Abstract

Background

Current evidence indicates that immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have a limited efficacy in patients with lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. However, there is a lack of data on the efficacy of ICIs after osimertinib treatment, and the predictors of ICI efficacy are unclear.

Methods

We retrospectively assessed consecutive patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who received ICI-based therapy after osimertinib treatment at 10 institutions in Japan, between March 2016 and March 2021. Immunohistochemical staining was used to evaluate the expression of p53 and AXL. The deletions of exon 19 and the exon 21 L858R point mutation in EGFR were defined as common mutations; other mutations were defined as uncommon mutations.

Results

A total of 36 patients with advanced or recurrent EGFR-mutant NSCLC were analyzed. In multivariate analysis, p53 expression in tumors was an independent predictor of PFS after ICI-based therapy (p = 0.002). In patients with common EGFR mutations, high AXL expression was a predictor of shorter PFS and overall survival after ICI-based therapy (log-rank test; p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively).

Conclusion

The levels of p53 in pretreatment tumors may be a predictor of ICI-based therapy outcomes in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC after osimertinib treatment. High levels of AXL in tumors may also be a predictor of ICI-based therapy outcomes, specifically for patients with common EGFR mutations. Further prospective large-scale investigations on the predictors of ICI efficacy following osimertinib treatment are warranted.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03370-1.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Non-small cell lung cancer, EGFR mutation, AXL, p53

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can improve long-term survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations [1–4]. Osimertinib is a third-generation EGFR-TKI that is highly effective and is widely used as a standard first-line treatment in NSCLC patients harboring EGFR mutations [4, 5]. In contrast, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have a limited efficacy in this patient group [6, 7]. Nevertheless, these results were based on treatment with first- and second-generation EGFR-TKIs. Therefore, there is a need for evidence of the efficacy of ICI-based regimen after osimertinib treatment. We previously evaluated the efficacy of an ICI-based treatment after osimertinib administration in a retrospective study [8].

In patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, several concomitant genetic mutations, including those in tumor protein p53 (TP53), AXL, RB transcriptional corepressor 1, phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha, and other driver oncogenes, were reported as predictive negative factors for initial EGFR-TKI administration [9–13]

TP53 mutations are the most frequent concomitant gene alternations in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, occurring in 55–65% of cases [9–11]. A previous study showed that patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC and concomitant TP53 mutations had shorter time to initial EGFR-TKI discontinuation compared to patients without TP53 mutations [14]. The positive correlation between p53 immunostaining and TP53 mutations has been reported for several carcinomas [15, 16].

AXL is a receptor tyrosine kinase belonging to the tumor-associated macrophage family [17]. High AXL levels have been associated with poor prognosis in several solid tumors [17–19]. Furthermore, our preclinical studies have shown that AXL activation plays a pivotal role in intrinsic resistance to EGFR-TKIs, including osimertinib, and leads to the emergence of osimertinib-tolerant cells among EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells [20, 21].

We previously reported on the negative impact of the expression of drug resistance-related proteins, p53 and AXL, in tumors on the efficacy of osimertinib in untreated patients with EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. Based on this study, we hypothesized that the expression of AXL and p53 in tumors might influence the efficacy of ICI-based therapy in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who had been treated with osimertinib [13]. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed the effects of the expression of p53 and AXL in pretreatment tumors on the efficacy of ICI-based therapy in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who had been treated with osimertinib.

Materials and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We assessed consecutive patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who received ICI-based therapy after osimertinib treatment, between March 2016 and March 2021. We performed an exploratory study to evaluate biomarkers for ICI-based therapy. The inclusion criteria were as follows: patient age ≥ 20 years; histologically confirmed NSCLC (classified based on response evaluation criteria in solid tumors [RECIST] version 1.1 criteria for measurable disease); confirmed EGFR-activating mutation (including one or more of the following: EGFR exon 19 deletion, S768I, L858R, L861Q, and G719X); and receipt of osimertinib treatment, anti-programmed death receptor-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)-based monotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy after osimertinib treatment. Patients were excluded if their residual specimens after pathological diagnosis could not be evaluated. Data pertaining to the following parameters at the start of ICI-based treatment were obtained from the medical records: age, sex, histological type, EGFR gene mutation status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), smoking history, tumor PD-L1 expression stained with the 22C3 antibody (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), progression-free survival (PFS) after ICI-based therapy, overall survival (OS), best overall response, and disease control rate. The eighth edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer staging system was used to assess staging. Tumor response was determined based on RECIST (version 1.1).

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, as well as by the Ethics Review Board of each hospital (approval no. ERB-C-1918). Because this was a retrospective study, the need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of each hospital; patients were given the opportunity to opt-out on the official study website.

Assessment of efficacy

PFS was defined as the time from the first administration of ICI-based therapy to disease progression or death. If the treatment was changed because of adverse events or other reasons before disease progression, the cutoff was the next treatment start date. OS was defined as the time from the first administration of ICI-based therapy to death.

Tumor genetic analysis

EGFR mutations were identified using either the Peptide Nucleic Acid Lock Nucleic Acid Clamp (LSI Medience, Tokyo, Japan), Cycleave Polymerase Chain Reaction (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), or Cobas EGFR Mutation Test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, Calif.). Sequencing of exons 18–21 was performed by a commercial clinical laboratory (SRL Corporation, BML, Tokyo, Japan). The deletions of exon 19 and the exon 21 L858R point mutation in EGFR were defined as common mutations, and any other mutations were defined as uncommon mutations.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and evaluation of p53 and AXL

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were cut into serial Sections 4–5 µm thick. Tissues were residual specimens at the time of diagnosis. The blocks were deparaffinized and immunostained with the following antibodies: p53 (clone DO7; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and Axl (goat polyclonal; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). We classified p53 expression as positive (nuclear staining of > 5% tumor cells) or negative (nuclear staining of < 5% tumor cells) [16]. As IHC staining varied in intensity, vascular endothelial cells were compared as internal controls and AXL expression was assessed as strong (3 +), intermediate (2 +), weak (1 +), or negative (0). Based on previous research, we categorized an AXL expression level of 3 + in tumors into the high AXL group and AXL expression levels of 2 + , 1 + , and 0 into the low AXL group [21] (Supplementary Fig. 1). Two pathologists (K–M. and S–T.) independently evaluated the expression of p53 and AXL and graded the staining intensity in accordance with previous reports [16, 21].

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. PFS and OS were censored upon final survival confirmation in patients whose disease did not progress and in those who survived. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze PFS and OS, and differences were compared using the log-rank test. In the univariate and multivariate analyses, Cox proportional hazard models were performed to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The analyses were performed using the EZR software, version 1.54 [22].

Results

Patient characteristics

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. A total of 36 patients (median age, 68 [range, 43–83] years, 21 [58.3%] males) from 10 institutions across Japan were included. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Nine (25.0%) patients had ECOG-PS 2/3, while postoperative recurrence was documented in 6 (16.7%) patients. Thirteen (36.1%) patients had a history of smoking, and 18 (50.0%) had undergone chemoimmunotherapy. The median follow-up time for censored cases was 18.4 months. A PD-L1 of ≥ 50% was more common in patients with positive p53 expression compared with that in those with negative p53 expression (p = 0.16) (Supplementary Table 1). With the exception of the PD-L1 tumor proportion score, there were no significant differences in background between patients with positive p53 expression and those with negative p53 expression (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, there were no significant differences in background between patients with a high AXL expression and those with a low AXL expression (Supplementary Table 2). Seventeen (47.2%) patients started a first subsequent therapy after the discontinuation of ICI-based therapy. The details of subsequent treatment after ICI-based therapy are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 36) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 68 (43–83) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 21 (58.3%) |

| Female | 15 (41.7%) |

| ECOG-PS | |

| 0 | 7 (19.4%) |

| 1 | 20 (55.6%) |

| 2/3 | 9 (25.0%) |

| Stage | |

| Postoperative recurrence | 6 (16.7%) |

| III/IV | 30 (83.3%) |

| EGFR mutation | |

| 19 deletion | 17 (47.2%) |

| L858R | 17 (47.2%) |

| G719X | 2 (5.6%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Current/former | 23 (63.9%) |

| Never | 13 (36.1%) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 36 (100%) |

| Regimen | |

| Chemoimmunotherapy | 18 (50.0%) |

| ICI monotherapy | 18 (50.0%) |

| Treatment line of osimertinib | |

| 1st line | 15 (41.7%) |

| 2nd line or later (T790M positive) | 21 (58.3%) |

| IHC for p53 | |

| Positive | 19 (52.8%) |

| Negative | 17 (47.2%) |

| IHC for AXL | |

| 3 + | 7 (19.4%) |

| 2 + | 14 (38.9%) |

| 1 + | 13 (36.1%) |

| 0 | 2 (5.6%) |

| PD-L1 TPS | |

| ≥ 50% | 12 (33.3%) |

| 1–49% | 12 (33.3%) |

| < 1% | 9 (25.0%) |

| Unknown | 3 (8.3%) |

| Angiogenesis inhibitor | |

| With bevacizumab | 15 (41.7%) |

| Without bevacizumab | 21 (58.3%) |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PD-L1 TPS, programmed death-ligand 1 tumor proportion score; PFS, progression-free survival

Evaluation of p53 and AXL expression in EGFR-mutated NSCLC tumors

Positive p53 expression was observed in 19 (52.8%) patients, and negative expression was observed in 17 (47.2%) patients. Strong (3 +), intermediate (2 +), weak (1 +), and negative (0) tumor AXL expression was found in 7 (19.4%), 14 (38.9%), 13 (36.1%), and 2 (5.6%) patients, respectively. Tumors with an AXL expression of 3 + were categorized into the high AXL group (19.4%), and those with an AXL expression of 2 + , 1 + , or 0 were categorized into the low AXL group (80.6%) (Table 1).

Treatment efficacy of an ICI-based regimen in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer

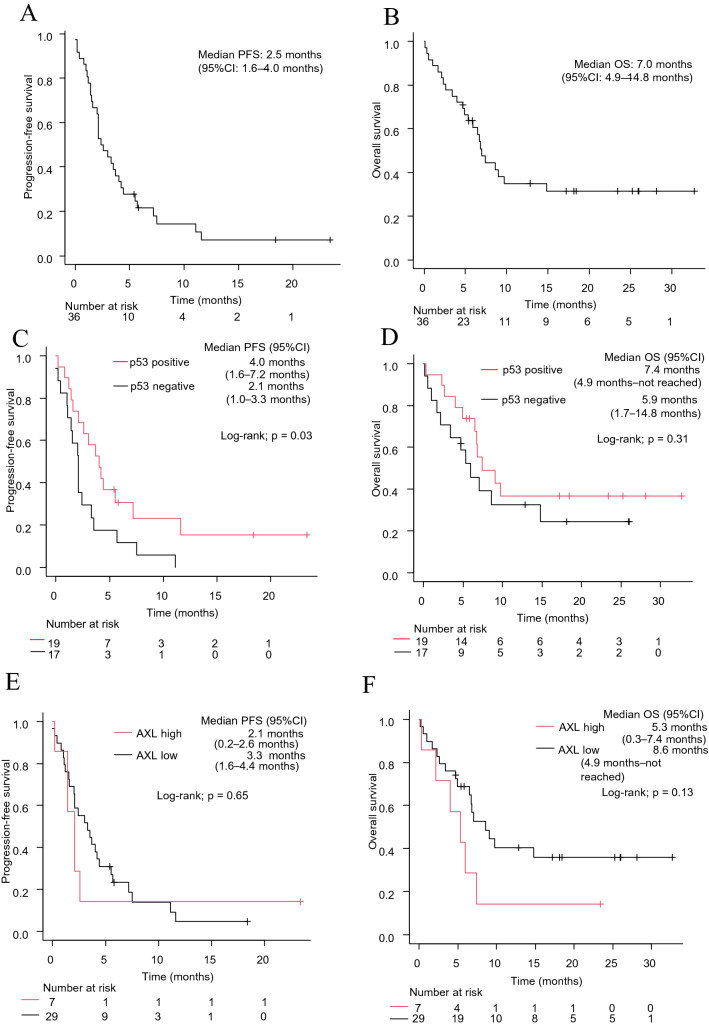

The objective response rate (ORR) of patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer who underwent ICI-based therapy was 16.7% (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The median PFS for ICI-based therapy was 2.5 months (95% CI: 1.6–4.0 months) (Fig. 1A). The median OS after ICI-based therapy was 7.0 months (95% CI: 4.9–14.8 months) (Fig. 1B). Patients with positive p53 expression had a higher ORR than those with negative p53 expression, although this did not reach statistical significance (26.3% versus 5.9%, p = 0.18) (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). There was no significant difference in ORR between the high and low AXL groups (14.3% versus 17.2%, p = 1.0) (Supplementary Fig. 3D, E).

Fig. 1.

PFS (A) and OS (B) of ICI-based therapy in all patients (n = 36). PFS (C) and OS (D) of ICI-based therapy according to p53 expression. PFS (E) and OS (F) of ICI-based therapy according to AXL expression. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

The median PFS was significantly longer for patients with positive p53 expression than for those with negative p53 expression (4.0 vs. 2.1 months, log-rank test p = 0.03) (Fig. 1C). The median OS after ICI-based therapy was not significantly affected by p53 levels in tumors (7.4 vs. 5.9 months, log-rank test p = 0.31) (Fig. 1D). There were no significant differences in PFS or OS according to the AXL levels in tumors (2.1 vs. 3.3 months, log-rank test p = 0.65; and 5.3 vs. 8.6 months, log-rank test p = 0.13, respectively) (Fig. 1E, F).

Association between clinicopathological factors and an ICI-based treatment regimen

In order to characterize patients who benefited from ICI-based therapy, we next examined the association between clinicopathological factors and PFS after ICI-based regimens. In univariate analysis, ECOG-PS, regimen, and p53 expression in tumors were predictors of PFS after ICI-based therapy (p = 0.0001, p = 0.003, and p = 0.04, respectively) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that ECOG-PS, regimen (chemoimmunotherapy), and p53 expression in tumors were independent predictive factors for PFS after ICI-based therapy (HR: 6.49, 95% CI: 2.26–18.6, p = 0.0005; HR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.17–0.90, p = 0.03; and HR 0.27, 95% CI: 0.12–0.61, p = 0.002, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate Cox proportional hazard models for PFS in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations who received ICI-based therapy

| Items | Patient no | Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median PFS (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Age | |||

| < 70 | 18 | 2.5 (1.0–4.2) | 0.77 |

| ≥ 70 | 18 | 2.6 (1.5–4.4) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 21 | 2.6 (1.1–4.2) | 0.92 |

| Female | 15 | 2.4 (1.5–4.4) | |

| ECOG-PS | |||

| 0/1 | 27 | 3.7 (2.1–5.7) | 0.0001 |

| ≥ 2 | 9 | 1.1 (0–2.6) | |

| Stage | |||

| Postoperative recurrence | 6 | 4.7 (1.2–NA) | 0.27 |

| III/IV | 30 | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | |

| EGFR mutation | |||

| Common mutation | 34 | 2.3 (1.5–3.7) | 0.15 |

| Uncommon mutation | 2 | 5.5 (5.5–NA) | |

| Smoking history | |||

| Current/former | 13 | 2.4 (0.4–3.7) | 0.46 |

| Never | 23 | 2.6 (1.6–5.5) | |

| Regimen | |||

| Chemoimmunotherapy | 18 | 4.9 (2.4–7.5) | 0.003 |

| ICI monotherapy | 18 | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | |

| PD-L1 expression | |||

| ≥ 50% | 12 | 3.2 (0.2–7.5) | 0.51 |

| < 50% | 21 | 2.1 (1.4–4.0) | |

| p53 expression | |||

| Positive | 19 | 4.0 (1.6–7.2) | 0.04 |

| Negative | 17 | 2.1 (1.0–3.3) | |

| AXL expression | |||

| High | 7 | 2.1 (0.2–2.6) | 0.65 |

| Low | 29 | 3.3 (1.6–4.4) | |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD-L1 TPS, programmed death-ligand 1 tumor proportion score; PFS, progression-free survival; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models for PFS in patients with non-small cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutations who received ICI-based therapy

| Items | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| ECOG-PS ≥ 2 (versus ECOG-PS 0 or 1) | 6.49 (2.26–18.6) | 0.0005 |

| Chemoimmunotherapy (vs. ICI monotherapy) | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | 0.03 |

| p53-positive (vs. p53-negative) | 0.27 (0.12–0.61) | 0.002 |

ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-performance status; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival

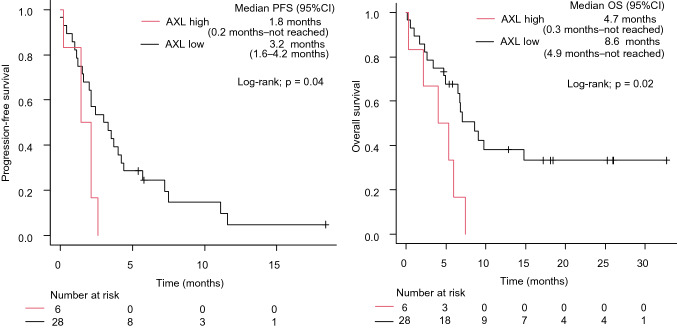

Impact of AXL expression on PFS and OS after ICI-based therapy in patients with common EGFR mutations

We previously indicated that among NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations, those with uncommon EGFR mutations were positively associated with the clinical benefits of ICI treatment [23]. Considering the possibility that uncommon mutations might have affected the analysis of ICI treatment efficacy, we further analyzed 34 patients with common mutations. The median PFS and OS were significantly shorter in patients with high AXL expression than in those with low AXL expression (1.8 vs. 3.2 months, log-rank test p = 0.04; and 4.7 vs. 8.6 months, log-rank test p = 0.02, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PFS (A) and OS (B) of ICI-based therapy according to AXL expression in NSCLC patients with EGFR common mutation. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Discussion

EGFR-TKIs have been shown to significantly improve survival in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC [5]. Various clinical studies have aimed to increase the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies to improve clinical outcomes in cases of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs. As ICI-based treatment has emerged as a promising therapy for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC, there is a need for the development of predictive biomarkers to facilitate selection of responders to ICI-based therapy. To date, few studies have evaluated potential predictors of osimertinib resistance, which is the current standard treatment.

The results of our retrospective study indicated that p53 expression in tumors may be a promising predictor of PFS after ICI-based therapy in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC who have been treated with osimertinib. In EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients with concomitant TP53 mutations, initial EGFR-TKI monotherapy was less effective [10, 14]. TP53 mutations have been reported as poor prognostic factors in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy [24]. On the contrary, TP53 mutations are positively correlated with the efficacy of ICIs in patients with NSCLC, regardless of the presence of driver oncogenes [25–27]. These previous reports and our study suggest that TP53 mutations might be specific markers for ICI-based therapy, but not for cytotoxic chemotherapy, in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients. Our results are also supported by previous findings that TP53 mutations significantly increase PD-L1 expression and activate effector T cell and interferon-γ signaling [25]. EGFR-TKI has also been shown to increase PD-L1 levels in tumor cells [28]. Therefore, in addition to TP53 status, an increased PD-L1 expression after osimertinib treatment may facilitate the effect of ICI-based therapy for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

In this study, we were unable to investigate the status of TP53 mutations and other concomitant mutations. Previous reports have demonstrated that immunostaining for intranuclear p53 is positively associated with TP53 mutations in several tumors [14, 15, 29]. Therefore, immunostaining for p53, as opposed to assessing the status of TP53 mutation, may be more useful for predicting the effect of ICI-based therapy after osimertinib treatment. This remains to be confirmed in additional clinical studies.

Our results show that patients with NSCLC harboring common EGFR mutations and a high level of AXL had significantly shorter PFS and OS after ICI-based therapy compared to those with a low level of AXL. AXL is involved in immunosuppressive mechanisms, such as decreased tumor antigen presentation, suppression of inflammatory cytokines, and inhibition of immune infiltration [30]. While we also observed that ICI-based therapy was relatively effective for patients with low AXL expression, this did not reach statistical significance. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that targeting AXL may mediate cancer cell sensitization to immune cell-mediated attack, reduce immunosuppression within the tumor immune microenvironment, and provide beneficial additive or synergistic effects when combined with ICIs [31–33]. Numerous ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of AXL inhibitors in combination with ICIs [30]. Currently available evidence suggests that a combination therapy with AXL inhibitors and ICIs may be a promising treatment option following osimertinib administration in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC and a high AXL level.

Our study had some limitations. First, the sample size was small. Second, since we only analyzed cases with residual specimens after pathological diagnosis, there may have been selection bias. Third, a broad range of factors may affect clinical outcomes following ICI-based therapy; however, not all of them could be adjusted for.

In conclusion, tumor protein-based analysis showed that p53 levels may be a predictive factor for clinical outcomes after ICI-based therapy in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Furthermore, AXL levels in tumors may be a predictor of ICI-based therapy outcomes, specifically for patients with common EGFR mutations. Further prospective large-scale investigations are warranted to confirm the effects of the expression of tumor p53 and AXL on clinical outcomes after ICI-based therapy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate the contributions of all the physicians and patients who participated in this study.

Author contributions

TY contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and supervision. KM was involved in methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, project administration, data curation. RS contributed to methodology. KA, YG, TH, SS, NT, YC, TT, OH, IH, and ST were involved in Investigation. KT contributed to writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision. AY, YHK, MI and ST was involved in project administration and data curation.

Funding

This research was conducted without any funding.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because of ethical constraints but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

TY received grants from Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical and personal fees from Eli Lilly. KA received personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology, and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. KT received grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical and Ono Pharmaceutical and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo. The other authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each hospital, including the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (Approval no. ERB-C-1918).

Consent to participate

Because this was a retrospective study, the need for informed consent was waived, and an official website was used as an opt-out method.

Consent to publish

Not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passaro A, Leighl N, Blackhall F, et al. ESMO expert consensus statements on the management of EGFR mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022;S0923–7534:00112. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazieres J, Drilon A, Lusque A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1321–1328. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto K, Sawada R, Yamada T, et al. A real-world analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapy after osimertinib treatment in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer patients. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3(9):100388. doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong S, Gao F, Fu S, et al. Concomitant genetic alterations with response to treatment and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):739–742. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim Y, Lee B, Shim JH, et al. Concurrent genetic alterations predict the progression to target therapy in EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.10.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nahar R, Zhai W, Zhang T, et al. Elucidating the genomic architecture of Asian EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma through multi-region exome sequencing. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):216. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02584-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Y, Song J, Wang Y, et al. Concurrent genetic alterations and other biomarkers predict treatment efficacy of EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: a review. Front Oncol. 2020;10:610923. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.610923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura A, Yamada T, Serizawa M et al (2022) High levels of AXL expression in untreated EGFR-mutated NSCLC negatively impacts the use of osimertinib. Cancer Sci. 10.1111/cas.15608. 10.1111/cas.15608. [published online ahead of print, 2022 Sep 28]

- 14.Offin M, Chan JM, Tenet M, et al. Concurrent RB1 and TP53 alterations define a subset of EGFR-mutant lung cancers at risk for histologic transformation and inferior clinical outcomes. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1784–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh N, Piskorz AM, Bosse T, et al. p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate surrogate for TP53 mutational analysis in endometrial carcinoma biopsies. J Pathol. 2020;250(3):336–345. doi: 10.1002/path.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang HJ, Nam SK, Park H, et al. Prediction of TP53 mutations by p53 immunohistochemistry and their prognostic significance in gastric cancer. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54(5):378–386. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2020.06.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antony J, Huang RY. AXL-driven EMT state as a targetable conduit in cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(14):3725–3732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham DK, DeRyckere D, Davies KD, Earp HS. The TAM family: phosphatidylserine sensing receptor tyrosine kinases gone awry in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(12):769–785. doi: 10.1038/nrc3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland SJ, Powell MJ, Franci C, et al. Multiple roles for the receptor tyrosine kinase axl in tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9294–9303. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okura N, Nishioka N, Yamada T, et al. ONO-7475, a novel AXL inhibitor, suppresses the adaptive resistance to initial EGFR-TKI treatment in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(9):2244–2256. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi H, Yamada T, Wang R, et al. AXL confers intrinsic resistance to osimertinib and advances the emergence of tolerant cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):259. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08074-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada T, Hirai S, Katayama Y, et al. Retrospective efficacy analysis of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8(4):1521–1529. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin S, Li X, Lin M, Yue W. Meta-analysis of P53 expression and sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine. 2021;100(5):e24194. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong ZY, Zhong WZ, Zhang XC, et al. Potential predictive value of TP53 and KRAS mutation status for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(12):3012–3024. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assoun S, Theou-Anton N, Nguenang M, et al. Association of TP53 mutations with response and longer survival under immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2019;132:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biton J, Mansuet-Lupo A, Pécuchet N, et al. TP53, STK11, and EGFR mutations predict tumor immune profile and the response to anti-PD-1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(22):5710–5723. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isomoto K, Haratani K, Hayashi H, et al. Impact of EGFR-TKI treatment on the tumor immune microenvironment in EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(8):2037–2046. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Köbel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2(4):247–258. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engelsen AST, Lotsberg ML, AbouKhouzam R, et al. Dissecting the role of AXL in cancer immune escape and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibition. Front Immunol. 2022;13:869676. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.869676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee W, Kim DK, Synn CB, et al. Incorporation of SKI-G-801, a novel AXL inhibitor, with anti-PD-1 plus chemotherapy improves anti-tumor activity and survival by enhancing T cell immunity. Front Oncol. 2022;12:821391. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.821391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Synn CB, Kim SE, Lee HK, et al. SKI-G-801, an AXL kinase inhibitor, blocks metastasis through inducing anti-tumor immune responses and potentiates anti-PD-1 therapy in mouse cancer models. Clin Transl Immunol. 2021;11(1):e1364. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goyette MA, Elkholi IE, Apcher C, et al. Targeting Axl favors an antitumorigenic microenvironment that enhances immunotherapy responses by decreasing Hif-1α levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(29):e2023868118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023868118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because of ethical constraints but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.