Abstract

Although four varicella-zoster virus (VZV) genes have been shown to be transcribed in latently infected human ganglia, their role in the development and maintenance of latency is unknown. To study these VZV transcripts, we decided first to localize their expression products in productively infected cells. We began with VZV gene 21, whose open reading frame (ORF) is 3,113 bp. We cloned the 5′ and 3′ ends and the predicted antigenic segments of the ORF as 1292-, 1280-, and 880-bp DNA fragments, respectively, into the prokaryotic expression vector pGEX-2T. The three VZV 21 ORFs were expressed as approximately 75-, 73-, and 59-kDa glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. To prepare polyclonal antibodies that would recognize all potential epitopes on the VZV gene 21 protein, rabbits were inoculated with a mixture of the three fusion proteins, and antisera were obtained and affinity purified. Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic analyses using these antibodies revealed VZV ORF 21 protein in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of VZV-infected cells. When these antibodies were applied to purified VZV nucleocapsids, intense staining was seen in their central cores.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes varicella (chickenpox), becomes latent in ganglia, and reactivates to produce zoster (shingles). A knowledge of the physical state and expression of VZV genes during latency is central to predictions regarding the prevention of reactivation. The 124-kbp double-stranded VZV DNA contains 71 open reading frames (ORFs) that encode 68 proteins. Analysis of a cDNA library prepared from RNA extracted from latently infected human ganglia revealed the transcription of VZV genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 (2, 3). VZV gene 29 encodes a major DNA-binding protein (11), and genes 62 and 63 encode immediate-early genes (5, 7). Although the function of VZV gene 21 is unknown, its herpes simplex virus (HSV) homolog (the UL37 protein) exists in the nucleus and cytoplasm of infected cells (14, 17). HSV UL37 complexes with the DNA-binding protein HSV ICP8 (18). To study VZV ORF 21 further, we produced fusion proteins and monospecific polyclonal antibodies against VZV ORF 21 and used them to localize VZV gene 21 protein in VZV-infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

We propagated VZV in BSC-1 cells by cocultivating semiconfluent cultures with trypsinized infected cells as described previously (10).

Vectors, enzymes, and chemicals.

We obtained the glutathione S-transferase fusion vector (pGEX-2T), the GST gene fusion system, and thrombin protease from Pharmacia Biotech, Inc. (Piscataway, N.J.), restriction enzymes and DNA-modifying enzymes from Bethesda Research Laboratories (Gaithersburg, Md.), calf alkaline phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail (complete) from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals (Indianapolis, Ind.), iodoacetamide, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and DNase I from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.), radiochemicals from ICN Pharmaceuticals (Costa Mesa, Calif.), and the Vectastain Elite kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.).

Primers.

We chose VZV-specific oligonucleotide primers from published sequences (4). VZV ORF 21 is located between nucleotides 30759 and 33872 on the virus genome. In primer P1 (5′-CTCAGCGTAGAATATACCATGGAA-3′), located between nucleotides 30741 and 30764 on the VZV genome, the first nucleotide (at position 30741 on the VZV genome) was changed from G to C. Primer P2 (5′-ACCCACTAAAGCGAGACATCC-3′) is located between nucleotides 32013 and 32033, and primer P3 (5′-ATACAAACGAAACGCCCAGTCAATA-3′) is located between nucleotides 33920 and 33945 on the VZV genome.

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

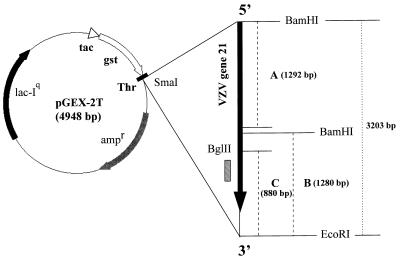

Plasmid pGEX-2T was digested with SmaI and dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. We used primers P1 and P2 to amplify a 1,292-bp segment of VZV DNA (Fig. 1, segment A) by PCR; the fragment was then blunt ended and ligated to SmaI-treated, dephosphorylated pGEX-2T. We used the ligation mixture to transform Escherichia coli BL21 and selected ampicillin-resistant colonies for propagation. We used primers P1 and P3 to amplify a 3,203-bp DNA fragment containing the complete VZV gene 21 ORF by PCR; the fragment was then blunt ended and ligated to SmaI-digested, dephosphorylated pGEX-2T. The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli BL21, and ampicillin-resistant colonies were selected for propagation. The recombinant clone was digested with BamHI, and the large 6,228-bp fragment (containing fragment B) was purified from a 1% agarose gel by using Geneclean kit (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.). We religated the 6,228-bp BamHI fragment and used it to transform E. coli BL21; ampicillin-resistant colonies were selected for propagation.

FIG. 1.

Cloning of fragments containing VZV ORF 21 into the pGEX-2T expression vector. We cloned three different portions of VZV ORF 21 DNA into pGEX-2T as follows. For clone A, a 1,292-bp fragment containing the 5′ end of VZV ORF 21 was PCR amplified, blunt ended, and cloned at the unique SmaI site of pGEX-2T, and a 3,203-bp DNA fragment containing the complete VZV gene 21 ORF was PCR amplified, blunt ended, and cloned at the SmaI site of pGEX-2T. For clone B, we digested the recombinant clone containing the 3,203-bp insert with BamHI, and the large fragment containing the 4,948-bp vector and 1,280-bp portion of the insert containing the 3′ end of VZV ORF 21 was religated. For clone C, we cut the recombinant clone containing the complete 3,203-bp VZV ORF 21 insert with BamHI and BglII and religated the large fragment containing the 4,948-bp vector and 880-bp portion of the insert containing a predicted antigenic site (hatched rectangle). The locations of the ampicillin resistance gene (ampr), lacIq gene (lacIq), tac promoter (tac), gst promoter (gst), thrombin cleavage site (Thr), and the multiple restriction sites are indicated.

Using the PC/GENE program (Intelligenetics Inc., Mountain View, Calif.), we identified the region between nucleotides 33087 and 33107 on the VZV genome (4) as encoding one of the most hydrophilic regions within VZV ORF 21. Regions with high hydrophilicity are likely to be highly antigenic. Therefore, in addition to the 5′ and 3′ ends of VZV ORF 21, we cloned a segment containing the region of high hydrophilicity as a separate GST fusion protein. The recombinant clone containing the complete 3,203-bp VZV 21 ORF insert described above was cut with BamHI and BglII, and the large (5,828-bp) fragment (containing fragment C) was purified from a 1% agarose gel. The 5,828-bp BglII-BamHI fragment was religated and used to transform E. coli BL21, and ampicillin-resistant colonies were selected for propagation.

Expression and purification of GST fusion proteins.

We prepared fusion proteins from E. coli BL21 containing the recombinant clones (Fig. 1, segments A, B, and C) as described previously (8), with minor modifications. Briefly, we induced expression with 100 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) in 100-ml cultures containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). The bacterial cell pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in the presence of protease inhibitors (1 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and one tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals), treated with 10 μg of DNase I per ml in 1 mM MnCl2–10 mM MgCl2 on ice for 1 h, and solubilized with 1.5% Sarkosyl–2% Triton X-100. We mixed a small portion (20 μl) of each lysate with an equal volume of 2× sample buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.2% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.03% bromophenol blue) and analyzed it by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel.

We processed the GST fusion proteins in the lysates by using a Bulk GST purification module (Pharmacia Biotech). Proteins were bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads and washed extensively as instructed by the manufacturer. Because the fusion proteins were highly insoluble under these conditions and could not be eluted from beads with buffers recommended by the manufacturer, we analyzed a small portion (20 μl) of the washed beads on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel as described above.

Preparation of rabbit antiserum against the VZV ORF 21 fusion proteins.

The glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads carrying the fusion proteins were loaded on preparative SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels, and the protein bands were visualized by staining with 4 M sodium acetate. Gel slices containing the fusion proteins were dialyzed extensively in water, lyophilized for 16 h, powdered, resuspended in PBS, and mixed with Freund’s complete adjuvant for subcutaneous inoculation into rabbits as described previously (11). Rabbits were boosted once a month for 5 months with a mixture of the gel containing the fusion proteins and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. A 1:10 dilution of the rabbit antiserum was adsorbed with uninfected BSC-1 cells at 37°C for 1 h and at 4°C for 16 h. The adsorbed antiserum was immunoprecipitated with 35S-labeled extracts of uninfected and VZV-infected BSC-1 cells as described previously (24). We exposed the fluorograph to Amersham Hyperfilm-MP for 16 h at room temperature.

Western blot analysis of GST fusion proteins with rabbit antiserum.

Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (15 μl) containing 1 to 2 μg of each of the three fusion proteins were digested with 0.3 U of thrombin and loaded onto an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel. A Western blot was prepared as described previously (23) and incubated with VZV ORF 21 antiserum (ANTI-21) followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), nitroblue tetrazolium, and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate for detection as described previously (16).

Affinity purification of ANTI-21.

Two hundred microliters of glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads containing the fusion proteins was incubated with 10 U of thrombin protease at room temperature for 16 h, loaded onto an SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel, and electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose as described previously (11). The antisera were affinity purified by using the VZV ORF 21 portion of the thrombin-cleaved fusion proteins on the nitrocellulose membranes as described previously (15), with minor modifications. Briefly, the proteins on the nitrocellulose membranes were visualized with Ponceau S stain (Sigma) dialyzed in water to remove the stain, and air dried. We pooled the membrane strips containing the free VZV ORF 21 proteins and placed them in 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min, followed by ANTI-21 diluted 1:100 in 4% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The strips were washed three times with PBS and soaked briefly in 0.01 M sodium phosphate (pH 6.8). We eluted the VZV-specific antibodies by soaking the strips at room temperature twice for 4 min each time in 500 μl of 100 mM glycine–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.5). The eluate was immediately neutralized with 0.1 volume of 1 M sodium phosphate (pH 8.6) and used for histochemical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry.

We applied affinity-purified ANTI-21 to acetone-fixed uninfected and VZV-infected BSC-1 cells as described previously (13).

Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of VZV-infected BSC-1 cells.

Cells grown in 35-mm-diameter Permanox dishes were rinsed with 0.08 M sucrose in PBS (SS buffer) and fixed in a mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde, 15% saturated picric acid, and 0.05% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (21) on ice for 1 h, rinsed with SS buffer, incubated in 1% sodium borohydride for 30 min at room temperature, and rinsed again in SS buffer. The cells were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with affinity-purified rabbit ANTI-21, rinsed with SS buffer, incubated with a 1:300 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed with SS buffer, incubated with avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC reagent; Vectastain Elite kit) for 1 h at room temperature, and rinsed with SS buffer. We obtained the reaction product by incubating the cells with a buffer containing diaminobenzidine, hydrogen peroxide, and nickel (Vector kit) for 2 min. After being rinsed again with SS buffer, the cells were postfixed with 1% OsO4–0.08 M sucrose in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer for 30 min, rinsed with SS buffer, and dehydrated in 50, 70, 95, and 100% ethanol followed by propylene oxide. We embedded the cells with Spurr’s resin and, after polymerization, cut thin sections with a Reichert Ultracut E microtome. We analyzed and photographed the cells with a Philips CM 10 electron microscope at 80 kV without additional counterstaining. The negatives were scanned with a UMAX UC840 at 1,200 dots/in. or digitized in Kodak Photo CD pro format. Digitized images were processed with Adobe Photoshop on a Power Macintosh 7100.

Preparation of VZV nucleocapsids.

We prepared VZV nucleocapsids as described previously (22) and fixed the pellets of nucleocapsids on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde–15% saturated picric acid–0.05% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorenson’s phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.08 M sucrose for 3.5 h. We then washed the pellets and stored them in PBS containing 0.05% NaN3 at 4°C.

Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of VZV nucleocapsids.

The pellets containing fixed nucleocapsids were resuspended, transferred to an Eppendorf tube, and centrifuged (12,000 × g) for 5 min. All but approximately 200 μl of supernatant was aspirated mixed rapidly with 200 μl of 2% SeaKem agarose (FMC, Rockland, Maine) at 60°C, and dispersed between two prewarmed glass slides separated by no. 2 glass coverslips. We placed the glass slides at 4°C to gel the agarose. We then cut the agarose gel pieces into 1- to 2-mm squares and placed them into the wells of a 24-well plastic dish containing PBS (6). The agarose pieces were then treated with 1% sodium borohydride in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed three times with PBS, blocked with 4% BSA in PBS containing 0.05% NaN3 and 1.5% normal goat serum (blocking solution) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with a 1:10 dilution of either rabbit ANTI-21 or 1:10 normal rabbit serum (NRS), both of which had been affinity purified and adsorbed against both uninfected BSC-1 cells and a 10% homogenate of human liver at room temperature for 15.5 h. We rinsed the agarose pieces four times with PBS and once with the blocking solution. After 5 min, we added a 1:200 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vectastain Elite kit) and incubated the mixture for 2.25 h at room temperature. The pieces were then rinsed three times with PBS, incubated with 2% BSA in PBS containing ABC reagent (Vectastain Elite kit) for 2 h at room temperature, rinsed four times with PBS, incubated for 2 min in diamino-benzidine-H2O2-nickel solution (Vector kit) at room temperature, and rinsed again four times with PBS. Samples were then processed and examined as described for the cultured cells.

RESULTS

Expression of portions of VZV ORF 21 in E. coli and preparation of rabbit antiserum.

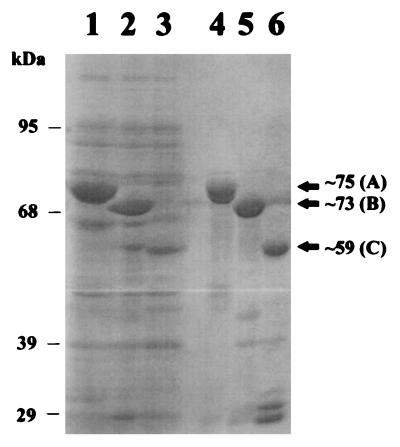

We cloned three portions (the 5′ end, the 3′ end, and the predicted antigenic segment) of the ORF into a GST fusion vector (pGEX-2T) as described in Fig. 1. We used the three recombinant clones A, B, and C (Fig. 1) to express the respective portions of the VZV ORF 21 as GST fusion proteins in E. coli. PAGE analysis of the lysates from E. coli containing the recombinant clones A, B, and C displayed prominent bands at ∼75, ∼73, and ∼59 kDa (Fig. 2, lanes 1, 2, and 3, respectively); Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 6, also shows purified forms of the fusion proteins bound to the Sepharose beads. Rabbit polyclonal antisera were raised against a mixture of all three of the 75-, 73-, and 59-kDa fusion protein bands excised from an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The antiserum was then affinity purified as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 2.

Expression in E. coli of portions of VZV ORF 21 as GST fusion proteins. We used the recombinant clones (Fig. 1, A, B, and C) containing portions of VZV ORF 21 to transform E. coli BL21. We induced expression of fusion proteins in 100-ml cultures with 100 mM IPTG. The fusion proteins were prepared in the presence of protease inhibitors and solubilized with 1.5% Sarkosyl–2% Triton X-100. The GST fusion proteins in the lysates were bound to GST-agarose beads and washed as described in Materials and Methods. Twenty microliters of the lysate prepared from recombinant clones A, B, and C (lanes 1, 2, and 3, respectively) and 20 μl of the washed beads (lanes 4 to 6) were loaded onto an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel.

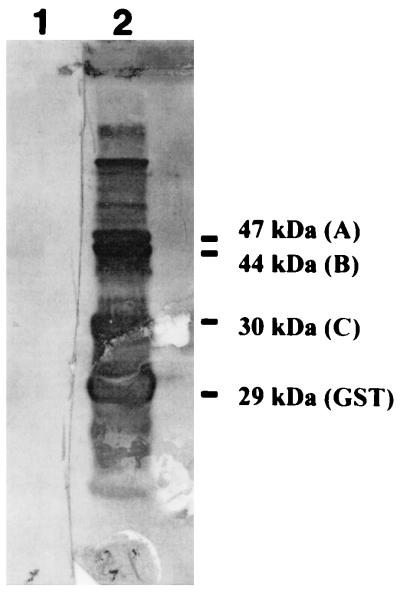

Western blot analysis of GST fusion proteins with ANTI-21.

The glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads carrying the fusion proteins were digested with thrombin and analyzed by Western blotting using the rabbit antiserum raised against the fusion proteins. Our results showed that the rabbit antiserum reacted with the three VZV ORF 21 polypeptides (47, 44, and 30 kDa) and the 29-kDa GST protein, indicating that the rabbit antiserum contained antibodies specific for the VZV ORF 21 polypeptides (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of GST fusion proteins of VZV gene 21 peptides, using rabbit antiserum raised against VZV gene 21 peptides. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads containing 1 to 2 μg of each of the three fusion proteins were digested with thrombin and loaded onto an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, reacted with either NRS (lane 1) or ANTI-21 (lane 2), and visualized as described in Materials and Methods. The locations and the sizes of the three VZV ORF 21 polypeptides (A, B, and C) and GST are shown.

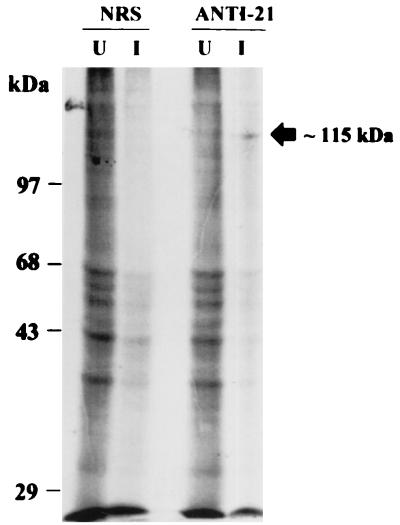

Identification of VZV gene 21 protein in virus-infected cells.

Immunoprecipitation of 35S-labeled uninfected and VZV-infected BSC-1 cell lysates with NRS and rabbit ANTI-21 showed detection of the 115-kDa VZV gene 21 protein with ANTI-21 but not with NRS (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Immunoprecipitation of VZV gene 21 protein with ANTI-21. Uninfected (U) and VZV-infected (I) BSC-1 cells were labeled with 50 μCi of [35S]methionine per ml, immunoprecipitated with NRS or ANTI-21, and analyzed (50,000 to 100,000 cpm) by SDS-PAGE (8% gel). The location of the ∼115-kDa VZV gene 21 protein detected with ANTI-21 and the locations of molecular weight standards (Bethesda Research Laboratories) are indicated.

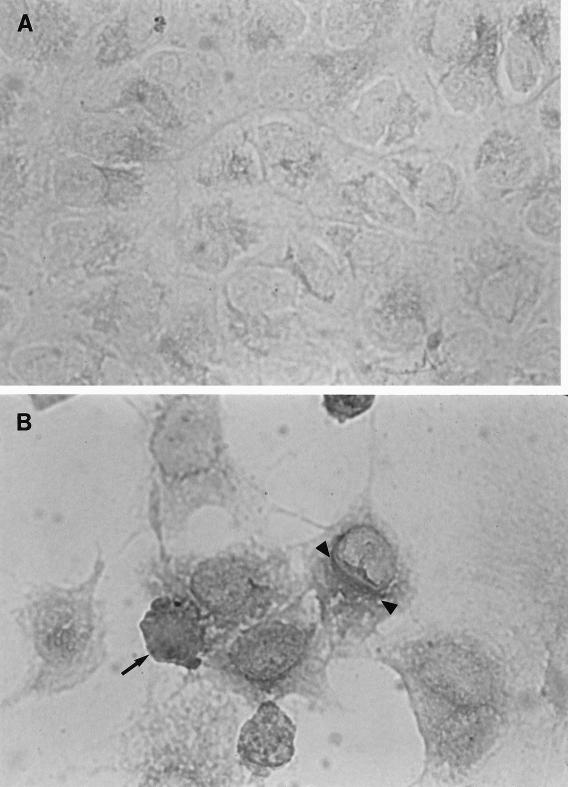

Immunohistochemical analysis of entire coverslips containing >106 acetone-fixed uninfected and VZV-infected BSC-1 cells with ANTI-21 showed VZV gene 21 protein in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of virus-infected cells. Positive dark red staining, indicating the presence of VZV gene 21 protein, was associated with the characteristic focal cytopathic effect produced by VZV (Fig. 5B). We did not see staining in uninfected cells (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Immunohistochemical staining patterns of uninfected (A) and VZV-infected (B) BSC-1 cells after incubation with rabbit ANTI-21. Cells on coverslips were infected with VZV. Two days later, we fixed the cells in acetone and detected VZV gene 21 protein with rabbit ANTI-21 followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG and streptavidin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, as described in Materials and Methods. We used new fuchsin substrate as a chromogen for detection. Positive staining is seen in both the nucleus (arrow) and the cytoplasm (arrowheads) of VZV-infected cells. Magnification, ×216.

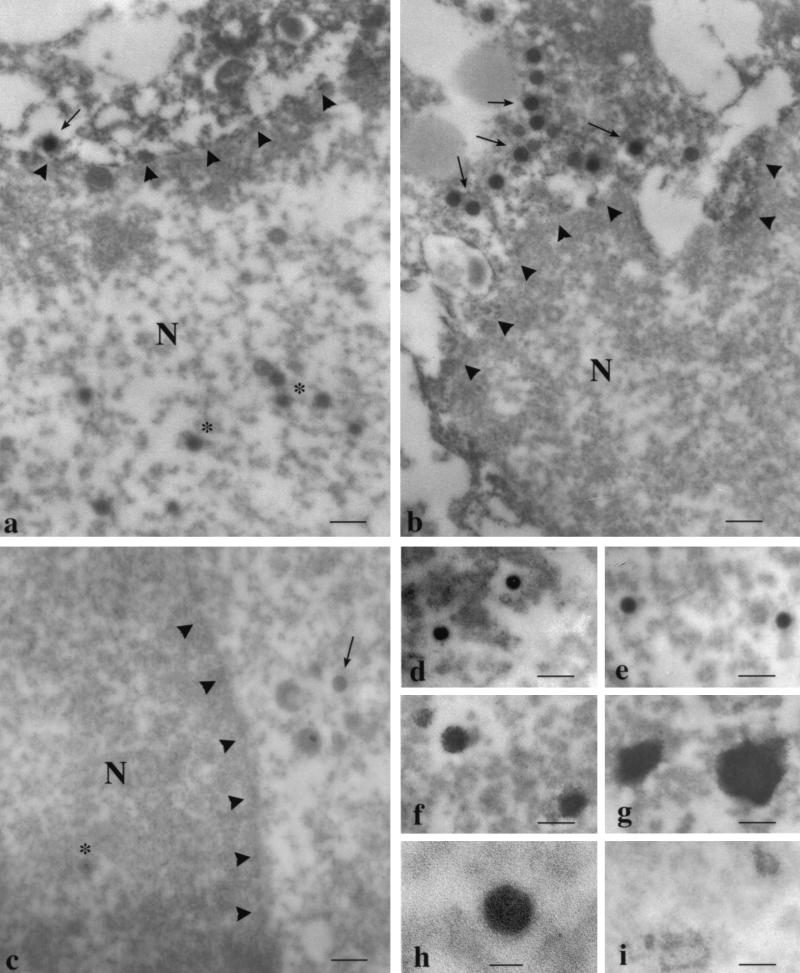

We further localized the positive staining in VZV-infected cells by immunoelectron microscopy (Fig. 6). We examined approximately a dozen cells. An intense VZV gene 21 signal was associated with developing virus particles both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. We did not quantitate virus particles. Positive staining of purified virus nucleocapsids with the same antibody confirmed its specificity. Controls using specific antibody with uninfected cells or NRS either with uninfected or VZV-infected cells or nucleocapsids showed no reaction product over the virus particles or nucleocapsids. The size of the icosahedral virus nucleocapsid was approximately 80 to 100 nm (Fig. 6h). The intact VZV particle has been shown to be 180 to 200 nm in size (8). Therefore, absence of positive staining in the 100-nm area immediately adjacent to the nucleocapsid suggests that VZV ORF 21 is not associated with the tegument. The positive stain on a few virus particles was fainter (Fig. 6b) but still darker than the stain on particles reacted with NRS (Fig. 6c). One possible reason for the reduced intensity is the tangential nature of the section of the particles in Fig. 6b.

FIG. 6.

Immunoelectron microscopic localization of VZV gene 21 protein in VZV-infected BSC-1 cells and in purified nucleocapsids. We incubated the fixed VZV-infected BSC-1 cells (a to c) or purified VZV nucleocapsids (d to i) with rabbit ANTI-21 followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, ABC reagent, and chromogen and prepared them for electron microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoreactive virus particles are seen both in the cytoplasm (arrows in panels a and b) and in the nucleus (asterisk in panel a). The location of the nuclear membrane is indicated by arrowheads in panels a to c. NRS did not react with the virus particles (arrow and asterisk in panel c). Immunoreactive cores of nucleocapsids (d and e) and aggregates of nucleocapsids (f and g) are shown. A higher magnification of an immunoreactive nucleocapsid core reveals their characteristic hexagonal shape (h). NRS did not show positive staining with the purified nucleocapsids (i). Bars = 200 nm (a to g and i) and 50 nm (h).

DISCUSSION

We expressed three different portions of VZV ORF 21 (the 5′ end, the 3′ end, and the predicted antigenic segment) as GST fusion proteins. The observed sizes of the three fusion proteins (∼75, ∼73, and ∼59 kDa) agreed with their predicted sizes based on VZV sequence data (4) and the known size of the native GST protein (20). Antibodies were raised in rabbits and then affinity purified. The antiserum directed against the three fusion proteins detected a faint band of approximately 115 kDa in virus-infected cell lysates (Fig. 4), corresponding to the value predicted from the amino acid sequence (4). The low intensity of the VZV ORF 21 band seen by immunoprecipitation suggests that the virus-encoded protein is labile or is expressed at a low level or arises from low affinity of the antisera. The weak gene 21 signal is not likely to be due to a low-level production of VZV proteins since routine immunoprecipitations in our laboratory using antibodies against other structural proteins have always yielded brighter bands (24). Furthermore, Western blot analysis of VZV-infected BSC-1-cell lysates also showed a weak band at 115 kDa (data not shown). Since immunohistochemical analysis of virus-infected cells with our affinity-purified antiserum produced a dark purple signal, it is unlikely that this antiserum is low affinity.

Like its HSV UL37 homolog (47% similarity at the amino acid level), we saw VZV gene 21 protein in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of virus-infected cells (14, 17, 19). HSV UL37 has been shown by detergent solubilization and protease treatment to be associated with the tegument of the HSV virion (17). However, our results indicate that VZV ORF 21 protein is not associated with the tegument (Fig. 5h). HSV UL37 has also been shown to be a phosphoprotein that forms a complex with the DNA-bound HSV ICP8 (1, 18). Further analysis of VZV gene 21 protein is needed to determine its kinetic class, whether it is phosphorylated, and if it is associated with VZV ORF 29, a major DNA-binding protein homologous to HSV ICP8.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mark Burgoon for useful suggestions, Lisa Schneck and Mary Devlin for editorial review, and Cathy Allen for preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AG 06127 and NS32623 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albright A G, Jenkins F J. The herpes simplex virus UL37 protein is phosphorylated in infected cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4842–4847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4842-4847.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohrs R, Barbour M, Gilden D H. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: detection of transcripts mapping to genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 in a cDNA library enriched for VZV RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2789–2796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2789-2796.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohrs R, Schrock K, Barbour M, Owens G, Mahalingam R, Devlin M E, Wellish M, Gilden D H. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: construction of a cDNA library from latently infected human trigeminal ganglia and detection of a VZV transcript. J Virol. 1994;68:7900–7908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7900-7908.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison A J, Scott J E. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:1759–1816. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-9-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Nikkels A F, Piette J, Rentier B. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63 encodes an immediate-early protein that is abundantly expressed during latency. J Virol. 1995;69:3240–3245. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3240-3245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Camilli P, Harris S M, Huttner W B, Greengard P. Synapsin I (protein I), a nerve terminal-specific phosphoprotein. II. Its specific association with synaptic vesicles demonstrated by immunocytochemistry and in agarose-embedded synaptosomes. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1355–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forghani B, Mahalingam R, Vafai A, Hurst J W, Dupuis K W. Monoclonal antibody to immediate early protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus gene 62. Virus Res. 1990;16:195–210. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(90)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frangioni J V, Neel B G. Solubilization and purification of enzymatically active glutathione S-transferase (pGEX) fusion proteins. Anal Biochem. 1993;210:179–187. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelb L D. Varicella-zoster virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. Virology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Raven Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 2011–2054. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilden D H, Shtram Y, Friedmann A, Wellish M, Devlin M, Cohen A, Fraser N, Becker Y. Extraction of cell-associated varicella-zoster virus DNA with triton X-100-NaCl. J Virol Methods. 1982;4:263–275. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(82)90073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. pp. 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinchington P R, Inchauspe G, Subak-Sharpe J H, Robey F, Hay J, Ruyechan W T. Identification and characterization of a varicella-zoster virus DNA-binding protein by using antisera directed against a predicted synthetic oligopeptide. J Virol. 1988;62:802–809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.802-809.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahalingam R, Wellish M, Cohrs R, Debrus S, Piette J, Rentier B, Gilden D H. Expression of protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 in latently infected human ganglionic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2122–2124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLauchlan J, Liefkens K, Stow N D. The herpes simplex virus type 1 UL37 gene product is a component of virus particles. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2047–2052. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-8-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olmsted J B. Analysis of cytoskeletal structures using blot-purified monospecific antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 1986;134:467–472. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)34112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. p. 18.74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitz J B, Albright A G, Kinchington P R, Jenkins F J. The UL37 protein of herpes simplex virus type 1 is associated with the tegument of purified virions. Virology. 1995;206:1055–1065. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelton L, Albright A G, Ruyechan W T, Jenkins F J. Retention of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) UL37 protein on single-stranded DNA columns requires the HSV-1 ICP8 protein. J Virol. 1994;68:521–525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.521-525.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelton L, Pensiero M N, Jenkins F J. Identification and characterization of the herpes simplex virus type 1 protein encoded by the UL37 open reading frame. J Virol. 1990;64:6101–6109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6101-6109.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione-S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somogyi P, Takagi H. A note on the use of picric acid-paraformaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative for correlated light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Neuroscience. 1982;7:1779–1783. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straus S E, Aulakh H S, Ruychan W T, Hay J, Casey T A, Vande Woude G F, Owens J, Smith H A. Structure of varicella virus DNA. J Virol. 1981;40:516–525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.40.2.516-525.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from acrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vafai A, Wroblewska Z, Wellish M, Green M, Gilden D H. Analysis of three late varicella-zoster virus proteins, a 125,000-molecular-weight protein and gp1 and gp3. J Virol. 1984;52:953–959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.953-959.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]