Abstract

Background

Child vaccinations are among the most effective public health interventions. However, wide gaps in child vaccination remain among different groups with uptake in most minorities or ethnic communities in Europe substantially lower compared to the general population. A systematic review was conducted to understand health system barriers and enablers to measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and human papilloma virus (HPV) child vaccination among disadvantaged, minority populations in middle- and high-income countries.

Methods

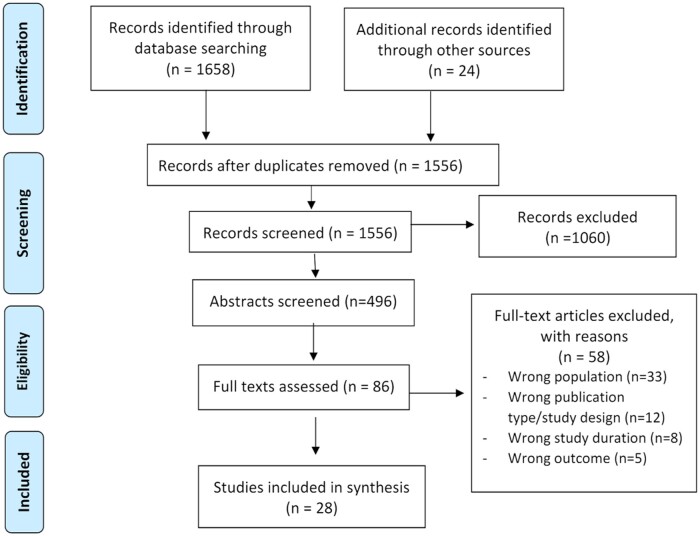

We searched Medline, Cochrane, CINAHL, ProQuest and EMBASE for articles published from 2010 to 2021. Following title and abstract screening, full texts were assessed for relevance. Study quality was appraised using Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklists. Data extraction and analysis were performed. Health system barriers and enablers to vaccination were mapped to the World Health Organization health system building blocks.

Results

A total of 1658 search results were identified from five databases and 24 from reference lists. After removing duplicates, 1556 titles were screened and 496 were eligible. Eighty-six full texts were assessed for eligibility, 28 articles met all inclusion criteria. Factors that affected MMR and HPV vaccination among disadvantaged populations included service delivery (limited time, geographic distance, lack of culturally appropriate translated materials, difficulties navigating healthcare system), healthcare workforce (language and poor communication skills), financial costs and feelings of discrimination.

Conclusion

Policymakers must consider health system barriers to vaccination faced by disadvantaged, minority populations while recognizing specific cultural contexts of each population. To ensure maximum policy impact, approaches to encourage vaccinations should be tailored to the unique population’s needs. A one-size-fits-all approach is not effective.

Introduction

Vaccinations are among the most effective public health programmes available,1 All countries in the European Economic Area (EEA) have national childhood immunization programmes, but the numbers and types of vaccines included vary across countries.2 Within countries, wide disparities in childhood vaccine uptake remain among different populations with minority ethnic and religious groups, Traveller communities, and migrants and asylum seekers often experiencing lower vaccine uptake than the general population.3

The literature includes examples of lower vaccine uptake among disadvantaged populations, including lower Meningitis B vaccine uptake among Muslim and Jewish minorities in England,4 measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine among refugees in Greece5 or HPV vaccine among Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands.6,7 This is of particular concern in the context of an increase in recent years of number of refugees and other migrants to Europe.8,9

The Immunisation Agenda 2030 (IA2030) was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to set a global vision and strategy for immunization for 2021–30.10 IA2030 emphasizes equity in vaccination by placing it as one of the core strategic pillars.10 However, barriers to access and utilization of immunization services exist, including considerable variations in policies across Europe.11

In the WHO European region, measles continues to be endemic in several countries. Progress in measles control and elimination has stalled; reported cases increased tenfold between 2016 and 2018.12 A 95% vaccine uptake rate is needed for the EU to be measles-free.13 As of 2018, only half of EU countries had reached this target. Underserved minorities and certain religious groups are repeatedly involved in measles outbreaks14 and more recently Polio outbreaks.15

The human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine is highly effective in the primary prevention of cervical cancer and other HPV-associated diseases.16 Across the EU, HPV vaccination has been gradually introduced in national immunization programmes since 2007. Today, all EU countries have HPV vaccine programmes; however, policies differ in terms of recommended vaccine age, dose number and patient costs.17 Similar to MMR, HPV vaccine uptake is considerably lower among minorities in countries where data are available, such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Greece.6,18 In other countries, uptake data are lacking among minorities, such as Roma in Slovakia and Ukrainian migrants in Poland.19,20

Extensive research exists on vaccination beliefs and attitudes among disadvantaged groups.14 However, studies exploring health system barriers and enablers specifically to MMR and HPV vaccination in children among underserved communities are limited. Identifying these barriers and enablers is essential to improve uptake among disadvantaged populations, hence reducing gaps in health disparities. As part of an EU-funded project, RIVER-EU (Reducing Inequalities in Vaccine uptake in the European region—Engaging Underserved communities), this systematic review was conducted to answer the research question: What are the health system barriers and enablers to MMR and HPV vaccination among disadvantaged populations in middle-to-high-income countries?

Methods

We searched Medline, Cochrane, CINAHL, ProQuest and EMBASE databases using a search strategy developed in consultation with a medical librarian, which combined Medical Subject Headings (MesH) terms and keywords. Search subject headings were based on four key concepts: enablers/barriers, vaccination, health system and underserved/disadvantaged populations. Supplementary material SI details the search strategy.

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Registration number: CRD42021267886). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary material SII) were followed.21 A study protocol was developed in which search strategy and study eligibility criteria were established prior to the review.

We included qualitative, quasi-experimental, ecological, observational cohort and mixed-methods studies conducted in middle- to high-income countries. Inclusion criteria included studies with parents of children (0–18 years) and adolescents (9–18 years) from disadvantaged populations, as defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) classification,3 and healthcare providers (HCP) working with these disadvantaged groups; studies focusing on health system barriers and enablers; published in English since 2010. We excluded studies that focused on vaccinations other than MMR and HPV, published before 2010, in languages other than English, conducted in low-income countries, focused on adult populations and personal level barriers and enablers. The search cut-off date was 12 December 2021.

Researcher, J.E.-H., conducted the literature search. All publications were retrieved and imported into Rayyan review manager, a free web application to support the conduct of systematic reviews,22 for screening according to the eligibility criteria. Duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (J.E.-H. and Y.G.) independently assessed titles and abstracts; abstracts were included for full-text review if they met eligibility criteria. Disagreements with regard to eligibility were resolved by discussion with the principal investigator (M.E.). Full-text publications of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed for relevance. Reference lists of selected studies were reviewed; related systematic reviews were also examined for relevant studies. Following the selection of included articles, data extraction was undertaken by two authors (J.E.-H. and Y.G.) into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Key variables extracted included: author(s), year, country, population, study aim, study design, population size, sampling strategy, setting, outcomes and recommendations. Two Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklists23 were used to assess the quality of included studies.

Using deductive content analysis, three researchers from the team searched each paper for barriers and enablers that could be conceptually linked to one of the six building blocks of the WHO’s health systems framework: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medical products, financing and leadership and governance.24 In the second stage of the analysis, the identified barriers and enablers were inductively grouped into themes within each of the building blocks. When disagreements arose with regard to which building block or theme specific barriers belonged to, a discussion between the team took place until a consensus was reached.

Results

A total of 1658 search results were identified from five databases and 24 from reference lists. After removing duplicates, 1556 titles were screened and 496 abstracts were considered eligible. Eighty-six full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 28 articles met all inclusion criteria and 58 were excluded (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study inclusion

Characteristics of included studies

Twenty-eight articles identified health system barriers and enablers to HPV and MMR vaccination among disadvantaged populations in eight countries, including the USA (n = 14), UK (n = 5), Canada (n = 3), Netherlands (n = 2), Poland (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) and Norway (n = 1), as seen in table 1. Of the 28 studies, 21 were qualitative, 4 were cross-sectional and 3 used mixed methods. Even though there is a difference in healthcare systems, almost all countries provide vaccination at no cost, except for Poland which charged for HPV until June 2023. All studies received a high CASP score, indicating high study quality. Supplementary material SIII details characteristics and quality of the included studies.

Table 1.

Studies included in the review

| Vaccine | Countries represented | Included studies Authors, Year |

|---|---|---|

| MMR | UK, Sweden, Netherlands, Canada, USA, Australia, Norway | Bell et al., 201925; Bell et al., 202028; Godoy-Ramirez et al., 201936; Harmsen et al., 201526; Kowal et al., 201546; Madlon-Kay and Smith, 202049; Mahimbo et al., 201750; Socha and Klein, 202047; Tomlinson and Redwood, 201339 |

| HPV | USA, Canada, Netherlands | Aragones et al., 201648; Bastani et al., 201135; Bruno et al., 201429; Btoush et al., 201943; Dailey and Krieger, 201744; Kepka et al., 201842; Kim et al., 201531; Greenfield et al., 201545; Lechuga et al., 201663; Miller et al., 201441; Niccolai et al., 201640; Ramanadhan et al., 202032; Rubens-Augustson, 201933; Salad et al., 201538; Vamos et al., 202134; Wilson et al., 202151 |

| MMR and HPV | Poland, UK | Ganczak et al., 202130; Jackson et al. 201727; Jackson et al., 201637 |

Health system barriers and enablers to MMR and HPV vaccination

Barriers and enablers were mapped to the six components of the WHO health system building blocks framework (table 2).

Table 2.

Predominant barriers (−) and enablers (+) to MMR and HPV vaccination mapped according to the WHO building block framework

| Barriers (−)* | MMR | HPV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service delivery | 1.1 Limited time to discuss and educate about vaccines with parents | ||

| 1.2 Limited access and clinic hours/lack of preventive care centres | |||

| 1.3 Lack of available culturally translated education materials | |||

| 1.4 Inappropriate organizational set-up or space—lack of privacy | |||

| 1.5 Lack of healthcare service continuity | |||

| 1.6 Lack of trust in healthcare system | |||

| 1.7 Hardships and challenges in navigating the system (registering in health services) | |||

| 1.8 Low attendance rates in schools when vaccine is offered | |||

| 1.9 Community-based delivery of vaccine-reduced privacy | |||

| 1.10 Fear of being questioned on legal status | |||

| Health workforce | 2.1 Interpreters lack of knowledge on vaccines | ||

| 2.2 Lack of training among GPs | |||

| 2.3 Lack of communication with HCP | |||

| 2.4 Language and communication barriers | |||

| 2.5 Lack of HCP awareness on law of immigration services | |||

| 2.6 Lack of cultural understanding among HCP | |||

| Health information system | 3.1 Lack of central immunization register | ||

| 3.2 Lack of vaccine documentation | |||

| 3.3 Lack of reminder system | |||

| Medical products | 4.1 Concerns about vaccine safety | ||

| 4.2 Belief that vaccine is ineffective | |||

|

5.1 Cost (perceived cost) of vaccination | ||

| Leadership and governance | 6.1 Lack of national policy regarding refugee vaccination | ||

| 6.2 Unclear guidelines regarding vaccination | |||

| 6.3 Feelings of discrimination | |||

| 6.4 Negligence of authorities and HCP in home country | |||

| 6.5 Unclear responsibilities regarding vaccine catch-up with general health services | |||

| Enablers (+) | MMR | HPV | |

|

1.1 Vaccine delivery is patient-friendly process | ||

| 1.2 High trust in the healthcare system in destination country | |||

|

2.1 Trustworthiness of HCP | ||

| 2.2 Good collaboration between HCP and interpreters | |||

| 2.3 Recommendation from HCP | |||

|

3.1 Effective reminders to vaccinate | ||

| 3.2 Awareness of eligibility to vaccinate | |||

|

4.1 Acceptance of vaccine | ||

| 4.2 Vaccine perceived as valuable | |||

|

5.1 Vaccine offered at no cost or subsidized | ||

|

6.1 Enforcement of child immunization by authorities | ||

| 6.2 Vaccination encouraged by religion and social norms | |||

Shading indicates barrier applicable to specific vaccine.

Building block 1: service delivery

MMR and HPV vaccination barriers mostly involved service delivery. HCPs and parents cited limited time for vaccine discussion as a hurdle.25–31 US Black, Latino and Brazilian minorities expressed concerns about community-based delivery of HPV, due to privacy issues, inappropriate setting to ask questions and discomfort engaging with unknown HCPs.32 Minorities faced challenges navigating the health system to receive vaccinations,25,27,30,33 with UK HCPs noting language barriers as an additional obstacle.28 Minorities often misunderstood the process of registering newborns at their GP practice, assuming it was automatic if the mother was already registered.25,28

Geographic distance to clinics and limited primary health care access posed challenges for vaccine accessibility.26,28,33 US HCPs serving minorities reported insufficient preventive care centres offering HPV vaccines29 and restricted clinic hours.34 Other disadvantaged populations lacked awareness of where to access HPV vaccines.35 Traveller communities faced barriers to accessing school-based immunizations, such as HPV, particularly for home-schooled or migratory girls.27

Undocumented migrants hesitated to vaccinate children due to fears of questioning their legal status.36 Despite some groups reporting greater trust in the healthcare system in their new country of residency, many still expressed a lack of trust in the healthcare system as a barrier to vaccination.25,30,36–38

Minorities expressed the lack of culturally appropriate translated educational materials available for both MMR and HPV vaccines, resulting in a lack of awareness and knowledge regarding the vaccine and ultimately parents’ decision to vaccinate.26,28,30,31,35,39–45 The Somali minority in the Netherlands reported that their major information source on HPV vaccines was peers, rather than formal leaflets or printed materials.38

Some populations indicated that a lack of trust in the system was a barrier to vaccination. Others indicated high levels of trust in the healthcare system of their residing country in comparison to their country of origin, facilitating their decision to vaccinate since they perceived vaccines were of better quality.27,30,46 Ukrainian migrants in Poland expressed greater trust in mandatory vaccine delivery, including MMR, in Polish healthcare, indicating it was a patient-friendly process.30 Hispanic, Somali and Eritrean parents in the USA reported high trust in physicians when seeking information and recommendations regarding HPV vaccination, much higher than from family and friends.45

Building block 2: health workforce

Language barriers hindered patient-provider communication, impacting vaccination decisions.25–28,34,37,38,46,47 Lack of HCP recommendation was a major reason for non-vaccination.33,40,43,45,48 Studies in the USA with parents from low-income minorities reported their decision to give the HPV vaccine was highly reliant on the HCPs recommendations.40,45

Interpreters were sometimes reported as having limited vaccine knowledge, which made answering questions and adequate translation difficult.49 HCPs lacked training around vaccination needs were not always familiar with immigrant service polices and reported inadequate cultural understanding, making it difficult to understand the population’s needs and offer practical recommendations.36–38,50 Often HCPs were uncomfortable bringing up HPV vaccine due to the sensitivity and parents’ unwillingness to discuss sex-related issues.29,44 They expressed concerns about offending parents due to the link between HPV vaccine and sexual transmission.29

Intrinsic HCPs characteristics, like trustworthiness32,46 and good collaboration with interpreters working with minorities,49 were vaccine enablers.

Building block 3: health information systems

HCPs reported a lack of vaccination documentation for immigrants and refugees as a barrier. At an institutional level, HCPs faced challenges in determining which vaccines had been administered25 due to inadequate records on immunization history,37 and lack of a central immunization register.36,47,50 This was noted in studies dealing with minority, migrant and refugee populations in the UK, Australia, Sweden, Norway and the USA.

Effective reminder and recall systems were a vaccine enabler to MMR vaccination, as reported by English Gypsies, European Roma and Irish Travellers in the UK.27 Face-to-face communication and reminders from general practitioners were considered even more effective to reaching communities and gaining their trust.28

Building block 4: medical products

Perceived safety and efficacy of vaccines greatly affect uptake and acceptance levels. There were mixed findings in terms of parent’s perceptions and attitudes towards vaccination. Undocumented immigrant parents and HCPs in Sweden reported that parents gladly accepted routine child vaccinations.36 Immigrant parents in the Netherlands held positive views on MMR vaccination safety, importance and effectiveness.26 UK Gypsies, Travellers and Roma parents emphasized the protective benefits of MMR immunization, deeming minor side effects or brief discomfort insignificant.27 However, specifically among the Scottish Showpeople, a community comprised travelling show, circus and fairground families, there were great fears towards MMR vaccine safety.37

Some minorities perceived MMR vaccination as unnecessary and ineffective.28 Polish and Romanian minorities in England, along with Somali mothers in the UK, hesitated to vaccinate due to concerns about a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.25,39 Similar fears and concerns surrounding HPV vaccine safety.29,41 Parents, particularly Somali and Hispanic immigrants in the USA, expressed worries about the implication of HPV vaccine on their child’s health and sexual behaviour, with concerns about the potential encouragement of promiscuity.43–45 Conservative minorities, including Somali mothers in the Netherlands, who do not believe multiple sexual partners or premarital sex socially or culturally acceptable, considered the HPV vaccine unnecessary, feeling they were not susceptible to HPV.38

Building block 5: financing

Perceived costs, particularly for HPV vaccination, pose a significant barrier.28–31,33,34,37,42,50,51 HCPs working with minorities in the USA noted the high cost of HPV vaccine as a barrier to recommending it.29 For populations facing daily socio-economic challenges, vaccination was not a priority amidst competing demands.28 Offering MMR and HPV vaccinations for free or subsidized is reported as a major enabler by both parents and providers.47

Building block 6: leadership and governance

Lack of national policy and guidelines for refugees, particularly regarding catch-up vaccines, hinders child vaccination.50 Migrant populations in Poland felt neglected by authorities and HCPs in their home country regarding vaccinations.30 HCPs expressed a lack of clarity regarding who is responsible for ensuring the completion of catch-up immunization for newly arrived refugees. Inadequate referral pathways for refugees to health services upon resettlement further exasperated the confusion on whose responsibility it is to provide catch-up vaccines.50

Minority, migrant and Traveller communities reported feelings of discrimination from workers in the health system due to their status. Polish, Romanian and Traveller communities reported experiences of discrimination from receptionists in general practitioners’ offices when trying to register for services or make appointments.25,27

Including child vaccinations, like MMR, for migrant children in the national vaccination schedule can boost uptake, as seen in Norway where clear guidelines facilitated vaccination.47

Cultural and religious support plays an important role in encouraging vaccination. In the Netherlands religiously framed messages (in this instance Islam) positively influenced Turkish and Moroccan parents’ decision to vaccinate, viewing it as beneficial for the child’s health.26 Similarly, Somali mothers in the Netherlands believed that Islam supported preventive care but felt HPV vaccine was unnecessary due to perceived low susceptibility based on religious norms prohibiting premarital sex.38

Discussion

This review explores health system barriers and enablers to childhood MMR and HPV vaccines among disadvantaged, minority or underserved populations. Twenty-eight studies were identified that examined MMR and HPV vaccination among children in middle- to high-income countries. Previous systematic reviews have investigated parental factors impacting childhood vaccination among general population groups.52,53 Another review examined vaccine coverage levels, accessibility and underlying factors affecting disadvantaged populations but did not include HPV.9 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review concentrating on barriers and enablers to MMR and HPV vaccinations in disadvantaged, minority or underserved children (age 0–18 years).

The WHO health system building blocks framework provides a comprehensive approach to assessing health system barriers and enablers to MMR and HPV vaccinations in disadvantaged communities. These blocks, influenced by numerous factors, are strongly interlinked. At the health system level, some barriers and enablers affecting MMR and HPV uptake rates among disadvantaged population groups are universal, regardless of the specific vulnerable population. These include service delivery barriers (limited time for HCP to offer and discuss vaccine,25,27–31 geographic distance,26,28,33 lack of translated culturally appropriate materials, difficulties navigating healthcare system26,28,30,31,35,39–41,43–45,54) and healthcare workforce barriers (language barriers and poor communication skills,25–28,34,37,38,46,47 financial costs28–31,33,34,37,42,50,51 and feelings of discrimination.25,27) While barriers, such as lack of time and geographic distance, are also likely to affect general populations, disadvantaged groups are disproportionately affected.55,56 Health policymakers should recognize that minimizing these barriers could positively impact vaccination programmes across contexts, irrespective of the specific vaccine or population group. Barriers related to ease and access to service, translated services and materials, healthcare workforce characteristics and financial costs are not unique to vaccine services and are observed across health services when treating underserved populations, such as diabetes or general healthcare57,58 Minimizing these barriers at the system level should be a priority for policymakers, yielding benefits beyond a single programme.

However, certain barriers are specific to particular vaccines and populations, influenced by cultural and social norms, directly affecting the vaccine’s acceptability. For example, conservative minorities may view the HPV vaccine as unnecessary if a single lifetime sexual partner is the widespread norm. Other groups feared that giving HPV vaccine would encourage sexual activity and promiscuity.38 HCPs serving these populations need training to address these beliefs and provide culturally appropriate information. Policymakers should recognize the specificity of these vaccines and have an in-depth understanding of the social and cultural circumstances of the populations in their jurisdiction. Tailoring approaches to encourage vaccination based on the unique needs of each population is crucial, as a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective in these circumstances. This approach has been used effectively in different countries, where the HPV vaccine was promoted as protecting against cancer, rather than associating it with a sexually transmissible infection.59,60

In a world of increasing migration, the lack of inter-operable guidelines and data contributes to a lack of clarity when providing catch-up immunization or monitoring vaccine programmes. This may result in administering unnecessary vaccine doses or missed opportunities for immunization for migrants and refugees. While some countries have guidance for HCP on dealing with unknown or incomplete immunizations for individuals lacking records,61 it is crucial to extend and standardize such guidance. In cases where populations, such as refugees, are immunized by dedicated services outside of the national immunization programmes, coordination between the two is essential to maintain updated records and ensure vaccines are not missed. A coordinated programme across countries is especially fundamental in the EU where citizens move across borders, and refugees continuously arrive from diverse countries and continents.62

Based on the reviews’ findings, our recommendations to promote MMR and HPV vaccination among disadvantaged, minority populations include ensuring educational materials and health services are provided in the minority population’s native language and in a culturally appropriate manner, by health professionals who have received adequate cultural competence training. Health systems need to develop simple, clear guidelines to help new immigrant and minority groups access the new healthcare system. Vaccinations need to be made widely available, easily accessible and at no cost (or highly subsidized) to the community. Furthermore, we recommend health systems set up automatic reminders and recall systems to facilitate vaccination processes. Table 3 further details and maps the recommendations to the WHO building blocks.

Table 3.

Recommendations for strategies in each of the six building blocks to promote MMR and HPV vaccination among disadvantaged, minority populations

| WHO building block | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Service delivery |

|

| Workforce |

|

| Health information system |

|

| Medical products | Develop culturally tailored education programmes to increase awareness regarding vaccine safety and effectiveness among target populations. |

| Financing | Offer free or subsidized MMR and HPV vaccination. |

| Governance/leadership | Develop clear standardized national and international guidelines on MMR and HPV vaccinations for refugee and migrant populations. |

Study strengths and limitations

One key strength of the review is its inclusion of perspectives from multiple key stakeholders (parents, HCPs and policymakers), and not just one group. This provides a comprehensive understanding of barriers and enablers to vaccination, and picture and not just one piece of the puzzle. Focusing on MMR and HPV vaccines, rather than vaccination in general, has allowed for the identification of vaccine and context-specific factors, as well as more generic and universal ones. This dual perspective is crucial for developing interventions and strategies that effectively address the diverse needs of the target population.

A limitation is the inclusion of only English-language publications. Many studies included were conducted in the USA, where the healthcare system is organized differently than in Europe and where disadvantaged minority populations are unique and differ greatly in terms of culture, ethnic and religious background from disadvantaged populations in Europe. Barriers and enablers of these populations might not necessarily be representative of other disadvantaged minorities in other parts of the world. However, we did not want to limit our search to only studies in Europe because some of the enablers and barriers relevant to disadvantaged populations in other parts of the world could be relevant to European disadvantaged groups as well. While similar themes emerged, it is important to recognize that a one-size-fits-all approach might not be successful in such diverse population groups where other aspects and characteristics need to be considered. Health professionals and policymakers need to consider the specific cultural context of the target populations they are working with when implementing vaccine programmes.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jumanah Essa-Hadad, Department of Population Health, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

Yanay Gorelik, Department of Population Health, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

Johanna Vervoort, Department of Health Sciences-Global Health Unit, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Danielle Jansen, Department of Primary- and Long-term Care, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Michael Edelstein, Department of Population Health, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Author contributions

This review was conceived by M.E., J.V. and D.J. The review protocol was written by J.E.-H. with comments from M.E., J.V. and D.J. Screening data extraction and quality assurance were undertaken by J.E.-H. and Y.G. Review synthesis was undertaken by J.E.-H. and Y.G. with advice from M.E. The manuscript was drafted by J.E.-H. with comments from all co-authors.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No: 964353, call SC1-BHC-33-2020 Addressing low vaccine uptake.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not applicable to this study since it was a systematic review. This study did not have human participants.

Key points.

Identifying health system barriers and enablers to childhood vaccination is essential to improve uptake rates among disadvantaged populations, hence reducing gaps in health disparities.

At the health system level, some barriers and enablers affecting MMR and HPV uptake rates among disadvantaged population groups are universal, regardless of a specific vulnerable population, including service delivery barriers (limited time for HCP to offer and discuss vaccine, geographic distance, lack of translated culturally appropriate materials, difficulties navigating health care system, healthcare workforce barriers (language barriers and poor communication skills, financial costs and feelings of discrimination).

Some barriers are specific to certain vaccines and populations and are highly affected by cultural and social norms, which can have a direct impact on the populations’ acceptability of the specific vaccine.

To ensure maximum policy impact the approaches to encourage vaccination should be tailored to the unique needs of the population at hand. A one-size-fits-all approach in these circumstances is not effective.

Data availability

Data are available on request.

References

- 1. Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:140–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Vaccine Schedules in All Countries in the EU/EEA. 2022. Available at: https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/ (20 May 2023, date last accessed).

- 3. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Vaccine Uptake in the General Population: NICE Guidelines. 2022. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng218 (21 May 2023, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 4. Tiley KS, White JM, Andrews N, et al. Equity of the Meningitis B vaccination programme in England, 2016–2018. Vaccine. 2022;40:6125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mellou K, Silvestros C, Saranti-Papasaranti E, et al. Increasing childhood vaccination coverage of the refugee and migrant population in Greece through the European Programme Philos, April 2017 to April 2018. Euro Surveill 2019;24(27). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Munter AC, Klooster TMS, van T, van Lier A, et al. Determinants of HPV-vaccination uptake and subgroups with a lower uptake in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2021;21:1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Lier A, van de Kassteele J, de Hoogh P, et al. Vaccine uptake determinants in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Organization of Migration 2019. Available at: https://www.iom.intkey-migration-terms (10 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 9. Ekezie W, Awwad S, Krauchenberg A, et al. Access to vaccination among disadvantaged, isolated and difficult-to-reach communities in the WHO European Region: a systematic review. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10(7):1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. Immunization Agenda 2030: Leave No One Behind. 2020. Available at: ia2030-draft-4-wha_b8850379-1fce-4847-bfd1-5d2c9d9e32f8.pdf (who.int) (25 June 2023, date last accessed).

- 11. Ravensbergen SJ, Nellums LB, Hargreaves S, Stienstra Y, Friedland JS; ESGITM Working Group on Vaccination in Migrants. National approaches to the vaccination of recently arrived migrants in Europe: a comparative policy analysis across 32 European countries. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019;27:33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zimmerman LA, Muscat M, Singh S, et al. Progress toward measles elimination—European region, 2009-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Health Organization. Global Measles and Rubella Stratetic Plan: 2012-20. 2012. Available at: 9789241503396_eng.pdf (who.int) (21 May 2023, date last accessed).

- 14. Fournet N, Mollema L, Ruijs WL, et al. Under-vaccinated groups in Europe and their beliefs, attitudes and reasons for non-vaccination; two systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. Detection of Circulating Vaccine Derived Polio Virus 2 (cVDPV2) in Environmental Samples—The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON408 (1 June 2023, date last accessed).

- 16. Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction—the first five years. Vaccine 2012;30 Suppl 5:F139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nguyen-Huu NH, Thilly N, Derrough T, Sdona E, Claudot F, Pulcini C, et al. ; HPV Policy working group Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage, policies, and practical implementation across Europe. Vaccine 2020;38:1315–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giambi C, Del Manso M, Dalla Zuanna T, Riccardo F, Bella A, Caporali MG, et al. ; CARE working group for the National Immunization Survey. National immunization strategies targeting migrants in six European countries. Vaccine 2019;37:4610–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chernyshov PV, Humenna I.. Human papillomavirus: vaccination, related cancer awareness, and risk of transmission among female medical students. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2019;28:75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duval L, Wolff FC, McKee M, Roberts B.. The Roma vaccination gap: evidence from twelve countries in Central and South-East Europe. Vaccine 2016;34:5524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A.. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Critical Appraisal Skills Program Checklist. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2018. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (28 May 2022, date last accessed).

- 24. World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: a Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. Vol. 35. World Health Organization. 2010. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bell S, Edelstein M, Zatoński M, et al. “I don’t think anybody explained to me how it works”: qualitative study exploring vaccination and primary health service access and uptake amongst Polish and Romanian communities in England. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harmsen IA, Bos H, Ruiter RAC, et al. Vaccination decision-making of immigrant parents in the Netherlands; a focus group study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jackson C, Bedford H, Cheater FM, et al. Needles, Jabs and Jags: a qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to child and adult immunisation uptake among Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bell S, Saliba V, Ramsay M, Mounier-Jack S.. What have we learnt from measles outbreaks in 3 English cities? A qualitative exploration of factors influencing vaccination uptake in Romanian and Roma Romanian communities. BMC Public Health 2020;20:381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bruno DM, Wilson TE, Gany F, Aragones A.. Identifying human papillomavirus vaccination practices among primary care providers of minority, low-income and immigrant patient populations. Vaccine 2014;32:4149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ganczak M, Bielecki K, Drozd-Dąbrowska M, et al. Vaccination concerns, beliefs and practices among Ukrainian migrants in Poland: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim K, Kim B, Choi E, et al. Knowledge, perceptions, and decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among Korean American women: a focus group study. Womens Health Issues 2015;25:112–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramanadhan S, Fontanet C, Teixeira M, et al. Exploring attitudes of adolescents and caregivers towards community-based delivery of the HPV vaccine: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rubens-Augustson T, Wilson LA, Murphy MS, et al. Healthcare provider perspectives on the uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine among newcomers to Canada: a qualitative study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019;15:1697–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vamos CA, Kline N, Vázquez-Otero C, et al. Stakeholders’ perspectives on system-level barriers to and facilitators of HPV vaccination among Hispanic migrant farmworkers. Ethn Health 2022;27:1442–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bastani R, Glenn BA, Tsui J, et al. Understanding suboptimal human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among ethnic minority girls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:1463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Godoy-Ramirez K, Appelqvist E, Lindstrand A, et al. Exploring childhood immunization among undocumented migrants in Sweden—following qualitative study and the World Health Organizations Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Public Health 2019;171:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jackson C, Dyson L, Bedford H, et al. UNderstanding uptake of Immunisations in TravellIng aNd Gypsy communities (UNITING): a qualitative interview study. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salad J, Verdonk P, de Boer F, Abma TA.. “A Somali girl is Muslim and does not have premarital sex. Is vaccination really necessary?” A qualitative study into the perceptions of Somali women in the Netherlands about the prevention of cervical cancer. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tomlinson N, Redwood S.. Health beliefs about preschool immunisations: an exploration of the views of Somali women resident in the UK. Divers Equal Health Care. 2013;10:101–13. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/health-beliefs-about-preschool-immunisations/docview/2670184921/se-2. [Google Scholar]

- 40. References 40–63 are available in the Supplementary File IV.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.