were excluded, and database entries that belonged to the same medicine were consolidated (for more information, see Volodina et al 13). For the present analysis, the sampling included medicines authorised in any EU country as opposed to only those approved in all EU countries, resulting in a larger sample than in Volodina et al.13 For the included medicines from the FDA, a random sample of 22% was drawn. The total sample comprised 195 medicines, 127 from the EU and 68 from the USA.

Indicators of the public health relevance

To assess the responsiveness of the EU/US paediatric legislation to paediatric health needs, we (1) mapped the sampled medicines to the DALYs of the target condition(s) and (2) reviewed their EML status.

The burden of disease assessment was based on DALY data from the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) results published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).17 The GBD results are organised hierarchically with mutually exclusive diseases or conditions that cause death or disability referred to as ‘DALY cause’. There are four hierarchical levels of DALY causes, starting with three categories at the first level: (1) communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional causes (CMNN); (2) non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and (3) injuries. The fourth level includes individual conditions or pooled categories as the most detailed causes. As example, see the levels for ‘typhoid fever’ provided in the ‘GBD concepts and terms defined’: ‘level 1: CMNN; level 2: enteric infections; level 3: typhoid and paratyphoid; level 4: typhoid fever’.18

The responsiveness to paediatric health needs considering existing treatments was assessed by reviewing medicines’ status in the WHO EML and the EML for children under 13 years of age (EMLc). Both EMLs have a core and a complementary list, representing the needs of basic and specialised healthcare systems, respectively.19

Data analysis

The sampled medicines were matched to the International Classification of Disease code corresponding to the target diseases using the open-access online electronic International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10).20 Code matching was based on the target disease in the approved indication with the ICD-10 code specification up to the first three or four characters. Medicines with more than one indication were matched with multiple ICD-10 codes.

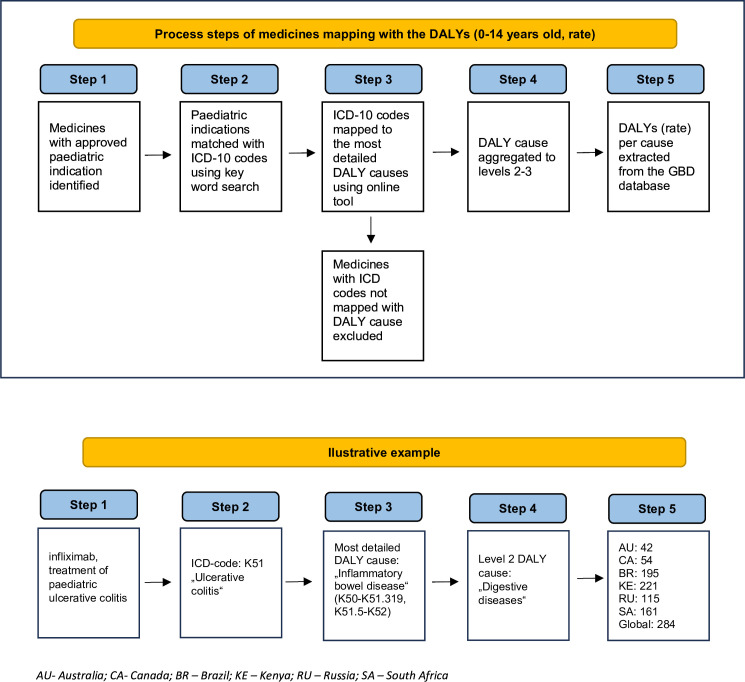

The codes obtained were mapped to the most detailed DALY causes in children (0–14 years, total DALYs and rate) for each country and globally. Mapping was done using the online IHME tool.21 The mapping process is shown in figure 1. The mapping results to the most detailed DALY causes can be found in online supplemental file 1).

Figure 1.

Process steps of medicines mapping to the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) with an illustrative example. GBD, Global Burden of Diseases; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision.

bmjpo-2023-002455supp001.pdf (148.4KB, pdf)

For analysis and reporting, the mapping results were aggregated to DALY cause level 2. For relevant compound level 2 categories, level 3 DALY causes were used instead to ensure sufficient detail (see table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of compound level 2 DALY causes and corresponding level 3 DALY causes used for mapping

| Compound level 2 DALY causes | Level 3 DALY causes used for mapping |

| Other non-communicable diseases | Congenital birth defects; urinary diseases and male infertility; gynaecological diseases; sudden infant death syndrome; oral disorders; endocrine, metabolic, blood and immune disorders; haemoglobinopathies and haemolytic anaemias |

| Respiratory infections and tuberculosis (TB) | Respiratory infections excl. TB; tuberculosis |

| Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and malaria | NTDs excl. malaria; malaria |

| HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) | STDs excl. HIV/AIDS; HIV/AIDS |

| Maternal and neonatal disorders | Maternal disorders; neonatal disorders |

DALY, disability-adjusted life year.

Results were calculated as percentages (proportions) according to the rounding rules and organised according to the level 1 DALY causes (tables 2–4). The colour code was generated automatically using the XLS function of conditional formatting.

Table 2.

Medicines for children (N=52) mapped to communicable diseases, maternal, neonatal disorders and nutritional (CMNN) diseases, with corresponding disease burden ranked by global burden

| DALYs per 100 000, 0–14 years, 2019 (% of total burden of DALYs attributed to CMNN diseases) | Mapped medicines, n (% of CMNN mapped medicines) | |||||||

| DALY cause | AU | BR | CA | KE | RU | SA | Global | |

| Neonatal disorders* | 1139 (69) |

5907 (66) |

1543 (76) |

9000 (34) |

1456 (52) |

10 669 (45) |

8883 (41) |

2 (4) |

| Respiratory infections excl. TB | 221 (13) |

1199 (13) |

226 (11) |

3330 (13) |

543 (20) |

2687 (11) |

3360 (15) |

16 (31) |

| Enteric infections | 76 (5) |

566 (6) |

139 (7) |

5238 (20) |

228 (8) |

2550 (11) |

3241 (15) |

6 (12) |

| Other infectious diseases | 81 (5) |

300 (3) |

71 (3) |

1856 (7) |

231 (8) |

1474 (6) |

1952 (9) |

19 (37) |

| Malaria* | <0.05 (0) |

7 (0) |

<0.05 (0) |

2450 (9) |

<0.05 (0) |

40 (0) |

1820 (8) |

2 (4) |

| Nutritional deficiencies | 117 (7) |

601 (7) |

53 (3) |

1705 (6) |

135 (5) |

1155 (5) |

1344 (6) |

1 (2) |

| STDs excl. HIV | 1 (0) |

37 (0) |

<0.05 (0) |

420 (2) |

2 (0) |

1321 (6) |

371 (2) |

2 (2) |

| HIV/AIDS* | 2 (0) |

79 (1) |

4 (0) |

1875 (7) |

150 (5) |

3072 (13) |

338 (2) |

15 (29) |

| Tuberculosis* | 1 (0) |

26 (0) |

1 (0) |

220 (1) |

16 (1) |

621 (3) |

311 (1) |

0 (0) |

| NTDs excl. malaria | 13 (1) |

171 (2) |

4 (0) |

241 (1) |

16 (1) |

96 (0) |

290 (1) |

0 (0) |

| Maternal disorders | <0.05 (0) |

3 (0) |

<0.05 (0) |

5 (0) |

<0.05 (0) |

<0.05 (0) |

4 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Total burden | 1651 | 8897 | 2041 | 26 340 | 2777 | 23 685 | 21 915 | |

| ||||||||

All DALY causes aggregated at the second level unless marked with *.

DALY source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

*DALY causes aggregated to the third level.

AU, Australia; BR, Brazil; CA, Canada; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; KE, Kenya; NTD, neglected tropical disease; RU, Russia; SA, South Africa; STD, sexually transmitted disease; TB, tuberculosis.

Table 3.

Medicines for children mapped to non-communicable diseases (NCDs; N=128) with corresponding disease burden ranked by global burden

| DALYs per 100 000, 0–14 years, 2019 (% of total burden of DALYs attributed to NCD) | Mapped medicines, n (% of mapped NCD medicines) | |||||||

| DALY cause | AU | BR | CA | KE | RU | SA | Global | |

| Congenital birth defects* | 720 (18) |

3077 (41) |

809 (21) |

1734 (34) |

1108 (27) |

1653 (35) |

2394 (38) |

2 (2) |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | 715 (18) |

735 (10) |

759 (20) |

601 (12) |

768 (19) |

504 (11) |

627 (10) |

13 (10) |

| Mental disorders | 822 (21) |

766 (10) |

625 (16) |

512 (10) |

491 (10) |

516 (11) |

587 (9) |

8 (6) |

| Neurological disorders | 317 (8) |

685 (9) |

330 (8) |

382 (8) |

314 (8) |

391 (8) |

433 (7) |

15 (12) |

| Neoplasms | 220 (6) |

484 (7) |

251 (6) |

295 (6) |

308 (8) |

173 (4) |

426 (7) |

10 (8) |

| Digestive diseases | 42 (1) |

195 (3) |

54 (1) |

221 (4) |

115 (3) |

161 (3) |

284 (4) |

10 (8) |

| Haemoglobinopathies and haemolytic anaemias* | 12 (0) |

79 (1) |

8 (0) |

189 (4) |

22 (1) |

34 (1) |

280 (4) |

3 (2) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 479 (12) |

461 (6) |

326 (8) |

273 (5) |

173 (4) |

340 (7) |

267 (4) |

13 (10) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 46 (1) |

222 (3) |

59 (2) |

187 (4) |

76 (2) |

159 (3) |

233 (4) |

7 (5) |

| Endocrine, metabolic, blood, immune disorders* | 167 (4) |

161 (2) |

134 (3) |

79 (2) |

154 (4) |

186 (4) |

159 (3) |

29 (23) |

| Sense organ diseases | 104 (3) |

147 (2) |

72 (2) |

196 (4) |

133 (3) |

197 (4) |

157 (2) |

12 (9) |

| Sudden infant death syndrome* | 102 (3) |

45 (1) |

68 (2) |

87 (2) |

102 (3) |

135 (3) |

125 (2) |

0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 126 (3) |

161 (2) |

218 (6) |

80 (2) |

160 (4) |

74 (2) |

123 (2) |

8 (6) |

| Diabetes and kidney disease | 25 (1) |

92 (1) |

39 (1) |

79 (2) |

61 (2) |

93 (2) |

122 (2) |

5 (4) |

| Oral disorders* | 50 (1) |

55 (1) |

50 (1) |

52 (1) |

57 (1) |

52 (1) |

54 (1) |

1 (1) |

| Urinary diseases and male infertility* | 8 (0) |

52 (1) |

9 (0) |

24 (0) |

14 (0) |

11 (0) |

35 (0.5) |

1 (1) |

| Gynaecological diseases* | 22 (1) |

24 (0) |

23 (1) |

25 (0) |

22 (1) |

22 (1) |

24 (0.3) |

1 (1) |

| Substance use disorders | 8 (0) |

5 (0) |

13 (0) |

2 (0) |

4 0) |

2 (0) |

3 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Total burden | 3985 | 7446 | 3847 | 5018 | 4082 | 4704 | 6333 | |

| ||||||||

All DALY causes aggregated at the second level unless marked with *.

DALY source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

*DALY causes aggregated to the third level.

AU, Australia; BR, Brazil; CA, Canada; DALY, daily-adjusted life year; KE, Kenya; RU, Russia; SA, South Africa.

Table 4.

Medicines for children (N=9) mapped to injuries with corresponding disease burden ranked by global burden

| DALYs per 100 000, 0–14 years, 2019 (% of total burden of DALYs attributed to injuries) | Mapped medicines, n (% of injury mapped medicines) | |||||||

| DALY cause | AU | BR | CA | KE | RU | SA | Global | |

| Unintentional injuries | 574 (74) |

838 (56) |

308 (57) |

659 (65) |

851 (67) |

923 (51) |

1107 (62) |

8 (89) |

| Transport injuries | 130 (17) |

371 (25) |

143 (26) |

217 (22) |

258 (20) |

555 (31) |

437 (25) |

0 (0) |

| Self-harm and interpersonal violence |

70 (9) |

279 (19) |

90 (17) |

133 (13) |

171 (13) |

321 (18) |

240 (13) |

1 (11) |

| Total burden | 774 | 1488 | 541 | 1009 | 1280 | 1799 | 1783 | |

| ||||||||

All DALY causes aggregated at the second level.

DALY source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

AU, Australia; BR, Brazil; CA, Canada; DALY, daily-adjusted life year; KE, Kenya; RU, Russia; SA, South Africa.

Mutually exclusive thematic categories were developed for medicines mapped with <0.05 DALYs to distinguish between global or national lack of measurable burden (table 5).

Table 5.

Medicines (N=28) for conditions with <0.05 DALYs (0–14 years) with thematic categories

| Thematic category | Paediatric indication | Medicines with respective indication, n |

| No measurable burden in all studied countries | Hypertension | 6 |

| Type II diabetes mellitus | 5 | |

| HPV infection | 2 | |

| Immediate reduction of blood pressure in hypertensive crisis | 1 | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 | |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | 1 | |

| Infantile haemangioma | 1 | |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | 1 | |

| No measurable burden in some studied countries | Poliomyelitis | 4 |

| Diphtheria | 4 | |

| Tetanus | 4 | |

| Treatment or prevention of hepatitis B | 6 | |

| Malaria | 2 | |

| Chronic hepatitis C | 1 |

DALY, daily-adjusted life year; HPV, human papillomavirus.

The international nonproprietary name search of the full sample was performed in the 23rd EML and the 9th EMLc from 2023. To account for the difference in the paediatric population between the EMLc (up to 13 years) and paediatric legislation (up to 18 years), and to capture essential medicines for adolescents, we included the EML in our review. When the EMLs included the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) subgroup as a therapeutic alternative, it was searched using the online ATC database.22 Assignment to the core or the complementary list was recorded.

Descriptive tables, figures and statistics were generated using MS Excel.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Burden of disease mapping

The 195 medicines were matched with 101 ICD-10 codes, allowing a DALY mapping for 187 medicines. For three ICD-10 codes, no DALY cause could be found in the online DALY tool, and eight medicines were excluded from the analysis (online supplemental file 2). In total, 61 (21%) of the 293 most detailed DALY causes were mapped to at least one medicine in the sample. A total of 128 medicines (68%) were mapped to NCDs which captured 21% of the global disease burden (30 031 DALYs). 52 medicines (28%) were mapped to CMNN diseases, which captured 73% of the global disease burden (21 915 DALYs). Two medicines with multiple indications were mapped to both, communicable and non-communicable disease groups. And lastly, nine medicines (5%) were mapped to injuries, which captured 6% (1783 DALYs) of the global disease burden.

bmjpo-2023-002455supp002.pdf (40.9KB, pdf)

In the following, we present the results of the systematic mapping of medicines to GBD DALYs by the three level 1 causes CMNN, NCDs and injuries in order of global disease burden (see tables 2–4).

Table 2 presents the mapping results for CMNN diseases and includes 52 medicines (28%) of all mapped medicines, of which 7 were mapped to more than one cause. The CMNN DALY cause with the highest burden across all countries and globally was ‘neonatal disorders’ with 8883 global CMNN DALYs (41% of all respective DALYs). It was mapped to 2 (2%) CMNN medicines, both Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccines. Malaria with 1820 (8%) global CMNN DALYs was mapped to two medicines, tuberculosis with 311 (1%) global CMNN DALYs and neglected tropical diseases with 290 (1%) global CMNN DALYs were mapped to none. Overall, ‘other infectious diseases’, ‘HIV/AIDS’ and ‘respiratory infections excl. TB’ were each mapped to 15 or more medicines, by far the highest number. ‘Other infectious diseases’ with 1952 (9%) global CMNN DALYs was mapped to 19 (37%) CMNN medicines. 12 of them were for hepatitis B or C, bacteraemia, cytomegalovirus and invasive fungal infections, and 7 were multicomponent childhood vaccines.

Table 2 also shows that middle-income countries bear a higher burden of infectious diseases, nutritional deficiencies and neonatal disorders.

Table 3 presents the DALY mapping for NCDs, which includes 128 (68%) of medicines, of which 9 are mapped to more than one cause. The burden of disease distribution did not reveal striking differences between the countries or globally. The DALY cause with the highest burden was ‘congenital birth defects’ with 2394 (38%) NCD DALYs globally. It was mapped to two medicines for paediatric glaucoma. Several high-burden DALY causes were well represented in the sample, such as ‘skin and subcutaneous diseases’ with 627 (10%) global NCD DALYs and 13 (10%) NCD treatments, ‘neurological disorders’ with 443 (7%) global NCD DALYs and 15 (12%) NCD treatments. However, most NCD medicines (23%) were mapped to the DALY cause of endocrine, metabolic, blood and immune disorders (‘EMBI’), which accounted for 3% of NCD DALYs globally. The most targeted ‘EMBI’ indications were anaemia, rare coagulation and metabolic disorders.

For several NCD DALY causes at levels 2 and 3, medicines were indicated for a few conditions. For example, in ‘musculoskeletal disorders’, seven out of eight medicines were for juvenile arthritis. In ‘chronic respiratory diseases’, eight medicines were for allergic rhinitis and the remaining five for asthma. ‘Diabetes and kidney diseases’ was mapped exclusively to insulins.

Table 4 shows the mapping results for the level 1 DALY group ‘Injuries’, which was mapped with 9 (5%) of all mapped medicines. Eight medicines addressed complications of medical treatment and were mapped to ‘unintentional injuries’. One medicine in the ‘self-harm and interpersonal violence’ was indicated to prevent organ transplant rejection. The DALY distribution for injuries was higher in the middle-income countries.

In total, 28 medicines were mapped to DALY causes at the most detailed level that had a negligible burden of disease (<0.05 DALYs) (see table 5). 18 of these medicines targeted conditions uncommon in children in all studied countries and globally. These were either generally rare diseases (eg, rare tumour), diseases that primarily affect the adult population but are uncommon in children (eg, hypertension), or human papillomavirus vaccines.

10 medicines were mapped to diseases with a lack of measurable burden in some countries, namely in Australia and Canada.

WHO EMLs review results

Of all 195 sampled medicines, 67 (34%) were found in the EMLc and 93 (48%) in the WHO EML (see table 6), with most medicines included in the core lists. The largest groups were childhood and influenza vaccines, antivirals and antifungals, human immunoglobulins, medicines for blood disorders and antiretrovirals. Of the 26 medicines included only in the EML, 7 were for adolescent use for mental disorders, emergency contraception or HIV/AIDS pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Table 6.

WHO essential medicines list inclusion of sampled medicines for children (N=195)

| WHO list inclusion | Number of medicines, n (%) |

| Medicines included in the EMLc, 2023 | 67 (34) |

| Out of them: | |

| Medicines in the core list | 45 |

| Of these, included as therapeutic alternatives | 11 |

| Medicines in the complementary list | 22 |

| Of these, included as therapeutic alternatives | 5 |

| Medicines included in the EML, 2023 | 93 (48) |

| Out of them: | |

| Medicines in the core list | 67 |

| Of these, included as therapeutic alternatives | 22 |

| Medicines in the complementary list | 26 |

| Of these, included as therapeutic alternatives | 7 |

EML, Essential Medicines List; EMLc, Essential Medicines List for children.

Discussion

Our study shows that the sampled medicines developed under paediatric legislation in the EU and USA are a heterogeneous group with limited responsiveness to children’s health needs. Overall, we found a disproportionate focus on NCDs, many of which have a high burden on adults but not on children. Conversely, we found few medicines that address high-burden paediatric diseases, particularly childhood infections. Still, the inclusion of about a third of the sampled medicines in the WHO EMLc suggests that there has been a relevant contribution to paediatric care. Finally, the study identified high-burden diseases with available treatments where access remains limited.

Mismatch between disease burden and spectrum of medicines

Our findings support previous evidence on the limited alignment between R&D and paediatric needs in the EU and the USA itself, including the bias towards therapeutic areas with relevant adult indications.23 Studies conducted after the adoption of the EU/US legislation have shown persisting off-labelling prescribing across therapeutic areas.24 25 This evidence, together with our study, suggests that while paediatric legislation may have addressed the needs of children to some extent, significant gaps remain. The lack of paediatric treatments for poverty-related diseases shows that the gap between the needs and research efforts is most pronounced for children in LMICs.

The focus on areas with adult indications found in our study echoes the fact that paediatric legislation requires developers to assess the potential of medicines primarily developed for adults for their use in children. However, this policy approach is limited by the lack of alignment between research efforts and health needs of children and adults in general. A study by the US Congressional Budget Office suggested that instead of health needs, R&D investment decisions are based on expected sales, R&D costs and local policies.26 A study analysing the pharmaceutical pipeline from 2006 to 2011 found that 26% of 2477 medicines were indicated for neoplasms, followed by diseases of the nervous system and sense organs (13%), infectious and parasitic diseases (11%) and EMBI disorders (9%).27 These figures are echoed in the distribution of medicines in our study and do not reflect the spectrum of the global burden of disease, in adults or children.28

Advancing regulatory policies for children

Our results show that there have been some relevant contributions to paediatric care since the implementation of the EU/US paediatric policies. As such, paediatric policies may be a promising policy tool to improve availability of appropriate paediatric medicines, provided they are modified to be more needs-oriented. Such changes would also be beneficial in regions where paediatric legislation is already in place. For example, the European Commission has recently proposed variable data protection periods depending on the unmet needs addressed by the medicine.29 Such measures could strengthen the responsiveness of paediatric legislation to paediatric health needs and encourage research into conditions relevant to children. Ideally, the assessment of unmet needs underlying variable protection periods or other measures tied to paediatric needs should be based on a global assessment of paediatric needs. In addition, the introduction of paediatric legislation in countries outside of the EU and USA should include the harmonisation of regulatory obligations and rewards to enhance compliance and impact.30 Nonetheless, fostering needs-driven R&D for paediatric medicines requires complementary financing mechanisms directed at the development of original paediatric medicines beyond the scope of paediatric legislation. This could be particularly relevant for off-patent medicines where the incentives of the EU legislation were shown to be insufficient.23 Efforts to define missing medicines were undertaken in the past31 32 and could serve as a sound basis for policy development in this area. Finally, alongside with regulatory policies, global initiatives and research collaborations such as the Global Accelerator for Paediatric Formulations Network and the International Neonatal Consortium will continue to play a critical role in facilitating development and access to paediatric medicines.33 34

Our study also highlights that successful drug development does not always result in practical use. For example, Australia and Canada were the only countries with a negligible burden of vaccine-preventable diseases in our study. These findings underscore the relevance of health system and other barriers that affect access to existing medicines, particularly in LMICs.35 Reducing access barriers and increasing coverage of approved medicines is therefore critical. The same applies to access to surgery, mental health services and other non-pharmacological interventions, which may be required to address some of the included paediatric conditions, such as injuries, congenital birth defects or mental disorders. Our findings also underscore the relevance of diseases related to poor living conditions and unhealthy environments, including enteric infections and nutritional deficiencies. Addressing these requires the provision of access to safe water and sanitation, food security and health education. Public health interventions beyond pharmaceutical policies thus remain indispensable in reducing paediatric disease burden and need to continue.36 37

Strengths and limitations

Our study provides important insights into the responsiveness of paediatric legislation to paediatric health needs in countries with diverse disease burden and globally. The study is the first to systematically compare paediatric R&D to paediatric health needs, despite more than a decade since the implementation of paediatric legislation. It offers relevant and novel insights into the potential gains and limitations of paediatric legislation and can support policy-making decisions in the EU and beyond.

This study has several limitations. The exclusion of contraceptives and symptomatic treatments, that is, pain killers, and the paediatric age group from 15 to 18 years of age from the DALYs mapping may have underestimated the responsiveness of the studied medicines sample to paediatric needs. Some DALY causes, such as injuries, frequently require non-pharmaceutical interventions or surgeries, which may explain the small number of medicines in the sample for such causes. Medicines approved after 2018 were not analysed. The EU/US orphan drug legislation38 may have contributed to the high number of medicines for low-burden diseases, obscuring the relationship to paediatric legislation. Moreover, while our results examine the scope of medicines developed under the paediatric legislation, the lack of a comparison to paediatric R&D before policy implementation limits our ability to assess the direct effect of the legislation. Finally, limitations associated with the use of DALYs apply.39 Research in other geographical regions is recommended to further refine policy recommendations.

Conclusion

Medicines developed under the paediatric legislation in the EU and USA are only partially responsive to paediatric health needs and exhibit a disproportionate focus on NCDs. To be considered for wider implementation, paediatric incentives and obligations should therefore be more targeted towards paediatric health needs. International harmonisation of legislation and alignment with global research priorities could further strengthen its impact on child health and support ongoing efforts to improve access to authorised treatments. Finally, health interventions beyond improving access to medicines are needed to achieve a global reduction of paediatric disease burden.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For the publication fee we acknowledge financial support by Heidelberg University

Footnotes

Contributors: AV contributed to conceptualisation, carried out data collection, analysis and interpretation, drafted the initial paper, and reviewed and agreed on the final version. RJ contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, reviewed and revised the manuscript and agreed on the final version. AJ contributed to conceptualisation, reviewed, commented and agreed on the final version of the manuscript. AV accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: No, there are no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. United Nations . Sustainable development goals: goal 3. health – United Nations sustainable development. n.d.

- 2. United Nations . Sustainable development goals: goal 3. health, target 3B– United Nations sustainable development. n.d.

- 3. Moulis F, Durrieu G, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Off-label and unlicensed drug use in children population. Therapie 2018;73:135–49. 10.1016/j.therap.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vieira I, Sousa JJ, Vitorino C. Paediatric medicines – regulatory drivers, restraints. Opportunities and Challenges J Pharm Sci 2021;110:1545–56. 10.1016/j.xphs.2020.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van der Veken M, Brouwers J, Budts V, et al. Practical and operational considerations related to Paediatric oral drug formulation: an industry survey. Int J Pharm 2022;618:121670. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Commission Regulation (EC) no 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for Paediatric use and amending regulation (EEC). European Commission 2006:EUR–Lex. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Food and Drug Administration . Fact sheet: pediatric provisions in the food and Drug Administration safety and innovation act (FDASIA). n.d. Available: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/food-and-drug-administration-safety-and-innovation-act-fdasia/fact-sheet-pediatric-provisions-food-and-drug-administration-safety-and-innovation-act-fdasia

- 8. Rocchi F, Paolucci P, Ceci A, et al. The European Paediatric legislation: benefits and perspectives. Ital J Pediatr 2010;36:56. 10.1186/1824-7288-36-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. European Medicines Agency. 10-year Report to the European Commission . General report on the experience acquired as a result of the application of the Paediatric regulation 10-year report to the European Commission (core report); 2017. Available: uropa.eu [Accessed 5 Dec 2021].

- 10. Thaul S. FDA’s authority to ensure that drugs prescribed to children are safe and effective. 2012. Available: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL33986.pdf [Accessed 18 Dec 2020].

- 11. Toma M, Felisi M, Bonifazi D, et al. TEDDY European network of excellence for Paediatric research. Paediatric medicines in Europe: the Paediatric regulation-is it time for reform. Front Med 2021:593281. 10.3389/fmed.2021.593281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Disability-adjusted life years (Dalys). Available: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/158 [Accessed 17 Jan 2023].

- 13. Volodina A, Shah-Rohlfs R, Jahn A. Does EU and US Paediatric legislation improve the authorization availability of medicines for children in other countries Br J Clin Pharmacol 2023;89:1056–66. 10.1111/bcp.15553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. European Medicines Agency . Paediatric investigation plans - download table. download medicine data. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/download-medicine-data [Accessed 17 May 2021].

- 15. Food and Drug Administration . Web BPCA PREA Pediatric Labelling and Studies report, Available: https://www.fda.gov/media/151598/download [Accessed 21 Oct 2021].

- 16. European Medicines Agency . Medicines. Medicines | European Medicines Agency (europa.eu),

- 17. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network . Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019). Seattle, United States: Institute for health Metrics and evaluation (IHME). 2020. Available: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd

- 18. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global burden of disease (GBD) data and tools guide. Available: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/about-gbd [Accessed 17 Dec 2023].

- 19. World Health Organization . Expert Committee on selection and use of essential medicines. Available: https://www.who.int/groups/expert-committee-on-selection-and-use-of-essential-medicines [Accessed 17 Feb 2023].

- 20. World Health . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision. Available: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/enAccessed [Accessed 17 Feb 2023].

- 21. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . Global burden of disease study 2019(GBD 2019) cause list mapped to ICD codes. n.d. Available: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2019-cause-icd-code-mappings

- 22. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics and Methodology . ATC/DDD index 2023. 2023. Available: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 23. European Commission . Commission staff working document. joint evaluation of regulation (EC) no 1901/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for Paediatric use and regulation (EC) no 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999. 2020. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-08/orphan-regulation_eval_swd_2020-163_part-1_0.pdf [Accessed 18 Feb 2023].

- 24. Netherlands Institute For Health Services Research . Study on off-label use of medicinal products in the European Union. 2017. Available: https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Report_OFF_LABEL_Nivel-RIVM-EPHA.pdf [Accessed 17 Feb 2023].

- 25. Allen HC, Garbe MC, Lees J, et al. Off-label medication use in children, more common than we think: A systematic review of the literature. J Okla State Med Assoc 2018;111:776–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Congressional Budget . Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry, . 2021. Available: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57025 [Accessed 20 Feb 2023].

- 27. Fisher JA, Cottingham MD, Kalbaugh CA. “Peering into the pharmaceutical “pipeline”: investigational drugs, clinical trials, and industry priorities”. Soc Sci Med 2015;131:322–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milne CP, Kaitin KI. Are regulation and innovation priorities serving public health needs Front Pharmacol 2019;10:144. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. European . Reform of the EU Pharmaceutical Legislation, . 2023. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/pharmaceutical-strategy-europe/reform-eu-pharmaceutical-legislation_en [Accessed 30 Apr 2023].

- 30. Volodina A, Jahn A, Jahn R. Suitability of Paediatric legislation beyond the United States and Europe: a qualitative study on access to Paediatric medicines. Bmjph 2024;2:e000264. 10.1136/bmjph-2023-000264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization . Priority medicines for Europe and the world / Warren Kaplan, Richard Laing. World Health Organization; 2004. Available: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/68769.Accessed [Google Scholar]

- 32. United Nationscommission on life-saving commodities for women and children. 2012. Available: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Final%20UN%20Commission%20Report_14sept2012.pdf [Accessed 30 Apr 2023].

- 33. Lewis T, Wade KC, Davis JM. Challenges and opportunities for improving access to approved neonatal drugs and devices. J Perinatol 2022;42:825–8. 10.1038/s41372-021-01304-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Penazzato M, Watkins M, Morin S, et al. Catalysing the development and introduction of Paediatric drug formulations for children living with HIV: a new global collaborative framework for action. Lancet HIV 2018;5:e259–64. 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30005-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ozawa S, Shankar R, Leopold C, et al. Access to medicines through health systems in Low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2019;34:iii1–3. 10.1093/heapol/czz119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stevenson M, Yu J, Hendrie D, et al. Reducing the burden of road traffic injury: translating high-income country interventions to middle-income and low-income countries. Inj Prev 2008;14:284–9. 10.1136/ip.2008.018820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gallegos D, Eivers A, Sondergeld P, et al. Food insecurity and child development: A state-of-the-art review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:17.:8990. 10.3390/ijerph18178990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. European Commission . Regulation(EC)No 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32000R0141&from=EN [Accessed 23 Feb 2023].

- 39. Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Diseases and injuries collaborators. global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjpo-2023-002455supp001.pdf (148.4KB, pdf)

bmjpo-2023-002455supp002.pdf (40.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.