Abstract

A single-chain antibody (scAb) against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) integrase was expressed as a fusion protein of scAb and HIV-1 viral protein R (Vpr), together with the HIV-1 genome, in human 293T cells. The expression did not affect virion production much but markedly reduced the infectivity of progeny virions. The fusion protein was found to be incorporated into the virions. The incorporation appears to account for the reduced infectivity.

Viral protein R (Vpr) of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), a virion-associated accessory protein consisting of approximately 100 amino acids (11 to 16 kDa), is as abundant as Gag protein in virions (3, 4, 19, 29, 34). Virion-associated Vpr has been implicated in nuclear localization of the viral preintegration complex in nondividing cells (8). Vpr can incorporate into virions foreign proteins such as staphylococcal nuclease (SN) (33), HIV-2 protease (PR) (32), chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (23), HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) (30), HIV-1 integrase (IN) (7, 13, 30), and oligopeptides (25). This targeting property of Vpr makes possible a unique approach to the gene therapy against HIV-1 infection, termed capsid-targeted virion inactivation (CTVI; originally designed for inactivation of virus-like particles of yeast retrotransposon [1, 21]), which involves incorporation of Vpr fusion proteins with enzymes that are deleterious to viral components, such as nucleases, into progeny virions during viral assembly. The incorporated toxic enzymes destroy the viral structural molecules (RNA or proteins) within the progeny virions to reduce their infectivity (1).

It is not obvious what to choose as an antiviral fusion partner in the CTVI strategy. Because the strategy depends upon expression of proteins that may be deleterious to the host cells, their activity and specificity must be controlled in such a way as to affect virions but not affect host cell functions. An ideal fusion partner would be nontoxic to the host cells and efficiently inactivate virions from within. The anti-HIV-1 molecules tested as Vpr fusion proteins so far are SN (33) and oligopeptides (25). However, there is little evidence that the Vpr-SN proteins incorporated in the virions have significant antiviral activity (33). At present, the most eligible fusion partner against HIV-1 is an oligopeptide whose sequence is analogous to the PR-cleavage sequence at the junction of p24Gag and p2Gag of HIV-1 (24/2); Vpr-24/2 is incorporated into virions and completely abolishes virus infectivity—there is more than a 103-fold reduction (25). In an attempt to find an effective partner molecule, we selected an anti-HIV-1 IN single-chain antibody termed scAb2-19 to prepare a fusion protein with Vpr. scAb2-19 binds specifically to the region from amino acid 228 to amino acid 235 of HIV-1 IN, inhibits in vitro integration, and represses in vivo viral replication when it is expressed intracellularly before infection (11).

Expression of fusion proteins.

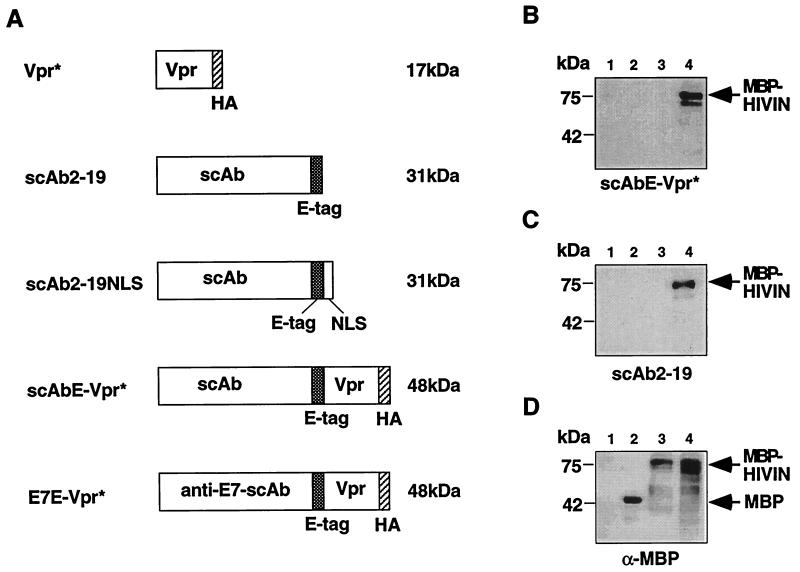

We constructed five expression plasmids, pC-Vpr*, pC-scAb2-19, pC-scAb2-19NLS, pC-scAbE-Vpr*, and pC-E7E-Vpr*, encoding proteins Vpr*, scAb2-19, scAb2-19NLS, scAbE-Vpr*, and E7E-Vpr*, respectively (Fig. 1A), by cloning an appropriate DNA fragment for each protein into pCXN2 (22). Vpr (HIV-1LAI) fused with hemagglutinin (HA) tag (YPYDVPDYA) at the C terminus is termed Vpr*. scAb2-19NLS (11) is scAb2-19 fused to a nuclear-localization signal peptide (LEPPKKKRKV) derived from simian virus 40 large T antigen. scAbE-Vpr* and E7E-Vpr* are Vpr* fusion proteins with scAb2-19 and a single-chain antibody reactive to human papillomavirus type 16 oncoprotein E7, respectively. All of the proteins could be expressed to a similar extent in human 293T cells (5) after transfection as determined by an immunoblot analysis (data not shown) and their molecular weights were estimated by the mobility on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1A). To determine subcellular localization of Vpr* and scAbE-Vpr*, the 293T cells transfected with pC-Vpr* and pC-scAbE-Vpr* were labeled with anti-HA antibody (rat, clone 3F10; Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and then were probed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody reactive to rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Organon Teknika, Cappel Division, Durham, N.C.). Vpr* and scAbE-Vpr* were localized primarily in the perinuclear region (data not shown), whereas scAb2-19 is localized primarily in the cytoplasm (11). This cellular localization of Vpr* as well as scAbE-Vpr* agrees with the findings of Withers-Ward et al. (28), but not with those of Lu et al. (14). The reason for this discrepancy in cellular localization of Vpr* is unknown.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of single-chain antibodies. (A) Schematic representation of recombinant proteins. Shaded and hatched boxes represent the E tag and HA tag, respectively. The molecular mass of each protein was estimated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and is shown on the right in kilodaltons. The illustrations are not proportionally drawn. (B to D) Analysis of binding of scAbE-Vpr* with HIV-1 IN. To determine the binding of scAb2-19 and scAbE-Vpr* with HIV-1 IN, HIV-1 IN immobilized on a membrane was probed with the 293T cell extract containing scAb2-19 (B) or scAbE-Vpr* (C) as well as an anti-MBP antibody (D). DH5α lysate (lane 1), purified MBP (New England Biolabs) (lane 2), and lysates of uninduced (lane 3) and induced (lane 4) DH5α carrying an expression vector for MBP-HIVIN were separated in an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The bound primary antibody molecules were probed and visualized. The positions of size markers (kilodaltons) are shown by the bars on the left of each panel. The positions of detected MBP and MBP-HIVIN are shown by the arrows on the right of each panel.

Binding of scAbE-Vpr* to HIV-1 IN.

A modified immunoblot analysis showed that scAb2-19 and scAbE-Vpr* bound specifically to HIV-1 IN (11) (Fig. 1B to D). In this analysis, HIV-1 IN fused with bacterial maltose-binding protein (MBP-HIVIN) immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane was probed by the 293T cell extract containing scAb2-19 or scAbE-Vpr*, the binding of which was detected with an anti-E tag (mouse; Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) or an anti-HA tag antibody, and then with goat polyclonal horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies to mouse or rat IgGs (Organon Teknika, Cappel Division). Both scAbE-Vpr* and scAb2-19 in 293T cell extracts detected MBP-HIVIN, but not MBP (Fig. 1B and C, compare lane 2 with lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, anti-MBP antiserum detected both MBP-IN and MBP (Fig. 1D, lanes 2 to 4), and the untransfected 293T cell extract detected no protein bands (data not shown).

Virion production.

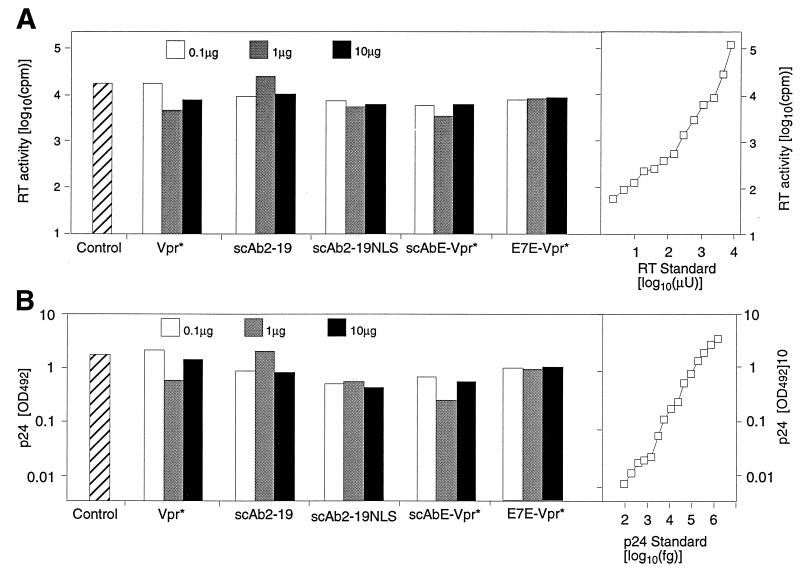

To test whether cellular expression of the recombinant Vpr* fusion proteins reduces virion production, we determined the quantity of virions released from the 293T cells harvested 48 h after cotransfection with pLAI (24), an HIV-1 infectious clone plasmid, together with each of the five expression plasmids by an RT assay and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for p24 antigen (Dainabot Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2). RT activity was determined essentially as described previously (18), except that [methyl-1′-2′-3H]TTP (Dupont, NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) and Flash Plate Plus (Dupont) instead of [α-32P]TTP and a DEAE membrane were used. Cellular expression of any one of the recombinant proteins did not affect virion production much, as assayed by RT activity or the amount of p24, independent of the amount of cotransfected DNA (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Amount of released virion in culture supernatants of the transfected 293T cells. Ten microliters of each culture supernatant of the 293T cells transfected with pLAI (10 μg), together with 0.1 μg (open bars), 1 μg (shaded bars), or 10 μg (solid bars) of pC-Vpr*, pC-scAb2-19, pC-scAb2-19NLS, pC-scAbE-Vpr*, or pC-E7E-Vpr* as shown below the bars, was centrifuged over a cushion of 20% sucrose to obtain a viral pellet. Each pellet was assayed for its RT activity (A) and amount of p24 (B). (A) The dashed bar on the left represents the control RT activity: the radioactivity obtained by an assay of the viral pellet recovered from 10 μl of the culture supernatant of the 293T cells transfected with 10 μg each of pLAI and pCXN2. To obtain a standard curve (right panel), various amounts of purified HIV-1 RT (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH) from 10 μU to 10 mU were analyzed. The radioactivity increased in proportion to the input RT quantities in the range of 102 to 105 cpm. Every radioactivity level obtained in the assay fell in this range. (B) The dashed bar on the left represents the control p24 amount: the optical density at 492 nm (OD492) obtained by ELISA on the viral pellet recovered from 10 μl of the culture supernatant of the 293T cells transfected with 10 μg each of pLAI and pCXN2. To obtain a standard curve (right panel), various amounts of purified HIV-1 p24 (102 to 106 fg) were analyzed. The OD492 increased in proportion to the input p24 quantities in the range of 0.01 to 3. Every OD492 obtained in the assay fell in this range.

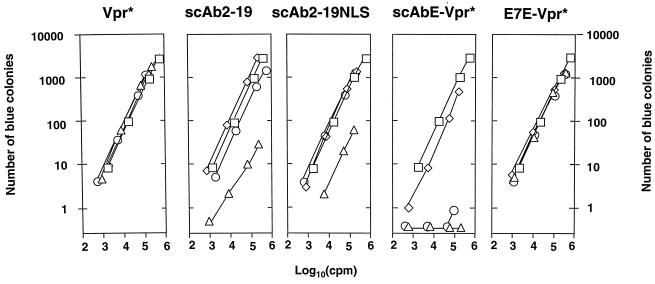

Infectivity of virions.

We measured the infectivity of the progeny virions in a single round of replication in a quantitative fashion by the multinuclear activation galactosidase indicator (MAGI) cell assay (10) (Fig. 3). The virions released in the presence of Vpr* and E7E-Vpr* were as infectious as the wild-type virions independent of the amount of cotransfected DNA. In contrast, the virions generated by cotransfection with pC-scAb2-19 (10 μg) or pC-scAb2-19NLS (10 μg) together with pLAI (10 μg) showed reductions in infectivity by about 60- and 17-fold, respectively. Furthermore, cotransfection of 293T cells with pLAI (10 μg) and pC-scAbE-Vpr* (10 μg) did not produce detectable infectious virus, showing a more than 103-fold reduction in infectivity at RT activity of around 105 cpm, where the difference in infectivity between this virus and the control virus was the largest.

FIG. 3.

Infectivity of the virions obtained by various cotransfections. Relationship between MAGI titers and quantities of input viral samples. The recombinant protein encoded by the expression plasmid with which 293T cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of pLAI is shown above each panel. In each panel, the MAGI titers of the virions released from the 293T cells cotransfected with 0.1, 1, and 10 μg of the expression plasmid, together with pLAI (10 μg), are represented by the diamond, circle, and triangle, respectively. The MAGI titers of the control virions which were produced from the 293T cells transfected with pLAI (10 μg) alone are represented by squares. In each transfection, the total amount of input DNA was adjusted to 20 μg with pCXN2, and the viral supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection. The y and x axes stand for MAGI titers (the number of blue colonies in each well) and RT activities of the input virions in counts per minute, respectively.

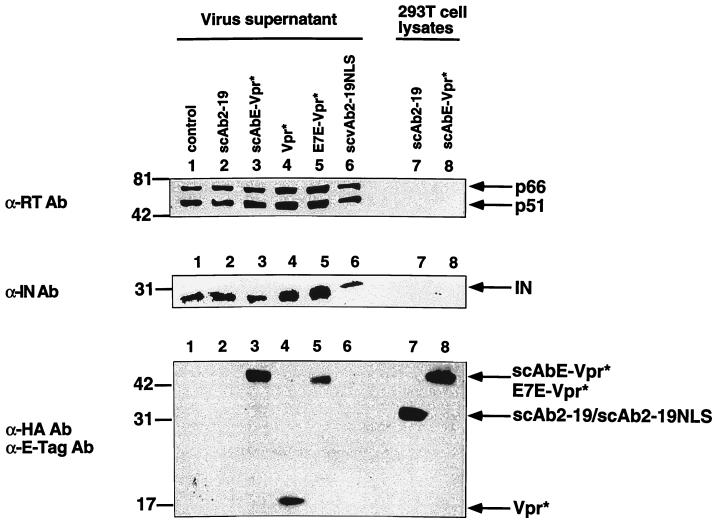

Analysis of virion proteins.

To analyze virion protein contents, the virions released into culture supernatants were collected by centrifugation over a cushion of 20% sucrose to purify virions and then were examined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4). The immunoblot analysis with an anti-RT (p66/p51) antibody (mouse monoclonal; Advanced Biotechnologies) as a primary antibody showed that all of the samples contained 66- and 55-kDa molecules of RT with almost the same intensity (Fig. 4, top panel, lanes 1 to 6). Similarly, an anti-IN antibody (mouse monoclonal, clone 2-19) detected the protein band corresponding to 31 kDa of IN in every sample to a similar extent (Fig. 4, middle panel, lanes 1 to 6). scAbE-Vpr*, Vpr*, and E7E-Vpr* were detected in virions (Fig. 4, bottom panel, lanes 3 to 5, respectively), while scAb2-19 or scAb2-19NLS was not (Fig. 4, bottom panel, lanes 2 and 6, respectively) detectable by the immunoblot analysis with anti-HA tag and anti-E tag antibodies, even with longer exposure of the film (data not shown). We concluded that the virions released from the 293T cells in the presence of any one of the five recombinant proteins contained RT and IN in as much abundance as the wild-type virions and that scAbE-Vpr* and E7E-Vpr*, but not scAb2-19 or scAb2-19NLS, were incorporated into the released virions as efficiently as Vpr*.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of viral proteins within virions. Each viral supernatant of the 293T cells cotransfected with 10 μg of pLAI together with 10 μg of pCXN2 (lane 1), pC-scAb2-19 (lane 2), pC-scAbE-Vpr* (lane 3), pC-Vpr* (lane 4), pC-E7E-Vpr* (lane 5), or pC-scAbE-Vpr* (lane 6) was collected, filtered, and centrifuged to obtain virions. The virion proteins, as well as proteins in the lysates of the 293T cells transfected with pC-scAb2-19 (lane 7) and pC-scAbE-Vpr* (lane 8), were separated in an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The proteins on it were investigated by antibodies (top, anti-RT; middle, anti-IN; bottom, anti-E tag plus anti-HA) followed by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase.

The data obtained in this study show that scAb2-19 (and scAb2-19NLS) and scAbE-Vpr*, when expressed together with the HIV-1 genome in 293T cells, reduced the specific infectivity of the progeny virions. The reducing effect was much greater with the latter than with the former. The greater effect with scAbE-Vpr* is probably accounted for by incorporation of the fusion protein into virions. The results suggest that single-chain antibodies against IN can be used in the CTVI strategy.

Our single-chain antibody is an eligible fusion partner in the CTVI strategy for two reasons. First, scAbE-Vpr* is incorporated into virions as efficiently as Vpr* (Fig. 4). Second, scAbE-Vpr* binds specifically to HIV-1 IN (Fig. 1B to D) without detectable cell toxicity (data not shown). In the latter situation, single-chain antibodies against unique and essential HIV-1 proteins such as PR, RT (15, 26), and IN (11, 12) seem to be excellent fusion partners and contrast with the reported partner molecules such as SN (33), which could affect the cell viability. Thus, scAbE-Vpr* seems to be a nearly ideal antiviral molecule in that it inhibits the viral replication without apparent cell toxicity at multiple steps in the viral replication cycle—the integration (11) and assembly (Fig. 3) steps in primarily infected cells. However, the feasibility of the intracellular immunization of lymphocytes in vivo with scAbE-Vpr* remains to be investigated; it may depend upon the efficiency of the gene transfer methods and host immune responses to the intracellular scAbE-Vpr*.

The reduced infectivity of the virions released from the 293T cells in the presence of scAbE-Vpr* appears to be due to its two distinct abilities to interfere with the viral assembly and budding and with integration in the subsequent infection. First, scAbE-Vpr* is likely to interfere with the correct folding of the viral structural proteins during viral assembly because scAb2-19, as well as scAb2-19NLS, reduced the infectivity of virions (Fig. 3) without being incorporated into virions (Fig. 4). Because IN is a C-terminal part of Gag-Pol polyprotein (27), the intracellular scAb2-19 or scAb2-19NLS interacting with the Gag-Pol polyprotein may interfere with the folding of the Gag-Pol polyprotein during the assembly of the Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins. Since detection of the intravirion scAb2-19 and scAb2-19NLS molecules failed even with a considerably sensitive immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4), the actual mechanism for the decrease in the viral infectivity by the intracellular expression of scAb2-19 or scAb2-19NLS is unknown. Second, scAbE-Vpr* decreased the infectivity of the progeny virions more effectively than scAb2-19 or scAb2-19NLS (Fig. 3). This is presumably because the incorporated scAbE-Vpr* neutralizes the function of intravirion IN. The products of the gag frame (MA, CA, and NC) are present in about 2,000 copies each per virion, whereas the products of the pol frame (RT and IN) are present in about 100 copies each per virion (27). Vpr is expected to be as abundant as the Gag proteins (9, 14, 16, 17). These facts lead to a rough estimate that scAbE-Vpr* is present at about 2,000 copies in each virion. This appears to be more than enough to neutralize the function of intravirion IN, which is present at about 100 molecules per virion. The neutralization may occur either within the virions or within a preintegration complex (6, 20) which includes IN (2, 6) as well as Vpr (8). This bifunctional feature of scAbE-Vpr* contrasts with the unifunctional characteristics of the previous fusion partners, which act only within virions (25, 31, 33).

Acknowledgments

We thank Tetsuro Matano (AIDS Research Center, NIID) and Mitsuaki Yoshida (Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo) for CD4-LTR/β-gal and 293T cells, respectively; Keith Peden (CBER, FDA) and Tadahito Kanda (Division of Molecular Genetics) for pLAI and cDNA for a single-chain antibody against E7 of human papillomavirus type 16, respectively; and Tadahito Kanda, Hiroshi Yoshikura (AIDS Research Center, NIID), and Kunito Yoshiike (National Institute of Health, Thailand) for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Masami Motai for secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by grants to Y.K. from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Human Science Foundation, and the Science and Technology Agency. N.O. is a recipient of a Research Resident Fellowship from the Japanese Foundation for AIDS Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boeke J D, Hahn B. Destroying retroviruses from within. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:421–426. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, McDonald T L, Pushkarskaya T, Tarpley W G, Stevenson M. Association of integrase, matrix, and reverse transcriptase antigens of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with viral nucleic acids following acute infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6125–6129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen E A, Dehni G, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Human immunodeficiency virus vpr product is a virion-associated regulatory protein. J Virol. 1990;64:3097–3099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3097-3099.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen E A, Terwilliger E F, Jalinoos Y, Proulx J, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Identification of HIV-1 vpr product and function. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuBridge R B, Tang P, Hsia H C, Leong P-M, Miller J H, Calos M P. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:379–387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farnet C M, Haseltine W A. Determination of viral proteins present in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complex. J Virol. 1991;65:1910–1915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1910-1915.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher T M R, Soares M A, McPhearson S, Hui H, Wiskerchen M, Muesing M A, Shaw G M, Leavitt A D, Boeke J D, Hahn B H. Complementation of integrase function in HIV-1 virions. EMBO J. 1997;16:5123–5138. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinzinger N K, Bukinsky M I, Haggerty S A, Ragland A M, Kewalramani V, Lee M A, Gendelman H E, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kewalramani V N, Park C S, Gallombardo P A, Emerman M. Protein stability influences human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpr virion incorporation and cell cycle effect. Virology. 1996;218:326–334. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimpton J, Emerman M. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2232–2239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2232-2239.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura, Y., T. Ishikawa, N. Okui, N. Kobayashi, T. Kanda, T. Shimada, K. Miyake, and K. Yoshiike. Intracellular expression of a single-chain antibody against integrase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibited the viral replication at both early and late steps of the viral life cycle. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Levy-Mintz P, Duan L, Zhang H, Hu B, Dornadula G, Zhu M, Kulkosky J, Bizub-Bender D, Skalka A M, Pomerantz R J. Intracellular expression of single-chain variable fragments to inhibit early stages of the viral life cycle by targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1996;70:8821–8832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8821-8832.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 13.Liu H, Wu X, Xiao H, Conway J A, Kappes J C. Incorporation of functional human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase into virions independent of the Gag-Pol precursor protein. J Virol. 1997;71:7704–7710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7704-7710.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y-L, Spearman P, Ratner L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R localization in infected cells and virions. J Virol. 1993;67:6542–6550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6542-6550.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maciejewski J P, Weichold F F, Young N S, Cara A, Zella D, Reitz M S, Jr, Gallo R C. Intracellular expression of antibody fragments directed against HIV reverse transcriptase prevents HIV infection in vitro. Nat Med. 1995;1:667–673. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahalingam S, Ayyavoo V, Patel M, Kieber-Emmons T, Weiner D B. Nuclear import, virion incorporation, and cell cycle arrest/differentiation are mediated by distinct functional domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 1997;71:6339–6347. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6339-6347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahalingam S, Khan S A, Jabbar M A, Monken C E, Collman R G, Srinivasan A. Identification of residues in the N-terminal acidic domain of HIV-1 Vpr essential for virion incorporation. Virology. 1995;207:297–302. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin M. Virological assay. In: Karn J, editor. HIV: a practical approach. Vol. 1. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1995. pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda Z, Chou M J, Matsuda M, Huang J H, Chen Y M, Redfield R, Mayer K, Essex M, Lee T H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 has an additional coding sequence in the central region of the genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6968–6972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller M D, Farnet C M, Bushman F D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71:5382–5390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natsoulis G, Boeke J D. New antiviral strategy using capsid-nuclease fusion proteins. Nature. 1991;352:632–635. doi: 10.1038/352632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park I W, Sodroski J. Targeting a foreign protein into virion particles by fusion with the Vpx protein of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:341–350. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peden K, Emerman M, Montagnier L. Changes in growth properties on passage in tissue culture of viruses derived from infectious molecular clones of HIV-1LAI, HIV-1MAL, and HIV-1ELI. Virology. 1991;185:661–672. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90537-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serio D, Rizvi T A, Cartas M, Kalyanaraman V S, Weber I T, Koprowski H, Srinivasan A. Development of a novel anti-HIV-1 agent from within: effect of chimeric Vpr-containing protease cleavage site residues on virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3346–3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaheen F, Duan L, Zhu M, Bagasra O, Pomerantz R J. Targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase by intracellular expression of single-chain variable fragments to inhibit early stages of the viral life cycle. J Virol. 1996;70:3392–3400. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3392-3400.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varmus H, Brown P. Retroviruses. In: Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 53–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Withers-Ward E S, Jowett J B M, Stewart S A, Xie Y-M, Garfinkel A, Shibagaki Y, Chow S A, Shah N, Hanaoka F, Sawitz D G, Armstrong R W, Souza L M, Chen I S Y. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr interacts with HHR23A, a cellular protein implicated in nucleotide excision DNA repair. J Virol. 1997;71:9732–9742. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9732-9742.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong-Staal F, Chanda P K, Ghrayeb J. Human immunodeficiency virus: the eighth gene. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1987;3:33–39. doi: 10.1089/aid.1987.3.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Conway J A, Hunter E, Kappes J C. Functional RT and IN incorporated into HIV-1 particles independently of the Gag/Pol precursor protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:5113–5122. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Conway J A, Kappes J C. Inhibition of human and simian immunodeficiency virus protease function by targeting Vpx-protease-mutant fusion protein into viral particles. J Virol. 1996;70:3378–3384. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3378-3384.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Kappes J C. Proteolytic activity of human immunodeficiency virus Vpr- and Vpx-protease fusion proteins. Virology. 1996;219:307–313. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, Kim J, Seshaiah P, Natsoulis G, Boeke J D, Hahn B H, Kappes J C. Targeting foreign proteins to human immunodeficiency virus particles via fusion with Vpr and Vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:3389–3398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3389-3398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan X, Matsuda Z, Matsuda M, Essex M, Lee T H. Human immunodeficiency virus vpr gene encodes a virion-associated protein. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:1265–1271. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]