Abstract

Background

We evaluated MK-4621, an oligonucleotide that binds and activates retinoic acid–inducible gene I (RIG-I), as monotherapy (NCT03065023) and in combination with the anti–programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab (NCT03739138).

Patients and methods

Patients were ≥ 18 years with histologically/cytologically confirmed advanced/metastatic solid tumors with injectable lesions. MK-4621 (0.2‒0.8 mg) was administered intratumorally as a stable formulation with jetPEI™ twice weekly over a 4-week cycle as monotherapy and weekly in 3-week cycles for up to 6 cycles in combination with 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles. Primary endpoints were dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs), treatment-related adverse events (AEs), and treatment discontinuation due to AEs.

Results

Fifteen patients received MK-4621 monotherapy and 30 received MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab. The only DLT, grade 3 pleural effusion that subsequently resolved, occurred in a patient who received MK-4621/jetPEI™ 0.8 mg plus pembrolizumab. 93% of patients experienced ≥ 1 treatment-related AE with both monotherapy and combination therapy. No patients experienced an objective response per RECIST v1.1 with MK-4621 monotherapy; 4 (27%) had stable disease. Three (10%) patients who received combination therapy had a partial response. Serum and tumor biomarker analyses provided evidence that MK-4621 treatment induced an increase in gene expression of interferon signaling pathway members and associated chemokines and cytokines.

Conclusions

Patients treated with MK-4621 monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab experienced tolerable safety and modest antitumor activity, and there was evidence that MK-4621 activated the RIG-I pathway. At the doses tested, MK-4621 did not confer meaningful clinical benefit.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03065023 and NCT03739138.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-022-03191-8.

Keywords: RIG-I, Interferon type I, Innate immunity, Intratumoral injection, Pembrolizumab

Introduction

Development of immunotherapies, in particular immune checkpoint blockers targeting programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), has resulted in improved outcomes for patients with various solid tumors [1, 2]. Tumors that do not respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitors or become refractory often have characteristics of immunologically “cold” tumors; agents with capacity to reverse this state can be used to convert these tumors into “hot” tumors [3, 4].

A potential target for inducing an inflammatory response within the tumor microenvironment is retinoic acid–inducible gene I (RIG-I), a ubiquitously expressed cytosolic RNA receptor that recognizes a double-stranded RNA bearing 5′-triphosphate [5]. RIG-I plays a key role in antiviral defense, activating the innate immune system through type I interferon (IFN) signaling [5, 6]. There is clear evidence that type I IFN signaling plays a pivotal role in naturally occurring and therapy-induced anticancer response [7]. In addition, RIG-I has also been shown to induce apoptosis preferentially in tumor cells via an IFN-independent mechanism [8, 9]. MK-4621 is an oligonucleotide that selectively binds RIG-I to activate the RIG-I pathway [10]. MK-4621 is formulated with jetPEI™ (Polyplus Transfection, Illkirch, France), a linear polyethylenimine (PEI) derivative that promotes its delivery to the cytosol. Intratumoral injection of MK-4621 induced durable type I IFN response and potent antitumor activity in mouse models of melanoma and colon cancer [10].

Herein, we describe results from 2 early phase, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation studies that evaluated safety and preliminary efficacy of MK-4621 in patients with advanced solid tumors. The initial study was a first-in-human trial that evaluated MK-4621 as a monotherapy (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03065023); the second was a phase 1b study that evaluated MK-4621 in combination with the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03739138). In both studies, the primary objectives were to evaluate the safety and tolerability of MK-4621 (either as monotherapy or in combination with pembrolizumab) and to establish a dose for potential evaluation in future studies.

Methods

Patients

Eligibility criteria in the monotherapy and combination studies were similar. Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years, had histologically/cytologically confirmed advanced/metastatic solid tumors (patients with lymphoma [except those of NK cell origin] were permitted in the monotherapy study, but none were enrolled), had received or were intolerant to all treatments known to confer clinical benefit, had adequate organ function, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of ≤ 2 (monotherapy study) or ≤ 1 (combination study). Patients were required to have injectable lesions. In the monotherapy study, this was defined as cutaneous, subcutaneous, or lymph node injectable tumors with ≥ 1 lesion measurable by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1 and ≥ 1 separate injectable lesion with diameter ≥ 1 cm and ≤ 7 cm. In the combination study, patients were required to have ≥ 3 lesions: ≥ 1 cutaneous/subcutaneous lesion amenable to injection and biopsy that was measurable per RECIST v1.1 (non-nodal lesion ≥ 1 cm in the longest dimension, nodal lesion ≥ 1.5 cm in the short axis and ≤ 10 cm in the longest diameter); ≥ 1 discrete noninjected, non-biopsied lesion; and ≥ 1 discrete and/or distant, noninjected lesion amenable for biopsy. Exclusion criteria included recent anticancer therapy, adverse events (AEs) from prior therapy, active autoimmune disease requiring systemic treatment, and central nervous system metastases/carcinomatous meningitis. Full details are described in the respective protocols.

Procedures were approved by an institutional review/ethics committee at each site. Patients provided written informed consent.

Study design

The monotherapy study employed a standard 3 + 3 dose-escalation design, with MK-4621 dose levels of 0.2 mg, 0.4 mg, 0.6 mg, and 0.8 mg. MK-4621 was administered twice weekly over a 4-week period (1 cycle). Patients without overt clinical progression/intolerable toxicity could enter an extended treatment period at the same dose. A minimum of 3 patients were required at each dose. DLTs were defined as nonhematologic toxicity grade ≥ 3 (except diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting unless lasting > 3 days), confirmed nonhematologic laboratory findings of grade ≥ 3 that were grade ≤ 1 at baseline, grade 4 neutropenia lasting ≥ 5 days or grade 3 neutropenia with fever >38.4°C grade 4 thrombocytopenia or grade 3 thrombocytopenia lasting > 7 days, or any other toxicity assessed as related to MK-4621 and constituted a DLT per investigator/sponsor assessment. The DLT evaluation period was 1 cycle (4 weeks). The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was defined as 1 dose level below the dose at which ≥ 2 of 6 patients in a group experienced a DLT.

In the combination study, MK-4621 dose escalation followed a modified toxicity probability design with a target DLT rate of 30% [11], beginning at a dose of 0.4 mg, followed by 0.6 mg, then 0.8 mg. MK-4621 was administered weekly in 3-week cycles for up to 6 cycles. Pembrolizumab 200 mg was given by intravenous infusion every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles. A minimum of 3 patients were required at each dose level; if no patients experienced a DLT during cycle 1, dose escalation could proceed; if 1 patient experienced a DLT, then additional patients were enrolled. DLTs were defined as grade 4 nonhematologic toxicity, grade 4 hematologic toxicity lasting ≥ 7 days except thrombocytopenia (grade 4 or grade 3 associated with clinically significant bleeding), any nonhematologic AE of grade ≥ 3 in severity (except grade 3 fatigue lasting ≤ 3 days; grade 3 diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting without use of antiemetics or antidiarrheals per standard of care; grade 3 rash without use of corticosteroids or anti-inflammatory agents per standard of care; or grade 3 drug-related fever that resolves within 24 h), any grade 3/4 nonhematologic laboratory value if clinically significant medical intervention is required or the abnormality leads to hospitalization, persists for > 1 week, or results in drug-induced liver injury (except clinically nonsignificant, treatable, or reversible laboratory abnormalities), febrile neutropenia of grade 3 (absolute neutrophil count < 1000/mm3with a single temperature of > 38.3 °C or a sustained temperature of ≥ 38 °C for > 1 h) or 4 (grade 3 criteria plus life-threatening consequences and urgent intervention indicated), delay of > 2 weeks in initiating cycle 2 due to treatment-related oxicities, any treatment-related toxicity that causes the patient to discontinue treatment during cycle 1, or missing > 2 injections of MK-4621 due to drug-related AEs during the first cycle.

The primary endpoints of both studies were incidence of DLTs, incidence and severity of treatment-related AEs, and treatment discontinuation due to AEs. Evaluation of the objective response rate per immune-related RECIST (irRECIST) or by RECIST v1.1 by investigator assessment was a secondary endpoint in the monotherapy and combination studies, respectively [12, 13]. Assessment of MK-4621 pharmacokinetic parameters was an exploratory endpoint in the monotherapy study and a secondary endpoint in the combination study. Biomarker evaluation was a prespecified exploratory endpoint in both studies.

Intratumoral administration of MK-4621

MK-4621 was administered as a stable formulation with jetPEI™ once or twice weekly by intratumoral injection into cutaneous, subcutaneous, and/or nodal lesions that were visible, palpable, or detectable by ultrasound guidance. Dose levels were based on results from preclinical studies in mice and cynomolgus monkeys extrapolated for use in human tumors. The total volume of MK-4621 administered was determined by the dose level (1 mL at the 0.2-mg dose level, increasing to 4 mL at the 0.8-mg dose level). The maximum MK-4621 injection volume was administered to a single sufficiently sized target lesion at treatment initiation (≥ 1 cm for 1 mL, ≥ 2 cm for 2 mL, ≥ 3 cm for 3 mL, and ≥ 4 cm for 4 mL). Splitting the dose across additional lesions was permissible in subsequent treatments if the original lesion became non-amenable for injection; any new or progressing lesions were prioritized for injection.

Assessments

Adverse events were assessed from the time of initiation of study treatment until 30 days after the last dose of study treatment (90 days for serious AEs in the combination study). All toxicities were recorded and graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) v4.0 by the investigator. Radiographic imaging by computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography was done at baseline and every 8 weeks (monotherapy study) or 9 weeks (combination study) thereafter. Response was assessed by the investigator per irRECIST (monotherapy study) or per RECIST v1.1, with a modification to allow a maximum of 10 target lesions and 5 per organ (combination study) [12, 13].

Biopsies (punch, core needle, or excision) were taken at baseline from lesions chosen for injection and 1 lesion not chosen for injection, if possible. If the lesion intended for injection could not be biopsied, the next adjacent lesion was used. Biopsies were also obtained on week 5, day 29 (after completion of the first cycle in the monotherapy study) and on cycle 3, day 1 in the combination study. A selection of biomarkers was assessed based on preclinical data that demonstrated RIG-I activation drives increases in type I IFN pathways. Biomarkers were analyzed from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue collected at baseline (i.e., before injection). These included IFN-induced proteins with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1) [14, 15] expression levels from tumor tissue mRNA using Nanostring (Nanostring, Seattle, WA) for both studies, collected at times listed above. For the combination study, tumor PD-L1 expression levels were evaluated from baseline biopsies using PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Tumor mutational burden (TMB) was analyzed using DNA extracted from FFPE tissue and evaluated using TruSight Oncology 500 Local App version 1 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Manufacturer’s quality control criteria were used to determine if a TruSight Oncology 500 TMB result was valid. Finally, T cell-inflamed gene expression profile (TcellinfGEP) analysis was derived from the Nanostring PanCancer Immune Panel, which contains 17/18 target and 5/10 housekeeping genes present in the TcellinfGEP previously described by Ayers et al. [16]. TcellinfGEP scores were calculated as a weighted sum of normalized expression values for the 17 genes.

Two additional biomarkers involved in innate immune response, C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) [17] and C–C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CCL8) [18], were measured before administration of MK-4621 and at 6 and 24 h after administration in the monotherapy study, and before and 2, 6, and 24 h after administration of MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab from patient serum using immunoassays in the combination study.

Statistical analysis

Patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study medication were included in the as-treated population for both safety and efficacy analysis. Clinical data, plasma concentrations, and biomarker data were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patients

Fifteen patients were enrolled in the MK-4621 monotherapy study, and 30 patients were enrolled in the MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab combination study; patients were enrolled in the monotherapy study from April 25, 2017, to March 22, 2018, and in the combination study from January 10, 2019, to March 10, 2020. Baseline characteristics were similar across both studies (Table 1). In the monotherapy study, melanoma was the most common tumor type; in the combination study, breast cancer and melanoma were the most common (Table 1). All patients in the monotherapy study had ≥ 1 prior line of therapy; in 11 patients, the prior lines of treatment included ≥ 1 immune checkpoint inhibitor. In the combination study, 90% of patients had received ≥ 2 prior lines of therapy; in 9 patients, the prior lines of treatment included ≥ 1 immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | MK-4621 monotherapy | MK-4621 + pembrolizumab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK-4621 0.2 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg n = 6 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg + Pembro n = 7 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg + Pembro n = 5 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg + Pembro n = 18 |

|

| Age, median (range), y |

59.0 (22–74) |

46.0 (32–68) |

56.0 (39–71) |

61.0 (55–78) |

59.0 (40–69) |

63.0 (44–78) |

56.5 (46–76) |

| Men | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 4 (67) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 10 (56) |

| ECOG performance status score 1 | 2 (67) | 0 | 1 (33) | 6 (100) | 4 (57) | 5 (100) | 11 (61) |

| Tumor type | |||||||

| Breast cancer | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (43) | 0 | 3 (17) |

| Melanoma | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 3 (50) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 3 (17) |

| Colorectal cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 2 (11) |

| Ovarian cancer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (40) | 1 (6) |

| Leiomyosarcomaa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11) |

| Uterine/endometrial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Otherb | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 2 (33) | 2 (29) | 2 (40) | 7 (39) |

| Prior lines of therapy | |||||||

| Not availablec | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33) | 0 | 0 | 2 (11) |

| 2 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 5 (28) |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 3 (43) | 1 (20) | 2 (11) |

| 4 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 2 (33) | 0 | 2 (40) | 4 (22) |

| ≥ 5 | 1 (33) | 0 | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 5 (28) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless specified otherwise

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

aExcluding uterine leiomyosarcoma

bNo specific tumor type with > 1 patient. Tumor types: adenoid-cystic carcinoma, cervical cancer, esophageal, head and neck, kidney, lung, pleomorphic sarcoma, small-cell lung cancer, thymoma, soft tissue sarcoma, parotid gland, and cancer of unknown primary (most likely in the head and neck area)

cData on number of prior therapies is not available

In the monotherapy study, as of the data cutoff date (August 30, 2018), 15 patients were evaluated for safety and efficacy; 11 patients (73.3%) completed study treatment (i.e., one 4-week cycle), with 6 entering the extended-treatment phase beyond cycle 1. Four patients (26.7%) discontinued study treatment (disease progression, n = 2; investigator/patient decision, n = 2). Of 30 patients evaluated in the combination study (in which patients received up to 6 cycles of MK-4621 and 35 cycles of pembrolizumab), 26 (86.7%) had discontinued study treatment (disease progression, n = 22; adverse event, n = 2; noncompliance, n = 1; patient withdrawal, n = 1); 4 patients (13.3%) were ongoing as of the data cutoff date of May 14, 2020. Among patients in the monotherapy study, median (range) time on therapy was 25 (22−102) days and 57 (1–365) days in the combination study (Supplementary Table 1).

Safety

The only DLT in either study occurred in a patient with breast cancer with metastatic disease in the thorax who received 0.8 mg of MK-4621/jetPEI™ plus pembrolizumab. The DLT was a grade 3 pleural effusion that was assessed by the investigator as treatment-related and subsequently resolved. No other DLTs were observed, and the MTD was not reached in either study.

Fourteen patients (93%) treated with MK-4621 monotherapy experienced ≥ 1 treatment-related AE, most frequently pyrexia (73%), fatigue (40%), chills (27%), headache (27%), and nausea (27%; Table 2). Only 2 of these treatment-related AEs were grade 3: pyrexia and pain (n = 1; 7%). There were no treatment-related grade 4/5 AEs. One patient in the 0.2-mg treatment group died of respiratory failure that was not related to study treatment.

Table 2.

Treatment-related adverse events

| MK-4621 monotherapy | MK-4621 + pembrolizumab | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK-4621 0.2 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg n = 6 |

All Patients N = 15 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg + Pembro n = 7 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg + Pembro n = 5 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg + Pembro n = 18 |

All Patients N = 30 |

|

| Treatment-related AEs | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) | 14 (93) | 6 (86) | 5 (100) | 17 (94) | 28 (93) |

| Grade 3a | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 2 (13) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 5 (28) | 7 (23) |

| Led to discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Treatment-related AEs occurring in ≥ 10% of patientsb | |||||||||

| Pyrexia | 0 | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 5 (83) | 11 (73) | 5 (71) | 4 (80) | 10 (56) | 19 (63) |

| Chills | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 3 (50) | 4 (27) | 3 (43) | 2 (40) | 6 (33) | 11 (37) |

| Cytokine-release syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (29) | 0 | 4 (22) | 6 (20) |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 1 (17) | 4 (27) | 1 (14) | 2 (40) | 3 (17) | 6 (20) |

| Anemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 0 | 3 (17) | 4 (13) |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (22) | 4 (13) |

| Fatigue | 1 (33) | 0 | 1 (33) | 4 (67) | 6 (40) | 2 (29) | 0 | 2 (11) | 4 (13) |

| Injection site pain | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (22) | 4 (13) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 1 (17) | 2 (13) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 2 (11) | 4 (13) |

| Headache | 0 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 1 (17) | 4 (27) | 1 (14) | 0 | 2 (11) | 3 (10) |

| Hyperthermia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 2 (11) | 3 (10) |

| Hypotension | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 1 (17) | 2 (13) | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (6) | 2 (7) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless specified otherwise

AE adverse event

aThere were no grade 4/5 treatment-related AEs. There were 2 deaths, 1 in the monotherapy study and 1 in the combination study. Neither was determined by investigator to be treatment-related

b ≥ 10% of all patients in either study

Among patients treated with MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab, 28 of 30 (93%) experienced ≥ 1 treatment-related AE (Table 2). The most common treatment-related AEs were pyrexia (63%), chills (37%), nausea (20%), and cytokine-release syndrome (CRS; 20%). All CRS events were grade 1/2 and clinically manageable. Seven patients experienced grade 3 treatment-related AEs, including anemia and pyrexia (both n = 2; 7%) and hypertension and lymphopenia (both n = 1; 3%), as well as 1 patient who experienced both dyspnea and pleural effusion. In both the monotherapy and combination therapy studies, treatment-related constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, chills) were grade 1/2 and resolved within 24 h in the majority of affected patients. There were no grade 4/5 treatment-related AEs. One patient who received 0.8 mg MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab had treatment-related pleural effusion that led to discontinuation. One patient treated with 0.8 mg MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab died after a myocardial infarction that was not considered treatment-related. Grade 5 AEs were discussed on a multidisciplinary basis to confirm investigator judgement.

Efficacy

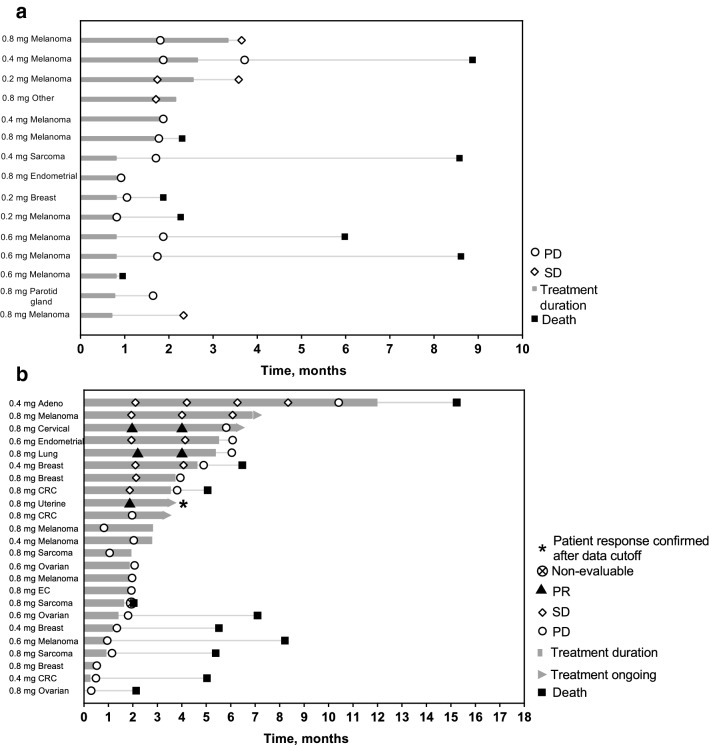

In the monotherapy study, there were no objective responses (unconfirmed) by investigator per irRECIST v1.1. A total of 4 patients had stable disease: 1 patient (melanoma) who received MK-4621 0.2 mg and 3 patients (2 with melanoma and 1 with cancer of unknown primary origin) who received with MK-4621 0.8 mg (Table 3, Fig. 1a).

Table 3.

Best overall response

| MK-4621 monotherapy (By investigator assessment per irRECIST v1.1, without confirmation) |

MK-4621 + pembrolizumab (By investigator assessment per RECIST v1.1, with confirmation) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MK-4621 0.2 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg n = 3 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg n = 6 |

MK-4621 0.4 mg + Pembro n = 7 |

MK-4621 0.6 mg + Pembro n = 5 |

MK-4621 0.8 mg + Pembro n = 18 |

|

| Best overall response, n (%) | |||||||

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11)a |

| SD | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 3 (50) | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 4 (22) |

| PD | 2 (67) | 3 (100) | 2 (67) | 3 (50) | 3 (43) | 3 (60) | 8 (44) |

| Unevaluableb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) |

| No assessmentc | 0 | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 3 (17) |

| ORR, % (95% CI) | 0 (0–70.8) | 0 (0–70.8) | 0 (0–70.8) | 0 (0–45.9) | 0 (0–41) | 0 (0–52) | 11 (1–35) |

CR complete response, irRECIST immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, ORR overall response rate, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, SD stable disease

aPR occurred in 1 patient with cervical cancer, 1 patient with lung cancer, and 1 patient with uterine (endometrial) cancer (this patient showed response prior to database cutoff but was confirmed after)

bInsufficient data for assessment of response

cNo postbaseline assessment of response

Fig. 1.

Time on study treatment and response based on investigator assessment per RECIST v1.1 for patients treated with (a) MK-4621 monotherapy and (b) MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy. c Maximum change in dimensions for injected and noninjected lesions for patients treated with MK-4621 + pembrolizumab. d Percentage change from baseline of target lesion (injected and noninjected) dimensions based on investigator assessment per RECIST v1.1 for patients enrolled in the combination study. *Indicates no change from baseline. CRC, colorectal cancer; EC, esophageal cancer; Adeno, adenoid-cystic carcinoma

In the combination study, the best overall confirmed responses by investigator per RECIST v1.1 were 2 patients who had a confirmed partial response (0.8 mg MK-4621; cervical cancer and lung cancer) and 1 additional patient who had a response confirmed after data cutoff (uterine cancer; Table 3, Fig. 1b). None of the patients in the combination study with a response had previously received an immune checkpoint inhibitor. In addition, 7 patients (MK-4621 0.4 mg, n = 2; MK-4621 0.6 mg, n = 1; MK-4621 0.8 mg, n = 4) had stable disease.

To characterize changes in tumor volume during treatment with MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab, tumor volume of both injected and noninjected tumors was reported as percentage change from baseline. The most substantial decrease in tumor volume was observed in patients with cervical cancer, lung cancer (both treated with MK-4621 0.8 mg plus pembrolizumab), and adenoid cystic carcinoma (MK-4621 0.4 mg plus pembrolizumab; Fig. 1c, d). Decrease in tumor size was observed in both injected and noninjected lesions.

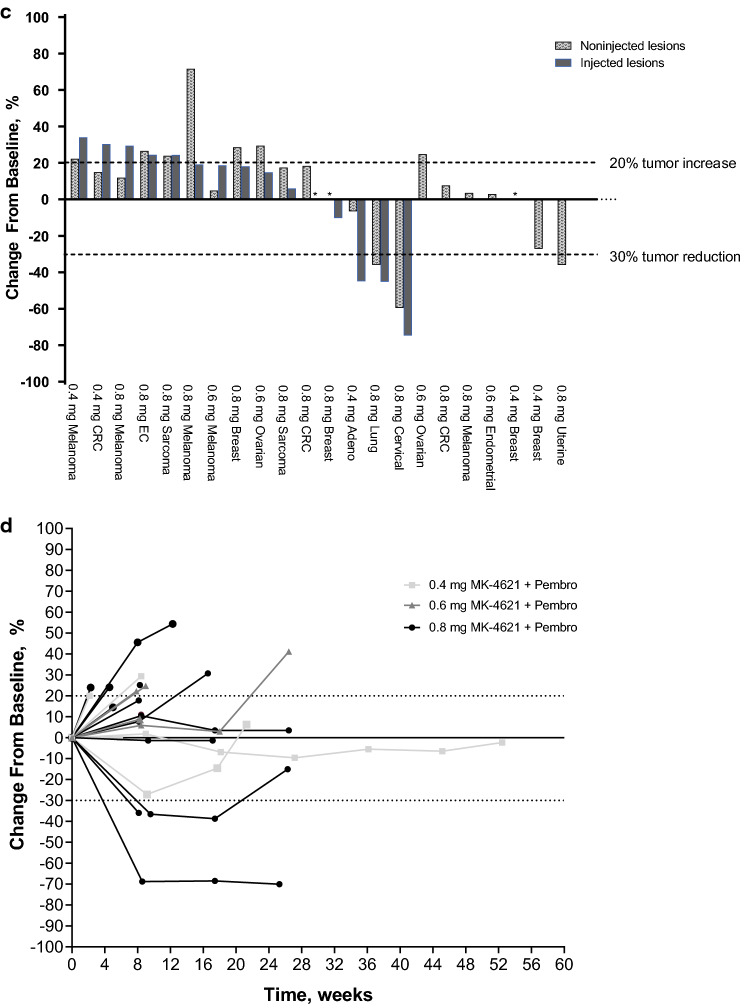

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma concentrations of MK-4621 after intratumoral injection of MK-4621 as monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab are shown in Fig. 2. Pharmacokinetics of MK-4621 were dose-proportional, with insignificant levels of MK-4621 observed in plasma from 2 h following injection on day 1 of cycle 1 and day 1 of cycle 2.

Fig. 2.

Plasma concentration of MK-4621 following intratumoral administration. a Patients treated with MK-4621 monotherapy. b Patients treated with MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy. Each line represents an individual patient. LOQ, limit of quantification

Biomarkers

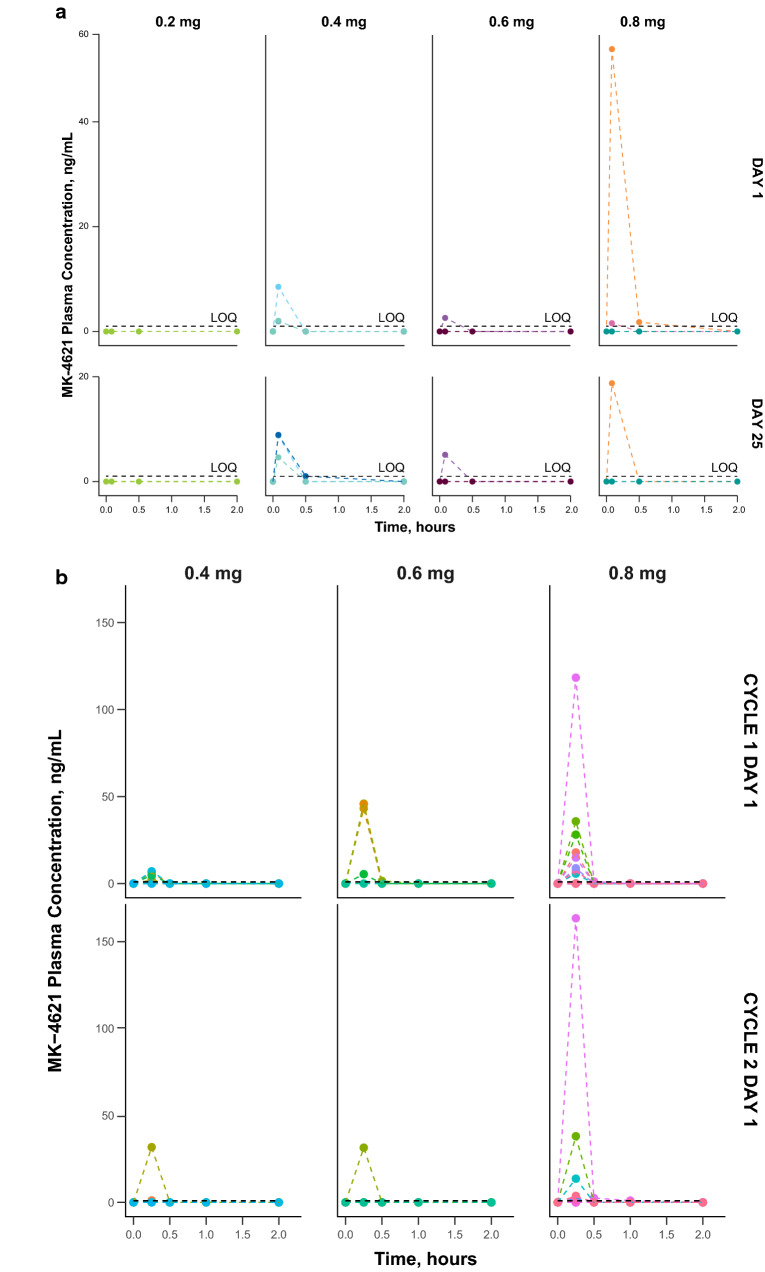

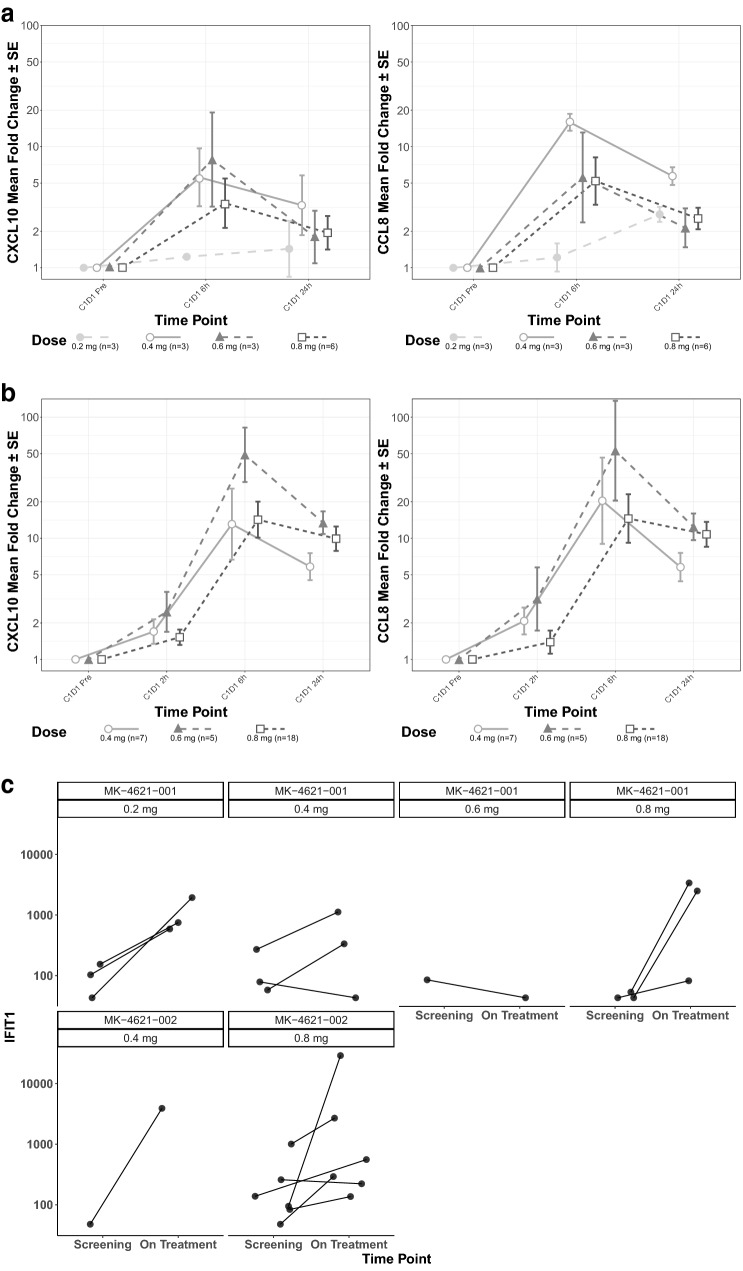

Evaluation of biomarkers that might provide insight into the mechanism of action of MK-4621 was an exploratory objective in both studies. At the 0.2-mg dose level, MK-4621 monotherapy did not mediate a change in CXCL10 serum levels, but CCL8 levels increased 24 h after injection (Fig. 3a, b). The other 3 MK-4621 dose levels were associated with a change in CXCL10 and CCL8 at both 6 and 24 h after injection. All 3 dose levels of MK-4621 plus pembrolizumab in the combination study mediated increases in serum concentrations of both CXCL10 and CCL8 after treatment at all time points (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

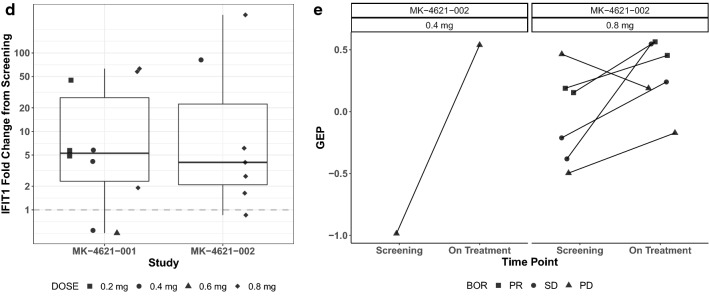

Type I IFN pathway biomarker expression. Serum fold-change of CXCL10 and CCL8 following treatment with MK-4621 in patients treated with (a) MK-4621 monotherapy and (b) MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy. IFIT1 fold change in tumor tissue from baseline (c) to week 5, day 29 among patients with paired baseline and on-treatment samples treated with MK-4621 monotherapy (n = 10) or MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy (n = 7) (paired samples are from the same patient but not necessarily from the same injected lesion) and (d) to cycle 3, day 1 for patients treated with MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy. (e) Change in TcellinfGEP from baseline to cycle 3, day 1 for patients treated with MK-4621 + pembrolizumab combination therapy (n = 7) (paired samples are from the same patient but not necessarily from the same injected lesion)

In addition to evaluating systemic pharmacodynamic biomarkers, the changes in expression of several genes involved in type I IFN signaling, such as IFIT1, were evaluated in tumor tissue collected at baseline and after treatment on week 5, day 29 in the monotherapy study and cycle 3, day 1 in the combination study. In most paired tumor samples from injected lesions, expression of these type I IFN–related genes increased after MK-4621 monotherapy (n = 10) and MK-4621 combination therapy with pembrolizumab (n = 7; Fig. 3c, d).

In paired tumor samples from injected lesions, TcellinfGEP scores tended to increase during combination therapy with MK-4621 and pembrolizumab (n = 7), though correlation with response could not be inferenced due to the small sample size (Fig. 3e); data were not available from the monotherapy study.

Tumor PD-L1 status (N = 21), TMB (N = 18), and TcellinfGEP (N = 28) were evaluated in the combination study. Among patients with an objective response, the patient with cervical cancer had a PD-L1 combined positive score of ≥ 50, the patient with NSCLC had a PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 10%, and the patient with uterine cancer had no PD-L1 data. Of the 3 patients with an objective response, 1 patient (NSCLC) had a tissue TMB score above the cutoff of 10 Mut/Mb [19]. In the remaining 2 patients, TMB status was not evaluable. Finally, all 3 patients with a response had a TcellinfGEP score above the cutoff of −0.318, which is conventionally used to define TcellinfGEP low vs. non-low (Supplementary Fig. 1). PD-L1 CPS, TcellinfGEP, and TMB for nonresponders are also shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Discussion

In these early phase studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of intratumoral injection of MK-4621 in patients with advanced solid tumors as a monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab, MK-4621 demonstrated acceptable safety and tolerability. MK-4621 alone had a favorable safety profile, with no treatment-related AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. The most common treatment-related AEs (pyrexia, fatigue, chills) were consistent with activation of the innate immune system. Similarly, when combined with pembrolizumab, MK-4621 was tolerated and there was no evidence of exacerbated or unexpected toxicity. There were no grade 4/5 treatment-related AEs. The MTD of MK-4621 was not reached in either study, and the highest dose evaluated (MK-4621 0.8 mg) was tolerated as both a monotherapy and in combination with pembrolizumab.

No responses were observed in the monotherapy study. Three patients treated with the combination experienced a partial response. In patients in the combination study, we evaluated PD-L1, tissue TMB, and TcellinfGEP, predictive biomarkers that have all been shown to correlate with response to pembrolizumab across multiple tumor types [20, 21]. Of the 3 responders, 2 had PD-L1–positive tumors (the third patient had an unknown PD-L1 status). One of the 3 responders had high TMB status (the other 2 responders had unknown TMB status), and all 3 responders had a high TcellinfGEP score. These biomarker findings are predictive of pembrolizumab monotherapy responses, and the 3 responders had tumor types for which pembrolizumab monotherapy has shown efficacy (small-cell lung cancer, cervical cancer, and uterine [i.e., endometrial] cancer) [22]. It was not possible to unequivocally determine whether these systemic antitumor effects were mediated or augmented by MK-4621 administration.

Pharmacokinetic analyses showed systemic exposures generally increased with dose of MK-4621 after administration as monotherapy and when combined with pembrolizumab. Notably, systemic exposures were transient, with little evidence of exposure > 1 h after intratumoral injection. MK-4621 is administered intratumorally because it is unlikely that biologically effective doses could be achieved with systemic administration. Such local administration maximizes tumor exposure while mitigating against the potential for toxicity with systemic administration [23].

To evaluate pharmacodynamic changes mediated by MK-4621, we assessed biomarker parameters both in serum and in tumor tissue. CXCL10 and CCL8 expression in the serum increased upon injection with MK-4621 in both studies, similar to what is observed in preclinical models [10]. Interestingly, the lower doses of MK-4621 in the combination study increased CXCL10 expression, unlike the lower doses of MK-4621 alone, suggesting a potential interaction. We also measured IFIT1 gene expression changes in injected tumor biopsies to determine local changes to IFN signaling [24]. In most tumors, IFIT1 gene expression increased upon injection of MK-4621 compared with baseline biopsies, suggesting local activation of the RIG-I pathway. We also observed a high frequency of febrile reactions among patients treated with MK-4621 in both studies. Collectively, these data, at the doses tested, support the proposed mechanism of action of MK-4621 activation of RIG-I and subsequent activation of the type I IFN pathway and the innate immune system.

There are limited published data from clinical studies of intratumorally injected agents that have activation of innate immunity as the principal mechanism of action. Some of these studies have evaluated activators of toll-like receptor (TLR) family members that, similar to RIG-I, are involved in recognition of viral nucleotides and induce type I IFN production, activating an innate immune response [25]. These studies yielded similar results to those that we have observed with MK-4621. SD-101, a synthetic CpG oligonucleotide that stimulates TLR9, showed modest antitumor activity in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced melanoma [26]. Genes representing different immune cell types and IFN-α responsive genes showed increased expression, suggesting activation of the innate immune system. Similarly, MEDI9197, an intratumorally injected TLR7 and 8 agonist, was evaluated with or without durvalumab and/or palliative care radiation therapy in patients with advanced solid tumors [27]. There were no objective responses, but 13 of 52 (25%) patients exhibited stable disease for ≥ 8 weeks. Similar to MK-4621, plasma levels of MEDI9197 were low, and IFN-γ, CXCL10, and CXCL11 increased after administration, suggesting increased innate immune activity. Finally, in a study of the TLR agonist BO-112 (a synthetic, double-stranded, non-coding RNA polyinosinicolycytidylic acid nanoplexed with PEI) in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in patients previously refractory to anti–PD-1 therapies, 3 of 12 patients had a response [28]. In some patients, treatment with BO-112 was associated with changes in IFN-related genes.

Collectively, the limited data from studies of intratumoral agents activating the innate immune system suggest that further understanding of innate immune activation, and the connection to overall clinical efficacy of these agents, is warranted. These studies show potential induction of local and systemic immune activation; however, the clinical efficacy of these agents in the context of tumor immunotherapy is limited.

In conclusion, MK-4621 exhibited a manageable safety profile, but modest antitumor activity. Analysis of biomarkers in a subset of patients suggested that MK-4621 activated the RIG-I pathway, as exhibited through an increase in gene expression of IFN signaling pathway members and associated chemokines and cytokines, but without evidence for downstream events necessary for immune-mediated tumor cell killing. At the doses tested here, MK-4621 has not demonstrated clinically significant efficacy in patients with pretreated advanced solid tumors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by Rigontec GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. We thank the patients and their families and caregivers for participating in this study, along with all investigators and site personnel. We thank Xuemei Zhao and Manuela Niewel for work on biomarkers and statistical analysis. Medical writing assistance was provided by Kathleen Estes, PhD, of ICON plc (Blue Bell, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse event

- CCL8

C–C motif chemokine ligand 8

- CRS

Cytokine-release syndrome

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4

- CXCL10

C‒X‒C motif chemokine ligand 10

- DLT

Dose-limiting toxicity

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- IFIT1

Interferon-induced proteins with tetratricopeptide repeats 1

- IFN

Interferon

- irRECIST

Immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- MTD

Maximum tolerated dose

- NSCLC

Non–small-cell lung cancer

- NCI-CTCAE

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed death ligand-1

- PEI

Polyethylenimine

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- RIG-I

Retinoic acid–inducible gene I

- TcellinfGEP

cell-inflamed gene expression profile

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TMB

Tumor mutational burden

Author contributions

EC and KD designed the studies. VM, EC, MRM, FB, CG-M, AI, ER, AM, and MW enrolled and treated patients. YZ did statistical analyses. VM, EC, MRM, FB, CG-M, AI, ER, AM, EC, KD, HZ, EC, YZ, MW participated in writing the draft and/or reviewing it for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding

This work was supported by Rigontec GmbH, a wholly owned subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

V. Moreno: consulting fees from: Bayer, Pieris, BMS, Janssen. Traveling support from: Regeneron/Sanofi, BMS, Bayer. Speaker´s Bureau: Nanobiotix, BMS, Bayer. Educational Grant: Medscape/Bayer. E. Calvo: Advisory: Adcendo, Alkermes, Amunix, Anaveon, Amcure, AstraZeneca, BMS, Janssen, MonTa, MSD, Nanobiotix, Nouscom, Novartis, OncoDNA, PharmaMar, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Servier, SyneosHealth, TargImmune, T-knife; Research grants: Achilles, BeiGene (IDMC steering committee), EORTC IDMC (non-financial interest), MedSIR (steering committee); Scientific Board: Adcendo, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, PsiOxus Therapeutics; Employee: HM Hospitals Group and START Program of Early Phase Clinical Drug Development in Oncology; Medical Oncologist, Clinical Investigator; Director, Clinical Research Ownership: START corporation; Oncoart Associated; International Cancer Consultants; Non-profit Foundation INTHEOS (Investigational Therapeutics in Oncological Sciences): founder and president. M. R. Middleton: Dr. Middleton reports grants from Roche and AstraZeneca; grants and personal fees from GSK, personal fees and other from Novartis, Immunocore, Bristol-Myers Squibb, other from Millenium, Pfizer, Regeneron, personal fees, non-financial support, and other from Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA; personal fees and other from BiolineRx, personal fees and non-financial support from Replimune, personal fees from Kineta and Silicon Therapeutics, and personal fees from Silicon Therapeutics outside the submitted work. F. Barlesi: personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer–Ingelheim, Eli Lilly Oncology, F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd, Novartis, Merck, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, and Takeda. C. Gaudy-Marqueste: Honoraria for lectures by Bristol-Myers Squibb; travel support from MSD, BMS, Pierre Fabre. A. Italiano: grants to institution from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, Roche, Springworks, Epizyme; and consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Roche, Daiichi-Sankyo. E. Romano: travel support from MSD for participation in a scientific meeting outside the topic of the submitted work. A. Marabelle: institutional research funding from MSD; grant from Fondation MSD Avenir outside the topic of the manuscript; and honoraria and travel expenses for participation in a scientific advisory board from MSD outside the topic of the submitted work. E. Chartash: employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and stockholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. K. Dobrenkov: employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and stockholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. H. Zhou: employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. E.C. Connors: employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and stockholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. Y. Zhang: employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and stockholder in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. M. Wermke: Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA for funding of study and professional medical writing; research funding to institution from Roche; consulting fees from Novartis, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gemoab, Roche, Takeda, Lilly, MSD, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immatics; honoraria from Novartis and Roche; travel support from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Pfizer; and participation on data safety monitoring board or advisory board for ISA Therapeutics.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Procedures were approved by an institutional review/ethics committee at each site. Patients provided written informed consent.

Data sharing statement

Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (MSD), is committed to providing qualified scientific researchers access to anonymized data and clinical study reports from the company’s clinical trials for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. MSD is also obligated to protect the rights and privacy of trial participants and, as such, has a procedure in place for evaluating and fulfilling requests for sharing company clinical trial data with qualified external scientific researchers. The MSD data sharing website (available at: http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php) outlines the process and requirements for submitting a data request. Applications will be promptly assessed for completeness and policy compliance. Feasible requests will be reviewed by a committee of MSD subject matter experts to assess the scientific validity of the request and the qualifications of the requestors. In line with data privacy legislation, submitters of approved requests must enter into a standard data-sharing agreement with MSD before data access is granted. Data will be made available for request after product approval in the US and EU or after product development is discontinued. There are circumstances that may prevent MSD from sharing requested data, including country or region-specific regulations. If the request is declined, it will be communicated to the investigator. Access to genetic or exploratory biomarker data requires a detailed, hypothesis-driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and MSD subject matter experts; after approval of the statistical analysis plan and execution of a data-sharing agreement, MSD will either perform the proposed analyses and share the results with the requestor or will construct biomarker covariates and add them to a file with clinical data that is uploaded to an analysis portal so that the requestor can perform the proposed analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan CA, Reader J, Roque DM. Review of immune therapies targeting ovarian cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19:74. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0584-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morse MA, Hochster H, Benson A. Perspectives on treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Oncologist. 2020;25:33–45. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rameshbabu S, Labadie BW, Argulian A, Patnaik A. Targeting innate immunity in cancer therapy. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:138. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hegde PS, Karanikas V, Evers S. The where, the when, and the how of immune monitoring for cancer immunotherapies in the era of checkpoint inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1865–1874. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kell AM, Gale M., Jr RIG-I in RNA virus recognition. Virology. 2015;479–480:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elion DL, Jacobson ME, Hicks DJ, Rahman B, Sanchez V, Gonzales-Ericsson PI, Fedorova O, Pyle AM, Wilson JT, Cook RS. Therapeutically active RIG-I agonist induces immunogenic tumor cell killing in breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2018;78:6183–6195. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nri3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besch R, Poeck H, Hohenauer T, Senft D, Häcker G, Berking C, Hornung V, Endres S, Ruzicka T, Rothenfusser S, Hartmann G. Proapoptotic signaling induced by RIG-I and MDA-5 results in type I interferon-independent apoptosis in human melanoma cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2399–2411. doi: 10.1172/jci37155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elion DL, Cook RS. Activation of RIG-I signaling to increase the pro-inflammatory phenotype of a tumor. Oncotarget. 2019;10:2338–2339. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barsoum J, Renn M, Schuberth C, Jakobs C, Schwickart A, Schlee M, van den Boorn J, Hartmann G. Selective stimulation of RIG-I with a novel synthetic RNA induces strong anti-tumor immunity in mouse tumor models (abstract) Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:B44. doi: 10.1158/2326-6074.Tumimm16-b44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji Y, Wang SJ. Modified toxicity probability interval design: a safer and more reliable method than the 3 + 3 design for practical phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1785–1791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, Ford R, Schwartz LH, Mandrekar S, Lin NU, Litière S, Dancey J, Chen A, Hodi FS, Therasse P, Hoekstra OS, Shankar LK, Wolchok JD, Ballinger M, Caramella C, de Vries EGE. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e143–e152. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Michal JJ, Zhang L, Ding B, Lunney JK, Liu B, Jiang Z. Interferon induced IFIT family genes in host antiviral defense. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:200–208. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pidugu VK, Pidugu HB, Wu MM, Liu CJ, Lee TC. Emerging functions of human IFIT proteins in cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:148. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, Murphy E, Loboda A, Kaufman DR, Albright A, Cheng JD, Kang SP, Shankaran V, Piha-Paul SA, Yearley J, Seiwert TY, Ribas A, McClanahan TK. IFN-gamma-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2930–2940. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dufour JH, Dziejman M, Liu MT, Leung JH, Lane TE, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J Immunol. 2002;168:3195–3204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruhwald M, Bodmer T, Maier C, Jepsen M, Haaland MB, Eugen-Olsen J, Ravn P, Tbnet, Evaluating the potential of IP-10 and MCP-2 as biomarkers for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1607–1615. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00055508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, Chung HC, Kindler HL, Lopez-Martin JA, Miller WH, Jr, Italiano A, Kao S, Piha-Paul SA, Delord JP, McWilliams RR, Fabrizio DA, Aurora-Garg D, Xu L, Jin F, Norwood K, Bang YJ. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott PA, Bang YJ, Piha-Paul SA, Razak ARA, Bennouna J, Soria JC, Rugo HS, Cohen RB, O'Neil BH, Mehnert JM, Lopez J, Doi T, van Brummelen EMJ, Cristescu R, Yang P, Emancipator K, Stein K, Ayers M, Joe AK, Lunceford JK (2019) T-cell-inflamed gene-expression profile, programmed death ligand 1 expression, and tumor mutational burden predict efficacy in patients treated with pembrolizumab across 20 cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J Clin Oncol 37:318–327 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.2276 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhu J, Zhang T, Li J, Lin J, Liang W, Huang W, Wan N, Jiang J. Association between tumor mutation burden (TMB) and outcomes of cancer patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitions: a meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:673. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keytruda® (pembrolizumab). Full Prescribing Information, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, Rahway, NJ, USA, 2021

- 23.Marabelle A, Tselikas L, de Baere T, Houot R (2017) Intratumoral immunotherapy: using the tumor as the remedy. Ann Oncol 28:xii33-xii43 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx683 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Fensterl V, Sen GC. Interferon-induced Ifit proteins: their role in viral pathogenesis. J Virol. 2015;89:2462–2468. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02744-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribas A, Medina T, Kummar S, Amin A, Kalbasi A, Drabick JJ, Barve M, Daniels GA, Wong DJ, Schmidt EV, Candia AF, Coffman RL, Leung ACF, Janssen RS. SD-101 in combination with pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma: results of a phase Ib, multicenter study. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1250–1257. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siu L, Brody J, Gupta S, Marabelle A, Jimeno A, Munster P, Grilley-Olson J, Rook AH, Hollebecque A, Wong RKS, Welsh JW, Wu Y, Morehouse C, Hamid O, Walcott F, Cooper ZA, Kumar R, Ferte C, Hong DS. Safety and clinical activity of intratumoral MEDI9197 alone and in combination with durvalumab and/or palliative radiation therapy in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e001095. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquez-Rodas I, Longo F, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Calles A, Ponce S, Jove M, Rubio-Viqueira B, Perez-Gracia JL, Gomez-Rueda A, Lopez-Tarruella S, Ponz-Sarvise M, Alvarez R, Soria-Rivas A, de Miguel E, Ramos-Medina R, Castanon E, Gajate P, Sempere-Ortega C, Jimenez-Aguilar E, Aznar MA, Calvo A, Lopez-Casas PP, Martin-Algarra S, Martin M, Tersago D, Quintero M, Melero I (2020) Intratumoral nanoplexed poly I:C BO-112 in combination with systemic anti-PD-1 for patients with anti-PD-1-refractory tumors. Sci Transl Med 12:eabb0391 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb0391 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.