Abstract

Corrosion of iron‐containing metals under sulfate‐reducing conditions is an economically important problem. Microbial strains now known as Desulfovibrio vulgaris served as the model microbes in many of the foundational studies that developed existing models for the corrosion of iron‐containing metals under sulfate‐reducing conditions. Proposed mechanisms for corrosion by D. vulgaris include: (1) H2 consumption to accelerate the oxidation of Fe0 coupled to the reduction of protons to H2; (2) production of sulfide that combines with ferrous iron to form iron sulfide coatings that promote H2 production; (3) moribund cells release hydrogenases that catalyze Fe0 oxidation with the production of H2; (4) direct electron transfer from Fe0 to cells; and (5) flavins serving as an electron shuttle for electron transfer between Fe0 and cells. The demonstrated possibility of conducting transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of cells growing on metal surfaces suggests that similar studies on D. vulgaris corrosion biofilms can aid in identifying proteins that play an important role in corrosion. Tools for making targeted gene deletions in D. vulgaris are available for functional genetic studies. These approaches, coupled with instrumentation for the detection of low concentrations of H2, and proven techniques for evaluating putative electron shuttle function, are expected to make it possible to determine which of the proposed mechanisms for D. vulgaris corrosion are most important.

Keywords: corrosion, Desulfovibrio, electron shuttle, extracellular electron transfer, Fe0 oxidation, hydrogenase, hydrogen uptake, sulfate reduction, sulfide

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the mechanisms for the corrosion of metals is key to developing strategies for preventing this economically significant problem 1 , 2 . Following the first suggestion that microbes might be important catalysts for the corrosion of metals 3 , 4 , a thorough analysis of the available data led to the conclusion that sulfate‐reducing microorganisms play a key role in iron corrosion 5 . However, in the 1930s, Spirillium desulfuricans was the only microbe known to be capable of sulfate reduction 5 . The genus and species names of this and similar strains of sulfate‐reducing bacteria investigated in corrosion studies have changed over time 6 , 7 , but most are now generally recognized as strains of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Table 1).

Table 1.

Iron corrosion studies with Desulfovibrio vulgaris.

| Year | Straina | Iron source | Lactate | Mechanismb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | Spirillum desulfuricans | CI | + | Ha | 5 |

| 1939 | Vibrio desulfuricans | MS | + | N | 8 |

| 1947 | Vibrio desulfuricans | MS | − | N | 9 |

| 1951 | Vibrio desulfuricans | Armco ingot iron |

+ − |

Ha | 10 |

| 1952 | Vibrio desulfuricans | Armco ingot iron |

+ − |

S | 11 |

| 1960 | D. desulphuricans Hildenborough NCIB 8303 | MS | + | Ha | 12 |

| 1964 | D. desulphuricans Benghazi NCIB 8401 | MS | +? | Ha | 13 |

| America NCIB 8372 | |||||

| Teddington R NCIB 8312 | |||||

| Hildenborough NCIB 8303 | |||||

| Llanelly NCIB 8446 | |||||

| 1968 | D. desulfuricans Teddington R | MS | + | S | 14 |

| 1968 | Hildenborough NICB 8303 | MS | + | Ha | 15 |

| 1971 | D. desulfuricans Teddington R NCIB 8312 | MS |

+ − (+F) |

Hs | 16 |

| 1974 | Hildenborough NCIB 8303 | MS | + | S | 17 |

| 1982 | Isolated from River Thames' sediment | MS (EN2) | + | N | 18 |

| 1986 | Hildenborough NCIB 8303 | MS | − (+A) | Ha | 19 |

| 1986 | Marburg DSM 2119 (Postgate and Campbell) | Steel |

+ − (+A) |

Ha | 20 |

| 1986 | Madison | MS | − (+F) | Ha | 21 |

| 1990 | Hildenborough NCIB 8303 | MS | + | Ha | 22 |

| 1991 | DSM 1744 (Postgate and Campbell) | SS (AISI 3161) | − | N | 23 |

| 1991 | Not specified | Iron (99%) SS (Fe–15Cr–10Ni) | + | Hs | 24 |

| 1991 | Not specified | SS (410) | + | S | 25 |

| 1991 | Isolated from cutting oil emulsions | CS (SAE 1020) | + | N | 26 |

| 1992 | Woolwich NCIMB 8457 | MS (BS970) | + | N | 27 |

| 1993 | NCIB 8303 | Iron | + | N | 28 |

| (Postgate and Campbell) | CS (SAE 1090) | ||||

| (Hildenborough) | SS (18‐8) | ||||

| (DSM 644) | |||||

| 1994 | Not specified | CS (X52) | − | N | 29 |

| 1995 | Isolated from cutting oil emulsions | MS | + | N | 30 |

| 1995 | Not specified | SS (304) | + | N | 31 |

| 1995 | ATCC 25979 | SS (304) | + | N | 32 |

| 1997 | Not specified | SS (AISI 304L) | + | N | 33 |

| 1997 | Not specified | SS (316L) | + | N | 34 |

| 1999 | ATCC 29579 | MS (SAE 1018) | + | N | 35 |

| (Postgate and Campbell) | SS 304 | ||||

| (Hildenborough) | |||||

| (NCIB 8303, DSM 644) | |||||

| 2002 | LMG 7563 | MS | + | N | 36 |

| 2004 | Not specified | Iron | − (+A) | D | 37 |

| 2004 | ATCC 29579 | MS (1010) | + | N | 38 |

| 2007 | DSM 664 | MS (BST 503‐2) | + | N | 39 |

| 2008 | Hildenborough NCIMB 8303 | CS (ASTM A366) |

+ − (+A) |

Ha | 40 |

| 2008 | Isolated from an oil field separator | MS (AISI 1018) | − | N | 41 |

| 2008 | DSMZ 644 | Iron | + | N | 42 |

| CS (ST 37) | |||||

| SS (304) | |||||

| 2010 | DSMZ 644 | Alloyed steel (1.4301, UNS 304) | + | N | 43 |

| 2013 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | N | 44 |

| (Postgate and Campbell) | |||||

| (C‐6, CT1, IFO 13699, NCIB 8372) | |||||

| 2014 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | N | 45 |

| 2014 | ATCC 7757 | CS (X70) | + | N | 46 |

| 2014 | ATCC 7757 | CS (API5L X‐70) | + | N | 47 |

| 2014 | ATCC 7757 | CS (API5L‐X70) | + | N | 48 |

| 2015 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | F | 49 |

| 2015 | ATCC 7757 | SS (304) | + | F | 50 |

| 2016 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | N | 51 |

| 2016 | ATCC 7757 | CS (UNS G10100) | + | N | 52 |

| 2016 | Hildenborough DSM 644 | MS (BST 503‐2) | + | N | 53 |

| 2017 | Not specified | CI | + | N | 54 |

| 2017 | ATCC 7757 | MS | + | N | 55 |

| 2017 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | N | 56 |

| 2018 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | S | 57 |

| 2019 | Not specified | CS (1018) | + | N | 58 |

| 2019 | ATCC 7757 | CS (1018) | + | N | 59 |

| 2019 | ATCC 7757 | PS (X80) | + | N | 59 |

| 2020 | Hildenborough | CS (1030) | + | N | 60 |

| 2020 | ATCC 7757 | SS (2205) | + | N | 61 |

| 2020 | Hildenborough | CS | + | N | 62 |

| 2020 | ATCC 7757 | CS (X65) | + | F | 63 |

| 2021 | ATCC 7757 | GS | + | N | 64 |

| 2021 | ATCC 7757 | SS (410, 420, 316, 2206) | + | N | 65 |

| 2021 | ATCC 7757 | CS (C1018) | + | N | 66 |

| 2021 | ATCC 7757 | SS (2205) | + | N | 67 |

| 2021 | ATCC 7757 | SS (2205) | + | N | 68 |

Strains now considered to be Desulfovibrio vulgaris were previously designated as Spirillium desulfuricans, Vibrio desulfuricans, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, and Desulfovibrio desulphuricans 6 , 7 . Therefore, microbes that were later renamed D. vulgaris are listed by the name designated in the original text. Only strain designations are listed for strains designated as D. vulgaris in the original text. Alternative designations for these strains are described in parentheses.

Primary corrosion mechanism discussed. Ha, abiotic H2 production from iron; Hs, H2 production from iron‐catalyzed by FeS mineral deposits; S, sulfide promoting iron corrosion; D, direct electron transfer; F, electron transfer with a flavin shuttle; N, not applicable (the studies focused on biofilm formation, growth inhibition, corrosion inhibition, etc.). +, lactate included; −, no lactate; − (+A), no lactate but acetate added; − (+F), cells grown on fumarate; CI, cast iron; CS, carbon steel; GS, galvanized steel; MS, mild steel; PP, pipeline steel; SS, stainless steel.

There is substantial evidence that Desulfovibrio species are involved in the corrosion of iron‐containing metals in anaerobic environments 69 , 70 . Desulfovibrio species were abundant within the microbial community on metal surfaces exposed to oil field production waters 71 , 72 , corroded oil pipelines 73 , corroding steel pipe carrying oily seawater 74 , rust layers on steel plates immersed in seawater 75 , and the inner rust layer on carbon steel 76 . Desulfovibrio species were recovered in culture from corrosion sites 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , including a D. vulgaris strain isolated from an oil field separator in the Gulf of Mexico that was damaged by corrosion 41 . Microbial activity on the cathodes of bioelectrochemical systems is thought to be related to microbial corrosion 81 and Desulfovibrio species are often enriched on cathodes from diverse microbial communities 82 , 83 , 84 .

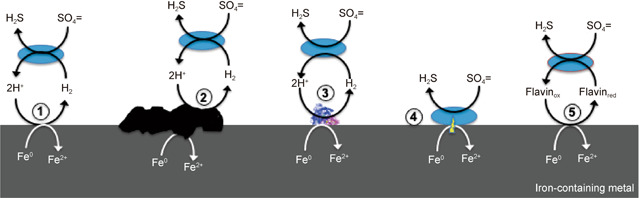

Several mechanisms for D. vulgaris corrosion of iron‐containing metals have been proposed (Figure 1). These mechanisms may not be mutually exclusive. As detailed in this review, each of these models still requires rigorous examination. However, with the increasing availability of molecular tools to probe microbial activity and tools for genetic manipulation of D. vulgaris 85 , 86 , it now may be the time to either eliminate or confirm some of the existing mechanistic models for D. vulgaris corrosion or to develop new models. The purpose of this review is to summarize the previously proposed routes for Desulfovibrio species iron corrosion and to suggest experimental approaches to further advance the understanding of corrosion by this popular model microbe.

Figure 1.

Previously proposed mechanisms for Desulfovibrio vulgaris to promote the corrosion of iron‐containing metals. These include the consumption of abiotically produced H2 (1); consumption of H2 generated via catalysis by FeS (2) or hydrogenase (3); direct electron transfer from Fe0 to cells via outer‐surface electron transport components on the cell surface (4); and Fe0 oxidation via reduction of the oxidized form of soluble flavin electron shuttle (Flavinox) with reduced flavin (Flavinred) serving as the electron donor for sulfate reduction (5). The studies proposing these mechanisms are cited in the main text.

IRON CORROSION VIA AN H2 INTERMEDIATE

The corrosion of iron‐containing metals results from the oxidation of metallic iron to ferrous iron:

| (1) |

As recognized in the early analysis of corrosion by sulfate reducers 5 , protons are a likely electron acceptor for the electrons derived from Fe0. In early studies, the product of proton reduction is often referred to as “metallic hydrogen,” but in the absence of data demonstrating that this form of hydrogen exists on the surface of corroding iron or can serve as an electron donor for microbial respiration, we assume that proton reduction yields H2, a known electron donor for diverse microbes:

| (2) |

H2 is an electron donor for D. vulgaris:

| (3) |

and growth on H2 is possible if acetate is provided as a carbon source 87 .

Substantial abiotic H2 production from Fe0 was discounted in the early version of the model in which H2 serves as an electron carrier between Fe0 and cells 5 . However, the mechanism by which cells promoted the oxidation of Fe0 with the production of H2 was not specified. It is now known that the extent of abiotic H2 production depends upon the form of the iron‐containing metal. For example, pure Fe0 abiotically produces substantial H2 when submerged in anoxic water at circumneutral pH whereas 316 stainless steel does not 88 , 89 .

This difference in H2 production between Fe0 and stainless steel could provide one method for evaluating whether D. vulgaris relies on H2 production to consume electrons from iron‐containing metals. The closely related sulfate reducer D. ferrophilus reduced sulfate when pure Fe0 was the electron donor, but not in a medium with stainless steel 90 . In contrast, Geobacter species capable of direct electron uptake could use either iron form as an electron donor 88 , 89 , 90 . These results indicated that D. ferrophilus was incapable of direct electron uptake and required the production of H2 to mediate electron transfer between Fe0 and cells.

The most direct approach to evaluating whether H2 is an important intermediate in electron uptake from extracellular electron donors may be to generate a mutant that is unable to consume H2 91 . D. vulgaris Hildenborough has multiple hydrogenases that have different localizations and metal constituents: the periplasmic [NiFe] HynAB‐1 and HynAB‐2, the periplasmic [Fe] HydAB, the periplasmic [NiFeSe] HysAB, the cytoplasmic [Fe] HydC, and the cytoplasmic membrane‐bound Coo and Ech hydrogenases 92 . Deletions of genes for HydAB, HynAB‐1, or HysAB negatively impacted the growth of D. vulgaris Hildenborough with H2 as the electron donor 93 , 94 , 95 . However, these single‐gene deletion mutants and a double deletion mutant of HynAB‐1 and HydAB 95 still grew on H2 as the electron donor, indicating redundant, complementary functions of the multiple hydrogenases. Thus, the construction of a strain with multiple hydrogenase gene deletions may be required to rigorously evaluate the role of H2 in corrosion.

Transcriptomic analysis comparing growth on H2 supplied from proton reduction with an iron electrode poised at −1.1 V versus growth on H2 simply bubbled into medium revealed that the genes for HynAB‐1 and HydAB were more highly expressed during growth on the cathodic H2 40 . Gene transcripts for HysAB were more abundant when H2 was bubbled into the medium. Gene deletions that prevented the function of the HynAB‐1 and HydAB hydrogenases inhibited electron uptake from the iron cathodes 40 , as might be expected for cathodes poised at a low potential to induce H2 production. The impact of the hydrogenase gene deletions on corrosion of iron that was not artificially poised at a negative potential was not determined because wild‐type cells could not be grown under these conditions 40 . Lack of growth on unpoised iron suggests an inability to use Fe0 as an electron donor. This difference between artificially poised iron cathodes and unpoised iron metal is an important consideration when evaluating other studies 19 that have concluded that H2 is an important intermediate in iron corrosion by D. vulgaris based on experiments with electrochemically poised iron electrodes.

However, there is some indirect evidence for H2 serving as an intermediary electron carrier between Fe0 and D. vulgaris, especially when H2 is not the sole electron donor. D. vulgaris did not reduce sulfate when steel wool was provided as the sole electron donor, but when lactate was added as an additional electron donor, more sulfide was produced than was possible from lactate oxidation alone 20 . In contrast, D. sapovorans, which cannot utilize H2, did not produce substantially more sulfide when grown in the presence of lactate and steel wool, than when grown with lactate alone. These results suggested that H2 was an intermediary electron carrier for D. vulgaris electron uptake from the steel wool during growth with lactate 20 . The expression of one or more uptake hydrogenases is expected to be upregulated when H2 is serving as an electron donor 96 , 97 , 98 . Thus, transcriptional and/or proteomic studies may be useful in further assessing the role of H2 as an electron donor during corrosion in the presence of lactate. Additional indirect evidence for the importance of H2 as an electron carrier was the finding that D. vulgaris corroded “mild steel” faster than the gram‐positive D. orientis, which cannot consume H2 12 , 13 .

Other early studies suggested that H2 production from iron was not a mechanism for corrosion 10 , 11 . However, the medium for investigating the possibility for H2 serving as an electron donor did not include acetate, which is required as a carbon source for growth on H2. Therefore, no conclusion on the role of H2 is possible from those studies.

FACTORS PROMOTING H2 PRODUCTION

In a diversity of microbes, hydrogenases released from lysed cells, or specifically transported to the outer surface of living cells, facilitate the production of H2 from Fe0 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 . For example, methanogens highly effective in corrosion can produce an extracellular hydrogenase that enhances H2 production from Fe0 99 . Such extracellular hydrogenases have not been reported in Desulfovibrio species, but moribund cells of D. vulgaris release periplasmic hydrogenases that can retain activity for months 103 . Subjecting D. vulgaris to starvation, a condition likely to promote cell death and lysis, enhanced corrosion 45 , 58 . Therefore, studies to evaluate the role of extracellular hydrogenases in corrosion by D. vulgaris are warranted.

The iron sulfide that precipitates on iron‐containing metals during corrosion coupled to sulfate reduction may also increase H2 production. The addition of FeS reduced the overpotential necessary to produce H2 from iron cathodes, suggesting a role for FeS in promoting the formation of H2 16 . In studies in which the culture was grown on fumarate rather than via sulfate reduction, the current was generated at more positive potentials when FeS was deposited on either mild steel or platinum cathodes 14 . These results further indicate that FeS may serve as a catalyst for H2 generation. However, in studies with carbon steel coupons, it appeared that higher accumulations of sulfide inhibited corrosion 57 . The ability of D. vulgaris to corrode steel with either benzyl viologen as the electron acceptor 15 or when growing on fumarate 21 demonstrated that sulfide production was not essential for corrosion. Thus, a clear‐cut concept for the role of FeS in corrosion has yet to be established.

Technology for measuring H2 concentrations at extremely low concentrations during corrosion is available 89 . Thus, with the appropriate H2 detector it should be possible to directly evaluate the role of FeS in facilitating H2 production from iron‐containing metals, simply by monitoring H2 generation in the presence or absence of different quantities of FeS precipitate.

ELECTRON SHUTTLES OTHER THAN H2

Soluble redox‐active molecules promote extracellular electron exchange between microbes and minerals, electrodes, and other microbial species 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 . These electron shuttles typically accelerate extracellular electron exchange by alleviating the need for outer‐surface electron transfer components to establish direct electrical contact with particulate extracellular donors and acceptors. The addition of riboflavin and flavin adenine dinucleotide enhanced D. vulgaris corrosion of carbon steel and stainless steel 49 , 50 , 63 . However, amendments of these cofactors, which are important for the function of numerous proteins, could influence D. vulgaris growth and metabolism in many ways. To determine whether flavins can serve as an electron shuttle for the corrosion of iron‐containing metals coupled to sulfate reduction it is necessary to demonstrate that: (1) the metals are capable of reducing the flavins; and (2) that the reduced flavins can serve as electron donors for sulfate reduction.

DIRECT ELECTRON UPTAKE

Direct electron uptake from iron‐containing metals has been demonstrated with Geobacter sulfurreducens and Geobacter metallireducens 88 , 89 , 90 . Strains unable to utilize H2 readily reduced fumarate, nitrate, or Fe(III) with pure Fe0 or stainless steel as the electron donor. Deletion of genes for outer‐surface, multiheme c‐type cytochromes previously shown to be involved in electron exchange with other extracellular donors/acceptors inhibited the corrosion.

There are no examples of similar studies with sulfate‐reducing microorganisms. It was suggested that c‐type cytochromes positioned in the outer membrane of D. vulgaris might be able to make an electrical connection with Fe0 108 . However, subsequent studies have indicated that D. vulgaris does not have outer‐surface cytochromes 92 . Clear next steps in this line of investigation would be to rigorously verify whether cytochromes are exposed on the outer surface of D. vulgaris, and if so, evaluate their role in iron corrosion with the appropriate gene deletion studies. Genetic, biochemical, biophysical, and immunological approaches previously employed for investigating the location and function of the outer‐surface cytochromes of Geobacter would be suitable 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 .

Although it has been suggested that several of the c‐type cytochromes of D. ferrophilus may be localized in the outer membrane, no genetic studies have been conducted to determine whether they are involved in extracellular electron exchange 90 , 113 , 114 , 115 . As noted above, experimental analysis of iron corrosion by D. ferrophilus has suggested that it relies on H2 as an intermediary electron carrier rather than direct electron uptake 90 .

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Sulfate‐reducing microorganisms are considered to be important agents for catalyzing the corrosion of iron‐containing metals and D. vulgaris has historically been the model microbe of choice for elucidating the mechanisms for corrosion by sulfate reducers. As summarized above (Figure 1), previous studies have suggested several mechanisms by which D. vulgaris may enhance corrosion, but each of the proposed mechanisms requires further experimental evaluation. The mechanisms for electron transfer between iron‐containing metals and Geobacter species were elucidated with genome‐scale transcriptomics coupled with phenotypic analysis of mutant strains in which the genes for proteins hypothesized to be involved in electron transfer were deleted 88 , 89 . Deletion of the genes for hydrogenases and hypothesized outer‐surface electrical contacts made it possible to determine the role of H2 as an intermediary electron carrier and to identify likely electrical contacts on the outer surface of the cell. A similar approach seems possible for the study of D. vulgaris corrosion mechanisms. Transcriptomics of D. vulgaris biofilms is possible 39 , 40 to aid in identifying components that may have increased expression during corrosion of iron‐containing metals versus other growth modes. Other candidates for corrosion components may be identified from the known physiological roles of proteins or their cellular location. Methods for the targeted deletion of genes in D. vulgaris are available 85 , 86 making it possible to evaluate the function of proteins hypothesized to be of importance. In fact, an extensive library of D. vulgaris mutants is publicly available, potentially eliminating the substantial investment of time and resources required for mutant construction 86 . Comparison of corrosion capabilities with Fe0, which readily reduces protons to generate H2, versus stainless steel, which does not generate H2, provides an additional tool to evaluate the role of H2 as an intermediary electron carrier for corrosion 89 , 90 . Mechanisms for the corrosion of carbon steel, the most common form of iron in structural materials, should also be investigated. The hypothesis that FeS deposits stimulate H2 production from iron‐containing metals should be readily addressable with highly sensitive H2 detection systems 88 , 89 . Mechanistic and genetic 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 approaches for the study of the role of electron shuttles in electron transfer to minerals and electrodes should be applicable to the study of the role of flavins as electron shuttles for corrosion. Therefore, it is expected that D. vulgaris will continue to serve as an important model microbe for the further elucidation of mechanisms for corrosion under sulfate‐reducing conditions.

Ueki T, Lovley DR. Desulfovibrio vulgaris as a model microbe for the study of corrosion under sulfate‐reducing conditions. mLife. 2022;1:13–20. 10.1002/mlf2.12018

Edited by Hailiang Dong, Miami University, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Procópio L. The era of ‘omics’ technologies in the study of microbiologically influenced corrosion. Biotechnol Lett. 2020;42:341–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lekbach Y, Liu T, Li Y, Moradi M, Dou W, Xu D, et al. Microbial corrosion of metals: the corrosion microbiome. Adv Microb Physiol. 2021;78:317–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garrett JH. The action of water on lead, H K Lewis, London; 1891. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaines R. Bacterial activity as a corrosive influence in the soil. J Ind Eng Chem. 1910;2:128–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5. von Wolzoge Kühr CAH, van der Vlugt LS. The graphitization of cast iron as an electrobiochemical process in anaerobic soil. Water. 1934;18:147–65. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller JDA, Tiller AK. Microbial corrosion of buried and immersed metal. In: Miller JDA, editor. Microbial aspects of metallurgy. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1970. p. 61–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iverson WP. Microbial corrosion of iron. In: Neilands JB, editor. Microbial iron metabolism. New York, NY: Elsevier; 1974. p. 475–513. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bunker HJ. Microbiological experiments in anaerobic corrosion. J Soc Chem Ind. 1939;58:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Butlin KR, Adams ME. Autotrophic growth of sulphate‐reducing bacteria. Nature. 1947;160:154–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spruit CJP, Wanklyn JN. Iron/sulphide ratios in corrosion by sulphate‐reducing bacteria. Nature. 1951;168:951–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wanklyn JN, Spruit CJP. Influence of sulphate‐reducing bacteria on the corrosion potential of iron. Nature. 1952;169:928–9.14941089 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Booth GH, Tiller AK. Polarization studies of mild steel in cultures of sulphate‐reducing bacteria. Trans Faraday Soc. 1960;56:1689–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Booth GH. Sulphur bacteria in relation to corrosion. J Appl Bacteriol. 1964;27:174–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Booth GH, Elford L, Wakerley DS. Corrosion of mild steel by sulphate‐reducing bacteria: an alternative mechanism. Br Corros J. 1968;3:242–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Booth GH, Tiller AK. Cathodic characteristics of mild steel in suspensions of sulphate‐reducing bacteria. Corros Sci. 1968;8:583–600. [Google Scholar]

- 16. King RA, Miller JDA. Corrosion by the sulphate‐reducing bacteria. Nature. 1971;233:491–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Costello JA. Cathodic depolarization by sulphate‐reducing bacteria. S Afr J Sci. 1974;70:202–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaylarde CC, Johnston JM. The effect of Vibrio anguillarum on anaerobic metal corrosion induced by Desulfovibrio vulgaris . Internat Biodet Bull. 1982;18:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pankhania IP, Moosavi AN, Hamilton WA. Utilization of cathodic hydrogen by Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough). J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:3357–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cord‐Ruwisch R, Widdel F. Corroding iron as a hydrogen source for sulfate reduction in growing cultures of sulfate‐reducing bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;25:169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tomei FA, Mitchell R. Development of an alternative method for studying the role of H2‐consuming bacteria in the anaerobic oxidation of iron. Proceedings of International Conference on Biologically Induced Corrosion. National Association of Corrosion Engineers, Houston, TX. 1986. p. 309–20.

- 22. Czechowski MH, Chatelus C, Fauque G, Libert‐Coquempot MF, Lespinat PA, Berlier Y, et al. Utilization of cathodically‐produced hydrogen from mild steel by Desulfovibrio species with different types of hydrogenases. J Ind Microbiol. 1990;6:227–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benbouzld‐Rollet ND, Conte M, Guezennec J, Prieur D. Monitoring of a Vibrio natriegens and Desulfovibrio vulgaris marine aerobic biofilm on a stainless steel surface in a laboratory tubular flow system. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;71:244–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Newman RC, Webster BJ, Kelly RG. The electrochemistry of SRB corrosion and related inorganic phenomena. ISIJ Int. 1991;31:201–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moreno DA, de Mele MFL, Ibars JR, Videla HA. Influence of microstructure on the electrochemical behavior of type 410 stainless steel in chloride media with inorganic and biogenic sulfide. Corrosion. 1991;47:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gomez de Saravia SG, Guiamet PS, de Mele MFL, Videla HA. Biofilm effects and MIC of carbon steel in electrolytic media contaminated with microbial strains isolated from cutting‐oil emulsions. Corrosion. 1991;47:687–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaylarde CC. Sulfate‐reducing bacteria which do not induce accelerated corrosion. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 1992;30:331–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geiger SL, Ross TJ, Barton LL. Environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) evaluation of crystal and plaque formation associated with biocorrosion. Microsc Res Tech. 1993;25:429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guezennec JG. Cathodic protection and microbially induced corrosion. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 1994;34:275–88. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dubey RS, Namboodhiri TKG, Upadhyay SN. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of mild steel in cultures of sulphate reducing bacteria. Indian J Chem Technol. 1995;2:327–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Angell P, White DC. Is metabolic activity by biofilms with sulfate‐reducing bacterial consortia essential for long‐term propagation of pitting corrosion of stainless steel? J Ind Microbiol. 1995;15:329–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Angell P, Luo J‐S, White DC. Microbially sustained pitting corrosion of 304 stainless steel in anaerobic seawater. Corros Sci. 1995;37:1085–96. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gómez de Saravia SG, de Mele MFL, Videla HA, Edyvean RGJ. Bacterial biofilms on cathodically protected stainless steel. Biofouling. 1997;11:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Angell P, Machowski WJ, Paul PP, Wall CM, Lyle FF Jr. A multiple chemostat system for consortia studies on microbially influenced corrosion. J Microbiol Methods. 1997;30:173–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jayaraman A, Hallock PJ, Carson RM, Lee C‐C, Mansfeld FB, Wood TK. Inhibiting sulfate‐reducing bacteria in bioflms on steel with antimicrobial peptides generated in situ. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;52:267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McLeod ES, MacDonald R, Brözel VS. Distribution of Shewanella putrefaciens and Desulfovibrio vulgaris in sulphidogenic biofilms of industrial cooling water systems determined by fluorescent in situ hybridisation. Water SA. 2002;28:123–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dinh HT, Kuever J, Mussmann M, Hassel AW, Stratmann M, Widdel F. Iron corrosion by novel anaerobic microorganisms. Nature. 2004;427:829–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zuo R, Ornek D, Syrett BC, Green RM, Hsu C‐H, Mansfeld FB, et al. Inhibiting mild steel corrosion from sulfate‐reducing bacteria using antimicrobial‐producing biofilms in Three‐Mile‐Island process water. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64:275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang W, Culley DE, Nie L, Scholten JCM. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Desulfovibrio vulgaris grown in planktonic culture and mature biofilm on a steel surface. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:447–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Caffrey SM, Park HS, Been J, Gordon P, Sensen CW, Voordouw G. Gene expression by the sulfate‐reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough grown on an iron electrode under cathodic protection conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. González‐Rodríguez CA, Rodríguez‐Gómez FJ, Genescá‐Llongueras J. The influence of Desulfovibrio vulgaris on the efficiency of imidazoline as a corrosion inhibitor on low‐carbon steel in seawater. Electrochim Acta. 2008;54:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stadler R, Fuerbeth W, Harneit K, Grooters M, Woelbrink M, Sand W. First evaluation of the applicability of microbial extracellular polymeric substances for corrosion protection of metal substrates. Electrochim Acta. 2008;54:91–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stadler R, Wei L, Fürbeth W, Grooters M, Kuklinski A. Infuence of bacterial exopolymers on cell adhesion of Desulfovibrio vulgaris on high alloyed steel: corrosion inhibition by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Mater Corros. 2010;61:1008–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu D, Li Y, Gu T. D‐Methionine as a biofm dispersal signaling molecule enhanced tetrakis hydroxymethyl phosphonium sulfate mitigation of Desulfovibrio vulgaris bioflm and biocorrosion pitting. Mater Corros. 2013;65:837–45. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu D, Gu T. Carbon source starvation triggered more aggressive corrosion against carbon steel by the Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm. Int Biodeter Biodegr. 2014;91:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abu Bakar A, Noor N, Yahaya N, Mohd Rasol R, Fahmy MK, Fariza SN. Disinfection of sulphate reducing bacteria using ultraviolet treatment to mitigate microbial induced corrosion. J Biol Sci. 2014;14:349–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abdullah A, Yahaya N, Noor NM, Rasol RM. Microbial corrosion of API 5L X‐70 carbon steel by ATCC 7757 and consortium of sulfate‐reducing bacteria. J Chem. 2014;2014:130345–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rasol RM, Yahaya N, Noor NM, Abdullah A, Rashid ASA. Mitigation of sulfate‐reducing bacteria (SRB), Desulfovibrio vulgaris using low frequency ultrasound radiation. J Corros Sci Eng. 2014;17:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li H, Xu D, Li Y, Feng H, Liu Z, Li X, et al. Extracellular electron transfer is a bottleneck in the microbiologically influenced corrosion of C1018 carbon steel by the biofilm of sulfate‐reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris . PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang P, Xu D, Li Y, Yang K, Gu T. Electron mediators accelerate the microbiologically influenced corrosion of 304 stainless steel by the Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm. Bioelectrochemistry. 2015;101:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li Y, Zhang P, Cai W, Rosenblatt JS, Raad II, Xu D, et al. Glyceryl trinitrate and caprylic acid for the mitigation of the Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm on C1018 carbon steel. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen Y, Torres J, Castaneda H, Ju L‐K. Quantitative comparison of anaerobic pitting patterns and damage risks by chloride versus Desulfovibrio vulgaris using a fast pitting‐characterization method. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 2016;109:119–31. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y, Pei G, Chen L, Zhang W. Metabolic dynamics of Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm grown on a steel surface. Biofouling. 2016;32:725–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Batmanghelich F, Li L, Seo Y. Influence of multispecies biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Desulfovibrio vulgaris on the corrosion of cast iron. Corros Sci. 2017;121:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nwankwo HU, Olasunkanmi LO, Ebenso EE. Experimental, quantum chemical and molecular dynamic simulations studies on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by some carbazole derivatives. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jia R, Li YD, Xu Y, Gu D. T. Mitigation of the Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm using alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride enhanced by D‐amino acids. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 2017;117:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jia R, Tan JL, Jin P, Blackwood DJ, Xu D, Gu T. Effects of biogenic H2S on the microbiologically influenced corrosion of C1018 carbon steel by sulfate reducing Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm. Corros Sci. 2018;130:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dou W, Liu J, Cai W, Wang D, Jia R, Chen S, et al. Electrochemical investigation of increased carbon steel corrosion via extracellular electron transfer by a sulfate reducing bacterium under carbon source starvation. Corros Sci. 2019;150:258–67. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sun YP, Yang CT, Yang CG, Xu DK, Li Q, Yin L, et al. Stern–Geary constant for X80 pipeline steel in the presence of different corrosive microorganisms. Acta Metall Sin. 2019;32:1483–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Scarascia G, Lehmann R, Machuca LL, Morris C, Cheng KY, Kaksonen A, et al. Effect of quorum sensing on the ability of Desulfovibrio vulgaris to form biofilms and to biocorrode carbon steel in saline conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86:e01664–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thuy TTT, Kannoorpatti K, Padovan A, Thennadil S. Effect of alkaline artificial seawater environment on the corrosion behaviour of duplex stainless steel 2205. Appl Sci. 2020;10:5043. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shiibashi M, Deng X, Miran W, Okamoto A. Mechanism of anaerobic microbial corrosion suppression by mild negative cathodic polarization on carbon steel. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7:690–4. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang D, Liu J, Jia R, Dou W, Kumseranee S, Punpruk S, et al. Distinguishing two different microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) mechanisms using an electron mediator and hydrogen evolution detection. Corros Sci. 2020;177:108993. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang D, Unsal T, Kumseranee S, Punpruk S, Mohamed ME, Saleh MA, et al. Sulfate reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris caused severe microbiologically influenced corrosion of zinc and galvanized steel. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 2021;157:105160. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tran TTT, Kannoorpatti K, Padovan A, Thennadil S. A study of bacteria adhesion and microbial corrosion on different stainless steels in environment containing Desulfovibrio vulgaris . R Soc Open Sci. 2021;8:201577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Unsal T, Wang D, Kumseranee S, Punpruk S, Gu T. D‐tyrosine enhancement of microbiocide mitigation of carbon steel corrosion by a sulfate reducing bacterium biofilm. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;37:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tran TTT, Kannoorpatti K, Padovan A, Thennadil S. Effect of pH regulation by sulfate‐reducing bacteria on corrosion behaviour of duplex stainless steel 2205 in acidic artificial seawater. R Soc Open Sci. 2021;8:200639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tran TTT, Kannoorpatti K, Padovan A, Thennadil S, Nguyen K. Microbial corrosion of DSS 2205 in an acidic chloride environment under continuous flow. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hamilton WA. Sulphate‐reducing bacteria and anaerobic corrosion. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:195–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Beech IB, Sunner JA. Sulphate‐reducing bacteria and their role in corrosion of ferrous materials. In: Barton LL, Hamilton WA, editors. Sulfate‐reducing bacteria: environmental and engineered systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 459–82. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Voordouw G, Shen Y, Harrington CS, Telang AJ, Jack TR, Westlake DWS. Quantitative reverse sample genome probing of microbial communities and its application to oil field production waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li XX, Yang T, Mbadinga SM, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Gu JD, et al. Responses of microbial community composition to temperature gradient and carbon steel corrosion in production water of petroleum reservoir. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Neria‐González I, Wang ET, Ramírez F, Romero JM, Hernández‐Rodríguez C. Characterization of bacterial community associated to biofilms of corroded oil pipelines from the southeast of Mexico. Anaerobe. 2006;12:122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vigneron A, Alsop EB, Chambers B, Lomans BP, Head IM, Tsesmetzis N. Complementary microorganisms in highly corrosive biofilms from an offshore oil production facility. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:2545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li X, Duan J, Xiao H, Li Y, Liu H, Guan F, et al. Analysis of bacterial community composition of corroded steel immersed in Sanya and Xiamen seawaters in China via method of Illumina MiSeq sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang Y, Ma Y, Duan J, Li X, Wang J, Hou B. Analysis of marine microbial communities colonizing various metallic materials and rust layers. Biofouling. 2019;35:429–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Feio MJ, Beech IB, Carepo M, Lopes JM, Cheung CW, Franco R, et al. Isolation and characterisation of a novel sulphate‐reducing bacterium of the Desulfovibrio genus. Anaerobe. 1998;4:117–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miranda E, Bethencourt M, Botana FJ, Cano MJ, Sánchez‐Amaya JM, Corzo A, et al. Biocorrosion of carbon steel alloys by an hydrogenotrophic sulfate‐reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio capillatus isolated from a Mexican oil field separator. Corros Sci. 2006;48:2417–31. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tarasov AL, Borzenkov IA. Sulfate‐reducing bacteria of the genus Desulfovibrio from south Vietnam seacoast. Microbiology. 2015;84:553–60.27169244 [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zarasvand KA, Rai VR. Identification of the traditional and non‐traditional sulfate‐reducing bacteria associated with corroded ship hull. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kim BH, Lim SS, Daud WRW, Gadd GM, Chang IS. The biocathode of microbial electrochemical systems and microbially‐influenced corrosion. Bioresour Technol. 2015;190:395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Croese E, Pereira MA, Euverink G‐JW, Stams AJM, Geelhoed JS. Analysis of the microbial community of the biocathode of a hydrogen‐producing microbial electrolysis cell. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92:1083–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pisciotta JM, Zaybak Z, Call DF, Nam J‐Y, Logan BE. Enrichment of microbial electrolysis cell biocathodes from sediment microbial fuel cell bioanodes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5212–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jafary T, Yeneneh AM, Daud WRW, Al Attar MSS, Al Masani RKM, Rupani PF. Taxonomic classification of sulphate‐reducing bacteria communities attached to biocathode in hydrogen‐producing microbial electrolysis cell. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2021. 10.1007/s13762-021-03635-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Keller KL, Wall JD, Chhabra S. Methods for engineering sulfate reducing bacteria of the genus Desulfovibrio . Methods Enzymol. 2011;497:503–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wall JD, Zane GM, Juba TR, Kuehl JV, Ray J, Chhabra SR, et al. Deletion mutants, archived transposon library, and tagged protein constructs of the model sulfatereducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2021;10:e00072–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Badziong W, Thauer RK, Zeikus JG. Isolation and characterization of Desulfovibrio growing on hydrogen plus sulfate as the sole energy source. Arch Microbiol. 1978;116:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tang H‐Y, Holmes DE, Ueki T, Palacios PA, Lovley DR. Iron corrosion via direct metal‐microbe electron transfer. mBio. 2019;10:e00303–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tang H‐Y, Yang C, Ueki T, Pittman CC, Xu D, Woodard TL, et al. Stainless steel corrosion via direct iron‐to‐microbe electron transfer by Geobacter species. ISME J. 2021;15:3084–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Liang D, Liu X, Woodard TL, Holmes DE, Smith JA, Nevin KP, et al. Extracellular electron exchange capabilities of Desulfovibrio ferrophilus and Desulfopila corrodens . Environ Sci Technol. 2021;55:16195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lovley DR. Electrotrophy: other microbial species, iron, and electrodes as electron donors for microbial respirations. Bioresour Technol. 2022;345:126553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Heidelberg JF, Seshadri R, Haveman SA, Hemme CL, Paulsen IT, Kolonay JF, et al. The genome sequence of the anaerobic, sulfate‐reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pohorelic BK, Voordouw JK, Lojou E, Dolla A, Harder J, Voordouw G. Effects of deletion of genes encoding Fe‐only hydrogenase of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough on hydrogen and lactate metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Goenka A, Voordouw JK, Lubitz W, Gaertner W, Voordouw G. G. Construction of a [NiFe]‐hydrogenase deletion mutant of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Caffrey SM, Park H‐S, Voordouw JK, He Z, Zhou J, Voordouw G. Function of periplasmic hydrogenases in the sulfate‐reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Pereira PM, He Q, Valente FM, Xavier AV, Zhou J, Pereira IA, et al. Energy metabolism in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough: insights from transcriptome analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2008;93:347–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Clark ME, He Z, Redding AM, Joachimiak MP, Keasling JD, Zhou JZ, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilms: carbon and energy flow contribute to the distinct biofilm growth state. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhang W, Gritsenko MA, Moore RJ, Culley DE, Nie L, Petritis K, et al. A proteomic view of Desulfovibrio vulgaris metabolism as determined by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2006;6:4286–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tsurumaru H, Ito N, Mori K, Wakai S, Uchiyama T, Iino T, et al. An extracellular [NiFe] hydrogenase mediating iron corrosion is encoded in a genetically unstable genomic island in Methanococcus maripaludis . Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Deutzmann JS, Sahin M, Spormann AM. Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis. mBio. 2015;6:e00496–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Philips J, Monballyu E, Georg S, De Paepe K, Prévoteau A, Rabaey K, et al. An Acetobacterium strain isolated with metallic iron as electron donor enhances iron corrosion by a similar mechanism as Sporomusa sphaeroides . FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2019;95:fiy222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Philips J. Extracellular electron uptake by acetogenic bacteria: does H2 consumption favor the H2 evolution reaction on a cathode or metallic iron? Front Microbiol. 2020;10:2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Chatelus C, Carrier P, Saignes P, Libert MF, Berlier Y, Lespinat PA, et al. Hydrogenase activity in aged, nonviable Desulfovibrio vulgaris cultures and its significance in anaerobic biocorrosion. App Environ Microbio. 1987;53:1708–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Lovley DR, Holmes DE. Electromicrobiology: the ecophysiology of phylogenetically diverse electroactive microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20:5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Glasser NR, Saunders SH, Newman DK. The colorful world of extracellular electron shuttles. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2017;71:731–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Huang B, Gao S, Xu Z, He H, Pan X. The functional mechanisms and application of electron shuttles in extracellular electron transfer. Curr Microbiol. 2018;75:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Brutinel ED, Gralnick JA. Shuttling happens: soluble flavin mediators of extracellular electron transfer in Shewanella . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Van Ommen Kloeke F, Bryant RD. Localization of cytochromes in the outer membrane of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) and their role in anaerobic biocorrosion. Anaerobe. 1995;1:351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Mehta T, Coppi MV, Childers SE, Lovley DR. Outer membrane c‐type cytochromes required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8634–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Qian X, Reguera G, Mester T, Lovley DR. Evidence that OmcB and OmpB of Geobacter sulfurreducens are outer membrane surface proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Leang C, Qian X, Mester T, Lovley DR. Alignment of the c‐type cytochrome OmcS along pili of Geobacter sulfurreducens . Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4080–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Inoue K, Leang C, Franks AE, Woodard TL, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. Specific localization of the c‐type cytochrome OmcZ at the anode surface in current‐producing biofilms of Geobacter sulfurreducens . Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:211–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Deng X, Dohmae N, Nealson KH, Hashimoto K, Okamoto A. Multi‐heme cytochromes provide a pathway for survival in energy‐limited environments. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaao5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Deng X, Okamoto A. Electrode potential dependency of single‐cell activity identifies the energetics of slow microbial electron uptake process. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Chatterjee M, Fan Y, Cao F, Jones AA, Pilloni G, Zhang X. Proteomic study of Desulfovibrio ferrophilus IS5 reveals overexpressed extracellular multi‐heme cytochrome associated with severe microbiologically influenced corrosion. Sci Rep. 2021;11:15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Lovley DR, Coates JD, Blunt‐Harris EL, Phillips EJP, Woodard JC. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature. 1996;382:445–8. [Google Scholar]

- 117. Nevin KP, Lovley DR. Mechanisms for Fe(III) oxide reduction in sedimentary environments. Geomicrobiol J. 2002;19:141–59. [Google Scholar]

- 118. von Canstein H, Ogawa J, Shimizu S, Lloyd JR. Secretion of flavins by Shewanella species and their role in extracellular electron transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Marsili E, Baron DB, Shikhare ID, Coursolle D, Gralnick JA, Bond DR. Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3968–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Kotloski NJ, Gralnick JA. Flavin electron shuttles dominate extracellular electron transfer by Shewanella oneidensis . mBio. 2013;4:e00553–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]