Abstract

Background

Cancer cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by weight loss leading to immune dysfunction that is commonly observed in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We examined the impact of cachexia on the prognosis of patients with advanced NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab and evaluated whether the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia affects the clinical outcome.

Patients and methods

Consecutive patients with advanced NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab were retrospectively enrolled in the study. Serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and appetite-related hormones, which are related to the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia, were analyzed. Cancer cachexia was defined as (1) a body weight loss > 5% over the past 6 months, or (2) a body weight loss > 2% in patients with a body mass index < 20 kg/m2.

Results

A total of 133 patients were enrolled. Patients with cachexia accounted for 35.3%. No significant difference in the objective response rate was seen between the cachexia and non-cachexia group (29.8% vs. 34.9%, P = 0.550), but the median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) periods were significantly shorter in the cachexia group than in the non-cachexia group (PFS: 4.2 months vs. 7.1 months, P = 0.04, and OS: 10.0 months vs. 26.6 months, P = 0.03). The serum TNF-alpha, IL-1 alpha, IL-8, IL-10, and leptin levels were significantly associated with the presence of cachexia, but not with the PFS or OS.

Conclusion

The presence of cachexia was significantly associated with poor prognosis in advanced NSCLC patients receiving pembrolizumab, not with the response to pembrolizumab.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-021-02997-2.

Keywords: Cancer cachexia, Non-small cell lung cancer, Pembrolizumab, Pro-inflammatory cytokine, Ghrelin, Leptin

Introduction

Cancer cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by weight loss and caused by a variable combination of systemic inflammation, hyper catabolism, and anorexia [1–3]. It is observed in approximately half of patients with advanced cancer and leads to approximately 20% of deaths [3–5]. Cancer cachexia progresses to irreversible malnutrition as cancer progresses, involving endocrine factors and a variety of mediators including inflammatory and immune cells [4]. Reportedly, poor nutrition and weight loss, the hallmarks of cancer cachexia, also affect systemic immunity negatively [6, 7].

PD-(L)1 inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and nivolumab have become standard treatments either as monotherapies or in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [8–12], and these inhibitors have produced durable responses in responders [13, 14]. In general, the prevalence of cancer cachexia is higher among patients with advanced lung cancer, compared with patients with other types of solid tumors [15–17]. From this perspective, it would be worthwhile to investigate the impact of the clinical outcomes of PD-1 inhibitor in advanced NSCLC patients with cachexia. Several studies have shown poor prognosis in advanced NSCLC patients with cachexia who received PD-1 inhibitor [18, 19]. However, these reports did not show an association between clinical outcomes and the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia, which is a multifactorial condition consisting of systemic inflammation and metabolic changes.

In the present study, we examined the impact of cachexia on the prognosis of patients with advanced NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab and evaluated whether the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia affects the clinical outcome.

Materials and methods

Patients

We retrospectively accrued consecutive patients with advanced NSCLC who had been treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy at the National Cancer Center Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) between March 2017 and December 2018. Patients whose weight loss could not be accurately assessed were excluded. Data for pre-treatment patient characteristics, including age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), smoking history, body mass index (BMI), and body weight change during the previous 6 months, were collected. The levels of albumin (ALB), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were also measured in routine examinations performed before pembrolizumab administration.

Tumor characteristics, including histology, tumor molecular profiling for EGFR mutation and ALK fusion, PD-L1 status, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification as proposed by the 8th edition of Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), and number of metastatic organs, were noted. Data on the treatment characteristics including the chemotherapy regimen, and the number of the treatment line, efficacy, progression-free survival (PFS), duration of response (DOR), and overall survival (OS) were also collected.

Definition of cancer cachexia

In this study, we defined the presence of cachexia as meeting either (1) an involuntary weight loss of > 5% over the past 6 months, or (2) body mass index (BMI) < 20 kg/m2 and any degree of weight loss > 2%, based on an international consensus published in 2011 [3].

Analysis of PD-L1 expression

The expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells was assessed using the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharm Dx assay (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The percentages of membranous PD-L1-positive tumor cells were evaluated for each sample [20].

Measurement of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and appetite-related hormones

The serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1 alpha, IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-alpha) and appetite-related hormones (ghrelin and leptin), which are related to the pathogenesis of cancer cachexia, were measured using a magnetic bead-based assay. The MILLIPLEX® MAP human Metabolic Hormone Magnetic Bead Panel Kit and the MILLIPLEX® MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel Kit were obtained from Merck Millipore Corporation (Massachusetts USA). The multiplex assay was conducted using the Luminex® 100/200TM System (Luminex Corp., Texas USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were generated using the specific standards supplied by the manufacturer. The data were analyzed using MILLIPLEX® Analyst 5.1 software (Merck Millipore Corp.).

Survival analysis

Tumor responses were classified according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST), version 1.1 [21]. The PFS was calculated from the date of the initiation of pembrolizumab treatment until the detection of the earliest signs of disease progression using computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or patient death. The DOR was calculated as the date of the initiation of pembrolizumab treatment until the disease progression or patient death in patient who had the best response of complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). The OS was calculated from the date of the initiation of pembrolizumab treatment until the date of death. The cutoff date was January 1, 2020.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the patient characteristics between the cachexia and non-cachexia groups were analyzed using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. The PFS, DOR, and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival between the two groups. Sex, age, PS, histology, driver mutation smoking status, PD-L1 status, number of metastatic organs, and cachexia were included as covariates in the multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazard model). The cytokine and hormone levels were compared between the two groups using an unpaired t test. Differences with probability values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA SE version 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and GraphPad Prism version 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software, California, USA). This study was approved by an institutional review board (2015-355).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 157 patients with advanced NSCLC who received pembrolizumab were identified between March 2017 and December 2018. A total of 24 patients were excluded; 23 patients lacked information regarding body weight, and one patient was unable to consume food because of the presence of gastrointestinal obstruction disorder. Finally, 133 patients were analyzed in this study. Patients with cachexia accounted for 35.8% (47 out of 133) of this cohort (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics for the 133 patients are shown in Table 1. Seventy-eight patients (58.6%) received pembrolizumab as a first-line therapy. No difference in the PD-L1 expression level was seen between the cachexia and the non-cachexia groups. Compared with the non-cachexia group, the cachexia group contained more smokers (P = 0.048), exhibited stronger inflammatory findings (CRP and NLR), and had a significantly lower ALB (P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics (N = 133)

| Cachexia | Non-cachexia | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 47 (35) | 86 (65) | |

| Age, median (range) | 63 (33–86) | 65 (33–85) | 0.750 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 34 (72) | 54 (74) | |

| Female | 13 (28) | 32 (26) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0–1 | 39 (83) | 75 (87) | 0.505 |

| 2–3 | 8 (17) | 11 (13) | |

| Stage | |||

| Recurrence | 8 (17) | 24 (28) | – |

| III | 8 (17) | 15 (17) | |

| IV | 31 (66) | 47 (55) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 4 (9) | 19 (22) | 0.048 |

| Current or former | 43 (91) | 67 (78) | |

| Histology | |||

| Non-Sq | 39 (83) | 74 (86) | 0.636 |

| Sq | 8 (17) | 12 (14) | |

| Driver gene* | |||

| Yes | 5 (11) | 8 (10) | 0.804 |

| No | 42 (89) | 78 (90) | |

| PD-L1 expression, % | |||

| ≥ 50 | 39 (83) | 67 (78) | 0.487 |

| 1–49 | 8 (17) | 19 (22) | |

| Prior lines of therapy | |||

| 0 | 31 (66) | 47 (55) | 0.206 |

| ≥ 1 | 16 (34) | 39 (45) | |

| No. of metastatic organs | |||

| < 3 | 9 (19) | 21 (24) | 0.478 |

| ≥ 3 | 38 (81) | 65 (76) | |

| ALB, g/dL | |||

| < 3.5 | 30 (64) | 24 (28) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3.5 | 17 (36) | 62 (72) | |

| CRP, mg/dL | |||

| < 1 | 13 (28) | 51 (59) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 1 | 34 (72) | 35 (41) | |

| NLR | |||

| < 5 | 19 (40) | 63 (73) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 5 | 28 (60) | 23 (27) | |

ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score, Sq squamous cell carcinoma, PD-L1 programmed death-ligand-1, ALB albumin, CRP C-reactive protein, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

Driver gene* indicates the results of testing for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene fusion

P values were calculated by comparing the cachexia and non-cachexia groups

Impact of cachexia on clinical outcomes of pembrolizumab

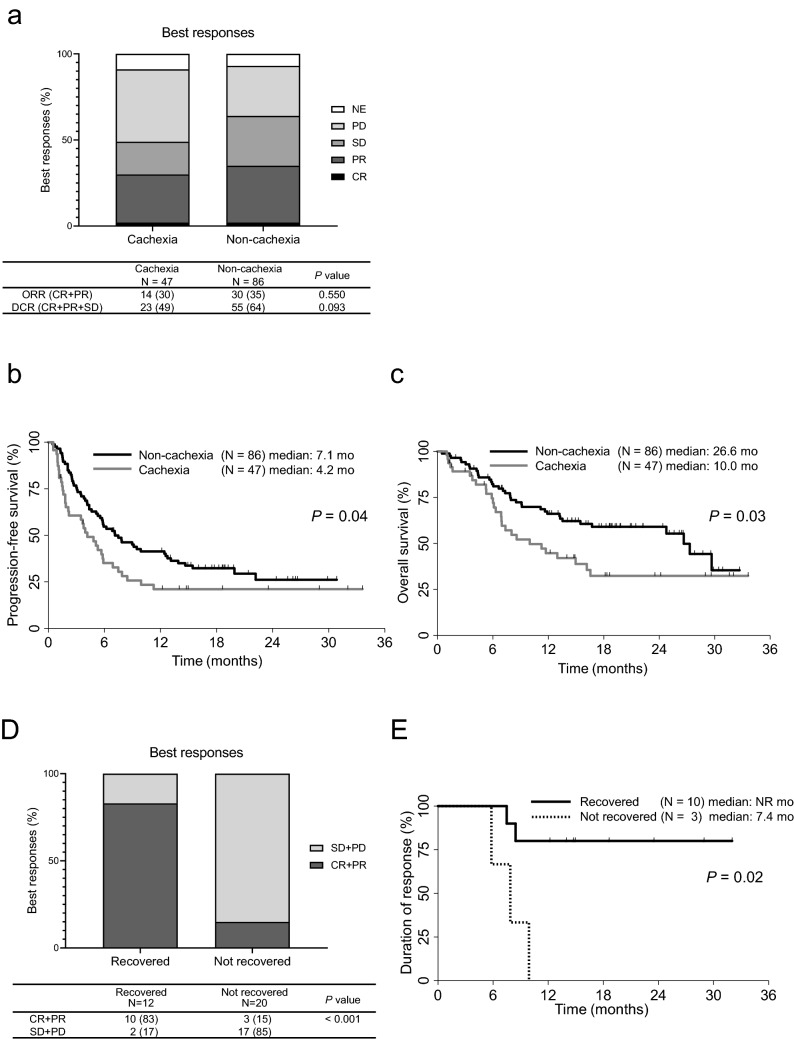

The objective response rate (ORR) for patients receiving pembrolizumab was 29.8% in the cachexia group and 34.9% in the non-cachexia group. No significant differences in ORR (P = 0.550) or the disease control rate (P = 0.093) were seen between the two groups (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, the median PFS in the cachexia group was significantly shorter than that in non-cachexia group (4.2 months [95% CI, 1.9–5.9 months] vs. 7.1 months [95% CI, 5.3–12.5 months]; HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.42–0.97; P = 0.04; Fig. 2b). The median OS in the cachexia group was also significantly shorter than that in the non-cachexia group (10.0 months [95% CI, 6.9–16.6 months] vs. 26.6 months [95% CI, 15.5–NR months]; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34–0.93; P = 0.03; Fig. 2c). A multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model showed that non-cachexia (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.02–2.46; P = 0.04) and a higher PD-L1 status (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.48–0.79; P = 0.004) contributed significantly to a longer PFS. A similar analysis was conducted for OS and showed that non-cachexia (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.03–2.95; P = 0.04), a higher PD-L1 (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.23–0.75; P = 0.003), and a better PS (HR, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.04–4.47; P = 0.04) were also associated with longer survival (Table 2). Details of the subsequent therapies that were used are shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Thirty-eight percent of patients with cachexia (18 of 47 patients) and 48% of patients with non-cachexia (41 of 86 patients) received subsequent treatments. No significant difference in the proportion of patients receiving subsequent treatment after pembrolizumab was seen between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

a Objective responses, b progression-free survival and c overall survival for patients treated with pembrolizumab in the cachexia (N = 47) and the non-cachexia (N = 86) groups. d Best responses (PR or CR and SD or PD) in the body weight recovered (N = 12) and the not recovered (N = 20) groups. e Duration of response in the body weight recovered (N = 10) and not recovered (N = 3) groups among patients with CR or PR. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; NR, not reached. P value was calculated by comparing the recovered and the not recovered groups

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with PFS and OS (N = 133)

| Covariates | PFS | OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | P value | HR [95% CI] | P value | ||

| Cachexia | No. versus Yes | 1.58 [1.022 − 2.464] | 0.040 | 1.74 [1.027 − 2.947] | 0.039 |

| Age, in years | < 74 versus ≥ 75 | 0.69 [0.352 − 1.359] | 0.285 | 1.01 [0.466 − 2.189] | 0.979 |

| Sex | Female versus Male | 1.02 [0.615 − 1.696] | 0.934 | 1.13 [0.611 − 2.089] | 0.696 |

| ECOG PS | 0–1 versus 2–3 | 1.24 [0.652 − 2.373] | 0.508 | 2.15 [1.042 − 4.467] | 0.038 |

| Histology | Sq versus Non-Sq | 1.02 [0.552 − 1.894] | 0.943 | 1.24 [0.541 − 2.823] | 0.616 |

| Driver gene* | No. versus Yes | 2.01 [0.996 − 4.061] | 0.051 | 1.20 [0.523 − 2.751] | 0.667 |

| Smoking history | Never versus Ever | 0.61 [0.329 − 1.154] | 0.601 | 0.65 [0.296 − 1.434] | 0.287 |

| PD-L1 status, in % | 1–49 versus ≥ 50 | 0.48 [0.293 − 0.794] | 0.004 | 0.42 [0.233 − 0.748] | 0.003 |

| No. of metastasis organs | < 3 versus ≥ 3 | 1.74 [0.983 − 3.088] | 0.057 | 1.59 [0.793 − 3.180] | 0.191 |

PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score, Sq squamous cell carcinoma, PD-L1 programmed death-ligand-1, ALB albumin, CRP C-reactive protein, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

Driver gene* indicates the results of testing for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene fusion

Changes in body weight during pembrolizumab treatment

Next, we examined the change in body weight during pembrolizumab treatment in 32 of the 47 patients with cachexia whose body weights after the initiation of pembrolizumab treatment were available. Among 12 patients who recovered from body weight loss, 10 (83%) achieved a CR or PR, and all had a PD-L1 expression TPS of over 90%. In contrast, only 3 (15%) of the 20 patients who did not recover their body weight achieved tumor response (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2d). Moreover, the DOR in the patients who achieved CR or PR and recovered from cachexia was significantly longer than that in patients who achieved CR or PR but did not recover their body weight (HR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.019–0.726; P = 0.02; Fig. 2e).

Correlations of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines and appetite-related hormone levels with cachexia

Pre-treatment serum samples were available in 116 patients (85.7%). Of these, patients with cachexia accounted for 34.5% (40 out of 116). We measured the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines related to the pathogenesis of cachexia. Inflammatory cytokine levels, namely TNF-alpha (P = 0.046), IL-1 alpha (P = 0.043), IL-8 (P = 0.016), and IL-10 (P = 0.019), were significantly higher in the cachexia group (Fig. 3). On the other hand, these cytokine levels were not associated with the prognosis (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of serum pro-inflammatory cytokine and appetite-related hormone levels with cachexia (N = 116). TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL, interleukin. P values were calculated by comparing the cachexia and the non-cachexia groups

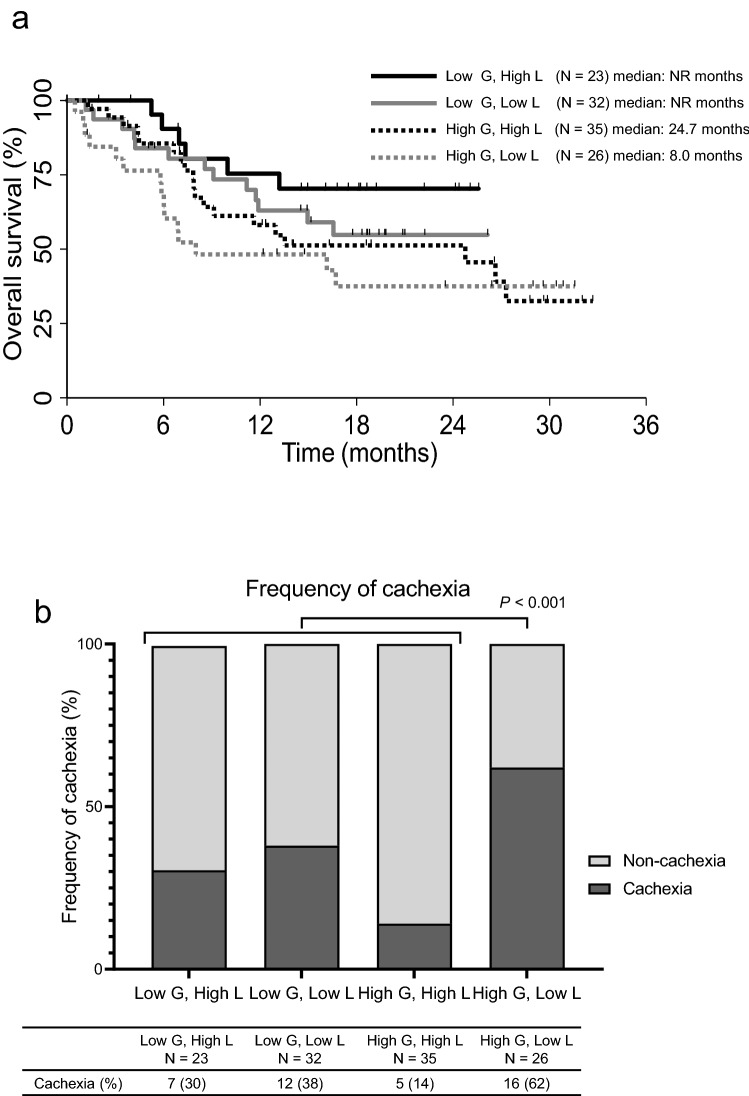

Next, we also measured the levels of the appetite-related hormones ghrelin and leptin. The leptin level was significantly lower in the cachexia group (P = 0.002), while no significant difference in the ghrelin level was seen between the two groups (P = 0.425) (Fig. 3). We performed an exploratory analysis of the survival curves for four groups of patients divided according to the levels of ghrelin and leptin (low ghrelin and high leptin, low ghrelin and low leptin, high ghrelin and high leptin, high ghrelin and low leptin) (Fig. 4a). The high ghrelin and low leptin group had the shortest survival period among the four groups. Furthermore, 62% of the patients in the high ghrelin and low leptin group had cachexia, and this group had a higher percentage of patients with cachexia than the other groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Analyses of patient survival and frequency of cachexia according to ghrelin and leptin levels. a Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival for four groups by classified according to ghrelin and leptin levels. b Proportion of patients with cachexia in the four groups classified according to ghrelin and leptin levels. Low G, low ghrelin level; low L, low leptin level; high G, high ghrelin level; high L, high leptin level. *P values were calculated by comparing the high G, low L group with the rest

Discussion

The present study investigated the impact of cachexia on the clinical outcomes of 133 patients with advanced NSCLC who were treated with pembrolizumab. Our study demonstrated that patients with cachexia who were treated with pembrolizumab had a relatively poor prognosis. In a multivariate analysis, the presence of cachexia was associated with shorter PFS and OS periods in patients treated with pembrolizumab. Furthermore, we evaluated the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and appetite-related hormones related to cachexia. Patients with cachexia had higher inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-alpha, IL-1 alpha, IL-8, and IL-10) and higher leptin levels, but the levels of these markers were not associated with prognosis. The present results clearly demonstrate that cachexia as a clinical feature, defined as an involuntary weight loss of 5% or more in the past 6 months or a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2 and a weight loss of 2% or more, is associated with poor prognosis of patients receiving pembrolizumab.

In cancer cachexia, inflammatory mediators such as TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-1, and IL-6 are released, causing decrease in appetite and increases in energy expenditure and muscle atrophy [2]. These factors promote the expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus and suppress ghrelin, resulting in a further loss of appetite [22]. Additionally, inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 are transmitted to the hypothalamus as leptin-like signals, leading to inappropriate appetite suppression. IL-8 secretion is reportedly associated with the depletion of adipose tissue in vitro [23], and higher IL-8 levels promote the growth of cancer cells, and have been linked to angiogenesis, metastatic spread, and poor prognosis [24–26]. Schalper et al. and Yuen et al. found that the IL-8 serum level was correlated with poor prognosis in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [27, 28]. In addition, Laino et al. reported that higher levels of IL-6 were prognostic factor associated with shorter overall survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving ICIs or chemotherapy in large randomized trials [29]. In the present study, the serum CRP, NLR, TNF-α, IL-1, IL-8, and IL-10 levels were significantly elevated in the cachexia group. IL-6 level was also higher in the cachexia group than in the non-cachexia group, although the difference was not significant. These results suggest that cachexia patients are in a state of higher inflammatory activity and hyper-metabolism, consistent with the findings of previous reports [17, 30].

We also focused on the appetite-related hormones ghrelin and leptin. Ghrelin is an endogenous ligand of the growth hormone (GH) secretagogue receptor 1a and stimulates multiple pathways that regulate appetite, lean body mass, body weight, and metabolism [31, 32]. Ghrelin is secreted in response to fasting and activates the appetite promotion pathway [33]. As cancer cachexia progresses, ghrelin levels increase because of ghrelin resistance [17]. Leptin, on the other hand, decreases secretion with fasting and promotes increased appetite. Leptin is a hormone whose release is partly regulated by the amount of adipose tissue; a decrease in adipose mass, such as in cachexia, results in decrease in leptin secretion [34, 35]. Therefore, as cachexia progresses, ghrelin secretion progressively increases and leptin secretion progressively decreases.

In the present study, the leptin level was significantly lower in the cachexia group, while no significant difference in ghrelin levels was seen between the two groups. Additionally, higher proportion of cachexia patients was observed in the high ghrelin and low leptin group than in the other groups (P < 0.001). The median OS in the high ghrelin and low leptin group was also the shortest among the four different groups. These results suggest that in terms of the process of cachexia progression, the high ghrelin and low leptin group with the relatively poor prognosis may represent the most advanced stage of cachexia, known as “refractory cachexia.”

Anamorelin (ONO-7643), a novel selective ghrelin receptor agonist, has recently been developed for the treatment of patients with NSCLC and cachexia. Anamorelin significantly increased the lean body mass and improved anorexia symptoms and the nutritional status [36, 37]. On the other hand, biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of anamorelin have not yet been established. Anamorelin could be a beneficial treatment option for “non-refractory cachexia” patients with low ghrelin levels, rather than for patients with severe cachexia who have become resistant to ghrelin.

The present study examining advanced NSCLC patients receiving pembrolizumab showed no difference in the ORR between the cachexia and non-cachexia groups, but the PFS and OS were significantly shorter in the patients with cachexia. First, the reason for this difference could be the presence of higher inflammatory findings, such as CRP level and NLR, in the cachexia patients. In general, CRP level and NLR are prognostic factors for multiple types of cancer [38–42]. Additionally, CRP level and NLR are known to be prognostic factors (with higher levels associated with shorter overall survival) in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving ICIs or chemotherapy [43–45]. Recent data have also shown that CRP binds to the T-cells of patients with melanoma and suppresses their function in a dose-dependent manner at the earliest stage of T-cell activation [44, 46]. Indeed, CRP level and NLR were significantly associated with the patient outcome in the present study (Supplemental Figure 1a, b). Another reason could be the irreversible progression of cancer cachexia. In general, cancer cachexia is characterized by progressive and irreversible weight loss, but some of the patients in the present series succeeded in gaining weight after treatment with pembrolizumab. Among those patients, 83% responded to pembrolizumab (CR or PR) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, some patients achieved CR or PR but did not recover their body weight loss. The DOR in these patients who achieved CR or PR was significantly shorter than that in patients who regained their body weight (HR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.019–0.726; P = 0.02) (Fig. 3b). These results suggested that patients with irreversible cachexia were unable to attain a stable response, even if PD-1 inhibitor successfully produced the response. Future evaluations of how cachexia affects immunity in cachexia patients are needed.

The present study had several limitations. First, this study was a single-center, retrospective analysis involving a small sample size. Second, although we used Fearon’s [3] definition of cachexia, which has been internationally adopted for diagnosis of cachexia, the present study did not include any data regarding sarcopenia. Thus, the number of cachexia patients might have been underestimated in our cohort. Third, we focused on only patients treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy. Factors other than cachexia, such as an elderly age, a poor PS, and PD-L1 expression, can affect efficacy in patients treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy, compared with those treated with chemotherapy plus immunotherapy. Therefore, we examined PFS and OS using multivariate analyses that included these factors. The presence of cachexia was significantly associated with a poor outcome among patients treated with pembrolizumab.

Conclusion

The present study showed that patients with cachexia who were treated with pembrolizumab had relatively poor prognosis, whereas some of those who responded to PD-1 inhibitor were able to recover from cachexia. Moreover, we also found that when cachexia was classified according to the ghrelin and leptin levels, the data supported distinguishable stages of cachexia. Further studies are needed to clarify the complex biology of cancer cachexia and to evaluate the clinical relevance of these cachexia-related markers.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental Figure 1. Overall survival according to CRP level and NLR (N = 133). Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival according to (a) CRP level and (b) NLR. CRP, C-reactive protein; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NR, not reached. (PDF 102 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank Shoko Azuhata for her donation to the study and all the patients who contributed to this study. We also thank all the investigators from the oncologic department of the National Cancer Center Hospital, for their participation and contributions.

Abbreviations

- ALB

Albumin

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CR

Complete response

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- DOR

Duration of response

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- GH

Growth hormone

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IL-1

Interleukin-1

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-(L)1

Programmed cell death (ligand) 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- PS

Performance status

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- TNF-alpha

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TNM

Tumor-node-metastasis

- UICC

Union for International Cancer Control

Author’s contribution

HJ, TY, HH, and SY designed the study, performed data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. HJ, TY, HH, SY, YM, YS, YO, YG, NY, KT, MN, and YO read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Nothing.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request. De-identified datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration

Conflict of interest

HJ has nothing to disclose. TY reports grants from ONO Pharmaceutical, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, grants from Takeda, personal fees from Chugai, personal fees from Novartis, grants from MSD, grants from AbbVie, outside the submitted work; HH reports grants and personal fees from BMS, grants and personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Chugai, grants and personal fees from Taiho, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Astellas, grants from Merck Serono, grants from Genomic Health, grants and personal fees from Lilly, grants and personal fees from Ono, outside the submitted work; SY has grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim. YM reports grants from National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund, grants from Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, grants from Hitachi, Ltd., grants from Hitachi High-Technologies, personal fees from Olympus, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from COOK, personal fees from AMCO INC., outside the submitted work; YS has nothing to disclose. YO reports personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K., personal fees from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Eli Lilly K.K., personal fees from MSD K.K., personal fees from Chugai Pharma Co., Ltd, personal fees from Ono Pharma Co., Ltd, personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work; YG reports grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, grants and personal fees from Chugai, grants and personal fees from Taiho Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Guardant Health, grants and personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, grants from Kyorin, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Illumina, outside the submitted work; NY reports grants from Chugai, grants from Taiho, grants from Eisai, grants from Lilly, grants from Quintiles, grants from Astellas, grants from BMS, grants from Novartis, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Pfizer, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, grants from Bayer, grants from ONO PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD, grants from Takeda, personal fees from ONO PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD, personal fees from Chugai, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from BMS, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Cimic, grants from Janssen Pharma, grants from MSD, grants from Merck, personal fees from Sysmex, grants from GSK, grants from Sumitomo Dainippon, outside the submitted work; KT reports grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., grants and personal fees from Nippon Boehringer lngelheim Co., Ltd., grants and personal fees from MSD K.K, grants from Glaxo SmithKline Consumer Healthcare Japan K.K, grants from NIPPON SHINYAKU CO., LTD., grants from TSUMURA & CO., grants and personal fees from Pfizer Inc., personal fees from AstraZeneca K.K, grants and personal fees from TAIHO PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD., grants from DAIICHI SANKYO Co., LTD., grants from Astellas Pharma Inc., grants and personal fees from KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., grants from KYOWA Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., grants from TEIJIN PHARMA LIMITED, grants from Sanofi K.K., grants and personal fees from ONO PHARMACEUTICAL CO., LTD., grants from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb Company, grants and personal fees from Novartis Pharma K.K, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K, grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Japan Ltd., grants from NIPRO PHARMA CORPORATION, grants from Astellas Pharma lnc., grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited., grants from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, grants from Torii Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, personal fees from MSD K.K, personal fees from Meiji Seika Pharma Co, Ltd., outside the submitted work; NM reports grants and personal fees from Ono, personal fees from BMS, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Taiho, personal fees from Chugai, personal fees from Miraca Life Science, personal fees from Beckton Dickinson Japan, personal fees from Covidien Japan Inc, outside the submitted work; YO reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Chugai, personal fees from Celltrion, personal fees from Amgen, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, from Janssen, grants and personal fees from Kyorin, grants and personal fees from Nippon Kayaku, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from ONO Pharmaceutical, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants from Ignyta, grants and personal fees from Taiho, grants and personal fees from Takeda, outside the submitted work.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

This study was approved by an institutional review board (2015–355).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aoyagi T, Terracina KP, Raza A, et al. Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(4):17–29. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i4.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argiles JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B, et al. Cancer cachexia: understanding the molecular basis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(11):754–762. doi: 10.1038/nrc3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):489–495. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon KC, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell Metab. 2012;16(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baracos VE, Martin L, Korc M, et al. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:17105. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flint TR, Fearon DT, Janowitz T. Connecting the metabolic and immune responses to cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(5):451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keusch GT, Farthing MJ. Nutrition and infection. Annu Rev Nutr. 1986;6:131–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonia SJ, Borghaei H, Ramalingam SS, et al. Four-year survival with nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1395–1408. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30407-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(28):2518–2527. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baracos VE, Reiman T, Mourtzakis M, et al. Body composition in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a contemporary view of cancer cachexia with the use of computed tomography image analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1133S–S1137. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantovani G, Maccio A, Madeddu C, et al. Randomized phase III clinical trial of five different arms of treatment in 332 patients with cancer cachexia. Oncologist. 2010;15(2):200–211. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Asakawa A, Amitani H, et al. Cancer cachexia–pathophysiology and management. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(5):574–594. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0787-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyawaki T, Naito T, Kodama A, et al. Desensitizing effect of cancer cachexia on immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2020.100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roch B, Coffy A, Jean-Baptiste S, et al. Cachexia—sarcopenia as a determinant of disease control rate and survival in non-small lung cancer patients receiving immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2020;143:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roach C, Zhang N, Corigliano E, et al. Development of a companion diagnostic Pd-L1 immunohistochemistry assay for pembrolizumab therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24(6):392–397. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujitsuka N, Asakawa A, Uezono Y, et al. Potentiation of ghrelin signaling attenuates cancer anorexia-cachexia and prolongs survival. Transl Psychiatry. 2011;1:e23. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerhardt CC, Romero IA, Cancello R, et al. Chemokines control fat accumulation and leptin secretion by cultured human adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;175(1–2):81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acosta JC, O'Loghlen A, Banito A, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133(6):1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Rodríguez-Ruiz ME, et al. Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment and follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;60:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan A, Chen JJ, Yao PL, et al. The role of interleukin-8 in cancer cells and microenvironment interaction. Front Biosci. 2005;10:853–865. doi: 10.2741/1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schalper KA, Carleton M, Zhou M, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-8 is associated with enhanced intratumor neutrophils and reduced clinical benefit of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):688–692. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuen KC, Liu LF, Gupta V, et al. High systemic and tumor-associated IL-8 correlates with reduced clinical benefit of PD-L1 blockade. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0860-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laino AS, Woods D, Vassallo M, et al. Serum interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein are associated with survival in melanoma patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson G, Salle A, Lorimier G, et al. Cancer cachexia: measured and predicted resting energy expenditures for nutritional needs evaluation. Nutrition. 2008;24(5):443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundholm K, Gunnebo L, Korner U, et al. Effects by daily long term provision of ghrelin to unselected weight-losing cancer patients: a randomized double-blind study. Cancer. 2010;116(8):2044–2052. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschop M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407(6806):908–913. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davenport AP, Bonner TI, Foord SM, et al. International union of pharmacology. LVI. Ghrelin receptor nomenclature, distribution, and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(4):541–6. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora GK, Gupta A, Narayanan S, et al. Cachexia-associated adipose loss induced by tumor-secreted leukemia inhibitory factor is counterbalanced by decreased leptin. JCI Insight. 2018 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395(6704):763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katakami N, Uchino J, Yokoyama T, et al. Anamorelin (ONO-7643) for the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and cachexia: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of Japanese patients (ONO-7643-04) Cancer. 2018;124(3):606–616. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temel JS, Abernethy AP, Currow DC, et al. Anamorelin in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and cachexia (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2): results from two randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, et al. An inflammation-based prognostic score (mGPS) predicts cancer survival independent of tumour site: a Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(4):726–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pastorino U, Morelli D, Leuzzi G, et al. Baseline and postoperative C-reactive protein levels predict mortality in operable lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang S, Wang Y, Sui D, et al. C-reactive protein as a marker of melanoma progression. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(12):1389–1396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMillan DC. An inflammation-based prognostic score and its role in the nutrition-based management of patients with cancer. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(3):257–262. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108007131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agnoli C, Grioni S, Pala V, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation and breast cancer risk: a case-control study nested in the EPIC-Varese cohort. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartlett EK, Flynn JR, Panageas KS, et al. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with treatment failure and death in patients who have melanoma treated with PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy. Cancer. 2019;126(1):76–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida T, Ichikawa J, Giuroiu I, et al. C reactive protein impairs adaptive immunity in immune cells of patients with melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Capone M, Giannarelli D, Mallardo D, et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and derived NLR could predict overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0383-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang L, Liu SH, Wright TT, et al. C-reactive protein directly suppresses Th1 cell differentiation and alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2015;194(11):5243–5252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Overall survival according to CRP level and NLR (N = 133). Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival according to (a) CRP level and (b) NLR. CRP, C-reactive protein; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NR, not reached. (PDF 102 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. De-identified datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.