Abstract

Background

Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with a PD-L1 tumour proportion score ≥ 50% can be treated with pembrolizumab alone. Our aim was to assess the impact of baseline tumour size (BTS) on overall survival (OS) in NSCLC patients treated with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy.

Methods

This retrospective, multicentre study included all patients with untreated advanced NSCLC receiving either pembrolizumab (PD-L1 ≥ 50%) or platinum-based chemotherapy (any PD-L1). The primary endpoint was the impact of BTS (defined as the sum of the dimensions of baseline target lesions according to RECIST v1.1 criteria) on OS.

Results

Between 09–2016 and 06–2020, 188 patients were included, 96 in the pembrolizumab (P-group) and 92 in the chemotherapy group (CT-group). The median follow-up was 26.9 months (range 0.13–37.91) and 44.4 months (range 0.23–48.62), respectively, while the median BTS was similar, 85.5 mm (IQR 57.2–113.2) and 86.0 mm (IQR 53.0–108.5), respectively (p = 0.42). The median P-group OS was 18.2 months [95% CI 12.2–not reached (NR)] for BTS > 86 mm versus NR (95% CI 27.2–NR) for BTS ≤ 86 mm (p = 0.0026). A high BTS was associated with a shorter OS in univariate analyses (p = 0.009) as well as after adjustment on confounding factors (HR 2.16, [95% CI 1.01–4.65], p = 0.048). The CT-group OS was not statistically different between low and high BTS patients, in univariate and multivariate analyses (p = 0.411).

Conclusions

After adjustment on major baseline clinical prognostic factors, BTS was an independent prognostic factor for OS in PD-L1 ≥ 50% advanced NSCLC patients treated first-line with pembrolizumab.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-021-03108-x.

Keywords: Baseline tumour size, Non-small cell lung cancer, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Pembrolizumab

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have profoundly changed the treatment paradigm in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Prior to the use of ICIs, the 5-year survival rate for advanced NSCLC patients was approximately 5% [1]. The KEYNOTE-024 study demonstrated that patients with advanced NSCLC with a high (≥ 50%) PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) tumour proportion score (TPS) benefited from pembrolizumab, with a median overall survival (OS) of 26.3 months versus 13.4 months with chemotherapy (HR = 0.62) [2][2]. Thus, single-agent pembrolizumab has become the standard-of-care regimen for first-line treatment in this selected population [3][3]. However, despite the success of ICIs in a subset of NSCLC patients, some patients still progress and die in a relatively short period of time. A major challenge remains being able to identify which patients will respond favourably to ICI monotherapy. The prognostic and predictive impacts of baseline clinical factors (such as age, gender, performance status (PS), co-morbidities, smoking history, body mass index, and co-medications) and tumour-related factors (such as the sites of metastases or co-mutations) have been studied in order to be able to identify patients who will derive significant benefit from ICIs [5–8]. To date, the only recognized predictive factor is the level of PD-L1 expression on tumour tissue, referred to as the tumour proportion score (TPS) [3][3]. For the subgroup of untreated NSCLC patients with a PD-L1 TPS of ≥ 50%, never having smoked, altered PS, bone and liver metastases have been found to be independent predictors of short OS [7].

Baseline tumour size (BTS) was first identified by retrospective analyses as an independent prognostic factor for OS in advanced melanoma patients treated with pembrolizumab [10]. The impact of BTS on OS in NSCLC patients receiving ICIs has also been evaluated in retrospective studies. To date, studies have been conducted with pretreated patients [11–15] and they have found that a higher tumour burden is associated with a worse survival outcome. The principal objective of the present study was to retrospectively assess the impact of the BTS at diagnosis on OS in patients with advanced NSCLC and a high (≥ 50%) PD-L1 TPS treated first-line with pembrolizumab. The impact of BTS on OS was also evaluated in a parallel cohort of patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy. The secondary objectives were to assess the impact of BTS on progression-free survival and the tumour responses in both cohorts.

Patients and methods

Study design

All patients diagnosed with histologically proven stage IV or unresectable stage III NSCLC who received at least one dose of a first-line systemic therapy were eligible. The patients were treated in one of the following three French hospitals (Nantes University Hospital, Centre Hospitalier Départemental Vendée de La Roche-sur-Yon, and the Clinique Mutualiste de l’Estuaire de Saint-Nazaire). Each patient underwent a baseline full-body CT scan less than eight weeks before the first administration of their treatment. Only patients with measurable disease at baseline as defined by the RECIST v1.1 criteria were included. The patients were assessed every 12–16 weeks by a CT scan according to the local clinical practice. Exclusion criteria were patients with tumours with targetable mutations (e.g. EGFR mutations, ROS1, and ALK translocations), inclusion in clinical trials, concomitant cancer, or stage III disease eligible for curative radio-chemotherapy. The collected data included patient characteristics (age, gender, history of tobacco use, PS, and corticosteroid therapy), tumour characteristics (histology, stage, metastatic sites, and PD-L1 expression), brain metastases treatment during first-line setting, and radiological data (BTS and best overall response).

We studied two groups of patients: those who received platinum-based chemotherapy between September 2016 and November 2019 (CT-group) and those who received pembrolizumab since its regulatory approval in France, between January 2018 and June 2020 (P-group). As recommended by the national and international guidelines, all of the patients in the P-group who received pembrolizumab had a PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50%. Patients in the CT-group received a platinum-based chemotherapy, based on the histology and the patient’s characteristics, irrespective of the level of PD-L1 expression. This retrospective study was conducted before the approval of the combination of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in a first-line advanced setting. This study was conducted in accordance with the local regulations and it was approved by the local independent ethics committee.

Radiological assessments

BTS was quantified by adding the sum of the dimensions of the target lesions according to the RECIST v1.1 criteria [16). A maximum of five target lesions (two per organ) defined by a major axis greater than 10 mm and a pathological lymph node minor axis > 15 mm were recorded by local assessment. If the baseline RECIST v1.1 data had not been established initially, baseline CT scans were reviewed. The overall responses according to the RECIST v1.1 criteria were categorized as either a complete response, a partial response, stable disease, or progressive disease. The objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a complete or partial response. The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a complete or partial response, or stable disease.

Endpoints

In both the CT-group and the P-group, the patients were compared according to their median BTS (above or below the median BTS). The main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of BTS on OS in advanced NSCLC patients treated first-line with pembrolizumab or a platinum-based chemotherapy. OS was defined as the time from the first administration of treatment to the date of death (event) or the last follow-up (censored). The secondary objectives were to evaluate, in both groups, (1) the impact of BTS on PFS, (2) the impact of BTS on ORR and DCR. PFS was defined as the time from the first administration of treatment to progression according to the RECIST v1.1 criteria, death (event), or the last follow-up (censored).

Statistical analysis

The results for the categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. The results for the continuous variables are expressed as means ± the Standard deviation (SD) or, if the variables were not normally distributed, as medians [Interquartile range (IQR)]. Missing data are specified for each variable. P-values for each variable were computed using the Chi2 test or Fisher’s exact test as indicated with an (a) for the categorical variables and Student’s test for the continuous variables. The survival analysis was carried out using the Kaplan–Meier method with a log-rank test (for univariate analysis) and a Cox model. The multivariate Cox model analysis used downward selection with the Akaike information criteria, [17] while systematically retaining well-known associated factors in the analysis. Tests associated with a p-value of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Patients who received at least one dose of platinum-based chemotherapy were included between September 2016 and November 2019 (CT-group) and those who received pembrolizumab between January 2018 and June 2020 (P-group). For both groups, the date for the data cut-off was 26 March 2021, and the follow-up was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. The statistical analyses were performed with R 3.6.1 (2019–07-05) software.

Results

Patient characteristics

All up, 188 patients were included, with 92 receiving a platinum-based chemotherapy (CT-group) and 96 receiving pembrolizumab (P-group) (Suppl. Table 1). The median age was 63 years in both groups. Most of the patients were male (67.7% in the P-group and 60.9% in the CT-group), had a PS of 0–1 (77.9% in the P-group and 68.4% in the CT-group) and a non-squamous histology (80.2% in the P-group and 83.7% in the CT-group). More patients in the P-group had stage III disease compared to the CT-group (24.0% vs. 6.5%, respectively, p < 0.01). The proportion of patients with brain metastases was similar (p = 0.32). More patients were treated with corticosteroids at baseline in the CT-group than in the P-group (39.1% vs. 1.0%, respectively, p < 0.01).

The median BTS (IQR) was similar in both groups, at 85.5 mm (range 53.0–108.5) in the P-group and 86 mm (range 57.2–113.2) in the CT-group (p = 0.42). The characteristics of the patients in both groups according to the cut-off median BTS (86 mm) are presented in Table 1. Clinical variables such as age, PS, corticosteroid therapy, or smoking status did not differ between the high and the low BTS patients in each group. For the patients treated with chemotherapy, liver and brain metastases were significantly more frequent among patients with a BTS greater than the median (44.4% vs. 10.6%, p < 0.01 and 46.7% vs. 23.4%, p = 0.03, respectively). For the patients who received pembrolizumab, those with a BTS greater than the median were more often male (80.4% vs. 56.0%, p = 0.02). There were no significant differences between the stage, the site of metastases, and PD-L1 expression between the high and the low BTS patients (p = 0.72).

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics at baseline in the chemotherapy group and the pembrolizumab group according to the BTS. (a) Categorical variables

| Chemotherapy group n (%) |

Pembrolizumab group n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTS ≤ 86 mm | BTS > 86 mm | p-value | BTS ≤ 86 mm | BTS > 86 mm | p-value | |

| Number of patients | 47 | 45 | 50 | 46 | ||

| Age in years (median, range) | 65 (34–83) | 61 (35–76) | 0.18 | 63 (38–89) | 63 (46–88) | 0.61 |

| Male gender | 28 (59.6) | 28 (62.2) | 0.96 | 28 (56.0) | 37 (80.4) | 0.02 |

| Female gender | 19 (40.4) | 17 (37.8) | 22 (44.0) | 9 (19.6) | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.4) | 0.57 (a) | 3 (6.2) | 1 (2.3) | 0.62 (a) |

| Former | 33 (70.2) | 27 (60.0) | 32 (66.7) | 27 (62.8) | ||

| Current | 13 (27.7) | 16 (35.6) | 13 (27.1) | 15 (34.9) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | ||

| PS | ||||||

| 0—1 | 31 (77.5) | 21 (58.3) | 0.12 | 36 (80) | 31 (75.6) | 0.82 |

| ≥ 2 | 9 (22.5) | 15 (41.7) | 9 (20) | 10 (24.4) | ||

| Missing | 7 | 9 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Histology | ||||||

| Non-squamous | 39 (83.0) | 38 (84.4) | 1.00 | 44 (88.0) | 33 (71.7) | 0.08 |

| Squamous | 8 (17.0) | 7 (15.6) | 6 (12.0) | 13 (28.3) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PDL1 ≥ 50% | ||||||

| No | 24 (77.4) | 28 (77.8) | 1 (a) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Yes | 7 (22.6) | 8 (22.2) | 50 (100) | 46 (100) | ||

| Missing | 16 | 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PDL1 | ||||||

| 50–89% | NA | NA | NA | 35 (70) | 30 (65) | 0.72 |

| ≥ 90% | 15 (30) | 16 (35) | ||||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Corticosteroid therapy | ||||||

| None | 27 (57.4) | 26(57.8) | 0.93 (a) | 40 (80.0) | 40 (87.0) | 0.58 (a) |

| ≤ 20 mg | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.4) | 9 (18.0) | 6 (13.0) | ||

| > 20 mg | 19 (40.4) | 17 (37.8) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| III | 4 (8.5) | 2 (4.4) | 0.68 (a) | 13 (26.0) | 10 (21.7) | 0.8 |

| IV | 43 (91.5) | 43 (95.6) | 37 (74.0) | 36 (78.3) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Brain metastases | ||||||

| No | 36 (76.6) | 24 (53.3) | 0.03 | 34 (68.0) | 36 (78.3) | 0.37 |

| Yes | 11 (23.4) | 21 (46.7) | 16 (32.0) | 10 (21.7) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lung metastases | ||||||

| No | 32 (68.1) | 24 (53.3) | 0.21 | 35 (70.0) | 27 (58.7) | 0.35 |

| Yes | 15 (31.9) | 21 (46.7) | 15 (30.0) | 19 (41.3) | ||

| Missing | ||||||

| Effusion metastases (pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal) | ||||||

| No | 37 (78.7) | 37 (82.2) | 0.87 | 44 (88.0) | 34 (73.9) | 0.13 |

| Yes | 10 (21.3) | 8 (17.8) | 6 (12.0) | 12 (26.1) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Liver metastases | ||||||

| No | 42 (89.4) | 25 (55.6) | < 0.01 | 44 (88.0) | 33 (71.7) | 0.08 |

| Yes | 5 (10.6) | 20 (44.4) | 6 (12.0) | 13 (28.3) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Adrenal metastases | ||||||

| No | 37 (78.7) | 27 (60.0) | 0.08 | 39 (78.0) | 37 (80.4) | 0.63 |

| Yes | 10 (21.3) | 18 (40.0) | 10 (20.0) | 9 (19.6) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Bone metastases | ||||||

| No | 21 (44.7) | 26 (57.8) | 0.29 | 40 (80.0) | 33 (71.7) | 0.48 |

| Yes | 26 (55.3) | 19 (42.2) | 10 (20.0) | 13 (28.3) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Brain metastases treatment | ||||||

| Observation | 1 (9.0) | 3 (14.3) | 0.58 (a) | 5 (31.2) | 1 (10.0) | 0.29 (a) |

| Stereotactic radiotherapy | 4 (36.3) | 4 (19.0) | 6 (37.5) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Whole-brain radiotherapy | 6 (54.5) | 14(66.7) | 5 (31.2) | 6 (60.0) | ||

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the baseline clinical factors associated with OS

We then analysed which factors were associated with OS in both groups (Table 2). In the P-group, altered PS ≥ 2 (p < 0.001), age (p = 0.011), female gender (p = 0.03), liver metastases (p = 0.024), and a BTS greater than the median (p = 0.009) were significantly associated with a shorter OS in univariate analysis. Of these factors, three remained independently associated with a shorter OS in multivariate analysis: altered PS ≥ 2 (HR = 4.52, 95% CI 2.25–9.06, p < 0.001), age as a continuous variable (HR = 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.09, p = 0.002), and a BTS greater than the median (HR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.01–4.65, p = 0.048).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the baseline clinical factors associated with overall survival for each group

| Chemotherapy group | Pembrolizumab group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| PS (≥ 2 vs. < 2) | 1.47 | [0.87;2.49] | 0.153 | 1.32 | [0.74;2.37] | 0.347 | 4.71 | [2.42;9.18] | < 0.001 | 4.52 | [2.25;9.06] | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.005 | [0.98;1.03] | 0.699 | 1.01 | [0.977;1.03] | 0.827 | 1.04 | [1.01;1.07] | 0.011 | 1.05 | [1.02;1.09] | 0.002 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.703 | [0.43;1.14] | 0.155 | 0.667 | [0.40;1.10] | 0.114 | 2.38 | [1.09;5.22] | 0.03 | 1.45 | [0.60;3.55] | 0.411 |

| Stage (IV vs. III) | 0.519 | [0.222;1.212] | 0.13 | 0.385 | [0.16;0.94] | 0.036 | 1.79 | [0.79;4.08] | 0.165 | 1.96 | [0.78;4.92] | 0.15 |

| Brain metastases (Yes vs. No) | 1.276 | [0.77;2.10] | 0.338 | – | – | – | 0.74 | [0.35;1.56] | 0.43 | – | – | – |

| Liver metastases (Yes vs. No) | 1.651 | [0.97;2.80] | 0.064 | 1.55 | [0.87;2.77] | 0.138 | 2.31 | [1.11;4.80] | 0.024 | 1.26 | [0.56;2.82] | 0.569 |

| BTS (> 86 mm vs. ≤ 86 mm) | 1.476 | [0.905;2.409] | 0.119 | 1.27 | [0.75;2.16] | 0.378 | 2.46 | [1.25;4.81] | 0.009 | 2.16 | [1.01;4.65] | 0.048 |

Bold values are the statistical significant values

In the CT-group, none of the analysed variables were associated with OS, neither in univariate nor in multivariate analyses (Table 2). When we excluded stage in the model, because only six patients had stage III disease, results were similar (data not shown). The BTS was not associated with OS in univariate or multivariate analysis (HR = 1.27, 95%CI 0.75–2.16, p = 0.378).

Impact of BTS on survival outcomes

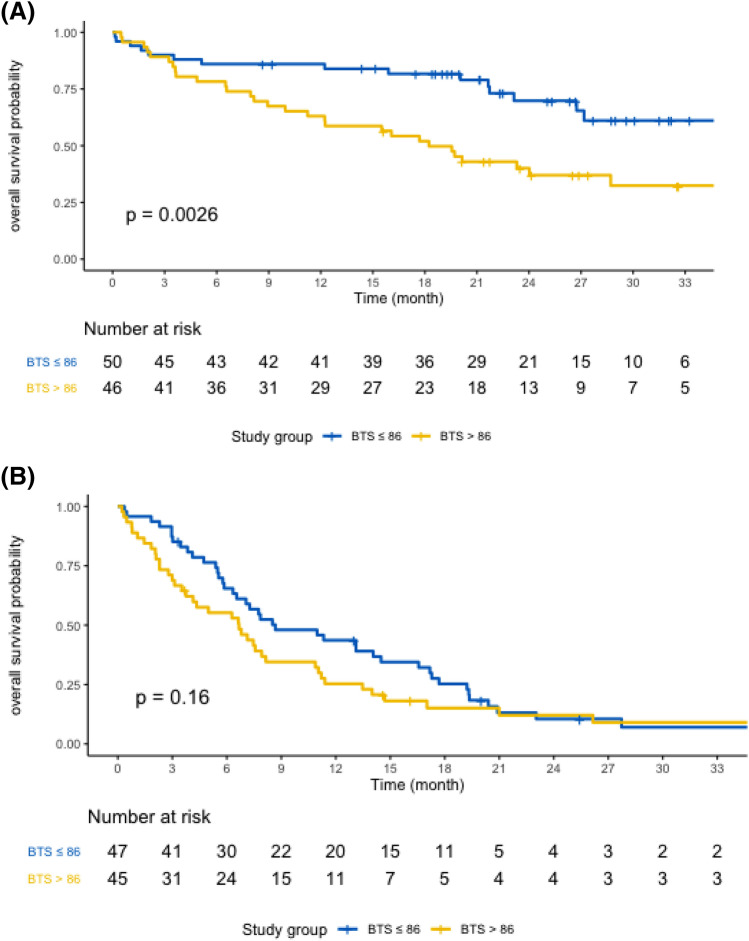

In the P-group, after a median follow-up of 26.9 months (range 0.13–37.91), the median OS was 27.2 months [95% CI 21.7– not reached (NR)]. The median OS was 18.2 months (95% CI 12.2–NR) for patients with a BTS > 86 mm vs. NR (95% CI 27.2–NR) for patients with a BTS ≤ 86 mm (p = 0.0026) (Fig. 1A). At 24 months, 69.8% (95% CI 56.9–85.6) of the patients with a BTS ≤ 86 mm were alive vs. 40.1% (95% CI 27.9–57.6) of those with a BTS > 86 mm (p < 0.0001). In the CT-group, after a median follow-up of 44.4 months (range 0.23–48.62), the median OS was 7.5 months (95% CI 6.3–11.0). No difference was observed according to the BTS (Fig. 1B). The median OS was 8.7 months (95% CI 6.5–16.6) for the patients with a BTS ≤ 86 mm and 6.7 months (95% CI 3.7–10.9) for the patients with a BTS > 86 mm (p = 0.16). At 24 months, 10.5% (95% CI 4.3–25.6) of the patients were alive with a BTS ≤ 86 mm vs. 12.1% (95% CI 5.2–28.3) of those with a BTS > 86 mm (p = 0.65).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier OS of patients with a BTS > 86 mm or a BTS ≤ 86 mm treated with pembrolizumab (A) or chemotherapy (B)

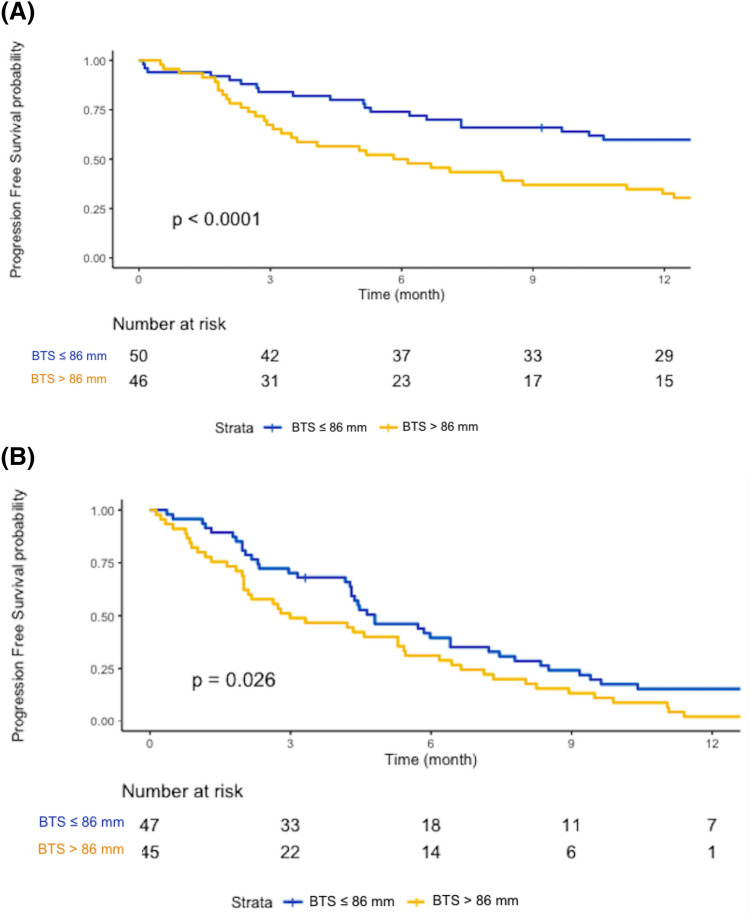

The median PFS was 10.3 months (95% CI 6.7–17.8) for the patients in the P-group and 4.4 months for those in the CT-group (95% CI 3.1–5.7). The patients treated with pembrolizumab who had a high BTS had a shorter PFS of 5.9 months (95% CI 3.5–12.0) vs. 22.1 months for those with a low BTS (95% CI 10.3–NR) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). In the CT-group, the median PFS was slightly shorter for the patients with a high BTS compared to those with a low BTS, at 3.0 months (95% CI 2.0–5.4) vs. 4.8 months (95% CI 4.3–7.2), (p = 0.026) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier PFS of patients with a BTS > 86 mm or a BTS ≤ 86 mm treated with pembrolizumab (A) or chemotherapy (B)

Impact of BTS on ORR and DCR

The ORR was 59.4% for the patients who received pembrolizumab, and it was 16.3% for the patients who received chemotherapy (Table 3). There were no differences between high and low BTS in terms of the ORR and DCR in both groups. For the patients in the P-group, the ORR was 62% for those with a BTS ≤ 86 mm and 57% for those with a BTS > 86 mm group (p = 0.74), while the DCR was 82% and 67.4%, respectively, (p = 0.16).

Table 3.

Tumour responses based on RECIST v1.1 criteria according to the baseline tumour size for each group

| Overall, n (%) | BTS ≤ 86 mm, n (%) |

BTS > 86 mm, n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab group | N = 96 | N = 50 | N = 46 | |

| ORR | 57 (59.4) | 31 (62.0) | 26 (56.5) | 0.74 |

| DCR | 72 (75.0) | 41 (82.0) | 31 (67.4) | 0.16 |

| Chemotherapy group | N = 92 | N = 47 | N = 45 | |

| ORR | 15 (16.3) | 8 (17.0) | 7 (15.6) | 1 |

| DCR | 55 (59.8) | 31 (66.0) | 24 (53.3) | 0.31 |

Discussion

Identification of predictive factors of the response or resistance to ICIs is greatly needed in order to be able to better select which patients are likely to benefit from this first-line therapeutic option. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the prognostic impact of BTS in advanced NSCLC patients with a PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% treated with pembrolizumab as first-line therapy. We found that BTS was an independent prognostic factor for OS in this population, after adjustment on other major clinical prognostic factors (HR = 2.16, p = 0.048). Indeed, a high BTS was independently associated with a shorter OS (18.2 months vs. NR, p = 0.0026). Nearly 70% of patients with a low BTS at diagnosis who received pembrolizumab were still alive after two years, versus 40% of patients with a BTS greater than the median. Conversely, the BTS was not associated with OS in patients receiving first-line chemotherapy, both in univariate and multivariate analyses. These results are consistent with previous retrospective studies that investigated the prognostic impact of BTS in patients with pretreated NSCLC or melanoma treated with ICIs, or various solid tumours treated with experimental immunotherapies in phase I trials [10][10]. So far, no prospective study has evaluated the association of BTS with survival outcomes in NSCLC. The largest study to date regarding NSCLC was a pooled analysis of four clinical trials and 1,461 patients treated with atezolizumab (mostly in later lines of systemic therapy, irrespective of the level of PDL1 expression) [18]. BTS was identified as being significantly associated with OS (HR = 1.64 [1.41–1.91], P < 0.001) and PFS (HR = 1.21 [1.07–1.38], P = 0.003) on multivariate analyses [18].

We believe that this association is clinically relevant, as radiological measurement of the BTS could be a readily applicable tool in clinical practice. However, the methods for calculating tumour burden in lung cancer are diverse, with no gold standard to date, thus making cross-comparisons between trials difficult. We chose to apply the same criteria as previously published, which take into account up to five target lesions [11][11]. A number of studies have added up to ten target lesions in order to improve the accuracy [10][10]. We used RECIST criteria based on the measure of five target lesions, as it is the most validated and commonly used radiological measure in clinical practice. Some authors have used different statistical methods to establish a BTS threshold. Katsurada et al. established a BTS threshold based on a biostatistical tool called Cut-off Finder, whereas Sakata et al. determined the cut-off level by using a receiver operating ROC analysis [12][12]. Others have evaluated the tumour burden as a continuous variable, and they confirmed a linear relationship between BTS and clinical outcome, i.e. the higher the BTS, the poorer the outcome in terms of survival [11][11]. Tarantino et al. analysed BTS and tumour total burden (TTB, defined as the sum of all measurable baseline lesions) by quartiles. They found a good correlation for both BTS and TTB, and a similar impact on survival outcomes [11]. Further studies comparing radiological methods to assess global tumour burden are needed. Despite disparities related to BTS measurement and thresholds, all of the above studies showed a significant negative association between BTS and survival outcomes in NSCLC. It is important to highlight that in our study the median BTS was similar for the chemotherapy and immunotherapy groups (86 mm), and it was close to values used in the other studies mentioned above (for example, the median BTS was 78 mm in the study by Miyawaki et al. involving 163 patients) [14].

In our study, the sites of metastases did not differ between high and low BTS for patients who received pembrolizumab. Moreover, liver and brain metastases were not found to be associated with survival outcomes. For the patients in the P-group with brain metastases, there were no differences regarding local treatment (stereotactic radiotherapy or whole-brain) according to the BTS. However, a limit in our study is that the total number of metastatic lesions was missing. Importantly, a methodological limitation of BTS is the lack of distinction between a large locally advanced tumour mass, an oligo-metastatic disease with few sites involved, and multiple small metastases involving several organs. That is, considering only BTS, it is not possible to distinguish distinct clinical presentation. However, it is now well established that the biology of the disease could be different between localized, oligo-metastatic, and widespread systemic disease [19]. This could impact prognostic and therapeutic strategies, regardless of tumour burden. For example, oligo-metastatic disease is suspected to have indolent course, a better prognosis and therefore could be considered for radical multimodality treatment [20, 21]. Moreover, BTS requires the target lesions to be measurable. Thus, it cannot be applied for patients with only non-measurable disease, such as metastatic pleural effusion or carcinomatous meningitis. A retrospective study estimated the tumour burden using the baseline number of metastatic lesions (BNMLs, including non-measurable lesions) and the baseline sum of the major axis of the target lesions (i.e. the BTS) based on the RECIST criteria [14]. Patients with both a low BTS and BNLM had better survival outcomes, in a population of NSCLC patients who had received ICI monotherapy. In the subgroup of patients with a high (≥ 50%) PD-L1 TPS (n = 65 patients), the median PFS was 20.5 months (95% CI 12.6 months–NR) in the low BNML group and 3.8 months (95% CI 2.0–7.5 months) in the high BNML group, which is very similar to our results.

The median OS was 27.2 months for the P-group patients, which is consistent with the 26.3 months reported in the KEYNOTE-024 study [2]. Furthermore, the median PFS was 10.3 months in our study, which is similar to that reported in the KEYNOTE-024 study [3]. However, the ORR was higher in our study, 59.3% vs. 44.8% in the KEYNOTE-024 study. This rate is close to the 53.7% observed in the PEMBREIZH study, which evaluated pembrolizumab in a real-life cohort [22]. We observed no differences in the ORR between low and high BTS. This is concordant with other retrospective studies of NSCLC patients receiving ICIs, with no difference in the response rates according to the tumour burden [12][12]. Clearly, a degree of caution is required, however, when interpreting these PFS and response rate results due to the lack of a radiological centralized review. By contrast, a study of melanoma patients has reported a significantly higher response rate in patients with a lower BTS [10]. A study published by Huang et al. estimated the antigen burden using all measurable tumour lesions on the pretreatment CT scans of melanoma patients receiving ICIs [23]. It is now well known that CD8+ T cells can become dysfunctional or exhausted, thus failing to eradicate tumours [24]. ICIs can partially reinvigorate exhausted T cells, thereby leading to anti-tumoral effects. It has been suggested that there is a relationship between T cell reinvigoration and tumour burden, with the magnitude of reinvigoration of circulating exhausting T cells determined in relation to the pretreatment tumour burden correlating with the clinical response. Thus, the impact of BTS on the response rate in NSCLC patients remains unclear and will need to be prospectively evaluated.

Advantages of our real-word study were the inclusion of patients with altered PS > 1 and with corticosteroid therapy, usually excluded from clinical trials. This could explain why we observed a median OS of just 7.5 months in the CT-group, which is shorter than the median OS described in the literature of approximately 10–13 months in real-life cohorts and randomized studies [25][25][25][25]. Conversely, the median OS in the P-group found in our study, 27.2 months, was very similar to the median OS observed in clinical trials. The present study had several limitations. Retrospective studies can be affected by errors in recording data and failure to collect information regarding certain items. As CT scans can be performed inconsistently due to differences in local practices, we preferred OS over PFS as the primary endpoint. Moreover, there is a lack of centralized imaging review. As previously discussed, the number of metastatic lesions was not available.

Pembrolizumab alone was the recommended first-line treatment for NSCLC patients with a PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% when this study was conducted. Prior to the availability of pembrolizumab in January 2018, platinum-based chemotherapy was the standard of care irrespective of the level of PD-L1 expression. Recently, the KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407 trials have shown that the combination of chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab improves survival outcomes compared to chemotherapy alone, in both non-squamous and squamous NSCLC, regardless of the level of PD-L1 expression [27][27]. Thus, single-agent pembrolizumab or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy are both first-line standard of care for advanced NSCLC with high (≥ 50%) PD-L1 expression. The current guidelines do not provide clear recommendations on how to choose between ICIs or chemotherapy plus ICIs in this population [4]. Pending the outcomes, physicians are looking for markers of a response or resistance to pembrolizumab. Whether the BTS can stratify NSCLC patients receiving first-line ICIs or chemo-ICI combinations remains unknown and needs to be assessed prospectively.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that BTS at diagnosis had a prognostic impact on OS in NSCLC patients with a PD-L1 TPS ≥ 50% treated with first-line pembrolizumab. Our study provides a rationale for stratifying NSCLC patients treated with front-line ICIs based on tumour burden and for controlling this variable in future clinical trials. Conversely, BTS was not associated with survival outcomes for patients receiving chemotherapy. Whether the best first-line treatment option for NSCLC patients with a high level of tumour PD-L1 expression is single-agent immunotherapy or chemo-immunotherapy combination is a matter of considerable debate. Further studies need to assess whether BTS impacts the efficacy of chemo plus immunotherapy combinations in a first-line setting.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MB, JB did the conception and design of the study and the acquisition of data. MB, TP, TG, JB and EPT did analysis and interpretation of data. MB, EPT draft the article. MB, TC, TP, TG, CG, ALC, RA, EF, JB and EPT did final approval of the version to be submitted.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

In accordance with local regulations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung Cancer 2020. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50% J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(21):2339–2349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv192–iv237. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F, Markovic SN, Molina JR, Halfdanarson TR, Pagliaro LC, Chintakuntlawar AV, et al. Association of Sex, Age, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status With Survival Benefit of Cancer Immunotherapy in Randomized Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012534. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Osta H, Jafri S. Predictors for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(3):189–199. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortellini A, Tiseo M, Banna GL, Cappuzzo F, Aerts JGJV, Barbieri F, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of first-line pembrolizumab effectiveness in patients with advanced NSCLC and a PD-L1 expression of ≥ 50% Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(11):2209–2221. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buti S, Bersanelli M, Perrone F, Tiseo M, Tucci M, Adamo V, et al. Effect of concomitant medications with immune-modulatory properties on the outcomes of patients with advanced cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: development and validation of a novel prognostic index. Eur J Cancer. 2021;142:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doroshow DB, Bhalla S, Beasley MB, Sholl LM, Kerr KM, Gnjatic S, et al. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(6):345–362. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph RW, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Kefford R, Hwu W-J, Wolchok JD, Joshua AM, et al. Baseline Tumor Size Is an Independent Prognostic Factor for Overall Survival in Patients with Melanoma Treated with Pembrolizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(20):4960–4967. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarantino P, Marra A, Gandini S, Minotti M, Pricolo P, Signorelli G, et al. Association between baseline tumour burden and outcome in patients with cancer treated with next-generation immunoncology agents. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsurada M, Nagano T, Tachihara M, Kiriu T, Furukawa K, Koyama K, et al. Baseline Tumor Size as a Predictive and Prognostic Factor of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(2):815–825. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakata Y, Kawamura K, Ichikado K, Shingu N, Yasuda Y, Eguchi Y, et al. Comparisons between tumor burden and other prognostic factors that influence survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(12):2259–2266. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyawaki T, Kenmotsu H, Mori K, Miyawaki E, Mamesaya N, Kawamura T, et al. Association Between Clinical Tumor Burden and Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Monotherapy for Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21(5):e405–e414. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakozaki T, Hosomi Y, Kitadai R, Kitagawa S, Okuma Y. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy for patients with massive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(11):2957–2966. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinze G, Wallisch C, Dunkler D. Variable selection - A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom J. 2018;60(3):431–449. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201700067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins AM, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Rowland A, Sorich MJ. Baseline tumor size and survival outcomes in lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Semin Oncol. 2019;46(4–5):380–384. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belluomini L, Dodi A, Caldart A, Kadrija D, Sposito M, Casali M, et al. A narrative review on tumor microenvironment in oligometastatic and oligoprogressive non-small cell lung cancer: a lot remains to be done. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(7):3369–3384. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentink JF, Paats MS, Dumoulin DW, Cornelissen R, Elbers JBW, Maat APWM, et al. Defining oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer: concept versus biology, a literature review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(7):3329–3338. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-21-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C, Hoang CD, Kesarwala AH, Schrump DS, Guha U, Rajan A. Role of Local Ablative Therapy in Patients with Oligometastatic and Oligoprogressive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer. 2017;12(2):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amrane K, Geier M, Corre R, Léna H, Léveiller G, Gadby F, et al. First-line pembrolizumab for non–small cell lung cancer patients with PD-L1 ≥50% in a multicenter real-life cohort: The PEMBREIZH study. Cancer Med. 2020;9(7):2309–2316. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang AC, Postow MA, Orlowski RJ, Mick R, Bengsch B, Manne S, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2017;545(7652):60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature22079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok TSK, Wu Y-L, Kudaba I, Kowalski DM, Cho BC, Turna HZ, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smit E, Moro-Sibilot D, de Carpeño J, C, Lesniewski-Kmak K, Aerts J, Villatoro R, , et al. Cisplatin and carboplatin-based chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: Analysis from the European FRAME study. Lung Cancer. 2016;92:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadgeel S, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Speranza G, Esteban E, Felip E, Dómine M, et al. Updated Analysis From KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab or Placebo Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum for Previously Untreated Metastatic Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1505–1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paz-Ares L, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Robinson A, Soto Parra H, Mazières J, et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Squamous NSCLC: Protocol-Specified Final Analysis of KEYNOTE-407. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(10):1657–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.