Abstract

Objectives

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) monotherapy was standard of care in second-line treatment of patients with advance non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study aims to investigate the efficacy of ICI plus chemotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

An investigator-initiated trial (IIT) aiming to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ICI in combination with chemotherapy as second line and beyond for patients with advanced NSCLC was undergone at Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (ChiCTR1900026203). Patients who received ICI monotherapy as second or later line setting during the same period were also collected as a comparator.

Results

From April 2018 to June 2019, 31 patients were included into this IIT study, simultaneously 51 patients treated with ICI monotherapy were selected as a comparator. ICI plus chemotherapy showed a significantly higher ORR (35.5% vs. 15.7%, p=0.039), prolonged PFS (median: 5.6 vs. 2.5 months, p = 0.013) and OS (median: NE vs. 12.6 months, p = 0.038) compared with ICI alone. In the subgroup of negative PD-L1 expression (9 patients in combination group and 12 patients in monotherapy group), ICI plus chemotherapy also had a favorable ORR (44.4% vs. 8.3%, p = 0.119), longer PFS (median: 6.5 vs 3.0 months, p < 0.05) and OS (median: NE vs. 8.2 months, p = 0.117). Meanwhile, the addition of chemotherapy did not increase immune-related adverse events.

Conclusions

ICI plus chemotherapy showed superior ORR, PFS and OS than ICI alone patients with previous treated advanced NSCLC. These findings warrant further investigation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-021-02974-9.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Chemotherapy, Combination, NSCLC, Second-line treatment

Introduction

Immunotherapy changed the paradigm for cancer treatment. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors such as pembrolizumab [1], nivolumab [2, 3], atezolizumab [4] demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), quality of life (QoL) and a favorable safety profile compared with standard chemotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC. However, the response rate of ICI monotherapy is around 20%, which limited its wider clinical application [5–8].

Series of studies have investigated the optimal biomarker of immunotherapy including PD-L1 status, tumor mutation burden (TMB) [9, 10], tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [11, 12] and effector T-cell (Teff) gene signature [13]. Currently, ICI monotherapy in front-line setting is only approved in patients with positive PD-L1 expression, especially in those with tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥ 50% or high tumor cells/tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TC/IC) expression [7, 14]. The other strategy to broaden the application and maximize the efficacy of immunotherapy is through combination. KEYNOTE189 [15] and CAMEL [16] trial proved that pembrolizumab or camrelizumab plus chemotherapy prolonged OS and PFS including population in first-line setting.

Similarly, in second-line setting, a recent PROLUNG study suggested that pembrolizumab plus docetaxel showed improved efficacy than docetaxel in patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy irrespective PD-L1 status [17], which raise the necessity to determine the recommendation level of ICI plus chemotherapy versus ICI monotherapy in this setting. Therefore, we underwent a prospective trial to assess the efficacy and safety of combination of ICI plus chemotherapy as second or later line regimens for patients with advanced NSCLC (ChiCTR1900026203). We further collected patients who received ICI monotherapy for second or later line therapy during the same period as the comparator to compare their efficacy and safety.

Patients and methods

Study design

An investigator-initiated trial prospectively evaluated the efficacy and safety of PD-1/PD-L1 antibody combined with chemotherapy as second line and beyond for patients with advanced NSCLC in Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (ChiCTR1900026203). This study included patients (a) aged < 80 years, (b) with an Eastern Corporation Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1, (c) histologically or cytologically confirmed unresectable stage III or IV NSCLC, (d) progressive disease after at least one prior chemotherapy, (e) under immunotherapy-naïve status, (e) have at least one measurable lesion per response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST, version 1.1). The primary endpoint of the study was investigator-assessed objective response rate (ORR) per RECIST 1.1, secondary endpoints included progression-free survival, disease control rate (DCR) and adverse events. Patients received anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy as second or later line during the same period (from April 2018 to June 2019) were also collected as a comparator. Detailed clinicopathologic characteristics including gender, age, smoking history, ECOG PS, histology, metastatic sites, oncogenic mutation status, regimens used in any line were extracted and collected. The results of tumor PD-L1 immunohistochemical (IHC) staining which evaluated by 22C3 pharmDx were also reviewed and TPS ≥ 1% were defined as positive PD-L1 expression[18]. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine (K18-200Y).

Evaluation of therapeutic outcomes

Tumor assessments were performed every 6 weeks (± 1 week). Imaging review of this study was assessed by investigators, two experienced oncologists (S.M. and F.Z.) independently evaluated all of the imaging data, and any inconsistencies were resolved by a third senior investigator (G.G.). Objective tumor responses were determined by investigators per RECIST 1.1. PFS was defined as the time interval from the date of ICI treatment initiation to the date of disease progression or death of any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients without disease progression or death were censored. OS was defined as the time interval from the date of ICI treatment initiation to the date of death of any cause or last follow-up in surviving participants. Treatment-related adverse events were evaluated per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.0). Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) which defined as the adverse events that have an immunological basis were identified by two investigators separately [19].

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess the distribution of the clinicopathological variables. PFS and OS curves were estimated by Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards model was performed, and hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to determine the survival difference. All of the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software (version 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, the USA). A significant difference was considered if the p value was less than 0.05 in two-sided analysis. Plots were generated by GraphPad Prism (version 7; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, the USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

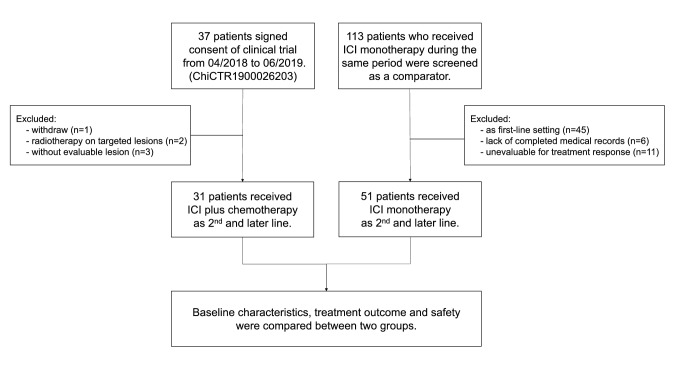

From April 2018 to June 2019, 37 patients have signed the consent of the clinical trial (study arm). Among them, one patient withdrawn before the treatment, two patients received radiotherapy on targeted lesions and three patients without evaluable lesion were excluded from the study. Meanwhile, 113 patients with advanced NSCLC who received ICI monotherapy were also screened as a comparator (control arm). Among them, 45 patients were treated as first-line, 6 patients lack completed medical records, and 11 patients without evaluable lesion for treatment response were excluded. Finally, 31 patients in the study arm and 51 patients in the control arm were included for further analysis (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. All of the included patients did not harbor epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusions. Their median age was 63 years old (range 29–77); 69 (84.1%) patients were male; 81 (98.8%) were with ECOG PS of 0–1; 49 (59.8%) were former or current smoker; 62 (75.6%) were stage IV disease, and 56 (68.3%) were non-squamous histological diagnosis. Notably, 13 (15.9%) patients had KRAS mutation, and 12 (14.6%), 12 (14.6%) and 29 (35.4%) had brain, liver or bone metastasis at baseline, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study design

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of ICI-treated patients with or without chemotherapy

| Total (n = 82) |

ICI alone (n = 51) |

ICI + chemo (n = 31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, No (%) | ||||

| Male | 69 (84.1) | 41 (80.4) | 28 (90.3) | 0.352 |

| Female | 13 (15.9) | 10 (19.6) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Age, yr, No (%) | ||||

| <65 | 49 (59.8) | 28 (54.9) | 21 (67.7) | 0.250 |

| ≥65 | 33 (40.2) | 23 (45.1) | 10 (32.3) | |

| ECOG PS, No (%) | ||||

| 0-1 | 81 (98.8) | 50 (98.0) | 31 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| 2 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Smoking histology, No (%) | ||||

| Never smoker | 33 (40.2) | 19 (37.3) | 14 (45.2) | 0.479 |

| Ever smoker | 49 (59.8) | 32 (62.7) | 17 (54.8) | |

| TNM stage, No (%) | ||||

| III | 20 (24.4) | 14 (27.5) | 6 (19.4) | 0.408 |

| IV | 62 (75.6) | 37 (72.5) | 25 (80.6) | |

| Histology, No (%) | ||||

| Non-squamous | 56 (68.3) | 34 (66.7) | 22 (71.0) | 0.685 |

| Squamous | 26 (31.7) | 17 (33.3) | 9 (29.0) | |

| Metastatic sites, No (%) | ||||

| Brain | 12 (14.6) | 5 (9.8) | 7 (22.6) | 0.196 |

| Liver | 12 (14.6) | 6 (11.8) | 6 (19.4) | 0.356 |

| Bone | 29 (35.4) | 15 (29.4) | 14 (45.2) | 0.148 |

| Oncogenic mutation, No (%) | ||||

| KRAS | 13 (15.9) | 11 (21.6) | 2 (6.5) | 0.117 |

| None | 69 (84.1) | 40 (78.4) | 29 (93.5) | |

| Line of ICI setting, No (%) | ||||

| 2 | 55 (67.1) | 31 (60.8) | 24 (77.4) | 0.120 |

| ≥3 | 27 (32.9) | 20 (39.2) | 7 (22.6) | |

| First-line treatment, No (%) | ||||

| Platinum-based doublet | 72 (87.8) | 46 (88.5) | 26 (83.9) | 0.454 |

| Platinum-based doublet with bevacizumab | 9 (11.0) | 4 (7.7) | 5 (16.1) | |

| Single agent chemotherapy | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

ICI Immune checkpoint inhibitors, ECOG PS Eastern corporation oncology group performance status

No significant difference of first-line setting has been observed between two groups of patients (Table 1). Concerning chemo-regimens used in study arm of ICI plus chemotherapy, 14 (45.2%) patients received docetaxel, 9 (29.0%) received nab-paclitaxel, 6 (19.4%) received pemetrexed and 2 (6.5%) received gemcitabine. The choose of ICI was determined by physicians. Among them, 22 (43.1%) and 21 (67.5%) patients received pembrolizumab, 16 (31.4%) and 6 (19.4%) patients received nivolumab, 5 (9.8%) and 0 (0.0%) patients received atezolizumab and 8 (15.7%) and 4 (12.9%) patients received camrelizumab in group of ICI alone and chemo-combined, respectively. 31 (60.8%) and 24 (77.4%) patients received ICI-based therapies as second-line therapy, respectively. Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics of two groups were well balanced (Table 1).

Efficacy

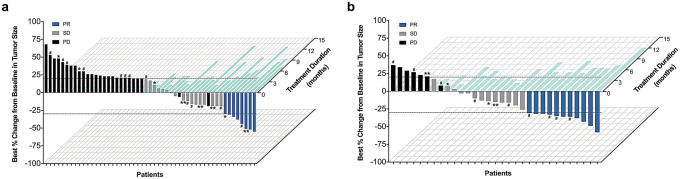

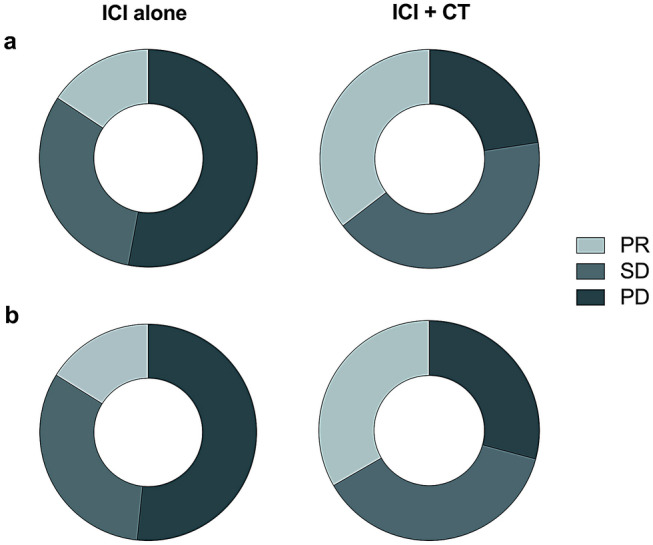

Responses to ICI-based treatments are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2. Among all patients received immunotherapy as second or later line setting, ICI plus chemotherapy showed statistically higher ORR and DCR than these received ICI alone (ORR: 35.5% vs. 15.7%, p = 0.039; DCR: 77.4% vs. 47.1%, p = 0.007) (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2a). When confined to second line (n = 55, Supplementary Table 2), the study arm also associated with numerically higher ORR and DCR (ORR: 33.3% vs. 16.1%, p = 0.136; DCR: 70.8% vs. 48.4%, p = 0.094) (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2b). Best percent changes from baseline in tumor size of both groups are presented as Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Radiologic response to ICI-based treatment. a treatment as second and later line setting, b treatment as second-line setting

Fig. 3.

Best percentage change in size of targeted lesions from baseline versus treatment duration in patients treated with a ICI monotherapy, b ICI plus chemotherapy. Patients (x-axis) were ordered by percentage change of targeted lesions from baseline (y-axis) and color-coded for best response per RECIST v1.1. Treatment duration (light blue) is shown on the z-axis. Patients who underwent PD-L1 IHC staining were marked as: *PD-L1 TPS 1–49%; **PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%; #PD-L1 TPS < 1%

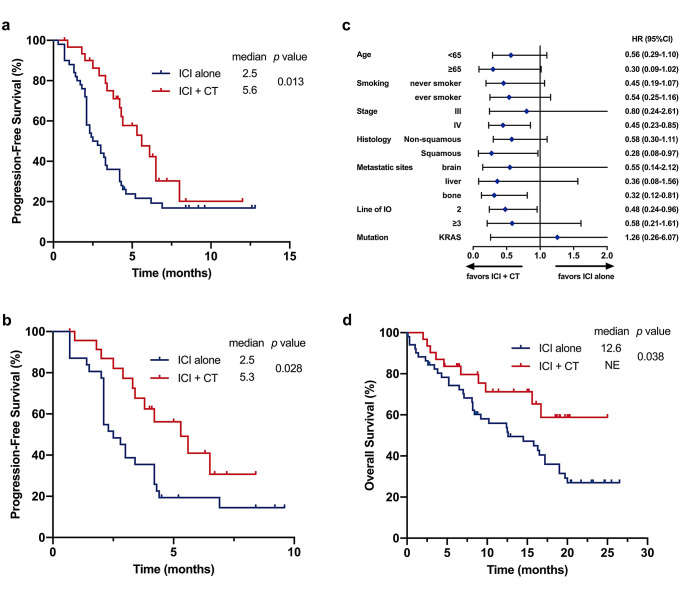

Median survival follow-up time was 11.9 months. Patients treated with ICI plus chemotherapy showed statistically superior PFS compared with patients treated with ICI alone (mPFS: 5.6 vs. 2.5 months, p = 0.013; HR=0.50, 95% CI: 0.28–0.88, p = 0.017) (Fig. 4a). When confined to second line, combination treatment also showed statistically longer PFS than ICI single agent (mPFS: 5.3 vs. 2.5 months, p = 0.028; HR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.24–0.96, p = 0.036) (Fig. 4b). The PFS of each patient is shown in Fig. 3 corresponding to their best percentage change in tumor size. Cox regression analysis, incorporating gender, age, smoking history, stage, histology, mutation, treatment line and treatment regimen, further identified ICI plus chemotherapy as independent prognostic factor of improved PFS compared with ICI alone (HR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.26–0.88, p = 0.017, Table 2). The impacts of ICI combined with or without chemotherapy on PFS within individual subgroups were further estimated. ICI plus chemotherapy showed superior PFS in all subgroups (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, combination treatment also showed statistically prolonged OS compared with monotherapy (mOS: NE vs. 12.6 months, p = 0.038; HR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.24–0.98, p = 0.043) (Fig. 4d), yet longer follow-up is needed since the data are still immature.

Fig. 4.

a Progression-free survival of patients treated with ICI-based regimens as second and later line setting, b Progression-free survival of patients treated with ICI-based regimens as second-line setting, c Forest plot of subgroup analysis by baseline characteristics for progression-free survival, d Overall survival of patients treated with ICI-based regimens as second and later line setting

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of clinical parameters on PFS

| Variable | Category | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Gender | Male vs. Female | 0.61 (0.30–1.20) | 0.151 | 0.80 (0.34–1.90) | 0.616 |

| Age | ≧65 y vs. <65y | 0.82 (0.48–1.41) | 0.472 | 0.79 (0.45–1.40) | 0.428 |

| Smoking history | Smoker vs. Never | 0.80 (0.47–1.34) | 0.389 | 0.82 (0.43–1.57) | 0.557 |

| Stage | III vs. IV | 1.00 (0.54–1.82) | 0.976 | 1.09 (0.56–2.15) | 0.797 |

| Histology | Non-SCC vs. SCC | 1.12 (0.64–1.97) | 0.698 | 1.09 (0.58–2.05) | 0.797 |

| Mutation | Kras vs. Wild Type | 1.17 (0.59–2.32) | 0.647 | 0.99 (0.46–2.16) | 0.987 |

| Treatment line | 2 vs. ≧3 | 1.08 (0.63–1.87) | 0.778 | 1.09 (0.62–1.92) | 0.762 |

| Treatment regimen | ICI + chemo vs. ICI alone | 0.50 (0.28–0.88) | 0.017 | 0.48 (0.26–0.88) | 0.017 |

ICI immune checkpoint inhibitors, PFS progression-free survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval SCC squamous-cell carcinoma

Treatment efficacy was further analyzed based on PD-L1 expression level which was dichotomized into two groups (positive and negative), using a cut-off value of 1%. Among 33 patients underwent tumor PD-L1 IHC staining, 12 (36.4%) patients were identified with positive PD-L1 expression, while 21 (63.6%) patients were negative, the distribution of treatment regimens use was well balanced (p = 0.719) (Supplementary Table 3). Clinical characteristics data between PD-L1 positive and negative patients in two groups of treatment are presented in supplementary Table 4. In the subgroup of patients with negative PD-L1 expression, combination of ICI with chemotherapy showed numerically superior response (ORR: 44.4% vs. 8.3%, p = 0.119; DCR: 66.7% vs. 41.7%, p = 0.387) (Supplementary Table 5) and survival (mPFS: 6.5 vs 3.0 months, p < 0.05, HR=0.15, 95% CI: 0.03–0.68, p < 0.05; mOS: NE vs. 8.2 months, p = 0.117, HR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.06–1.45, p = 0.138) (Supplementary Figure 1) compared with ICI monotherapy.

Adverse events

Adverse events of any cause occurred in 28 (54%) of the patients in the ICI alone group and 20 (65%) of the patients in the ICI plus chemotherapy group (Table 3). Events of grade 3 or higher were in 6 (12%) and 5 (16%) patients, respectively. No adverse events led to discontinuation or death occurred in both groups. The detailed incidences of adverse events are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of treatment emergent adverse events

| Patients, n (%) | ICI | ICI + chemo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |

| Any event | 28 (54) | 6 (12) | 20 (65) | 5 (16) |

| Rash | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 3 (6) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 2 (4) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Anemia | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Pneumonitis | 5 (10) | 2 (4) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) |

| ALT/AST increased | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Amylase increased | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cholesterol high | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

ICI immune checkpoint inhibitors

The most common adverse events of any grade were pneumonitis and increased alanine transaminase (ALT)/aspartate transaminase (AST) in ICI alone group, but leukopenia and neutropenia were more prevalent in ICI plus chemotherapy group. ICI plus chemotherapy showed increased incidence of hematological adverse events, including leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia and decreased appetite. No adverse events of grade 3 or higher that were reported in at least 5% of patients in any of these two groups. Notably, the incidence of immune-related adverse events was numerically lower in ICI plus chemotherapy group than ICI alone group. Most of the patients experienced mild irAEs as grade 1 or 2, and none of them discontinued treatments because of irAEs.

Discussion

In this study, we firstly compared the efficacy of ICI plus chemotherapy with ICI alone in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC and found that combination treatment showed a significantly increased ORR, prolonged PFS and OS. In the subgroup of patients with negative PD-L1 expression, ICI plus chemotherapy also had a favorable ORR, longer PFS and OS. Meanwhile, the addition of chemotherapy did not increase immune-related adverse events, suggesting ICI plus chemotherapy as later line setting should be recommended in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are the backbone for the systemic anti-cancer therapy in patients of advanced lung cancer without EGFR mutation or ALK fusion. Several immunotherapy regimens, such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy [20, 21], in combination with chemotherapy [15, 16, 22–24], in combination with chemotherapy and bevacizumab [13] or in combination with anti-CTLA4 [25] have been established as front-line regimens in NSCLC. Among them, a series of clinical trials have demonstrated that the combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy as first line improved responses and outcomes even in PD-L1 negative population. The synergistic effect of ICI and chemotherapy can be elucidated by increasing the antigenicity, triggering immunogenic cell death and modulating tumor microenvironment [26–29]. At the same time, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapies have also showed superior efficacy than chemotherapy in patients of advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 expression or higher expression [30, 31]. Currently, several studies such as SWOG1709 (NCT03793179) and PERSEE (NCT04547504) are ongoing to compared pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy with pembrolizumab alone in advanced NSCLC of positive PD-L1 expression to identify the preferred therapeutic strategy in this setting.

Similarly, in second-line setting, ICI monotherapy is the only current recommendation for patients with advanced NSCLC. Meanwhile, a recent phase 2 PROLUNG trial compared the combination of pembrolizumab and docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line setting in advanced NSCLC and found that the combination could improve ORR (ORR: 42.5% vs. 15.8%, p = 0.01) and PFS (median 9.5 vs. 3.9 months, p < 0.001) irrespective of PD-L1 status [17]. Moreover, a retrospective study found that PD-1 inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy and/or bevacizumab might be a favorable treatment option for NSCLC patients who had failed on the first line or later treatment, yet with a limited sample size [32]. Furthermore, our study found that ICI in combination with chemotherapy showed a higher ORR (p = 0.039) and significantly longer PFS (p = 0.013) even though when compared with ICI as the second or later line setting. More importantly, we firstly showed that the combination could also associate with a significantly longer OS (p = 0.038), further favoring the combining of ICI and chemotherapy in this setting.

Currently, PD-L1 expression is the only biomarker to guide ICI monotherapy treatment as first-line setting in clinical practice. Meanwhile, ICI monotherapy is recommended regardless PD-L1 expression level as in second or later line setting. In this study, we further performed a subgroup analysis according to PD-L1 expression. In patients with negative PD-L1 expression accounted for the majority (21/33, 63.6%), we still observed that the superior efficacy and outcome of ICI plus chemotherapy than ICI monotherapy. In addition, compared to previous studies, our study showed a higher proportion of negative PD-L1 expression population [33–36]. The reason might be that the majority of patients with positive PD-L1 expression received the front immunotherapy in clinical practice during the period of this study. Actually, IMpower150 study showed a similar efficacy between chemotherapy plus atezolizumab (arm A) and chemotherapy plus bevacizumab (arm C) in advanced non-squamous NSCLC with negative PD-L1 expression [37], suggesting that ICIs excluded first-line regimen are still a feasible option in this population. Besides PD-L1 negative expression, further study is warranted to identify other subpopulations that might favor this ICI combination regimen as second-line setting who choose immunotherapy-naïve treatment as first-line setting.

Safety analyses showed a higher incidence of treatment-related adverse events in ICI plus chemotherapy than in ICI alone (Any grade: 65% vs. 54%; Grade 3–4: 16% vs. 12%), which is similar to previous reports[17, 38]. Most of the increased grade 3–4 adverse events in the combination group were chemo-related hematological toxicities, including one leukopenia, one neutropenia and one thrombocytopenia, while immune-related adverse events such as pneumonitis and hypothyroidism did not increase. No treatment-related death occurred in both groups, suggesting the toxicity is acceptable in the combination group.

Several limitations must be acknowledged in the present study. Firstly, the control arm came from patients who received ICI monotherapy at the same period, thus selection bias will be inevitable. Secondly, the data of control arm were extracted from medical records, and therefore, AE reported in this study might be underestimated. Meanwhile, the efficacy evaluation scan of control arm might delay in the clinical practice and therefore might cause a prolonged PFS. However, these features further supported the superior efficacy and acceptable toxicity of the combination arm. Thirdly, four different PD-1/PD-L1 mono-antibodies were used in this study, which might affect the efficacy even though all of them showed a similar objective response rate in the second-line setting in patients with advanced NSCLC. Last but not least, the number of patients treated with immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy was limited. Further prospective, multi-center randomized controlled studies are warranted to verify the current findings.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that ICI plus chemotherapy showed superior ORR, PFS and OS than ICI alone together with acceptable safety profiles as second and later lines in patients with advanced NSCLC. Further, prospective randomized trial is needed to validate the findings in this study.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the participating patients and their families. Abstract of part of this study was presented in the 2019 World Conference on Lung Cancer, Barcelona, Spain.

Abbreviations

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- CI

Confidence interval

- CTCAE

Common terminology criteria for adverse events

- DCR

Disease control rate

- ECOG

Eastern cooperative oncology group

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IC

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells

- IHC

Immunohistochemical

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- irAEs

Immune-related adverse events

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- QoL

Quality of life

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death ligand 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PS

Performance status

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- TC

Tumor cells

- Teff

Effector T-cell

- TILs

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TMB

Tumor mutation burden

- TPS

Tumor proportion score

Authors' contributions

SR, GG, CZ designed this study and revised the manuscript. SM and FZ drafted the manuscript. SM, SY, BC, JX, FW, WW, XY and QL collected and assembled the data. SM, YL, XL, CZ, KJ and CS performed data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in manuscript writing. All authors gave the final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81772467 to S.R., No. 81972167 to S.R.), Shanghai Pujiang Program (No. 2019PJD048 to S.R.), Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (No. SHDC12019133 to S.R.), the Backbone Program of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital (NO. FKGG1802 to S.R.) and Shanghai Innovative Collaboration Project (No. 2020CXJQ02 to C. Z.).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine (K18-200Y). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shiqi Mao and Fei Zhou have contributed equally to this paper.

Contributor Information

Guanghui Gao, Email: ghgao103@hotmail.com.

Shengxiang Ren, Email: harry_ren@126.com.

Reference

- 1.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Pérez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, Hida T, Kowalski DM, Dols MC, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32517-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L, Eberhardt WEE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, Hida T, Kowalski DM, Dols MC. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, Creelan B, Horn L, Steins M, Felip E, van den Heuvel MM, Ciuleanu TE, Badin F, et al. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2415–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ock CY, Keam B, Kim S, Lee JS, Kim M, Kim TM, Jeon YK, Kim DW, Chung DH, Heo DS. Pan-cancer immunogenomic perspective on the tumor microenvironment based on PD-L1 and CD8 T-cell infiltration. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(9):2261–2270. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-15-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bremnes RM, Busund LT, Kilvær TL, Andersen S, Richardsen E, Paulsen EE, Hald S, Khanehkenari MR, Cooper WA, Kao SC, et al. The role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in development, progression, and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(6):789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Moro-Sibilot D, Thomas CA, Barlesi F, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, Molina J, Kim JH, Arvis CD, Ahn MJ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, Domine M, Clingan P, Hochmair MJ, Powell SF, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou C, Chen G, Huang Y, Zhou J, Lin L, Feng J, Wang Z, Shu Y, Shi J, Hu Y, et al. Camrelizumab plus carboplatin and pemetrexed versus chemotherapy alone in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CameL): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):305–314. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arrieta O, Barrón F, Ramírez-Tirado LA, Zatarain-Barrón ZL, Cardona AF, Díaz-García D, Yamamoto Ramos M, Mota-Vega B, Carmona A, Peralta Álvarez MP, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab plus docetaxel vs docetaxel alone in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The PROLUNG phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng TL, Liu Y, Dimou A, Patil T, Aisner DL, Dong Z, Jiang T, Su C, Wu C, Ren S, et al. Predictive value of oncogenic driver subtype, programmed death-1 ligand (PD-L1) score, and smoking status on the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in patients with oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(7):1038–1049. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, Berdelou A, Varga A, Bahleda R, Hollebecque A, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, Castro G, Jr, Srimuninnimit V, Laktionov KK, Bondarenko I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spigel D, De Marinis F, Giaccone G, Reinmuth N, Vergnenegre A, Barrios CH, Morise M, Felip E, Andric Z, Geater S. IMpower110: Interim overall survival (OS) analysis of a phase III study of atezolizumab (atezo) vs platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line (1L) treatment (tx) in PD-L1–selected NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v915. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Gümüş M, Mazières J, Hermes B, Çay Şenler F, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040–2051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, Morabito A, Rittmeyer A, Conter HJ, Kopp HG, Daniel D, McCune S, Mekhail T, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):924–937. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Wang Z, Fang J, Yu Q, Han B, Cang S, Chen G, Mei X, Yang Z, Ma R, et al. Efficacy and safety of sintilimab plus pemetrexed and platinum as first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study (Oncology pRogram by InnovENT anti-PD-1-11) J Thorac Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, Zurawski B, Kim S-W, Carcereny Costa E, Park K, Alexandru A, Lupinacci L, de la Mora Jimenez E. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beatty GL, Gladney WL. Immune escape mechanisms as a guide for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(4):687–692. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-14-1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galluzzi L, Buqué A, Kepp O, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(2):97–111. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(3):197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mok TSK, Wu Y-L, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, Castro G, Jr, Srimuninnimit V, Laktionov KK, Bondarenko I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang F, Huang D, Li T, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhang Y, Wang G, Zhao Z, Ma J, Wang L, et al. Anti-PD-1 therapy plus chemotherapy and/or bevacizumab as second line or later treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2020;11(3):741–749. doi: 10.7150/jca.37966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo L, Song P, Xue X, Guo C, Han L, Fang Q, Ying J, Gao S, Li W (2019) Variation of Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression After Platinum-based Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Lung Cancer. Journal of immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md : 1997) 42 (6):215-220. doi:10.1097/CJI.0000000000000275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Song Z, Yu X, Zhang Y. Altered expression of programmed death-ligand 1 after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2016;99:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rojkó L, Reiniger L, Téglási V, Fábián K, Pipek O, Vágvölgyi A, Agócs L, Fillinger J, Kajdácsi Z, Tímár J. Chemotherapy treatment is associated with altered PD-L1 expression in lung cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(7):1219–1226. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2642-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H, Boyle TA, Zhou C, Rimm DL, Hirsch FR. PD-L1 Expression in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(7):964–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reck M, Mok TSK, Nishio M, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Moro-Sibilot D, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(5):387–401. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu YL, Lu S, Cheng Y, Zhou C, Wang J, Mok T, Zhang L, Tu HY, Wu L, Feng J, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in a predominantly chinese patient population with previously treated advanced NSCLC: CheckMate 078 randomized phase III clinical Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(5):867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.