Abstract

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells express high levels of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Cetuximab is an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody that promotes natural killer (NK) cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) via engagement of CD16. We studied safety and efficacy of combining cetuximab with autologous expanded NK cells in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic NPC who had failed at least two prior lines of chemotherapy.

Methods

Seven subjects (six patients) received cetuximab every 3 weeks (six doses maximum) in the pre-trial phase. Autologous NK cells, expanded by co-culture with irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells, were then infused on the day after administration of cetuximab. Primary and secondary objectives were to determine safety of this combination therapy and to assess tumor responses, respectively.

Results

Median NK cell expansion from peripheral blood mononucleated cells after 10 days of culture with K562-mb15-41BBL was 274-fold (range, 36–534, n = 10), and the median expression of CD16 was 98.4% (range, 67.8–99.7%). Skin rash, the commonest side effect of cetuximab in the pre-trial phase, was not exacerbated by NK cell infusion. No intolerable side effects were observed. Stable disease was observed in four subjects and progressive disease in three subjects. Three patients who received NK cells twice had time to disease progression of 12, 13, and 19 months.

Conclusion

NK cells with high ADCC potential can be expanded from patients with heavily pre-treated NPC. The safety profile and encouraging clinical responses observed after combining these cells with cetuximab warrant further studies of this approach. (clinicalTrials.gov NCT02507154, 23/07/2015).

Precis

Engaging NK cell-mediated ADCC using cetuximab plus autologous NK cells in EGFR-positive NPC was well tolerated among heavily pre-treated recurrent NPC. Promising results were observed with 3 out of 7 subjects demonstrating durable stable disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-022-03158-9.

Keywords: NK cell therapy, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, EGFR, Cetuximab, Clinical trial

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common head and neck cancer in South China and Southeast Asia, with up to 30 new reported cases per 100,000 people yearly [1]. Worldwide there are approximately 86,000 cases diagnosed each year and 50,000 deaths attributed to this cancer [1]. Approximately 20% of patients develop locoregional and/or distant relapse despite multimodality treatments, including various combinations of radiation and chemotherapy [2, 3]. Although clinical responses to further treatment have been reported in these patients [4], cancer-specific mortality rate remains high at 70% [5], with poor progression-free survival of 3–5 months and overall survival of 12–15 months [6, 7]. Moreover, repeated treatment with irradiation and chemotherapy has considerable toxicity. For example, in patients with locoregional relapses treated with re-irradiation, serious grade 4 to 5 toxicities (National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE)) were observed in 30% of patients [9, 10]. Therefore, more effective and less toxic treatments are much needed.

One possible immune target in NPC is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a tyrosine kinase receptor whose signals promote cell proliferation and differentiation. Approximately 90% of NPC express high levels of EGFR [11–13] and cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting EGFR, is commonly used for treatment. Cetuximab binding to EGFR abrogates EGF signals [14] and elicits antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) which is primarily exerted by natural killer (NK) cells [15–17]. In patients with cancer, however, NK cells are often functionally impaired [18]. Co-culture of peripheral blood mononucleated cells with a genetically modified K562 cell line expressing membrane-bound interleukin (IL)-15 and 4-1BB ligand (K562-mb15-41BBL) activates NK cells and promotes their expansion [19, 20]. The resulting NK cells have much higher anti-tumor cytotoxicity than unstimulated NK cells [19, 20]. They also express high levels of CD16 (also known as FcγRIII), the receptor that binds the Fc portion of immunoglobulins including cetuximab, and exert powerful ADCC [21]. This method for NK cell expansion has been adapted to current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) conditions [20, 22, 23].

In this study, we document that NK cells with potent ADCC capacity could be expanded from patients with heavily pre-treated recurrent and/or metastatic NPC. We, therefore, assessed the safety and observed the anti-tumor efficacy of administering these cells in combination with cetuximab in this group of patients.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

An open-label phase I clinical trial (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT02507154) was approved by the Singapore Health Science Authority and the Institutional Review Board of the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, Singapore (2014/01320). All procedures were done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical principles in the Belmont Report. Informed written consent was obtained prior to the patients’ inclusion in this study.

Eligible patients were 21 years or older, had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–1, a life expectancy of at least 60 days, a biopsy demonstrating recurrent undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx, and more than 80% EGFR positivity on immunohistochemistry evaluation (supplementary Fig. 1). The recurrent locoregional disease had to be surgically unsalvageable and incurable with re-irradiation or chemotherapy. Patients with recurrent metastatic disease were enrolled only after failing at least two lines of chemotherapy. Patients who received other prior therapies such as anti-PD1 or anti-VEGF were not excluded, but a 30-day or longer interval before enrollment was required. Other inclusion criteria included adequate bone marrow, liver, and kidney function, and at least one recurrent lesion on computed tomography (CT) scan that was measurable using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) criteria [10].

Manufacture of expanded NK cells

All manufacturing procedures were performed under current Good Manufacturing Procedure (cGMP) regulations at Tissue Engineering and Cell Therapy (TECT) facility at National University Health System (NUHS), Singapore. The TECT facility is GMP-certified by Singapore Health Science Authority.

A Master Cell Bank of K562-mb15-41BBL cells for this trial was prepared at the TECT facility. K562-mb15-41BBL cells from the Master Cell Bank were thawed and cultured in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% of fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in G-Rex100M vessels (Wilson Wolf, Saint Paul, MN) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 10 ± 2 days. After the culture, K562-mb15-41BBL cells placed in transfer bags (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) were irradiated at 120 Gy using a linear particle accelerator (Elekta Synergy, Stockholm, Sweden) at the Department of Radiation Oncology, National University Hospital (NUH). The irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells were then cryopreserved in culture medium with 10% DMSO. The absence of cell proliferation of irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL was verified before use for NK cell expansion.

Patients underwent leukapheresis in the apheresis unit at NUH. On the same day, the irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells were thawed and placed into a G-Rex100 vessel (Wilson Wolf) at 3 × 107 cells in 200 mL of SCGM medium (CellGenix, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany). On the following day, peripheral blood mononucleated cells (PBMC) were isolated from the leukapheresis products by ficoll density gradient centrifugation. The immunophenotype of isolated PBMC was analyzed by flow cytometry. The isolated PBMC were suspended in 200 mL of SCGM and added to the G-Rex100 vessel containing irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL. The PBMC concentration was adjusted to achieve 3 × 106 NK cells in 200 mL. Interleukin (IL)-2 (Proleukin; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was added to the cell culture at 40 IU/mL on the date when PBMC were placed, following by every other day to maintain the IL-2 concentration in the culture. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 10 ± 1 day. The sterility of cells in culture was assessed 2 to 4 days before infusion. On the infusion day, cells were collected, washed three times, and then resuspended in saline solution containing 5% human serum albumin. The cell immunophenotype, viability, and residual K562-mb15-41BBL cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The cell volume for infusion was determined based on the results, and then the cells were placed in a transfer bag (Terumo).

Measurement of plasma EBV DNA

Plasma was separated from whole blood by centrifugation. DNA in the plasma was extracted using QIAamp Circulating Nuclei Acid Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed targeting EBV BamH1-W region at a service laboratory (Lucence Diagnostics, Singapore). The limit of detection of plasma EBV DNA was set at 50 IU/mL.

Genotyping of FCGR3A gene

Germline DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononucleated cells using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A fragment of FCGR3A gene, including F158V (rs396991) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was amplified by nested PCR using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The amplified DNA fragment was separated by gel electrophoresis and extracted using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The nucleotide sequence of the purified DNA fragment was determined by Sanger sequencing at a service laboratory (1st Base, Singapore).

Flow cytometry analysis

The immunophenotype of cells before and after culture was analyzed with a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) after staining with anti-CD56 conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD3 allophycocyanin (APC), anti-CD16 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and anti-CD45 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP) (all from BD Biosciences). Cell viability was measured by staining with 7-amino actinomycin (7-AAD; BD Biosciences). As the K562-mb15-41BBL cells express GFP, GFP was used as a marker to ensure that viable K562-mb15-41BBL cells were detectable in the infused NK cell product.

To confirm that the K562-mb15-41BBL cells did not proliferate in vitro after irradiation, an aliquot of the cells was cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 4 or 5 days. After the culture, cells were stained with 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) and FxCycle Violet DNA stain (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the presence of dividing cells was excluded by flow cytometry. In addition to the EdU assay, we also placed irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells into wells of a 96-well plate at 10 to 100 cells per well, and cultured the cells at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3 weeks. Colony formation was assessed with an inverted microscope.

Cytotoxicity assay

Expanded NK cells were co-cultured with target cells (luciferase-labeled EGFR-positive NPC cell line SUNE2) with or without cetuximab (1 µg/mL) for 4 h at various effector-to-target ratios. After culture, BrightGlo (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) was added to the cells and the luminescence from viable target cells was measured using an Flx 800 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Treatment plan

In the trial pre-phase, cetuximab was administrated intravenously at an initial dose of 400 mg/m2, followed by weekly maintenance dose of 250 mg/m2 for 4 to 6 weeks. Patients who did not develop intolerable toxicities after at least four doses of cetuximab in the pre-phase were eligible to continue with the trial (Fig. 1). In the trial phase, cetuximab was administrated at 250 mg/m2 every 3 weeks up to the maximum of six cycles. Expanded NK cells were infused 1 day after cetuximab at cycle 1. The initial NK cell dose in the first three subjects was 1 × 106 NK cells/kg. Subsequently, subjects received 1 × 107 NK cells/kg after safety of the lower dosing was ascertained. To support infused NK cells in vivo, IL-2 was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 1 million units/m2 three times per week for 2 weeks (total of six doses). Patients who achieved objective tumor response or stable disease (SD) after cycle 3 received the second NK cell infusion at cycle 4 with the same subcutaneous IL-2 dosing regimen (total of six doses).

Fig. 1.

Treatment schema. In the pre-phase, cetuximab alone (initial dose 400 mg/m2, maintenance dose 250 mg/m2) was administered weekly intravenously (i.v.). In the trial-phase, cetuximab (250 mg/m2) was administered i.v. at a 3-week cycle up to six cycles. At cycle (C) 1 and 4, NK cells (1 × 106 in the first three subjects or 1 × 107 cells/kg in the later four subjects) were infused i.v. on the day following administration of cetuximab. After NK cell infusion, IL-2 (1 × 106 units/m2) were administered subcutaneously three times per week for 2 weeks. CT scans were performed at the beginning of the pre-phase and the trial-phase, and after cycle 3 and cycle 6, to evaluate treatment response

Treatment evaluation

All subjects underwent routine clinical evaluation, including physical examination, measurement of vital signs, and laboratory tests, including hematologic and biochemical assays, throughout the duration of the study. Adverse events were evaluated using the NCI-CTCAE version 4.0.

Treatment response was assessed using CT scan before the trial phase and after the third and sixth cycles of treatment as per the RECIST v1.1 criteria [10] (Fig. 1). Additional CT scans were scheduled every 6 months or earlier if disease progression was suspected. Complete response (CR) was defined as a complete resolution of the target lesion (as determined by RECIST v1.1) following treatment; partial response (PR) was defined as a reduction of the target lesion by at least 30% from its baseline. Progressive disease (PD) was defined by at least 20% increase of the target lesion and/or development of new metastatic lesion(s). In the absence of PD, SD was defined when neither PR nor CR criteria were met. Treatment response was determined from the start of the pre-trial treatment until the date of last follow-up or date of disease progression (whichever was earlier).

Results

Patient characteristics

Eight subjects (seven patients) were enrolled. One subject died due to rapid disease progression during the pre-phase of this trial, before NK cell infusion. The other seven subjects (six patients) received expanded NK cells in combination with cetuximab. One patient was enrolled twice and received two different NK cell doses with a 12-month interval. Table 1 summarizes the subjects’ characteristics. All were diagnosed with EGFR-positive and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related non-keratinizing undifferentiated carcinoma (WHO type IIB) and had stage IV disease according to the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system at the time of enrollment. Two subjects had recurrent stage IVA disease; one subject had recurrent stage IVB disease; and four subjects had recurrent stage IVC (distant metastases). EBV DNA levels in plasma, which is a marker of disease progression [5], were detected in three subjects (two patients).

Table 1.

Summary of subjects’ characteristics

| Subject number | 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5a | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | M | F | M | M | M | M |

| Age | 58 | 45 | 60 | 66 | 59 | 55 | 63 |

| %NK in PBMCc | 2.9 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 11.5 | 3.3 | 14.5 | 16.2 |

| FCGR3A polymorphism (F158V) | 158 V/V | 158 F/F | 158 F/V | 158 F/V | 158 V/V | 158 F/F | 158 F/F |

| ECOG PSc score | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Stage groupb | IVC | IVC | IVA | IVC | IVC | IVA | IVB |

| Primary tumor category | T0 | T0 | T4b | T0 | T0 | T4b | T0 |

| Regional lymph nodes category | N0 | N0 | N0 | N0 | N0 | N0 | N3 |

| Distant metastasis category | M1 (Widely met) | M1 (OligoMet) | M0 | M1 (OligoMet) | M1 (Widely met) | M0 | M0 |

| Histopathologyd | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated | Non-keratinising undifferentiated |

| Plasma EBVc DNA (IU/mL) | 7.9 × 106 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | 4.7 × 106 | < 50 | 7.5 × 105 |

| LDH (U/L) | 1823 | 386 | 489 | 385 | 2466 | 606 | 486 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.6 | 15 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 10.5 |

| Cetuximab doses in pre-phase | 6 cycles | 4 cycles | 6 cycles | 6 cycles | 6 cycles | 6 cycles | 6 cycles |

| NK cell dose (cells/kg) | 1 × 106, 1 dose | 1 × 106, 1 dose | 1 × 106, 2 doses | 1 × 107, 2 doses | 1 × 107, 1 dose | 1 × 107, 2 doses | 1 × 107, 1 dose |

| Adverse events | Grade 1 Fatigue |

Grade 3 skin toxicity Grade 1 transient dizziness |

Grade 1 Fatigue | Grade 1 Fatigue | Grade 1 Fatigue |

Grade 3 pericardial effusion Grade 2 Dizziness |

Grade 1 transient dizziness |

| Treatment response | PDc | SDc | SD | SD | PD | SD | PD |

aThese subjects were the same patient. The patient was enrolled at a different NK cell dose

bStaging according to the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system

cAbbreviations: PBMC, peripheral blood mononucleated cells; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; PD, progress disease; SD, stable disease

dMore than 80% EGFR positivity on immunohistochemistry evaluation

All subjects had failed at least two lines of prior chemotherapy (median 3, range 3–4), including gemcitabine- and platinum-based chemotherapy. In the pre-phase, subjects received at least four cycles of cetuximab (median 6, range 4–6) with no evidence of response. In the trial-phase, three subjects (three patients) received 1.0 × 106 NK cells/kg and four subjects (four patients) received 1.0 × 107 NK cells/kg. Three subjects received a second NK cell infusion, as they had stable disease after the first NK cell infusion.

NK cell activation and expansion

Ten NK cell products were manufactured by co-culture with irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells. Median percent of NK cells in PBMC isolated prior to culture was 11.5% (range, 2.9%–16.2%; n = 10). After 10 days of culture, the median percent of NK cells rose to 84.2% (range, 56.0%–92.9%) (Fig. 2a) and the median fold expansion was 274 (range, 36–534). NK cell expansion from NPC patients was similar to the one observed with leukapheresis products from 25 healthy donors enrolled in the other trials at our institution during the same period, and in nine of ten products exceeded 200-fold after 10 days (Fig. 2c). All products met both quality control criteria and clinical dose requirements set in the protocol.

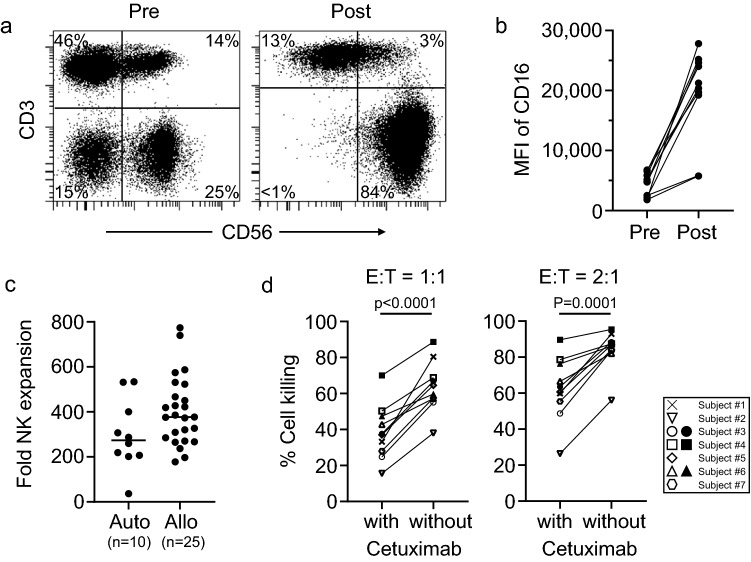

Fig. 2.

Ex vivo NK cell expansion. a Representative flow cytometry dot plots of NK cells before (pre) or after (post) expansion. NK cells in peripheral blood mononucleated cells were co-cultured with irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL for 10 ± 1 days in presence of 40 IU/mL of IL-2. b Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD16 in CD56 + CD3- cells before (pre) and after (post) NK cell expansion. P < 0.0001. c Fold expansion of NK cells after 10 ± 1 day culture in this study (autologous, “Auto”, n = 10) and other studies (allogenic, “Allo”, n = 25). NK cells were expanded under the same condition. P = 0.08 by unpaired t-test. d Killing potency of expanded NK cells. Expanded NK cells were co-cultured with EGFR-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line (SUNE2) with or without cetuximab (1 µg/mL) for 4 h at the indicated effector to target ratio (E:T). P values were calculated by paired t-test

As CD16 on NK cells binds cetuximab-coated NPC tumor cells and triggers NK cell-mediated ADCC [17], we measured expression of CD16 on the expanded NK cells. The median percentage of CD16-positive NK cells before culture was 84.5% (range, 63.7–97.2%) and it rose to 98.4% (range, 67.8–99.7%) after culture (p = 0.025 by paired t-test, n = 10). Similarly, the median mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD16 expression on NK cells was 4,798 (range, 1,819–6,769) before culture, and it rose to 20,811 (range, 5,766–25,182) after culture (p < 0.0001 by paired t-test, n = 10; Fig. 2b).

The mean (± SD) 4-h cytotoxicity of expanded NK cells against the EGFR-positive NPC cell line (SUNE2) in the absence of cetuximab was 62.6% ± 17.5% at 2:1 effector to target (E:T) ratio. Addition of cetuximab (final concentration 1 µg/mL) significantly increased anti-tumor cytotoxicity to 84.3% ± 10.7% (p < 0.0001 by paired t-test; Fig. 2d). Cetuximab alone was not cytotoxic against NPC cells in these cultures (mean cell killing 2.2% ± 2.5%).

The F158V (rs396991) single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of FCGR3A encoding CD16 is associated with different binding affinity for immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) [26, 27]. The homozygous 158 V allele has the highest affinity for IgG1, and its expression correlates with a better response to antibody therapy [17]. This variant was present in two subjects (one patient). The heterozygous variant was present in two subjects, and the homozygous genotype for 158F allele was identified in three subjects (Table 1). We did not observe higher ADCC activities in the subjects with homozygous 158 V in a short-term 4-h cytotoxicity assay.

Treatment toxicity

Infusion of expanded NK cells was generally well tolerated. Neither acute reactions nor grade 4 or 5 adverse events were observed. Adverse events potentially relatable to NK cell infusion with cetuximab are shown in Table 1. Fatigue was the commonest side effect reported during the infusion, with grade 1 fatigue being observed in four subjects. Grade 1 or 2 dizziness was observed three subjects, with no hemodynamic changes in heart rate or blood pressure. These events completely resolved within one day following NK cell infusion and were apparently not associated with the NK cell dosage.

In the pre-trial phase, all patients developed cetuximab-related acneiform rash (grade 1 or 2). In the trial phase, skin toxicity was observed in only one subject who had a grade 1 skin rash in the pre-phase, which worsened to grade 3 skin rash. The skin rash occurred soon after the fourth dose of IL-2 injection following the NK cell infusion. Biopsy of this skin rash did not reveal any NK cell infiltration on immunohistochemistry evaluation, and its pathogenesis was unclear. The rash improved with topical emollient and steroid cream.

One patient who received 1.0 × 107 NK cells/kg developed grade 3 pericardial effusion 5 days after the first NK cell infusion. The effusion fluid was a transudate and no positive microbial cultures or malignant cells were identified on the cytopathological assessment of the fluid. The fluid collection improved after pericardiocentesis, and the patient was discharged 1 day after admission. On follow-up, no re-accumulation of the pericardial effusion was observed. The patient did not have any other complications and had no pericardial effusion after the second NK cell infusion. Notably, the patient also had hypothyroidism due to previous radiation therapy, which might have contributed to the development of the event.

Antitumor responses

Among the seven subjects (six patients), three (two patients) had disease progression with no evidence of response. The remaining four patients had SD. Three received the second NK cell infusion at cycle 4, while one who had grade 3 skin toxicity following the first NK cell infusion declined the second infusion.

In four subjects (three patients) who received one NK cell infusion, the time to disease progression was 3 to 5 months. In contrast, in the other three subjects who received NK cells twice, the time to disease progression was 12, 13, and 19 months (Fig. 3a). All three patients were alive at the last follow-up, at 22 to 32 months later. Notably, one patient had clinical resolution of his pre-existing oculomotor nerve palsy. This patient had stage IVA disease at enrollment, with a tumor localized to his left orbital apex and cavernous sinus resulting in oculomotor nerve palsy. Despite no clear evidence of tumor shrinkage (more than 30% reduction) on CT scan after NK cell infusions (Fig. 3b), there was an obvious clinical improvement of his ptosis (Fig. 3c). After completion of cycle 6, disease remained stable without further treatment until it eventually progressed 19 months later.

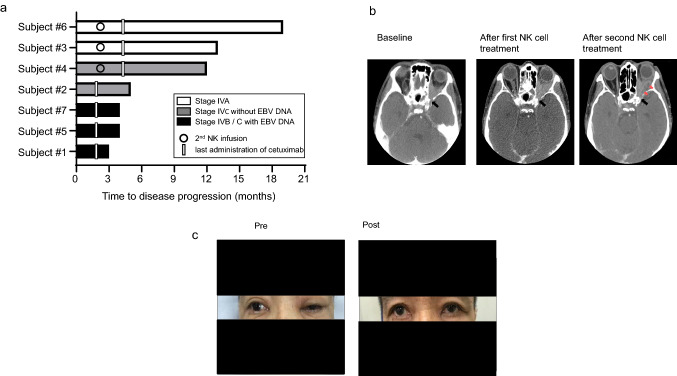

Fig. 3.

Treatment response. a Swimmer plots show the length of time to disease progression of each subject. Subjects with metastatic sites (lymph node or visceral organ, Stage IVB or C) were indicated by gray or black bars. Subjects in whom plasma EB-virus DNA (EBV DNA) was detectable were indicated by black bars. b CT images of subject #6 before (pre) or after (post) the combination therapy. No clear tumor shrinkage (more than 30% reduction) was noted. CT images are captured at the level of the optic nerve canal (black arrow) for consistency of comparison. Areas of radiolucency indicative of tumor necrosis (red arrows) were seen after second NK cell infusion c Clinical pictures of subject #6 before (pre) or after (post) the combination therapy. The ptosis of the left eye by the oculomotor nerve palsy improved after the first NK cell infusion. The written informed consent for his picture being published was received from the patient

In EBV-related NPC, plasma EBV DNA level is an informative prognostic marker [6, 10]. All three subjects with PD had high levels of plasma EBV DNA (> 50 IU/mL) before treatment while in the four subjects with SD, plasma EBV DNA was below the limits of detection.

Discussion

We conducted a phase I clinical trial to assess the safety and anti-tumor potential of combining the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab with activated NK cells in patients with locoregionally relapsed and/or metastatic NPC. Using autologous leukapheresis products and co-culture with irradiated K562-mb15-41BBL cells, large numbers of activated NK cells were obtained under cGMP conditions. Notably, the number of NK cells obtained consistently exceeded the requirement for 1 × 107/kg in the protocol. This was despite the fact that all patients had received multiple courses of chemotherapy prior to leukapheresis. Expression of CD16, the receptor that mediates ADCC, was upregulated during the expansion process, and virtually all NK cells were CD16 positive after culture. Thus, these NK cells are armed to engage ADCC with cetuximab against EGFR-positive NPC.

Previous studies supported the safety of combining cetuximab with chemotherapy or radiation [27–29]. A potential concern prior to our study was that enhancing ADCC could magnify cetuximab toxicities and, hence, prevent the implementation of this treatment strategy. Our results, however, clearly indicate that it is possible to combine cetuximab with NK cells without major adverse effects. NK cells were infused at 1 × 106 cells/kg in the first three subjects and at 1 × 107 cells/kg in the remaining four, with no differences in adverse events observed between dosing schedules, and with no CTCAE grade 4 or 5 toxicities. Grade 3 skin toxicity and grade 3 pericardial effusion were observed in one subject each. These toxicities were most likely attributed to IL-2 injection and hypothyroidism, respectively, rather than NK cell treatment. These toxicities resolved completely with standard medical treatment. All three patients who received NK cells twice had a relatively long time to disease progression (12 months, 13 months, and 19 months); the estimated time for such patients according to the published experience with standard palliative chemotherapy would be in the range of 3–6 months.

The most common variant of NPC in the endemic area is a non-keratinizing subtype related to EBV infection [5]. All subjects’ NPCs in this study were confirmed to be EBV associated with EBV-related small RNA (EBER) expression on chromogenic in situ hybridization. In patients with nasopharyngeal EBV-associated carcinoma, plasma EBV DNA level is an important prognostic indicator [5, 11]. Plasma EBV DNA levels were extremely high (higher than 7.5 × 105 IU/mL) in the three subjects who progressed rapidly after cetuximab plus NK cell therapy. In the remaining four subjects with SD, EBV DNA was not detected in plasma (< 50 IU/mL), suggesting that this parameter might be a predictor of response to the cetuximab–NK cell combination. If so, disease control before treatment would be critical to maximize its effect. Because EBV-related NPC highly expresses EBV latent antigens, such as EBNA-1–3 and LMP1–2 [30], these antigens could potentially be targeted by cytotoxic T lymphocytes or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) [30–35]. The relative advantages and disadvantages of these approaches as compared to the cetuximab–NK cell combination used in this study need to be further elucidated, but potential synergies between T cell and NK cell infusion should be explored. To this end, it is possible that activated NK cells may not only kill tumor cells directly but also favor the expansion of anti-tumor T cells through cytokine secretion and elimination of immune-suppressive cells [25, 36] From a practical standpoint, it is important to note that we were able to prepare large numbers of NK cells with high ADCC activity within 10 days of culture, even from patients who had been heavily pre-treated.

We infused autologous NK cells that were activated in culture and induced to proliferate. Expanded NK cells can also be genetically modified either permanently using viral transduction or transiently using electroporation of mRNA under cGMP conditions [24]. Modifications that can enhance NK cell activity include expression of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) [19, 37], activating receptors [38], cytokines [39], and downregulation of inhibitory receptors [40]. The results of this study suggest that it should be feasible to prepare genetically modified NK cells from patients with NPC. NK cells do not express T cell receptors and, hence, do not cause graft-versus-host disease [25]. This unique property facilitates the generation of allogeneic “off-the-shelf” NK cell products from healthy donors, cord blood, or pluripotent stem cells, which could be used to enhance cetuximab activity on demand [25].

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Liza Ho, Michelle Ng, Hilary Mock, Huai Hui Wong, Lee Hui Chua, Wan Rong Sia, Sally Chai, and Miki Wong for their expert assistance in the preparation of NK cells for infusion; and Serene Siow and Judy Goh for their role as clinical trial coordinators in this study. This work was supported by funding from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore Transitional Award TA/2015/035; and STaR Award STaR/0025/2015.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CAR

Chimeric Antigen Receptor

- cGMP

Current Good Manufacturing Practice

- CR

Complete Response

- CT

Computed Tomography

- EBER

EBV-related small RNA

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- E:T ratio

Effector to Target ratio

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- IL

Interleukin

- MFI

Mean Fluorescence Intensity

- NCI-CTCAE

National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- NK

Natural Killer

- NPC

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononucleated Cells

- PD

Progressive Disease

- PR

Partial Response

- RECIST 1.1

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1

- SD

Stable Disease

- SNP

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism

- TIL

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes

Author contributions

CML, NS, DC, and BCG Conceptualize and design of study protocol, NS, and DC Development of technology used for study, CML, AL, MP, LPK, LKT, KSL, DC, BCG, and NS Patient accrual/data curation, CML, AL, DC, BCG, and NS Formal analysis, CML, DC and BCG Funding acquisition, CML, AL, DC, and NS Writing of manuscript, all authors (CML, AL, MP, LPK, LKT, KSL, BFP, ET, DC, BCG, and NS) Review, editing and approval of final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore Transitional Award TA/2015/035; and STaR Award STaR/0025/2015.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

D Campana: Royalties—Juno Therapeutics; stockholder and consultant—Unum Therapeutics, Nkarta Therapeutics, Medisix Therapeutics; Co-inventor in patent applications for technologies relevant to study. N Shimasaki: Co-inventor in patent applications for technologies relevant to study. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Singapore Health Science Authority and the Institutional Review Board of the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, Singapore (2014/01320). All procedures were done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical principles in the Belmont Report.

Consent to participate

Informed written consent was obtained prior to the patients’ inclusion in this study.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient depicted in Fig. 3 to allow the use of his picture for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mak H, Lee S, Chee J, et al. Clinical Outcome among Nasopharyngeal Cancer Patients in a Multi-Ethnic Society in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riaz N, Sherman E, Lee N. The Importance of Locoregional Therapy in Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1353–1354. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma B, Lim W, Goh B, et al. Antitumor Activity of Nivolumab in Recurrent and Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: An International, Multicenter Study of the Mayo Clinic Phase 2 Consortium (NCI-9742) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(14):1412–1418. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.77.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Chan A, Le Q, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argirion I, Zarins K, Ruterbusch J, et al. Increasing incidence of Epstein-Barr virus–related nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2020;126(1):121–130. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Huang Y, Hong S, et al. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2016;388(10054):1883–1892. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Q, Colevas A, O’Sullivan B, et al. Current Treatment Landscape of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma and Potential Trials Evaluating the Value of Immunotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(7):655–663. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leong Y, Soon Y, Lee K, Wong L, Tham I, Ho F. Long-term outcomes after reirradiation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma with intensity-modulated radiotherapy: a meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40(3):622–631. doi: 10.1002/hed.24993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz L, Litière S, de Vries E et al (2016) RECIST 1.1—Update and clarification: From the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer 62:132–137. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kang H, Kiess A, Chung C. Emerging biomarkers in head and neck cancer in the era of genomics. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(1):11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma B, Poon T, To K, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor angiogenesis, Ki 67, p53 oncoprotein, epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2 receptor protein expression in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma?a prospective study. Head Neck. 2003;25(10):864–872. doi: 10.1002/hed.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua D, Nicholls J, Sham J, Au G (2004) Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor expression in patients with advanced stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol*Biol*Phys 59(1):11–20. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Adams G, Weiner L. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(9):1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott A, Wolchok J, Old L. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon K, Wu J, Walcheck B. Engineering Anti-Tumor Monoclonal Antibodies and Fc Receptors to Enhance ADCC by Human NK Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(2):312. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris R, Jaffee E, Ferrone S. Tumor Antigen-Targeted, Monoclonal Antibody-Based Immunotherapy: Clinical Response, Cellular Immunity, and Immunoescape. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(28):4390–4399. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kono K, Takahashi A, Ichihara F, Sugai H, Fujii H, Matsumoto Y. Impaired Antibody-dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Mediated by Herceptin in Patients with Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5813–5817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106(1):376–383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, et al. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):4010–4017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mimura K, Kamiya T, Shiraishi K, et al. Therapeutic potential of highly cytotoxic natural killer cells for gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(6):1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimasaki N, Coustan-Smith E, Kamiya T, Campana D. Expanded and armed natural killer cells for cancer treatment. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(11):1422–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Shimasaki N, Lim J, et al. Phase I Trial of Expanded, Activated Autologous NK-cell Infusions with Trastuzumab in Patients with HER2-positive Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(17):4494–4502. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimasaki N, Campana D (2020) Engineering of natural killer cells for clinical application. Methods Mol Biol 2020:91–105. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0203-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2020;19(3):200–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koene H, Kleijer M, Algra J, Roos D, E.G.Kr. von dem Borne A, de Haas M (1997) FcγRIIIa-158V/F polymorphism influences the binding of IgG by natural killer cell FcγRIIIa, independently of the FcγRIIIa-48L/R/H phenotype. Blood 90(3):1109–1114. 10.1182/blood.v90.3.1109 [PubMed]

- 27.Taylor R, Chan S, Wood A, et al. FcγRIIIa polymorphisms and cetuximab induced cytotoxicity in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(7):997–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0613-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu T, Ou X, Shen C, Hu C. Cetuximab in combination with chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2016;27(1):66–70. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan A, Hsu M, Goh B, et al. Multicenter, Phase II Study of Cetuximab in Combination With Carboplatin in Patients With Recurrent or Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3568–3576. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.02.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, Tan L, Lim C. Cellular-based immunotherapy in Epstein-Barr virus induced nasopharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018;84:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J, Fogg M, Wirth L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-specific adoptive immunotherapy for recurrent, metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2017;123(14):2642–2650. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chia W, Teo M, Wang W, et al. Adoptive T-cell transfer and chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic and/or locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2014;22(1):132–139. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Louis C, Straathof K, Bollard C, et al. Adoptive transfer of EBV-specific T cells results in sustained clinical responses in patients with locoregional nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33(9):983–990. doi: 10.1097/cji.0b013e3181f3cbf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Comoli P, De Palma R, Siena S, et al. Adoptive transfer of allogeneic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T cells with in vitro antitumor activity boostsLMP2-specific immune response in a patient with EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(1):113–117. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Chen Q, He J, et al. Phase I trial of adoptively transferred tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte immunotherapy following concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(2):e976507. doi: 10.4161/23723556.2014.976507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parihar R, Rivas C, Huynh M, et al. NK cells expressing a chimeric activating receptor eliminate MDSCs and rescue impaired CAR-T cell activity against solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(3):363–375. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.cir-18-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):545–553. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1910607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang Y, Connolly J, Shimasaki N, Mimura K, Kono K, Campana D. A chimeric receptor with NKG2D specificity enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73(6):1777–1786. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imamura M, Shook D, Kamiya T, et al. Autonomous growth and increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells expressing membrane-bound interleukin-15. Blood. 2014;124(7):1081–1088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-556837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamiya T, Seow S, Wong D, Robinson M, Campana D. Blocking expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A overcomes tumor resistance to NK cells. J Clin Investig. 2019;129(5):2094–2106. doi: 10.1172/jci123955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.