Abstract

Introduction

Chronic inflammation plays a key role in knee osteoarthritis pathophysiology and increases risk of comorbidities, yet most interventions do not typically target inflammation. Our study will investigate if an anti-inflammatory dietary programme is superior to a standard care low-fat dietary programme for improving knee pain, function and quality-of-life in people with knee osteoarthritis.

Methods and analysis

The eFEct of an Anti-inflammatory diet for knee oSTeoarthritis study is a parallel-group, assessor-blinded, superiority randomised controlled trial. Following baseline assessment, 144 participants aged 45–85 years with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis will be randomly allocated to one of two treatment groups (1:1 ratio). Participants randomised to the anti-inflammatory dietary programme will receive six dietary consultations over 12 weeks (two in-person and four phone/videoconference) and additional educational and behaviour change resources. The consultations and resources emphasise nutrient-dense minimally processed anti-inflammatory foods and discourage proinflammatory processed foods. Participants randomised to the standard care low-fat dietary programme will receive three dietary consultations over 12 weeks (two in-person and one phone/videoconference) consisting of healthy eating advice and education based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines, reflecting usual care in Australia. Adherence will be assessed with 3-day food diaries. Outcomes are assessed at 12 weeks and 6 months. The primary outcome will be change from baseline to 12 weeks in the mean score on four Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) subscales: knee pain, symptoms, function in daily activities and knee-related quality of life. Secondary outcomes include change in individual KOOS subscale scores, patient-perceived improvement, health-related quality of life, body mass and composition using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, inflammatory (high-sensitivity C reactive protein, interleukins, tumour necrosis factor-α) and metabolic blood biomarkers (glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), insulin, liver function, lipids), lower-limb function and physical activity.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received ethics approval from La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee. Results will be presented in peer-reviewed journals and at international conferences.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12622000440729.

Keywords: knee, chronic disease, rehabilitation medicine, nutrition & dietetics

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The anti-inflammatory dietary programme was codeveloped and piloted with patients and clinicians, with the comparison low-fat dietary programme representing usual care.

Sufficiently powered trial evaluating change from baseline to 12 weeks (primary endpoint) and 6 months facilitating longer-term effectiveness evaluation of the anti-inflammatory dietary programme.

This trial will evaluate both self-reported and objective outcomes to understand potential mechanisms of symptomatic changes.

While outcome assessors are blinded to group allocation, the health professionals delivering the interventions and participants are unable to be blinded to group allocation due to the type of interventions.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common rheumatic disease affecting approximately 15% of the population, with OA of the knee being most prevalent.1 2 Knee OA and its associated symptoms can be disabling and lead to substantial societal and healthcare costs.3 In Australia alone, annual OA-related healthcare expenditure exceeds $AUD2.1 billion.4 Although the main symptom of knee OA is pain, individuals with knee OA have an increased risk of other chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes.5 As many as two-thirds of older adults with knee OA have more than one comorbidity.6

Clinical guidelines for knee OA recommend exercise therapy and weight loss as first-line management strategies due to their excellent safety profile and therapeutic effects similar to commonly used analgesics.3 7 However, the effectiveness of exercise therapy has recently been questioned due to its lack of benefit over an open-label placebo,8 and findings that one-third of people completing an exercise programme do not achieve a clinically meaningful improvement in pain.9 10 Weight loss programmes in those who are overweight or obese typically consist of caloric-restrictive diets, which are challenging to adhere to and sustain.11 A meta-analysis highlighted that, within 2 years of a calorie-restrictive programme, over half of initial weight lost was regained, and by 5 years, this figure jumped to >80%.12

Anti-inflammatory diets provide an alternative to calorie-restrictive approaches by targeting local and systemic inflammation, both contributors to OA disease onset, progression and symptom burden.13–15 Anti-inflammatory diets are typically high in minimally processed, nutrient rich foods such as fruit, vegetables, spices and extra virgin olive oil, which are dense in nutrients such as polyphenols, carotenoids, fibre, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids.16–19 These nutrients can significantly reduce inflammation even in the absence of weight loss20 via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties by neutralising free radicals and associated cell damage, as well as improved lipid profiles.16 17 21 Omega-3 fatty acids, abundant in nuts, seeds and fish, are also a key part of anti-inflammatory dietary approaches and help to achieve a more desirable omega-6 to omega-3 ratio.22 In contrast, omega-6 fatty acids can be converted into arachidonic acid, a precursor for proinflammatory eicosanoids.23 An elevated omega-6:omega-3 ratio exacerbates oxidative stress, which increases the risk and severity of chronic disease, including OA.15 Due to their focus on real foods and consumption to satiety, anti-inflammatory diets are likely more sustainable than traditional calorie-restrictive approaches.17

Anti-inflammatory diets have garnered much interest in recent years due to their effectiveness in alleviating symptoms and improving biomarkers for a variety of chronic diseases, including diabetes,18 cardiovascular disease,24 epilepsy25 and rheumatoid arthritis.26 Small studies investigating anti-inflammatory diets for knee OA have demonstrated feasibility and effectiveness in reducing symptoms and inflammation over 12–16 weeks.15 27 28 To date, no fully powered randomised controlled trial (RCT) has evaluated the effectiveness of an anti-inflammatory diet in knee OA.

The primary aim of this RCT is to estimate the average effect of an anti-inflammatory dietary programme compared with a standard care low-fat dietary programme on knee-related pain, function and quality of life in individuals with knee OA. We hypothesise that the anti-inflammatory dietary programme will result in greater improvements in knee-related pain, function and quality of life after 12 weeks (primary endpoint) and 6 months (secondary endpoint) compared with the standard care low-fat dietary programme. Secondary aims are to assess 12-week and 6-month effectiveness of the anti-inflammatory dietary programme on (1) self-reported global rating of change and achievement of acceptable symptoms; (2) health-related quality of life; (3) body mass and composition using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and (4) inflammatory and metabolic blood biomarkers, global lower-limb function and physical activity.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This protocol describes a pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group assessor-blinded superiority RCT and will be reported according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statement.29 Reporting of the completed RCT will conform to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement.30 The FEAST (eFEct of an Anti-inflammatory diet for knee oSTeoarthritis) trial will be conducted at a single site (La Trobe University) in Melbourne, Australia with the first participant randomised on 31 August 2022 and the final participant anticipated to be randomised in June 2024. The primary endpoint will be at 12 weeks, with additional follow-up at 6 months (further longer-term follow-up dependent on funding). The study was prospectively registered on the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN 12622000440729).

Patient and public involvement

Participants and clinicians codesigned the anti-inflammatory intervention, research questions and study methods. This input was gained from (1) qualitative interviews with participants from the pilot study as part of formal process evaluation strategies28; (2) participant and clinician focus groups providing feedback on study recruitment material and participant handbooks and (3) discussion with experienced clinicians managing knee OA and dietary intervention strategies as part of FEAST development. Patients and clinicians will provide input into the dissemination of study results by assisting with the decision on what information to share and in what format.

Participants

144 adults 45–85 years old with chronic knee pain consistent with a clinical OA diagnosis using criteria from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which does not require radiographic evidence,31 will be enrolled (table 1).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

Fulfil National Institute for Health and Care Excellence31 clinical criteria for osteoarthritis:

|

Another reason than OA for knee symptoms (eg, tumour, fibromyalgia) |

| Age ≤85 years—due to potential safety reasons and additional comorbidities that may hinder capacity for dietary adherence | Planning to have knee surgery in next 6 months |

| History of knee pain on most days of the past month | Already strictly following an anti-inflammatory diet (eg, low carbohydrate, paleo, Mediterranean) |

| History of knee pain for at least 3 months | Following a habitual diet that excludes animal products (eg, vegan) |

| Be willing and able to attend 3–4 phone consults and 12-week and 6-month follow-up assessments | Unable to follow anti-inflammatory diet (eg, medically contraindicated, history of food allergy/hypersensitivity, family reasons) |

| Able to understand written and spoken English and to give informed consent | Taking the following diabetic medication that affects blood sugar levels (ie, insulin, SGLT 2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas) to mitigate the risk of hypoglycaemia/ketoacidosis |

| Contraindications for DXA scans (eg, pregnant, breast feeding, planning pregnancy in next 6 months, >200 kg body weight) | |

| >5 kg weight fluctuation in past 3 months (ie, unstable weight) | |

| Unable to understand written and spoken English | |

| Knee injection, injury or surgery in the past 3 months | |

| A diagnosed psychiatric disorder (excluding anxiety and depression) | |

| History of eating disorder or bariatric surgery | |

| Had all eligible knee joints replaced by arthroplasty |

DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; OA, osteoarthritis; SGLT, sodium glucose co-transporter.

Recruitment and screening procedure

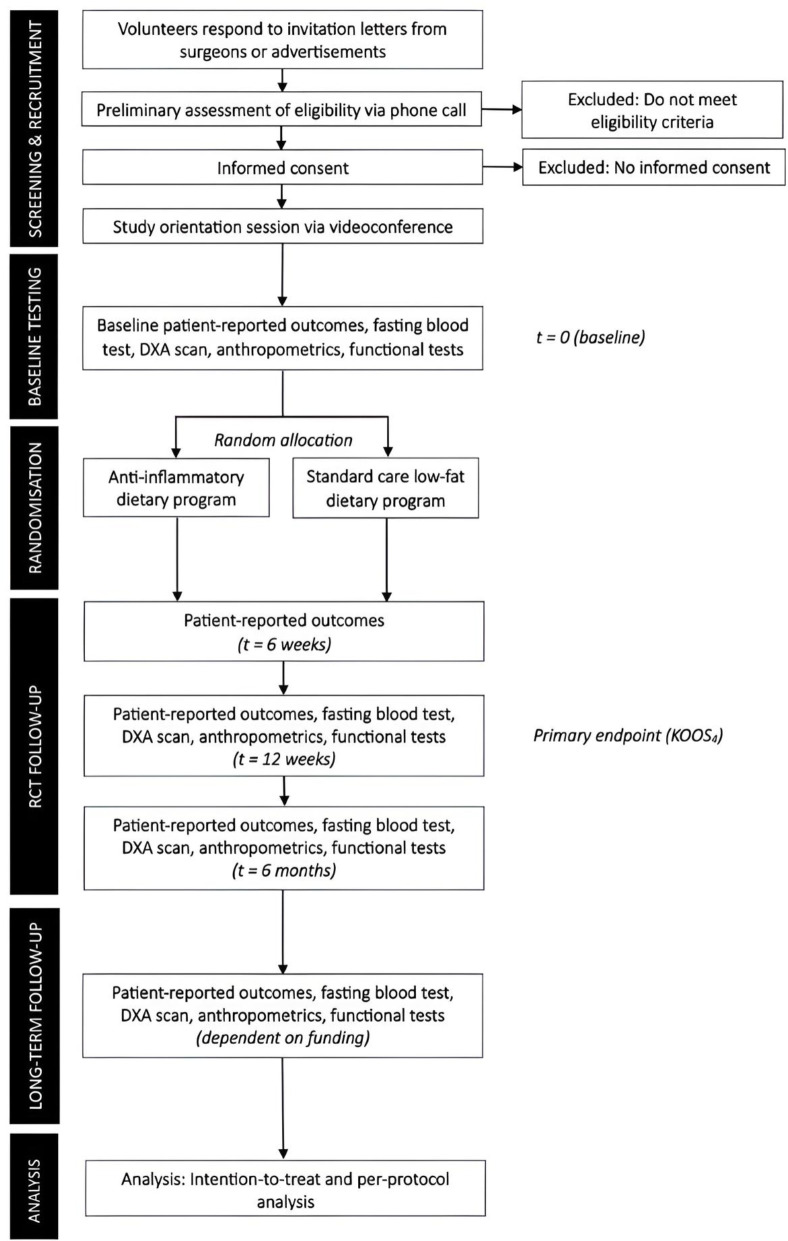

Trial flow is outlined in figure 1. Participants will be recruited from our network of collaborating orthopaedic surgeons in Victoria, Australia. Consistent with our prior work in other musculoskeletal conditions,32 33 potentially eligible participants (ie, individuals aged 45–85 years with a history of knee pain for which medical care was sought) will be sent a study information letter inviting them to contact the research team. Additional recruitment strategies will include advertisements in local newspapers, community/university magazines/posters, community market stalls and social media.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the trial. DXA, dual X-ray absorptiometry; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score. Optional qualitative interview for process evaluation at 6 months.

Potential participants will be screened for eligibility via telephone. Once eligibility is confirmed, participants will attend a study orientation session via videoconference to explain further study details (eg, fasting requirements) and be orientated to the dietary assessment tool (3-day food diary). If both knees meet the inclusion criteria, the most symptomatic knee will be considered as the index knee.

Randomisation procedure, concealment of allocation and blinding

On completion of baseline assessment, participants will be randomised to either the anti-inflammatory dietary programme or standard care low-fat dietary programme. Study treatments, but not study hypotheses, will be revealed to participants. A computer-generated randomisation schedule has been developed a priori by an independent statistician in random permuted blocks of 4–8 and stratified by sex and body mass index (≥30 kg/m2 vs <30 kg/m2). To ensure concealed allocation, the randomisation schedule will be stored electronically in the secure Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system and only accessible to an unblinded researcher once baseline measures have been obtained, who will communicate treatment allocation to the participant. Investigators conducting the follow-up assessments will be blinded to group allocation. As the primary outcome is self-reported, participants are considered assessors; therefore, they will be blinded to previous scores. The health professionals delivering the interventions will deliver the intervention for both groups. Specific protocols for both interventions (including consultation contents and format, and accompanying resources) have been developed, and the health professionals have received training to ensure equal credibility. Random observations of intervention delivery will be conducted by the principal investigators to ensure treatment delivery credibility and fidelity.

An independent statistician, blinded to group allocation, will perform the primary RCT analysis.

Interventions

The anti-inflammatory dietary programme and standard care low-fat dietary programme are summarised aligning to Template for Intervention Description and Replication guidelines34 (table 2). Participants in both intervention groups were not actively discouraged to lose weight, but weight loss was described as a potential outcome of the interventions. The same health professionals will deliver the intervention for both groups.

Table 2.

Overview of intervention delivery described according to the TIDieR guidelines

| Brief name | Anti-inflammatory dietary programme | Standard care low-fat dietary programme |

| WHY | Anti-inflammatory diets targeting systemic inflammation assist in the prevention and management of various chronic diseases.16 Small pilot studies have shown a positive effect of anti-inflammatory diets to improve knee-related symptoms in people with knee osteoarthritis.28 | Healthy eating guidelines and dietary advice described in the standard care programme booklet was based on Australian Dietary Guidelines (ADGs).37 68

2–3 dietetic consultations represent usual care for patients referred for dietary management in Australia.37 38 |

| WHAT (MATERIALS) | Participants receive an intervention handbook containing all study details, key anti-inflammatory eating principles, example meal plans, traffic light system of foods encouraged and discouraged, and education (eg, common myths, tips for eating out, shopping tips); complimentary access to the Defeat Diabetes programme app/website; complimentary links to three movies; and a complimentary copy of the book ‘A Fat Lot of Good’.35 | Participants receive an educational handbook emphasising ADGs healthy eating principles and are provided links to the online resources from the Eat for Health website (https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/). |

| WHAT (PROCEDURES) | Six consultations providing individualised guidance and support to follow an anti-inflammatory eating pattern, emphasising the consumption of fruits, non-starchy vegetables, fish, poultry, red meat, eggs, full-fat dairy, nuts, seeds and extra virgin olive oil. Participants will be encouraged to avoid highly processed foods, refined carbohydrates, added sugar and processed meats. | Three consultations providing general advice and education regarding healthy eating based on the ADGs. The principles focus on consumption of foods from the five food groups, while limiting intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars and alcohol. |

| WHO PROVIDED | A qualified dietitian or health professional specially trained to deliver all components. | A qualified dietitian or health professional specially trained to deliver all components. |

| HOW | Delivered with individual support for 12 weeks, after which, participants will be encouraged to sustain the anti-inflammatory diet unsupported up to 6 months. Consultations are one to one. | Delivered with standard healthy eating advice for 12 weeks, after which, participants will be encouraged to sustain the programme unsupported up to 6 months. Consultations are one to one. |

| WHERE | In-person consultations will occur at La Trobe University Nutrition and Dietetics research laboratory. Additional consultations will occur via telephone/videoconference (eg, Zoom). Participants will integrate the diet principles into their daily consumption of foods and beverages. | In-person consultations will occur at the La Trobe University Nutrition and Dietetics research laboratory. Additional consultations will occur via telephone/videoconference (eg, Zoom). Participants will integrate the diet principles into their daily consumption of foods and beverages. |

| WHEN AND HOW MUCH | Two in-person consultations at baseline (~45 min) and week 12 (~30 min) Four phone/videoconference follow-up consultations (~30 min) in weeks 2, 4, 6 and 9. Total active intervention delivery time: ~3.5 hours Participants are provided with self-management resources to optimise adherence to the anti-inflammatory diet up to the 6-month follow-up. |

Two in-person consultations at baseline (~45 min) and week 12 (~30 min) One phone/videoconference follow-up consultation (30 min) in week 6. Total active control delivery time: ~1.5 hours Participants encouraged to sustain their diet up to 6 month follow-up. |

| TAILORING | Individualised anti-inflammatory dietary advice, education and support aligning with participant preferences and goals. | Advice based on the ADGs. |

| MODIFICATIONS | Any modifications will be reported. | |

| HOW WELL (planned) | 2–3 professionals (qualified dietitian and other health professional) receive prior training in how to deliver and supervise the programme. Fidelity is assessed through random auditing by members of the principal investigator team (AGC or BLD). Participant adherence to the anti-inflammatory diet is assessed through consultation attendance, regular 3-day food diaries and self-report. | 2–3 professionals (qualified dietitian and health professional) receive prior training in how to deliver and supervise the programme. Fidelity is assessed through random auditing by members of the principal investigator team (AGC or BLD). Participant adherence to the standard care low-fat diet is assessed through consultation attendance, regular 3-day food diaries and self-report. |

| HOW WELL (actual) | This will be reported in the primary paper. | |

TIDieR, Template for Intervention Description and Replication.;

Anti-inflammatory dietary programme

Participants allocated to the anti-inflammatory dietary programme will receive specific anti-inflammatory dietary education and an individualised eating plan, as well as a suite of resources to support behaviour change. The anti-inflammatory dietary programme will be delivered over 12 weeks by a qualified dietitian or by another health professional specially trained to deliver the intervention (eg, physiotherapist).

Participants will be encouraged to follow a diet containing minimally processed foods and vegetable oils, and higher amounts of healthy fats and nutrient-dense wholefoods known to fight inflammation (eg, fresh fruits low in natural sugar such as berries, non-starchy vegetables, nuts and seeds, seafood, poultry, red meat, eggs, full-fat dairy). Healthy fats include monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats with optimal omega-3: omega-6 ratios as found in seafood, nuts and extra virgin olive oil. Participants will be advised to limit processed foods, refined carbohydrates (eg, pasta, bread, rice), confectionary and foods with added sugar. Participants will be encouraged to consume a normocaloric diet and to eat to satiety, with no specific percentage of total energy intake targets for carbohydrate, fat or protein.

An initial in-person consultation (~45 min) will occur immediately following group allocation to constructively review participant’s current dietary intake (using baseline 3-day food diary) and develop an individualised meal plan. Participants will be provided with a comprehensive explanation of anti-inflammatory dietary principles, its rationale (eg, the role of inflammation in OA, link between foods and inflammation) and its potential benefits and side effects, and address questions and/or concerns. The following educational and behaviour change resources will also be provided at the initial consultation to support adherence: (1) bespoke information booklet providing anti-inflammatory eating information, example meal plans and foods that are encouraged and foods to avoid (online supplemental files 1 and 2); (2) complimentary subscription to an anti-inflammatory programme (Defeat Diabetes phone app/website), providing anti-inflammatory recipes, masterclasses, meal plans and educational articles; (3) complimentary links to recommended documentaries exploring the benefits of anti-inflammatory nutrition (ie, Fat Fiction, Cereal Killers, That Sugar Film) and (4) complimentary copy of a book exploring benefits of anti-inflammatory approach (A Fat Lot of Good35).

bmjopen-2023-079374supp001.pdf (13MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-079374supp002.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

Follow-up phone/videoconference consultations (~30 min) will be scheduled in weeks 2, 4, 6 and 9, with timing to be negotiated between each participant and the health professional delivering the intervention. A final in-person consultation will be delivered immediately following the completion of the 12-week assessment. These follow-up consultations will provide participants with ongoing support, education and accountability. A 3-day food diary, completed prior to each consultation (see outcomes/adherence section), will guide individualised feedback and support to adapt meal plans to optimise adherence.

Standard care low-fat dietary programme

Participants allocated to the standard care low-fat dietary programme will receive advice and education regarding healthy eating based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines.36 These government-endorsed guidelines aim to optimise nutrition intake through adequate consumption of foods from the five core food groups (grains and cereals; fruit; vegetables and legumes; lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs and tofu; reduced fat diary or alternatives), while limiting intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars and alcohol. They are high-carbohydrate and low-fat focused—participants will be encouraged to include at least four serves of wholegrains daily (eg, brown rice, pasta, bread, quinoa, oats) and to choose low-fat protein and dairy foods where possible.

The programme will be delivered through individual consultations with the treating dietitian or other specially trained health professional—the first in-person consultation immediately following baseline assessment (~45 min), the second via phone/videoconference at 6 weeks (~30 min) and the third in-person at 12-week follow-up with timing individualised as required. Two to three consultations represent usual care for patients referred for dietary management in Australia through the current public healthcare (Medicare) rebate system.37 38 During the initial in-person consultation, participants will be provided with a bespoke educational booklet and advice and education emphasising the Australian Dietary Guideline principles (https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines) and informed of complementary and publicly available online resources from the Eat for Health website (https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/).

The follow-up phone/videoconference consultation in week 6 and in-person follow-up in week 12 will provide participants with ongoing support, education and accountability. The 3-day food diary, completed prior to each consultation (see outcomes/adherence section), will guide feedback and support to adapt meal plans to optimise adherence. The treating health professionals delivering the two dietary programmes will be based centrally at La Trobe University and will be trained by the senior study dietitian (BLD) until deemed competent in intervention delivery.

Irrespective of group allocation, participants can continue usual medical care and consult with their treating health professionals as necessary (eg, general practitioner regarding medication changes).

Data collection procedure

Data will be collected at baseline and 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months after randomisation, with 12 weeks the a priori primary endpoint as this coincides with completion of supported interventions (table 3). Where possible, data will be collected and managed using a secure web-based software platform (REDCap) hosted at La Trobe University,39 which has equivalent measurement properties to paper-based completion.40 This strategy was used in our pilot study28 and other trials of musculoskeletal conditions.41 Paper versions will also be available if preferred.

Table 3.

Overview of data collection

| Variable | Baseline | 6 weeks | 12 weeks | 6 months |

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Age | X | |||

| Sex and gender | X | |||

| Ethnicity | X | |||

| Education level | X | |||

| Health literacy (REALM) | X | |||

| Employment status | X | |||

| Smoking status | X | |||

| Civil status, living situation | X | |||

| Medical history, comorbidities | X | |||

| Knee pain/injury/surgery history | X | |||

| Objective clinical outcomes | ||||

| Height, weight, waist girth | X | X | X | |

| 30 s chair stand test | X | X | X | |

| 40 m walk test | X | X | X | |

| Body composition (DXA) | X | X | X | |

| Blood inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers | X | X | X | |

| Blood pressure | X | X | X | |

| Patient-reported Outcomes | ||||

| KOOS subscales | X | X | X | X |

| Global rating of change | X | X | X | |

| Desire for knee surgery | X | X | X | X |

| Medication use | X | X | X | X |

| Knee pain (current and worst in past week) | X | X | X | X |

| EQ-5D-5L* | X | X | X | X |

| Patient acceptable symptom state | X | X | X | X |

| Brief Pain Inventory | X | X | X | |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) | X | X | X | |

| 3-day food diaries† | X | X | X | X |

| Adverse events | X | X | X |

*Assesses health-related quality of life across five dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) and a Visual Analogue Scale (0–100) of current overall health status.

†3-day food diaries are also assessed prior to anti-inflammatory dietary programme consultations at 2, 4 and 9 weeks.

DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; REALM, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine.

Outcomes

Baseline characteristics

Participant characteristics including age, sex, ethnicity, knee pain/surgery details, socioeconomic details (eg, education level, employment status, living status), medical history and health literacy (assessed with the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine42) will be collected (table 3).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the change from baseline to 12 weeks in the mean score on four Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) subscales covering knee pain, symptoms, function in daily activities and knee-related quality of life. The KOOS is a 42-item patient-reported outcome measure assessing five separately scored subscales: Pain, Symptoms, Function in Sport and Recreation (Sport/Rec), Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Quality of Life. The KOOS4 and all KOOS subscale scores range from 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). The KOOS is a valid, responsive and reliable questionnaire, with KOOS4 a primary outcome for other knee OA trials.33 43 44

Secondary effectiveness outcomes

KOOS subscales

To allow for clinical in-depth interpretation, scores for the five KOOS subscales will be reported individually (ie, pain, symptoms, function in sports and recreational activities, ADL, quality of life).10 44

Global Rating of Change and patient-acceptable state

Self-perceived change in pain and function will be assessed using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘much worse’ to ‘much better’ in response to the questions: ‘Overall, how has your knee pain changed since the start of the study?’ and ‘Overall, how has your knee function changed since the start of the study?’, respectively. Treatment success will be defined as a response of either ‘better’ or ‘much better’. Satisfaction with current knee function using the self-reported Patient Acceptable Symptom State question.45 Participants not satisfied with current knee function at follow-up assessments will be asked a second question to determine if they considered the treatment to have failed.45

Anthropometrics

Height and weight will be assessed using a seca 217 stadiometer and seca 703 EMR-validated column scale (Hammer Steindamm, Hamburg, Germany), respectively. Waist circumference will be measured using a metal tape measure (Lufkin W606PM ¼ inch×2 m Executive Thinline Pocket Tape).

Global lower-limb function

Two performance-based tests of lower-limb function recommended by the OA Research Society International will be conducted: the 30 s chair-stand test (number of chair-stands from a standardised height chair in 30 s) and 40 m walk test (time to walk 40 m safely, using walking aids if required).46

Body composition

A whole-body DXA scan will be acquired using a Hologic Horizon DXA scanner (Bedford, Massachusetts, UA) to assess adiposity (visceral, peripheral) and lean mass.47

Inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers

An array of blood inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers will be analysed from samples of blood collected, including high sensitivity C reactive protein, cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α), blood glucose, HbA1c, serum insulin, liver function tests (including albumin) and lipids (eg, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides). Participants will be instructed to fast for at least 10 hours prior to blood collection and a single forearm venepuncture will take place to collect a total of ≤30 mL blood. Plasma and serum samples will be centrifuged (3000 ms, 10 min) and all samples (plasma, serum and whole blood) frozen at −80°C for later analysis (online supplemental file 3).

bmjopen-2023-079374supp003.pdf (131.4KB, pdf)

Secondary safety outcomes

Adverse events

Adverse events and serious adverse events will be recorded at 6-week, 12-week and 6-month follow-up via open probe questioning to optimise collection of sufficient detail. Under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses harms statement, an adverse event is defined as any undesirable experience causing participants to seek medical treatment (eg, general practitioner).48 A serious adverse event is defined as any undesirable event/illness/injury classified as having the potential to significantly compromise clinical outcome or result in significant disability or incapacity, those requiring inpatient or outpatient hospital care, to be life-threatening or result in death.

Exploratory outcomes

Dietary analysis

Participants will record food and beverage intake over 3 days via the smartphone application Australia Calorie Counter—Easy Diet Diary (Xyris Software) or on paper (personal preference). Easy Diet Diary is a commercial calorie counter and food diary that allows users to email recorded diaries to treating professionals. Once received by the treating health professional, the 3-day food diaries will be imported into and analysed using, Foodworks Premium Edition nutrient analysis software (V.10, Brisbane, Australia 2019) and Australian food composition databases. Paper-based 3-day food diaries will be manually entered into FoodWorks. Total energy intake, macronutrients, micronutrients and core food group analysis will be reported. Dietary analysis data will also be used to calculate the inflammatory potential of participants’ diets (eg, Dietary Inflammatory Index).49

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life will be assessed with the EQ-5D-5L generic health index, which comprises five dimensions of health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, anxiety or depression) and a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) of current overall health status.50 Both validity and reliability has been demonstrated in arthritic populations.51

Knee pain and interference

Self-reported knee pain (current, worst over past week, average over past week) will be assessed using a 100 mm VAS (0=no pain, 100=worst pain imaginable). The degree to which knee pain interferes with participant’s daily functioning will be assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory,52 a tool with reliability and validity demonstrated in knee pain populations.53 54

Change in analgesic medication use

Change in analgesic medication use from baseline to 12-week and 6-month follow-up will be assessed with a 7-point Likert scale (much less to much more).

Physical activity

Physical activity will be assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ),55 a standardised and valid questionnaire providing an estimate of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, which has been widely validated.55–57 Respondents are asked to report time spent in physical activity across three intensities (walking, moderate, vigorous). Using the IPAQ scoring protocol,58 total weekly physical activity can be estimated by weighting time spent in each activity intensity with its estimated metabolic equivalent energy expenditure.59

Blood pressure

A pair of seated blood pressure measurements will be obtained using an automated monitor (Omron Model HEM-7121). The blood pressure cuff is placed over the mid-upper arm with the participant seated.

Self-perceived wellness

Self-reported sleep quality, hunger, fatigue and energy levels will be assessed using a 100 mm VAS (0=worst outcome, 100=best outcome).

Intervention adherence

Adherence will be assessed by a self-reported VAS (0=not at all adherent, 100=extremely adherent) and 5-point Likert scale at 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months and evaluation of 3-day food diaries by consulting health professionals. Satisfactory adherence is defined as a self-report of both ≥80 on the VAS and ‘Most days’ or ‘Every day’ on the Likert scale, at both the 6-week and 12-week time points.

Data management

Most outcome data will be collected and managed electronically via REDCap web-based software hosted at La Trobe University. Other data (eg, DXA reports) will be stored electronically on the La Trobe University secure research drive. All electronic data will be deidentified (participant code) and exported for data analysis and saved in a password-protected database on the La Trobe University research drive only accessible to the research team. Paper-based identifying documents (eg, consent forms) will be securely stored in a locked filing cabinet accessible only to members of the research team and separately from reidentifiable (ie, coded) data.

Due to the minimal known risks associated with the interventions being evaluated, our study will not have a formal data monitoring committee and will not require an interim analysis. This is the same approach we have taken with other low-risk RCTs.41 Any unexpected serious adverse events or outcomes will be discussed by the trial management committee (authors of this protocol) and reported to the approving human research ethics committee for monitoring.

Sample size calculation

This trial has been powered to detect a clinically significant between-group difference for the primary outcome of KOOS4. A recent RCT comparing an anti-inflammatory diet versus low-caloric diet in overweight women with knee OA observed an effect size (standardised mean difference) on self-reported pain and function of 1.0 (95% CI 0.5 to 1.6).60 Given inherent differences in the FEAST RCT (eg, Australian Dietary Guideline control group, not specifically targeting overweight participants, inclusion of both women and men), we used the lower bound 95% CI to provide a conservative estimate of the anticipated effect size (0.5). This estimated effect size is also a conservative estimate based on our single-arm anti-inflammatory diet pilot trial, which had an effect size of 0.68.28 Recruiting 128 participants (equally distributed between two arms) would yield 80% power to observe such an effect or larger at a two-tailed type I error of 0.05. This sample size estimation is also conservative since it is based on independent samples t-test. Using an Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model that includes the baseline value as a covariate and is prespecified for the analysis should provide higher power for the same sample size.61 To account for a potential 10% drop-out, we will recruit 144 participants. This sample size will also be sufficient to detect a minimal important change in KOOS4 estimated at 10 points in patients with knee OA (with a common between-subject SD of 15).62

Statistical analyses

Analysis will be performed according to the estimands framework63 with a statistical analyst blinded to group allocation. All outcomes and analyses are prospectively categorised as primary, secondary or exploratory. For the primary hypothesis, a linear model with baseline value, sex and BMI (≥30 vs <30 kg/m2) as covariates and treatment condition as a fixed factor will evaluate the treatment effect on the primary outcome of KOOS4 (mean score of four of the five subscales of the KOOS) at 12 weeks. A linear mixed model utilising repeated measures at all time points for secondary hypotheses will allow non-biased estimates of treatment effect in the presence of any potential missing cases, providing data are missing at random. A sensitivity analysis using pattern-mixture model to investigate the deviation from the missingness-at-random assumption will be carried out.64 For secondary binary outcomes (eg, treatment success), mixed-effect logistic regression models will be used to assess the effect of treatment. A subsequent analysis of participants classified as adherent to the protocol will be performed. Following publication of the primary trial results, we will also perform a formal mediation analysis to estimate direct and indirect (eg, through weight and inflammation change) effects.

Healthcare resource use

Healthcare resource utilisation (eg, hospitalisations, medical imaging, healthcare visits, medication use) will be assessed by participant self-report to estimate costs associated with the trial programmes (eg, hospital admissions, medication use, clinician visits, imaging tests, out-of-pocket expenses).

Process evaluation

Semistructured interviews will be conducted on a subset of consenting participants (until data saturation is reached) at 6 months. Interviews will explore experiences, knowledge and understanding of interventions received including potential benefits; acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the intervention and reasons for adhering (or not) to the allocated diet. Purposive sampling will be used to recruit interview participants based on characteristics (anti-inflammatory dietary programme vs standard care low-fat dietary programme, men vs women) and outcomes of the trial (good outcome vs poor outcome). Interviews will be audio recorded, transcribed and analysed using framework analysis,65 a flexible technique allowing researchers to identify, compare and contrast data according to inductively and deductively derived themes. Data will be coded and an inductive thematic analysis will be applied until no new themes emerge.

Ethics and dissemination

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and has received approval from La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (HEC-22044). Written informed consent will be obtained from participants prior to enrolment (online supplemental file 4). Anti-inflammatory diets are associated with minimal and transient adverse events, thus there are minimal safety considerations associated with this trial.

bmjopen-2023-079374supp004.pdf (198.5KB, pdf)

Study outcomes will be widely disseminated through a variety of sources. Results will be reported in peer-reviewed publications and presented at key national and international conferences. Only aggregate data will be reported. A lay summary report will be available for study participants. Any important protocol amendments will be reported to the approving ethics committee, registered at ANZCTR and communicated in the primary RCT paper. Any serious adverse events will be recorded and reported to the approving ethics committee.

Deidentified data will be made available on reasonable request to the principal investigator (AGC) after publication (except where the sharing of data is prevented by privacy, confidentiality, or other ethical matters, or other contractual or legal obligations) according to La Trobe University Research Data Management Policy.

Discussion

The current RCT will be the first full-scale trial to evaluate the symptomatic, inflammatory, functional and body composition benefits of an anti-inflammatory dietary programme compared with a standard care low-fat dietary programme based on Australian Dietary Guidelines. While outcome assessors are blinded to group allocation, owing to the type of interventions (ie, dietary advice) blinding of participants will not be possible. We also acknowledge that, like most RCTs, there is a risk that our recruitment strategy may result in a selected sample not representative of the general population. However, using similar recruitment strategies, our prior RCTs have resulted in a representative sample of the culturally and sociodemographically diverse Australian population that has similar characteristics to other international cohorts with the index musculoskeletal condition.66

The evaluation of a non-pharmacological anti-inflammatory dietary programme to improve pain, symptoms and quality of life for individuals with OA could have important individual and socioeconomic benefits—decreased healthcare dollars spent on managing OA and reduced surgery waiting lists. Another benefit is that anti-inflammatory diets are also effective at combating metabolic syndrome, a key risk factor for chronic diseases, and thus the benefits from treating OA could stretch further to improving other medical comorbidities.67 This fully powered RCT represents a crucial step towards the development of a sustainable and cost-effective therapy that can both supplement and complement existing treatment strategies to optimise OA outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank La Trobe University Medical Centre for assistance with blood collection, La Trobe Nutrition and Dietetics department for the use of the nutrition lab and DXA scanner, and Melbourne Pathology for providing pathology collection kits and analysis of biomarkers from blood specimens.

Footnotes

Twitter: @jheerey, @JoanneLKemp, @AndreaBMosler

Contributors: AGC, BLD, PB and JLK conceived the study and obtained funding. AGC, BLD, PB and JLK designed the study protocol with input from LL, JJH and ABM. ADL provided statistical expertise and will conduct primary statistical analysis. MH provided blood analysis expertise and will lead inflammatory and metabolic marker analyses. HGM and NPW assisted with participant recruitment from their clinical population with knee osteoarthritis. LL drafted the manuscript with input from AGC, JJH, BLD, PB, JLK, AA, MDH, ADL, ABM, HGM and NPW. All authors and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This trial is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia through an Investigator Grant held by AGC (GNT2008523), an Investigator Grant held by JLK (APP2017844), and a philanthropic donation from PB.

Competing interests: PB is the founder of Defeat Diabetes and author of 'A Fat Lot of Good'. PB contributed to study design but has no role in study execution, data management, analysis or the decision to publish. The NHMRC has no role in study design and will not have any role in its execution, data management, analysis and interpretation or on the decision to submit the results for publication. JLK is an editor of the British Journal of Sports Medicine (British Medical Journal Group). AGC is an associate editor of British Journal of Sports Medicine (British Medical Journal Group). All other authors have no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Cui A, Li H, Wang D, et al. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020;29–30:100587. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duong V, Oo WM, Ding C, et al. Evaluation and treatment of knee pain. JAMA 2023;330:1568–80. 10.1001/jama.2023.19675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weng Q, Goh S-L, Wu J, et al. Comparative efficacy of exercise therapy and oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol for knee or hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2023;57:990–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ackerman I, Bohensky M, Pratt C, et al. Counting the cost: part 1 Healthcare costs. The Current and Future Burden of Arthritis 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams A, Kamper SJ, Wiggers JH, et al. Musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Med 2018;16:167. 10.1186/s12916-018-1151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pihl K, Roos EM, Taylor RS, et al. Associations between comorbidities and immediate and one-year outcomes following supervised exercise therapy and patient education - A cohort study of 24,513 individuals with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021;29:39–49. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, et al. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:622–36. 10.1002/art.38290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henriksen M, Hansen JB, Klokker L, et al. Comparable effects of exercise and Analgesics for pain secondary to knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of trials included in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Comp Eff Res 2016;5:417–31. 10.2217/cer-2016-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barton CJ, Kemp JL, Roos EM, et al. Program evaluation of GLA:D® Australia: physiotherapist training outcomes and effectiveness of implementation for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2021;3:100175. 10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roos EM, Grønne DT, Skou ST, et al. Immediate outcomes following the GLA:D® program in Denmark, Canada and Australia. A longitudinal analysis including 28,370 patients with symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021;29:502–6. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das SK, Gilhooly CH, Golden JK, et al. Long-term effects of 2 energy-restricted diets differing in Glycemic load on dietary adherence, body composition, and metabolism in CALERIE: a 1-Y randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1023–30. 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity. Med Clin North Am 2018;102:183–97. 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ansari MY, Ahmad N, Haqqi TM. Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoarthritis pathogenesis: role of Polyphenols. Biomed Pharmacother 2020;129:S0753-3322(20)30645-4. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011;23:471–8. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strath LJ, Jones CD, Philip George A, et al. The effect of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on pain in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med 2020;21:150–60. 10.1093/pm/pnz022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galbete C, Kröger J, Jannasch F, et al. Nordic diet, Mediterranean diet, and the risk of chronic diseases: the EPIC-Potsdam study. BMC Med 2018;16:99. 10.1186/s12916-018-1082-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of Omega-6/Omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother 2002;56:365–79. 10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00253-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, et al. A journey into a Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008222. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hussain T, Tan B, Yin Y, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation: what Polyphenols can do for us Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016;2016:7432797. 10.1155/2016/7432797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neale EP, Batterham MJ, Tapsell LC. Consumption of a healthy dietary pattern results in significant reductions in C-reactive protein levels in adults: a meta-analysis. Nutr Res 2016;36:391–401. 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ciaffi J, Mitselman D, Mancarella L, et al. The effect of Ketogenic diet on inflammatory arthritis and cardiovascular health in rheumatic conditions: A mini review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:792846. 10.3389/fmed.2021.792846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Russo GL. Dietary N-6 and N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: from Biochemistry to clinical implications in cardiovascular prevention. Biochem Pharmacol 2009;77:937–46. 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ricker MA, Haas WC. Anti-inflammatory diet in clinical practice: A review. Nutr Clin Pract 2017;32:318–25. 10.1177/0884533617700353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li J, Lee DH, Hu J, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of cardiovascular disease among men and women in the U.S. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2181–93. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. D’Andrea Meira I, Romão TT, Pires do Prado HJ, et al. Ketogenic diet and epilepsy: what we know so far. Front Neurosci 2019;13:5. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schönenberger KA, Schüpfer A-C, Gloy VL, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory diets on pain in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021;13:4221. 10.3390/nu13124221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dyer J, Davison G, Marcora SM, et al. Effect of a Mediterranean type diet on inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers in patients with osteoarthritis. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:562–6. 10.1007/s12603-016-0806-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooper I, Brukner P, Devlin BL, et al. An anti-inflammatory diet intervention for knee osteoarthritis: a feasibility study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:47. 10.1186/s12891-022-05003-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) . National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Guermazi A, et al. Early knee osteoarthritis is evident one year following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:946–55. 10.1002/art.39005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Guermazi A, et al. Early Patellofemoral osteoarthritis features one year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: symptoms and quality of life at three years. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:784–92. 10.1002/acr.22761 Available: https://acrjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/21514658/68/6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (Tidier) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:bmj.g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brukner DP. A fat lot of good. 1st edn. Penguin Australia Pty Ltd, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. National Health and Medical Research Council . Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra (Australia): National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cant RP. Patterns of delivery of Dietetic care in private practice for patients referred under Medicare chronic disease management: results of a national survey. Aust Health Rev 2010;34:197–203. 10.1071/AH08724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spencer L, O’Shea MC, Ball L, et al. Attendance, weight and waist circumference outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes receiving Medicare-subsidised Dietetic services. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:291–7. 10.1071/PY13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The Redcap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:S1532-0464(19)30126-1. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gudbergsen H, Bartels EM, Krusager P, et al. Test-retest of computerized health status questionnaires frequently used in the monitoring of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized crossover trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:190. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Culvenor AG, West TJ, Bruder AM, et al. Supervised exercise-therapy and patient education rehabilitation (SUPER) versus minimal intervention for young adults at risk of knee osteoarthritis after ACL reconstruction: SUPER-Knee randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2023;13:e068279. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med 1991;23:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Skou ST, Roos EM, Laursen MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1597–606. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Collins NJ, Prinsen CAC, Christensen R, et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2016;24:1317–29. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant States in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the patient acceptable symptom state. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:34–7. 10.1136/ard.2004.023028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2013;21:1042–52. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shepherd JA, Ng BK, Sommer MJ, et al. Body composition by DXA. Bone 2017;104:101–5. 10.1016/j.bone.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zorzela L, Loke YK, Ioannidis JP, et al. PRISMA harms checklist: improving harms reporting in systematic reviews. BMJ 2016;352:i157. 10.1136/bmj.i157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, et al. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1689–96. 10.1017/S1368980013002115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1717–27. 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hurst NP, Kind P, Ruta D, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: validity, responsiveness and reliability of Euroqol (EQ-5D). Br J Rheumatol 1997;36:551–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/36.5.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mendoza T, Mayne T, Rublee D, et al. Reliability and validity of a modified brief pain inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur J Pain 2006;10:353–61. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roth SH, Fleischmann RM, Burch FX, et al. Around-the-clock, controlled-release Oxycodone therapy for osteoarthritis-related pain: placebo-controlled trial and long-term evaluation. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:853–60. 10.1001/archinte.160.6.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country Reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maddison R, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y, et al. International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) and New Zealand physical activity questionnaire (NZPAQ): a doubly labelled water validation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:62. 10.1186/1479-5868-4-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cleland C, Ferguson S, Ellis G, et al. Validity of the International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) for assessing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour of older adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:176. 10.1186/s12874-018-0642-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sjostrom M, Ainsworth BE, Bauman A, et al. Guidelines for data processing analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) - Short and long forms. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:S498–504. 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dolatkhah N, Toopchizadeh V, Barmaki S, et al. The effect of an anti-inflammatory in comparison with a low caloric diet on physical and mental health in overweight and obese women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Nutr 2023;62:659–72. 10.1007/s00394-022-03017-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens WAJG. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:1234–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Silva MDC, Perriman DM, Fearon AM, et al. Minimal important change and difference for knee osteoarthritis outcome measurement tools after non-surgical interventions: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023;13:e063026. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lynggaard H, Bell J, Lösch C, et al. Principles and recommendations for incorporating Estimands into clinical study protocol Templates. Trials 2022;23:685. 10.1186/s13063-022-06515-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. White IR, Kalaitzaki E, Thompson SG. Allowing for missing outcome data and incomplete uptake of randomised interventions, with application to an Internet‐Based alcohol trial. Stat Med 2011;30:3192–207. 10.1002/sim.4360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ritchie J, Spencer L, eds. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. 2002. 10.4135/9781412986274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Culvenor AG, West TJ, Bruder AM, et al. Recruitment and baseline characteristics of young adults at risk of early-onset knee osteoarthritis after ACL reconstruction in the SUPER-knee trial. BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Peiris CL, Culvenor AG. Metabolic syndrome and osteoarthritis: implications for the management of an increasingly common phenotype. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023;31:1415–7. 10.1016/j.joca.2023.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wingrove K, Lawrence MA, Russell C, et al. Evidence use in the development of the Australian dietary guidelines: A qualitative study. Nutrients 2021;13:3748. 10.3390/nu13113748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-079374supp001.pdf (13MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-079374supp002.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-079374supp003.pdf (131.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-079374supp004.pdf (198.5KB, pdf)