Abstract

The importance of chemoreflex function for cardiovascular health is increasingly recognized in clinical practice. The physiological function of the chemoreflex is to constantly adjust ventilation and circulatory control to match respiratory gases to metabolism. This is achieved in a highly integrated fashion with the baroreflex and the ergoreflex. The functionality of chemoreceptors is altered in cardiovascular diseases, causing unstable ventilation and apnoeas and promoting sympathovagal imbalance, and it is associated with arrhythmias and fatal cardiorespiratory events. In the last few years, opportunities to desensitize hyperactive chemoreceptors have emerged as potential options for treatment of hypertension and heart failure. This review summarizes up to date evidence of chemoreflex physiology/pathophysiology, highlighting the clinical significance of chemoreflex dysfunction, and lists the latest proof of concept studies based on modulation of the chemoreflex as a novel target in cardiovascular diseases.

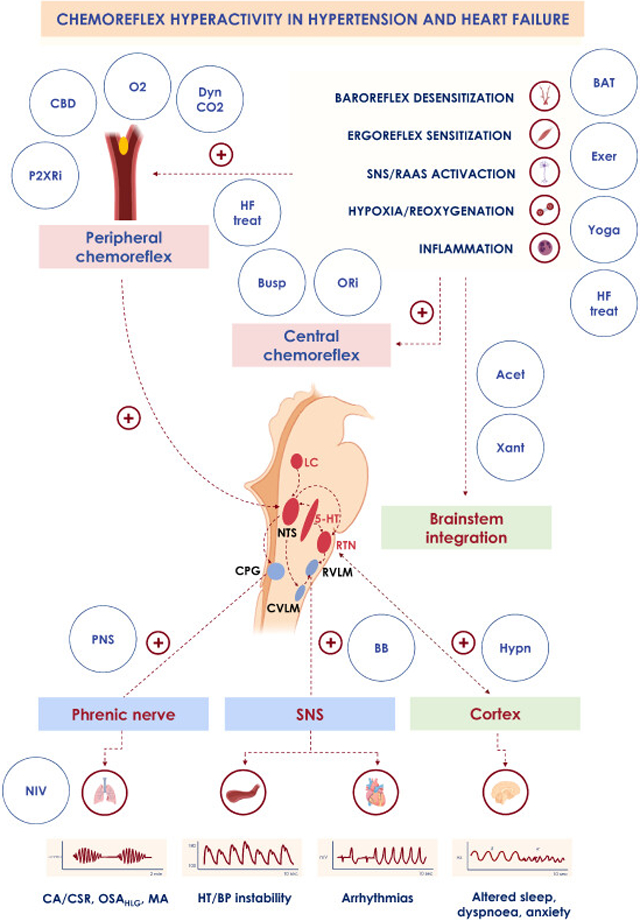

Graphical Abstract

Clinical conditions associated with chemoreflex overactivity.

Decreased baroreflex sensitivity, increased ergoreflex sensitivity, increased sympathetic drive, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation, phasic hypoxia/reoxygenation and inflammation that occurs in hypertension (HT) and heart failure (HF) promote increased peripheral and central chemosensitivity, leading to adverse clinical consequences, such as ventilatory instability, apnoeas (central apnoeas [CA], high loop gain obstructive apnoeas [OSAHLG], mixed apnoeas [MA]), increased and unstable blood pressure (BP), increased arrhythmic risk, arousability, dyspnoea and anxiety. Several treatments may act directly or indirectly on the chemoreflex system to reset a physiologic autonomic and respiratory equilibrium, with positive effects on the cardiovascular system.

Acet: acetazolamide; BAT: baroreflex activation therapy; BB: beta-blockers; Busp: buspirone; CBD: carotid body denervation; CPG: central pattern generator; Dyn CO2: dynamic carbon dioxide administration; Exer: exercise; HCSB: Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes breathing; CVLM: caudal ventrolateral medulla; HF treat: heart failure treatment; Hypn: hypnotics; 5-HT: 5-hydroxytryptamine neurons (serotonergic); Xant: xantines; LC: locus coeruleus; O2: oxygen administration; ORi: orexin inhibitors; P2XRi: P2X receptor inhibitors; NIV: non invasive ventilation; NTS: nucleus tractus solitarii; PNS: phrenic nerve stimulation; RTN: retrotrapezoid nucleus; RVLM: rostral ventrolateral medulla; SNS: sympathetic nervous system.

1. Introduction

The chemoreflex is a closed loop reflex, which physiologically adjusts ventilation in response to hypoxia or hypercapnia.1,2 It also matches ventilation with end-organ perfusion by altering sympatho-vagal balance, in concert with high and low pressure baroreflexes and ergoreflex.1

If the chemoreflex is dysregulated, either because of an increased or decreased activity, cardiorespiratory control misaligns, resulting in hyper- or hypoventilation, periodic breathing and apnoeas, sympathetic nervous system overactivation and life-threatening arrhythmias, hypo- or hypertension,1,3 and increased likelihood of fatal apnoeas after seizures.4

In cardiovascular diseases, the prevalence and prognostic relevance of chemoreflex dysfunction makes it a promising therapeutic target.3,5 Some novel treatment options are already available for conditions in which the chemoreflex is overactive, such as hypertension, apnoeas and heart failure (HF),3,5,6 while interventions to stimulate hypoactive chemoreceptors, mainly in neurological diseases,7 have not as yet been studied systematically.

This Review will summarize up to date evidence of chemoreflex pathophysiology, highlight the clinical significance of chemoreflex dysfunction, and list the latest proof of concept studies based on chemoreflex modulation as a novel target in cardiovascular diseases.

2. Chemoreflex physiology

A detailed description of chemoreflex physiology has been reviewed elsewere1 and is beyond the scope of this review. In summary, there are two principal sets of chemoreceptors (CR): peripheral and central CR (Figure 1 and Table 1).

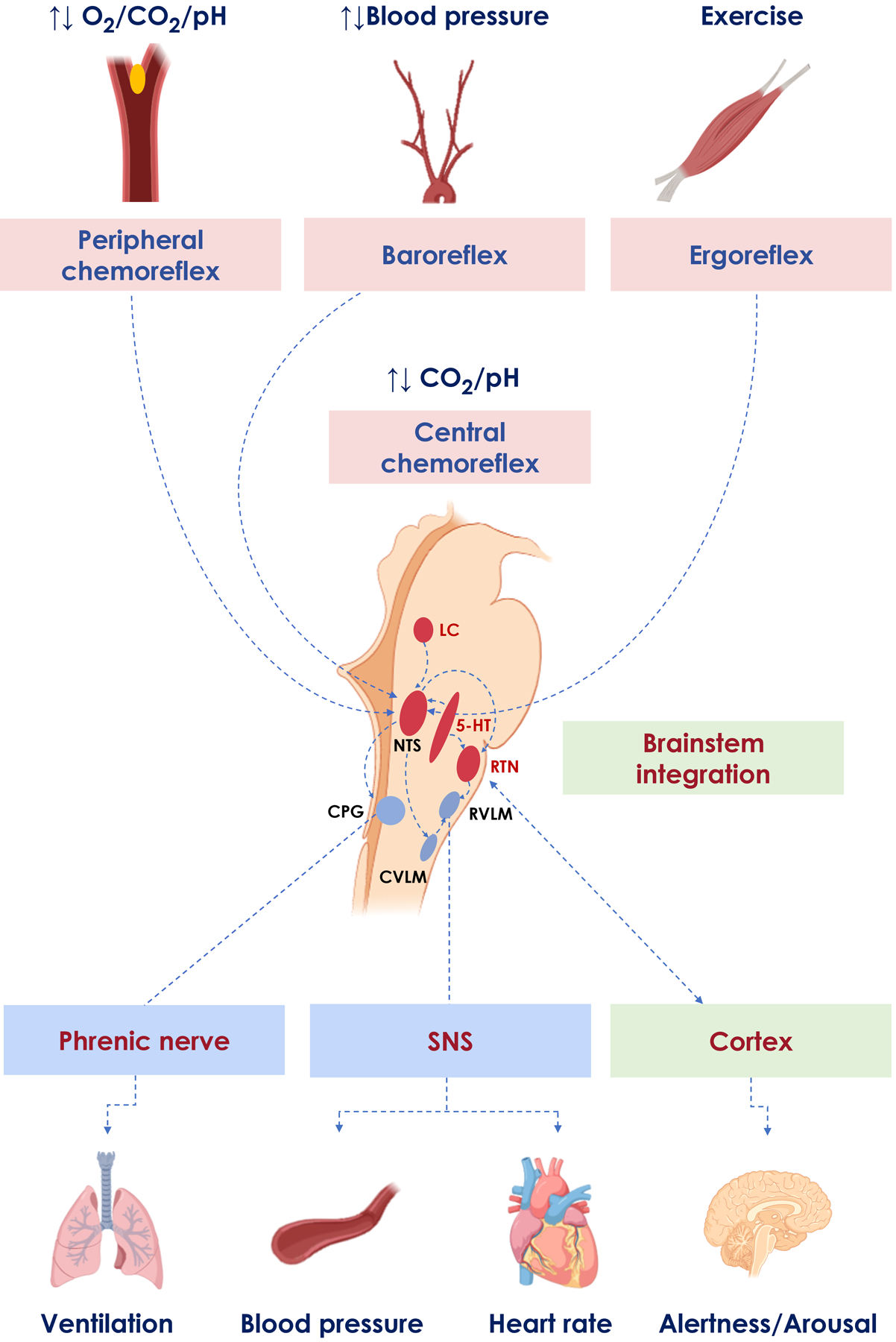

Figure 1. The integrated system of neuroreflexes.

The central chemoreflex (CR) network is a highly integrated system of neurons and glia. Afferents from peripheral CR, baroreceptors, and ergoreflex receptors reach the brainstem at the nucleus tracti solitari (NTS) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), where they interact with central CR signals. Together, all those systems regulate ventilation via the central pattern generator (CPG), blood pressure and heart rate via RVLM, and arousal/alertness responses through ascending cortical pathways.

5-HT: 5-hydroxytryptamine neurons (serotonergic); CVLM: caudal ventrolateral medulla; LC: locus coeruleus; SNS: sympathetic nervous system; RTN: retrotrapezoid nucleus.

Table 1.

Peripheral and central chemoreceptors

| Peripheral CR | Main neurotrasmitter | Main stimulus increasing firing | Location | Roles and relative contribution of gas response | Role in sleep/wake | Efferents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I cells1,9,10 | ATP adenosine dopamine acetylcholine | ↓ O2 ↓ pH / ↑ CO2 ↓ perfusion ↑ temperature ↑ catecholamines ↑ angiotensin II ↑ lactate ↑ potassium ↓ plasma glucose |

Carotid bodies Aortic bodies |

100% to O2 ~ 20–30% to CO2 |

Essential in sleep Important during wakefulness |

Carotid sinus branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve → NTS | |

| Type II cells1,9,10 | ATP | ↑ Purinergic stimulation of P2Y2 receptors | Carotid bodies Aortic bodies |

Paracrine sensitization or neural stem cell progenitor of type I cells | Unknown | Type I cells paracrine stimulation or nerve ending of the carotid sinus branch | |

| Central CR | Main neurotransmitter | Main stimulus increasing firing | Location | Roles and relative contribution of central CR to CO2 | Role in sleep/wake | Efferents | |

| Serotonergic1,12 | 5-HT | ↓ internal pH | Medullary and midbrain raphé | Physiological pH (7.2–7.4) ↓ ~ 50% |

Medullary: Wake, reduced firing during sleep Midbrain: Reduced threshold for REM sleep |

Medullary: Pre-BötC, RTN, NTS, phrenic nerve, XII motor nucleus Midbrain: thalamus, limbic system |

|

| RTN1,12 | Glutamate | ↑ CO2/ ↓ pH (↑ stimulation of H+ sensitive channels, TASK2 and GPR4) |

Ventral respiratory region, ventral to the VII nerve motor nucleus | Integration center Lower pH (7.0–7.5) Diurnal and nocturnal response ↓ Large proportion of response due to input from other chemoreceptors |

Tidal volume: Wake, NREM and REM sleep Respiratory rate: quiet wake and NREM sleep |

rVRC, cVRC, pre-BötC, BötC, NTS, Kölliker-Fuse nucleus | |

| Orexin1,12 | Orexin | ↑ CO2/ ↓ pH | Lateral hypothalamus Prefornical area Dorsomedial hypothalamus |

Mainly diurnal response Exercise response Arousal response ↓ 20–50% |

Wake only | Medullary raphe, RTN, preBötC, Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, NTS, RVLM, premotor neurons of phrenic and XII nerves, limbic system |

|

| Locus Coeruleus1,12 | Norepinephrine | ↓ internal pH | Floor of the IV ventricle | Mainly diurnal response Alert response to higher CO2 levels Integration center ↓ ~ 60% |

Wake |

Sleep/Arousal: Basal forebrain, preoptic regions Autonomic regulation: RVLM, IMLC, caudal raphé |

|

| Glia1,12 | ATP Adenosine |

↑ CO2/ ↓ pH (Na+-induced ↑Ca2+ → ATP release → RTN activation via P2 receptors) ↓O2 (TRPA1 channels) |

Diffuse but predominantly VRC | Amplification of central chemosensitivity to CO2 | - | Predominantly RTN | |

Abbreviations: 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; BötC, Bötzinger complex; CR: chemoreceptors; CO2, carbon dioxide; cVRC, ventral respiratory column; GPR4: guanine nucleotide–binding proteins receptors; IMLC, intermediolateral column; NREM: non-rapid eye movement; NT: neurotransmitter; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; preBötC, preBötzinger complex; O2, oxygen; REM: rapid eye movement; RTN, retrotrapezoid nucleus; RVLM, rostral ventrolateral medulla; rVRC, rostral ventral respiratory column; TASK2: TWIK-related acid-sensitive K+ channel; TRPA1: transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1.

Peripheral CR are sited in the carotid bodies (CB) and in the aortic bodies.8,9 CB are composed of chemoreceptor type I cells surrounded by glial type II cells. The type I cells are polymodal and respond to changes in arterial PO2, PCO2, pH, low perfusion, temperature, catecholamines, lactate, angiotensin II, potassium, and plasma glucose.10 They release multiple inhibitory or stimulatory neurotransmitters (ATP, adenosine, dopamine, and acetylcholine),2,11 as summarized in Table 1. Peripheral CR contribute up to 30% of ventilatory response to CO212 and are the main O2 sensors in the body,13–15 modulating also the autonomic outflow.1,2,6,16

Central CR are a complex, highly integrated, neuronal and glial network responsible for regulation of the ventilatory response to PCO2 (~70–80%)12 and arousal. Different groups of neurons have been proposed as central CR, operating with different CO2 thresholds at different times of the day, or under different conditions. Prominent subgroups of central CR include serotonergic, glutamatergic, adrenergic and orexinergic neurons, as well as purinergic receptors on glial cells, as summarized in Table 1. Central CR also regulate autonomic output.1,6 Peripheral and central CRs have different activating threshold for ventilation and adrenergic responses in healthy individuals,6 with potential sex related differences.17 Indeed, compared to men, women show an attenuated ventilatory response to both peripheral and central chemoreflex activation,17,18 while they show an augmented sympathethic response to central chemoreflex activation.17 CR stimulation of higher circuits (thalamus, limbic system) also activates arousal and attention/wake promoting pathways with potentially aversive reactions, such as dyspnoea or panic, secondarily affecting sympathetic discharge and ventilation.1

Peripheral and central CR are intertwined, with hypo-additive, additive, and hyper-additive responses in animals (depending on the species and experimental preparations used),19 and additive response in humans.19 CR are also tightly connected with baroreceptor and ergoreceptors (Figure 1). In animals, baroreflex activation inhibits while deactivation augments the peripheral CR ventilatory20 and vasoconstrictor responses.21 Once stimulated, the baroreflex seems to exert an inhibitory action on peripheral CR (hypoxia) in humans,22 while constant peripheral CR stimulation (high altitude hypoxia) was shown to cause baroreflex resetting rather than inhibition.23 Finally, CR and ergoreceptors are coordinated during exercise to match ventilation with increased metabolic CO2 production and O2 consumption.24 During mild exercise, peripheral chemosensitivity to O2/CO2 significantly increases in healthy subjects25 and this is secondary to increased sympathetic activity, exercise metabolites stimulating peripheral CR, and to the integration with ergoreceptors afferents at medullary level (Figure 1).26 In this context, the potentiation of CB activation by lactate during exercise may facilitate ventilatory compensation and blunt peripheral lactate release during exercise.27

3. Epidemiology of chemoreflex dysfunction

Enhanced chemosensitivity has been described in arterial hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).6,28–30 The evidence of heightened peripheral chemosensitivity to hypoxia in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR)31 was later confirmed in young humans with borderline28 or mild hypertension,29 showing an increased blood pressure response to hypoxia.28 In non-hypercapnic OSA, chronic intermittent hypoxia seems to promote peripheral CR sensitization over time,30,32 causing sympathetic overactivity during wakefulness via cingulate and thalamic regions,33 with potential effects also on central CR.

The critical role of increased chemosensitivity has also been extensively studied in subject with HF.34–36 In a population of 110 patients with systolic HF (mean left ventricular ejection fraction, LVEF 31±7%), an increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia, to hypercapnia or both was observed in 12%, 21% and 28%, respectively.34 Similar prevalence rates were observed in HF by Ponikowski35 and Niewinski,37 who found an increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia in 40–45% of patients, and Javaheri36, who found an increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia in 30% of patients, respectively.

The epidemiology of chemoreflex activation in patients with coronary artery disease is unclear and may partly depend on the treatment, since ticagrelor has been associated with chemoreflex sensitization and central apnoeas (CA) in this setting.38,39 In ischemic cerebral disease, increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia has been described in patients with bilateral stroke presenting with CA,40 and may be epidemiologically relevant considering a prevalence of CA of 12% in this context.41

On the other hand, a decreased chemosensitivity has been described in obesity hypoventilation syndrome, the Pickwickian syndrome (hypercapnic OSA), and some neurological conditions, such as congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.42,43 In hypercapnic OSA, both hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses are diminished.44

4. Pathophysiology of chemoreflex dysfunction

4.1. Arterial hypertension

Increased chemosensitivity is involved in neurogenic and OSA-related hypertension (Table 2 and Graphical Abstract).30–32,45,46

Table 2.

Hyperactive chemoreflex: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment in heart failure and hypertension

| Clinical scenario | Epidemiology | Pathophysiological background | Common signs and symptoms and prognosis | Available treatment options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT (neurogenic) (OSA) |

- | Peripheral CR

|

Clinical picture

|

Peripheral CR |

| HF (systolic) |

50 subjects with systolic HF35

|

Pepipheral CR

|

Clinical picture

|

Peripheral CR

|

Abbreviations: 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; 8-OH-DPAT: 8-Hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin; ASIC: acid-sensing ion channel; ATII: angiotensin II; CA: central apneas; CB: carotid bodies; CR: chemoreceptors; CI: confidence interval; HCSB: Cheyne/Stokes respiration; HCVR: hypercapnic ventilatory response; HF: heart failure; HR: hazard ratio; HT: hypertension; HVR: hypoxic ventilatory response; LA: left atrial; O2: oxygen; OR: orexin; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea; PAG: DL-Propargylglycine cystathionine γ-lyase inhibitor; P2XR: purinergic receptor 2X; CR: chemoreceptor; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SNS: sympathetic nervous system; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TASK: two-pore-domain potassium channel; TCA: tricyclic antidepressants.

Activation of the sympathetic and renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) seem the primary mechanism,45,46 while CB chronic hypoperfusion secondary to atherosclerotic processes, and chronic hypoxia/reoxygenation, may play a supplemental role in some phenotypes (i.e., OSA).45,46 CB hypertrophy and a higher expression of both ASIC and TASK channels, which are responsible for type I cells’ response to pH changes, have also been described.47 Finally, increased levels of adenosine have been observed in chronic intermittent hypoxia, as in OSA, increasing peripheral chemosensitivity.48

In the long term, persistently increased sympathetic activity – secondary to intermittent hypoxia, stimulation of peripheral CR along with baroreceptor resetting – could promote vascular remodeling and persistent elevation of blood pressure during sleep, but also during wakefulness,49 even though other mechanisms may be important as well (i.e., OSA-related arousals or dysbiosis).50,51

A potential role of central CR must be considered too, especially of the orexin system, which is upregulated in SHR, with increased chemosensitivity to hypercapnia even after hyperoxic blunting of peripheral CR.45,46 Furthermore, an association between OSA and genetic variants of glial-derived growth factor and the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A-receptor (5-HT2A) has been identified in a large cohort of European and African-American subjects.52

4.2. Heart failure

In HF, both peripheral and central CR are frequently overactive (Table 2 and Graphical Abstract).

Chronic CB hypoperfusion, alternating hypoxia/reoxygenation cycles and reduced shear stress induce local production of reactive oxygen species,53 while persistent activation of sympathetic and RAAS upregulates pro-oxidant and downregulates antioxidant systems, impairing potassium/calcium signaling and cellular excitation.54,55 Angiotensin II also promotes the secretion of ATP from type II CB cells, causing purinergic postsynaptic sensitization. However, angiotensin receptor antagonists do not appear to impact significantly on peripheral chemosensitivity.55,56 Chronic hypoxia/reoxygenation also upregulates the endothelin system, with subsequent vasoconstriction further reducing CB perfusion.54 Finally, HF patients also exhibit higher plasma levels of adenosine, which can augment peripheral chemosensitivity to O2, promoting CA and reflexively increasing efferent muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA).55,57,58

The molecular mechanisms of increased central chemosensitivity in HF are less defined. First, tonic stimulation from peripheral to central CR has been hypothesized.59 A role of increased sympathetic drive and RAAS activation has also been postulated, as alpha-2 agonists reduce central chemosensitivity and angiotensin I receptors were identified in the rostral ventrolateral medulla.60,61 Finally, increased left atrial pressure and pulmonary J receptor stimulation may favor central CR sensitization through brainstem integration.62 Indeed, the prevalence of CA increases with sign of elevated atrial pressure in HF, across the whole spectrum of LVEF.49

5. Diagnostic assessment of the chemoreflex

There are several ways to assess the chemoreflex in humans, but they all consider the O2 and CO2 contributions to ventilatory changes separately.63 Chemoreflex function may be assessed both in terms of sensitivity (i.e., response to gas challenges) or tonic activity (for peripheral CRs).

As for chemoreflex sensitivity, the first test developed were based on steady state methods.64 Steady-state tests consisted of maintaining inspired fractional concentrations of O2 and CO2 for many minutes (5–20) to allow for equilibration in all tissues.

To overcome variation in cerebral blood flow due to prolonged hypoxia/hypercapnia, transient tests were developed. To study peripheral chemosensitivity to CO2, a single breath of CO2 (13%) is given and ventilatory response determined within the first 20 seconds,65 to exclude the slower responding central CR. The peripheral chemosensitivity to O2 is commonly evaluated after two to eight breaths of pure nitrogen, causing a fast drop in O2 saturation (SaO2) and a rise in ventilation in about 10 seconds.66,67

Another way to assess the chemoreflex sensitivity is to use the rebreathing techniques.68,69 In the rebreathing test for O2 sensitivity, the subject breathes in a closed circuit so that as PO2 decreases ventilation rises, accordingly; PCO2 is kept constant through a scrubbing circuit.70 To assess chemosensitivity to hypercapnia, normoxia is maintained by adding O2 to the circuit.34,71 The slope of the regression line between SaO2 and ventilation or between CO2 and ventilation is a measure of chemosensitivity to hypoxia or hypercapnia, respectively. If the test is performed in hyperoxic conditions, as in the standard Read`s rebreathing technique (5% CO2 + 95% O2), central chemosensitivity is assessed (blunting peripheral CRs):63 the addition of CO2 in the rebreathing bag is done to increase PaCO2 and etCO2 rapidly up to the mixed venous PCO2. Peripheral chemosensitivity can be then estimated by subtraction, starting this time from a normoxic or hypoxic hypercapnic test, for both ventilatory and noradrenergic responses (Figure 2).8 If hyperventilation is performed before the rebreathing, as developed by Duffin, the CR recruitment threshold to CO2 may be identified.72

Figure 2. Rebreathing test.

Hypoxic hypercapnic (filled circles) and hyperoxic hypercapnic (open circles) rebreathing tests displayed plotting end tidal carbon dioxide (PETCO2) as a function of ventilation (A) or muscle sympathetic nervous activity (MSNA) in a healthy volunteer. Big circles refer to bin-averaged values (from different subjects) of ventilation (left panel) and MSNA (right panel) for 2 mmHg intervals of PETCO2 variation. Whiskers refer to the standard deviation of PETCO2 (horizontal whiskers), and either ventilation or MSNA (vertical whiskers). Fitted double linear models are superimposed over the data (hyperoxia, black and hypoxia, grey). Gently taken and adapted (with permission) from Keir et al.13

On the other hand, the tonic activity of peripheral CRs has been shown to contribute to both resting ventilation and hemodynamic control in humans, by interacting with baroreflex function.73–75 Notably, such contributions may be easily estimated by inhibiting peripheral CR, through either hyperoxia or low-dose dopamine infusion, and assessing the subsequent changes in minute ventilation, heart rate, and blood pressure.73–75

6. Clinical significance of chemoreflex dysfunction

6.1. Hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea

Potentiated chemoreflex-mediated sympathetic vasoconstriction has been documented in patients with neurogenic hypertension, especially in patients with OSA,76 and it is reversed by hyperoxia, which blunts peripheral CR.77 In the so-called high loop-gain OSA and mixed apnoeas, enhanced chemoreflex may also cause ventilatory overshoot after apnoea, with hypocapnia causing hypotonia of the upper airway musculature78,79 and subsequent hypopnea and/or apnoea, by lowering PaCO2 towards or below apneic threshold.

OSA have been associated both with brady- and tachyarrhythmias, especially during sleep, and a role for CR has been suggested for both phenomena.80 While CR stimulation in the absence of ventilation (late apnoea) may cause vagal reflex inhibition of the heart favoring sinus arrest or atrioventricular blocks,80,81 OSA-induced CR oversensitization during normal breathing may promote ectopics, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular arrhythmic events, also during wakefulness.80,81

6.2. Heart failure

In HF, increased chemoreflex sensitivity, alongside increased plant gain (i.e., increased changes in PCO2 for a given change in ventilation) and prolonged lung-to-chemoreceptor circulation time promote ventilatory instability, as hypothesized by mathematical models,82 and confirmed in both animal54,55,59 and human studies.34–36 Indeed, patients with HF often exhibit a respiratory pattern characterized by alternating phases of hyperventilation and CA, named Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes breathing (HCSB).34–36

Notably, these 3 mechanisms are state independent (i.e., present while awake and asleep), and consequently CA/HCSB could be observed during wakefulness at rest and exercise.83,84 Nevertheless, CA/HCSB is usually most pronounced during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, due to predominance of the chemical control of breathing and the unmasking of the apneic threshold.85 Increased arterial circulation time may prolong CA/HCSB cycle, especially in patients with reduced LVEF, as a result of delayed transfer of information regarding the level of gas tensions in the pulmonary capillary bed to chemoreceptors.58,86–89

Increased chemosensitivity has been associated with more severe dyspnoea, as expressed by a higher NYHA class, in HF patients.25 Indeed, CR firing increases the respiratory motor output that can be consciously felt as unpleasant, and signals with ascending connections to areas of the limbic system and cortex involved with the perception of dyspnoea,90 being together with CB lactate sensing27 and increased ergoreflex sensitivity during effort a main determinant of HF symptoms.

HF patients with elevated chemosensitivity also present exercise limitation with lower peak O2 consumption and ventilatory efficiency (increased VE/VCO2 slope),25,34,91 which correlate with CA severity in HF.92 Notably, chemoreflex downregulation with hyperoxia,93 or dihydrocodeine administration94 improves exercise tolerance, ventilatory efficiency, and dyspnoea in HF patients. No study has yet investigated the relationship between overactive CR and exertional oscillatory ventilation, another ominous prognostic marker in HF, so far mainly related to the haemodynamic compromise during exercise.95

Furthermore, patients with overactive CR show signs of sympathovagal imbalance with sympathetic predominance, and a higher risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.34,35,96–98 In animal models, peripheral CR overactivity has been linked with increased sympathetic drive to the heart,99 leading to adverse remodeling and proarrhythmic events, and to the kidneys,100 causing reduced renal blood flow and predisposing to cardiorenal syndrome. Chemoreflex has also been linked to pulmonary vasoconstriction during CA and right ventricular overload in HF patients.101,102 In this respect, microneurographic tecniques may further clarify the relationship between chemoreflex overactivation and sympathovagal imbalance in HF.8,103

Moreover, increased chemosensitivity carries itself a poor prognosis in HF. In patients with systolic HF (n=80, LVEF <45%), recruited in the pre-beta-blocker era, increased peripheral chemosensitivity to hypoxia (cutpoint: >0.72 L/min/%SaO2, transient hypoxic test) was shown to be an independent predictor of overall death at multivariable analysis.104

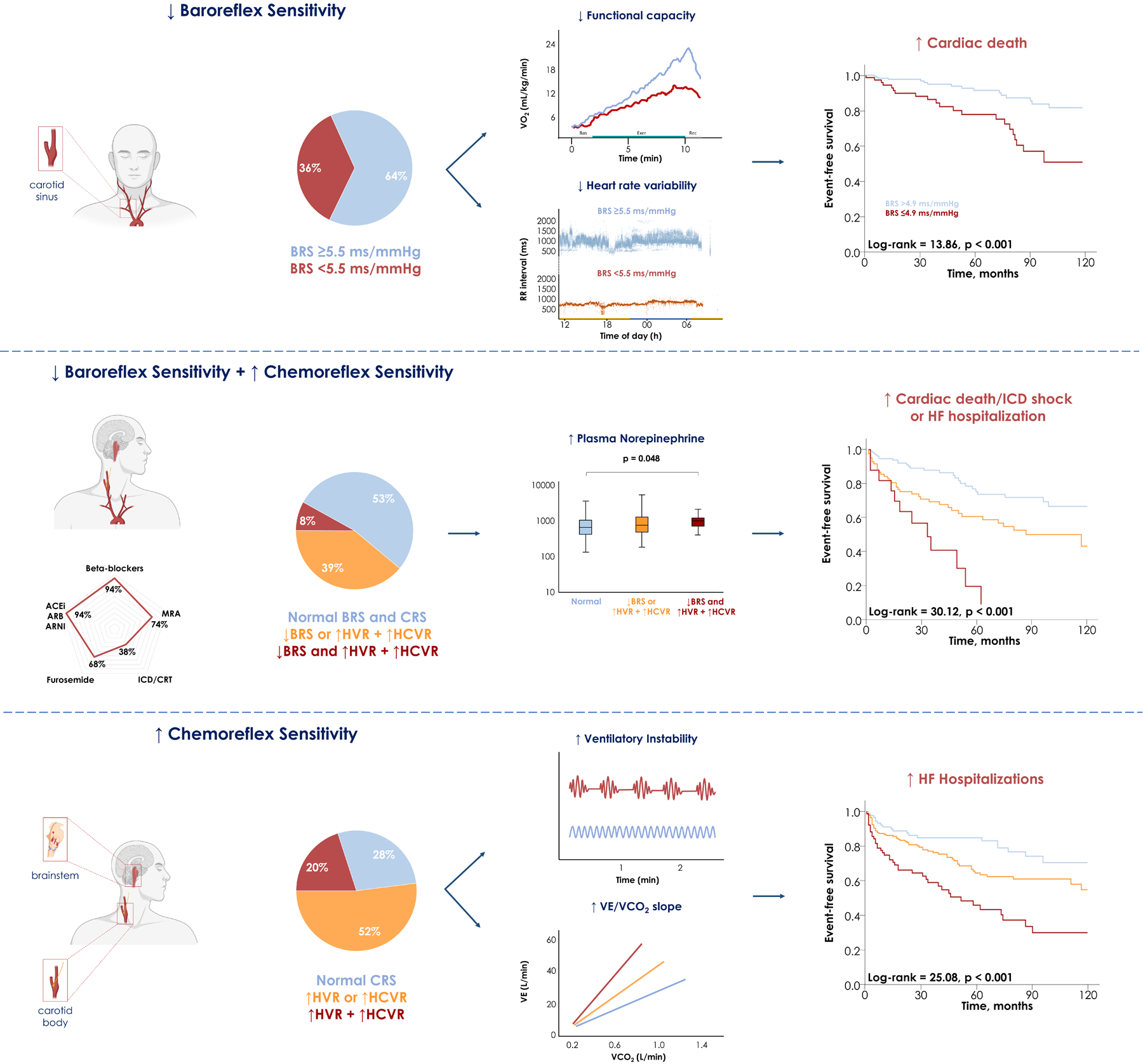

These results were later replicated by Giannoni et al. in two different studies on HF patients.34,105 In the largest study conducted so far (n=425) in patients with HF (LVEF <50%) on modern treatment, a combined increased chemosensitivity to hypoxia and hypercapnia was found to be an independent predictor of the primary outcome (a composite of cardiac death, appropriate implantable defibrillator shocks and HF hospitalization) and the secondary outcomes (i.e., each individual component of the primary outcome). A particulary detrimental outcome was observed in patients with both increased chemosensitivity and decreased baroreflex sensitivity (Figure 3). Notably, adding chemoreflex and baroreflex sensitivity to a multivariate prognostic model (including age, aetiology, LVEF, NT-proBNP, renal function, peak O2 consumption, and VE/VCO2 slope) significantly improved risk prediction.105

Figure 3. Abnormal baroreflex (BRS) and chemoreflex sensitivities (CRS) in patients with chronic heart failure (HF).

Abnormal BRS and CRS may be frequently observed in chronic HF patients on modern therapies and both contribute to autonomic dysfunction. Abormal BRS is also associated with functional impairment and a significantly higher risk of cardiac death, while abnormal CRS (particularly when both the hypoxic [HVR] and the hypercapnic ventilatory responses [HCVR] are heightened) is associated with ventilatory instability and higher risk of HF hospitalization. When both reflexes are abnormal, the risk of adverse events is very high, with less than 10% of patients being free of events over a 60-month follow-up. Taken and adapted with permission from Giannoni A et al.92

7. Therapeutic approaches to chemoreflex dysfunction

Considering its clinical significance, chemoreflex has been recently proposed as a potential therapeutic target (Figure 4).5 The optimal criteria to select the patients who could benefit more from CR modulation is still a matter of debate. While CR sensitivity, assessed through ventilatory response, has been extensively associated with poor outcomes,31,62,101 the study of CR tonicity may also predict clinical response to treatment.106 Furthermore, the possible role of either clinical or biohumoral markers as surrogates of CR function (not routinely assessed) to select patients for chemoreflex modulation remains to be clarified.107

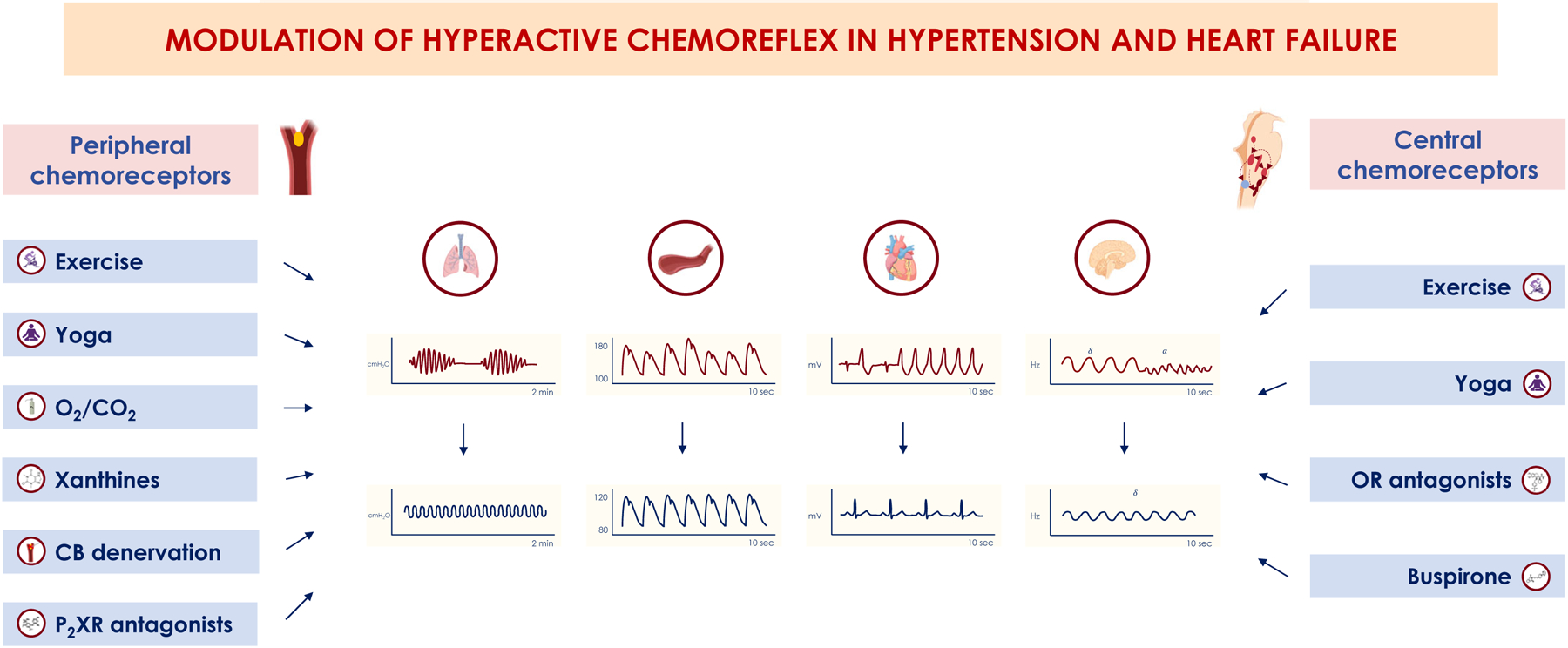

Figure 4. Potential treatments of chemoreflex hyperactivation in heart failure and hypertension.

In hypertension, surgical denervation of carotid bodies or their silencing with oxygen (O2) has also been proposed to treat hyperactive peripheral chemoreceptors (CR), together with pharmacological modulation of the purinergic signaling with the novel P2X receptor (P2XR) antagonists. Similarly, pharmacological treatment of hyperactive central CR has also been tested with orexinergic receptor (OR) antagonists (almorexant and suvorexant) in neurogenic hypertension and high loop-gain obstructive apnoeas. In heart failure, modulation of carotid bodies with O2 and CO2 (especially given dynamically during CO2 drops following hyperventilation), with caffeine or theophylline acting on the adenosine pathway, or with surgical denervation have been attempted to target hyperactive peripheral CR. Central CR modulation has also been attempted, both with exercise training and yoga and with pharmacological agents as buspirone, by decreasing the serotonergic firing.

Chemoreflex modulation has been attempted in hypertension, mainly in preclinical models. In SHR, bilateral, but not unilateral, CB denervation increased baroreflex sensitivity (+32%) and decreased renal sympathetic nerve activity (−56%), low frequency component of heart rate variability (−28%) and arterial pressure by 17 mmHg (−12%).108 In a following safety and feasibility trial in humans, unilateral CB denervation was effective only in those with increased chemosensitivity (53% of the total population), though some feedback resetting occurred over time.109

A promising alternative is the pharmacological modulation of chemoreflex. SHR overexpress purinergic P2X3 receptors and show increased peripheral chemosensitivity,110 which was decreased by either the local or systemic delivery of two P2X3 receptor antagonists, AF-533 and AF-219, blunting adrenergic outflow and blood pressure.110 Although the possibility of modulating central CR has been tested in mice with neurogenic hypertension with promising results with an orexin antagonist, almorexant,111 its use was discontinued for safety concerns in humans. Suvorexant showed instead neutral results in patients with OSA.112

The subgroup of patients with HF/hypertension and OSA seems the most complex to manage,113 since chemosensitivity may be either increased (high loop-gain) or decreased (low loop-gain). Indeed, downregulating peripheral CR with O2 decreased the apnoea burden by 53% in the former group, but only by 4% in latter. On the contrary, stimulation of noradrenergic and serotonergic CR with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, was partly effective in low loop-gain OSA during NREM but not during REM sleep.113 In hypercapnic OSA progesterone administration has been also proposed.114,115

In HF, the possibility to modulate the hyperactive CR is particularly appealing in light of the prognostic role of chemoreflex in this setting.34,104 The phenotypic therapy of both OSA and CA in HF has been extensively reviewed elsewhere.116

Beta-blockers reduced peripheral chemosensitivity to hypoxia (carvedilol and nebivolol) and the central chemosensitivity to hypercapnia (carvedilol),117 with positive effect on ventilatory efficiency during exercise.118 RAAS antagonists were shown to normalize both sympathetic and ventilatory response to hypoxia in HF rabbits.119 Finally, cardiac resynchronization therapy reduced chemosensitivity to hypercapnia (by around 22%) 4–6 months after implantation.120 Left-ventricular-assist devices, on the other hand, only improved ventilatory efficiency during exercise with increased pump speed.121,122 Finally, heart transplant recipients showed a persistently higher peripheral ventilatory and sympathetic response to hypoxia, but not to hyperoxic hypercapnia, 7±1 years after surgery compared to controls.123

Approaches acting on ventilation rather than on respiratory gases, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)124 and phrenic nerve stimulation,125 may favorably decrease both oscillations in respiratory gases and, secondarily, chemoreflex stimulation.126 While CPAP was shown to decrease the chemoreflex sensitivity to hypoxia but not to hypercapnia in patients with OSA at least in the short term,126,127 the effects of CPAP and phrenic nerve stimulation on chemosensitivity in patients with HF and CA are still unknown. On the other hand, acetazolamide, a drug that reduces CA in HF likely by decreasing plant gain,116 also blunts the peripheral chemosensitivity to hypoxia, while increasing both chemosensitivity to hypercapnia and VE/VCO2 slope during exercise.128

CO2 enriched gas (4%) was able to abolish CA/HCSB in HF patients,129 even though it was later demonstrated that CO2 also promotes CR stimulation with sleep disruption and sympathetic overactivity,130 unless delivered by automatic approaches minimizing the dosage.131 On the other hand, a constant O2 flow (1–5 L/min) reduced peripheral CR activity and also nighttime CA by ~50%, improving exercise performance and decreasing sympathetic overactivity.130 A phase 3 randomized clinical trial (LOFT-HF, NCT03745898) on the prognostic effects of nocturnal O2 therapy in patients with stable HF and CA was eary terminated for delayed site activation and low recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In animal models of HF obtained by pacing overdrive (rabbit) or coronary artery ligation (rats), bilateral CB denervation stabilized breathing, reduced sympathetic outflow to the heart and kidney and restored baroreflex sensitivity.132,133 This translated into decreased risk of arrhythmias, positive reverse left ventricular remodeling, and improved survival.133 A similar approach was attempted in 10 HF patients with increased peripheral chemosensitivity.134 CB surgical resection was performed by a lateral approach to the carotid bifurcation, with CB macroscopically identified and histologically confirmed. After unilateral (n=4) or bilateral (n=6) CB denervation, peripheral chemosensitivity decreased by 70%, mainly in patients with bilateral resection. This led to a decrease in sympathetic activity, VE/VCO2 slope and increased exercise duration, with no changes in natriuretic peptides, LVEF, or quality of life indexes. However, decreased SaO2 at night was observed in 60% of patients, with one case of worsening OSA needing ventilatory support and two deaths during follow-up.134 A unilateral approach or, alternatively, a reversible pharmacological CB modulation may hence be preferred, considering the key role of CB in hypoxia sensing.135 In this setting, intra-carotid injection of adenosine has been proposed to assess the residual chemoreflex function after carotid body ablation.136 From a single study run in 6 male CHF patients, it seems that after CB denervation ventilatory and blood pressure responses to hypoxia are strongly reduced, while heart rate response (tachycardia) is preserved, suggesting a potential role for other hypoxia sensors as aortic bodies also in humans.137

Some drugs potentially acting on peripheral CR have been also tested. Caffeine, an adenosine receptor antagonist, decreased MSNA response to handgrip maneuver in HF138 and peripheral CR activity in an animal models,139 while theophylline, another adenosine antagonist, halved CA and improved SaO2 in HF patients,140 even though this effect might primarly be driven by a reduction in the plant gain,141 similarly to acetazolamide.116

Furthermore, a hydrogen sulfide inhibitor, DL-Propargylglycine cystathionine γ-lyase inhibitor, was shown to decrease the peripheral chemosensitivity stabilizing breathing and ameliorating autonomic indexes in a rat model of HF.142 Finally, in an animal model of post-infarction HF, simvastatin treatment significantly improved respiratory variability through the upregulation of Krüppel-like factor 2 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase, whose reduced expression within the CB and the nucleus tracti solitari is associated with enhanced chemosensitivity143,144.

Another interesting possibility is to target the central CR. In particular, the serotonergic system seems a promising target, since it contributes to 30–50% of the chemosensitivity to hypercapnia in the physiological range and can be modulated by well-characterized medications. Buspirone, a presynaptic 5-HT1A receptor agonist long and safely used in general anxiety disorder, was shown to decrease the chemosensitivity to hypercapnia and stabilize breathing in a mouse model of hypoxia-induced apnoeas.142,145 Similar results were obtained with another 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin, in rats and piglets.146,147 A recent double-blind randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial, the BREATH study,148 has investigated the effect of oral buspirone administration (45 mg) in patients with systolic HF (n=16). After 1-week of treatment, buspirone decreased central chemosensitivity to hypercapnia and reduced CA throughout the 24-hour period compared to placebo, without significant side effects.

Lastly, modulation of respiration using slow breathing as in yoga,149 exercise physical training,150 or baroreflex stimulation151,152 may be successful strategies in decreasing chemosensitivity in HF and hypertension by acting on brainstem integration circuits.

8. Conclusions

The chemoreflex is a closed loop reflex, tightly integrated with baroreflex and ergoreflex, that matches ventilation and sympathetic drive with blood gases. Its dysfunction contributes to highly prevalent pathologies such as hypertension and HF.

A deeper understanding of the pathophysiological basis of chemoreflex hyper- or hypoactivity, coupled with the recent insight into respiratory and sympathetic chemoreflex responses, has led to the development of interesting new therapeutic approaches both in hypertension and HF, opening an exciting new research field and prompting the design of larger and longer clinical studies with particular relevance towards the selection of patients that would benefit the most from chemoreflex modulation strategies.

Table 3.

Hypoactive chemoreflex: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.

| Hypoactive Chemoreflex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical scenario | Epidemiology | Pathophysiological background | Common signs and symptoms | Available treatment options |

| CCHS | - | Peripheral CR

|

|

Central CR

|

| SUDEP | - | Peripheral CR - Central CR

|

|

Central CR |

Abbreviations: H2S: hydrogen sulfide; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; CR: central chemoreceptors; CCHS: congenital central hypoventilation syndrome; O2: oxygen; PCR: peripheral chemoreceptor; PAG: Phox2b: paired-like homeobox 2b; RTN: retrotrapezoid nucleus; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; TH: tryptophan hydroxylase.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health (grant number U01 NS090414) and by the Canadian Institutes of Health (research project grant number PJT 159491).

List of abbreviations

- CA

central apnoeas

- CB

carotid bodies

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- CR

chemoreceptors

- HCSB

Hunter-Cheyne-Stokes Breathing

- HF

heart failure

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MSNA

muscle sympathetic nerve activity

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnoeas

- RAAS

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- REM

rapid eye movement

- SaO2

oxygen saturation

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rats

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Guyenet PG. Regulation of breathing and autonomic outflows by chemoreceptors. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1511–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javaheri S Determinants of Carbon Dioxide Tension. In: Gennari FJ, Adrogue HJ, Gall JH, Madias NE, eds. Acid-Base Disorders and Their Treatment 1st ed. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis; 2006. p. 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toledo C, Andrade DC, Lucero C, Schultz HD, Marcus N, Retamal M, Madrid C, Del Rio R. Contribution of peripheral and central chemoreceptors to sympatho-excitation in heart failure. J Physiol. 2017;595:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sainju RK, Dragon DN, Winnike HB, Nashelsky MB, Granner MA, Gehlbach BK, Richerson GB. Ventilatory response to CO 2 in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2019;60:508–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannoni A, Mirizzi G, Aimo A, Emdin M, Passino C. Peripheral reflex feedbacks in chronic heart failure: Is it time for a direct treatment? World J Cardiol. 2015;7:824–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iturriaga R Carotid Body Ablation: a New Target to Address Central Autonomic Dysfunction. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nabbout R, Mistry A, Zuberi S, Villeneuve N, Gil-Nagel A, Sanchez-Carpintero R, et al. Fenfluramine for Treatment-Resistant Seizures in Patients With Dravet Syndrome Receiving Stiripentol-Inclusive Regimens: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:300–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zera T, Moraes DJA, Silva MP Da, Fisher JP, Paton JFR. The Logic of Carotid Body Connectivity to the Brain. Physiology (Bethesda). 2019;34:264–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heymans C, Bouckaert J. Sinus caroticus and respiratory reflexes: I. Cerebral blood flow and respiration. Adrenaline apnoea. J Physiol. 1930;69:254–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar P, Bin-Jaliah I. Adequate stimuli of the carotid body: more than an oxygen sensor? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;157:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lugliani R, Whipp BJ, Seard C, Wasserman K. Effect of bilateral carotid-body resection on ventilatory control at rest and during exercise in man. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelman NH, Epstein PE, Lahiri S, Cherniack NS. Ventilatory responses to transient hypoxia and hypercapnia in man. Respir Physiol. 1973;17:302–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez C, Almaraz L, Obeso A, Rigual R. Carotid body chemoreceptors: from natural stimuli to sensory discharges. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:829–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blain GM, Smith CA, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Contribution of the carotid body chemoreceptors to eupneic ventilation in the intact, unanesthetized dog. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;106:1564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodges MR, HV Forster HV. Respiratory neuroplasticity following carotid body denervation: Central and peripheral adaptations. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:1073–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keir D, Duffin J, Millar P, Floras J. Simultaneous assessment of central and peripheral chemoreflex regulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity and ventilation in healthy young men. J Physiol. 2019;597:3281–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayegh ALC, Fan JL, Vianna LC, Dawes M, Paton JFR, Fisher JP. Sex differences in the sympathetic neurocirculatory responses to chemoreflex activation. J Physiol. 2022;600:2669–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentile F, Borrelli C, Sciarrone P, Buoncristiani F, Spiesshoefer J, Bramanti F, et al. Central Apneas Are More Detrimental in Female Than in Male Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e024103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Z, Fisher JA, Duffin J. Central-peripheral respiratory chemoreflex interaction in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;180:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heistad D, Abboud FM, Mark AL, Schmid PG. Effect of baroreceptor activity on ventilatory response to chemoreceptor stimulation. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mancia G Influence of carotid baroreceptors on vascular responses to carotid chemoreceptor stimulation in the dog. Circ Res. 1975;36:270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Somers VK, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Interaction of baroreceptor and chemoreceptor reflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1953–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halliwill JR, Morgan BJ, Charkoudian N. Peripheral chemoreflex and baroreflex interactions in cardiovascular regulation in humans. J Physiol. 2003;552:295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt H, Francis DP, Rauchhaus M, Werdan K, Piepoli MF. Chemo- and ergoreflexes in health, disease and ageing. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98:369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua TP, Ponikowski P, Harrington D, Anker SD, Webb-Peploe K, Clark AL, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lykidis CK, Kumar P, Balanos GM. The respiratory responses to the combined activation of the muscle metaboreflex and the ventilatory chemoreflex. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;648:281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres-Torrelo H, Ortega-Sáenz P, Gao L, López-Barneo J. Lactate sensing mechanisms in arterial chemoreceptor cells. Nat Commun; 2021;12:4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trzebski A, Tafil M, Zoltowski M, Przybylski J. Increased sensitivity of the arterial chemoreceptor drive in young men with mild hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 1982;16:163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siński M, Lewandowski J, Przybylski J, Bidiuk J, Abramczyk P, Ciarka A, et al. Tonic activity of carotid body chemoreceptors contributes to the increased sympathetic drive in essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:487–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floras JS. Hypertension and Sleep Apnea. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:889–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda Y, Sato A, Trzebski A. Carotid chemoreceptor discharge responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1987;19:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Rio R, Moya EA, Iturriaga R. Carotid body and cardiorespiratory alterations in intermittent hypoxia: the oxidative link. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor KS, Millar PJ, Murai H, Haruki N, Kimmerly DS, Bradley TD, et al. Cortical autonomic network gray matter and sympathetic nerve activity in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2018;41:zsx208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannoni A, Emdin M, Bramanti F, Iudice G, Francis DP, Barsotti A, et al. Combined Increased Chemosensitivity to Hypoxia and Hypercapnia as a Prognosticator in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1975–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chua TP, Ponikowski P, Webb-Peploe K, Harrington D, Anker SD, Piepoli M, et al. Clinical characteristics of chronic heart failure patients with an augmented peripheral chemoreflex. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Javaheri S A Mechanism of Central Sleep Apnea in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:949–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niewinski P, Engelman ZJ, Fudim M, Tubek S, Paleczny B, Jankowska EA, et al. Clinical predictors and hemodynamic consequences of elevated peripheral chemosensitivity in optimally treated men with chronic systolic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19:408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannoni A, Emdin M, Passino C. Cheyne–Stokes Respiration, Chemoreflex, and Ticagrelor-Related Dyspnea. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1004–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giannoni A, Borrelli C, Gentile F, Mirizzi G, Coceani M, Paradossi U, et al. Central apnoeas and ticagrelor-related dyspnoea in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Hear J - Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7:180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plum F, Brown HW. Neurogenic factors in periodic breathing. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1961;86:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seiler A, Camilo M, Korostovtseva L, Haynes AG, Brill A-K, Horvath T, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing after stroke and TIA: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2019;92:e648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paton JY, Swaminathan S, Sargent CW, Keens TG. Hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses in awake children with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:368–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin Z, Chen ML, Keens TG, Ward SLD, Khoo MCK. Noninvasive assessment of cardiovascular autonomic control in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2004;2004:3870–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Javaheri S, Colangelo G, Lacey W, Gartside PS. Chronic hypercapnia in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Sleep. 1994;17:416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li A, Roy SH, Nattie EE. An augmented CO2 chemoreflex and overactive orexin system are linked with hypertension in young and adult spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol. 2016;594:4967–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Holloway BB, Souza GMPR, Abbott SBG. Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla and Hypertension. Hypertension 2018;72:559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan Z-Y, Lu Y, Whiteis CA, Simms AE, Paton JFR, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Chemoreceptor hypersensitivity, sympathetic excitation, and overexpression of ASIC and TASK channels before the onset of hypertension in SHR. Circ Res. 2010;106:536–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conde SV, Monteiro EC, Sacramento JF. Purines and Carotid Body: New Roles in Pathological Conditions. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, Dempsey JA, Khayat R, Javaheri S, et al. Sleep Apnea: Types, Mechanisms, and Clinical Cardiovascular Consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:841–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Javaheri S, Gay PC. To Die, to Sleep - to Sleep, Perchance to Dream…Without Hypertension: Dreams of the Visionary Christian Guilleminault Revisited. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15:1189–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farré N, Farré R, Gozal D. Sleep Apnea Morbidity: A Consequence of Microbial-Immune Cross-Talk? Chest. 2018;154:754–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larkin EK, Patel SR, Goodloe RJ, Li Y, Zhu X, Gray-McGuire C, et al. A candidate gene study of obstructive sleep apnea in European Americans and African Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:947–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marcus NJ, Del Rio R, Ding Y, Schultz HD. KLF2 mediates enhanced chemoreflex sensitivity, disordered breathing and autonomic dysregulation in heart failure. J Physiol. 2018;596:3171–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schultz HD, Marcus NJ, Del Rio R. Role of the Carotid Body Chemoreflex in the Pathophysiology of Heart Failure: A Perspective from Animal Studies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;860:167–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schultz HD, Li YL, Ding Y. Arterial chemoreceptors and sympathetic nerve activity: implications for hypertension and heart failure. Hypertension. 2007;50:6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown CV, Boulet LM, Vermeulen TD, Sands SA, Wilson RJA, Ayas NT, et al. Angiotensin II-Type I Receptor Antagonism Does Not Influence the Chemoreceptor Reflex or Hypoxia-Induced Central Sleep Apnea in Men. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rongen GA, Senn BL, Ando S, Notarius CF, Stone JA, Floras JS. Comparison of hemodynamic and sympathoneural responses to adenosine and lower body negative pressure in man. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:128–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, Corbett WS, Nishiyama H, Wexler L, wt al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97:2154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dempsey JA, Smith CA, Blain GM, Xie A, Gong Y, Teodorescu M. Role of central/peripheral chemoreceptors and their interdependence in the pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;758:343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamada K, Asanoi H, Ueno H, Joho S, Takagawa J, Kameyama T, et al. Role of central sympathoexcitation in enhanced hypercapnic chemosensitivity in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2004;148:964–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ding Y, Li Y-L, Zimmerman MC, Schultz HD. Elevated mitochondrial superoxide contributes to enhanced chemoreflex in heart failure rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chenuel BJ, Smith CA, Skatrud JB, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Increased propensity for apnea in response to acute elevations in left atrial pressure during sleep in the dog. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duffin J The chemoreflex control of breathing and its measurement. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:933–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duffin J Measuring the respiratory chemoreflexes in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McClean PA, Phillipson EA, Martinez D, Zamel N. Single breath of CO2 as a clinical test of the peripheral chemoreflex. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ponikowski P, Chua TP, Anker SD, Francis DP, Doehner W, Banasiak W, et al. Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity: an ominous sign in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:544–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jennett S, McKay FC, Moss VA. The human ventilatory response to stimulation by transient hypoxia. J Physiol. 1981;315:339–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haldane J, Smith JL. The physiological effects of air vitiated by respiration. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1892;1:168–86. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Read DJ. A clinical method for assessing the ventilatory response to carbon dioxide. Australas Ann Med. 1967;16:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duffin J Measuring the ventilatory response to hypoxia. J Physiol. 2007;584:285–93.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giannoni A, Emdin M, Poletti R, Bramanti F, Prontera C, Piepoli M, Passino C. Clinical significance of chemosensitivity in chronic heart failure: influence on neurohormonal derangement, Cheyne–Stokes respiration and arrhythmias. Clin Sci. 2008;114:489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nielsen M, Smith H. Studies on the regulation of respiration in acute hypoxia; with a appendix on respiratory control during prolonged hypoxia. Acta Physiol Scand 1952;24:293–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paton JFR, Ratcliffe L, Hering D, Wolf J, Sobotka PA, Narkiewicz K. Revelations about carotid body function through its pathological role in resistant hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15:273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Niewinski P, Tubek S, Banasiak W, Paton JFR, Ponikowski P. Consequences of peripheral chemoreflex inhibition with low-dose dopamine in humans. J Physiol. 2014;592:1295–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mozer MT, Holbein WW, Joyner MJ, Curry TB, Limberg JK. Reductions in carotid chemoreceptor activity with low-dose dopamine improves baroreflex control of heart rate during hypoxia in humans. Physiol Rep Physiol Rep; 2016;4:e12859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Somers VK, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Potentiation of sympathetic nerve responses to hypoxia in borderline hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1988;11:608–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paton JFR, Sobotka PA, Fudim M, Engelman ZJ, Engleman ZJ, Hart ECJ, et al. The carotid body as a therapeutic target for the treatment of sympathetically mediated diseases. Hypertension. 2013;61:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Younes M, Ostrowski M, Thompson W, Leslie C, Shewchuk W. Chemical control stability in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.White DP. Pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1363–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leung RST. Sleep-Disordered Breathing: Autonomic Mechanisms and Arrhythmias. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:324–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mansukhani MP, Wang S, Somers VK. Chemoreflex physiology and implications for sleep apnoea: insights from studies in humans. Exp Physiol. 2015;100:130–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Francis DP, Willson K, Davies LC, Coats AJ, Piepoli M. Quantitative general theory for periodic breathing in chronic heart failure and its clinical implications. Circulation. 2000;102:2214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giannoni A, Gentile F, Navari A, Borrelli C, Mirizzi G, Catapano G, et al. Contribution of the Lung to the Genesis of Cheyne-Stokes Respiration in Heart Failure: Plant Gain Beyond Chemoreflex Gain and Circulation Time. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giannoni A, Gentile F, Sciarrone P, Borrelli C, Pasero G, Mirizzi G, et al. Upright Cheyne-Stokes Respiration in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2934–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central Sleep Apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:141–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hall MJ, Xie A, Rutherford R, Ando S, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Cycle length of periodic breathing in patients with and without heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:376–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oldenburg O, Wellmann B, Buchholz A, Bitter T, Fox H, Thiem U, et al. Nocturnal hypoxaemia is associated with increased mortality in stable heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Emdin M, Mirizzi G, Giannoni A, Poletti R, Iudice G, Bramanti F, et al. Prognostic Significance of Central Apneas Throughout a 24-Hour Period in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1351–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borrelli C, Gentile F, Sciarrone P, Mirizzi G, Vergaro G, Ghionzoli N, et al. Central and Obstructive Apneas in Heart Failure With Reduced, Mid-Range and Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buchanan GF, Richerson GB. Role of chemoreceptors in mediating dyspnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chua TP, Clark AL, Amadi AA, Coats AJ. Relation between chemosensitivity and the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Arzt M, Harth M, Luchner A, Muders F, Holmer SR, Blumberg FC, et al. Enhanced ventilatory response to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure and central sleep apnea. Circulation. 2003;107:1998–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chua TP, Ponikowski PP, Harrington D, Chambers J, Coats AJ. Contribution of peripheral chemoreceptors to ventilation and the effects of their suppression on exercise tolerance in chronic heart failure. Heart. 1996;76:483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chua TP, Harrington D, Ponikowski P, Webb-Peploe K, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ. Effects of dihydrocodeine on chemosensitivity and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Murphy RM, Shah RV, Malhotra R, Pappagianopoulos PP, Hough SS, Systrom DM, et al. Exercise oscillatory ventilation in systolic heart failure: an indicator of impaired hemodynamic response to exercise. Circulation. 2011;124:1442–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ponikowski P, Chua TP, Piepoli M, Ondusova D, Webb-Peploe K, Harrington D, et al. Augmented peripheral chemosensitivity as a potential input to baroreflex impairment and autonomic imbalance in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1997;96:2586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Francis DP, Davies LC, Willson K, Ponikowski P, Coats AJ, Piepoli M. Very-low-frequency oscillations in heart rate and blood pressure in periodic breathing: role of the cardiovascular limb of the hypoxic chemoreflex. Clin Sci (Lond). 2000;99:125–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Joyner MJ. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of autonomic function in humans. J Physiol. 2016;594:4009–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xing DT, May CN, Booth LC, Ramchandra R. Tonic arterial chemoreceptor activity contributes to cardiac sympathetic activation in mild ovine heart failure. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:1031–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun SY, Wang W, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Enhanced peripheral chemoreflex function in conscious rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Giannoni A, Raglianti V, Mirizzi G, Taddei C, Del Franco A, Iudice G, et al. Influence of central apneas and chemoreflex activation on pulmonary artery pressure in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Giannoni A, Raglianti V, Taddei C, Borrelli C, Chubuchny V, Vergaro G, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration related oscillations in cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2019;289:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ottaviani MM, Wright L, Dawood T, Macefield VG. In vivo recordings from the human vagus nerve using ultrasound-guided microneurography. J Physiol. 2020;598:3569–3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ponikowski P, Chua TP, Anker SD, Francis DP, Doehner W, Banasiak W, et al. Peripheral chemoreceptor hypersensitivity: an ominous sign in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:544–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Giannoni A, Gentile F, Buoncristiani F, Borrelli C, Sciarrone P, Spiesshoefer J, et al. Chemoreflex and Baroreflex Sensitivity Hold a Strong Prognostic Value in Chronic Heart Failure. JACC Hear Fail. 2022;10:662–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McBryde FD, Abdala AP, Hendy EB, Pijacka W, Marvar P, Moraes DJA, et al. The carotid body as a putative therapeutic target for the treatment of neurogenic hypertension. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Narkiewicz K, Ratcliffe LEK, Hart EC, Briant LJB, Chrostowska M, Wolf J, et al. Unilateral Carotid Body Resection in Resistant Hypertension: A Safety and Feasibility Trial. JACC Basic to Transl Sci. 2016;1:313–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pijacka W, Moraes DJA, Ratcliffe LEK, Nightingale AK, Hart EC, Silva MP Da, et al. Purinergic receptors in the carotid body as a new drug target for controlling hypertension. Nat Med. 2016;22:1151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jackson KL, Dampney BW, Moretti J-L, Stevenson ER, Davern PJ, Carrive P, Head GA. Contribution of Orexin to the Neurogenic Hypertension in BPH/2J Mice. Hypertension 2016;67:959–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sun H, Palcza J, Card D, Gipson A, Rosenberg R, Kryger M, et al. Effects of Suvorexant, an Orexin Receptor Antagonist, on Respiration during Sleep In Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.White DP. Pharmacologic Approaches to the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sleep Med Clin 2016;11:203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sutton FD, Zwillich CW, Creagh CE, Pierson DJ, Weil JV. Progesterone for outpatient treatment of Pickwickian syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1975;83:476–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Javaheri S, Guerra L. Effects of domperidone and medroxyprogesterone acetate on ventilation in man. Respir Physiol. 1990;81:359–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Javaheri S, Brown LK, Khayat RN. Update on Apneas of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: Emphasis on the Physiology of Treatment: Part 2: Central Sleep Apnea. Chest. 2020;157:1637–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Contini M, Apostolo A, Cattadori G, Paolillo S, Iorio A, Bertella E, et al. Multiparametric comparison of CARvedilol, vs. NEbivolol, vs. BIsoprolol in moderate heart failure: the CARNEBI trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2314–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Agostoni P, Contini M, Magini A, Apostolo A, Cattadori G, Bussotti M, et al. Carvedilol reduces exercise-induced hyperventilation: A benefit in normoxia and a problem with hypoxia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li Y-L, Xia X-H, Zheng H, Gao L, Li Y-F, Liu D, et al. Angiotensin II enhances carotid body chemoreflex control of sympathetic outflow in chronic heart failure rabbits. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cundrle I Jr, Johnson BD, Rea RF, Scott CG, Somers VK, Olson LJ. Modulation of ventilatory reflex control by cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Card Fail. 2015;21:367–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mezzani A, Pistono M, Agostoni P, Giordano A, Gnemmi M, Imparato A, et al. Exercise gas exchange in continuous-flow left ventricular assist device recipients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0187112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Apostolo A, Paolillo S, Contini M, Vignati C, Tarzia V, Campodonico J, et al. Comprehensive effects of left ventricular assist device speed changes on alveolar gas exchange, sleep ventilatory pattern, and exercise performance. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ciarka A, Cuylits N, Vachiery J-L, Lamotte M, Degaute J-P, Naeije R, et al. Increased peripheral chemoreceptors sensitivity and exercise ventilation in heart transplant recipients. Circulation. 2006;113:252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bitter T, Westerheide N, Hossain MS, Lehmann R, Prinz C, Kleemeyer A, et al. Complex sleep apnoea in congestive heart failure. Thorax. 2011;66:402–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Costanzo MR, Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, Augostini R, Goldberg L, Holcomb R, et al. Transvenous neurostimulation for central sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:974–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Imadojemu VA, Mawji Z, Kunselman A, Gray KS, Hogeman CS, Leuenberger UA. Sympathetic chemoreflex responses in obstructive sleep apnea and effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2007;131:1406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Spicuzza L, Bernardi L, Balsamo R, Ciancio N, Polosa R, Di Maria G. Effect of treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure on ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 2006;130:774–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fontana M, Emdin M, Giannoni A, Iudice G, Baruah R, Passino C. Effect of acetazolamide on chemosensitivity, Cheyne-Stokes respiration, and response to effort in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lorenzi-Filho G, Rankin F, Bies I, Douglas Bradley T. Effects of inhaled carbon dioxide and oxygen on cheyne-stokes respiration in patients with heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Borrelli C, Aimo A, Mirizzi G, Passino C, Vergaro G, Emdin M, et al. How to take arms against central apneas in heart failure. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;15:743–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Giannoni A, Baruah R, Willson K, Mebrate Y, Mayet J, Emdin M, et al. Real-time dynamic carbon dioxide administration: a novel treatment strategy for stabilization of periodic breathing with potential application to central sleep apnea. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1832–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marcus NJ, Rio R Del, Schultz EP, Xia X-H, Schultz HD. Carotid body denervation improves autonomic and cardiac function and attenuates disordered breathing in congestive heart failure. J Physiol. 2014;592:391–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Del Rio R, Marcus NJ, Schultz HD. Carotid chemoreceptor ablation improves survival in heart failure: rescuing autonomic control of cardiorespiratory function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Niewinski P, Janczak D, Rucinski A, Tubek S, Engelman ZJ, Piesiak P, et al. Carotid body resection for sympathetic modulation in systolic heart failure: results from first-in-man study. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Giannoni A, Passino C, Mirizzi G, Franco A Del, Aimo A, Emdin M. Treating chemoreflex in heart failure: modulation or demolition? J Physiol 2014;592:1903–4.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tubek S, Niewinski P, Reczuch K, Janczak D, Rucinski A, Paleczny B, et al. Effects of selective carotid body stimulation with adenosine in conscious humans. J Physiol. 2016;594:6225–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Niewinski P, Janczak D, Rucinski A, Tubek S, Engelman ZJ, Jazwiec P, et al. Dissociation between blood pressure and heart rate response to hypoxia after bilateral carotid body removal in men with systolic heart failure. Exp Physiol. 2014;99:552–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Notarius CF, Atchison DJ, Rongen GA, Floras JS. Effect of adenosine receptor blockade with caffeine on sympathetic response to handgrip exercise in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;281:H1312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sacramento JF, Gonzalez C, Gonzalez-Martin MC, Conde SV. Adenosine Receptor Blockade by Caffeine Inhibits Carotid Sinus Nerve Chemosensory Activity in Chronic Intermittent Hypoxic Animals. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015;860:133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, Liming JD, Lindower P, Roselle GA. Effect of Theophylline on Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1996;335:562–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Javaheri S, Guerra L. Lung function, hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory responses, and respiratory muscle strength in normal subjects taking oral theophylline. Thorax. 1990;45:743–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Del Rio R, Marcus NJ, Schultz HD. Inhibition of hydrogen sulfide restores normal breathing stability and improves autonomic control during experimental heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:1141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Haack KK V, Marcus NJ, Rio R Del, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Simvastatin Treatment Attenuates Increased Respiratory Variability and Apnea/Hypopnea Index in Rats With Chronic Heart Failure. Hypertension. 2014;63:1041–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Javaheri A, Rader DJ, Javaheri S. Statin therapy in heart failure: is it time for a second look? Hypertension. 2014;63;909–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yamauchi M, Dostal J, Kimura H, Strohl KP. Effects of buspirone on posthypoxic ventilatory behavior in the C57BL/6J and A/J mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Taylor NC, Li A, Nattie EE. Medullary serotonergic neurones modulate the ventilatory response to hypercapnia, but not hypoxia in conscious rats. J Physiol. 2005;566:543–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Messier ML, Li A, Nattie EE. Inhibition of medullary raphé serotonergic neurons has age-dependent effects on the CO2 response in newborn piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1909–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Giannoni A, Borrelli C, Mirizzi G, Richerson GB, Emdin M, Passino C. Benefit of buspirone on chemoreflex and central apnoeas in heart failure: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23;312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Spicuzza L, Gabutti A, Porta C, Montano N, Bernardi L. Yoga and chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Lancet. 2000;356:1495–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zurek M, Corrà U, Piepoli MF, Binder RK, Saner H, Schmid JP. Exercise training reverses exertional oscillatory ventilation in heart failure patients. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zeitler EP, Abraham WT. Novel Devices in Heart Failure: BAT, Atrial Shunts, and Phrenic Nerve Stimulation. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8:251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Heusser K, Thöne A, Lipp A, Menne J, Beige J, Reuter H, et al. Efficacy of Electrical Baroreflex Activation Is Independent of Peripheral Chemoreceptor Modulation. Hypertension 2020;75;257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]