Abstract

Advancements in medicine have enabled the use of monoclonal antibodies in the field of oncology. However, the new adverse effects of immunotherapeutic agents are still being reported. We present the first case of pembrolizumab-induced fatal colitis with concurrent Giardia infection in a patient with metastatic ovarian cancer. A 47-year-old woman with metastatic ovarian cancer who was being treated with pembrolizumab admitted to our clinic complaining of persisting bloody diarrhoea. Her stool antigen test was positive for Giardia. The patient received metronidazole. A colonoscopy with mucosal biopsy was performed upon no clinical or laboratory improvement. Colonoscopy detected deep exudative ulcers in sigmoid colon and rectum. The cytopathological evaluation revealed immune-mediated ischemic colitis. The treatment was rearranged with methylprednisolone. Upon an increase in bloody diarrhoea frequency and C-reactive protein levels, infliximab was started. However, the patient became refractory to infliximab therapy after the second dose and was deceased due to septic shock.

Keywords: Cell-mediated immunity, Colitis, Colonoscopy, Drug side effects, Immunotherapy, Medical oncology

Introduction

The idea that manipulating the immune system to fight malignancy is being applied to some cancer types successfully and it was also awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Allison and Honjo [1]. Although the immunotherapy is a breakthrough in the field of cancer, some rare adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) hinder the application of this therapy [2]. Whereas many adverse effects are manageable, fatal events are also reported. According to a meta-analysis by Wang et al., 613 fatal ICI events were reported from 2009 through January 2018 in World Health Organization (WHO) pharmacovigilance database. 193 of deaths occurred due to anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (ipilimumab or tremelimumab), most were usually from colitis [135 (70%)], whereas anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) (nivolumab, pembrolizumab)/anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab)-related fatalities were usually from pneumonitis [333 (35%)], hepatitis [115 (22%)], and neurotoxic effects [50 (15%)] [3].

Immune checkpoint inhibition with pembrolizumab, which is a humanized monoclonal antibody against PD-1, is one of the effective medications used in progressive ovarian cancer [4]. However, its adverse effects are a major clinical issue for physicians. Immune-mediated colitis is a known adverse effect of pembrolizumab; however, it occurs less than the patients receiving CTLA-4 (ipilimumab and tremelimumab)-based immunotherapy [3]. The current literature reports no pembrolizumab-induced immune-mediated fatal colitis [5]. The aim of this report is to present the first case of pembrolizumab-induced fatal colitis with concurrent Giardia infection in a patient with metastatic ovarian cancer.

Case

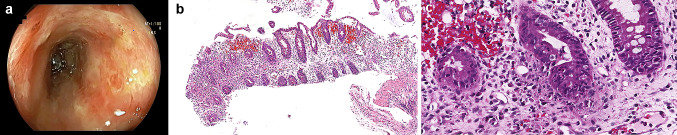

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to our clinic complaining of persisting bloody diarrhoea for 10 days. The patient was diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic ovarian serous adenocarcinoma in July 2019 and underwent cytoreductive surgery. Following the surgery, she had been given her first course of cancer treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Pembrolizumab was added to the patient’s cancer treatment on her second cycle of chemotherapy after the determination of the microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status of the ovarian cancer. After the fourth cycle of the chemotherapy, she received three more cycles only with pembrolizumab. Her last pembrolizumab treatment was 3 weeks prior to the admission. The patient’s physical examination showed decreased skin turgor, pale conjunctiva, and oral mucosal membranes. Laboratory tests on the day of admission were significant for hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, lymphocytopenia, and increased C-reactive protein (CRP) (10.42 mg/dL). Her stool antigen test was negative for Clostridium difficile and Entamoeba histolytica, but positive for Giardia. The patient received metronidazole for the following 10 days in the inpatient setting. Since her CRP levels continued to increase and no clinical improvement was observed in 3 days, a colonoscopy together with mucosal biopsy was performed. Colonoscopy detected deep exudative ulcers in sigmoid colon and rectum (Fig. 1a). Cytopathological evaluation of the biopsy revealed cryptitis and transmucosal necrosis suggesting immune-mediated ischemic colitis (Fig. 1b, c). Pembrolizumab-induced immune-mediated colitis was considered, and the patient’s medical treatment was rearranged as methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Upon an increase in bloody diarrhoea frequency and CRP levels after 3 days of the treatment, infliximab 5 mg/kg was started. The patient’s acute phase reactant levels decreased after the first dose. However, the patient became refractory to infliximab therapy after the second dose and unfortunately, was deceased due to septic shock.

Fig. 1.

a Colonoscopy image of the sigmoid colon showing exudative ulcers. b There is significant active inflammation with extensive crypt loss. They are observed as decreased in size and number, in association with the mucin loss of the crypt epithelia. These findings are consistent with ischemic-like colitis (haematoxylin and eosin). c Prominent neutrophil and eosinophil infiltration and increased apoptosis are observed in the crypt epithelia (haematoxylin and eosin)

Discussion

The Food and Drug Administration approved the use of pembrolizumab for solid cancers with MSI-H status in 2017 [6]. In a review in 2020, administration of immunotherapy in ovarian cancer, albeit not definitive, pointed to encouraging results [7]. Pembrolizumab, which is an anti-PD-1 humanised monoclonal antibody could cause some immune-related adverse effects including pneumonitis, gastritis, and neurotoxic events [5]. The severity of colitis is classified according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Table 1). Pembrolizumab-induced colitis is rare. However, grade 3 and 4 colitis have been reported as an adverse effect in some clinical trials with a mean incidence of 2%. Furthermore, grade 5 colitis, in other words, death due to pembrolizumab-induced colitis, has not been recorded until now [8].

Table 1.

The severity of colitis is classified according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

| Grade | Colitis—clinical presentation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic |

| 2 | Abdominal pain, mucus, blood in stool |

| 3 | Severe pain, fever, peritoneal signs |

| 4 | Life-threatening consequences such as perforation, ischemia, necrosis, bleeding, toxic megacolon |

| 5 | Death |

Immune-mediated colitis requires prompt diagnostic evaluation and true management [9]. In the case of diarrhoea and abdominal pain, infection should be first ruled out. If an infection exists, then the appropriate antibiotic treatment should be given [10]. Another important point in patients with malignancy is the exclusion of the metastasis and metastasis-related complications in the gastrointestinal system, such as perforation or bleeding [11–13].

The gold standard of immune-mediated colitis is colonoscopy and biopsy, including the examination of the ileum. In addition, the biopsy should be evaluated by an experienced pathologist since it could be difficult to distinguish from the inflammatory bowel diseases [14]. The management of immune-mediated colitis mainly consists of immunosuppressive agents according to the severity of the colitis [9]. In cases such as the presented one, meaning grade 3 or more severe colitis, the immune checkpoint inhibitor drug should be stopped, and systemic corticosteroids should be initiated. One-third to two-thirds of patients could be refractory to steroid treatment [15]. Then, the second-line treatment infliximab is initiated and mainly successful [16]. If the patient does not improve, the next step is vedolizumab, which is an antibody against the 0.4ß7-integrin on the surface of CD4 + T cells. The usage of vedolizumab is written in a few clinical reports, but there are no clear treatment algorithms for this therapy [17, 18].

Anti-PD-1 antibodies mostly cause immune-related adverse events (irAEs) occur within the first 6 months of the treatment and fatal outcomes occur more frequently and earlier if the patients receive ICI combination therapy [19]. Due to the growing use of ICIs in oncology, clinicians are facing with irAEs; thus, awareness of this complications needs to be raised regarding the clinical presentation, early diagnosis and appropriate management of these toxicities, to have a better survival rate in cancer patients [20].

Conclusion

Although the Giardia infection was treated and the severity of immune-mediated colitis tried to be reduced with proven strategy: first, corticosteroid and then infliximab, the patient became refractory to these treatments and was deceased before the third-line medication (vedolizumab) could be administered. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of pembrolizumab-induced colitis with concurrent giardia infection, resulting in death despite the appropriate treatment. This case demonstrated that immune-mediated colitis could be very severe, even fatal, and further research is needed for better treatment options for this clinical situation.

Funding

The authors did not receive any type of support from any institutions or persons.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in the submitted article are the authors’ and not an official position’s of the institution or funder’s.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nobel Prize Organisation (2018) The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2018. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2018/press-release. Accessed 18 November 2020

- 2.Wang Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Mao E, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea and colitis in patients with advanced malignancies: retrospective review at MD Anderson. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:37. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Som A, Mandaliya R, Alsaadi D, Farshidpour M, Charabaty A, Malhotra N, Mattar MC. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: a comprehensive review. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:405–418. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borella F, Ghisoni E, Giannone G, Cosma S, Benedetto C, Valabrega G, Katsaros D. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in epithelial ovarian cancer: an overview on efficacy and future perspectives. Diagnostics. 2020;10:146. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10030146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1721–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration (2017) FDA approves first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with a specific genetic feature. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-cancer-treatment-any-solid-tumor-specific-genetic-feature. Accessed 18 November 2020

- 7.Palaia I, Tomao F, Sassu CM, Musacchio L, Benedetti Panici P. Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer: recent advances and combination therapeutic approaches. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:6109–6129. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S205950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC, Schindler K, Lacouture ME, Postow MA, Wolchok JD. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linardou H, Gogas H. Toxicity management of immunotherapy for patients with metastatic melanoma. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:272. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.07.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A, De Felice KM, Loftus EV, Jr, Khanna S. Systematic review: colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:406–417. doi: 10.1111/apt.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dilling P, Walczak J, Pikiel P, Kruszewski WJ. Multiple colon perforation as a fatal complication during treatment of metastatic melanoma with ipilimumab—case report. Pol Przegl Chir. 2014;86:94–96. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2014-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burdine L, Lai K. Laryea JA (2014) Ipilimumab-induced colonic perforation. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;3:rju010. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rju010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah R, Witt D, Asif T, Mir FF. Ipilimumab as a Cause of Severe Pan-colitis and colonic perforation. Cureus. 2017;9:e1182. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol. 2006;15:2283–2289. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marthey L, Mateus C, Mussini C, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies induces an inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:395–401. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston RL, Lutzky J, Chodhry A, Barkin JS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody-induced colitis and its management with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2538–2540. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergqvist V, Hertervig E, Gedeon P, et al. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:581–592. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1962-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh AH, Ferman M, Brown MP, Andrews JM. Vedolizumab: a novel treatment for ipilimumab-induced colitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016216641. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelao L, Criscitiello C, Esposito A, Goldhirsch A, Curigliano G. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer treatment: a double-edged sword cross-targeting the host as an "innocent bystander". Toxins (Basel) 2014;6:914–933. doi: 10.3390/toxins6030914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:563–580. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]