Abstract

Background

There is still no specific real-world data regarding the clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the elderly with liver cancer. Our study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors between patients aged ≥ 65 years and the younger group, while exploring their differences in genomic background and tumor microenvironment.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted at two hospitals in China and included 540 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for primary liver cancer between January 2018 and December 2021. Patients’ medical records were reviewed for clinical and radiological data and oncologic outcomes. The genomic and clinical data of patients with primary liver cancer were extracted and analyzed from TCGA-LIHC, GSE14520, and GSE140901 datasets.

Results

Ninety-two patients were classified as elderly and showed better progression-free survival (P = 0.027) and disease control rate (P = 0.014). No difference was observed in overall survival (P = 0.69) or objective response rate (P = 0.423) between the two age groups. No significant difference was reported concerning the number (P = 0.824) and severity (P = 0.421) of adverse events. The enrichment analyses indicated that the elderly group was linked to lower expression of oncogenic pathways, such as PI3K-Akt, Wnt, and IL-17. The elderly had a higher tumor mutation burden than younger patients.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that immune checkpoint inhibitors might exhibit better efficacy in the elderly with primary liver cancer, with no increased adverse events. Differences in genomic characteristics and tumor mutation burden may partially explain these results.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03417-3.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Elderly, Primary liver cancer, Efficacy, Safety

Introduction

Hepatocellular malignancy is one of the main causes of death worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN statistics in 2020, the incidence of primary liver cancer (PLC) ranked sixth among malignant tumors with 905,677 new cases worldwide, and mortality ranked third with 830,180 liver cancer-related deaths [1]. PLC is the fourth most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China [2]. Most patients are diagnosed at either an intermediate or an advanced stage when radical treatment options are no longer suitable [3]. After consideration of locoregional treatment, systemic therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is the preferred treatment option [4].

Over the past few decades, worldwide PLC prevalence has considerably increased in elderly patients due to aging of the world population [5]. It is necessary to recommend treatment options with better efficacy and fewer side effects for elderly patients. ICIs are considered the most substantial novelty concerning cancer treatment strategies and have been used in PLC patients within the last few years [4]. The safety profile of ICIs compares favorably to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, with no known cumulative toxicity [6]. In this context, ICIs represent an attractive option for older patients.

Immunosenescence is a process of immune dysfunction that occurs with age and leads to changes in the immune function of the elderly, raising concern regarding the efficacy and safety of ICIs in elderly patients [7]. In the preclinical setting, age-related immune dysfunction has been shown to alter ICI efficacy [8]. The proportion of older adults included in clinical trials evaluating ICI immunotherapy for liver cancer remains low [9, 10]. It is mostly limited to those with Child-Pugh class A disease without previous systemic therapy [11]. Therefore, the clinical activity of ICIs in elderly patients with PLC is limited by their underrepresentation in immunotherapy-related clinical trials and the selection of fit older patients in these trials [12]. A few real-life setting retrospective studies were in favor of similar [13–15] or even better [16, 17] outcomes among older patients treated with ICIs. However, there is still no specific data on the elderly with PLC receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors in the real world.

We, therefore, conducted a large retrospective analysis to compare the safety and efficacy of ICIs in patients aged ≥ 65 years (i.e., the elderly group) and those aged < 65 years (i.e., the young group) in a multicenter and real-life cohort of patients with PLC. Furthermore, we tried to explore the differences in genomic characteristics and tumor microenvironment (TME) between the mentioned age groups.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

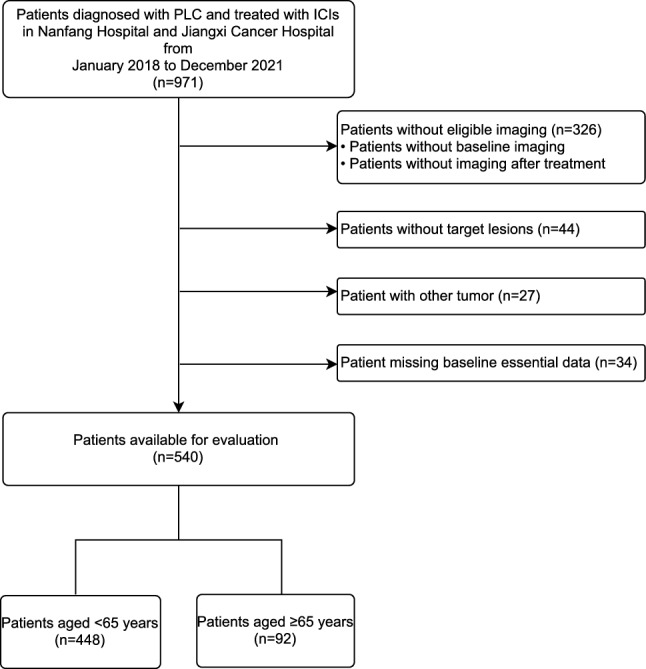

This multicenter retrospective study was conducted in two hospitals in China: Nangfang Hospital, Guangzhou, and Jiangxi Cancer Hospital, Nanchang. We retrospectively reviewed the data of patients diagnosed with PLC and treated with ICIs between January 2018 and December 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histologically or clinically diagnosed PLC, (2) treated with at least one dose of ICI, and (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) ≤ 2 points. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) missing baseline data; (2) without target lesions based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1; (3) lack of required imaging examination before and after treatment; and (4) presence of additional tumors other than PLC. A flowchart of the patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Oncologic outcomes, patient history, laboratory results, and radiological data were collected from patients’ medical records.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the patient selection process in the study. PLC, primary liver cancer; ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor

The baseline was defined as the start of ICI treatment. All patients in our study returned for follow-up computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was performed according to their immunotherapy cycles. The study design was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (approval number: NFEC-2021-048), and it complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for obtaining informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective study design.

Data collection

Baseline data, including information on age, sex, ECOG-PS, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), Child-Pugh class, hepatitis B virus (HBV), intrahepatic metastasis, number of distant metastatic sites, and treatment line of ICI, were collected from the electronic medical record system at the start of ICI treatment for each enrolled patient. Elderly patients were defined as those aged 65 years or more. The United Nations agreed that the term elderly refers to people over 65 years, and previous studies used 65 years as the cut-off for the definition of “elderly” [1, 18, 19].

The tumor response to the treatment was assessed according to the RECIST version 1.1 [20]. The objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR) and those who achieved CR, PR, or stable disease (SD) as the best overall response, respectively. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the initiation of ICI treatment to disease progression or death from any cause or to the last contact with the patient. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from treatment initiation to death from any cause or to the last contact. Side effects were recorded at every visit and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0.

Statistical analysis for clinical data

The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used to assess data normality. Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and those with non-normal distribution are expressed as median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables with normal and non-normal distribution, the t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare the differences between groups. Either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used as appropriate to compare the categorical data. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. A multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to examine the effects on PFS and OS after adjustment for baseline prognostic parameters. Besides, we implemented propensity score matching (PSM) to balance the baseline characteristics of the two groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at a two-sided P value of < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the R software (4.1.2).

Data acquisition and analysis from TCGA and GEO

We screened 370 patients with liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) with known age and complete transcriptome profiles from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to analyze the differences in genomic characteristics between young (n = 221) and old (n = 149) patient groups. Microarray and clinicopathological data, including GSE14520 and GSE140901, were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. GSE14520 contained 247 samples from Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) samples from Chinese patients, of which 212 belonged to the young group and 30 to the elderly group. GSE140901 contained 24 HCC samples from Chinese patients (17 < 65 years old and 7 ≥ 65 years old) treated with ICI-based therapy.

We used limma (R package) and edgeR (R package) to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), adjusted P value < 0.05 and |log2 fold-change| > 1 in the GEO datasets and TCGA-LIHC data, respectively. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed to explore DEG-associated cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes. Furthermore, we performed the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis to elucidate the potential signaling pathways associated with DEGs.

The corresponding somatic alteration information of the LIHC cohort was obtained from the TCGA dataset. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) was defined as the number of DNA mutations per megabase (muts/Mb) in the tumor coding genome. The “maftools” R package [21] was used to calculate the number of somatic non-synonymous point mutations within each sample and compare the TMB between the old and young groups.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics and baseline demographics are presented in Table 1. A total of 540 patients with PLC treated with ICIs were enrolled. The mean age of the elderly patients was 69.9 years. The characteristics were well balanced between the two groups, except for the AFP level (P = 0.009) and HBV status (P < 0.001). Patients aged ≥ 65 years had lower median AFP levels than younger patients (44.5 ng/ml vs. 267 ng/ml). On the contrary, younger patients more frequently experienced HBV infection (89.1% vs. 69.6%). Immunotherapy was used as systemic first‐, second‐, or more than third‐line therapy in 427 (79.1%), 98 (18.1%), and 15 (2.78%) patients, respectively. A significant number of elderly patients had Child–Pugh class B (n = 25; 27.2%).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| All | Aged < 65 years | Aged ≥ 65 years | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 540 | N = 448 | N = 92 | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (11.9) | 49.0 (9.55) | 69.9 (4.32) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.199 | |||

| Male | 471 (87.2) | 395 (88.2) | 76 (82.6) | |

| Female | 69 (12.8) | 53 (11.8) | 16 (17.4) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | 0.383 | |||

| 0 | 309 (57.2) | 262 (58.5) | 47 (51.1) | |

| 1 | 210 (38.9) | 168 (37.5) | 42 (45.7) | |

| 2 | 21 (3.89) | 18 (4.02) | 3 (3.26) | |

| BCLC stage, n (%) | 0.075 | |||

| A | 10 (1.85) | 7 (1.56) | 3 (3.26) | |

| B | 116 (21.5) | 90 (20.1) | 26 (28.3) | |

| C | 414 (76.7) | 351 (78.3) | 63 (68.5) | |

| AFP, ng/ml | ||||

| Median [range] | 188 [7.90;5341] | 267 [8.99;7899] | 44.5 [4.97;1766] | 0.009 |

| AFP ≥ 20 ng/ml | 371 (69.3) | 315 (70.9) | 56 (61.5) | 0.099 |

| Child-Pugh Class, n (%) | 0.827 | |||

| A | 399 (73.9) | 332 (74.1) | 67 (72.8) | |

| B | 138 (25.6) | 113 (25.2) | 25 (27.2) | |

| C | 3 (0.56) | 3 (0.67) | 0 (0.00) | |

| HBV, n (%) | 463 (85.7) | 399 (89.1) | 64 (69.6) | < 0.001 |

| Intrahepatic metastasis, n (%) | 405 (75.0) | 340 (75.9) | 65 (70.7) | 0.355 |

| Number of distant metastatic sites, n (%) | 0.861 | |||

| 1 | 173 (32.0) | 145 (32.4) | 28 (30.4) | |

| 2 | 111 (20.6) | 93 (20.8) | 18 (19.6) | |

| Treatment line of ICI, n (%) | 0.199 | |||

| 1 | 427 (79.1) | 358 (79.9) | 69 (75.0) | |

| 2 | 98 (18.1) | 80 (17.9) | 18 (19.6) | |

| ≥ 3 | 15 (2.78) | 10 (2.23) | 5 (5.43) | |

Categorical values are shown as n (%). Continuous variables are shown as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range]

ECOG PS eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, BCLC stage barcelona clinic liver cancer stage, AFP alpha-fetoprotein, HBV hepatitis B virus, ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, n, number

Efficacy

The efficacy of ICI according to age is summarized in Table 2. In the elderly group, none of the patients achieved CR, and 11 (12.0%) of them achieved PR. A total of 64 (69.6%) patients showed SD, and 16 (17.4%) had PD. Among the younger patients, 72 (16.1%) and 237 (52.9%) achieved PR and SD, respectively. In addition, 139 (31.0%) patients had PD. Concerning tumor response, the ORR tended to be lower in elderly patients (12.1% vs. 16.1%, P = 0.423), but the DCR was higher in elderly patients (82.4% vs. 69.0%, P = 0.014).

Table 2.

Treatment Outcome, Best Response by RECIST v1.1

| All | Aged < 65 years | Aged ≥ 65 years | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 540 | N = 448 | N = 92 | ||

| Best response, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| PR | 83 (15.4) | 72 (16.1) | 11 (12.0) | |

| SD | 301 (55.7) | 237 (52.9) | 64 (69.6) | |

| PD | 155 (28.7) | 139 (31.0) | 16 (17.4) | |

| NE | 1 (0.19) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.09) | |

| ORR, n (%) | 83 (15.4) | 72 (16.1) | 11 (12.1) | 0.423 |

| DCR, n (%) | 384 (71.2) | 309 (69.0) | 75 (82.4) | 0.014 |

| PFS, days median (95% CI) | 193 (176–218) | 182 (168–204) | 258 (210–337) | |

| OS, days median (95% CI) | 569 (510–715) | 569 (578–799) | 482 (415–NA) |

Categorical values are shown as n (%)

RECIST response evaluation criteria in solid tumors, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease, NE not evaluable, ORR overall response rate, DCR disease control rate, PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, n number, CI confidence interval

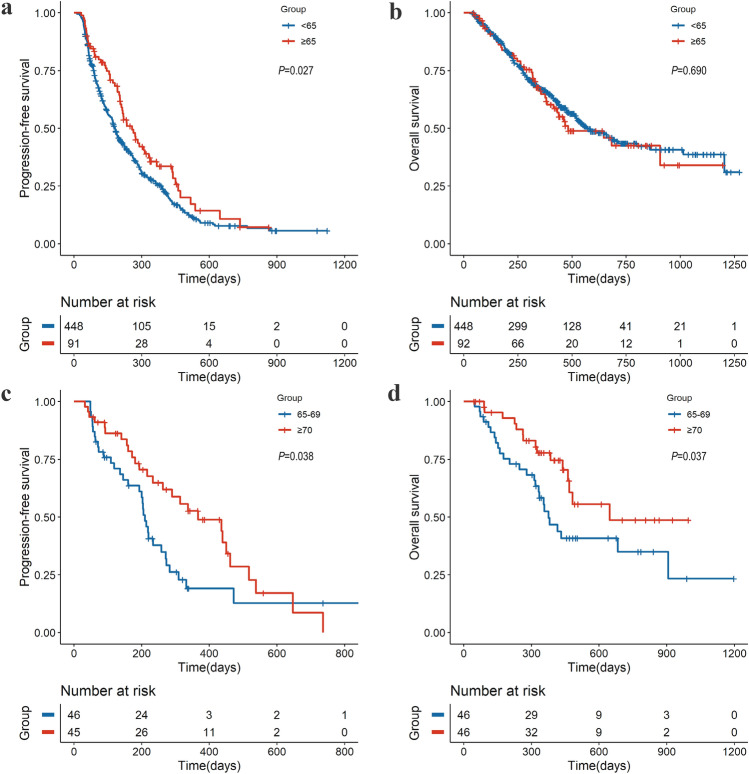

The median PFS for elderly patients was 258 days (95% confidence interval [CI] 210–337) versus 182 days (95% CI 168–204) in patients aged < 65 years (hazard rate [HR], 0.74; 95% CI 0.57–0.94; P = 0.027) (Fig. 2a and Table 2). The median OS after the beginning of immunotherapy in elderly patients was 482 days (95% CI 415-NA) versus 569 days (95% CI 578–799) in younger patients (HR, 1.07; 95% CI 0.76–1.51; P = 0.69) (Fig. 2b and Table 2). The 92 elderly patients aged ≥ 65 years were divided into two subgroups: patients aged < 70 and ≥ 70 years. According to subgroups of aged 65–69 and ≥ 70 years old, the median PFS was 210 and 367 days, respectively (HR, 0.59; 95% CI 0.36–0.99; P = 0.038) (Fig. 2c). The median OS was 376 days (95% CI 332-NA) versus 647 days (95% CI 468-NA) for the subgroups (HR, 0.51; 95% CI 0.28–0.95; P = 0.037) (Fig. 2d). As shown in supplementary Table 1, after adjusting for the possible confounding factors, age ≥ 65 years was significantly associated with PFS (HR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.57–0.99; P = 0.044) but not with OS (HR, 1.11; 95% CI 0.78–1.57; P = 0.575). The results of the multivariable analysis of OS and PFS by the Cox model after PSM were consistent (supplementary Table 2 and supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival and overall survival by age group. Kaplan–Meier estimates according to age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years) for patients treated with ICI for a progression-free survival and b overall survival. Kaplan–Meier estimates according to age (65–69 years and ≥ 70 years) for elderly patients treated with ICI for c progression-free survival and d overall survival. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; CI, confidence interval

Safety and tolerability

To examine the association between age and ICI safety, we compared the incidence rates and grades of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) between the elderly and young groups (Table 3). No significant difference was reported between the two age groups regarding the number (P = 0.824) and severity (P = 0.421) of TRAEs. The most frequent (> 3%) TRAEs of any grade in the elderly group were cardiac (6.5%), skin (4.3%), endocrine (4.3%), and hepatic (3.3%). The most common TRAEs in younger patients were skin (8.0%) and endocrine (6.9%).

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events

| Adverse event, n (%) | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged < 65 years (N = 448) | Aged ≥ 65 years (N = 92) | P value | Aged < 65 years (N = 448) | Aged ≥ 65 years (N = 92) | P value | |

| Number of AEs/patients | 0.824 | 0.421 | ||||

| 0 | 344 (76.8) | 74 (80.4) | 428 (95.5) | 91 (98.9) | ||

| 1 | 86 (19.2) | 15 (16.3) | 16 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 18 (4.0) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Skin | 36 (8.0) | 4 (4.3) | 0.277 | 7 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.553 |

| Endocrine | 31 (6.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.487 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.575 |

| Hepatic | 12 (2.7) | 3 (3.3) | 0.729 | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.446 |

| Gastrointestinal | 8 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0.999 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Pulmonary/respiratory | 10 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.700 | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1 (0.2) | 2 (2.2) | 0.077 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.077 |

| Injection reation | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Renal | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.999 |

| Hematological | 13 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.139 | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.455 |

| Cardiac | 11 (2.5) | 6 (6.5) | 0.052 | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.052 |

Categorical values are shown as n (%)

AEs adverse events, n number

Genomic landscape and TME in the two age groups

Identification of DEGs

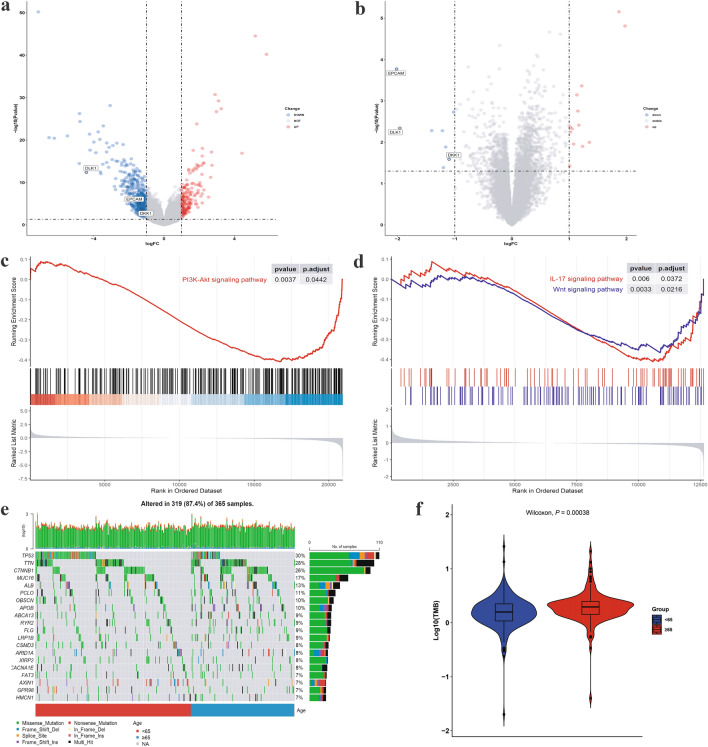

DEGs between elderly and younger groups were screened out in the TCGA-LIHC, GSE14520, and GSE140901 datasets. A total of 614 DEGs were found in TCGA-LIHC, 21 in GSE14520, and 7 in GSE140901 (Fig. 3a–b, S1). Among them, 176, 13, and 4 genes were upregulated in the TCGA-LIHC, GSE14520, and GSE140901 datasets, respectively. Additionally, 438, 8, and 3 genes were downregulated in the TCGA-LIHC, GSE14520, and GSE140901 datasets, respectively. Finally, five overlapping DEGs (metallothionein 1 M, MT1M; epithelial cell adhesion molecule, EPCAM; delta-like homologue 1, DLK1; dickkopf-1, DKK1; and paternally expressed 3, PEG3) were identified in the TCGA-LIHC and GSE14520 databases. GSE140901 has expression profiling using the nCounter PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel from an immunotherapy cohort, showing seven DEGs between age groups.

Fig. 3.

Genomic landscape in two groups. a–b Volcano plots of DEGs from TCGA-LIGC and GSE14520. c PI3K-Akt signaling pathway of KEGG was recognized as downregulated pathway in the elderly group from TCGA-LIHC identified by GSEA. d Two downregulated pathways associated with DEGs of KEGG in the elderly group from GSE14520 identified by GSEA. e Mutation landscape of the young and old groups. The patients were stratified according to age, as indicated by the bar located at the bottom of the monoprint. Each column represents a patient, and each row represents a gene. The column on the right represents the mutation rate of each gene. Different colors denote different types of mutations. f Difference of TMB between patients from the age subgroups. DEG differentially expressed gene; GSEA gene set enrichment analysis; KEGG kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

Enrichment analyses of the DEGs in three datasets

We next performed GO and KEGG enrichment analyses using DEGs from the three datasets. The differential pathways in GO of TCGA-LIHC were as follows: synapse organization, muscle system process, muscle contraction, etc. (Fig. S2a). The differential pathways in GO of GSE14520 were cellular response to xenobiotic stimulus, carboxylic acid biosynthetic process, organic acid biosynthetic process, etc. (Fig. S2b). The differential pathways in GO of GSE140901 were positive regulation of leukocyte migration, T cell activation involved in immune response, leukocyte activation involved in immune response, etc. (Fig. S2c). The results of the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) illustrated that the elderly group was linked to lower expression of oncogenic pathways in KEGG (Fig. 3c–d), such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling pathway in the TCGA-LIHC dataset and Wnt signaling pathway and interleukin (IL)-17 signaling pathway in the GSE1450 dataset. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the differentially downregulated pathway between the two groups on the GSE140901 dataset was the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (Fig. S2d).

Genomic mutation landscape

To explore age-dependent differences in genomic mutations, the information regarding the corresponding somatic alterations in each of the 365 HCC samples was obtained from the TCGA database. The comprehensive landscape of somatic variants revealed the mutation patterns and clinical features of the top 20 genes with the most frequent alterations. TP53, TTN, and CTNNB1 were the top three mutated genes with mutation prevalence rates of 30%, 28%, and 26%, respectively (Fig. 3e). We observed a higher TMB concentration in the elderly group (P = 0.00038, Fig. 3f).

Discussion

In this multicenter retrospective study, patients aged ≥ 65 years with PLC responded better to ICIs than younger patients in terms of DCR and PFS, and similarly to younger patients in terms of ORR and OS, while maintaining a comparable rate of AEs. The differences in genomic characteristics and tumor immune microenvironment may explain the results to some extent.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to report the efficacy and security of ICIs among elderly patients (≥ 65 years) with PLC in real-life condition. Several meta-analyses of clinical trials suggested that ICIs had similar efficacy in older and younger patients [22, 23]. Retrospective studies including various types of cancer (urologic cancer, melanoma, and lung cancer) showed that the long-term clinical outcomes of ICIs were not statistically different between older and younger patients [13, 15, 24]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis including 19 randomized clinical trials clinically demonstrated that patients > 65 years of age benefit more from immunotherapy than younger patients [25]. However, PLC has not been included in those above reports.

In the Keynote-240 phase III trial supporting a favorable risk-to-benefit ratio for pembrolizumab in patients with advanced liver cancer, in the subgroup analysis of patients aged ≥ 65 years, immunotherapy improved PFS compared to placebo, and this was not the case in patients aged < 65 years [26], which was similar to our results. However, it is well known that older patients included in pivotal clinical trials are strictly selected [27]. In contrast to the phase III studies of ICIs [6, 11, 26], our cohort also included patients with more advanced Child-Pugh liver class (B/C) as well as those who received immunotherapy as a third or even fourth line of systemic therapy. Thus, the present cohort more accurately reflects actual treatment in elderly patients with PLC beyond clinical trial programs.

To explore the potential reasons why elderly PLC patients seemed to benefit more from immunotherapy than younger patients, we extracted and analyzed the genomic data. The results showed that DKK1, DLK1, and EPCAM overlapped downregulated DEGs in the elderly group. Previous reports have suggested that overexpression of DKK1 [28], DLK1 [29, 30], and EPCAM [31] acts as unfavorable prognosis predictors in liver cancer. As for the downregulated pathways, the tumor-intrinsic Wnt signaling cascade can affect the immune microenvironment, leading to immune evasion [32]. IL-17A is a tumor-promoting cytokine that critically regulates inflammation and fibrosis [33], and previous research showed that blocking IL-17A may enhance tumor response to immunotherapy [34]. In the TME, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the progression of liver cancer in diverse biological processes like proliferation and metastasis [35], while strongly inhibiting the antitumor immune response [36]. Moreover, the somatic mutation from the TCGA-LIHC dataset showed higher TMB in elderly patients. Existing studies have provided strong evidence that a high TMB might act as a prognostic factor of responsiveness to antitumor immunotherapy [37–39]. Other potential molecular mechanisms in the TME, such as tumor-associated stroma and immune infiltrating cells, could be involved in this age-derived difference in immunotherapy efficacy.

Our study had several limitations. First, owing to the retrospective nature of our analysis, the results should be subsequently validated in prospective clinical trials. Second, although our PLC cohort had a certain number of frail elderly patients, the proportion of elderly patients needs to increase for further study. In addition, the genomic data were obtained from public datasets instead of from our own cohort. The biological measurements of tumor samples were not performed routinely at ICI initiation for most included patients. Future research should focus on exploring the age-dependent changes in intratumoral immune populations and the TME, which may underlie the mechanism of age-mediated difference on the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with PLC.

In conclusion, older patients in real-life setting treated with ICIs had better PFS and DCR and similar OS and ORR compared with younger patients, with no increased AEs. The differences in genomic characteristics and TMB may explain the results to some extent, as the elderly group had some downregulated pathways associated with oncogenicity and immune evasion and had a higher TMB. Our results add to the evidence that ICI should be considered a standard treatment for elderly patients with PLC, to the same degree as for the younger age group that is more represented in landmark trials.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1 Volcano plot of DEGs from GSE140901. DEGs, differentially expressed genes (EPS 1936 KB)

Supplementary Fig. 2 (a-c) GO enrichment analyses of the DEGs identified from TCGA-LIHC (a), GSE14520 (b), and GSE140901 (c). (d) The upregulated and downregulated pathways associated with DEGs of KEGG analysis in GSE140901. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (EPS 10317 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in our study.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: LX and LZ; Resources: HD, LX and LL; Investigation and methodology: HC; Data curation: LZ, HZ, JW, QL, and CH; Formal analysis and visualisation: LZ; Validation: RL, and JH; Writing-original draft: LZ, and HZ; Writing-review and editing: LX and YL; Funding acquisition: LL; Supervision: HZ and LL. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81972897, 82172751), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M701629), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (No. 202201011183), and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022A1515110656).

Data availability

Due to the privacy of patients, the data related to patients cannot be available for public access but can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request approved by the institutional review board of all enrolled centers.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no confict of interest.

Consent to participate

The need for obtaining informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective study design.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study design was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (approval number: NFEC-2021-048).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lushan Xiao, Yanxia Liao, Jiaren Wang, Qimei Li, and Hongbo Zhu have been contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hao Cui, Email: haocui2021@163.com.

Hanzhi Dong, Email: ndzhlyy1394@ncu.edu.cn.

Lin Zeng, Email: lin_zeng1126@163.com.

Li Liu, Email: liuli@i.smu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel A, Martinelli E, Committee EG. Updated treatment recommendations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from the ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulik L, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:477–491.e471. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lian J, Yue Y, Yu W, Zhang Y. Immunosenescence: a key player in cancer development. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:151. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00986-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurez V, Padron AS, Svatek RS, Curiel TJ. Considerations for successful cancer immunotherapy in aged hosts. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;187:53–63. doi: 10.1111/cei.12875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2–3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:977–990. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, Chen Z, Chai X, Xiong J, et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:571–580. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurria A, Levit LA, Dale W, Mohile SG, Muss HB, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Improving the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer: American society of clinical oncology statement. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3826–3833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nemoto Y, Ishihara H, Nakamura K, Tachibana H, Fukuda H, Yoshida K, et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in elderly patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s11255-021-03042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleh K, Auperin A, Martin N, Borcoman E, Torossian N, Iacob M, et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in elderly patients (>/=70 years) with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Eur J Cancer. 2021;157:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossi F, Crinò L, Logroscino A, Canova S, Delmonte A, Melotti B, et al. Use of nivolumab in elderly patients with advanced squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the Italian cohort of an expanded access programme. Eur J Cancer. 2018;100:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perier-Muzet M, Gatt E, Péron J, Falandry C, Amini-Adlé M, Thomas L, et al. Association of immunotherapy with overall survival in elderly patients with melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:82–87. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kugel CH, 3rd, Douglass SM, Webster MR, Kaur A, Liu Q, Yin X, et al. Age correlates with response to anti-PD1, reflecting age-related differences in intratumoral effector and regulatory T-cell populations. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5347–5356. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storm BN, Abedian Kalkhoran H, Wilms EB, Brocken P, Codrington H, Houtsma D, et al. Real-life safety of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in older patients with cancer: an observational study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(7):997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M, et al. International society of geriatric oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–2603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28:1747–1756. doi: 10.1101/gr.239244.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elias R, Giobbie-Hurder A, McCleary NJ, Ott P, Hodi FS, Rahma O. Efficacy of PD-1 & PD-L1 inhibitors in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:26. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poropatich K, Fontanarosa J, Samant S, Sosman JA, Zhang B. Cancer immunotherapies: Are they as effective in the elderly? Drugs Aging. 2017;34:567–581. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbaux P, Maillet D, Boespflug A, Locatelli-Sanchez M, Perier-Muzet M, Duruisseaux M, et al. Older and younger patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors have similar outcomes in real-life setting. Eur J Cancer. 2019;121:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Q, Wang Q, Tang X, Xu R, Zhang L, Chen X, et al. Correlation between patients’ age and cancer immunotherapy efficacy. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1568810. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1568810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, Kudo M, Bouattour M, Lim HY, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenoy P, Harugeri A. Elderly patients’ participation in clinical trials. Perspect Clin Res. 2015;6:184–189. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.167099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R, Zheng C, Wang Q, Bi E, Yang M, Hou J, et al. Identification of an immunogenic DKK1 long peptide for immunotherapy of human multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2021;106:838–846. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.236836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Cui ML, Chen TY, Xie HY, Cui Y, Tu H, et al. Serum DLK1 is a potential prognostic biomarker in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:8399–8404. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittaway JFH, Lipsos C, Mariniello K, Guasti L. The role of delta-like non-canonical Notch ligand 1 (DLK1) in cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021;28:R271–r287. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou L, Zhu Y. The EpCAM overexpression is associated with clinicopathological significance and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;56:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Llovet JM, Castet F, Heikenwalder M, Maini MK, Mazzaferro V, Pinato DJ, et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151–172. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma HY, Yamamoto G, Xu J, Liu X, Karin D, Kim JY, et al. IL-17 signaling in steatotic hepatocytes and macrophages promotes hepatocellular carcinoma in alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2020;72:946–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu C, Liu R, Wang B, Lian J, Yao Y, Sun H et al (2021) Blocking IL-17A enhances tumor response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wu Y, Zhang Y, Qin X, Geng H, Zuo D, Zhao Q. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway-related long non-coding RNAs: roles and mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmacol Res. 2020;160:105195. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Donnell JS, Massi D, Teng MWL, Mandala M. PI3K-AKT-mTOR inhibition in cancer immunotherapy, redux. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;48:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan TA, Yarchoan M, Jaffee E, Swanton C, Quezada SA, Stenzinger A, et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:44–56. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gok Yavuz B, Hasanov E, Lee SS, Mohamed YI, Curran MA, Koay EJ, et al. Current landscape and future directions of biomarkers for immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021;8:1195–1207. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S322289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muhammed A, D'Alessio A, Enica A, Talbot T, Fulgenzi CAM, Nteliopoulos G, et al. Predictive biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2022;22:253–264. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2022.2049244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 Volcano plot of DEGs from GSE140901. DEGs, differentially expressed genes (EPS 1936 KB)

Supplementary Fig. 2 (a-c) GO enrichment analyses of the DEGs identified from TCGA-LIHC (a), GSE14520 (b), and GSE140901 (c). (d) The upregulated and downregulated pathways associated with DEGs of KEGG analysis in GSE140901. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (EPS 10317 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Due to the privacy of patients, the data related to patients cannot be available for public access but can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request approved by the institutional review board of all enrolled centers.