Abstract

Children are exposed to many potentially toxic compounds in their daily lives and are vulnerable to the harmful effects. To date, very few non-invasive methods are available to quantify children’s exposure to environmental chemicals. Due to their ease of implementation, silicone wristbands have emerged as passive samplers to study personal environmental exposures and have the potential to greatly increase our knowledge of chemical exposures in vulnerable population groups. Nevertheless, there is a limited number of studies monitoring children’s exposures via silicone wristbands. In this study, we implemented this sampling technique in ongoing research activities in Montevideo, Uruguay which aim to monitor chemical exposures in a cohort of elementary school children. The silicone wristbands were worn by 24 children for 7 days; they were quantitatively analyzed using gas chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry for 45 chemical pollutants, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs), and novel halogenated flame-retardant chemicals (NHFRs). All classes of chemicals except NHFRs were identified in the passive samplers. The average number analytes detected in each wristband was 13 ± 3. OPFRs were consistently the most abundant class of analytes detected. Median concentrations of ΣOPFRs, ΣPBDEs, ΣPCBs, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and its metabolites (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane (DDD)) were 1020, 3.00, 0.52 and 3.79 ng/g wristband, respectively. Two major findings result from this research; differences in trends of two OPFRs (TCPP and TDCPP) are observed between studies in Uruguay and the United States and the detection of DDT, a chemical banned in several countries, suggests that children’s exposure profiles in these settings may differ from other parts of the world. This was the first study to examine children’s exposome in South America using silicone wristbands and clearly points to a need for further studies.

Keywords: South America, Exposome, Silicone wristband, Environmental pollutant, Personal monitoring, Children exposure

1. Introduction

The use of silicone wristbands to measure personal exposure was first published in 20141, as a novel and appealing non-invasive method for measuring human exposure to environmental chemicals. The wristbands have grown in popularity due to their advantages as passive samplers, and to date, have been used in over 30 epidemiological and toxicological studies.1-33 Specifically, silicone wristbands are popular because they are non-invasive and represent low burden to study participants.4, 16, 17, 19, 25, 33 Nevertheless, there are a limited number of studies using passive sampling with silicone wristbands to measure chemical exposure in children, especially outside of the United States (U.S.).

A handful of studies in the U.S. have used silicone wristbands to asses children’s exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)4, 33, organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs)4, 16, 29, 33, phthalates29, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)25, pesticides17, and nicotine exposure from second hand smoke19. Household characteristics were associated with differences in total exposure to PBDEs and OPFRs (i.e. age of house, vacuuming frequency)4, and PAH levels (stove/vent type, commuting via car)25. Sex differences were observed in exposure to some PAHs.25 Additionally, a dose-dependent relationship between higher OPFR exposures and teacher ratings of less responsible behavior (p = 0.07) and more external behavior problems (p = 0.03) was observed in children aged 3-5 years, while children rated by their teachers as less assertive had higher PBDE exposure (p = 0.007).33

Outside the U.S., data are lacking on exposure monitoring via wristbands for both children and adults. In low and middle-income countries, it is estimated that 250 million children do not reach their developmental potential due to poverty and other disparities, including higher burdens of environmental exposure.34 For certain classes of organic chemicals like flame retardants, children have higher exposures than adults16, 35-38, necessitating exposure monitoring specifically targeted to this age group. Furthermore, assessing personal exposure in children is critical to understand the potential effects of chemicals on their growth and development.

Given the limited research on children’s personal exposure in lower income countries using wristbands, our objective was to qualitatively and quantitatively characterize organic chemical exposures among Montevideo school children. Our study, named the Scola-Exposome, leveraged ongoing research activities within a cohort of elementary school children in Montevideo, Uruguay that aims to understand the effects of metal exposures on children’s cognitive and behavioral function.39-50 Outcomes of this study will provide valuable information on exposures to organic contaminants in children outside of the U.S.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Participants of the Scola-Exposome study included 24 children aged 6.0-7.8 years, attending first grade in 9 elementary schools in different areas of Montevideo, Uruguay. The children were participating in a larger environmental cohort study of school-aged children called Salud Ambiental Montevideo. Families recently recruited into Salud Ambiental Montevideo were screened for eligibility for Scola-Exposome. Families were first asked if they were willing to participate in the additional study and second, if they had a refrigerator in the home to store samples for a separate study purpose.

Children and their parents attended a meeting with the study coordinator at the Catholic University of Uruguay, to receive the bands and further instructions. Children took the bands out of the storage jars, placed them on their own wrists, and then were asked to wear the bands continuously during play, wash, and sleep for seven days. After the deployment period, children met again with the study coordinator during a scheduled home visit, took off the bands and placed them back in the respective jars. Detailed demographic information was collected as part of ongoing research activities in Salud Ambiental Montevideo, including maternal age, education and occupation; family structure and income. The child and family’s health-related behaviors were also queried, including the child’s personal hygiene habits (daily frequency of hand and face-washing), smokers in the house and child’s contact with smokers. Additionally, during the scheduled activities for Salud Ambiental Montevideo, a nurse took a fasting blood sample from the child’s antecubital vein for the determination of hemoglobin (an indicator of iron status & anemia) and blood lead (BLL) concentrations. The analytical procedures for both measures have been described in detail elsewhere.47

All study protocols and materials related to the study were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Uruguay. Parents/legal guardians provided written consent prior to involvement in the study; children provided verbal assent.

2.2. Chemicals

Analytical standards for 13C12-PBDEs, 13C12-polychlorniated biphenyls (PCBs), 13C6-hexabromobenzene, and 13C12-1,2-bis(2,4,6-tribromophenoxy)ethane were obtained from Wellington Labs Inc. (Guelph, ON, Canada) and 13C12-p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene, d10-diazinon, and deuterated-OPFRs were acquired from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. (Tewksbury, MA) (Table S1). Acetonitrile (ACN), ethyl acetate, hexanes, isooctane, and methanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA). Sep-Pak™ C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (500 mg, 3 cc) were obtained from Waters Inc. (Milford, MA).

2.3. Wristband Collection

Silicone wristbands (100% silicone, https://24hourwristbands.com/, Houston, TX) were cleaned prior to deployment in the second half of 2018 using the protocol described by O’Connell et al.1 Briefly, ≤65 g of silicone were soaked in 800 mL of mixed organic solvent (see below) for five extractions for a minimum of 2.5 hours each at 60 rotations per minute using an Innova 2000 (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Edison, NJ) platform shaker. The first three pre-cleaning extractions consisted of ethyl acetate/hexanes (1:1, v:v) and the last two extractions used ethyl acetate/methanol (1:1, v:v) as additional pre-cleanings. Cleaned wristbands were air-dried in a fume hood and then stored in 60-mL certified contaminant free glass amber jars (VWR International, Radnor, PA) until deployment. After participants wore the wristbands for a 7-day period, the bands were placed back in their respective jars and stored at −20°C at the Catholic University of Uruguay, and shipped back to the University at Buffalo, where samples were stored at −40°C until analysis.

2.4. Wristband Extraction.

Using solvent-rinsed surgical scissors, wristbands were cut into 8 equal pieces and two pieces (1 g) were transferred to 50-mL acid-washed glass centrifuge tubes for extraction. Samples were then spiked with 5 ng of surrogate standards dropwise directly onto the samples. Extraction and cleanup was performed using a method previously described by Kile et al.4, which was modified to decrease the amount of organic solvent used. Briefly, extraction was performed twice, each using 25 mL of ethyl acetate for two hours on an orbital shaker at 60 rotations per minute. Ethyl acetate extracts were combined and concentrated to 300 μL, then ACN (3 mL) was added to samples prior to SPE cleanup. The SPE cartridges (C18, 500 mg, 3 cc) were rinsed with ACN (6 mL). Each of the extracts was passed through an SPE cartridge, collecting the eluent in a 10-mL acid-washed glass centrifuge tube and further eluted with ACN (6 mL) into the same collection vessel. Samples were then evaporated to dryness and reconstituted in 200 μL of 13C12-PCB-138 in isooctane and transferred to 2-mL amber vials. An aliquot (50 μL) of each sample was transferred to a 200-μL conical insert for analysis.

2.5. Instrumental Analysis

Wristband samples were analyzed for a total of 45 chemicals including 14 PCBs, 13 PBDEs, 6 OPFRs, 8 novel halogenated flame retardants (NHFRs), and 4 pesticides. Analysis of samples was performed using a Trace GC Ultra™ coupled to a TSQ Quantum XLS™ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL) with electron ionization mode. A programmable temperature vaporization inlet was utilized for injection and was set at an initial temperature of 89°C, then increased at a rate of 7.5°C/min for 0.2 minutes. The analytes were then transferred to the column at 330°C for 1 minute. The split flow was set at 60 mL/min with a splitless time of 1.13 minutes. The flow rate remained constant at 1.0 mL/min with helium (99.999% purity) as the carrier gas. Separation was achieved on a 15-m DB-5HT™ capillary column with a 0.25 mm internal diameter, and a 0.10 μm film thickness (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature of 100°C was held for 2 minutes, ramped at 10°C/min to 210°C, followed by a second ramp at 20°C/min to a final temperature of 330°C, and was held for 10 minutes. Retention times, mass fragmentation characteristics, and optimized collision energies are presented in Table S2.

2.6. Quality Assurance/Quality Control.

Pre-baked (250°C) aluminum foil was used to weigh wristbands to prevent any contamination; and all tools were rinsed thoroughly with ethyl acetate prior to and between handling of each wristband. Isotope dilution was utilized for the quantitation of PBDEs, PCBs, OPFRs, NHFRs, and pesticides using isotopically labelled standards (Table S1). Analytical figures of merit are provided in the Table S2; method limits of detection (LODs) were determined based on 3 times the standard deviation of the lowest observed concentration spiked in wristband matrix (n=7) and ranged from 0.001 to 0.014 ng/g. Limits of quantitation (LOQs) were determined based on 10 times the standard deviation of the lowest observed concentration spiked in wristband matrix (n=7) ranging from 0.003 to 0.047 ng/g. Recovery experiments were performed by spiking (n=3) cleaned wristbands (1g) with a standard solution containing 5 ng/g of each analyte. The overall recoveries ranged from 50 to 122; more than 86% of the target analytes have recoveries greater than 70%. Laboratory blanks (n=5) were used to subtract any potential interferences. To confirm positive detection of a targeted compound, a retention time match of ± 0.25 min with the reference standard was used.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (geometric mean, median, interquartile range) for the analytes were performed using R 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Further analysis was performed for chemicals with a detection frequency >50%. For compounds below the LOQ, values were assigned equal to the LOD divided by the square root of 2. Spearman correlations for the analytes and descriptive statistics for the sociodemographic variables were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, TX).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Study Outline

Twenty-four silicone wristbands were deployed and all participants completed the study according to previously described guidelines. One wristband could not be analyzed due to high chromatographic interferences, reducing the sample to 23 wristbands that were quantitatively analyzed for 45 chemicals. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. The study population was 60.9% female and participant age ranged 6.0 - 7.8 years. Furthermore, 39% of families reported having a car, 100% cleaned their floors more than once per week, and 18 out of 23 families reported cleaning dust more than one time per week. Of note, the children had overall good nutritional status, with little evidence of anemia and all had BLL < 10 μg/dL. On the other hand, 13% had BLL ≥ 5 μg/dL.

Table 1:

Characteristics of children participating in Scola-Exposome with passive sampler data

| Characteristic | N | % or Mean ± Standard Deviation |

Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |||

| % Boys | 23 | 39.1% | |

| Age (months) | 23 | 82.2 ± 4.7 | 72 – 94 |

| Child always washes hands prior to eating | 23 | 73.9% | |

| Child does not share space with smokers | 23 | 73.9% | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 23 | 13.2 ± 0.9 | 11.3 – 14.6 |

| Blood lead concentration (μg/dL) | 23 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 3.3 – 7.6 |

| BLL ≥ 5 μg/dL | 13.0% | ||

| Parent/Household Characteristics | |||

| Mother’s age (y) | 23 | 32.2 ± 5.2 | 24 – 43 |

| Mother continued her education after 14 y of age | 23 | 30.4% | |

| Parents are married or cohabitating | 23 | 73.9% | |

| Child lives with: | 22 | ||

| Both parents | 40.9% | ||

| Mother only | 13.6% | ||

| Other arrangement | 45.4% | ||

| Mother currently smokes | 23 | 43.5% | |

| Monthly family income < 15,0001 Uruguayan pesos | 23 | 52.2% | |

In the second half of 2018, when the study was conducted, this monthly income was equivalent to roughly 465 U.S. dollars; according to CEIC (https://www.ceicdata.com/en), the average monthly household income in Montevideo was just shy of 74,000 Uruguayan pesos.

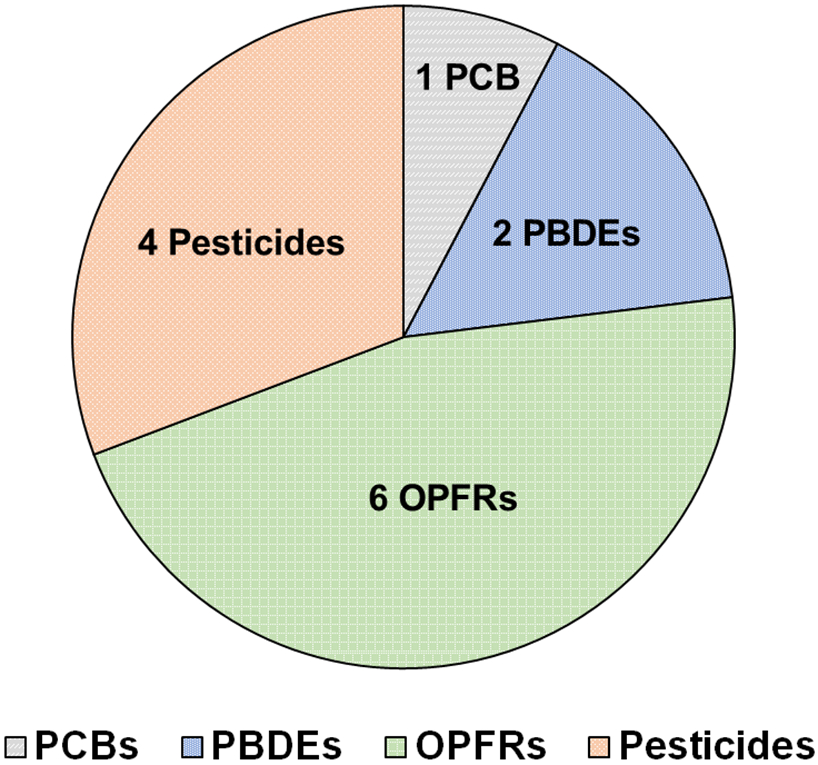

With the exception of NHFRs, at least one analyte from the five groups of chemicals (PCBs, PBDEs, OPFRs, NHFRs, and pesticides) in the method was detected, with each extract from the wristbands containing 8 to 19 detected chemicals (13 ± 3, mean ± standard deviation (SD)). Overall, 13 out of 45 compounds were detected in over 50% of the samples (Figure 1, Table 2). For the analytes detected at less than 50% detection frequency, quantities of individual target analytes in each wristband sample are further provided in the supplemental material (Tables S3-6). OPFRs were found at the highest concentration and were the most frequently detected group of compounds, contributing 94 ± 2% of total chemical concentrations.

Figure 1:

Thirteen analytes belonging to five different classes of chemicals were detected in >50% of wristband samples from the Scola-Exposome study in Montevideo, Uruguay. Classes of chemicals include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs) and pesticides.

Table 2:

Concentrations of 13 analytes (ng/g wristband) with >50% detection frequency in wristbands from the Scola-Exposome study in Montevideo, Uruguay (n=23). LOQ represents the limit of quantitation. For the analytes detected at less than 50% detection frequency, quantities of individual target analytes in each wristband sample are further provided in the supplemental material (Tables S3-6).

| Compound |

Percent

detect (n) |

LOQ | Median |

Geometric

mean |

Percentiles | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 75th | ||||||

| PCB-180 1 | 69.6 (16) | 0.028 | 0.33 | 0.13 | <LOQ | 0.52 | 2.32 |

| ΣPCBs | - | - | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 1.18 | 8.35 |

| BDE-47 | 95.7 (22) | 0.019 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.57 | 1.63 | 138 |

| BDE-99 | 69.6 (16) | 0.019 | 0.81 | 0.22 | <LOQ | 1.47 | 190 |

| ΣPBDEs | - | - | 3.00 | 2.73 | 1.24 | 5.06 | 433 |

| TBP | 82.6 (19) | 0.006 | 66.4 | 12.8 | 39.4 | 136 | 510 |

| TCEP | 87.0 (20) | 0.023 | 20.8 | 8.99 | 3.77 | 77.3 | 1420 |

| TCPP | 82.6 (19) | 0.017 | 208 | 65.3 | 158 | 1010 | 4480 |

| TDCPP | 56.5 (13) | 0.009 | 5.10 | 0.64 | <LOQ | 78.5 | 1500 |

| TPhP | 95.7 (22) | 0.007 | 85.4 | 97.0 | 57.2 | 429 | 8920 |

| EHDPHP | 100 (23) | 0.009 | 290 | 337 | 131 | 661 | 4820 |

| ΣOPEs | - | - | 1020 | 1370 | 806 | 2970 | 12300 |

| Diazinon | 95.7 (22) | 0.020 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 7.68 | 32.4 | 340 |

| p,p’-DDE | 100 (23) | 0.027 | 1.30 | 1.32 | 0.85 | 2.12 | 5.19 |

| p,p’-DDD | 78.3 (18) | 0.020 | 0.67 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 1.46 | 4.60 |

| p,p’-DDT | 87.0 (20) | 0.007 | 1.63 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 3.67 | 13.7 |

Abbreviations are as follows: 2,2’,3,4,4’,5,5’-heptachlorobiphenyl (PCB-180), 2,2’,4,4’-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47), 2,2’,4,4’,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-99), tributyl phosphate (TBP), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) (TCEP), tris (chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP), tris(1,3-dichloroisopropyl) phosphate (TDCPP), triphenyl phosphate (TPhP), 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate (EHDPHP), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane (p,p’-DDD), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p’-DDE), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (p,p’-DDT).

3.2. Polychlorinated Biphenyls

PCBs were detected in 19 out of 23 wristbands and exhibited the lowest concentrations of all compound classes with a median sum of PCBs (ΣPCBs) concentration of 0.52 (range, 0.19 – 8.35) ng/g wristband (Table 2). On average, two PCB congeners were detected in each wristband and the maximum number of congeners in a single wristband analyzed was four. PCB-180 was the most frequently detected, in 16 wristbands, and contributed over 50% of ΣPCB concentrations. PCB-170 had the second highest detection frequency in 5 out of 23 wristbands, however it only contributed 5% of ΣPCB concentrations. All other congeners were detected in only one or two wristbands, furthermore, there were three wristbands that did not contain any PCBs. Interestingly, the three samples with the highest ΣPCB concentrations also had the greatest number of PCBs observed, with three or four congeners.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no quantitative reports of PCB concentrations in wristband samplers worn by children in any country. However, one study detected five PCBs (PCB-102, PCB-88, PCB-93, PCB-95, PCB-98) in wristbands of urban participants, mostly adults, living in the U.S. in a qualitative screening.14 The general lack of detection of PCBs in other studies is most likely due the location and different exposure profiles of various settings; however, analytical differences and limits of detection of targeted methods versus large chemical screening can also play a role.

In Uruguay, the entry and trade of PCBs had not been regulated prior to the Stockholm Convention calling for a Global Monitoring Program (GMP) of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in 2007. Prior to that, it was estimated that 40,000 transformers, which are a major source of PCBs, were operating in Uruguay in 2006.51 The country has had limited experience regarding management of PCBs due to lack of infrastructure and equipment to contain and dispose of them in an environmentally appropriate manner. To address this concern, a project aimed at implementing systems for the safe disposal of PCBs was crafted in 2008.51

Previous studies have aimed to research PCBs in Uruguay and as a part of the GMP performed in 2007, PCBs were detected in breast milk of Uruguayan women at levels above 25 ng/g lipid, and in air samples in Montevideo above 200 pg/m3.52 Air concentrations were the second highest level of the seven Latin American countries tested since the GMP began. Results of efforts to remove and properly dispose of PCBs in Uruguay have shown to be effective as concentrations in air samples slightly decreased between 2010 to 2011 but have not been reported since52; nonetheless concentrations were detected in the wristbands from the Scola-Exposome sample.

3.3. Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers

The presence of PBDEs was confirmed in 22 out of 23 wristbands, with a median concentration of the sum of PBDEs (ΣPBDEs) of 3.00 (range, 0.26 – 433) ng/g wristband (Table 2). Each wristband contained 0 – 9 congeners (3 ± 2, mean ± SD). BDE-47 was most frequently detected, in 22 wristbands, followed by BDE-99 in 16 and BDE-100 in 9 out of 23 wristbands. These three congeners made up an average of 95% of ΣPBDE concentrations. BDE-47 had the greatest contribution, an average of 56%, to ΣPBDE concentrations, followed by BDE-99 and −100 at 26% and 13%, respectively. These three congeners are the most abundant BDEs detected globally, since they comprised the largest percent of one of the most commonly manufactured PBDE mixtures.53, 54

Results from this study are similar to trends reported in preschoolers’ wristbands from Oregon, where BDE-47 and −99 also had the highest concentrations.4 However, ΣPBDE concentrations were higher compared to our findings, with an average of 4.49 ± 5.59 ng/g/day and reaching up to 171 ng/g/day.4 BDE-47 was also the most abundant congener in wristband samplers of adults from North Carolina, followed by BDE-99 and −100.11 Furthermore, both adults in North Carolina and children in Oregon had greater mean concentrations of BDE-47, 55.911 and 30.4 ng/g4 respectively, than observed in our study.

One finding from household surveys may provide some explanation for lower concentrations of PBDEs in our study compared to the U.S. Caregivers in the Salud Ambiental Montevideo cohort reported that 93.5% of families never used carpet cleaner, suggesting that carpets might not be present in the home. PBDEs are used significantly in polyurethane foams that are recycled and used in the production of carpet padding.55 Higher levels of PBDEs have also been observed in serum samples from carpet installation workers compared to the general U.S. population.56

3.4. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants

A mean of 5 ± 1 (range, 2 – 6) OPFR compounds were detected in each wristband; 11 wristbands contained all six OPFRs analyzed. Total OPFR (ΣOPFR) concentrations ranged from 208 to 12,300 ng/g, with a median of 1020 ng/g band (Table 2). All OPFRs were detected at greater than 50% frequency in samples and 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate (EHDPHP) had the highest median concentration of 290 ng/g and was the only OPFR detected in all 23 wristbands. A previous study by Hammel et al.29 has also reported 100% detection frequency of EHDPHP in wristbands of children from North Carolina. In our study, tris(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TCPP) had the second highest median concentration of 208 ng/g and was detected in 19 of 23 wristbands, followed by triphenyl phosphate (TPhP) which was found in 22 of 23 children’s wristbands. Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCPP) had the lowest median concentration of 5.10 ng/g and was least frequently detected, in 13 wristbands. Comparatively, in wristbands from children in Oregon, TDCPP had the highest mean concentrations of 154 ± 171 ng/g/day followed by TPhP at 134 ± 290 ng/g/day.4 Additionally, in wristbands worn by children from North Carolina, TPhP had the greatest median concentration of 872.9 ng/g band, followed by TDCPP with 179.7 ng/g.29 Our study reveals differences in exposure patterns of OPFRs among children in Uruguay compared to the U.S. In sum, OPFR concentrations were lower in wristbands of Montevideo children, and specifically, had lowest levels of TDCPP compared to children in other studies, but Uruguayan children also had highest exposure to TCPP.

A recent study reported that in Southern California, longer commute times were associated with higher TDCPP exposures.27 Separate studies also reported that TDCPP is the dominant OPFR found in cars in the United Kingdom57, and is frequently detected in dashboard dust worldwide58, 59. In the Scola-Exposome population, only 9 of 23 families reported having cars, indicating that a majority of the children either walk or utilize public transportation, possibly explaining the lower levels of TDCPP observed in our study. On the other hand, it has been observed that TCPP concentrations exceeded all other OPFRs in living room dust59 and is also used widely in furniture in the U.S.60 The lower concentrations of TDCPP and higher concentrations of TCPP found in wristbands from Uruguay children compared to the U.S. suggest that children in Uruguay travel by car less frequently and possibly spend more time in or around the house. The differences in OPFR concentrations among settings could arise from variations in manufacturing and additives used in products from different countries, as well as in differences in socioeconomic status and lifestyles of the participants. The country-specific patterns of children’s exposure highlight the need for studies in lower income countries to understand exposures and outcomes worldwide.

3.5. Pesticides

Four pesticides were analyzed in wristband extracts, including p,p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), its metabolites (p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane (DDD)), and the insecticide diazinon. All four compounds were detected in more than 75% of samples (Table 2). The primary metabolite of DDT, DDE, was identified in 100% of wristbands with a median concentration of 1.30 ng/g. The parent compound DDT was detected in 20 wristbands, with median concentration of 1.63 ng/g. In 16 out of 23 wristbands, the concentration of p,p’-DDT was higher than DDE. To estimate exposures to recent applications of DDT, the ratio of p,p’-DDT/( p,p’-DDE + p,p’-DDD) was calculated as previously performed in other wristband studies.2, 6 A ratio greater than one suggests exposure to a recent application of DDT61-63, and was observed in ten of 23 wristbands in our study.

DDT is also included in the Stockholm Convention’s GMP in Uruguay.52 In 2009, the sum of DDT and its 5 total metabolites and isomers were identified in breast milk of Uruguayan women at levels greater than 120 ng/g lipid.52 In addition, Montevideo air samples in 2011 were above 1.0 pg/m3, both with DDE as the major isomer identified.52 High levels of pesticides observed in the study in Uruguay may have been due to lack of regulation and proper disposal facilities for outdated and banned chemicals,64 thus leaving waste on farms or near water resources, and in some cases burned or utilized for other purposes.65 Additionally, dicofol, an organochlorine pesticide known to contain DDT (due to its use as intermediate in dicofol production), may be a secondary source of DDT in Uruguay. Dicofol has been documented as a source of exposure to DDT in a number of countries.66, 67 Currently, there are no studies specifically linking dicofol to DDT exposure in Uruguay, but it appears that in 2011 there was one commercial formulation approved for use in the country.68 The specific reasons for exposure to recent applications of DDT in urban Uruguayan children are unknown and should be investigated further.

DDE was detected in 55.7% of wristbands worn by Latina adolescent females from California.17 However outside the U.S., a study in Peru had a higher frequency of detection of DDT and its metabolites in 63 of 65 wristbands, with concentrations ranging from 8.8 to 5400 ng/g.6 Four of the wristbands from Scola-Exposome, were within the reported range from the wristbands in Peru, however most of the observed concentrations in wristbands of Uruguayan children were lower. We observed lower concentrations of DDT and metabolites in urban school-age children, whereas the demographic in Peru consisted of mainly adults that most commonly reported their occupation as “farm worker”; only 12 of 68 the Peruvian participants were students. Additionally, Bergmann et al., observed that 48% of Peruvian wristbands had p,p’-DDT/(p,p’-DDE + p,p’-DDD) ratios greater that one.6 Our study found similar results, with ten of 23 wristbands (44%) having DDT ratios greater than one, suggesting that despite ceased production, both urban and farming populations in both countries may have relatively recent exposures to DDT. The complementary results from both settings indicate the need to further investigate exposure to DDT and its metabolites across South America.

Diazinon was detected in 22 of 23 wristbands (Table 2) with a median concentration of 12.7 ng/g. Diazinon was used as a household insecticide since 1956 in the European Union, until 2007 when this use was prohibited.69 Further review of literature focused on environmental analysis of diazinon in Uruguay, revealed that it has been detected in 12% of surface water samples from two lagoons (Laguna de Rocha and Laguna de Castillos) in Uruguay approximately 200-250 km east of Montevideo, potentially explaining the high detection frequency in humans.70 To the best of our knowledge, there is no quantitative data available to compare diazinon concentrations in silicone wristbands in other studies.

3.6. Spearman correlation coefficients

Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) in Table 3 were calculated for analytes that had at least 50% detection frequency. Strong correlations between chemicals can tell us how these compounds, as a class or individually, are used in the industry in the specific region and point to potentially common sources of exposure to different chemicals. Moreover, comparing correlations between different study populations is valuable in uncovering differences in sources or patterns of exposure. BDE-47 and 99 were positively correlated (ρ = 0.51, p < 0.05), as expected given that PBDEs are manufactured in mixtures and previous studies have found that BDE-47 and −99 are the two major congeners in the penta-BDE formulation.53, 54 Hammel et al. also observed similar correlations between these two congeners in wristband samples from adults in North Carolina.11 Furthermore, DDT and its metabolites were highly positively correlated (ρ 0.88 – 0.93, p < 0.01). TPhP and EHDPHP were also positively correlated (ρ = 0.79, p < 0.01), likely due to their structural similarity. EHDPHP is used primarily in food-packaging plastics, rubber, paints, textile coatings, and adhesives71, while TPhP is used primarily in polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane foams, hydraulic fluids, and themroplastics.72 Even though these two chemicals have different primary uses, they are both applied in a wide variety of products such as electronics, many of which may overlap, thus leading to the observed correlation. No other compounds in the OPFR class significantly correlated with each other. In contrast, wristbands from adults in Southern California showed significant positive correlations between TDCPP and tributyl phosphate, tris (2-butoxyethyl) phosphate, TCPP and EHDPHP.27 Correlations between TDCPP and TCPP observed in Southern California are attributed to co-application in products containing polyurethane foams as well as dust from vehicles.27 Different correlations among compounds in studies conducted in the U.S. and Uruguay point towards the need for further exposome research worldwide.

Table 3:

Spearman correlations among chemical compounds detected in at least 50% of silicone wristbands in Scola-Exposome study.

| PCB-180 | BDE-47 | BDE-99 | TBP | TCEP | TCPP | TDCPP | TPhP | EHDPHP | Diazinon | p,p’-DDE | p,p’-DDD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDE-471 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| BDE-99 | 0.23* | 0.51** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TBP | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.43* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TCEP | −0.19 | −0.08 | 0.20 | 0.42* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TCPP | −0.40* | −0.15 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TDCPP | 0.28 | −0.11 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.24 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TPhP | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.35* | 0.05 | 0.19 | −0.25 | - | - | - | - | - |

| EHDPHP | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.30 | −0.38 | 0.79*** | - | - | - | - |

| Diazinon | −0.27 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.31 | - | - | - |

| p,p’-DDE | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.22 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.17 | - | - |

| p,p’-DDD | 0.11 | −0.18 | 0.18 | 0.10 | −0.15 | −0.25 | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.89*** | - |

| p,p’-DDT | 0.09 | −0.12 | 0.17 | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.16 | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.15 | −0.14 | 0.88*** | 0.93*** |

p<0.1

p<0.05

p<0.01

Abbreviations are as follows: 2,2’,4,4’-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47), 2,2’,4,4’,5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-99), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane (p,p’DDD), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p’DDE), p,p’-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (p,p’DDT), 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate (EHDPHP), 2,2’,3,4,4’,5,5’-heptachlorobiphenyl (PCB-180), tributyl phosphate (TBP), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) (TCEP), tris (chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP), tris(1,3-dichloroisopropyl)phosphate (TDCPP), and triphenyl phosphate (TPhP).

3.7. Future Directions

Given the scarcity of studies on exposure assessment in children via silicone wristbands, more research is needed to better understand to what extent chemical concentrations in the wristbands reflect body burdens of exposure. Moreover, several issues with respect to study design need to be clarified, including the duration and frequency of sampling to reflect typical levels and variability of exposures. Finally, epidemiological studies are needed to understand how the levels of exposure observed in our study and other related research, relate to both disease processes and functional health outcomes.

4. Conclusions

Most studies using silicone wristbands currently focus on chemical exposures in adults living in the U.S. Additional studies are needed to understand the extent and patterns of chemical exposures in children, specifically in settings other than the U.S. Information on low and middle-income countries, where exposures are potentially greater due to unregulated use of chemicals, is particularly lacking and should be prioritized. This study is the first to focus on children’s exposure using silicone wristbands in South America, which reveals that legacy pollutants remain a concern for Uruguayan children. High levels of TCPP and lower concentrations of TDCPP in Scola-Exposome wristbands highlight lifestyle and sociodemographic differences in study samples from Uruguay and the U.S. This study represents an important stride towards determining children’s exposome outside of the Global North. Furthermore, results provide data on chemical exposure of a continually studied population, vital to unveiling the exposome and the health effects of children’s exposures to chemical mixtures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants in the study and their families as well as study staff of Salud Ambiental Montevideo. This work was supported by the Research and Education in Energy, Environment and Water (RENEW) Institute at the University at Buffalo.

References

- 1.O’Connell SG; Kincl LD; Anderson KA, Silicone Wristbands as Personal Passive Samplers. Environmental Science & Technology 2014, 48, (6), 3327–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donald CE; Scott RP; Blaustein KL; Halbleib ML; Sarr M; Jepson PC; Anderson KA, Silicone wristbands detect individuals' pesticide exposures in West Africa. R. Soc. Open Sci 2016, 3, (8), 160433/1–160433/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammel SC; Hoffman K; Webster TF; Anderson KA; Stapleton HM, Measuring Personal Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and Hand Wipes. Environmental Science & Technology 2016, 50, (8), 4483–4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kile ML; Scott RP; O'Connell SG; Lipscomb S; MacDonald M; McClelland M; Anderson KA, Using silicone wristbands to evaluate preschool children's exposure to flame retardants. Environmental Research 2016, 147, 365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson KA; Points GL; Donald CE; Dixon HM; Scott RP; Wilson G; Tidwell LG; Hoffman PD; Herbstman JB; O'Connell SG, Preparation and performance features of wristband samplers and considerations for chemical exposure assessment. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2017, 27, (6), 551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergmann AJ; North PE; Vasquez L; Bello H; Ruiz M. d. C. G.; Anderson KA, Multi-class chemical exposure in rural Peru using silicone wristbands. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 2017, 27, (6), 560–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vidi P-A; Anderson KA; Poutasse C; Chen H; Anderson R; Salvador-Moreno N; Mora DC; Daniel SS; Laurienti PJ; Arcury TA, Personal samplers of bioavailable pesticides integrated with a hair follicle assay of DNA damage to assess environmental exposures and their associated risks in children. Mutat Res 2017, 822, 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aerts R; Joly L; Szternfeld P; Tsilikas K; De Cremer K; Castelain P; Aerts J-M; Van Orshoven J; Somers B; Hendrickx M; Andjelkovic M; Van Nieuwenhuyse A, Silicone Wristband Passive Samplers Yield Highly Individualized Pesticide Residue Exposure Profiles. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52, (1), 298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann AJ; Points GL; Scott RP; Wilson G; Anderson KA, Development of quantitative screen for 1550 chemicals with GC-MS. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, (13), 3101–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon HM; Scott RP; Holmes D; Calero L; Kincl LD; Waters KM; Camann DE; Calafat AM; Herbstman JB; Anderson KA, Silicone wristbands compared with traditional polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure assessment methods. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2018, 410, (13), 3059–3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammel SC; Phillips AL; Hoffman K; Stapleton HM, Evaluating the Use of Silicone Wristbands To Measure Personal Exposure to Brominated Flame Retardants. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52, (20), 11875–11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicole W., Wristbands for Research: Using Wearable Sensors to Collect Exposure Data after Hurricane Harvey. Environmental Health Perspectives 2018, 126, (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulik LB; Hobbie KA; Rohlman D; Smith BW; Scott RP; Kincl L; Haynes EN; Anderson KA, Environmental and individual PAH exposures near rural natural gas extraction. Environmental Pollution 2018, 241, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon HM; Barton M; Bergmann AJ; Hoffman P; Paulik LB; Points GL 3rd; Poutasse CM; Scott RP; Smith B; Tidwell LG; Anderson KA; Armstrong G; Bondy M; Halbleib ML; Hamilton W; Haynes E; Herbstman J; Jepson P; Kile ML; Kincl L; Rohlman D; Laurienti PJ; North P; Petrosino J; Walker C; Waters KM, Discovery of common chemical exposures across three continents using silicone wristbands. R Soc Open Sci 2019, 6, (2), 181836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donald CE; Scott RP; Wilson G; Hoffman PD; Anderson KA, Artificial turf: chemical flux and development of silicone wristband partitioning coefficients. Air Quality Atmosphere and Health 2019, 12, (5), 597–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson EA; Stapleton HM; Calero L; Holmes D; Burke K; Martinez R; Cortes B; Nematollahi A; Evans D; Anderson KA; Herbstman JB, Differential exposure to organophosphate flame retardants in mother-child pairs. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harley KG; Parra KL; Camacho J; Bradman A; Nolan JES; Lessard C; Lazaro G; Cardoso E; Gallardo D; Gunier RB; Anderson KA; Poutasse CM; Scott RP, Determinants of pesticide concentrations in silicone wristbands worn by Latina adolescent girls in a California farmworker community: The COSECHA youth participatory action study. Sci Total Environ 2019, 652, 1022–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manzano CA; Dodder NG; Hoh E; Morales R, Patterns of Personal Exposure to Urban Pollutants Using Personal Passive Samplers and GC x GC/ToF-MS. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53, (2), 614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quintana PJE; Hoh E; Dodder NG; Matt GE; Zakarian JM; Anderson KA; Akins B; Chu L; Hovell MF, Nicotine levels in silicone wristband samplers worn by children exposed to secondhand smoke and electronic cigarette vapor are highly correlated with child's urinary cotinine. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology 2019, 29, (6), 733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohlman D; Dixon HM; Kincl L; Larkin A; Evoy R; Barton M; Phillips A; Peterson E; Scaffidi C; Herbstman JB; Waters KM; Anderson KA, Development of an environmental health tool linking chemical exposures, physical location and lung function. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, (1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohlman D; Donatuto J; Heidt M; Barton M; Campbell L; Anderson KA; Kile ML, A Case Study Describing a Community-Engaged Approach for Evaluating Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Exposure in a Native American Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romanak KA; Wang S; Stubbings WA; Hendryx M; Venier M; Salamova A, Analysis of brominated and chlorinated flame retardants, organophosphate esters, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in silicone wristbands used as personal passive samplers. Journal of Chromatography A 2019, 1588, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S; Romanak KA; Stubbings WA; Arrandale VH; Hendryx M; Diamond ML; Salamova A; Venier M, Silicone wristbands integrate dermal and inhalation exposures to semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs). Environ. Int 2019, 132, 105104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig JA; Ceballos DM; Fruh V; Petropoulos ZE; Allen JG; Calafa AM; Ospina M; Stapleton HM; Hammel S; Gray R; Webster TF, Exposure of Nail Salon Workers to Phthalates, Di(2-ethylhexyl) Terephthalate, and Organophosphate Esters: A Pilot Study. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53, (24), 14630–14637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin EZ; Esenther S; Mascelloni M; Irfan F; Godri Pollitt KJ, The Fresh Air Wristband: A Wearable Air Pollutant Sampler. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuy Y; Sweck SO; Dockery CR; Potts GE, HPLC detection of organic gunshot residues collected with silicone wristbands. Analytical Methods 2020, 12, (1), 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddam A; Tait G; Herkert N; Hammel SC; Stapleton HM; Volz DC, Longer commutes are associated with increased human exposure to tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate. Environment International 2020, 136, 105499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang SR; Romanak KA; Hendryx M; Salamova A; Venier M, Association between Thyroid Function and Exposures to Brominated and Organophosphate Flame Retardants in Rural Central Appalachia. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54, (1), 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammel SC; Hoffman K; Phillips AL; Levasseur JL; Lorenzo AM; Webster TF; Stapleton HM, Comparing the Use of Silicone Wristbands, Hand Wipes, And Dust to Evaluate Children's Exposure to Flame Retardants and Plasticizers. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y; Peris A; Rifat MR; Ahmed SI; Aich N; Nguyen LV; Urik J; Eljarrat E; Vrana B; Jantunen LM; Diamond ML, Measuring exposure of e-waste dismantlers in Dhaka Bangladesh to organophosphate esters and halogenated flame retardants using silicone wristbands and T-shirts. Sci. Total Environ 2020, 720, 137480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reche C; Viana M; van Drooge BL; Fernandez FJ; Escribano M; Castano-Vinyals G; Nieuwenhuijsen M; Adami PE; Bermon S, Athletes' exposure to air pollution during World Athletics Relays: A pilot study. Sci. Total Environ 2020, 717, 137161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hendryx M; Wang SR; Romanak KA; Salamova A; Venier M, Personal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Appalachian mining communities. Environmental Pollution 2020, 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipscomb ST; McClelland MM; MacDonald M; Cardenas A; Anderson KA; Kile ML, Cross-sectional study of social behaviors in preschool children and exposure to flame retardants. Environmental Health 2017, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black M; Walker S; Fernald L; Andersen C; DiGirolamo A; Lu C; McCoy D; Fink G; Shawar Y; Shiffman J; Devercelli A; Wodon Q; Vargas-Baron E; Grantham-Mcgregor S, Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. The Lancet 2016, 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butt CM; Congleton J; Hoffman K; Fang M; Stapleton HM, Metabolites of Organophosphate Flame Retardants and 2-Ethylhexyl Tetrabromobenzoate in Urine from Paired Mothers and Toddlers. Environmental Science & Technology 2014, 48, (17), 10432–10438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butt CM; Hoffman K; Chen A; Lorenzo A; Congleton J; Stapleton HM, Regional comparison of organophosphate flame retardant (PFR) urinary metabolites and tetrabromobenzoic acid (TBBA) in mother-toddler pairs from California and New Jersey. Environment International 2016, 94, 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cequier E; Sakhi AK; Marcé RM; Becher G; Thomsen C, Human exposure pathways to organophosphate triesters — A biomonitoring study of mother–child pairs. Environment International 2015, 75, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cowell WJ; Stapleton HM; Holmes D; Calero L; Tobon C; Perzanowski M; Herbstman JB, Prevalence of historical and replacement brominated flame retardant chemicals in New York City homes. Emerging Contaminants 2017, 3, (1), 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barg G; Daleiro M; Queirolo EI; Ravenscroft J; Manay N; Peregalli F; Kordas K, Association of low lead levels with behavioral problems and executive function deficits in schoolers from Montevideo, Uruguay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, (12), 2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kordas K; Queirolo EI; Ettinger AS; Wright RO; Stoltzfus RJ, Prevalence and predictors of exposure to multiple metals in preschool children from Montevideo, Uruguay. Sci. Total Environ 2010, 408, (20), 4488–4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Queirolo EI; Ettinger AS; Stoltzfus RJ; Kordas K, Association of anemia, child and family characteristics with elevated blood lead concentrations in preschool children from Montevideo, Uruguay. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2010, 65, (2), 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kordas K; Ardoino G; Ciccariello D; Manay N; Ettinger AS; Cook CA; Queirolo EI, Association of maternal and child blood lead and hemoglobin levels with maternal perceptions of parenting their young children. NeuroToxicology 2011, 32, (6), 693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rink SM; Ardoino G; Queirolo EI; Cicariello D; Manay N; Kordas K, Associations Between Hair Manganese Levels and Cognitive, Language, and Motor Development in Preschool Children from Montevideo, Uruguay. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2014, 69, (1), 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kordas K; Ardoino G; Ciccariello D; Coffman DL; Queirolo EI; Manay N; Ettinger AS, Patterns of exposure to multiple metals and associations with neurodevelopment of preschool children from Montevideo, Uruguay. J Environ Public Health 2015, 2015, 493471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy A; Queirolo E; Peregalli F; Manay N; Martinez G; Kordas K, Association of blood lead levels with urinary F2-8α isoprostane and 8-hydroxy-2-deoxy-guanosine concentrations in first-grade Uruguayan children. Environ. Res 2015, 140, 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kordas K; Queirolo EI; Manay N; Peregalli F; Hsiao PY; Lu Y; Vahter M, Low-level arsenic exposure: Nutritional and dietary predictors in first-grade Uruguayan children. Environ. Res 2016, 147, 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kordas K; Burganowski R; Roy A; Peregalli F; Baccino V; Barcia E; Mangieri S; Ocampo V; Manay N; Martinez G; Vahter M; Queirolo EI, Nutritional status and diet as predictors of children's lead concentrations in blood and urine. Environ. Int 2018, 111, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravenscroft J; Roy A; Queirolo EI; Manay N; Martinez G; Peregalli F; Kordas K, Drinking water lead, iron and zinc concentrations as predictors of blood lead levels and urinary lead excretion in school children from Montevideo, Uruguay. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burganowski R; Vahter M; Queirolo EI; Peregalli F; Baccino V; Barcia E; Mangieri S; Ocampo V; Manay N; Martinez G; Kordas K, A cross-sectional study of urinary cadmium concentrations in relation to dietary intakes in Uruguayan school children. Sci. Total Environ 2019, 658, 1239–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frndak S; Barg G; Canfield RL; Quierolo EI; Manay N; Kordas K, Latent subgroups of cognitive performance in lead- and manganese-exposed Uruguayan children: Examining behavioral signatures. NeuroToxicology 2019, 73, 188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Development of the National Capacities for the Environmental Sound Management of PCBs in Uruguay. In Global Environment Facility: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.UNEP, Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants - Second Regional Monitoring Report. In GRULAC Region, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.La Guardia MJ; Hale RC; Harvey E, Detailed Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Congener Composition of the Widely Used Penta-, Octa-, and Deca-PBDE Technical Flame-retardant Mixtures. Environmental Science & Technology 2006, 40, (20), 6247–6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjödin A; Jakobsson E; Kierkegaard A; Marsh G; Sellström U, Gas chromatographic identification and quantification of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in a commercial product, Bromkal 70-5DE. Journal of Chromatography A 1998, 822, (1), 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiGangi J; Strakova J; Watson A, A survey of PBDEs in recycled carpet padding. Organohalogen Compd. 2011, 73, 2067–2070. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stapleton HM; Sjödin A; Jones RS; Niehüser S; Zhang Y; Patterson DG, Serum Levels of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Foam Recyclers and Carpet Installers Working in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology 2008, 42, (9), 3453–3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brommer S; Harrad S; Van den Eede N; Covaci A, Concentrations of organophosphate esters and brominated flame retardants in German indoor dust samples. J Environ Monitor 2012, 14, (9), 2482–2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandsma SH; de Boer J; van Velzen MJM; Leonards PEG, Organophosphorus flame retardants (PFRs) and plasticizers in house and car dust and the influence of electronic equipment. Chemosphere 2014, 116, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harrad S; Brommer S; Mueller JF, Concentrations of organophosphate flame retardants in dust from cars, homes, and offices: An international comparison. Emerging Contaminants 2016, 2, (2), 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stapleton HM; Sharma S; Getzinger G; Ferguson PL; Gabriel M; Webster TF; Blum A, Novel and High Volume Use Flame Retardants in US Couches Reflective of the 2005 PentaBDE Phase Out. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46, (24), 13432–13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Venier M; Hites RA, DDT and HCH, two discontinued organochlorine insecticides in the Great Lakes region: Isomer trends and sources. Environment International 2014, 69, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dai G-H; Liu X-H; Liang G; Gong W-W, Evaluating the exchange of DDTs between sediment and water in a major lake in North China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, (6), 4516–4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hitch RK; Day HR, Unusual persistence of DDT in some Western USA soils. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1992, 48, (2), 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manay N; Rampoldi O; Alvarez C; Piastra C; Heller T; Viapiana P; Korbut S, Pesticides in Uruguay. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2004, 181, 111–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Machado V; Mondino P; Vidal I, Impacto sociológico del uso de agrotóxicos en la fruticultura, caso del área de influencia de la Cooperativa Jumecal. In Tesis de Ingeniero Agrónomo: Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de la República, Uruguay, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu X; Zhu T; Yao B; Hu J; Hu S, Contribution of Dicofol to the Current DDT Pollution in China. Environmental Science & Technology 2005, 39, (12), 4385–4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu Z; Lin T; Hu L; Guo T; Guo Z, Atmospheric legacy organochlorine pesticides and their recent exchange dynamics in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. The Science of the total environment 2020, 727, 138408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.CODEX COMMITTEE ON PESTICIDE RESIDUES Forty-Third Session. In Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 69.European Commission, EU Pesticides database. https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/public/?event=activesubstance.selection&language=EN

- 70.Griffero L; Alcántara-Durán J; Alonso C; Rodríguez-Gallego L; Moreno-González D; García-Reyes JF; Molina-Díaz A; Pérez-Parada A, Basin-scale monitoring and risk assessment of emerging contaminants in South American Atlantic coastal lagoons. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 697, 134058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brooke DN; Crookes MJ; Quarterman P; Burns J, Environmental Risk Evaluation Report: 2-Ethylhexyl Diphenyl Phosphate (CAS no.1241-94-7). In Environment Agency, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marklund A; Andersson B; Haglund P, Screening of organophosphorus compounds and their distribution in various indoor environments. Chemosphere 2003, 53, (9), 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.