Abstract

Radiation therapy (RT) can prime and boost systemic anti-tumor effects via STING activation, resulting in enhanced tumor antigen presentation and antigen recognition by T cells. It is increasingly recognized that optimal anti-tumor immune responses benefit from coordinated cellular (T cell) and humoral (B cell) responses. However, the nature and functional relevance of the RT-induced immune response are controversial, beyond STING signaling, and agonistic interventions are lacking. Here, we show that B and CD4+ T cell accumulation at tumor beds in response to RT precedes the arrival of CD8+ T cells, and both cell types are absolutely required for abrogated tumor growth in non-irradiated tumors. Further, RT induces increased expression of 4-1BB (CD137) in both T and B cells; both in preclinical models and in a cohort of patients with small cell lung cancer treated with thoracic RT. Accordingly, the combination of RT and anti-41BB therapy leads to increased immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment and significant abscopal effects. Thus, 4-1BB therapy enhances radiation-induced tumor-specific immune responses via coordinated B and T cell responses, thereby preventing malignant progression at unirradiated tumor sites. These findings provide a rationale for combining RT and 4-1bb therapy in future clinical trials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-022-03325-y.

Keywords: 4-1BB ligand, Radiotherapy, B-Lymphocytes, Small cell lung carcinoma, Melanoma

Introduction

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA4 has shown impressive gains compared to conventional chemotherapy for some patients with metastatic melanoma [1–3] and lung cancer [4–6]. Trials of TIGIT [7] and other immune checkpoint inhibitors [8] in combination with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint therapies are showing signs that novel combinations of checkpoint inhibitors may improve outcomes even further. Immune costimulatory agonist antibodies represent another class of immune therapies which have shown significant responses in murine models [9–11] although early clinical trials are ongoing with mixed results. These drugs have been demonstrated to impact not only CD8 T cells but also CD4 T cells where they may play an important role in coordinating recruitment and proliferation of B cells and other antigen presenting cells as well as tertiary lymphoid structures and rich humoral responses. The mixed success of many agonist antibodies in early phase clinical trials may be due to poor agonist activity [12] or off target effects/toxicities limiting opportunities for dose escalation [13]. Second-generation co-stimulatory antibodies targeting 41BB may offer more appropriate activation without off target toxicities [9, 14]. Radiotherapy can be considered as a powerful in situ vaccine and may offer an opportunity for combination treatment to further enhance responses to novel immunotherapies. Early studies have reported sporadic ‘abscopal’ effects whereby tumor regression is seen in unirradiated tumor targets following local radiotherapy [15]. Multiple early preclinical studies indicated that this abscopal effect may be result of anti-tumor immune response induced by radiation therapy [16, 17] and that use of radiotherapy with immunotherapy may enhance the abscopal effect [18, 19]. Recently, many clinical trials have sought to combine radiation therapy (RT) with novel immune checkpoint therapies. These studies have met with mixed early results [20–23] and although randomized comparisons to demonstrate synergy are ongoing [24] (NCT03646617, NCT03811002, NCT04081688, NCT02444741), very little is understood about the nature of the RT associated immune response to help guide the design of next generation clinical trials. One major benefit of RT is the localized nature of treatment which allows for targeting of tumor microenvironments while limiting systemic effects. RT has been previously reported as an immune stimulator [25] and has been shown to enhance the diversity of the T cell receptor repertoire and augment the T cell response [26]. In preclinical studies, RT has been shown to mediate tumor regression via adaptor protein stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-mediated cytosolic DNA sensing, with associated Type I interferon and adaptive immune responses [27]. Unfortunately, activation of this same STING/interferon pathway also drives myeloid derived suppressor cell (MDSC) mobilization and associated RT resistance [28]. Studies to evaluate RT with novel costimulatory antibodies have shown evidence of synergy in other preclinical studies [29, 30]. Previous work has demonstrated that RT plus anti-4-1BB combinations are synergistic and have demonstrated improved anti-tumor immune response [31–33]. As is the case with most of the cancer immunotherapy field, much of the focus with RT combination studies has been on CD8 T cells which are demonstrated to play a critical role in effector anti-tumor function [34, 35]. CD8 T cells play a critical role and waves of renewable effector CD8 T cells are likely responsible for successful immune response against cancer [36]. What is not clear however, is how these renewable T cells are maintained and what is the makeup of the other immune cells which refresh and support effector CD8 T response. We know from decades of basic immunology [37, 38] and more recent attention in cancer immunology that CD4 T cells [39] and critically B cells [40, 41] are also important for mounting robust anti-tumor immune response following radiotherapy. In this study, we identified an early influx of CD4 T cells and B cells following flank radiotherapy in a murine model. We show further that these cells are required, along with CD8 T cells, for RT response with immunotherapy targeting 4-1BB agonist therapy.

4-1BB (CD137; TNFRSF9) was initially discovered on T cells [42] and is known to be an activation-induced molecule [43]. In vitro, effects include induction of cell cycle progression, cytokine induction, prevention of activation-induced immune cell death [44], and involvement in reshaping T cell metabolism [45, 46]. In vivo, 4-1BB activation has been demonstrated as an important part of CD8 T cell robust anti-tumor immune response [47, 48]. Indeed, many of the most successful chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells integrate a constitutively active 4-1BB stimulatory domain [49, 50]. Most monoclonal antibodies directed against 4-1BB are hypothesized to act on CD8 T cells to maximize their activation and anti-tumor immune response [9, 51]. Others have also demonstrated the importance of 4-1BB expression on other immune cells including dendritic cells [52, 53] and B cells [54, 55]. Besides their role in producing antibodies, B cells are important for priming CD8 [56] and CD4 T cell [37] responses, and playing a critical role in organization of tertiary lymphoid structures, which have been associated with improved outcomes [57, 58].

In this study, we report that combining anti-4-1BB immunotherapy with ablative RT allows for vigorous immune activation with recruitment of B cells and CD4 T cells for improved local and distant tumor control. Further we demonstrate the impact of RT on changes in CD4 T cells and 4-1BB expression in human extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC).

Materials and methods

Mice

Age-matched C57BL/6 J (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000,664) mice were procured from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained by the Moffitt Cancer Center animal facility according to the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and National Institute of Health (NIH) standards. All experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of South Florida.

Cell culture and in vivo tumor experiments

B16-F10 melanoma cells (NCI-DTP Cat# B16F10, RRID: CVCL_0159) were transduced to express the ovalbumin (OVA) antigen with the pAc-neo-OVA (RRID:Addgene 22533) as described previously. B16-OVAcells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 0.8 mg/mL G418 and 1% L-glutamine at 37 °C and 5% CO2. One million B16-OVA were then implanted subcutaneously in the bilateral flanks of C57BL/6 J mice 10–15 days prior to treatment intervention. For experiments focused on tumor harvest for flow cytometric analyses, initiation of treatment was delayed until tumors were closer to approximately 500mm3 to ensure adequate residual tumor tissue for evaluation of immune cell infiltrates up to 10 days following commencement of treatment interventions with radiotherapy and/or anti-4-1BB antibody therapy. LLC murine cells (CLS Cat# 400,263/p546_Lewis-Lung, RRID:CVCL_4358) were maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% L-glutamine at 37 °C and 5% CO2. One million LLC cells were implanted subcutaneously in the right flank of C57BL/6 J mice and allowed to grow approximately 12 days until the tumor was palpable (local tumor). For those receiving a contralateral tumor, 5 × 105 LLC cells were injected into the left flank (distant tumor) following the 12-day growth of the right flank tumor. Flank tumors were measured with calipers and tumor volumes calculated as (length x width2)/2.

Antibodies

Antibodies targeting 4-1BB were obtained from Compass Therapeutics (CTX 471-AF) and BioXCell (3H3, Cat. # BE0239). Anti-mouse 4-1BB (CTX-471-AF or 3H3) therapy was administered intraperitoneally on consecutive days, with 3 total doses of 100 µg delivered concurrently with RT. For immune cell depletion, anti-CD4 (GK1.5) (Bio X Cell Cat# BE0003-3, RRID: AB_1107642, 200 µg), anti-CD8 (Lyt 3.2) (Bio X Cell Cat# BE0223, RRID: AB_2687706, 200 µg), or anti-B220 (RA3.3A1/6.1) (Bio X Cell Cat# BE0067, RRID:AB_1107651, 300 µg) were administered intraperitoneally on day 2 after initiation of RT and anti-4-1BB.

Tumor irradiation

Mice that received RT were anesthetized and treated with a small cabinet irradiator (XRAD 320, Precision Xray, North Branford, CT). Three uniform daily fractions of 8 Gy were delivered to the right flank on consecutive days beginning when the tumors reached an average size of 20mm3, while the remainder of the body was shielded. The dose and fractionation of radiation treatment schedule were selected based on multiple previously published studies which indicate need for fractionated ablative (5–10 Gy) but not supra-ablative (> 10–12 Gy) doses of radiation to enhance responses to immunotherapy [19, 62].

Human specimens

Human peripheral blood from patients with ES-SCLC receiving thoracic RT was collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center (NCT03043599) within 72 h prior to RT and within 72 h after the final RT fraction63. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Flow cytometry

Tumor, spleen, and draining bilateral lymph nodes were harvested from mice either 5 or 10 days after initiation of tumor irradiation and treatment with agonist 4-1BB antibody. Samples were mechanically dissociated, followed by red blood cell lysis prior to staining. Mouse staining was done using antibodies against the following markers: CD45 (BioLegend Cat# 103,113, RRID:AB_312978), CD3 (BD Biosciences Cat# 563,565, RRID:AB_2738278), CD4 (BD Biosciences Cat# 612,900, RRID:AB_2827960), CD8 (BioLegend, 612,759), CD44 (BioLegend Cat# 103,026, RRID:AB_493713), B220 (BD Biosciences Cat# 612,839, RRID:AB_2870161), CD80 (BioLegend Cat# 104,711, RRID:AB_313132), CD86 (BioLegend Cat# 105,035, RRID:AB_11126147), CD11c (BioLegend Cat# 117,320, RRID:AB_528736), CD40L (BD Biosciences Cat# 561,719, RRID:AB_10897018), CD103 (BioLegend Cat# 121,429, RRID:AB_2566492), 4-1BB (BioLegend Cat# 106,110, RRID:AB_2564297), CD69 (BD Biosciences Cat# 562,920, RRID:AB_2737893). Data were collected using a BD LSRII flow cytometer and gated by lymphocytes, single cells, CD45 + cells, with concomitant B220 + cells, CD3 + cells (either CD4 or CD8) or CD11c + cells. Human peripheral blood immune cell staining was performed using antibodies against CD3 (BD Biosciences Cat# 564,809, RRID: AB_2744388), CD4 (BD Biosciences Cat# 564,305, RRID: AB_2713927), CD25 (BD Biosciences Cat# 560,503, RRID: AB_1727453), 41BB (BD Biosciences Cat# 564,091, RRID: AB_2722503), CD69 (BD Biosciences Cat# 557,745, RRID: AB_396851), and CD45RA (BD Biosciences Cat# 555,488, RRID: AB_395879). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software v10.8.

Statistical analyses

A Kaplan–Meier estimate was performed to measure delay of unirradiated tumor growth by measuring the time from inoculation until the tumor reached a volume of 150mm3. Tumor growth was censored on the last observation day for mice not reaching volumes of 150 mm3. A log-rank test was conducted to test the difference between treatment groups. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. All statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Prism, RRID: SCR_002798). Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction were used for calculating differences between means using multiple comparisons between groups. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was used.

Results

B cells and CD4+T cells accumulate in the tumor microenvironment after radiotherapy

To understand changes in the immune-environment of established tumors in response to RT, we first treated C57BL/6 J mice with established bilateral B16-OVA flank tumors (Fig. 1A). At 5 days after initiation of radiotherapy, we observed an early influx of CD4+ T cells without a significant change in Treg (CD4+CD25+CD127−) cells (Fig. 1B), followed by late accumulation of CD8+ T cells at ~ day 10 (Fig. 1C). Coinciding with CD4+ T cell accumulation, we observed an increase in the number of B cells. These B cells were activated, as indicated by increased CD86+ expression from day 5 to day 10 after RT (Fig. 1D). Although we detected no change in the ratio of DCs as a percent of CD45+ on day 5 and a decrease in proportion of DCs on day 10 (likely due to significant influx of CD8+ cells), we observed an increase in activation of DCs, as evidenced by increased CD86+ surface expression at both temporal points (Fig. 1E). At early temporal points, we also found a sharp increase in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio in the bilateral draining lymph nodes (Fig. 1F), concomitant to an increase in CD40L expression on CD4+ T cells in the unirradiated draining lymph node (Fig. 1G), in tumor-bearing mice receiving RT, compared to no treatment controls. Though we did not find significant changes in the proportion of DCs in bilateral draining lymph nodes (Fig. 1H), we identified CD103+ dendritic cells (Fig. 1I), which are increased with radiation treatment in the draining lymph node on the irradiated side, as has been previously reported 64.

Fig. 1.

B cells and CD4+ T cells migrate to the tumor microenvironment after radiotherapy. (A) Experimental design. 10^6 B16-F10 melanoma cells transduced with the OVA-antigen were injected subcutaneously in bilateral flanks of C57/BL6 mice. Upon tumor growth around 10–12 days, treatment to the right flank was initiated with a total dose of 8 Gy × 3 daily. Tumor microenvironment was studied by flow cytometry at days 5 and 10, following radiotherapy. (B-left) CD4/CD8 ratio increases after RT on day 5, with a subsequent decrease on day 10. (B-center) The percentage of CD4+ of CD45+ viable cells increased in response to RT on day 5 with no significant changes on day 10. (B-right) T regulatory cell (CD4+CD25+CD127−) population shows no significant change as a percentage of CD4+ T cells on day 5 or day 10 (C) The percentage of CD8+ of CD45+ viable cells demonstrated no significant change on day 5 with significantly increased %CD8+ T cells 10 days after RT. (D-Left) The percentage of B cells (CD45+B220+) is significantly increased on day 5 with no significant change on day 10. (D-Right) The percentage of activated (CD86+) B cells are significantly increased on days 5 and 10 after radiation. (E-Left) The percentage of dendritic cells (CD11c+) in the CD45+ compartment have no significant change on day 5 or day 10 after RT. (E-Right) The percentage of activated (CD86+) dendritic cells are significantly increased on days 5 and 10 after radiation. (F) The ratio of CD4/CD8 T cells is significantly increased in bilateral draining lymph nodes on day 10 after RT. (G) The percentage of CD40L + CD4 cells in bilateral draining lymph nodes was increased in the RT group compared to control. (H) The percentage of DCs in the CD45 compartment in bilateral draining lymph nodes was unchanged with RT. (I) The percentage of DCs in the CD103 compartment in irradiated inguinal lymph nodes was significantly increased with RT without changes in the unirradiated lymph node. RT, radiotherapy. CTRL, control ns, not significant. DC, dendritic cell. Data show mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)

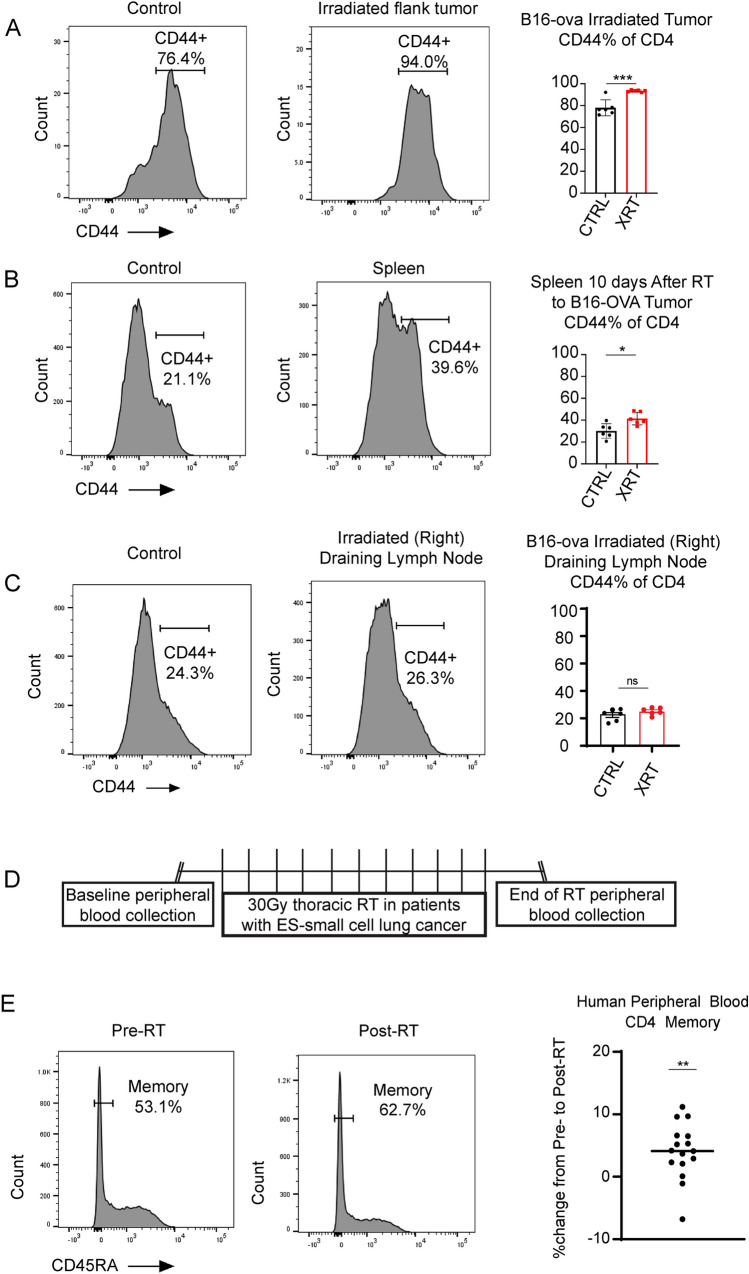

Radiotherapy increases hallmarks of antigen exposure and 4-1BB expression in T and B cells in mice and humans

To further support the role of CD4+ T cells, we found that after RT, CD4 T cells demonstrate significantly increased evidence antigen exposure, with increased %CD44+ at both the irradiated tumor site (Fig. 2A), and in the spleen (Fig. 2B) although no differences were detected at the irradiated lymph node sites (Fig. 2C). There was an increase in antigen exposed CD8+CD44+ T cells 10 days following radiotherapy in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 1B), but we did not see any significant change in CD8+CD44+ T cells in the irradiated tumors (Supplementary Fig. 1A) or irradiated draining lymph nodes (Supplementary Fig. 1C). CD44 is a well-established murine marker which characterizes antigen exposed T cell memory population. In humans, we utilize loss of CD45RA expression and/or increased expression of CD45RO to characterize a similar antigen exposed memory phenotype65. The relevance of concurrent CD4+ T cell activation was further supported by the results from a clinical trial of patients with ES-SCLC receiving 30 Gy in 10 fractions of thoracic radiation (Fig. 2D). Treatment with RT increased antigen exposure evidenced by significantly decreased CD45RA expression on CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2E), while the exhaustion/activation marker PD-1 did not show significant change with RT at our experimental time points (data not shown). We also evaluated changes in CD8+CD45RA− in the peripheral blood of these treated patients but did not see any significant changes following thoracic radiotherapy. (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

Fig. 2.

CD4+ T cells demonstrate increased evidence of antigen exposure at the tumor site and spleen in mice and in human peripheral blood with RT. Representative examples and flow cytometry analysis demonstrating increased antigen exposed CD4+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD4+ T cells at the tumor site (A) and in the peripheral spleen (B) while no change is observed in the irradiated draining lymph nodes (C) in B16-OVA mouse model described in Fig. 1A. (D) Schematic of experimental design of human small cell lung cancer clinical trial demonstrating peripheral blood collection at baseline and within 72 h after receipt of 30 Gy thoracic RT in 10 fractions. (E) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrating significantly increased antigen-exposed CD4+CD45RA− memory T cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer trial receiving thoracic RT. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare pre-RT and post-RT time points

Analysis of additional activation markers in T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells at irradiated tumor sites in tumor-bearing mice showed that a significant percentage of both CD4 T cells (Fig. 3A) and B cells (Fig. 3B) turn on 4-1BB after RT at early time points. Further supporting that CD4 T cell activation precedes the immunostimulatory effects of RT on CD8 T cells, the percentage of 4-1BB positive CD8 lymphocytes only increased after 10 days (Fig. 3C), coinciding with the accumulation of this population at tumor beds (Fig. 1C). We also found a trend toward increase in 4-1BB positive DCs (Fig. 3D), given the scarcity of this population. Further supporting the clinical relevance of these findings, 4-1BB expression following RT was also significantly increased on peripheral CD4+ T cells following thoracic RT in humans with ES-SCLC (Fig. 3E and 3F), with significant increases in the mobilization of activated 4-1BB+ CD69+CD4+ T cells post-RT (Fig. 3G and 3H). Careful analyses of CD4 T cell populations excluding (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and specifically evaluating (Supplementary Fig. 2B) Treg cells (CD4+CD25+CD127−) confirms that changes in CD4 T 4-1BB surface expression are not due to changes in this population. Peripheral blood analyses revealed possible trend toward increased 4-1BB on B cells (Supplementary Fig. 2C) but no consistent changes in peripheral CD8 T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2D) were seen after thoracic RT. These data suggest that the immunostimulatory effects of RT in fact depend on early activation of CD4+ T cells and B cells, with subsequent activation of CD8+ T cells at later temporal points. Moreover, upregulation of 4-1BB on these populations provides a rationale for combined 4-1BB agonists.

Fig. 3.

Radiation activates both T and B cells, increasing expression of 4-1BB in the B16-OVA murine model and in patients with ES-SCLC (A) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating a statistically significant increase in percentage of 41BB+ CD4+ T cells among irradiated tumors at both 5- and 10-days following RT. (B) Significant increase in % of 4-1BB+ B cells among irradiated tumors at 5 days but not 10 days following RT. (C) No difference in % of 4-1BB+ CD8+ T cells at 5 days after RT but significantly increased % of 4-1BB+ CD8+ cells among irradiated tumors 10 days following RT. (D) Quantification by flow cytometry demonstrating low expression with no significant change in 4-1BB-expressing dendritic cells among irradiated tumors at either temporal point. (E) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating increased % of 4-1BB+ peripheral CD4+ T cells in a patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Fig. 2D. (F) Composite analysis demonstrating fold change increase in CD4+4-1BB+ above baseline after RT for almost all patients (left) and absolute change from baseline (right) of 4-1BB+ CD4+ T cells following RT. (G) Flow cytometry analyses showing increased 4-1BB+, CD69+ CD4+ T cells following RT in a representative patient with ES-SCLC. (H) Flow cytometry composite analyses of all patients on SCLC trial with available data before and after RT demonstrating statistically significant increased fold change above baseline (left) and absolute change from baseline (right) of 4-1BB+, CD69+ CD4+ T cells. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare pre-RT and post-RT time points across the study cohort

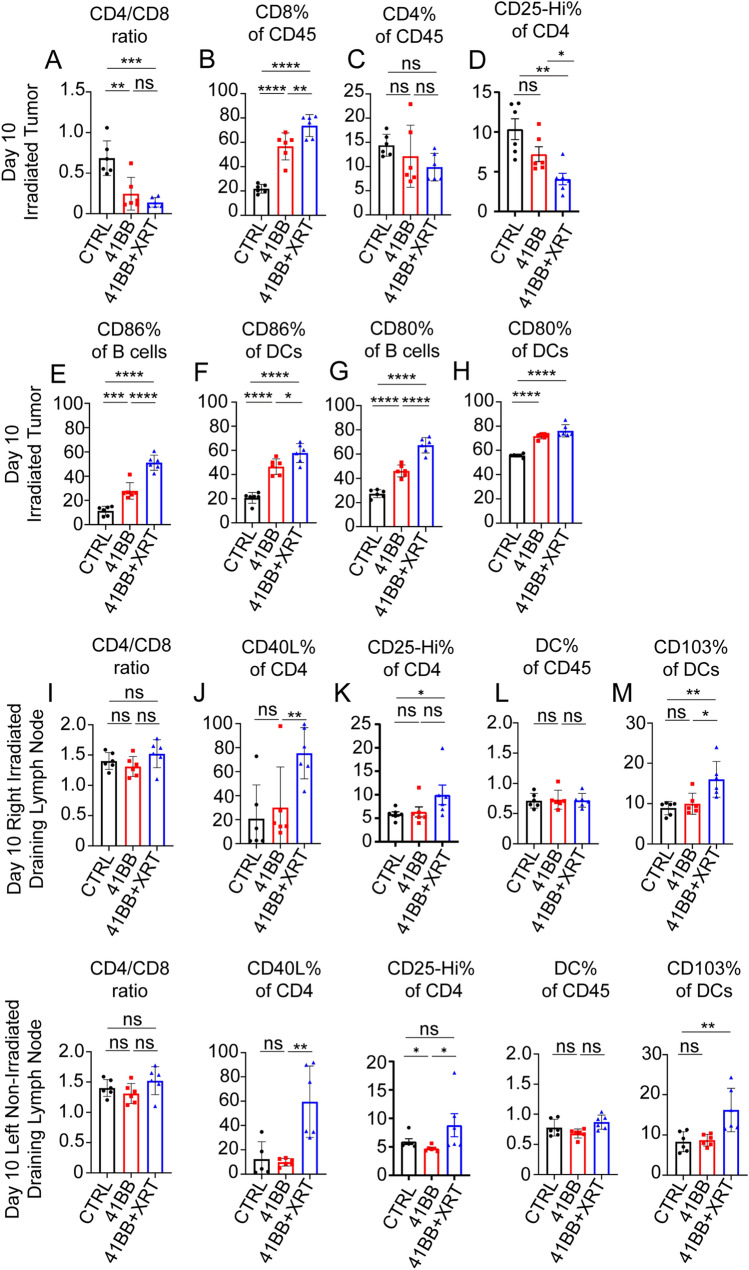

Anti-4-1BB agonists enhance CD8 T cell infiltration and abscopal effects of radiotherapy at non-irradiated tumor sites

Based on our results that showed increased 4-1BB expression with RT, we sought to combine ablative radiation therapy with an anti-mouse 4-1BB antibody (CTX-471-AF) that binds 4-1BB at a non-ligand Blocking epitope, thereby allowing for natural 4-1BB-L/4-1BB interactions to drive T cell activation 9. Combining RT and CTX-471-AF resulted in significant increases in the influx of CD8 T cells (Fig. 4A and 4B), compared to no treatment or CTX-471-AF alone, without significant changes in the CD4+ T cell compartment at later temporal points (Fig. 4C). A reduction in CD4+CD25+ T cells as a percent of CD4+ T cells was seen at the irradiated tumor site with combination treatment (Fig. 4D). Combination of 4-1BB agonism and RT also induced increased proportions of CD80+ and CD86+ B cells (Fig. 4E and 4G) as well as CD80+ and CD86+ DCs (Fig. 4F and 4H). Furthermore, upon evaluation of the draining lymph nodes of both tumor beds while no differences in the proportion of CD4/CD8 T cells were observed (Fig. 4I), we found that combining RT plus 4-1BB agonism resulted in increased surface expression of CD40L among CD4+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (Fig. 4J). There was a slight increase in CD4+CD25+ T cells as a percent of CD4+ T cells with combination therapy in draining lymph nodes (Fig. 4K). Though there were no differences in the proportion of dendritic cells in the bilateral draining lymph nodes with the combination therapy (Fig. 4L), we found increased accumulation of CD103+ dendritic cells (Fig. 4M). Most importantly, utilizing the B16-OVA model demonstrated that the growth of unirradiated tumors was delayed but could not be routinely controlled using RT alone (Fig. 5A and 5B) and complete tumor control of unirradiated tumor sites could be only achieved using combination therapy (Fig. 5C). Tumor control at irradiated tumor sites was excellent with RT alone and combination treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3A-C). To demonstrate the general applicability of these results in a less immunogenic tumor model, we evaluated the impact of another 4-1BB agonist (clone 3H3) and RT in a separate Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) model. Utilizing a similar dual flank approach with RT to the right flank only, we show that RT with anti-4-1BB agonist significantly improved tumor control at the unirradiated flank compared to RT alone or anti-4-1BB monotherapy (Fig. 5E–H). Tumor control at irradiated tumor sites was delayed but not completely controlled with RT alone (Supplementary Fig. 3D-E) with further improved tumor control utilizing combined RT and 4-1BB agonist antibody treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3F). Therefore, in two model systems, RT and 4-1BB agonists elicit abscopal effects that abrogate the growth of tumor lesions distal to irradiated sites, which is associated with distinct changes in the tumor immuno-environment.

Fig. 4.

The addition of anti-4-1BB agonist antibody to RT enhances immune cell activation and migration to the tumor microenvironment in B16-OVA tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice. 10^6 B16-F10 melanoma cells transduced with OVA-antigen were injected subcutaneously in bilateral flanks of C57/BL6 mice. Upon tumor growth between 10 and 12 days, treatment to the right flank was initiated with total dose of 8 Gy × 3 daily with or without concurrent 100 µg 4-1BB antibody (CTX-471-AF). Mice were euthanized and tumors were evaluated 10 days following treatment. (A) CD4/CD8 ratio after RT decreases significantly with CTX-471-AF (4-1BB agonist) in combination with RT. (B) Percentage of CD8+ T cells in the CD45 compartment increases significantly with CTX-471-AF therapy, and even more so with the combination therapy, without significant change in the proportion of CD4+ T cells (C). Significant decrease in CD4+CD25+ T cell population is observed when administering CTX-471-AF or combination treatment (D) B cells (B220+) show increased CD86% + (E) and CD80% + (G) with anti-4-1BB therapy and are increased even further with combination of 4-1BB agonism and RT. Similar increases in CD86% + (F) and CD80% + (H) populations are seen among dendritic cells treated with anti-4-1BB and anti-4-1BB concurrent with RT treatments. (I) There were no significant changes in the CD4/CD8 ratio in either of the bilateral draining lymph nodes 10 days after RT. (J) Increased expression of CD40L on CD4+ T cells in bilateral draining lymph nodes in response to combination 4-1BB agonism and RT, without significant changes with anti-4-1BB alone compared to no treatment control. (K) Changes in CD4+CD25+ T cell population in irradiated and non-irradiated draining lymph nodes 10 days after RT. (L) No significant changes in proportion of dendritic cells in the CD45 compartment in bilateral draining lymph nodes in response to either 4-1BB agonism alone or the combination of 4-1BB agonism and RT. (M) The proportion of dendritic cells (CD11c+) expressing CD103 in bilateral draining lymph nodes is significantly increased with combination 4-1BB agonism and RT without significant changes with anti-4-1BB alone, compared to no treatment controls. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons

Fig. 5.

The 4-1BB and RT-induced anti-tumor immune activation improves tumor control at unirradiated tumor sites in two unique tumor models 10^6 B16-F10 melanoma cells transduced with OVA-antigen were injected subcutaneous bilateral flanks of C57BL/6 mice. Upon tumor growth around 10–12 days, treatment to the right flank was initiated with total dose of 8 Gy × 3 daily with or without concurrent 100ug 4-1BB antibody (CTX-471). Mice were followed until euthanasia criteria were met. Tumor growth curves (left) and Kaplan–Meier time to contralateral flank growth of 150mm3 (right) (A) Tumor growth in left flank of untreated mice inoculated with 10^6 B16-OVA (B) Tumor growth of unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT alone to the right flank compared to no treatment. (C) Tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX471 compared to no treatment. (D) Tumor growth curve in unirradiated left flanks of mice receiving CTX471 treatment without radiation to the right flank compared to no treatment. 10^6 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were injected into subcutaneous bilateral flanks of C57BL/6 mice and mice were similarly treated with radiation to the right flank to a total dose of 8 Gy × 3 daily with or without concurrent 100 µg 4-1BB antibody (3H3). Inoculation of the left flank was delayed by 12 days. Tumor growth curves (left) and Kaplan–Meier time to unirradiated flank growth of 150 mm3 (right) (E) Tumor growth in left flank of untreated mice inoculated with 10^6 LLC (F) Tumor growth of unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT alone to the right flank compared to no treatment. (G) Tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent 3H3 compared to no treatment. (H) Tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks receiving 3H3 treatment without radiation to the right flank compared to no treatment

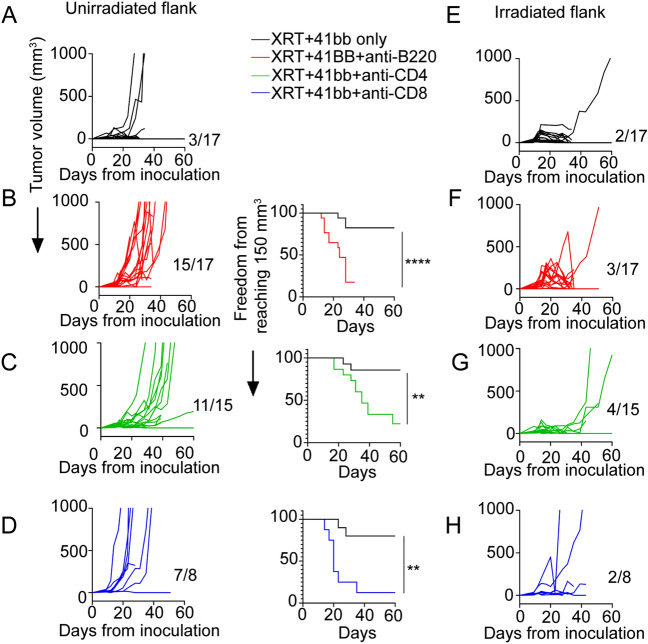

B cells and CD4+ T cells are required for the distinct therapeutic benefits of combined RT and 4-1BB agonist therapy

Early accumulation and activation of B cells and CD4 T cells suggest that their crosstalk could be required for CD8 T cell-dependent protective effects elicited by RT Plus 4-1BB agonists. Accordingly, we found that early B cell depletion prevents the control of tumor growth at the unirradiated flank tumor elicited by combined RT and CTX-471-AF, with ~ 90% of tumors demonstrating accelerated malignant progression and reaching endpoint significantly sooner than the control cohort (Fig. 6A-B). Similarly, early depletion of CD4 T cells after combined therapy also allowed the growth of unirradiated tumor sites, with over 70% of tumors demonstrating accelerated growth and reaching endpoint sooner than the control group (Fig. 6C). As expected, depletion of CD8 T cells also resulted in accelerated growth in nearly all tumors, and those mice with CD8 depletion were significantly more likely to reach endpoint sooner than the control group (Fig. 6D). Depletion of B cell as well as CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes led to initial early tumor regrowth at some irradiated tumor sites but ultimately tumor control was achieved in most cases similar to treatment without lymphocyte depletion (Fig. 6E–H). Therefore, the combined effects of RT and 4-1BB agonism in anti-tumor immunity depend on the crosstalk between multiple immune cell populations, whereby the early activation of CD4 T cells and B cells precedes the activation and accumulation of CD8 T cells, which elicit systemic protective anti-tumor immunity beyond irradiated tumor sites.

Fig. 6.

4-1BB Agonism and RT-induced tumor control at unirradiated tumor sites is dependent on infiltration of B cells, as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (A) B16-OVA tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX-471-AF. (B) Addition of B cell depleting antibody (anti-B220, 300 µg) two days following initiation of RT compared to a similarly treated cohort without B cell depletion. (C) Tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX-471-AF and CD4 depleting antibody (anti-CD4, 200 µg) two days following initiation of RT compared to a similarly treated cohort without CD4+ T cell depletion. (D) Tumor growth in unirradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX-471-AF and CD8 depleting antibody (anti-CD8, 200 µg) two days following initiation of RT compared to a similarly treated cohort without CD8+ T cell depletion. (E) B16-OVA tumor growth in irradiated right flank among mice receiving RT with concurrent CTX-471-AF. (F) B16-OVA tumor growth in irradiated right flank of mice that received additional B cell depleting antibody (anti-B220, 300 µg) two days following initiation of RT. (G) Tumor growth in irradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX-471-AF and CD4 depleting antibody (anti-CD4, 200 µg) two days following initiation of RT. (H) Tumor growth in irradiated left flanks among mice receiving RT to right flank with concurrent CTX-471-AF and CD8 depleting antibody (anti-CD8, 200 µg) two days following initiation of RT

Discussion

We showed that radiotherapy and 4-1BB agonist therapy work synergistically to induce B cell-dependent anti-tumor immune activation and improve tumor control in advanced metastatic melanoma and lung cancer. We demonstrated increased B cell activation and migration to the tumor microenvironment in response to RT. In the immunogenic B16-OVA melanoma model, we see a moderate abscopal effect even with RT alone which is amplified in combination with 4-1BB agonist therapy. Given the critical role of B cells which we have demonstrated in our depletion studies and the previously reported role of humoral immune response to B16-OVA we anticipate that this abscopal effect with RT alone may be driven by anti-tumor antibody response59. In contrast, utilizing the non-immunogenic LLC model, the abscopal effect requires addition of 4-1BB agonist therapy to demonstrate enhanced abscopal effects. The activation and migration of CD8 T cells is even more pronounced with the combination of RT and CTX-471-AF anti-4-1BB therapy. In our murine model, we demonstrate improved delayed malignant progression with the combination therapy, which is eliminated when B cells are depleted. These data strongly suggest that B cells play an important role in response to therapy with CTX-471-RF and RT. We intend to further study the important role of B cells in radiotherapy including thoroughly evaluating the function of these B cells which are migrating to the tumor microenvironment.

We additionally demonstrate early (day 5) influx of CD4+ T cells in response to RT, with even further increase with the addition of anti-41BB to the RT. There is also a massive influx of CD8 T cells to the tumor microenvironment at the later temporal point (day 10), both of which are crucial to the control of malignant progression with combination therapy, as demonstrated by CD4 and CD8 T cell depletions. The critical role of CD8+ T cells demonstrated in this work has also been shown by others [66–68]. However, unlike previous reports, we are highlighting the importance of the early influx of CD4+ T cells and their role in the anti-tumor response. Herrera et al. have also recently demonstrated the important role of CD4+ T cells even after lower doses of radiation therapy [39]. We anticipate that likely the activation and upregulation of 4-1BB, CD40L and interactions with B cells drive robust immune activation to ultimately stimulate proliferation and activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cell killing.

CD4+ T and B cells migrate to the tumor and draining lymph nodes and demonstrate features of activation and proliferation. These effects are increased by the addition of anti-4-1BB therapy, utilizing CTX-471-RF, a murine surrogate for a novel anti-4-1BB agonist being utilized in human trials from Compass Therapeutics (NCT03881488). Unfortunately, the role of CD4+ T cells have long been minimized because they are not typically involved in direct cytotoxic tumor cell killing. Likewise, B cells have been largely ignored with more preference on maximizing CD8+ T cell function. The results from our study highlight new opportunities for synergy between 4-1BB agonism and RT to act as an in situ vaccine. With an improved understanding of the immune activation after RT, we can design rational clinical trials aimed to maximize synergy with RT, novel anti-4-1BB agonists and other APC/B cells stimulating treatments to foster a more robust anti-tumor immune response in the tumor microenvironment.

In our human samples, we also see evidence of increased 4-1BB expression, with increased CD69+ on CD4+ T cells, which is significantly associated with radiation therapy. These cells may be coordinating combined humoral and cell mediated immune responses in conjunction with B cells and other important immune contributors. Peripherally, we did not detect changes in expression of 4-1BB in B cells or CD8+ T cells at the evaluated time points, although we anticipate these changes are more likely to be present at the site of radiation therapy similar to what we have seen in our in vivo models. Our data evaluating the draining lymph nodes of irradiated tumors also indicates changes in CD4+ T cells, but not B cells or CD8+ T cells at regional (draining lymph nodes) and peripheral sites (spleen). This suggests that following RT, CD4+ T cells are activated and spreading anti-tumor response. One reason the CD4 depletion cohort has intermediate/less obvious phenotype compared to B cells and CD8+ T cells may be explained by concurrent Treg depletion.

Our study is not without limitations including most importantly that changes seen murine tumor models may not recapitulate human tumor microenvironment. Although our findings highlight early B and CD4 T cell migration to tumor and lymph nodes in mice, we are unable to include details about intratumoral lymphocyte 4-1BB activation or confirm the critical anti-tumor immune response of CD4 T or B cells in irradiated human tumors after radiotherapy. Furthermore, although our work suggests combination treatment with radiation and anti-4-1BB therapy as a novel way to harness diverse lymphocyte subsets to drive anti-tumor immune responses, further investigation to understand the role of B cells and CD4 T cell contributions to abscopal radiation effects must be explored. This includes careful evaluation of CD40/CD40L interactions and downstream TRAF signaling which may be critical for development of radiation-induced anti-tumor humoral and cell mediated immune responses. Improved understanding of how to maximize tumor antigen specific immune cell proliferation beyond irradiated tumors may provide additional insights to maximize synergy of radiation with immunotherapy in future studies.

Distant tumor control with RT and CTX-471-RF depends on B cells and CD4+ T cells which play important early roles in RT response. These relevant and activated lymphocytes demonstrate increased surface expression of 4-1BB after RT. Combined treatment with CTX-471-RF and RT improves radiation response and systemic anti-tumor response. Our results demonstrate that radiation therapy can be successfully combined with systemic immunotherapy, including novel anti-4-1BB agonist antibodies and future clinical trials to combine these therapies may improve outcomes for patients with melanoma and lung cancer.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1(Supplementary Figure 1 Radiation-induced changes in CD8+ T cells at irradiated tumor sites, spleen, and irradiated draining lymph nodes of mice. (A) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrating no change in antigen exposed CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells at the irradiated tumor site compared to unirradiated control cohort. (B) slight increase in CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells in the peripheral spleen (C) no change in CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells is observed in the irradiated draining lymph nodes in B16-OVA mouse model described in Figure 1A. (D) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrating no significant increase in peripheral blood antigen-exposed CD8+CD45RA- memory T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare Pre-RT and Post-RT time points across the study cohort) (TIF 24441 KB)

Supplementary file2 (Supplementary Figure 2 4-1BB upregulation in peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets following thoracic RT (A-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating increased % of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg (Treg=CD4+CD25+CD127-) CD4+ T cells as a percent of non-Treg CD4+ T cells after RT in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (A-right) Composite flow cytometry analysis demonstrating significant absolute changes from baseline of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg CD4+ T cells following RT following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. (B-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ peripheral Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127-) in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (B-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change from baseline of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg CD4+ T cells following RT. (C-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ B cells in a patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (C-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change of 4-1BB+ peripheral B cells as a percent of total B cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. (D-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ CD8+ T cells as a percent of total CD8+ T cells in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (D-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change of 4-1BB+ peripheral 4-1BB+ CD8+ T cells as a percent of total CD8+ T cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare Pre-RT and Post-RT time points across the study cohort) (TIF 22774 KB)

Supplementary file3 (Supplementary Figure 3 RT alone and RT with 4-1BB agonism control tumor growth at irradiated tumor sites. (A)B16-OVA tumor growth in right flank of untreated mice. (B) Tumor growth curve of irradiated flank tumors in mice receiving ablative RT as outlined in Figure 1A. (C) Tumor growth of irradiated flank tumors in mice receiving ablative RT with combination of CTX-471-AF. (D) Right flank tumor growth curves of untreated mice inoculated with 10^6 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells. (E) Tumor growth curve of irradiated tumor flanks of mice that received ablative (8Gy x 3) RT treatment directed at the right tumor flank. (F) Tumor growth curve of irradiated tumors of mice that received a combination of RT with CTX-471-AF) (TIF 10012 KB)

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Alexandra Martin, Chase Powell, Derek Nichols, Pasquale Innamarato, Mate Nagy, Min-hsuan Wang, Bing Gong, Xianzhe Wang, Thomas Scheutz. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alexandra Martin, Chase Powell, Sungjune Kim, Jose Conejo-Garcia and Bradford Perez. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by K08 (5K08CA231454) Career Development Award supporting B.A.P.; and by R01CA124515 and R01CA240434 to JRCG. Support for Shared Resources was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA076292 to H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing Interests

B.A.P has research funding (Bristol Myers Squibb) and has served on advisory board (AstraZeneca, G1 Therapeutics); all outside the submitted work. S. J. A. has served on advisory boards for Bristol Myers Squibb, Celsius, Merck, Samyang Biopharma, AstraZeneca/Medimmune; Consultant: Bristol Myers Squibb, Celsius, Merck, Samyang Biopharma, AstraZeneca/Medimmune, CBMG, Memgen, RAPT, Venn, Achilles Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen; Scientific advisory board: CBMG, Memgen, RAPT, Venn, Achilles Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen. J.R.C.G. has stock options in Compass Therapeutics, Anixa Biosciences and Alloy Therapeutics. He also receives consulting fees from Leidos, Alloy Therapeutics and Radyus Research; has sponsored research with Anixa Biosciences; and patent applications with Compass Therapeutics and Anixa Biosciences; all outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval

Animals for this study were maintained by the Moffitt Cancer Center animal facility according to the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and National Institute of Health (NIH) standards. All experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of South Florida.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Alexandra L. Martin and Chase Powell contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Munhoz RR, Postow MA. Clinical development of PD-1 in advanced melanoma. Cancer J. 2018;24(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin J, Lao CD, Urba WJ, McDermott DF, Horak C, Jiang J, Wolchok JD. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in patients with BRAF V600 mutant and BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):433–440. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbe C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Waterhouse D, Ready N, Gainor J, Aren Frontera O, Havel L, Steins M, Garassino MC, Aerts JG, Domine M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Baudelet C, Harbison CT, Lestini B, Spigel DR. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizvi NA, Mazieres J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B, Otterson GA, Campos LT, Gandara DR, Levy BP, Nair SG, Zalcman G, Wolf J, Souquet PJ, Baldini E, Cappuzzo F, Chouaid C, Dowlati A, Sanborn R, Lopez-Chavez A, Grohe C, Huber RM, Harbison CT, Baudelet C, Lestini BJ, Ramalingam SS. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, Barlesi F, Kohlhaufl M, Arrieta O, Burgio MA, Fayette J, Lena H, Poddubskaya E, Gerber DE, Gettinger SN, Rudin CM, Rizvi N, Crino L, Blumenschein GR, Jr, Antonia SJ, Dorange C, Harbison CT, Graf Finckenstein F, Brahmer JR. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiragolumab Impresses in Multiple Trials (2020) Cancer Discov 10(8):1086–1097. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2020-063 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, Castillo Gutierrez E, Rutkowski P, Gogas HJ, Lao CD, De Menezes JJ, Dalle S, Arance A, Grob JJ, Srivastava S, Abaskharoun M, Hamilton M, Keidel S, Simonsen KL, Sobiesk AM, Li B, Hodi FS, Long GV, Investigators R. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(1):24–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskiocak U, Guzman W, Wolf B, Cummings C, Milling L, Wu HJ, Ophir M, Lambden C, Bakhru P, Gilmore DC, Ottinger S, Liu L, McConaughy WK, He SQ, Wang C, Leung CL, Lajoie J, Carson WFt, Zizlsperger N, Schmidt MM, Anderson AC, Bobrowicz P, Schuetz TJ, Tighe R, Differentiated agonistic antibody targeting CD137 eradicates large tumors without hepatotoxicity. JCI Insight. 2020 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amatore F, Gorvel L, Olive D. Role of Inducible Co-Stimulator (ICOS) in cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020;20(2):141–150. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1693540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aspeslagh S, Postel-Vinay S, Rusakiewicz S, Soria JC, Zitvogel L, Marabelle A. Rationale for anti-OX40 cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen EEW, Pishvaian MJ, Shepard DR, Wang D, Weiss J, Johnson ML, Chung CH, Chen Y, Huang B, Davis CB, Toffalorio F, Thall A, Powell SF. A phase Ib study of utomilumab (PF-05082566) in combination with mogamulizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0815-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segal NH, Logan TF, Hodi FS, McDermott D, Melero I, Hamid O, Schmidt H, Robert C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Ascierto PA, Maio M, Urba WJ, Gangadhar TC, Suryawanshi S, Neely J, Jure-Kunkel M, Krishnan S, Kohrt H, Sznol M, Levy R. Results from an integrated safety analysis of urelumab, an agonist anti-CD137 monoclonal antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(8):1929–1936. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi X, Li F, Wu Y, Cheng C, Han P, Wang J, Yang X. Optimization of 4–1BB antibody for cancer immunotherapy by balancing agonistic strength with FcgammaR affinity. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2141. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abuodeh Y, Venkat P, Kim S. Systematic review of case reports on the abscopal effect. Curr Probl Cancer. 2016;40(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone HB, Peters LJ, Milas L. Effect of host immune capability on radiocurability and subsequent transplantability of a murine fibrosarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979;63(5):1229–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarty PK, Alfieri A, Thomas EK, Beri V, Tanaka KE, Vikram B, Guha C. Flt3-ligand administration after radiation therapy prolongs survival in a murine model of metastatic lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59(24):6028–6032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, Hesser J, Demaria S, Formenti SC. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(5):313–322. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2018.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5379–5388. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBride S, Sherman E, Tsai CJ, Baxi S, Aghalar J, Eng J, Zhi WI, McFarland D, Michel LS, Young R, Lefkowitz R, Spielsinger D, Zhang Z, Flynn J, Dunn L, Ho A, Riaz N, Pfister D, Lee N. Randomized phase II trial of nivolumab with stereotactic body radiotherapy versus nivolumab alone in metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(1):30–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theelen W, Peulen HMU, Lalezari F, van der Noort V, de Vries JF, Aerts J, Dumoulin DW, Bahce I, Niemeijer AN, de Langen AJ, Monkhorst K, Baas P. Effect of pembrolizumab after stereotactic body radiotherapy vs pembrolizumab alone on tumor response in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results of the PEMBRO-RT phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee NY, Ferris RL, Psyrri A, Haddad RI, Tahara M, Bourhis J, Harrington K, Chang PM, Lin JC, Razaq MA, Teixeira MM, Lovey J, Chamois J, Rueda A, Hu C, Dunn LA, Dvorkin MV, De Beukelaer S, Pavlov D, Thurm H, Cohen E. Avelumab plus standard-of-care chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):450–462. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tree AC, Jones K, Hafeez S, Sharabiani MTA, Harrington KJ, Lalondrelle S, Ahmed M, Huddart RA. Dose-limiting urinary toxicity with pembrolizumab combined with weekly hypofractionated radiation therapy in bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(5):1168–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagodinsky JC, Harari PM, Morris ZS. The promise of combining radiation therapy with immunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaes RDW, Hendriks LEL, Vooijs M, De Ruysscher D. Biomarkers of radiotherapy-induced immunogenic cell death. Cells. 2021 doi: 10.3390/cells10040930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, Benci JL, Xu B, Dada H, Odorizzi PM, Herati RS, Mansfield KD, Patsch D, Amaravadi RK, Schuchter LM, Ishwaran H, Mick R, Pryma DA, Xu X, Feldman MD, Gangadhar TC, Hahn SM, Wherry EJ, Vonderheide RH, Minn AJ. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520(7547):373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, Yang X, Burnette B, Arina A, Li XD, Mauceri H, Beckett M, Darga T, Huang X, Gajewski TF, Chen ZJ, Fu YX, Weichselbaum RR. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(5):843–852. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang H, Deng L, Hou Y, Meng X, Huang X, Rao E, Zheng W, Mauceri H, Mack M, Xu M, Fu YX, Weichselbaum RR. Host STING-dependent MDSC mobilization drives extrinsic radiation resistance. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1736. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilones KA, Charpentier M, Garcia-Martinez E, Daviaud C, Kraynak J, Aryankalayil J, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Radiotherapy cooperates with IL15 to induce antitumor immune responses. Cancer Immunol Res. 2020;8(8):1054–1063. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niknam S, Barsoumian HB, Schoenhals JE, Jackson HL, Yanamandra N, Caetano MS, Li A, Younes AI, Cadena A, Cushman TR, Chang JY, Nguyen QN, Gomez DR, Diab A, Heymach JV, Hwu P, Cortez MA, Welsh JW. Radiation followed by OX40 stimulation drives local and abscopal antitumor effects in an anti-PD1-resistant lung tumor model. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(22):5735–5743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belcaid Z, Phallen JA, Zeng J, See AP, Mathios D, Gottschalk C, Nicholas S, Kellett M, Ruzevick J, Jackson C, Albesiano E, Durham NM, Ye X, Tran PT, Tyler B, Wong JW, Brem H, Pardoll DM, Drake CG, Lim M. Focal radiation therapy combined with 4–1BB activation and CTLA-4 blockade yields long-term survival and a protective antigen-specific memory response in a murine glioma model. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez I, Mayorga L, Labiano T, Barbes B, Etxeberria I, Ponz-Sarvise M, Azpilikueta A, Bolanos E, Sanmamed MF, Berraondo P, Calvo FA, Barcelos-Hoff MH, Perez-Gracia JL, Melero I. TGF beta blockade enhances radiotherapy abscopal efficacy effects in combination with anti-PD1 and anti-CD137 immunostimulatory monoclonal antibodies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(3):621–631. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiao JC, Bowers N, Nasti TH, Khosa F, Khan MK. 4–1BB (CD137) and radiation therapy: a case report and literature review. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2017;2(3):398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, Beckett M, Sharma R, Chin R, Tu T, Weichselbaum RR, Fu YX. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood. 2009;114(3):589–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arina A, Beckett M, Fernandez C, Zheng W, Pitroda S, Chmura SJ, Luke JJ, Forde M, Hou Y, Burnette B, Mauceri H, Lowy I, Sims T, Khodarev N, Fu YX, Weichselbaum RR. Tumor-reprogrammed resident T cells resist radiation to control tumors. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3959. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11906-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eberhardt CS, Kissick HT, Patel MR, Cardenas MA, Prokhnevska N, Obeng RC, Nasti TH, Griffith CC, Im SJ, Wang X, Shin DM, Carrington M, Chen ZG, Sidney J, Sette A, Saba NF, Wieland A, Ahmed R. Functional HPV-specific PD-1(+) stem-like CD8 T cells in head and neck cancer. Nature. 2021;597(7875):279–284. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03862-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitmire JK, Asano MS, Kaech SM, Sarkar S, Hannum LG, Shlomchik MJ, Ahmed R. Requirement of B cells for generating CD4+ T cell memory. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):1868–1876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M, Janeway C. Janeway's immunobiology. 8. New York: Garland Science; 2012. pp. 868–874. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrera FG, Ronet C, Ochoa de Olza M, Barras D, Crespo I, Andreatta M, Corria-Osorio J, Spill A, Benedetti F, Genolet R, Orcurto A, Imbimbo M, Ghisoni E, Navarro Rodrigo B, Berthold DR, Sarivalasis A, Zaman K, Duran R, Dromain C, Prior J, Schaefer N, Bourhis J, Dimopoulou G, Tsourti Z, Messemaker M, Smith T, Warren SE, Foukas P, Rusakiewicz S, Pittet MJ, Zimmermann S, Sempoux C, Dafni U, Harari A, Kandalaft LE, Carmona SJ, Dangaj Laniti D, Irving M, Coukos G. Low-dose radiotherapy reverses tumor immune desertification and resistance to immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(1):108–133. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franiak-Pietryga I, Miyauchi S, Kim SS, Sanders PD, Sumner W, Zhang L, Mundt AJ, Califano JA, Sharabi AB. Activated B cells and plasma cells are resistant to radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;112(2):514–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SS, Shen S, Miyauchi S, Sanders PD, Franiak-Pietryga I, Mell L, Gutkind JS, Cohen EEW, Califano JA, Sharabi AB. B cells improve overall survival in HPV-associated squamous cell carcinomas and are activated by radiation and PD-1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(13):3345–3359. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwon BS, Weissman SM. cDNA sequences of two inducible T-cell genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(6):1963–1967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi Y, Shi Y, Haymaker CL, Naing A, Ciliberto G, Hajjar J. T-cell agonists in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cannons JL, Lau P, Ghumman B, DeBenedette MA, Yagita H, Okumura K, Watts TH. 4–1BB ligand induces cell division, sustains survival, and enhances effector function of CD4 and CD8 T cells with similar efficacy. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1313–1324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menk AV, Scharping NE, Rivadeneira DB, Calderon MJ, Watson MJ, Dunstane D, Watkins SC, Delgoffe GM. 4–1BB costimulation induces T cell mitochondrial function and biogenesis enabling cancer immunotherapeutic responses. J Exp Med. 2018;215(4):1091–1100. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teijeira A, Labiano S, Garasa S, Etxeberria I, Santamaria E, Rouzaut A, Enamorado M, Azpilikueta A, Inoges S, Bolanos E, Aznar MA, Sanchez-Paulete AR, Sancho D, Melero I. Mitochondrial morphological and functional reprogramming following CD137 (4–1BB) costimulation. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(7):798–811. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melero I, Shuford WW, Newby SA, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE, Mittler RS, Chen L. Monoclonal antibodies against the 4–1BB T-cell activation molecule eradicate established tumors. Nat Med. 1997;3(6):682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buchan SL, Dou L, Remer M, Booth SG, Dunn SN, Lai C, Semmrich M, Teige I, Martensson L, Penfold CA, Chan HTC, Willoughby JE, Mockridge CI, Dahal LN, Cleary KLS, James S, Rogel A, Kannisto P, Jernetz M, Williams EL, Healy E, Verbeek JS, Johnson PWM, Frendeus B, Cragg MS, Glennie MJ, Gray JC, Al-Shamkhani A, Beers SA. Antibodies to Costimulatory Receptor 4–1BB Enhance Anti-tumor Immunity via T Regulatory Cell Depletion and Promotion of CD8 T Cell Effector Function. Immunity. 2018;49(5):958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finney HM, Akbar AN, Lawson AD. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J Immunol. 2004;172(1):104–113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, Carroll RG, Binder GK, Teachey D, Samanta M, Lakhal M, Gloss B, Danet-Desnoyers G, Campana D, Riley JL, Grupp SA, June CH. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1453–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Innamarato P, Asby S, Morse J, Mackay A, Hall M, Kidd S, Nagle L, Sarnaik AA, Pilon-Thomas S. Intratumoral activation of 41BB costimulatory signals enhances CD8 T cell expansion and modulates tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2020;205(10):2893–2904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Futagawa T, Akiba H, Kodama T, Takeda K, Hosoda Y, Yagita H, Okumura K. Expression and function of 4–1BB and 4–1BB ligand on murine dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14(3):275–286. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang B, Zhang Y, Niu L, Vella AT, Mittler RS. Dendritic cells and Stat3 are essential for CD137-induced CD8 T cell activation-induced cell death. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4770–4778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Voskens CJ, Sallin M, Maniar A, Montes CL, Zhang Y, Lin W, Li G, Burch E, Tan M, Hertzano R, Chapoval AI, Tamada K, Gastman BR, Schulze DH, Strome SE. CD137 promotes proliferation and survival of human B cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(2):787–795. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwarz H, Valbracht J, Tuckwell J, von Kempis J, Lotz M. ILA, the human 4–1BB homologue, is inducible in lymphoid and other cell lineages. Blood. 1995;85(4):1043–1052. doi: 10.1182/blood.V85.4.1043.bloodjournal8541043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biswas S, Mandal G, Payne KK, Anadon CM, Gatenbee CD, Chaurio RA, Costich TL, Moran C, Harro CM, Rigolizzo KE, Mine JA, Trillo-Tinoco J, Sasamoto N, Terry KL, Marchion D, Buras A, Wenham RM, Yu X, Townsend MK, Tworoger SS, Rodriguez PC, Anderson AR, Conejo-Garcia JR. IgA transcytosis and antigen recognition govern ovarian cancer immunity. Nature. 2021;591(7850):464–470. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabrita R, Lauss M, Sanna A, Donia M, Skaarup Larsen M, Mitra S, Johansson I, Phung B, Harbst K, Vallon-Christersson J, van Schoiack A, Lovgren K, Warren S, Jirstrom K, Olsson H, Pietras K, Ingvar C, Isaksson K, Schadendorf D, Schmidt H, Bastholt L, Carneiro A, Wargo JA, Svane IM, Jonsson G. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature. 2020;577(7791):561–571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, Thakur R, Yizhak K, Sade-Feldman M, Blando J, Han G, Gopalakrishnan V, Xi Y, Zhao H, Amaria RN, Tawbi HA, Cogdill AP, Liu W, LeBleu VS, Kugeratski FG, Patel S, Davies MA, Hwu P, Lee JE, Gershenwald JE, Lucci A, Arora R, Woodman S, Keung EZ, Gaudreau PO, Reuben A, Spencer CN, Burton EM, Haydu LE, Lazar AJ, Zapassodi R, Hudgens CW, Ledesma DA, Ong S, Bailey M, Warren S, Rao D, Krijgsman O, Rozeman EA, Peeper D, Blank CU, Schumacher TN, Butterfield LH, Zelazowska MA, McBride KM, Kalluri R, Allison J, Petitprez F, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C, Hacohen N, Rezvani K, Sharma P, Tetzlaff MT, Wang L, Wargo JA. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature. 2020;577(7791):549–555. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1922-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown DM, Fisher TL, Wei C, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Tumours can act as adjuvants for humoral immunity. Immunology. 2001;102(4):486–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gregg RK. Model Systems for the Study of Malignant Melanoma. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2265:1–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1205-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore MW, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Introduction of soluble protein into the class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. Cell. 1988;54(6):777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanpouille-Box C, Alard A, Aryankalayil MJ, Sarfraz Y, Diamond JM, Schneider RJ, Inghirami G, Coleman CN, Formenti SC, Demaria S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15618. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perez BA, Kim S, Wang M, Karimi AM, Powell C, Li J, Dilling TJ, Chiappori A, Latifi K, Rose T, Lannon A, MacMillan G, Saller J, Grass GD, Rosenberg S, Gray J, Haura E, Creelan B, Tanvetyanon T, Saltos A, Shafique M, Boyle TA, Schell MJ, Conejo-Garcia JR, Antonia SJ. Prospective single-arm phase 1 and 2 Study: ipilimumab and Nivolumab with thoracic radiation therapy after platinum chemotherapy in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109(2):425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharabi AB, Nirschl CJ, Kochel CM, Nirschl TR, Francica BJ, Velarde E, Deweese TL, Drake CG. Stereotactic radiation therapy augments antigen-specific PD-1-mediated antitumor immune responses via cross-presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(4):345–355. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clement LT. Isoforms of the CD45 common leukocyte antigen family: markers for human T-cell differentiation. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00918266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsumura S, Wang B, Kawashima N, Braunstein S, Badura M, Cameron TO, Babb JS, Schneider RJ, Formenti SC, Dustin ML, Demaria S. Radiation-induced CXCL16 release by breast cancer cells attracts effector T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3099–3107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee YH, Yu CF, Yang YC, Hong JH, Chiang CS. Ablative radiotherapy reprograms the tumor microenvironment of a pancreatic tumor in favoring the immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms22042091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Diamond JM, Vanpouille-Box C, Spada S, Rudqvist NP, Chapman JR, Ueberheide BM, Pilones KA, Sarfraz Y, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Exosomes shuttle TREX1-sensitive IFN-stimulatory dsDNA from irradiated cancer cells to DCs. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(8):910–920. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1(Supplementary Figure 1 Radiation-induced changes in CD8+ T cells at irradiated tumor sites, spleen, and irradiated draining lymph nodes of mice. (A) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrating no change in antigen exposed CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells at the irradiated tumor site compared to unirradiated control cohort. (B) slight increase in CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells in the peripheral spleen (C) no change in CD8+CD44+ T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells is observed in the irradiated draining lymph nodes in B16-OVA mouse model described in Figure 1A. (D) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrating no significant increase in peripheral blood antigen-exposed CD8+CD45RA- memory T cells as a percent of CD8+ T cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare Pre-RT and Post-RT time points across the study cohort) (TIF 24441 KB)

Supplementary file2 (Supplementary Figure 2 4-1BB upregulation in peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets following thoracic RT (A-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating increased % of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg (Treg=CD4+CD25+CD127-) CD4+ T cells as a percent of non-Treg CD4+ T cells after RT in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (A-right) Composite flow cytometry analysis demonstrating significant absolute changes from baseline of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg CD4+ T cells following RT following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. (B-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ peripheral Tregs (CD4+CD25+CD127-) in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (B-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change from baseline of 4-1BB+ peripheral non-Treg CD4+ T cells following RT. (C-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ B cells in a patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (C-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change of 4-1BB+ peripheral B cells as a percent of total B cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. (D-left) Flow cytometry analyses demonstrating no change in 4-1BB+ CD8+ T cells as a percent of total CD8+ T cells in a representative patient with extensive stage small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT on clinical trial as described in Figure 2D. (D-right) Composite analysis demonstrating no change of 4-1BB+ peripheral 4-1BB+ CD8+ T cells as a percent of total CD8+ T cells following RT in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving thoracic RT as described in Figure 2D. Paired T test analyses of patient samples performed to compare Pre-RT and Post-RT time points across the study cohort) (TIF 22774 KB)

Supplementary file3 (Supplementary Figure 3 RT alone and RT with 4-1BB agonism control tumor growth at irradiated tumor sites. (A)B16-OVA tumor growth in right flank of untreated mice. (B) Tumor growth curve of irradiated flank tumors in mice receiving ablative RT as outlined in Figure 1A. (C) Tumor growth of irradiated flank tumors in mice receiving ablative RT with combination of CTX-471-AF. (D) Right flank tumor growth curves of untreated mice inoculated with 10^6 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells. (E) Tumor growth curve of irradiated tumor flanks of mice that received ablative (8Gy x 3) RT treatment directed at the right tumor flank. (F) Tumor growth curve of irradiated tumors of mice that received a combination of RT with CTX-471-AF) (TIF 10012 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.