Abstract

BACKGROUND

Frey syndrome, also known as ototemporal nerve syndrome or gustatory sweating syndrome, is one of the most common complications of parotid gland surgery. This condition is characterized by abnormal sensations in the facial skin accompanied by episodes of flushing and sweating triggered by cognitive processes, visual stimuli, or eating.

AIM

To investigate the preventive effect of acellular dermal matrix (ADM) on Frey syndrome after parotid tumor resection and analyzed the effects of Frey syndrome across various surgical methods and other factors involved in parotid tumor resection.

METHODS

Retrospective data from 82 patients were analyzed to assess the correlation between sex, age, resection sample size, operation time, operation mode, ADM usage, and occurrence of postoperative Frey syndrome.

RESULTS

Among the 82 patients, the incidence of Frey syndrome was 56.1%. There were no significant differences in sex, age, or operation time between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, there was a significant difference between ADM implantation and occurrence of Frey syndrome (P < 0.05). ADM application could reduce the variation in the incidence of Frey syndrome across different operation modes.

CONCLUSION

ADM can effectively prevent Frey syndrome and delay its onset.

Keywords: Parotid gland tumor, Frey syndrome, Acellular dermal matrix, Acellular allogenic dermal matrix

Core Tip: The use of acellular dermal matrix in parotid tumor surgery can reduce the incidence of Frey syndrome, especially when the diameter of the surgically removed parotid tissue is greater than 4 cm.

INTRODUCTION

Frey syndrome, also known as ototemporal nerve syndrome or gustatory sweating syndrome, is one of the most common complications of parotid gland surgery. This condition is characterized by abnormal sensations in the facial skin accompanied by episodes of flushing and sweating triggered by cognitive processes, visual stimuli, or eating[1]. This syndrome was first described by Lucie Frey in 1923; however, its precise pathogenesis remains unclear. The incidence rate of Frey syndrome varies greatly, ranging from 4% to 96%[2,3], attributed, in part, to differences in the diagnostic criteria for Frey syndrome[4] and differences in methods[5] and techniques used in parotid gland surgery. The primary therapeutic approach is managing associated symptoms. Notably, some researchers have diagnosed Frey syndrome using a minor test and evaluated its severity. Unfortunately, this diagnostic method only assesses subclinical patients without overt clinical symptoms. This inclusion has inadvertently increased the recorded incidence of Frey syndrome[6-8]. This retrospective study investigated the factors influencing the acellular dermal matrix (ADM) in the prevention of Frey syndrome in patients who have undergone parotid surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research methods

In this retrospective analysis of clinical data from 126 patients who underwent parotid gland surgery in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Anshun People's Hospital between January 2018 and December 2020, a total of 82 patients were deemed eligible for the study. Patients with parotid gland inflammation, patients who had undergone lymph node dissection, and patients who had undergone periparotid gland surgery during the same period were excluded. All patients provided informed consent for both computed tomography examinations and surgeries. Before the use of ADM, patients were informed regarding the manufacturer, safety, cost, and surgical benefits of ADM. The ADM used was the Hiao B-type oral repair membrane produced by Yantai Zhenghai Biological Technology (registration number: 20153460386).

Surgical method

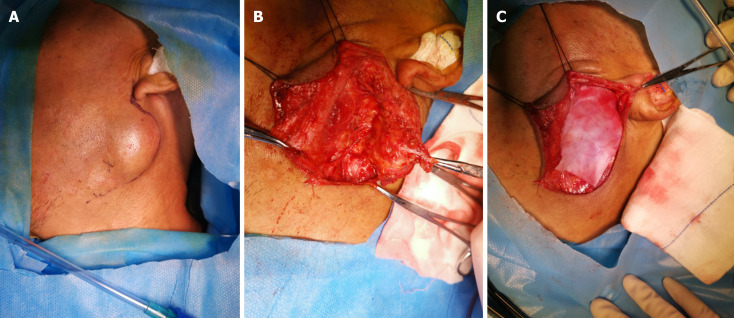

A modified "S" incision[9] was made in the conventional parotid area. The platysma muscle under the skin was incised, the parotid gland envelope was opened, and the envelope was preserved for tumors that did not invade it. The facial nerve was dissected retrogradely, and any tumor-invading segments of the facial nerve were resected. Partial parotid resection or total parotid lobectomy was performed, depending on the size and location of the tumor. The surgical method randomly categorized the patients into either the partial parotid resection group or the total parotid lobectomy group. The patients were randomly divided into a tissue patch implantation group and a control group according to their preoperative informed consent and willingness to undergo tissue patch implantation. After surgery, all patients underwent negative pressure ball drainage; for patients with an implanted tissue patch, the drainage tube was placed above the patch according to the product guidelines (Figure 1). Pressure was applied routinely for 14 d after surgery.

Figure 1.

The drainage tube was placed above the patch according to the product guidelines for patients with an implanted tissue patch. A: Diagram B of the surgical incision; B: For superficial parotid lobectomy behind nerve exposure; C: Acellular dermal matrix after implantation.

Diagnostic criteria for Frey syndrome

Patients were contacted by phone each month after surgery, during which they were questioned regarding symptoms, such as facial flushing, facial paresthesia, and facial sweating during eating. These responses were used to assess Frey syndrome using a subjective questionnaire. Positive Frey syndrome was defined as the presence of any of the four indicators.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25.0) to assess the correlations between age, sex, surgical method, size of surgically removed samples, time of occurrence of postoperative Frey syndrome, and intraoperative application of ADM for the prevention of Frey syndrome. A logistic regression model was established to analyze the risk factors associated with Frey syndrome. Additionally, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to predict the diagnostic value of certain risk factors for Frey syndrome. The significance level for the tests was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Data of patients with Frey syndrome

A total of 82 patients were included in this study, 46 of whom developed Frey syndrome, an incidence rate of 56.1%. Among them, 43 (52.4%) experienced facial paresthesia after eating, 29 (35.4%) experienced facial flushing after eating, 13 (15.9%) exhibited facial sweating after eating, and 4 (4.9%) reported that these symptoms seriously affected their daily lives (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and proportion of patients with different symptoms in the Frey symptoms group, n (%)

|

Symptoms

|

Number and proportion of cases, n = 82

|

| Facial paresthesia after eating | 43 (52.4) |

| Flushed cheeks after eating | 29 (35.4) |

| Facial sweating after eating | 13 (15.9) |

| Feeling that life is severely affected after surgery | 4 (4.9) |

Analysis of related Frey syndrome factors

The 82 patients were categorized into the Frey and non-Frey groups (Table 2). No significant differences were observed in terms of sex, age, or operation time between the two groups. However, a significant difference was noted in the occurrence of Frey symptoms between patients with and without ADM implantation (P = 0.027 and P < 0.05, respectively). Regarding the surgical methods, no significant difference was observed between the Frey and non-Frey groups (P = 0.295); however, there were significant differences in the various surgical approaches without ADM implantation (P = 0.006 and P < 0.05). All 82 patients were followed up for 16 months postoperatively. In the group with ADM implantation, the median time for Frey symptoms onset was 7.54 ± 3.2 months, whereas in the group without ADM implantation, it was 3.43 ± 2.33 months; these differences were significant (P = 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients after parotidectomy

|

Clinical features

|

Frey group (n = 46)

|

Non-Frey group (n = 36)

|

P value

|

| Sex (male) | 26 (56.52%) | 20 (55.56%) | 0.93 |

| Age (yr) | 48.09 ± 14.95 | 47.08 ± 16.31 | 0.97 |

| Surgically removed sample size (maximum diameter, cm) | 3.40 ± 0.97 | 2.878 ± 0.79 | 0.0291 |

| Method of surgery | |||

| ADM implants | |||

| Partial removal of parotid gland | 8 | 9 | 0.295 |

| Complete removal of parotid gland | 3 | 8 | |

| No-implant ADM | |||

| Partial removal of parotid gland | 21 | 18 | 0.0061 |

| Complete removal of parotid gland | 14 | 1 | |

| Procedure time (min) | 198.54 ± 43.87 | 185.97 ± 57.75 | 0.92 |

| Implanted ADM | |||

| Yes | 11 | 17 | 0.0271 |

| No | 35 | 19 | |

| Time of Frey sign occurrence (months) | |||

| Implant ADM | 7.54 ± 3.2 | 0 | 0.0011 |

| Non-implant ADM | 3.43 ± 2.33 | 0 |

Comparison of the time when Frey signs occurred with and without acellular dermal matrix implantation.

ADM: Acellular dermal matrix.

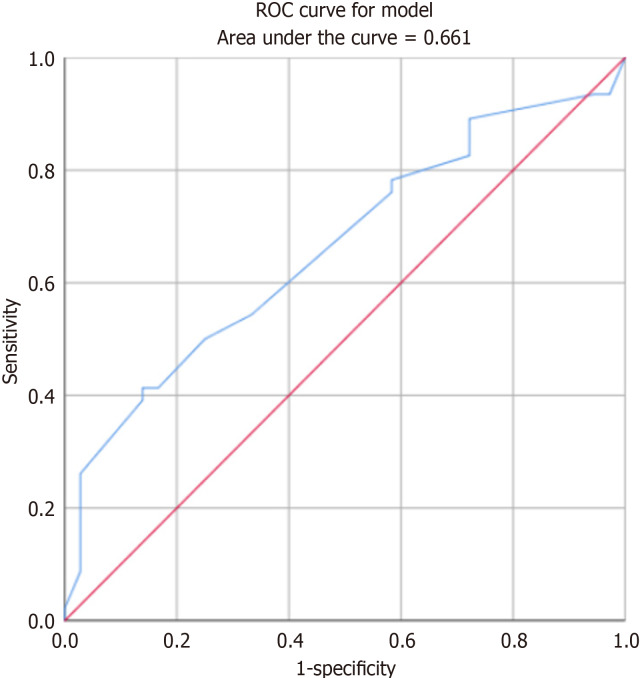

ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the maximum diameter of the surgically resected sample and the occurrence of symptoms of Frey syndrome. The results indicated that the larger the diameter of the resected sample, the higher the probability of Frey syndrome occurrence, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.661 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Diameter of surgically resected sample and receiver operating characteristic curve with Frey sign. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

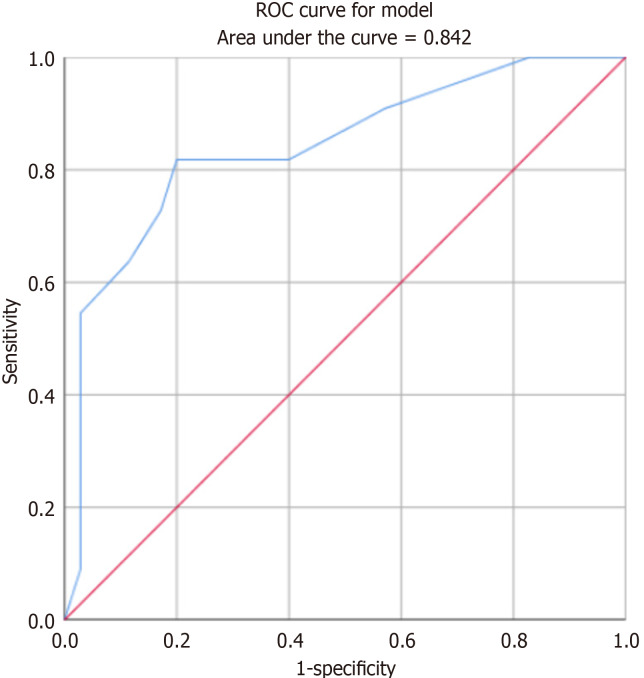

ROC curve analysis comparing the timing of ADM implantation with the timing of the occurrence of symptoms of Frey syndrome revealed that ADM could significantly delay the occurrence of Frey syndrome, with an AUC of 0.842 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frey sign occurrence time and receiver operating characteristic curve after acellular dermal matrix implantation. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

DISCUSSION

Frey syndrome is now commonly believed to be most likely caused by parotid gland surgery or injury. Destruction of parotid gland cyst integrity exposes the parasympathetic branch, which controls the parotid gland acinar secretion in the auriculotemporal nerve issued by the trigeminal nerve within the parotid gland and leads to its misplacement with the sympathetic nerve, which controls the skin sweat glands. Consequently, upon seeing or eating food, an individual’s parasympathetic branch is stimulated, resulting in secretion from skin sweat glands, leading to facial paresthesia, flushing, or sweating[10]. Frey syndrome occurred in 56.1% of the patients in this study, a rate similar to that reported in most studies[11]. ROC analysis of the tumor sample diameter demonstrated that a resected sample with a larger area was correlated with a higher probability of Frey syndrome occurrence (AUC = 0.661). This finding was consistent with the results presented by Lin et al[12]. Therefore, it was concluded that the probability of Frey syndrome increased when the resected tumor diameter exceeded 4 cm[12,13]. ADM can effectively prevent the occurrence of Frey syndrome after resection. Favorable outcomes have been achieved using sternocleidomastoid flap[14] and superficial muscle aponeurotic system flap[15]. For the prevention of Frey syndrome. However, it is important to note that the flap preparation process inevitably prolongs the operation time. In this study, there was no significant difference in operation time between the ADM and non-ADM groups, indicating that this method did not extend the operation time in the context of Frey syndrome prevention. Significant differences in the incidence of Frey syndrome were evident among different surgical methods without ADM. Total parotid excision was more likely to result in Frey syndrome, likely because of the removal of excessive parotid tissue that could potentially damage more ototemporal nerve endings[16]. This can contribute to more dislocation-related complications during nerve injury reconstruction. The use of ADM reduced the variability in the occurrence of Frey syndrome between surgical methods. According to the currently available parotid surgery guidelines[17] for benign tumors, preference is given to extracapsular resection or endoscopic minimally invasive surgery[18,19] to reduce the risk of Frey syndrome. However, in cases of tumors > 4 cm in diameter or located deeper within the parotid gland, total parotid excision combined with ADM[20] to decrease postoperative recurrence and prevent Frey syndrome is recommended.

Regarding the timing of Frey syndrome occurrence, non-implantation of ADM resulted in Frey syndrome occurring approximately 3 months after the operation, consistent with the neural reconstruction theory that the occurrence time for the middle auriculotemporal nerve is abnormal[16]. After ADM implantation, the onset of Frey syndrome was delayed by approximately three months. This delay might be attributed to the severity of the auriculotemporal nerve injury and the absorption timeframe of the ADM.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the application of ADM affects Frey syndrome prevention. However, it is important to note that ADM degrades within approximately six months, and Frey syndrome may still occur after this degradation. Nonetheless, because of the limited number of Frey syndrome cases following ADM implantation in this study, the results may be biased. Additionally, controlling the diameter of the excised samples can help prevent the occurrence of Frey syndrome.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Frey syndrome, also known as ototemporal nerve syndrome or guest-sweating syndrome, is one of the most common complications of parotid gland surgery. It is characterized by abnormal facial skin sensations, flushing, or sweating when the patient thinks, sees, or eats.

Research motivation

This inclusion has inadvertently increased the recorded incidence of Frey syndrome. This retrospective study investigated the factors influencing the acellular dermal matrix (ADM) in the prevention of Frey syndrome in patients who have undergone parotid surgery.

Research objectives

Because of the effects of frey syndrome, there was a need to find a way to reduce its incidence

Research methods

The data of 82 patients were retrospectively analyzed using SPSS 25.0, and the correlations between sex, age, resection sample size, operation time, operation mode, ADM use, and postoperative Frey syndrome were analyzed.

Research results

The incidence of Frey syndrome was 56.1% among the 82 patients. There were no significant differences in sex, age, or operation time between the two groups (P > 0.05). There was a significant difference between ADM implantation and the onset of symptoms of Frey syndrome (P < 0.05). ADM can reduce the variation in Frey syndrome onset. ADM can delay the onset of Frey signs.

Research conclusions

the application of ADM affects Frey syndrome prevention. However, it is important to note that ADM degrades within approximately six months, and Frey syndrome may still occur after this degradation. Additionally, controlling the diameter of the excised samples can help prevent the occurrence of Frey syndrome.

Research perspectives

The incidence of Frey syndrome was reduced by surgery and the implantation of ADM.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Anshun People's Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. 3).

Informed consent statement: The patient provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict-of-interest.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 2, 2023

First decision: January 9, 2024

Article in press: February 25, 2024

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kochurova EV, Russia S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

Contributor Information

Xian-Da Chai, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, People’s Hospital of Anshun, Anshun 561000, Guizhou Province, China.

Huan Jiang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, People’s Hospital of Anshun, Anshun 561000, Guizhou Province, China.

Ling-Ling Tang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, People’s Hospital of Anshun, Anshun 561000, Guizhou Province, China.

Jing Zhang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, People’s Hospital of Anshun, Anshun 561000, Guizhou Province, China.

Long-Fei Yue, Department of General Practice, People’s Hospital of Anshun, Anshun 561000, Guizhou Province, China. longfei_yue@163.com.

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at email lonhfei_yue@163.com. Participants gave informed consent for data.

References

- 1.Mantelakis A, Lafford G, Lee CW, Spencer H, Deval JL, Joshi A. Frey's Syndrome: A Review of Aetiology and Treatment. Cureus. 2021;13:e20107. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guntinas-Lichius O, Gabriel B, Klussmann JP. Risk of facial palsy and severe Frey's syndrome after conservative parotidectomy for benign disease: analysis of 610 operations. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:1104–1109. doi: 10.1080/00016480600672618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder TE, Huber A, Schmid S. Frey's syndrome after parotidectomy: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1496–1501. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi HG, Kwon SY, Won JY, Yoo SW, Lee MG, Kim SW, Park B. Comparisons of Three Indicators for Frey's Syndrome: Subjective Symptoms, Minor's Starch Iodine Test, and Infrared Thermography. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;6:249–253. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2013.6.4.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YC, Liao WC, Yang SW, Luo CM, Tsai YT, Tsai MS, Lee YH, Hsin LJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of modified facelift incision versus modified Blair incision in parotidectomy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:24106. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03483-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuncel A, Karaman M, Sheidaei S, Tatlıpınar A, Esen E. A comparison of incidence of Frey's syndrome diagnosed based on clinical signs and Minor's test after parotis surgery. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2012;22:200–206. doi: 10.5606/kbbihtisas.2012.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann A, Rosenberger D, Vorsprach O, Dazert S. [The incidence of Frey syndrome following parotidectomy: results of a survey and follow-up] HNO. 2011;59:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s00106-010-2223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durgut O, Basut O, Demir UL, Ozmen OA, Kasapoglu F, Coskun H. Association between skin flap thickness and Frey's syndrome in parotid surgery. Head Neck. 2013;35:1781–1786. doi: 10.1002/hed.23233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khafif A, Niddal A, Azoulay O, Holostenco V, Masalha M. Parotidectomy via Individualized Mini-Blair Incision. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2020;82:121–129. doi: 10.1159/000505192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drummond PD. Mechanism of gustatory flushing in Frey's syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2002;12:144–146. doi: 10.1007/s10286-002-0042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motz KM, Kim YJ. Auriculotemporal Syndrome (Frey Syndrome) Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin HJ, Hsiao JR, Chang JS, Hu CL, Chen TR, Lee WT, Huang CC, Ou CY, Tsai SW, Lu YC, Tsai ST, Chao WY, Chang CC. Resected specimen size: A reliable predictor of severe Frey syndrome after parotidectomy. Head Neck. 2019;41:2285–2290. doi: 10.1002/hed.25683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CC, Chan RC, Chan JY. Predictors for Frey Syndrome Development After Parotidectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;79:39–41. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filho WQ, Dedivitis RA, Rapoport A, Guimarães AV. Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap preventing Frey syndrome following parotidectomy. World J Surg. 2004;28:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cristofaro MG, Cordaro R, Barca I, Giudice A. Efficacy of SMAS flap technique to prevent Frey's syndrome and aesthetic outcomes. A retrospective cohort analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2021;92:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bree R, van der Waal I, Leemans CR. Management of Frey syndrome. Head Neck. 2007;29:773–778. doi: 10.1002/hed.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu GY, Ma DQ, Peng X, Wang SL, Li LJ, Yu CQ, Cheng Y. Guidelines On the diagnosis and treatment of salivary gland tumors. Zhonghua Kongqiang Yixue Zazhi. 2010;45:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao L, Liang QL, Ren WH, Li SM, Xue LF, Zhi Y, Song JZ, Wang QB, Dou ZC, Yue J, Zhi KQ. Comparison of endoscope-assisted versus conventional resection of parotid tumors. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57:1003–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou HW, Gao J, Liu JX, Qu ZL, Du ZS, Zhao H, Zhao M, Chen HY. Feasibility and advantages of endoscope-assisted parotidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;59:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, Xu Y, Zhang C, Sun C, Chen Y, Zhao H, Li G, Fan J, Lei D. Modified partial superficial parotidectomy versus conventional superficial parotidectomy improves treatment of pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Am J Surg. 2014;208:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at email lonhfei_yue@163.com. Participants gave informed consent for data.