Abstract

Background

Antigen-presenting cells (APC)/T/NK cells are key immune cells that play crucial roles in fighting against malignancies including lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). In this study, we aimed to identify an APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature (ATNKGS) and potential immune cell-related genes (IRGs) to realize risk stratification, prognosis, and immunotherapeutic response prediction for LUAD patients.

Methods

Based on the univariate Cox regression and the LASSO Cox regression results of 196 APC/T/NK cells-related genes collected from three pathways in the KEGG database, we determined the final genes and established the ATNKGS-related risk model. The single-cell RNA sequencing data were applied for key IRGs identification and investigate their value in immunotherapeutic response prediction. Several GEO datasets and an external immunotherapy cohort from Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, were applied for validation.

Results

In this study, nine independent public datasets including 1108 patients were enrolled. An ATNKGS containing 16 genes for predicting overall survival of LUAD patients was constructed with robust prognostic capability. The ATNKGS high risk group was related to significantly worse OS outcomes than those in the low-risk group, which were verified in TCGA and four GEO datatsets. A nomogram combining the ATNKGS risk score with clinical TNM stage achieved the optimal prediction performance. The single-cell RNA sequencing analysis revealed CTSL as an IRG of macrophage and monocyte. Moreover, though CTSL was an indicator for poor prognosis of LUAD patients, CTSL high expression group was associated with higher ESTIMATEScore, immune checkpoints expression, and lower TIDE score. Several immunotherapeutic cohorts have confirmed the response-predicting significance of CTSL in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment.

Conclusions

Our study provided an insight into the significant role of APC/T/NK cells-related genes in survival risk stratification and CTSL in response prediction of immunotherapy in patients with LUAD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03485-5.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Prognosis, Immunotherapy, Markers

Introduction

Lung cancer is recognized as a major health burden worldwide with high incidence and mortality rate. According to GLOBOCAN 2020, an estimated 2.21 million newly diagnosed lung cancer cases and 1.80 million lung cancer deaths occurred globally in 2020 [1]. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common histological subtype, which accounts for approximately 66% of lung cancer and 78% of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [2]. In recent years, both the survival outcomes of patients with early-stage and metastatic lung cancer have improved due to higher proportion of patients receiving radical treatment or the implement of novel anticancer drugs [3]. Immunotherapy, especially immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment, provides a new option for patients who have advanced-stage LUAD without targetable driving mutation [2]. Cell-based delivery systems have also emerged as promising strategies to improve cancer immunotherapeutic response [4]. Unfortunately, some early-stage patients still experienced early recurrence and metastasis [5–7]. Moreover, a large part of advanced-stage patients failed to show response to immunotherapy. It is still an urgent clinical demand to identify more potent biomarkers that can help clinicians to identify LUAD patients with higher risk of experiencing poorer survival outcomes and who may potentially benefit more from ICI treatment [8].

As the development of molecular biology technology continues, a growing body of knowledge has been gained about molecular interactive network, tumor microenvironment (TME), as well as the role of immune-infiltrating cells in tumor progression and defense [9–11]. Antigen processing and presentation is a complex process and plays a key role in immune response [12]. Antigen-presenting cells (APC) comprise the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), dendritic cells (DC), B cells, and thymic epithelial cells [13–15]. Monocytes can further differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells to perform the function of antigen processing and presentation [16]. The antigen processing and presentation subsequently induces T-cell adaptive responses and mediates tumor-killing process [17]. Additionally, the activation and function of effector T cells triggered by the T-cell receptor signaling pathway are deemed as the central focus of anti-tumor immunotherapy [18, 19]. Apart from adaptive immune system where APC and T cells belong to, NK cells serve as important innate immunity effectors and can be activated without prior sensitization [20]. NK cells are implicated in mediating cytotoxicity and eliminate tumor cells both in the lung tissue and peripheral blood [21]. Together, APC/T/NK cell is potent immune soldiers contribute tremendously to fighting against tumor invasion.

In this study, by investigating the key genes in three APC/T/NK cell-related Kyoko encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathways, we aimed to identify an APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature (ATNKGS) for risk stratification and to identify potential markers for immunotherapeutic response prediction in LUAD patients by an integrated analysis of bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing.

Method

LUAD datasets and preprocessing

The mRNA expression profile of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-LUAD samples with complete survival information (n = 497) was obtained from UCSC Xena website (https://xenabrowser.net/) for the construction of ATNKGS-related risk model (TCGA discovery cohort) and internal validation (TCGA validation cohort) at a ratio of 6:4, the corresponding mutation, methylation data were also downloaded for relevant analysis. The gene expression and clinical data of four GEO cohorts GSE11969 (n = 90), GSE31210 (n = 226), GSE37745 (n = 106), and GSE50081 (n = 127) were downloaded from GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) to externally validate the prognostic capability of the ATNKGS-related risk model. Other two GEO cohorts GSE126044 (n = 16) and GSE135222 (n = 24) containing patients with advanced-stage NSCLC receiving programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) therapy were obtained to validate the prognostic value of the risk model in predicting immunotherapeutic response. A total of 247 APC/T/NK cells-related genes were collected from three KEGG pathways in KEGG database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg): hsa04612 (antigen processing and presentation), hsa04660 (T-cell receptor signaling pathway), and hsa04650 (natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity). Among them, 196 genes simultaneously existed in all seven cohorts mentioned above and were used for further gene screen and risk model construction (Table S1). In the process of constructing ATNKGS risk model and its validation, the expression profile of 196 APC/T/NK cells-related genes in all these seven cohorts was normalized using the R package “sva” to remove batch effect and reduce inter-cohort heterogeneity. Moreover, single-cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing data of three LUAD samples from GSE117570 were downloaded for the identification of key immune cell-related genes (IRG). The detailed information of all datasets we used in this study are summarized in Table S2.

Construction and validation of ATNKGS-related risk model

For the construction of ATNKGS-related risk model, the TCGA-LUAD samples were divided into discovery cohort (n = 298) and validation cohort (n = 199) at a ratio of 6:4 randomly. Univariate Cox regression analysis of the 196 APC/T/NK cells-related genes was performed to explore their prognostic value in LUAD patients from TCGA discovery cohort; then, those with p < 0.05 were considered as potential prognostic genes and were entered into the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm with a tenfold cross-validation to detect the optimal prognostic genes using “glmnet” R package, those with the minimized lambda were screened out. Then, the formula of ATNKGS was built by a linear combination of the expression of selected gene which was weighted by their corresponding regression coefficients from LASSO results as follows: ATNKGS Risk score = ∑i Coefficient of (i) × Expression of gene (i).

All patients in the TCGA discovery cohort were divided into either a high-risk or low-risk group according to the optimal cutoff point of ATNKGS risk score which was determined by the “surv_cutpoint” function of the “survminer” R package. The TCGA validation cohort and four GEO cohorts including GSE11969, GSE31210, GSE37745, and GSE50081 were applied to validate the prognostic value of the ATNKGS risk model internally and externally, each validation cohort was divided into high- and low-risk group by the uniformed cutoff value which was determined in the TCGA discovery cohort. The Kaplan–Meier curves of the six cohorts with log-rank test were presented. Besides, the pooled forest plot was generated via RevMan 5.3 software.

Establishment of a nomogram predicting the prognostic value

To verify the independent prognostic value of ATNKGS-related risk model, the risk score of LUAD patients was put into Cox regression analysis, along with other clinical variates including age, gender, and clinical TNM stage. TCGA discovery cohort was set as the training cohort, TCGA validation cohort was set as the validation cohort. The variates with p value < 0.05 in univariate Cox analysis were put into multivariate analysis, the final variates with p value < 0.05 in multivariate Cox analysis were deemed as independent prognostic factors and were used to build a combined prognostic model and corresponding nomogram for better prognostic prediction of LUAD patients. The time-dependent C-index curves of the combined model, risk score, and each prognostic clinical factor were generated. One-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS calibration curves of the nomogram were performed to test the consistency of the predicted values and the actual outcomes. The area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for the combined model, risk score, and each prognostic clinical factor were drawn and compared via the “timeROC” R package.

Functional enrichment and immune landscape of ATNKGS risk model

Functional enrichment analysis was applied to investigate the underlying mechanism behind the distinct prognostic outcomes when divided by the ATNKGS risk model. Genes that were strongly correlated with the ATNKGS-related risk score were identified under the criteria of Spearman |R|> 0.5 as well as p value < 0.05. Next, gene ontology biological process (GOBP) and KEGG analysis were conducted using “clusterProfiler” and “org.Hs.eg.db” R packages.

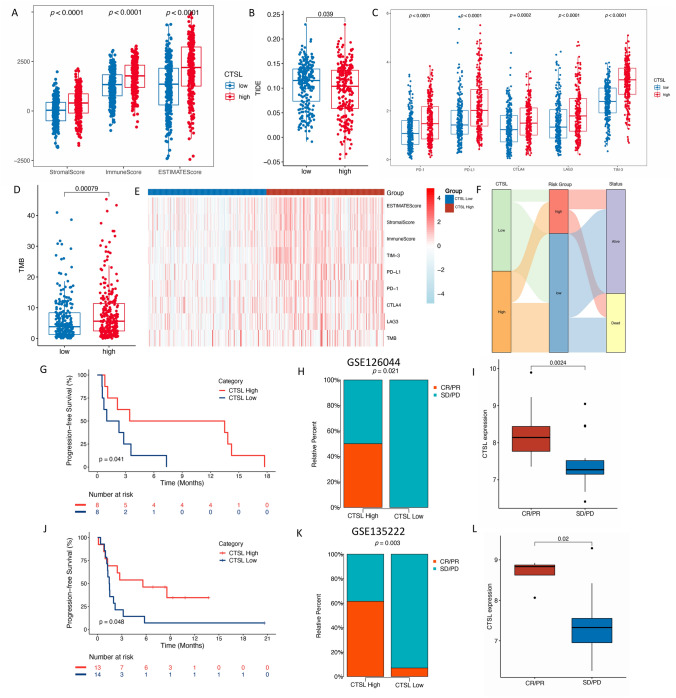

Next, the immune landscape of ATNKGS risk model was investigated. ImmuneScore, StromalScore, and ESTIMATEScore (defined as the sum of ImmuneScore and StromalScore) of each LUAD sample were calculated using Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumors using Expression data (ESTIMATE) algorithm to indicate the infiltration status of immune cells and stromal cells as well as tumor purity, the differences between the two risk groups were compared. The expression of five immune checkpoints PD-1, PD-L1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), and T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-3 (TIM-3) in the two risk groups were also investigated. Tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion (TIDE) algorithm was also used to predict potential ICI therapy response. Data of GSE126044 and GSE135222 cohorts were obtained for clinical validation on the prognostic value of ATNKGS-related risk model in ICI treatment outcome of patients with NSCLC using the same cutoff value as mentioned above.

Sensitivity analysis of ATNKGS-based anti-cancer treatment

Apart from immunotherapy, we also used “oncopredict” R package to calculate the semi-inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 198 types of chemotherapeutic or targeted agents and to compare their sensitivity on each patient of ATNKGS high- or low-risk groups in the TCGA-LUAD cohort.

Analysis of genomic mutation and methylation profile

The genomic somatic mutation information of 132 LUAD samples in the ATNKGS high-risk group and 356 samples in the low-risk groups of the TCGA-LUAD cohort were available and visualized by “maftools” R package. The median value and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of TMB level as well as variants per sample in the two risk groups were compared. The genomic methylation data of 430 LUAD patient samples (Illumina Infinium 450 K DNA methylation data) among 497 patients with RNA-seq data analysis were available. To correct the probe design bias, the beta-value matrix was normalized using “ChAMP” R package. The methylation level in the ATNKGS low-risk and high-risk groups was compared. In addition, the relevance of mRNA expression of the 16 APC/T/NK cells-related genes with their respective methylation profile was evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis.

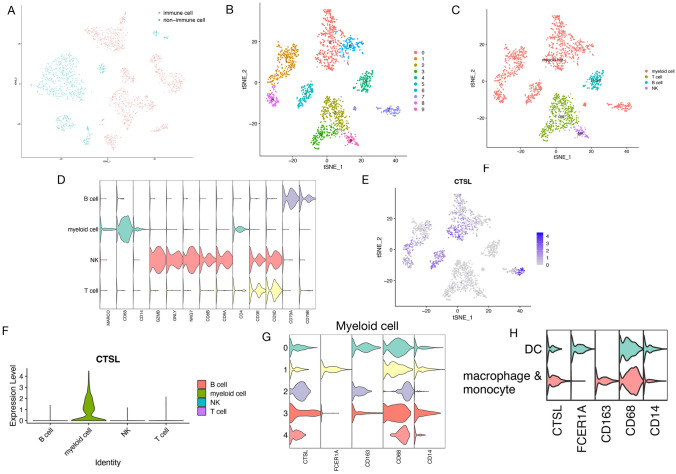

Identification of IRG by scRNA-seq analysis

After evaluating the distribution of "nFeature_RNA," "nCount_RNA," and "percent.mt," cells with more than 30% of mitochondrial gene and those with gene number in each cell less than 200 were removed. The top 2000 variably expressed genes were selected to conduct principal component analysis (PCA). Cell clustering was determined using T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) algorithm under a resolution of 0.5 and principal components (PC) of 20. Next, we used the expression level of PTPRC (CD45) to differentiate immune cells from non-immune cells (avg.exp.scaled > −0.5). Canonical marker gene expressions were used for cluster annotation (T cell: CD3E and CD3D; NK cell: GZMB, GNLY, and NKG7; B cell: CD79A and CD79B; and myeloid cell: MARCO, CD14, and CD68). Then, myeloid cells were further divided into macrophage and monocyte cell and dendritic cell by their respective canonical marker gene expressions. IRG among the 16 APC/T/NK cell-related genes was identified as differentially expressed genes with a |log2 (fold change [FC])|> 1.5 and adjusted p value (FDR) < 0.01.

Immunotherapeutic response prediction of IRG in LUAD patients

According to the expression of the selected IRG, all TCGA samples were divided into high expression group and low expression group as compared to its median expression value. The GOBP and KEGG functional enrichment analyses were conducted in the two groups first. Then, the ssGSEA algorithm was utilized to estimate the abundance profile of 28 types of immune cells in LUAD cases. The comparison of immune cell infiltration level in the IRG high and low expression groups was evaluated. A series of immunotherapeutic prediction indicators including TIDE score, ImmuneScore, StromalScore, ESTIMATEScore, TMB level, mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH), and five aforementioned immune checkpoints including PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, LAG3, and TIM-3 were calculated to compare the immunotherapeutic response of LUAD patients in IRG high expression group and low expression group. The data of GSE126044 and GSE135222 immunotherapy cohorts were again utilized for clinical validation for the prognostic probability of IRG on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) outcome prediction of patients with NSCLC receiving ICI treatment. Additionally, the response of each patient in these two cohorts was collected including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). Apart from IRG high and low expression group, the correlation of direct expression level of IRG and immunotherapeutic response of these patients were studied.

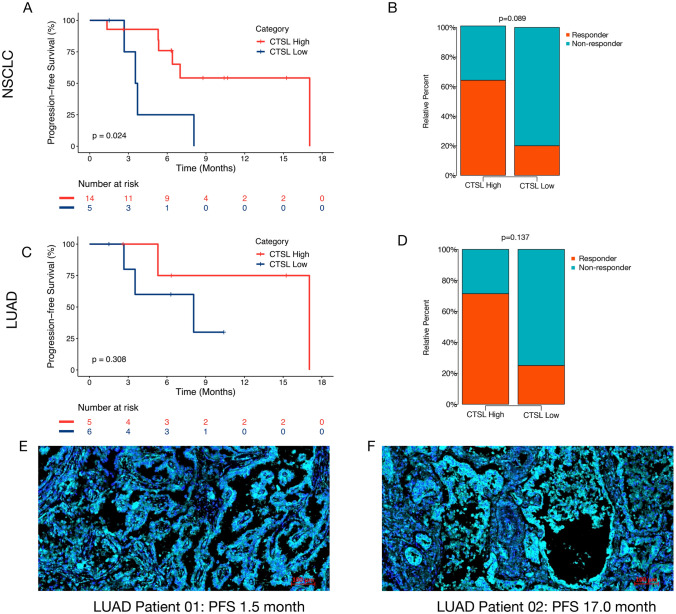

Immunofluorescence staining

To verify the prognostic value of IRG on the efficacy of immunotherapy in real world, we collected the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) 4-μm tissues of an external cohort of 19 patients with advanced NSCLC receiving treatments of ICI combined with chemotherapy from Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, and then performed immunofluorescence staining on the antibody against CTSL (1:100, ab203028, Abcam) which is an IRG identified in this study. 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was applied for cell nuclear visualization. Specimens were observed using a fluorescence microscope equipped for fluorescence analysis (ZEN 3.3).

Then, these 19 patients were divided into high CTSL expression group and low CTSL expression group by the threshold of the optimal cutoff value of the average cell intensity of CTSL expression in each individual patient. Then, the data were used to investigate the correlation between patients’ responses to ICI-combined treatment and patients’ PFS outcome.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were carried out via R software (version 4.1.0; https://www.r-project.org). The correlation between continuous variables was calculated by Spearman correlation analysis. The comparison of variables between the two groups was calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The median PFS, OS, and their corresponding 95%CIs were calculated via Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard ratios (HR) and their corresponding 95%CIs were analyzed with COX proportional hazards model, and p values were calculated by log-rank test. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of APC/T/NK cells-related genes and construction of ATNKGS-related risk model

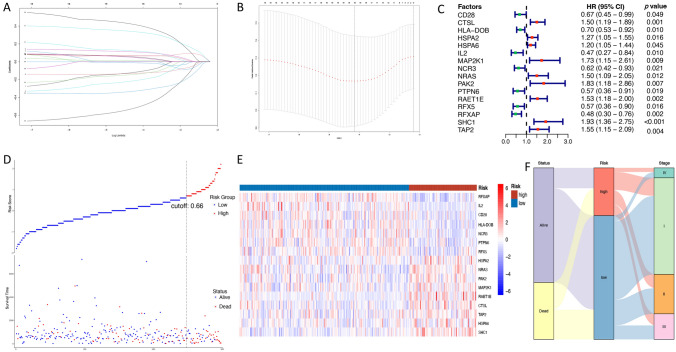

The TCGA discovery cohort (N = 298) was used to identify a potential prognostic signature. All 196 APC/T/NK cells-related genes were initially performed univariate Cox analysis; then, 19 genes were found to be significantly correlated with OS outcome (Table S3). After LASSO Cox regression algorithm, a total of 16 genes were screened out with a minimized lambda = 0.01578777. Thus, a final ATNKGS-related risk model containing 16 genes was established with a risk score formula as follows: risk score = (−0.113 × CD28 expression) + (0.065 × CTSL expression) + (−0.207 × HLA-DOB expression) + (0.109 × HSPA2 expression) + (0.052 × HSPA6 expression) + (−0.128 × IL2 expression) + (0.014 × MAP2K1 expression) + (−0.012 × NCR3 expression) + (0.120 × NRAS expression) + (0.045 × PAK2 expression) + ( −0.508 × PTPN6 expression) + (0.069 × RAET1E expression) + (−0.138 × RFX5 expression) + (−0.325 × RFXAP expression) + (0.333 × SHC1 expression) + (0.410 × TAP2 expression) (Fig. 1a, b). The univariate Cox analysis results of the final 16 APC/T/NK cells-related genes are presented in Fig. 1c. The function of the 16 genes is summarized in Table 1. Then, patients were divided into high-risk group (n = 83) and low-risk group (n = 215) by comparing their respective risk score with the optimal cutoff value of 0.6649351. The distribution of the risk scores and survival status is displayed in Fig. 1d. The 16 genes expression profile in the high- and low-risk groups is shown in Fig. 1e. The comparison of each of the 16 genes expression in the tumor sample and paracancerous sample is presented in Figure S1. The Sankey plot displayed the relationship among the risk groups, survival status, and clinical TNM stage (Fig. 1f). The ATNKGS-related high-risk group was observed with significant worse OS outcomes compared to the low-risk group (median OS: 2.1 vs 8.7 months, HR = 4.34 [95%CI 2.85–6.61], p < 0.001, Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

Construction of the ATNKGS in the TCGA discovery set. a Tenfold cross-validation partial likelihood deviance revealed by LASSO regression model. b LASSO coefficient profiles of selected 16 ATNKGS genes in the tenfold cross-validation. The vertical dotted lines were drawn at the optimal values by using the minimum criteria and 1-SE criteria. c The forest plot summarizing the impact of the expression of 16 ATNKGS genes on OS in the TCGA discovery set via univariate Cox regression analysis. d Distribution of ATNKGS risk group and survival status. The optimal cutoff value is determined as the cutoff value. e Heat map depicting the association between ATNKGS risk group and expression profile of 16 ATNKGS genes. f Sankey plot summarized the relationships among the survival status, ATNKGS risk groups, and clinical stage. ATNKGS, APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature; APC, antigen-presenting cells; and OS; overall survival

Table 1.

Functions of 16 APC/T/NK cells-related genes in the risk model

| No | Gene | Full name | Function | Risk coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CD28 | CD28 Molecule | Involved in T-cell proliferation and survival, cytokine production, and T-helper type-2 development | − 0.113136981 |

| 2 | CTSL | Cathepsin L | Involved in degradation of intracellular and endocytosed proteins in lysosomes, intracellular protein catabolism, and cancer-associated osteolysis, plays a critical role in general protein turnover, antigen processing and bone remodeling. | 0.064587049 |

| 3 | HLA-DOB | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DO beta | Involved in antigen presentation | − 0.206810674 |

| 4 | HSPA2 | Heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 2 | Involved in negative regulation of inclusion body assembly and protein refolding | 0.108632805 |

| 5 | HSPA6 | Heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 6 | Involved in cellular response to heat and protein refolding | 0.051738434 |

| 6 | IL2 | Interleukin 2 | Involved in T-cell proliferation and other activities related to the regulation of immune response | − 0.127732431 |

| 7 | MAP2K1 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 | Involved in signal transduction of MAPK/ERK cascade | 0.01437721 |

| 8 | NCR3 | Natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor 3 | Involved in stimulate and control NK cells cytotoxicity | − 0.012044342 |

| 9 | NRAS | NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase | Involved in intrinsic GTPase activity | 0.119585623 |

| 10 | PAK2 | P21 (RAC1) activated kinase 2 | Involved in cytoskeleton reorganization and nuclear signaling | 0.044919769 |

| 11 | PTPN6 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 6 | Involved in signal regulation of cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle, and oncogenic transformation | − 0.508377619 |

| 12 | RAET1E | Retinoic acid early transcript 1E | Involved in innate and adaptive immune responses | 0.069334685 |

| 13 | RFX5 | Regulatory factor X5 | Involved in activating transcription from class II MHC promoters | − 0.137512423 |

| 14 | RFXAP | Regulatory factor X-associated protein | Involved in activating transcription of MHC class II gene promoters | − 0.324721366 |

| 15 | SHC1 | SHC adaptor protein 1 | Involved in signal transduction, regulation of endothelial cell migration, and sprouting angiogenesis | 0.333458429 |

| 16 | TAP2 | Transporter 2, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member | Involved in antigen presentation, molecules, and peptides transportation | 0.410152202 |

Resource: https://www.proteinatlas.org and https://www.genecards.org

Fig. 2.

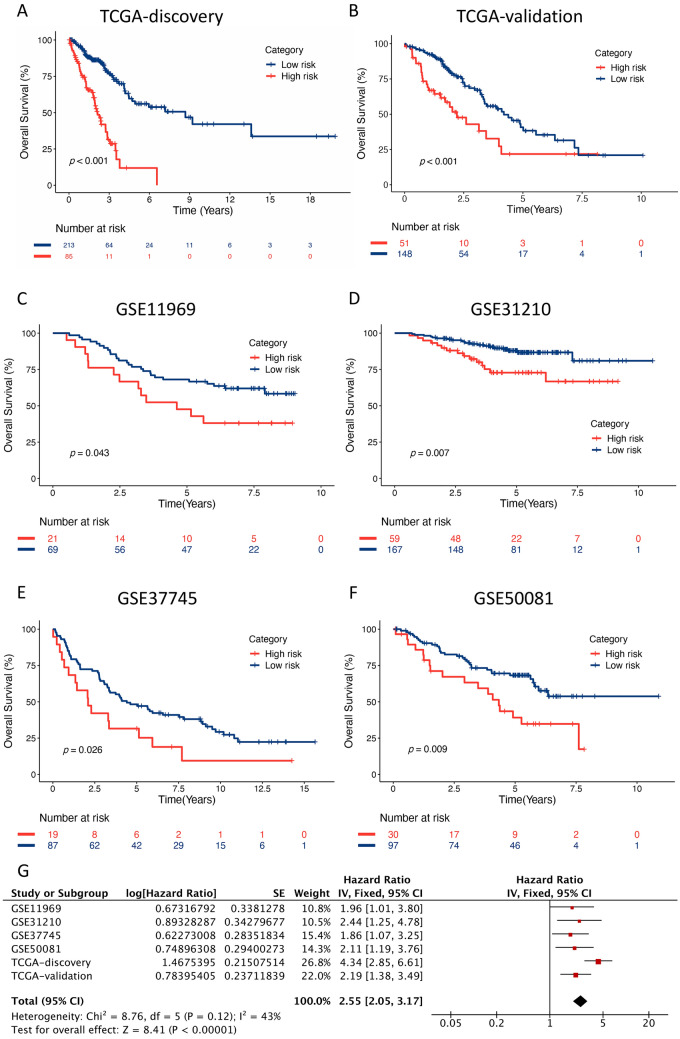

Kaplan–Meier curves of the ATNKGS risk group in TCGA discovery, TCGA validation, and four independent GEO cohorts. a TCGA discovery (n = 298), b TCGA validation (n = 199), c GSE11969 (n = 90), d GSE31210 (n = 226), e GSE37745 (n = 106), f GSE50081 (n = 127), and g a meta-analysis based on TCGA and GEO cohorts. ATNKGS, APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature and APC, antigen-presenting cells

Validation of the prognostic value of ATNKGS-related risk model in independent cohorts

The TCGA validation cohort and four independent GEO cohorts (GSE11969, GSE31210, GSE37745, and GSE50081) were applied to validate the prognostic significance of the ATNKGS-related risk model. The baseline patient characteristics of the TCGA and GEO cohort are listed in Table S4. The risk score of each individual patient was calculated using the same formula determined in TCGA discovery cohort. Each GEO cohort was divided into the high-risk group and the low-risk group by the same cutoff value of 0.6649351. Then, Kaplan–Meier curve with log-rank test verified that patients in the high-risk group had significantly worse OS outcomes than those in the low-risk group: TCGA validation set (Fig. 2b, HR = 2.19, 95%CI 1.38–3.49, p < 0.001); GSE11969 (Fig. 2c, HR = 1.96, 95%CI 1.01–3.80, p = 0.043); GSE31210 (Fig. 2d, HR = 2.44, 95%CI 1.25–4.78, p = 0.007); GSE37745 (Fig. 2e, HR = 1.86, 95%CI 1.07–3.25, p = 0.026); and GSE50081 (Fig. 2f, HR = 2.11, 95%CI 1.19–3.76, p = 0.009). The pooled forest plot is displayed in Fig. 2g with a pooled HR of 2.55 (95%CI 2.05–3.17, p < 0.001).

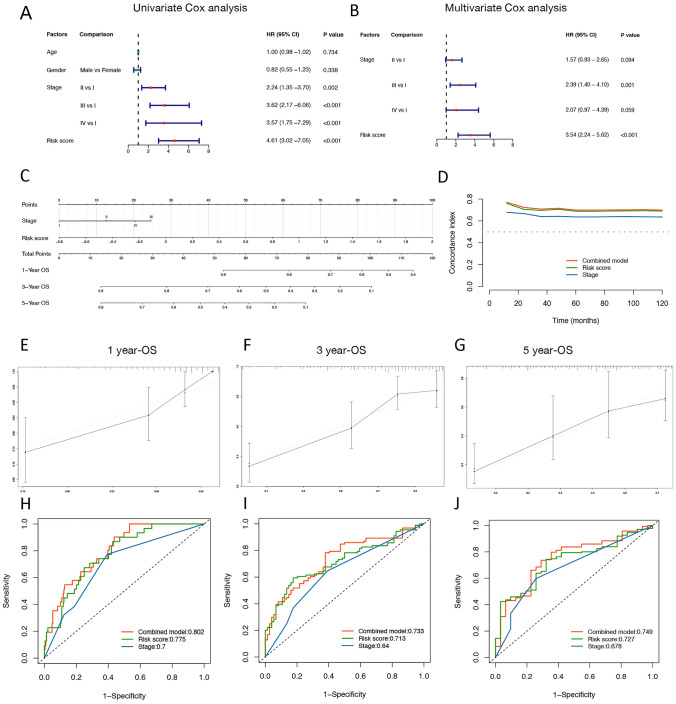

Construction of a nomogram for LUAD

Since ATNKGS was found to be significantly associated with OS as presented in the Kaplan–Meier curve, we sought to investigate its independent role in predicting OS outcome after excluding the influences of key confounding factors. The ATNKGS risk score, age, gender, and clinical TNM stage were enrolled to perform Cox regression analysis (Fig. 3a, b). Only ATNKGS risk score and TNM stage entered into the multivariate Cox analysis, and the ATNKGS risk score was identified as a meaningful risk factor for OS which was independent of TNM stage. A nomogram combining ATNKGS risk score with TNM stage was built based on the multivariate Cox analysis results (Fig. 3c). Time-dependent C-index curves of the combined model, ATNKGS risk score, and TNM stage demonstrated the better performance of the combined model than either separate risk factors (Fig. 3d). Calibration plots of the 1-year OS, 3-year OS, and 5-year OS indicated the robust predictive capability of the combined model (Fig. 3e–f). The ROC curves also showed the favorable predicting performance of the combined model with the AUC of 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC being 0.802, 0.733, and 0.749, respectively (Fig. 3h–j). The AUC of 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC of the ATNKGS risk model was 0.775, 0.713, and 0.727, respectively. Those of TNM stage were 0.7, 0.64, and 0.678, respectively. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS predicting value of the combined model was also verified in the TCGA validation cohort (Figure S2).

Fig. 3.

Nomogram predicting the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of LUAD patients in the TCGA discovery cohort. a, b The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis. c The nomogram combining ATNKGS risk score and clinical stage for predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS of LUAD patients. d Time-dependent C-index plot of the combined model, ATNKGS risk score, and clinical stage. e–g The calibration curve of the combined model for predicting OS of LUAD patients at 1, 3, and 5 years. X-axis referred to predicted OS value, y-axis referred to actual OS value. h–j The ROC curve of the combined model, ATNKGS risk score, and clinical stage in predicting OS of LUAD patients at 1, 3, and 5 years. ATNKGS, APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature; APC, antigen-presenting cells; and LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma

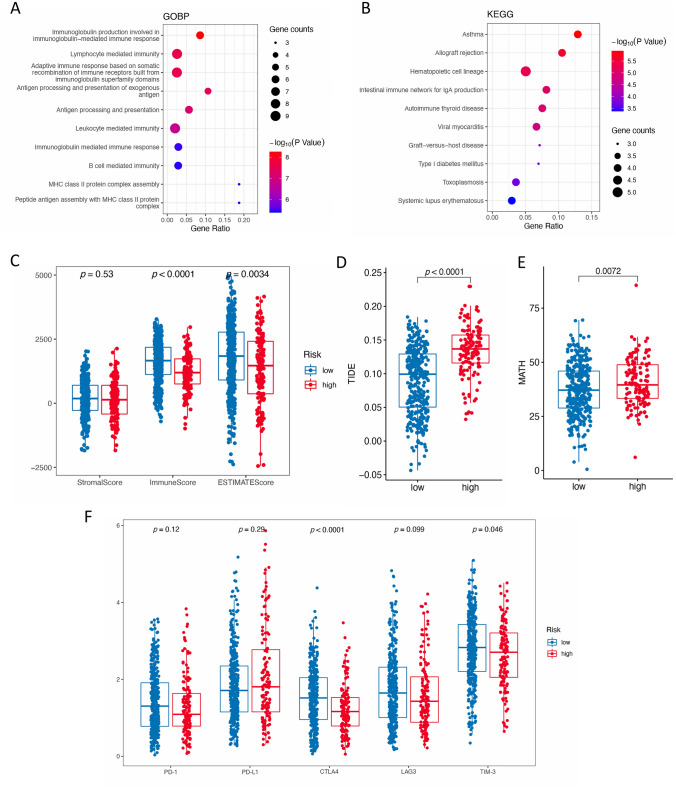

Biological pathways related to ATNKGS

A total of 48 genes that have strong correlation with the ATNKGS risk score were identified including 34 negatively related genes and 14 positively related ones (Table S5). Thereafter, GO and KEGG analyses on these genes were performed (Fig. 4a, b). The results showed that in the aspect of GOBP, they were most involved in the immunoglobulin production involved in immunoglobulin-mediated immune response, immune cell-mediated immunity and immune response, antigen processing and presentation, etc. In KEGG, they were most involved in immune-caused diseases such as asthma and allograft rejection, hematopoietic cell lineage, etc.

Fig. 4.

Functional enrichment analysis and immunotherapy predictive value of the ATNKGS. a GOBP; b KEGG; c the correlation between ATNKGS risk group and StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore; and d–g the correlation between ATNKGS risk group and TIDE d, MATH e, and five immune checkpoints f, respectively. ATNKGS, APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature; APC, antigen-presenting cells; GO, gene ontology; BP, biological process; KEGG, Kyoko encyclopedia of genes and genomes; TIDE, tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion; MATH, mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity; and TMB, tumor mutation burden

Correlation of ATNKGS with immunotherapy response

In the immunotherapy response prediction analysis (Fig. 4c–g), the ATNKGS low-risk group possessed higher ImmuneScore (p < 0.0001) and ESTIMATEScore (p = 0.0034). The high-risk group has significantly lower expression of CTLA4 (p < 0.0001) and TIM-3 (p = 0.046), while no differences were observed in the other three markers. Significantly higher TIDE score (p < 0.0001) and higher MATH (p = 0.0072) were observed in the high-risk group. However, the predictive capability of the risk score formula in predicting patients’ sensitivity to immunotherapy in related patient cohorts using the same threshold of 0.6649351 was not quite satisfying. In the GSE126044 cohort, the high-risk group was also associated with worse PFS (HR = 2.71 [95%CI 0.37–9.71]) and numerically lower response rate (0% vs 37%), but the significance was not reached. So, it was in the GSE135222 cohort (Figure S3).

Sensitivity analysis of ATNKGS-based anti-cancer treatment

Via the “oncopredict” R package, the IC50 value of the 198 drugs for each TCGA-LUAD patients was calculated (Table S6). Figure S4A–F displays the results of six common chemotherapy agents including cisplatin, docetaxel, paclitaxel, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and 5-fluorouracil. By comparing the IC50 value of the two risk groups, we can see that the ATNKGS high-risk group was more sensitive to docetaxel (p < 0.001) and paclitaxel (p = 0.02), while no significant difference was observed between the sensitivity to other four common chemotherapy agents in the two risk groups. Figure S4G–L displays the IC50 comparison of six targeted drugs in the two risk groups. By ranking the difference between the IC50 of the high- and low-risk group, we discovered six top candidate novel drugs for ATNKGS low-risk group (Figure S4M–R) and high-risk group (Figure S4S–X), respectively.

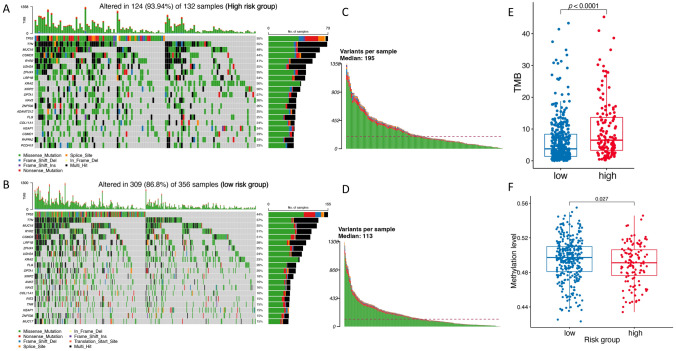

Mutation and methylation pattern of ATNKGS-related risk model

To explore the difference of the mutation and methylation data of the two risk groups and their respective impact on the function and prognostic value of the ATNKGS-related risk model, we collected certain data for further analysis. The mutation data were available in 488 TCGA-LUAD patients including 132 patients in high-risk group and 356 patients in low-risk group, based on which we depicted a landscape of the commonly mutated genes between the ATNKGS high-risk and low-risk group (Fig. 5a, b). The top three mutated genes in high- and low-risk groups were consistent which were TP53 (55% vs 44%), TTN (55% vs 37%), and MUC16 (48% vs 35%). In high-risk group, the median variant per sample was 195 which was higher than 113 in low-risk group (Fig. 5c, d). The high-risk group was associated with higher level of TMB than the low-risk group (5.43 [95%CI 6.21–8.87] vs 4.37 [95%CI 6.31–7.97] mutations/per megabase, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5e). The high-risk group has significantly higher fraction of altered genome compared to low-risk group (p = 0.018) (Figure S5A–B). We also analyzed and compared the genomic alterations data of these 16 genes between these two groups, NRAS and SHC1 have significantly higher altered event frequency in high-risk group (NRAS: p = 0.008 and SHC1: p = 0.048), while no significant difference was found in the other 14 genes (Figure S5C, Table S7). Additionally, the methylation data were available in 430 patients in the TCGA-LUAD cohort. Our finding revealed that methylation was more frequently observed in ATNKGS low-risk group (Fig. 5f). No correlation between mRNA expression and methylation was observed in the 15 APC/T/NK cells-related genes discovered in this study, while the methylation data of another gene HSPA6 were not available (Figure S6).

Fig. 5.

Mutation and methylation pattern of ATNKGS-related risk model. a, b The mutation pattern of the ATNKGS high-risk and low-risk group. c, d Variants per sample in ATNKGS high-risk and low-risk group. e The correlation between ATNKGS risk group and TMB. f The correlation between ATNKGS risk group and methylation level. ATNKGS, APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature; APC, antigen-presenting cells; and TMB, tumor mutation burden

Identification of IRG by scRNA-seq

To identify valuable IRG, GSE117570 cohort with scRNA-seq data of three LUAD samples was utilized. After data progressing and screening, expression profiles of 3524 cells from three LUAD samples were obtained for subsequent analysis. Initially, 15 clusters were identified among all cells, after clarified the expression level of CD45 in all 15 clusters, 10 clusters were determined as immune clusters with a total of 2093 immune cells (Fig. 6a). After cluster annotation, cluster 0/1/5/6/7/8 belongs to myeloid cells, cluster 2/3 belonged to T cells, cluster 4 belongs to B cells, and cluster 9 belongs to NK cells, respectively (Fig. 6b–d, Table S8). Among the 16 APC/T/NK cell-related genes, CTSL was found to be specifically expressed in myeloid cells (Fig. 6e–f) and has meaningful value on immunotherapy later; therefore, we focused on CTSL in this study. We further dig into myeloid cell and perform the subtype analysis (Fig. 6g). According to the canonical marker gene expression, myeloid was further categorized into macrophage and monocyte (cluster 0/2/3/4) and dendritic cell (cluster 1). While macrophage and monocyte were difficult to differentiate from each other by analyzing the canonical marker gene expression. But it is still confirmed that there is a significant differential expression of CTSL in macrophage and monocyte than in dendritic cell (Fig. 6h). Kaplan–Meier curve of CTSL verified its adverse prognostic value. High CTSL expression group was associated with poor OS outcomes of patients with LUAD (Figure S5, HR = 1.45 [95%CI 1.08–1.95]; p = 0.013).

Fig. 6.

Identification of immune marker genes by single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. a t-SNE plot colored by immune and non-immune cluster. b t-SNE plot colored by clusters. c t-SNE plot annotated by immune cells. d Violin plot showing marker genes used to help cluster annotation. e The FeaturePlot of CTSL. f The expression level of CTSL in each cluster. g, h Violin plot showing marker genes used to help cluster annotation of the myeloid cell

The role of CTSL in functional enrichment analysis and prediction of immunotherapeutic benefits

In functional enrichment analysis, 35 genes that have strong positive correlation with CTSL expression and one negatively related gene were identified (Table S9). GOBP analysis revealed that these genes were closely correlated with the regulation and negative regulation of immune cell proliferation, cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, activation of immune response, etc. (Figure S8A). KEGG analysis showed that they were involved in complement and coagulation cascades, etc. (Figure S8B). The immune cell infiltrating analysis demonstrated that many important immune-activating cells such as activated CD8 T cells, macrophages, monocytes, and nature killer T cells were enriched in the CTSL high expression group, indicating more hot immune status in this group of patients (Figure S8C).

Given the enrichment of immune-related pathways correlated to CTSL and its close association with positive infiltrating immune cells in the tumor microenvironment, we subsequently discovered its value in predicting immunotherapeutic benefits. Firstly, we calculated the association between enrichment of immune component and CTSL expression, the result showed that CTSL high expression group possessed higher StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore (p < 0.0001), indicating enrichment of immune component and higher immune activity in this population (Fig. 7a). The CTSL high expression group was also correlated with lower TIDE score, which indicated lower proportion of T-cell dysfunction and exclusion, and potentially superior response to ICI treatment (Fig. 7b). Higher expression of five immune checkpoints PD-1 (p < 0.0001), PD-L1 (p < 0.0001), CTLA-4 (p = 0.0002), LAG3 (p < 0.0001), and TIM-3 (p < 0.0001) and higher TMB (p = 0.00079) were consistently observed in the CTSL high expression group (Fig. 7c–e). The relationship among the groups divided by CTSL expression, groups divided by ATNKGS, and survival status was also investigated (Fig. 7f). A large proportion of patients in CTSL low expression group belongs to ATNKGS low-risk group.

Fig. 7.

Predictive value of CTSL on immunotherapy response. a The correlation between CTSL expression and StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATEScore in TCGA training cohorts. (B-D) The correlation between CTSL expression and TIDE b, five immune checkpoints c, and TMB d, respectively. e The summary heatmap of CTSL expression and immune markers mentioned above. f The Sankey plot revealing the relationship between CTSL expression, ATNKGS risk group, and live status. g–l Kaplan–Meier curve of median PFS and response to ICI treatment of CTSL high and low expression group in GSE126044 (g–i) and GSE135222 cohort (j–l). TIDE, tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion; TMB, tumor mutation burden; PFS, progression-free survival; and ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

The potent predictive capability of CTSL expression in predicting patients’ response to immunotherapy was observed in clinical validation. In the GSE126044 cohort (Fig. 7g–i), in CTSL high expression group, significantly better PFS outcome (HR = 3.34 [95%CI 0.99–11.28]; p = 0.041) and response rate to ICI treatment (50% vs 0%, p = 0.021) were observed. The median expression of CTSL is significantly higher in the response group than that in the non-response group (p = 0.0024). The OS data showed that patients in the CTSL high expression also achieved better OS outcome (HR = 3.41 [95%CI 0.99–11.80]; p = 0.041). The results of GSE135222 cohort were consistent with GSE126044 cohort (Fig. 7j–l), which showed that patients in the CTSL high expression group had significantly prolonged PFS compared to the low expression group (HR = 2.44 [95%CI 0.98–6.08]; p = 0.048); moreover, significantly higher response rate was observed in the high expression group (61.5% vs 7.0%, p = 0.003). The median expression of CTSL is significantly higher in the CR/PR group than that in the SD/PD group (p = 0.02).

External validation of prognostic value of CTSL with immunofluorescence staining

Moreover, our finding has been verified in a real-world immunotherapy cohort in our hospital. We collected the tumor sample of 19 patients with advanced lung cancer and then performed immunofluorescence staining. According to the average cell intensity of CTSL in each patient, the 19 patients were divided into high CTSL expression group and low CTSL expression group by comparing to the optimal cutoff value of average cell intensity of CTSL expression (610 fluorescence intensity units). The results showed that high CTSL expression group was associated with significantly prolonged PFS (p = 0.024, Fig. 8a) and numerically better response (Fig. 8b), responder refers as patients with CR, PR, or SD for more than 6 months. Among the 19 patients, 11 patients were with LUAD. In this sub-cohort of LUAD, the trend of getting more benefit in the CTSL high expression group can be observed even when the cutoff value was determined by median value of CTSL expression (Fig. 8c, d). Figure 8e displays that a patient who failed to benefit from ICI-combined treatment (PFS = 1.5 months) has a relatively lower expression of CTSL, while Fig. 8f displays a patient benefiting from ICI-combined treatment (PFS = 17.0 months) with a higher expression of CTSL in protein level. Together, our findings implied that patient with upregulated expression of CTSL might be more likely to benefit from anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, CTSL expression can serve as a promising indicator for immunotherapy.

Fig. 8.

Identification of the prognostic value of CTSL using immunofluorescence staining in an external cohort. a–b Kaplan–Meier curve of median PFS and response to ICI treatment of CTSL high and low expression group in 19 patients with NSCLC using the optimal cutoff value. c–d Kaplan–Meier curve of median PFS and response to ICI treatment of CTSL high and low expression group in 11 patients with LUAD using the median value as the cutoff point. e The immunofluorescence staining result of a patient with a relatively lower expression of CTSL (PFS = 1.5 months, CTSL average cell density = 477.2). f The immunofluorescence staining result of a patient with a relatively higher expression of CTSL (PFS = 17.0 months, CTSL average cell density = 725.3). Note, the color “cyan” indicated CTSL protein, the color “blue” indicated DAPI for nuclear visualization. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; and PFS, progression-free survival

Discussion

Due to intra-tumor heterogeneity, outcomes of LUAD vary even in patients with similar clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment regimens [2, 22]. It is a wise move and unmet clinical demand to investigate potent biomarkers or gene signatures for risk stratification and response prediction of LUAD patients receiving different treatment strategies, especially for ICI treatment which revolutionized treatment mode of lung cancer [8, 23]. In this study, by an integrated multi-dimension data analysis, we identified an ATNKGS-related risk model with robust capability for risk stratification of LUAD patients. The signature was confirmed as an independent risk indicator, then a nomogram combining the ATNKGS risk score with clinical TNM stage achieved the optimal prediction performance. Furthermore, CTSL was identified as a key IRG for macrophage and monocyte via single-cell RNA-seq analysis and was found to be a potent prognostic marker for predicting immunotherapy response of patients with lung cancer in several immunotherapy cohorts.

The ATNKGS was constructed based on 16 APC/T/NK cells-related genes. The ATNKGS risk score of each patient with NSCLC enrolled in this study was calculated using the same formula mentioned above, the high- and low-risk groups of each cohort were determined by the uniform cutoff value of 0.6649351. The potent prognostic capability of the ATNKGS-related risk model was verified in TCGA-LUAD (both the discovery and validation cohorts) and four extra GEO cohorts including GSE11969, GSE31210, GSE37745, and GSE50081 cohorts, patients in the high-risk group had significantly worse OS than those in the low-risk group.

The GOBP and KEGG functional enrichment analyses of ATNKGS were evaluated, the results showed that genes correlated with ATNKGS are mainly involved in immune response and immune-related signaling pathways. Intra-tumor heterogeneity plays a role in drug resistance, malignancy progression, and associated with poor survival [24]. Our finding also confirmed this point of view since the correlation analysis with MATH showed that the ATNKGS high-risk group was characterized with significantly higher intra-tumor heterogeneity. Among the five immune checkpoints, CTLA4 and TIM-3 were significantly downregulated expressed in the ATNKGS high-risk group. As we can see, CD28 is one of the 16 genes in ATNKGS, it is involved in prompting T-cell proliferation/activation/survival and production of cytokine. CD28 and CTLA4 share similar structure but exert opposing effects on T-cell stimulation by competitively binding to CD80 and CD86 [25], which might partly explain the opposite relationship between CTLA4 and ATNKGS risk scores. No difference of the PD-L1 expression was observed between the high and low risk, which indicated that ATNKGS was independent of PD-L1 to predict survival. TIM-3 was found to function as a T-cell inhibitory receptor, whose expression indicated the dysfunctional or exhausted CD8 + T cells subset [26]. Targeting on TIM-3 has achieved some positive results in preclinical cancer models which showed resistance to CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade [27].

The results of drug sensitive analysis in this study might also provide some advice for clinical oncologist to make clinical decision regarding potentially effective drugs and personalized treatment strategies. Of note, the application of targeted drugs should be based on the positive corresponding driving gene alteration status, so the relationship between the risk groups and driving gene alteration needed to be explored in the future study. In addition, we provided some insight into the candidate novel agents for ATNKGS low-risk and high-risk group. Especially for patients in high-risk group who have poorer survival, novel drugs are needed to prolong their survival time. BI-2536 is an inhibitor targeting Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) which has emerged as an important regulator in mitotic regulation, a phase II study demonstrated that BI-2536 received a PR of 4.2% and manageable safety in relapsed NSCLC [28, 29]. SCH772984 is an inhibitor targeting on extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), which was found to be able to suppress the signaling of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and cancer cell proliferation [30, 31]. While these agents are under clinical development and have no application for lung cancer currently, further effort should be made to investigate their potency.

In the analysis of the mutation and methylation data of the two risk groups, ATNKGS high-risk group was found to have a higher mutation profile, the result was consistent with the previous finding that in the context without ICI treatment, higher TMB was associated with poorer survival in many cancer types including NSCLC [32]. While the methylation data showed that ATNKGS low-risk group was associated with higher methylation level, which might indicate methylation modifications downregulate certain genes expression and suppress potential cancer progression. While the methylation profile was unrelated to the mRNA expression of the APC/T/NK cells-related genes in this study, which indicated that the expression regulation mechanisms of these genes do not depend on methylation modifications. Further efforts should be made to discover underlying mechanisms.

Among the 16 genes of ATNKGS, seven genes (CTSL, HLA-DOB, HSPA2, HSPA6, RFX5, RFXAP, and TAP2) were from antigen processing and presentation pathway, three genes (CD28, IL2, and PAK2) were from the T-cell receptor signaling pathway, three genes (NCR3, RAET1E, and SHC1) were from the natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity pathway, besides three genes (MAP2K1, NRAS, and PTPN6) were in both the T and NK cell-related pathway. Next, the single-cell sequencing analysis of three LUAD samples was applied to identify the key IRG, when CTSL was identified as a macrophage- and monocyte-related gene. Though ATNKGS was verified as a robust model for predicting the OS outcome of LUAD patients, its ability to predict immunotherapy response was not satisfying. Nevertheless, this has been made up by the value of CTSL.

Interestingly, the dual role of CTSL was discovered who act as a robust prognostic indicator for both poor prognosis and better immunotherapeutic response of LUAD patients simultaneously. The previous study has proposed that immune cell can confer positive or negative impact on patient survival outcomes depending on cell type, abundance, and functional orientation [33]. So were genes, other genes such as SMARCA4 has also found to exert an impact on poor outcomes and better sensitivity to immunotherapy for patients with lung cancer at the same time [34]. In this study, apart from the immune response and immune-related pathways, the genes that have positive correlation with CTSL expression were also implicated in cytokine-mediated signaling pathway. Immune cells communicate with each other through the exchange of secreted cytokines and chemokines. The cytokine-/chemokine-mediated communication plays a crucial role in the normal function of TME and antitumor activity [35, 36]. Besides, the complement and coagulation cascades were discovered to have close connection with CTSL from the KEGG results. The function of complement system in immunity regulation and immunosuppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment has been identified in the previous studies [37]. It has also been proposed that the coagulation and immune systems are directly linked with each other by mechanism like interleukin-1α activation by thrombin. All these evidences demonstrated the close but complicated relationship between CTSL and human immunity as well as the tumor microenvironment.

Cathepsin L (CTSL) is a member of the cysteine protease family, it plays a major role in degradation of intracellular and endocytosed proteins in lysosomes, intracellular protein catabolism, and SARS-CoV-2 infection [38, 39]. On the one hand, the upregulation of CTSL commonly occurred in various human cancers including lung cancer and was also implicated to contribute to tumorigenesis, tumor growth, invasion, and poor prognosis [40]. The previous studies also reported that the higher expression of CTSL was significantly correlated with a shorter OS in lung cancer [41], which was consistent with our results. Additionally, CTSL has been found to be significantly related to cancer-associated osteolysis which adversely affected both the quality of life and life expectancy of cancer patients [42]. In the preclinical experiment, CTSL upregulation-induced EMT was found to be associated with chemotherapy resistance of A549 cells [43].

On the other hand, different from the adverse prognostic value of CTSL in predicting prognosis of lung cancer which has been confirmed by the previous study, its correlation with immune cells and immunotherapeutic response has not been proposed previously, our study was the first to highlight the immunotherapy predictive role of CTSL in lung cancer, and the higher expression of CTSL could serve as a potent biomarker of better immunotherapeutic response. We discovered that CTSL was highly expressed in monocyte and macrophage, was identified as a macrophage- and monocyte-related gene. According to the HPA website, CTSL belongs to macrophage cluster and is enriched in monocyte, which is consistent with our results. Monocyte and macrophage have inextricable connection with each other, both of which belong to APCs; moreover, macrophages can be differentiate from monocyte [16]. CTSL is involved in the key process of innate immune response, the key function of CTSL, degradation of proteins, is an important process of antigen processing and presentation. On the other side, CTSL can process and activate various cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-1β, IL-18, and MCP-1, which are important for recruiting immune cells and promoting inflammation. The results of functional enrichment analysis also revealed that genes having close relationship with CTSL are enriched in immune-activating pathways and antigen processing and presentation-related pathways, which support the immune-activating and protective function of CTSL. The attempt has been tried to discover small-molecule inhibitors targeted on cathepsin L, whose results are awaited [38, 42, 44].

Limitations existed in this study. The datasets we used in the analysis were based on public databases, large sample size, well-designed studies in the real world are warranted to testify our finding. Secondly, the mechanism underneath the dual role of CTSL needs further investigation with deeper experimental research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provided an insight into the significant role of APC/T/NK cells-related genes in survival risk stratification and CTSL in response prediction of immunotherapy in patients with LUAD.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the data donors and research groups of TCGA-LUAD, GSE11969, GSE31210, GSE37745, GSE50081, GSE126044, GSE135222, and GSE117570. We thank the public TCGA, GEO, and KEGG databases, as well as UCSC Xena website, thank the patients in Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College who provided samples in this study. We also would like to thank Wu et al.’s article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-021-01853-y) and He et al.’s article (https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac291) as Figures 2 and 3 in this study referred to the typesetting format of their articles.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen-presenting cells

- ATNKGS

APC/T/NK cells-related gene signature

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CTLA4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete response

- ESTIMATE

Estimation of stromal and immune cells in malignant tumors using expression data

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GOBP

Gene ontology biological process

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IRG

Immune-related gene

- KEGG

Kyoko encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- MATH

Mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity

- MPS

Mononuclear phagocyte system

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progressive disease

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death-ligand 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- scRNA

Single-cell RNA

- SD

Stable disease

- TIDE

Tumor immune dysfunction and exclusion

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

Authors’ contributions

YKS and XHH contributed to supervision, conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing—review and editing. LLH helped in data curation, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. NL helped in data curation, visualization, and writing—review and editing; TJX contributed to visualization and writing—review and editing. Le Tang contributed to writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and final approval.

Funding

This work was funded by China National Major Project for New Drug Innovation (2017ZX09304015) and Major Project of Medical Oncology Key Foundation of Cancer Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CICAMS-MOMP2022006).

Data availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the institutional ethical committee of Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (19–019/1804), and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Liling Huang, Ning Lou and Tongji Xie have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaohong Han, Email: hanxiaohong@pumch.cn.

Yuankai Shi, Email: syuankai@cicams.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thai AA, Solomon BJ, Sequist LV, et al. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2021;398(10299):535–554. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng H, Chen W, Zheng R, et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003–15: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(5):e555–e567. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding Y, Wang Y, Hu Q. Recent advances in overcoming barriers to cell-based delivery systems for cancer immunotherapy. Exploration. 2022;2(3):20210106. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L, Tang L, Dai L, et al. The prognostic significance of tumor spread through air space in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13(7):997–1005. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL et al. (2022) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 20(5):497–530 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhong Z, Zhi LZ (2021) Chinese Association for Clinical Oncologists MOBoCIE, Promotion Association for Medical Healthcare. [Clinical practice guideline for stage IV primary lung cancer in China(2021 version)]. 43(1):39–59

- 8.Niu M, Yi M, Li N, et al. Predictive biomarkers of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s40164-021-00211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79(18):4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao X, Xu J, Wang W, et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang L, Jiang S, Shi Y. Prognostic significance of baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of open phase III clinical trial data. Future Oncol. 2022;18(14):1679–1689. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MY, Jeon JW, Sievers C et al. (2020) Antigen processing and presentation in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 8(2). 10.1136/jitc-2020-001111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Roche PA, Furuta K. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(4):203–216. doi: 10.1038/nri3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakubzick CV, Randolph GJ, Henson PM. Monocyte differentiation and antigen-presenting functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(6):349–362. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hume DA, Irvine KM, Pridans C. The mononuclear phagocyte system: the relationship between monocytes and macrophages. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(2):98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Germic N, Frangez Z, Yousefi S, et al. Regulation of the innate immune system by autophagy: monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and antigen presentation. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(4):715–727. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jhunjhunwala S, Hammer C, Delamarre L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(5):298–312. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldman AD, Fritz JM, Lenardo MJ. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(11):651–668. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He J, Xiong X, Yang H, et al. Defined tumor antigen-specific T cells potentiate personalized TCR-T cell therapy and prediction of immunotherapy response. Cell Res. 2022;32(6):530–542. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivori S, Pende D, Quatrini L, et al. (2021) NK cells and ILCs in tumor immunotherapy. Mol Aspects Med 80:100870. 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100870 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zeng Y, Lv X, Du J (2021) Natural killer cell‑based immunotherapy for lung cancer: Challenges and perspectives (Review). Oncol Rep 46(5). 10.3892/or.2021.8183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Huang L, Jiang S, Shi Y. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for solid tumors in the past 20 years (2001–2020) J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00977-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reck M, Remon J, Hellmann MD. First-line immunotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6):586–597. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.01497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(5):323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esensten JH, Helou YA, Chopra G, et al. CD28 costimulation: from mechanism to therapy. Immunity. 2016;44(5):973–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acharya N, Sabatos-Peyton C, Anderson AC (2020) Tim-3 finds its place in the cancer immunotherapy landscape. J Immunother Cancer 8(1). 10.1136/jitc-2020-000911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Das M, Zhu C, Kuchroo VK. Tim-3 and its role in regulating anti-tumor immunity. Immunol Rev. 2017;276(1):97–111. doi: 10.1111/imr.12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stratmann JA, Sebastian M. Polo-like kinase 1 inhibition in NSCLC: mechanism of action and emerging predictive biomarkers. Lung Cancer (Auckl) 2019;10:67–80. doi: 10.2147/lctt.S177618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebastian M, Reck M, Waller CF, et al. The efficacy and safety of BI 2536, a novel Plk-1 inhibitor, in patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer who had relapsed after, or failed, chemotherapy: results from an open-label, randomized phase II clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(7):1060–1067. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d95dd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caiola E, Iezzi A, Tomanelli M, et al. LKB1 deficiency renders NSCLC cells sensitive to ERK inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(3):360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moschos SJ, Sullivan RJ, Hwu WJ, et al (2018) Development of MK-8353, an orally administered ERK1/2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. JCI Insight 3(4). 10.1172/jci.insight.92352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, et al. The association between tumor mutational burden and prognosis is dependent on treatment context. Nat Genet. 2021;53(1):11–15. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chifman J, Pullikuth A, Chou JW, et al. Conservation of immune gene signatures in solid tumors and prognostic implications. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):911. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2948-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenfeld AJ, Bandlamudi C, Lavery JA, et al. The genomic landscape of SMARCA4 alterations and associations with outcomes in patients with lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(21):5701–5708. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Altan-Bonnet G, Mukherjee R. Cytokine-mediated communication: a quantitative appraisal of immune complexity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(4):205–217. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozga AJ, Chow MT, Luster AD. Chemokines and the immune response to cancer. Immunity. 2021;54(5):859–874. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolev M, Markiewski MM. Targeting complement-mediated immunoregulation for cancer immunotherapy. Semin Immunol. 2018;37:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li YY, Fang J, Ao GZ. Cathepsin B and L inhibitors: a patent review (2010 - present) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2017;27(6):643–656. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1272572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao MM, Yang WL, Yang FY, et al. Cathepsin L plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and humanized mice and is a promising target for new drug development. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):134. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gocheva V, Zeng W, Ke D, et al. Distinct roles for cysteine cathepsin genes in multistage tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20(5):543–556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1407406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Wei C, Li D, et al. COVID-19 receptor and malignant cancers: association of CTSL expression with susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18(6):2362–2371. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.70172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudhan DR, Siemann DW. Cathepsin L targeting in cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;155:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han ML, Zhao YF, Tan CH, et al. Cathepsin L upregulation-induced EMT phenotype is associated with the acquisition of cisplatin or paclitaxel resistance in A549 cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(12):1606–1622. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dana D, Pathak SK (2020) A review of small molecule inhibitors and functional probes of human Cathepsin L. Molecules 25(3). 10.3390/molecules25030698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.