Abstract

Bromo- and extra-terminal domain (BET) inhibitors represent potential therapeutic approaches in solid and hematological malignancies that are currently analyzed in several clinical trials. Additionally, BET are involved in the epigenetic regulation of immune responses by macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), that play a central role in the regulation of immune responses, indicating that cancer treatment with BET inhibitors can promote immunosuppressive effects. The aim of this study was to further characterize the effects of selective BET inhibition by JQ1 on DC maturation and DC-mediated antigen-specific T-cell responses. Selective BET inhibition by JQ1 impairs LPS-induced DC maturation and inhibits the migrational activity of DCs, while antigen uptake is not affected. JQ1-treated DCs show reduced ability to induce antigen-specific T-cell proliferation. Moreover, antigen-specific T cells co-cultured with JQ1-treated DCs exhibit an inactive phenotype and reduced cytokine production. JQ1-treated mice show reduced immune responses in vivo to sublethal doses of LPS, characterized by a reduced white blood cell count, an immature phenotype of splenic DCs and T cells and lower blood levels of IL-6. In our study, we demonstrate that selective BET inhibition by JQ1, a drug currently tested in clinical trials for malignant diseases, has profound effects on DC maturation and DC-mediated antigen-specific T-cell responses. These immunosuppressive effects can result in the induction of possible infectious side effects in cancer treatments. In addition, based on our results, these compounds should not be used in combinatorial regimes using immunotherapeutic approaches such as check point inhibitors, T-cell therapies, or vaccines.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00262-020-02665-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: JQ1, BET inhibition, Dendritic cells, T cells, Cancer

Introduction

As part of the quest of developing new therapeutic approaches, bromo- and extra-terminal domain (BET) proteins got into the focus as possible targets in various cancer entities, as well as metabolic and inflammatory diseases [1]. Members of the BET family are bromodomain containing reader proteins that specifically recognize acetylated chromatin sites and, thus, promote gene expression by activation of transcriptional factors [2]. Thus, there are two conceivable ways of pathogenesis: First, mutations that immediately interfere with the activity or expression of bromodomains can be the primary cause of diseases. On the other hand, intact bromodomains can convey a pathologic gene expression caused by faulty preceding mechanics. In both cases, specific inhibition of bromodomains seems promising.

The small molecule JQ1 was developed as a potent competitive inhibitor of the BET family, especially bromodomain containing protein 4 (BRD4), which was shown to be highly active in postmitotic gene transcription and among others provides the expression of c-Myc [2, 3]. Mutations in the BRD4 gene were associated with respiratory tract carcinoma [4]. BET inhibition in general and specifically treatment with JQ1, on the other hand, has anti-proliferative effects in hematologic malignancies, acts anti-tumorous, and increases the effectiveness of chemotherapy in colon and gastric cancer cell lines [1, 3].

Furthermore, BET inhibition has shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory and antiviral capacities by inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells’ (NF-κB) signaling [2, 5, 6]. The immune suppressive capacity of BET inhibitors might, therefore, interfere with the induction of anti-tumor immune responses via dendritic cells (DCs) and antigen-specific T cells, which play a pivotal role in cancer immunotherapies [7, 8].

DCs are professional antigen presenting cells (APC) that act as major link between the innate and adaptive immune system by the ability of inducing T-cell anergy and activity [9], crucial for the induction of a robust anti-cancer immunity. DCs descend under influence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and tumor necrosis factor beta (TNFβ) from the myeloid progenitor cells [9]. DCs differ from other phagocytes like macrophages and neutrophils in effectiveness of antigen uptake by phagocytosis, micropinocytosis, and adsorptive endocytosis. Furthermore antigens are not split into amino acids, but processed and transferred to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules for antigen presentation on the cell surface [10, 11].

Immature DCs reside in tissue processing large amount of antigens. By recognizing bacteria or lipopolysaccharides (LPS) via pattern recognition receptors (PRR) or after contact with cytokines (interleukin-1 [IL-1], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNFα], and GM-CSF), NF-κB signaling is activated which leads to cell maturation a process that is inhibited by interleukin-10 (IL-10) [10, 12]. During maturation, macropinocytosis activity is initially increased to maximize antigen uptake [13], while again being down regulated in the continuing process [14]. Phenotypic correlate of maturation is the transfer of peptide-loaded MHC class II complexes to the cell surface as well as expression of the surface markers CD40,CD54, CD80, CD83, CD86, and production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-12 (IL-12), interleukin-23 (IL-23), and TNFα [10]. Furthermore expression of C-C chemokine receptor type (CCR) 7 is upregulated, while CCR5 and CCR6 are decreased which leads to migration towards draining lymphatic vessels and ultimately lymph nodes [9], where antigens are transmitted to resident DCs to increase effectiveness of antigen presentation [15].

In the lymph nodes DCs attract naïve T cells by secretion of C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL) 18 [16]. Proliferation and differentiation of naïve T cells depend on three signals, whereas signal 1 is the coreceptor (CD4, respectively, CD8) driven antigen-specific recognition of peptide-loaded MHC molecules by the T-cell receptor [9]. In the absence of further signaling, tolerance towards the antigen is induced [17]. Signal 2 is the interaction of the DCs’ costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 with T-cell CD28, whereby T-cell proliferation is induced by starting G1 phase of cell cycle and NF-κB-driven promotion of autocrine IL-2 production and interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) completion [18, 19]. Signal 2 is strengthened by receptor pairs CD27 and CD70 as well as CD40L and CD40 [20]. Signal 3 determines the subset of T-cell differentiation and consists of the DC’s cytokine profile, which again is determined upon first encounter with the antigen [17, 21]. Contact of naïve T cells with immature DCs induces anergy and activates regulatory T cells, thus limiting immune responses [22].

Although BET inhibitors have shown efficacy in a variety of pre-clinical models of malignancy and are currently getting evaluated in clinical trials for several cancer entities, we do not have a complete understanding of its impact on the immune system, particularly the adaptive immune responses.

In this study, we analyzed the effects of BET inhibition by JQ1 on murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) and human monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) activation and function, as well as the DC-mediated antigen-specific T-cell responses in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were used as organ donors and for in vivo experiments. Isolated T cells from C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/Crl (OT I Mouse) and C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/Crl (OT II Mouse) were used in antigen-specific proliferation assays.

Generation of dendritic cells

Generation of BMDCs was performed as previously described [23]. Briefly, bone marrow was flushed from femur and tibia of 8 to 16 weeks old male and female C57BL/6 mice in an aseptic environment and filtered using a 70 µm cell strainer. Erythrocytes were eliminated using RBC Lysis Buffer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Mature macrophages were sorted out by adherence to plastic for 30 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The remainig cells were taken up into culture medium (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0.5% beta-mercaptoethanol [β-ME ] [each Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE]) containing recombinant murine GM-CSF [10 ng/mL, PeproTech Germany, Hamburg, Germany) for 7 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2. On day 3 70% of the supernatant including loose cells were discarded and replaced with fresh medium. On day 6 again 70% of the supernatant were substituted while this time the included cells were saved and resolved. On day 7 the cells were examined for purity marked by CD11c and used for further investigation.

Human MoDCs were generated from peripheral blood by plastic adherence as previously described [24]. Adherent monocytes were cultured in RP10 medium supplemented with GM-CSF (100 ng/mL; PeproTech) and IL-4 (20 ng/mL; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). Cytokines were added every other day.

Isolation of splenic cells

After manually crushing the spleen using a 70 µm cell strainer CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated by positive selection using the respective magnetic cell separation (MACS) Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For isolation of splenic dendritic cells, the spleen was first flushed and incubated for 30 min with Collagenase D (400 U/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Purification was performed by negative selection of the CD11c+ population by MACS (Pan Dendritic Cell Isolation Kit, Miltenyi Biotec).

Drug treatment of DCs

On day 7 of culture, BMDCs were treated with (+)-JQ1 BET bromodomain Inhibitor (ApexBio, Houston, TX) in concentration between 50 and 500 nM. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added in corresponding concentration as control. After 24 h cells were challenged with LPS (0.5 µg/mL, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for another 24 h. BMDCs and supernatant were then harvested and used for further investigation.

Human MoDC were treated from d0 of generation with (+)-JQ1.

Cell viability assay

DC viability was examined by flow cytometry using the Pacific Blue™ Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with Propidium Iodide (BioLegend) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transwell migration assay

For evaluation of the migratory capacity, JQ1/DMSO-treated and LPS-challenged BMDCs were suspended in serum free medium at 1.5 M cells per mL. 100 µL of the suspension were transferred to the upper part of a Corning® Costar® Transwell® cell culture insert (pore size 5 µm; Corning Inc., Corning, NY). After 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 cells adhered to the membrane and recombinant murine, CCL19 was added to the lower part of the chamber (600 ng/mL; PeproTech Germany, Hamburg, Germany). After another 4 h of incubation, migrated cells in the lower chamber were manually counted using a hemocytometer.

MoDCs were seeded in a total of 1 × 105 cells into a transwell chamber (8 μm, BD Falcon; BD Biosciences) in a 24-well plate, and migration to CCL19/macrophage inflammatory protein-3 beta (MIP-3β) was analyzed after 4 h by counting gated DCs for 1 min in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) cytometer [24].

Evaluation of antigen uptake

JQ1/DMSO-treated BMDCs with or without LPS activation were exposed to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) marked dextrans (average molecular weight 70 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 1 mg/mL for 30 min and after repeated resuspension analyzed by flow cytometry for antigen uptake.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared and protein concentrations were determined as described previously [24, 25]. The blot was probed with monoclonal antibodies against signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B (STAT5B), extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and p38 as well as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as loading control (each purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). For analysis of the activation state of STAT5B, ERK1/2 and p38 phospho-specific antibodies were used. Protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL).

T-cell proliferation and activation assay

BMDCs on day 7 of culture were transferred to RPMImax Medium (RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 0,5% β-ME, 1% l-Glutamine, 1% Sodium Pyruvate, 1% MEM Non Essential [each Thermo-Fisher Scientific]), treated with various concentrations of JQ1/DMSO and challenged with full ovalbumin (OVA) over night [100 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). 4 × 104 BMDCs were co-cultured with 1.6 × 105 Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) stained splenic CD4+ T cells from OT II mice, respectively, CD8+ T cells from OT I mice, in 200 µL RPMImax.

For analysis of T-cell proliferation in the absence of DCs, flat bottomed culture plates were treated with Dynabeads® Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) at 5 µg/mL and 4 °C over night. The solution was discarded right before adding the CFSE-stained T cells (2 × 105 in 200 µL) in RPMIMax medium-containing IL-2 [100 U/mL; Peprotrech) which were then treated with JQ1/DMSO. The T cells were analyzed for proliferation and activation by flow cytometry after 48 h. The proliferation index and number of cell divisions were calculated using FlowJo V10 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT qPCR)

Isolation of RNA from cell pellets was performed using the RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit from Qiagen (Venlo, Netherlands). Reverse transcription to cDNA was executed using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT qPCR was performed in triplicates using SensiMix™ SYBR No-ROX from Bioline (London, United Kingdom) on aMasterCycler® RealPlex 2 (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). RNA expression was normalized to GAPDH and the fold increase was determined by dividing each sample’s expression by that of BMDCs’ controls.

Flow cytometry of surface markers and intracellular cytokines

Staining of surface molecules was performed in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). First blockage of Fc receptors was achieved by adding 1 µL TruStain fcX™ (anti-mouse CD16/CD32) antibody (Biolegend) per 100 µL cell suspension. After incubation protected from light at 4 °C for 20 min, the staining antibodies were added in concentration between 1:100 and 1:400. After another light-protected incubation at 4 °C for 45 min. Flow cytometry was performed using an FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), while the results were analyzed using FlowJo V10. For intracellular staining of cytokines, Monensin Solution (1:1000, eBioscience, Santa Clara, CA) was added to the cell culture 4 h before harvesting the cells. To attain cell wall permeability, the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (Becton Dickinson) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by Fc receptor blockage and antibody staining as described.

Determination of IL-6 production

IL-6 secretion in cell culture supernatant and mouse serum was measured using the OptEIA™ Mouse IL-6 Elisa Set (Becton Dickinson) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistic

The data are shown as mean + standard deviation (SD) with P value related to the DMSO control group (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001; ns P ≥ 0.05). Significance was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test (unpaired for replicates of the same experiment, paired for pooled experiments) when there were only two groups. For multiple groups, the one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was employed. For performing calculations and creation of diagrams, Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used.

Results

In the following explanation, JQ1-treated cells’, respectively, mice were compared to a control that was treated with the carrier solution DMSO, in which the DMSO concentration corresponds with the highest used JQ1 concentration.

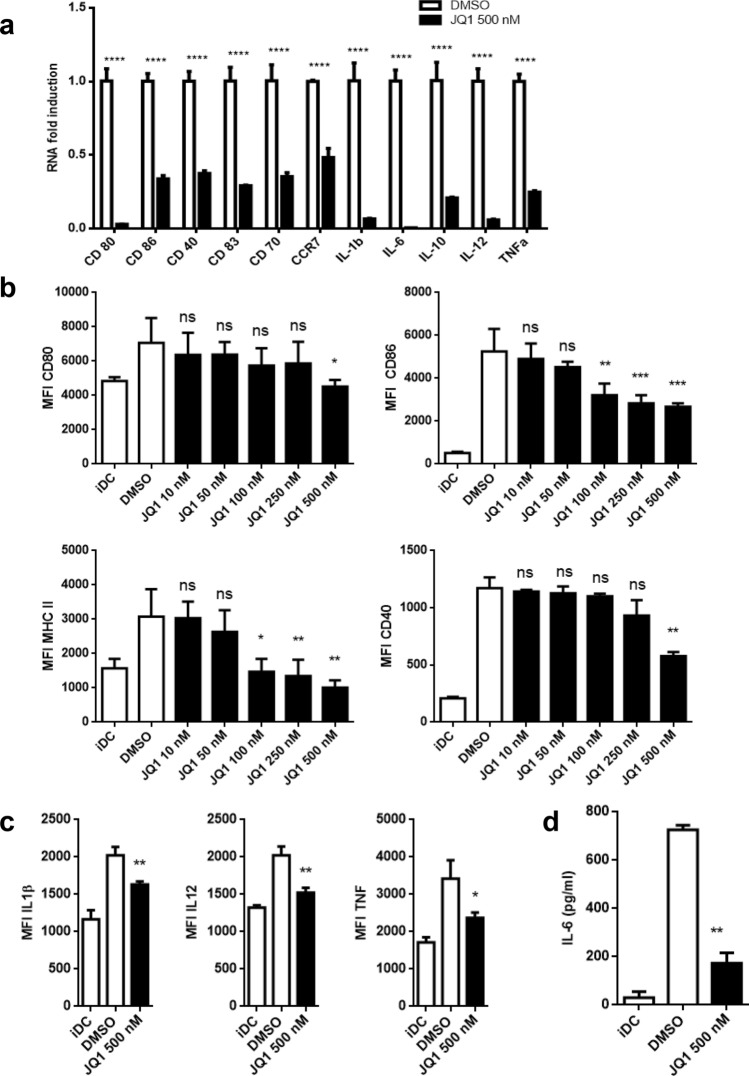

JQ1 impairs activation of murine BMDCs

We first tested the effect of JQ1 on the LPS-induced activation of BMDCs. On day 7 of culture, BMDCs were treated with JQ1 overnight and subsequently challenged with LPS for 24 h. We were able to show a dose-dependent reduction in the expression of CD80, CD 86, CD40, and MHC class II (I-A/I-E), markers that are associated with the mature phenotype of murine DCs. This is consistent with significantly impaired RNA levels of said markers and, furthermore, CD70 and CCR7 as well as the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, TNFα, and also IL-10 (Fig. 1a, b). Matching with these findings, intracellular levels of IL-1β, IL-12, and TNFα are reduced (Fig. 1c) as well as the presence of IL-6 in the cell culture’s supernatant (Fig. 1d). JQ1 did not affect BDMC viability (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

JQ1 impairs activation and modulates cytokine production of murine BMDCs. BMDC were treated with JQ1 (filled square), respectively, DMSO (open square) on day 7 of culture overnight and challenged with LPS for 24 h. Immature DC (iDC) were DMSO-treated without final LPS challenge. a Relative RNA fold induction of surface molecules and chemokines, normalized to DMSO control. Triplicates of one experiment that stands representative for 3. b Expression of surface molecules after JQ1 treatment in varying doses [10, 50, 100, 250, and 500 nM) are shown. Pooling of three independent experiments. c Immunostaining of intracellular cytokines. Triplicates of one experiment. d Supernatant of cell culture was collected and analyzed for IL-6 production by ELISA. Pooling of three independent experiments

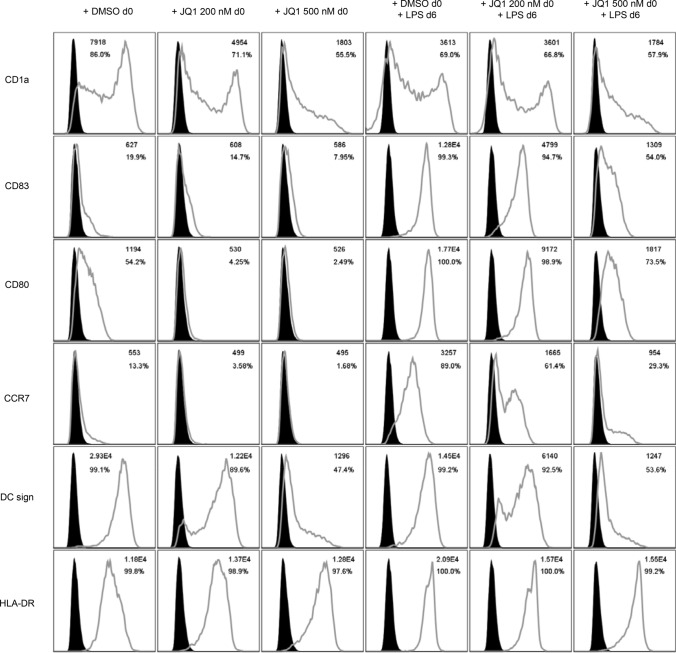

JQ1 impairs the phenotype of human MoDCs

Consisting with our findings in murine BMDC, human peripheral blood monocytes cultured under DC-driving conditions while treated with JQ1 with final LPS stimulation show an immature phenotype compared to the vehicle control, as the expression of the activation markers CD83, CD80, and CCR7 is dose-dependently reduced among mature MoDCs. Interestingly, in contrast to murine BMDC, we did not observe a reduced expression of MHC class II complex (HLA-DR). Furthermore, monocytes treated with JQ1 during development did not resemble dendritic cells, as the DC-specific surface markers CD1a and DC sign were not upregulated in the process (Fig. 2). Incubation of MoDCs with JQ1 had no effect on HLA class I expression as analyzed by flow cytometry using an HLA ABC-binding monoclonal antibody (mAb) as described previously [26] (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

JQ1 impairs the phenotype of human MoDCs: Human monocytes cultured under DC-driving conditions with or without final LPS stimulation were exposed to different concentrations of JQ1 (200 and 500 nM) or DMSO throughout the differentiation period and analyzed for expression of DC and activation markers. Filled black graphs represent negative controls. Results are from 1 experiment representative of at least 3

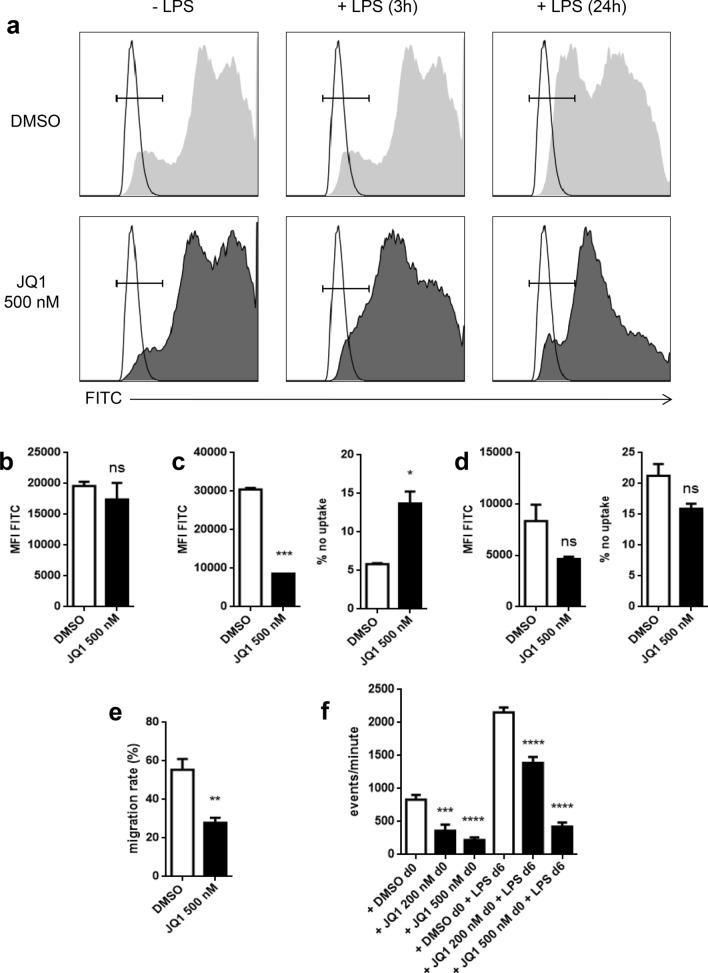

Effect of JQ1 on BMDCs antigen uptake

We wanted to investigate if the immature phenotype of JQ1-treated and LPS-challenged BMDCs might be the result of a general reduced antigen uptake. We showed, based on FITC-marked dextrans, that JQ1 has no effect on antigen uptake of immature BMDCs (Fig. 3a, b). On the other hand, shortly after LPS challenge (3 h), JQ1 treatment leads to a reduced dextran uptake (Fig. 3a, c). Interestingly, at a later time point (24 h after LPS challenge), the difference in antigen uptake between JQ1-treated BMDC and the vehicle control is reduced and we could even observe a non significant trend towards a higher percentage of cells with no antigen uptake in the control group (Fig. 3a, d).

Fig. 3.

Effects of JQ1 on BMDC antigen uptake and DC migration. a–d BMDC with or without LPS were exposed to FITC-marked dextrans for 30 min. a Exemplary histograms. Unstained controls with corresponding population are shown transparent. b FITC MFI of immature BMDCs. Pooling of three independent experiments. c FITC MFI and negative population 3 h after LPS challenge. Pooling of two independent experiments. d FITC MFI and negative population 24 h after LPS challenge. Pooling of two independent experiments. e Proportion of migrated BMDC in a CCL19-driven transwell migration assay 24 h after JQ1/DMSO treatment. Pooled results of three independent experiments. f Human monocytes cultured under DC-driving conditions with or without final LPS stimulation were exposed to different concentrations of JQ1 (filled square) or DMSO (open square). Migratory behavior toward CCL19/MIP-3β was assessed in transwell assays. Evaluation of quadruplicates of a single experiment that is representative for three experiments

JQ1-treated DCs display reduced migratory capacity

DCs are guided towards draining lymph nodes by a gradient in CCL19 concentration [9]. Since we already observed lower mRNA levels of the corresponding chemokine receptor CCR7, reduced migratory capacity of JQ1-treated DCs was assumed. Indeed, LPS-challenged and JQ1-treated BMDCs show a significant reduction in active migration in vitro (Fig. 3e). Concurring, the same result was observed for mature as well as immature human MoDCs (Fig. 3f).

JQ1 inhibits the LPS-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5, ERK1/2, and p38 in human MoDC

To analyze the possible mechanism pathways that mediate the effects of JQ1 on DC phenotype and function, western blot analyses were performed. We found that treatment of human MoDCs with JQ1 inhibited the LPS-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5, ERK1/2, and p38 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

JQ1 inhibits the LPS-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5, ERK1/2, and p38. Human monocytes cultured under DC-driving conditions with final LPS stimulation were exposed to different concentrations of JQ1 (100 and 200 nM) or DMSO throughout the differentiation period. Cellular protein was detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot. The blot was probed with monoclonal antibodies against STAT5B, ERK1/2, p38, and GAPDH as loading control. The phosphorylation state of STAT5B, ERK1/2, and p38 was examined using phospho-specific antibodies

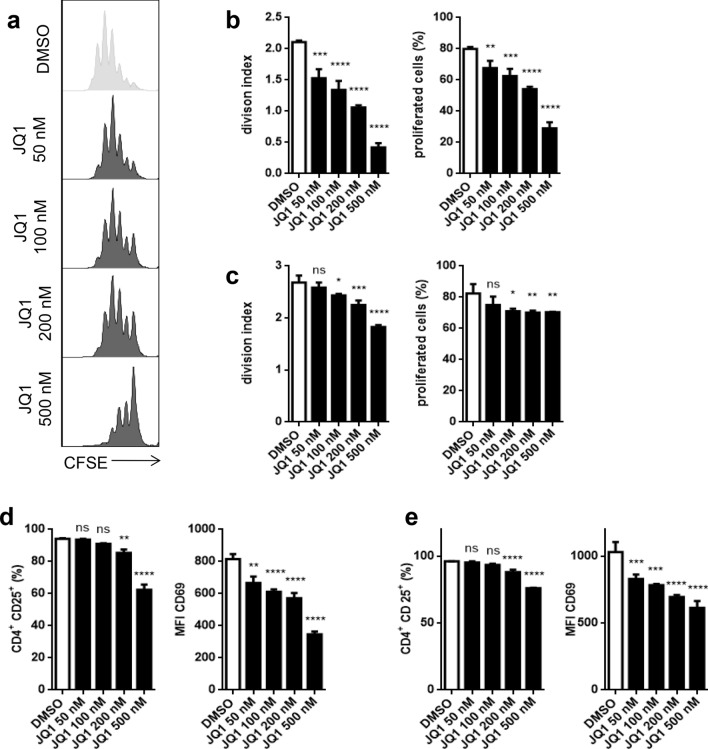

JQ1 reduces murine DC-induced antigen-specific T-cell responses

We analyzed the effect of JQ1 on antigen-specific T-cell responses of both CD4+ and CD8+ cells. We used OT I and OT II cells that express a transgenic T-cell receptor (TCR) against OVA peptides. Splenic murine DCs were treated with JQ1 before loading with OVA with naïve T cells added to a coculture after 24 h. We observed a significantly reduced proliferation of CD4+ (Fig. 5a, b) and CD8+ (Fig. 6a) T cells. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells remain in a more naïve state as T-cell activation markers CD25 and CD69 were less expressed under JQ1 treatment (Fig. 5d), which also applies to CD8+ cells, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 6c). Remarkably, JQ1 induces a strong dose-dependent reduction of intracellular interferon gamma (INFγ) in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6c, d).

Fig. 5.

JQ1 impairs DC-driven antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation and activation. a, b, d CFSE-stained OVA-specific CD4+ T cells from OT II mice were cultured with OVA-primed DCs under varying doses of JQ (50, 100, 200, and 500 nM) for 48 h. a Exemplary histograms of CFSE staining. b Division index and proportion of proliferated CD4+ T cells in coculture with DCs. d Expression of CD4+ T-cell activation markers CD25 and CD69 in coculture with DCs. c, e CD4+ T cells were cultured on a CD3/CD28-covered plate for 48 h. c CFSE-based division index and proportion of proliferated cells. e Expression of CD25 and CD69. Evaluation of triplicates of a single experiment that is representative for two experiments

Fig. 6.

JQ1 impairs DC-driven antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell proliferation and activation. a, c, d CFSE-stained OVA-specific CD8+ T cells from OT I mice were cultured with OVA-primed DCs under varying doses of JQ1 (50, 100, 200, and 500 nM) for 48 h. a Division index and proportion of proliferated CD8+ T cells in coculture with DCs. c Expression of CD8+ T-cell activation markers CD25 and CD69 as well as intracellular INFγ in coculture with DCs. d Exemplary histograms of intracellular INFγ (b, e) CD8+ T cells were cultured on a CD3/CD28-covered plate for 48 h. b CFSE-based division index and proportion of proliferated cells. e Expression of CD25, CD69, and intracellular INFγ. Evaluation of triplicates of a single experiment that is representative for two experiments

In a second step, we examined the effect of JQ1 on T cells in the absence of DCs. In fact, we observed a similar yet lower effect on proliferation and activation of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5c, e) as well as CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6b, e).

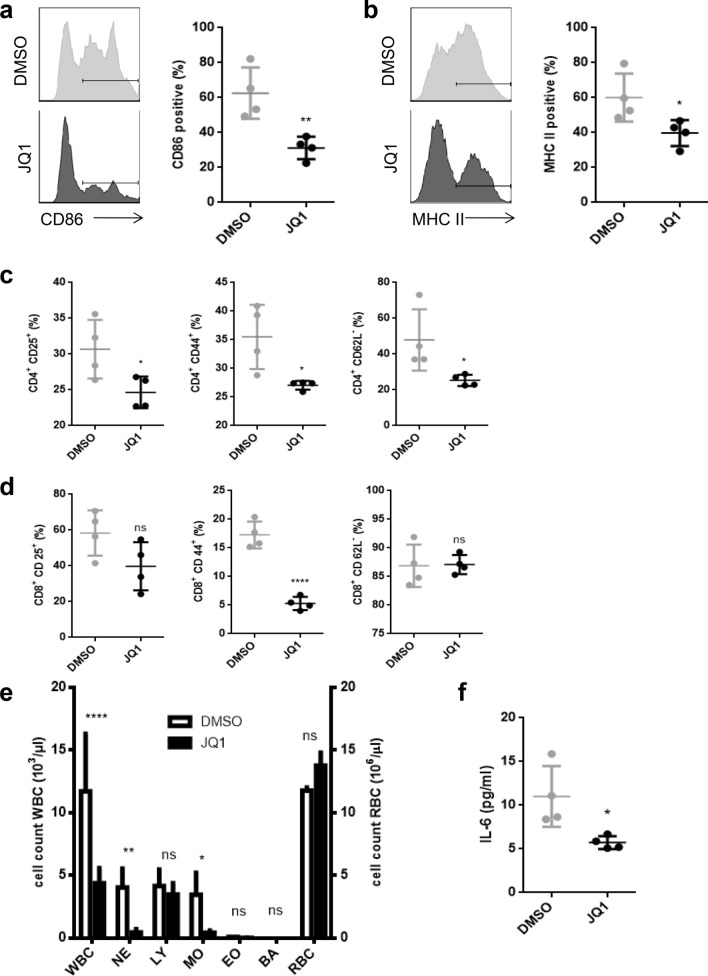

JQ1 suppresses DCs and T-cell activation in vivo

To test the effects of JQ1 in vivo, we used a mouse model based on a LPS-induced endotoxic shock. Mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of (+)-JQ1 at 25 mg/kg body weight [2], respectively, a corresponding dose of DMSO as control. Starting on the second day of treatment, the animals were challenged with LPS (12.5 µg) 3 days in a row. 24 h after the third LPS injection, splenic DCs and T cells as well as peripheral blood were collected and analyzed.

We showed that JQ1 treatment keeps DCs in a more immature phenotype despite being exposed to LPS, based on significantly lower CD86 and MHC class II expression (Fig. 7a, b).

Fig. 7.

JQ1 reduces DC and T-cell immune response in vivo. C57BL/6 mice were treated with 25 mg/kg body weight JQ1 or vehicle for 4 days and challenged with 12.5 µg LPS daily on days 2–4. Analysis of splenic DCs and T cells was done on day 5. Each group was consistent of four individuals. a, b Exemplary histograms and proportion of CD86+, respectively, MHC II+ populations of splenic DCs. c Proportion of CD25+, CD44+, and CD62L- populations of splenic CD4+ T cells. d Proportion of CD25+, CD44+, and CD62L- populations of splenic CD8+ T cells. e Blood count of white and red blood cells. Blood was taken from tail veins. f Serum concentration of IL-6 measured by ELISA

CD4+ T cells are similarly affected as that we observed lower expression of the activation markers CD25 and CD44, while the proportion of CD62L- was significantly higher in the control group, which implies a decreased activation of CD4+ T cells under JQ1 treatment (Fig. 7c).

Concerning CD8+ T cells, we found a relevant decrease in CD44 expression due to JQ1 treatment, while CD25 and CD62L showed no significant difference compared to the control (Fig. 7d).

Furthermore, JQ1 leads to a reduced systemic immune response, as we observed significant differences in peripheral blood cell count of neutrophils, monocytes, and white blood cells in general, while red blood cells were no affected (Fig. 7e). Serum levels of IL-6 were also decreased (Fig. 7f).

Discussion

Inhibition of bromodomains is a promising therapeutic approach in both solid tumors and hematological malignancies and is currently getting evaluated in clinical trials for several cancer entities [1]. It has been previously shown that the impact of BET inhibition is not solely limited on anti-tumorous effects, since the proteins of the BET family are ubiquitously expressed and suppression of immune responses has been reported [1, 27]. Since DCs and especially antigen-specific T cells play a pivotal role in the induction of tumor immunity and immunotherapeutic approaches in cancer [7, 8, 28], we further investigated the role of bromodomains on dendritic cells and T cells, particularly in an antigen-specific context. Our study investigated and further characterized the effect of BET inhibition by JQ1 on DC maturation and activation, as well as the impact of BET inhibition on antigen-specific T-cell responses.

Activation of DCs by pathogens is a deciding step in the general immune response [10]. I-BET151, another BET inhibitor, was shown to oppress the maturation of BMDCs [29, 30]. We show that competitive inhibition of BET bromodomains by the small molecule JQ1 blocks the maturation of murine BMDCs and human MoDCs through a complex variety of DC maturation markers after antigen contact, furthermore, impairs DC activation and DC migratory capacity, while DC antigen uptake appears bromodomain independent.

While it was previously reported that BET inhibition impairs expression of CD80, CD86, and CD83 in human MoDC without relevant downregulation of CD40 and human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) [31], we could, furthermore, observe reduced levels of CD40 as well as MHC class II in murine BMDCs, which is critical for antigen presentation. In addition, we show that production of cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TNF by BMDCs is impaired by BET inhibition. While, in human MoDC, a reduction of IL-10 and IL-12 was also shown, TNF was not affected [31]. Coherent with observations in macrophages [32, 33], IL-6 mRNA expression and cytokine production have been shown to be significantly diminished by BET inhibition. The lesser cytokine production is not due to cell death as the used doses of JQ1 did not reduce cell viability. A possible mechanism of BET inhibition that would mediate restricted DC activation might be due to downregulation of TLR4, which, interestingly, is the case in cardiomyocytes of JQ1-treated rats after acute myocardial infarction [34]. However, downregulation of TLR4 appears not to be the sole mechanism of immunosuppression by BET inhibition, since JQ1-treated mice are also susceptible to TLR4-independent infections like listeria monocytogenes [35].

Furthermore, the effect of BET inhibition by JQ1 was previously shown to be mediated by decreased STAT5 signaling owing to inhibition of LPS-mediated STAT5 phosphorylation [31, 36]. STAT5 is known as crucial transcription factor in maturation process of DCs [37]. Intervention on numerous levels between Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and STAT family proteins, respectively, NF-κB, for example, by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibition or janus kinase (JAK) inhibition, also impairs DC maturation [24, 38]. In addition, we show that JQ1 reduces the phosphorylation of members of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) family ERK1/2 and p38 that play a central role in DC function and activation [39]. Similar findings were previously made in microglia cells as production of proinflammatory cytokines was suppressed by JQ1, possibly due to reduced MAPK phosphorylation [40].

We show that BET inhibition by JQ1 impairs BMDC and MoDC migration in vitro. Since expression of chemokine receptor CCR7 is also reduced by JQ1 in the maturation process, this result was expected, as CCR7 is crucial in CCL19- and CCL21-mediateds migration to draining lymph nodes [41]. Furthermore, it was previously shown that disruption of STAT and NF-κB signaling also impairs migratory activity of DCs [24, 38].

It is known that inhibition of macropinocytosis by amiloride leads to decreased T-cell stimulatory capacity of DCs [42]. We could show that this is not impaired by JQ1 as DCs are still able to take up antigens. However, the previously described increase in macropinocytosis activity after TLR stimulation [13, 14] was reduced 3 h after LPS challenge. Interestingly, 24 h after exposure to LPS, we could still see a trend towards a higher median flow intensity of FITC dextrans in the control group, while, on the other hand, the proportion of not absorbing cells was also slightly higher. We assume that these seemingly contradictory observations are explained by a decrease of micropinocytosis activity in mature DC, as some observed cells in the control group are already fully mature and thus no longer take up antigens, while another part is still in this maturation process. However, since BET inhibition by JQ1 does not affect DC antigen uptake in general but impairs maturation, treated DCs apparently reside in an immature state with baseline levels of antigen processing.

One of the key competences of DCs is the interaction with T cells [9]. As previously shown, JQ1 impairs non-specific human T-cell responses as both proliferation and production of TNF, IL-10, and INFγ in coculture with MoDC is reduced [31]. Furthermore, BET inhibition drives T cells towards anti-inflammatory activity, since the differentiation to TH2- and Treg-subsets is enhanced while TH17-polarization in particular is inhibited [30, 31, 43]. We expanded the previous report and in addition were able to demonstrate in a murine setting that antigen-specific proliferation and maturation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are suppressed by JQ1 treatment. This effect was anticipated considering the previously discussed impact of JQ1 treatment on DC maturation, as CD80-, CD86- or MHC class II-deficient DCs are known to induce anergy in T cells and lead to severe immune disorders [44]. The T cells’ non-active state manifests itself in reduced expression of activation markers CD25 and CD69. We could also observe a similar though minor effect of JQ1 on T cells in a DC-independent setting, which has previously been demonstrated for the BET inhibitor MK-8628 [45]. This observation is expected, since it was already known that STAT signaling is not only vital in DC maturation but also in T-cell proliferation [46]. Interestingly, CD8+ T cells are less affected compared to CD4+ T cells, both in proliferation and activation. Still, we do see a distinct reduction of INFγ production in CD8+ T cells in coculture as well as independent of DCs.

To further transfer the findings into a live setting, we used a simple mouse model in which sepsis was induced by LPS treatment. It is well known that splenic DCs as well as T cells develop a mature phenotype after systemic LPS injection, marked by high expression of CD80, CD86, and MHC class II in case of DCs, while T cells express high CD25 and CD44 and decrease CD62L. We found that JQ1 treatment keeps DCs and CD4+ T cells in an immature phenotype despite LPS challenge, which can be seen as a sign for an overall decreased immune response. Moreover, white blood cells in the peripheral blood count as well as serum levels of IL-6 are significantly lower in the JQ1 treatment group. It was previously shown that BET inhibition reduces the cytokine levels of IL-1, IL-6, IL-12b, and INFγ, and increases survival in the LPS-induced shock model in mice [6, 32].

Because of their physiologic properties, DCs and T cells offer themselves as therapeutic targets for various diseases. DCs and especially antigen-specific T cells play a crucial role in the induction of tumor immunity and immunotherapeutic approaches in cancer [7, 8, 28]. Thus, we apprehend a reduced effectiveness of immunotherapeutic drugs in combination with BET inhibition in cancer therapy, regarding the latter’s immunosuppressive effects. Interestingly, BET inhibition by JQ1 was shown to MYC-independently decrease programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in different mouse and human cancer cell lines and—in contrast to the aforementioned assumption—shows synergistic effects in combination with anti-PD-1 in mice-bearing Eµ-Myc lymphomas [47]. To examine whether the pro- or anti-inflammatory properties of BET inhibition outweigh in combination therapy, further investigation, e.g., in PD-L1 negative cancer cells lines, is needed.

BET inhibitors have entered the clinical evaluation as therapeutics in several cancer entities. Additionally, BET inhibition by JQ1 already offers a more specific therapeutic approach than tyrosine kinase inhibitors and is recognized as a possible therapeutic option for autoimmune diseases [31, 32, 36, 43, 45]. Next to JQ1, we already know several drugs that inhibit the DC’s maturation process and by that suppress their immunogenic function [24, 38]. But also pathogens use this mechanism to successfully escape the immune system [48], so that higher risks of severe infections during BET inhibition are expected and warrant further investigation in the context of immune suppressed cancer patients.

Whereas immunosuppression is the desired effect dealing with autoimmune diseases and graft-versus-host disease, this certain aspect of BET inhibition by JQ1 treatment should closely be monitored when used in cancer therapy. Especially combined treatment of BET inhibitors with other immunomodulatory drugs could lead to a high susceptibility to bacterial or viral infections and may limit the therapeutic applicability in cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- BET

Bromo- and extra-terminal domain

- BMDCs

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

- BRD4

Bromodomain containing protein 4

- CCL

C–C motif chemokine ligand

- CCR

C–C chemokine receptor type

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HLA-DR

Human leukocyte antigen DR

- IL-1

Interleukin-1

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- IL-12

Interleukin-12

- IL-4

Interleukin-4

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- INFγ

Interferon gamma

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- MACS

Magnetic cell separation

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MIP-3β

Macrophage inflammatory protein-3 beta

- MoDCs

Monocyte-derived dendritic cells

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- OVA

Ovalbumin

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

- RT qPCR

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TNFβ

Tumor necrosis factor beta

- β-ME

Beta-mercaptoethanol

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Jens Nolting; methodology: Jens Nolting; formal analysis and investigation: Niklas Remke, Savita Bisht, and Sebastian Oberbeck; writing– original draft preparation: Niklas Remke; writing—review and editing: Jens Nolting and Peter Brossart; funding acquisition: Jens Nolting; supervision: Peter Brossart.

Funding

This study was in part supported by a scholarship awarded to Jens Nolting from Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stifung.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Animal experiments described here comply with Directive 2010/63/EU and were approved by the government of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Mice were maintained according to the guidelines of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (FELASA). The studies were approved by the EC (131/11, 173/09).

Animal source

The strains C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/Crl (OT I Mouse) and C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/Crl (OT II Mouse) were generously provided by J.G. van den Boorn (Dept. of Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Pharmacology, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany). Each strain used in the study was originally supplied by Charles River.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shi X, Liu C, Liu B, Chen J, Wu X, Gong W. JQ1: a novel potential therapeutic target. Pharmazie. 2018;73(9):491–493. doi: 10.1691/ph.2018.8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, Chesi M, Schinzel AC, McKeown MR, Heffernan TP, Vakoc CR, Bergsagel PL, Ghobrial IM, Richardson PG, Young RA, Hahn WC, Anderson KC, Kung AL, Bradner JE, Mitsiades CS. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146(6):904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French CA, Miyoshi I, Aster JC, Kubonishi I, Kroll TG, Dal Cin P, Vargas SO, Perez-Atayde AR, Fletcher JA. BRD4 bromodomain gene rearrangement in aggressive carcinoma with translocation t(15;19) Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):1987–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippakopoulos P, Knapp S. Targeting bromodomains: epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(5):337–356. doi: 10.1038/nrd4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicodeme E, Jeffrey KL, Schaefer U, Beinke S, Dewell S, Chung C-W, Chandwani R, Marazzi I, Wilson P, Coste H, White J, Kirilovsky J, Rice CM, Lora JM, Prinjha RK, Lee K, Tarakhovsky A. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010;468(7327):1119–1123. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):265–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(4):269–281. doi: 10.1038/nri3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994;179(4):1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West MA, Wallin RPA, Matthews SP, Svensson HG, Zaru R, Ljunggren H-G, Prescott AR, Watts C. Enhanced dendritic cell antigen capture via toll-like receptor-induced actin remodeling. Science. 2004;305(5687):1153–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1099153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Platt CD, Ma JK, Chalouni C, Ebersold M, Bou-Reslan H, Carano RAD, Mellman I, Delamarre L. Mature dendritic cells use endocytic receptors to capture and present antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4287–4292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910609107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight SC, Iqball S, Roberts MS, Macatonia S, Bedford PA. Transfer of antigen between dendritic cells in the stimulation of primary T cell proliferation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(5):1636–1644. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1636:AID-IMMU1636>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Chemokines in tissue-specific and microenvironment-specific lymphocyte homing. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12(3):336–341. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(12):984–993. doi: 10.1038/nri1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleman LJ, Berezovskaya A, Grass I, Boussiotis VA. CD28 costimulation mediates T cell expansion via IL-2-independent and IL-2-dependent regulation of cell cycle progression. J Immunol. 2000;164(1):144–151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng J, Montecalvo A, Kane LP. Regulation of NF-kappaB induction by TCR/CD28. Immunol Res. 2011;50(2–3):113–117. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8216-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watts TH. TNF/TNFR family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. T-cell priming by type-1 and type-2 polarized dendritic cells: the concept of a third signal. Immunol Today. 1999;20(12):561–567. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(99)01547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinman RM. The control of immunity and tolerance by dendritic cell. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2003;51(2):59–60. doi: 10.1016/S0369-8114(03)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matheu MP, Sen D, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Generation of bone marrow derived murine dendritic cells for use in 2-photon imaging. J Vis Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heine A, Held SAE, Daecke SN, Wallner S, Yajnanarayana SP, Kurts C, Wolf D, Brossart P. The JAK-inhibitor ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell function in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2013;122(7):1192–1202. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-484642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appel S, Mirakaj V, Bringmann A, Weck MM, Grünebach F, Brossart P. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit toll-like receptor-mediated activation of dendritic cells via the MAP kinase and NF-kappaB pathways. Blood. 2005;106(12):3888–3894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weck MM, Appel S, Werth D, Sinzger C, Bringmann A, Grünebach F, Brossart P. hDectin-1 is involved in uptake and cross-presentation of cellular antigens. Blood. 2008;111(8):4264–4272. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller S, Filippakopoulos P, Knapp S. Bromodomains as therapeutic targets. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1017/s1462399411001992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Wang Y, Toubai T, Oravecz-Wilson K, Liu C, Mathewson N, Wu J, Rossi C, Cummings E, Wu D, Wang S, Reddy P. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. Blood. 2015;125(17):2724–2728. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-598037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schilderink R, Bell M, Reginato E, Patten C, Rioja I, Hilbers FW, Kabala PA, Reedquist KA, Tough DF, Tak PP, Prinjha RK, de Jonge WJ. BET bromodomain inhibition reduces maturation and enhances tolerogenic properties of human and mouse dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toniolo PA, Liu S, Yeh JE, Moraes-Vieira PM, Walker SR, Vafaizadeh V, Barbuto JAM, Frank DA. Inhibiting STAT5 by the BET bromodomain inhibitor JQ1 disrupts human dendritic cell maturation. J Immunol. 2015;194(7):3180–3190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belkina AC, Nikolajczyk BS, Denis GV. BET protein function is required for inflammation: Brd2 genetic disruption and BET inhibitor JQ1 impair mouse macrophage inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3670–3678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng S, Zhang L, Tang Y, Tu Q, Zheng L, Yu L, Murray D, Cheng J, Kim SH, Zhou X, Chen J. BET inhibitor JQ1 blocks inflammation and bone destruction. J Dent Res. 2014;93(7):657–662. doi: 10.1177/0022034514534261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Y, Huang J, Song K. BET protein inhibition mitigates acute myocardial infarction damage in rats via the TLR4/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10(6):2319–2324. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wienerroither S, Rauch I, Rosebrock F, Jamieson AM, Bradner J, Muhar M, Zuber J, Muller M, Decker T. Regulation of NO synthesis, local inflammation, and innate immunity to pathogens by BET family proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(3):415–427. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01353-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu S, Walker SR, Nelson EA, Cerulli R, Xiang M, Toniolo PA, Qi J, Stone RM, Wadleigh M, Bradner JE, Frank DA. Targeting STAT5 in hematologic malignancies through inhibition of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) bromodomain protein BRD2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):1194–1205. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehtonen A, Matikainen S, Miettinen M, Julkunen I. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-induced STAT5 activation and target-gene expression during human monocyte/macrophage differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(3):511–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heine A, Held SAE, Daecke SN, Riethausen K, Kotthoff P, Flores C, Kurts C, Brossart P. The VEGF-receptor inhibitor axitinib impairs dendritic cell phenotype and function. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arrighi JF, Rebsamen M, Rousset F, Kindler V, Hauser C. A critical role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the maturation of human blood-derived dendritic cells induced by lipopolysaccharide, TNF-alpha, and contact sensitizers. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3837–3845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Huang W, Liang M, Shi Y, Zhang C, Li Q, Liu M, Shou Y, Yin H, Zhu X, Sun X, Hu Y, Shen Z. (+)-JQ1 attenuated LPS-induced microglial inflammation via MAPK/NFκB signaling. Cell Biosci. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s13578-018-0258-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(9):2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760:AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Z, Roche PA. Macropinocytosis in phagocytes: regulation of MHC class-II-restricted antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Front Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mele DA, Salmeron A, Ghosh S, Huang H-R, Bryant BM, Lora JM. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses TH17-mediated pathology. J Exp Med. 2013;210(11):2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu F, Li Y, Qian S, Lu L, Chambers FD, Starzl TE, Fung JJ, Thomson AW. Costimulatory molecule-deficient dendritic cell progenitors induce T cell hyporesponsiveness in vitro and prolong the survival of vascularized cardiac allografts. Transpl Proc. 1997;29(1–2):1310. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(96)00532-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Georgiev P, Wang Y, Muise ES, Bandi ML, Blumenschein W, Sathe M, Pinheiro EM, Shumway SD. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses human T cell function. Immunohorizons. 2019;3(7):294–305. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.1900037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaplan MH, Daniel C, Schindler U, Grusby MJ. Stat proteins control lymphocyte proliferation by regulating p27Kip1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(4):1996–2003. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.4.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hogg SJ, Vervoort SJ, Deswal S, Ott CJ, Li J, Cluse LA, Beavis PA, Darcy PK, Martin BP, Spencer A, Traunbauer AK, Sadovnik I, Bauer K, Valent P, Bradner JE, Zuber J, Shortt J, Johnstone RW. BET-bromodomain inhibitors engage the host immune system and regulate expression of the immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1. Cell Rep. 2017;18(9):2162–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salio M, Cella M, Suter M, Lanzavecchia A. Inhibition of dendritic cell maturation by herpes simplex virus. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(10):3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3245:AID-IMMU3245>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.