Abstract

In this study, the effect of different moisture levels in extruded plant-based meat on macrophage immunostimulation, and the potential of this meat as a protein source and a solution to environmental and economic challenges associated with conventional meat was investigated. To determine the effects of the extruded plant-based meat, cell viability assay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, flow cytometry, and western blotting were performed. Low-moisture (LMME) and high-moisture meat extracts (HMME) showed higher potential to activate macrophages and regulate cytokine production than raw material extract. Treatment with LMME and HMME resulted in increased expression of CD80, CD86, and MHC class I/II proteins, indicating their potential to activate macrophages. Western blotting suggested that the immune activation observed in a previous study of macrophages was because of the phosphorylation of MAPKs and NF-κB. These findings suggest that extruded plant-based meat can potentially be used as an immunostimulatory food ingredient.

Keywords: Immunological activity, Extrusion, Plant-based meat, Macrophage activation, NF-κB

Introduction

Immunomodulation is the process by which the immune system defends itself against infections, diseases, or other harmful stimuli (Cooper and Alder, 2006). The immune system consists of innate and adaptive subsystems. Macrophages, which are involved in innate and adaptive immunity, play a crucial role as components of the first line of defense by removing infectious pathogens and activating adaptive immunity (Murray and Wynn, 2011). When macrophages are stimulated by pathogens, they produce various immunostimulatory factors, including nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Möller and Villiger, 2006). In addition, macrophages express antigen-presenting proteins such as cluster of differentiation (CD)80/86 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I/II (Murray et al., 2014). Ultimately, macrophage activation leads to the modulation of adaptive immunity by activating antigen-specific adaptive immune cells such as T- and B-lymphocytes (Wculek et al., 2020). Therefore, macrophages are a critical immune cell population located at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity, and their activation serves as a key indicator of immune response (Smith et al., 2016). Recently, there has been increasing interest in the development of natural health functional foods for immunocompromised individuals, particularly elderly individuals and patients with cancer (Song et al., 2021). Studies in this field have focused on enhancing immune function by regulating innate immune responses via macrophage activation.

As concerns about global warming, climate change, and food security continue to grow, alternative meats, including edible insects and plant-based meats, have emerged as promising substitutes for conventional meat products (Springmann et al., 2018). “Extruded plant-based meat" is an alternative meat product produced by subjecting plant-based ingredients to extrusion molding, resulting in a food product with a texture and appearance similar to that of meat (Jeon et al., 2022). Extruded plant-based meat can be classified into two major types based on moisture content, namely, low (< 50% moisture) and high moisture (> 50% moisture) (Gu and Ryu, 2017). The moisture content affects the textural properties and solubility index of nitrogen in extruded plant-based meat (Choi and Ryu, 2022). Recently, there has been active research on extruded plant-based meat, in terms of not only its physical and physicochemical characteristics, but also its nutritional benefits and physiological activities (Abdullah et al., 2022). However, there are no reports on the immunomodulatory effects of extruded plant-based meat. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate whether plant-based meat produced using high- and low-moisture extrusion molding exhibits immunomodulatory effects on immune cells compared to raw materials. The results of this study could provide insights into the nutritional value of extruded plant-based meats and the nutritional impact of processing methods.

Materials and methods

Raw material water extract

The raw materials used in this study were a combination of isolated soy protein (Pingdingshan TianJing Plant Albumnen Co., Henan, China), wheat gluten (Roquette Freres, Lestrem, France), and corn starch (Samyang Corp., Ulsan, Korea) at a ratio of 5:4:1. To extract the water-soluble components, 30 g of the powder was soaked in 600 mL of distilled water and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. The extracts were then centrifuged at 21,331×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting clear supernatant was freeze-dried. The freeze-dried raw material extract (RME) was then dissolved in distilled water, used for cell treatment, and stored at − 80 °C for later use.

Low- and high-moisture extruded plant-based meat extract

Extrusion was performed using a THK31-No.5 machine (Incheon Machinery Co., Incheon, Korea). The low-moisture extrusion conditions were as follows: moisture content, 25–40%; temperature, 150 °C; and screw speed, 250 rpm. The high-moisture extrusion conditions were as follows: moisture content, 55–70%; temperature, 160 °C; and screw speed, 150 rpm. Thirty grams of low–high-moisture extruded plant-based meat powder was soaked in 600 mL of distilled water at 4 °C for 24 h. The resulting extracts were then centrifuged at 21,331×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the clear supernatant was freeze-dried. The low-moisture meat extract (LMME) and high-moisture meat extract (HMME) were then stored at − 80 °C.

Cell line and culture condition

The murine macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7, was obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). The cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Welgene, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, from Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-enriched, humid environment and subcultured weekly.

Macrophage viability assay

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After allowing the cells to attach for 24 h, they were treated with the plant-based meat aqueous extract. At the end of the treatment period, 20 μL of MTT reagent (5 mg/mL) was added to each well. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. After removing the supernatant, formazan crystals formed were dissolved in 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide and gently agitated at 37 °C for 10 min. Finally, the absorbance of sample in each well was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

Measurement of nitric oxide (NO) production

The experimental RAW 264.7 cell culture supernatants were collected and stored at − 70 °C until further use. The amount of nitrite in the culture supernatants was determined by quantifying the oxidation product nitrite using the Griess method (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Briefly, 100 μL of the culture supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (0.1% naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 2.5% phosphoric acid and 1% sulfanilamide). The reaction mixture was then incubated at 20–25 °C for an additional 10 min. Finally, the absorbance of the sample was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader.

Measurement of cytokine production

Supernatants from the experimental RAW 264.7 cell cultures were collected and stored at –70 °C until use. The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the cell culture supernatant were measured using a cytokine detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (eBioscience Co., San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Detection was performed at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Measurement of cell surface molecules using flow cytometry

The expression of activation markers in macrophages was analyzed using flow cytometry. After treatment, the RAW 264.7 cells were washed twice with 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in washing buffer consisting of 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide in PBS. The cells were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Before analysis, the cells were incubated with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 1 × PBS for 30 min and then washed with 1 × PBS. The cells were then stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse MHC I, MHC II, fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC) hamster anti-mouse CD80, or FITC rat anti-mouse CD86 (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) antibodies for 45 min at 4 °C. After staining with specific antibodies, the cells were washed with cold PBS and centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min.

Western blotting

The harvested cells were washed twice with 1 × PBS. Total protein was extracted from the cells using RIPA buffer (Rockford, IL, USA) and quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were denatured by boiling in the sample buffer for 5 min at 100 °C. The denatured proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) at 90 V for 50 min using a transfer buffer. The membranes were then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1 × Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at room temperature for 1 h to prevent nonspecific antibody responses. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight with specific primary antibodies at 4 °C. The membranes were washed for 1 h with 1 × TBS buffer and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the membranes were washed again for 1 h with 1 × TBS buffer and detected using an electrochemiluminescence reagent (Millipore Merck KGaA).

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated using GraphPad Prism (version 8; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare differences among multiple groups, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 per group). Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to the negative control (NC) group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 compared to the RME-treated group.

Results and discussion

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on the viability of macrophages

RAW 264.7 cells were treated with RME, LMME, and HMME at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL. The cells treated with 0.2 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and 500 and 1000 μg/mL chicken extract (CE) were used as positive controls (PCs). After 24 h, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 1, the extract did not exhibit any toxicity at concentrations ranging from 500 to 1000 μg/mL in RAW 264.7 cells.

Fig. 1.

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells). We evaluated the viability of RAW 264.7 cells treated with raw material extract (RME), and low-moisture (LMME) and high-moisture meat extracts (HMME) at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL, as well as with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 200 ng/mL as a positive control (PC). Cells were treated with chicken extract (CE) at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL. After 24 h, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. The data were presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 per group). Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the negative control (NC) group

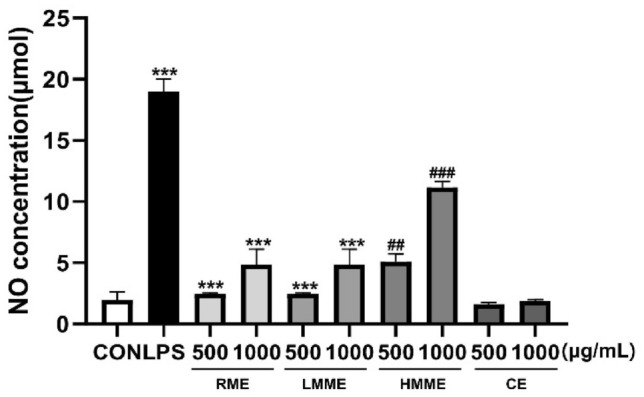

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on the secretion of NO

NO secretion induced by macrophages plays a vital role in regulating the death of infected and cancer cells and protecting the body against antigens (Banuls et al., 2014). Moreover, NO secretion, along with cytokine secretion, serves as an indicator of macrophage-mediated immune activation (Kashfi et al., 2021). To investigate the effects of the extruded plant-based meat and its raw materials on macrophage activity, we measured NO production. We treated cells with RME, LMME, HMME, and CE at 500 and 1000 μg/mL for 24 h, whereas cells treated with LPS at 200 ng/mL was used as the PC. NO in the culture supernatant was quantified using the NO assay. All extracts and the PC significantly increased NO production compared to the NC. In particular, HMME induced higher NO production than RME or LMME at the same concentration (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that extruded plant-based meat effectively induces NO secretion and that HMME activates RAW 264.7 cells compared to RME.

Fig. 2.

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on NO production activity of macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells). RAW 264.7 cells were treated with RME, LMME, and HMME at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL, as well as with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 200 ng/mL as a PC. Cells were treated with chicken extract (CE) at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL. After 24 h, NO production in the culture supernatant was measured using the Griess assay. The results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3) and analyzed using the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the NC group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001, compared to the RME-treated group

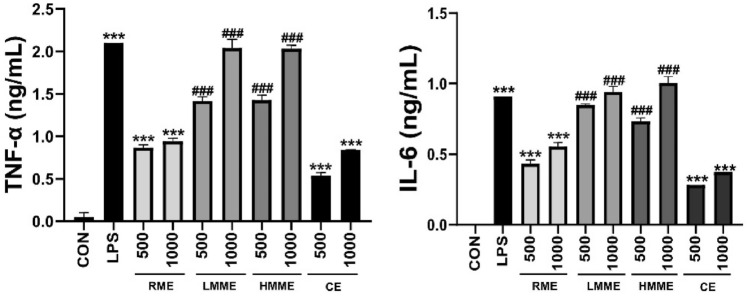

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion

The signaling pathways of TNF-α and IL-6 play a critical role in the immune response of macrophages (Möller and Villiger, 2006). TNF-α secretion increases during macrophage activation and antigen processing, ultimately inducing the activation and proliferation of T cells (Francisco et al., 2015). Subsequently, IL-6 generates memory dendritic cells that arise after antigen processing, activates them, or induces the maturation of B cells, thereby contributing to an effective immune response against infections and malignancies (Janssens et al., 2010). The levels of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 are a crucial indicator of macrophage activation (Byun, 2015). Thus, quantification of these cytokines has been widely used as a crucial tool to assess the activity of macrophages in response to antigens or other stimuli (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on cytokine (TNF-α and IL-6) production activity of macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells). RAW 264.7 cells were treated with RME, LMME, and HMME at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL, as well as with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 200 ng/mL as a PC. Cells were treated with chicken extract (CE) at concentrations of 500 and 1000 μg/mL. After 24 h, cytokine production in the culture supernatant was measured using ELISA. The results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3) and analyzed using the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the NC group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001, compared to the RME-treated group

First, we investigated whether extruded meat extract could induce macrophage activity and, consequently, regulate cytokine production. The cells were treated with RME, LMME, HMME, and CE at 500 and 1000 μg/mL for 24 h, and the cytokines in the supernatants were quantified using ELISA. As PCs, the cells were treated with LPS, which activates macrophages (Guha and Mackman, 2001), at 200 ng/mL. The production of TNF-α and IL-6 in RAW 264.7 cells was significantly enhanced by all meat extracts and CE. In particular, the extruded meat extracts, LMME and HMME, at the same treatment concentration, induced a higher level of cytokine production than the RME. TNF-α and IL-6 are pleotropic cytokines in the immune system that, when overproduced, can be major contributors to the development of inflammatory diseases, but they are also essential in eliminating harmful antigens, for example, in anti-tumor and anti-viral responses (Montfort et al., 2019; Velazquez-Salinas et al., 2019). Our results indicate that extruded meat extracts have greater potential to induce cytokine production in macrophages than raw meat extracts. We speculate that extruded meat extracts may be more effective than raw meat extracts in immunosuppressive conditions, but further research using experimental models, such as tumor-bearing and influenza A-infected mouse models, is required.

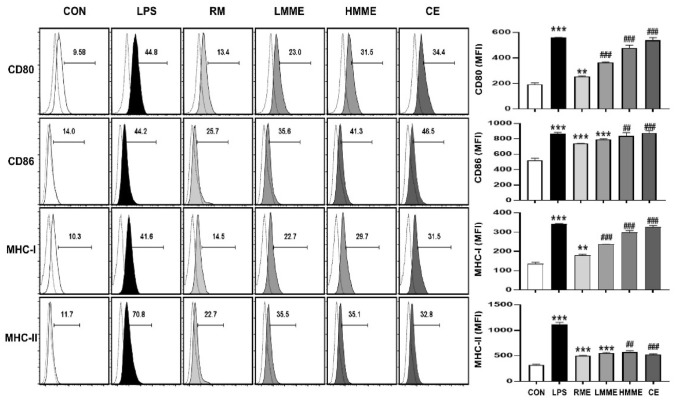

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on surface activation of macrophages

The expression of representative molecules such as CD80 and CD86 on macrophages is essential for initiating adaptive immunity, as they play a vital role in promoting T cell activation by presenting antigens to antigen-presenting cells (Sansom et al., 2003). Furthermore, MHCs play a central role in the function of antigen-presenting cells, with dendritic cells activating CD8+ T cells via MHC class I (Van Kaer et al., 2019) and promoting antigen presentation and activation of CD4+ T cells via MHC class II (Crotzer and Blum, 2009). To investigate whether the extruded plant-based meat extract could activate dendritic cells, we observed the expression of CD80, CD86, MHC class I, and MHC class II in RAW 264.7 cells. Treatment with LMME and HMME at 1000 μg/mL resulted in higher expression of CD80, with increases of 9.6% and 22.1%, respectively, compared to treatment with RME. The groups treated with LMME and HMME at 1000 μg/mL showed higher expression of CD86, with increases of 9.9% and 15.6%, respectively, than the RME group. The groups treated with LMME and HMME at 1000 μg/mL showed higher MHC class I expression, with increases of 8.2% and 15.2%, respectively, than the RME group. The groups treated with LMME and HMME at 1000 μg/mL showed higher MHC class II expression, with increases of 12.8% and 12.7%, respectively, than the RME group. Similar to the results of NO and cytokine secretion in the previous experiments, the LMME and HMME groups showed higher expression of surface markers than the RME group. This finding suggests that the raw materials induced macrophage activation more effectively after extrusion molding. Lin et al. (2008) and Gao et al. (2022) demonstrated that the phosphorylation activity, dissociation bonding, and hydrogen bonding of proteins can be influenced by moisture content during the extrusion of plant-based meat. Specifically, a higher moisture content can increase protein solubility and soluble nitrogen content. These findings suggest that protein denaturation induced by high moisture content during extrusion could have a more potent effect on macrophage activation, potentially explaining the significantly higher expression of CD80 and MHC class I in the HMME group than in the LMME group observed in the present study. This finding suggests that plant-based extracts have the potential to modulate immune activity and provides insights into the mechanisms underlying these effects (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on surface molecules in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with RME, LMME, and HMME at 1000 μg/mL, as well as with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 200 ng/mL as a PC. Cells were treated with chicken extract (CE) at concentrations of 1000 μg/mL. After 24 h, cells were stained with anti-CD80/86 and anti-MHC-I/II for 30 min. Surface marker expression was measured using a flow cytometer. The results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3) and analyzed using the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the NC group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001, compared to the RME-treated group

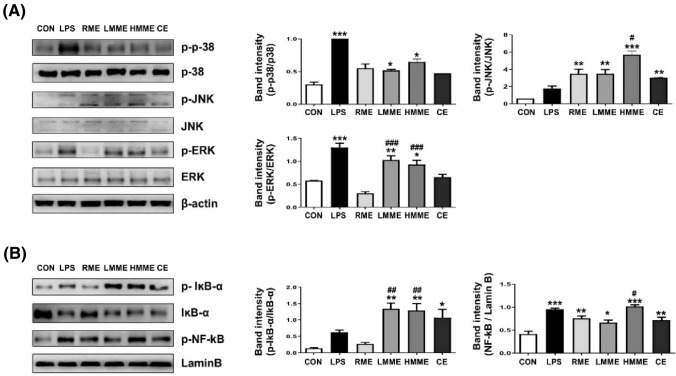

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)

Macrophages are activated through a complex cascade of processes, including the phosphorylation of MAPKs such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38, as well as the transcriptional activation of NF-κB (Hong et al., 2022). While NF-κB acts as a critical regulator of antigen presentation and immune response, MAPKs promote the immune response by inducing cytokine secretion in macrophages (Han et al., 2021). Following macrophage activation, IκB is phosphorylated and degraded, leading to the activation of NF-κB, which translocates to the nucleus and induces immune responses via gene transcription (Annemann et al., 2016). To elucidate the mechanism by which extruded plant-based meat extracts activate macrophages, we investigated whether this process involves the phosphorylation of MAPKs and NF-κB. The phosphorylation levels of MAPKs and NF-κB were examined in RAW 264.7 cells treated with 1000 μg/mL RME, LMME, HMME, and CE. The RME-treated group showed a significantly higher level of JNK phosphorylation than the control group, whereas the LMME- and HMME-treated groups showed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of p38, JNK, and ERK compared to the NC group (Fig. 5(A)). We also measured the phosphorylation of IκB and NF-κB, which are involved in the regulation of inflammation. The RME-treated group did not show a significant difference in IκB phosphorylation compared to the NC group, whereas the LMME- and HMME-treated groups exhibited a significant increase in IκB phosphorylation. Furthermore, all treatment groups showed a significantly higher level of NF-κB phosphorylation than the NC group (Fig. 5(B)). These findings reveal a trend similar to the previously reported effects of augmented secretion of NO and cytokines as well as upregulated expression of cell surface molecules in macrophages. It is plausible that these effects are modulated by MAPKs and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Fig. 5.

Effect of extruded plant-based meat extract on MAPK and NF-kB signals in macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells). RAW 264.7 cells were treated with RME, LMME, and HMME at 1000 μg/mL, as well as with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) at 200 ng/mL as a PC. Cells were treated with chicken extract (CE) at concentrations of 1000 μg/mL. After 24 h, cells were stained with anti-CD80/86 and anti-MHC-I/II for 30 min. Surface marker expression was measured using a flow cytometer. Activation of (A) MAPKs (phosphorylated ERK, JNK, and p38) and (B) NF-κB (phosphorylated IκB-α and IκB-α, and degradation and nuclear translocation of p65) signals were analyzed using western blotting. Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, compared to the NC group, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001, compared to the RME treated group

In conclusion, extruded plant-based meat extracts were not cytotoxic and effectively induced NO secretion and cytokine production in RAW 264.7 cells. Notably, LMME and HMME extracted from extruded meat exhibited greater potential to activate macrophages and induce cytokine production than RME. Furthermore, treatment with LMME and HMME resulted in increased expression of CD80, CD86, MHC class I, and MHC class II proteins, indicating their potential to activate macrophages. The western blot analysis results suggested that the immune activation observed in a previous study of macrophages was because of the phosphorylation of MAPKs and NF-κB. Alternative meat undergoes various transformations during the extrusion process, including unfolding, association, cohesion, and potential degradation or cross-linking due to oxidation (Zhang et al., 2018). The observed effects can be ascribed to alterations in protein phosphorylation activity, dissociation, and hydrogen bonding resulting from the extrusion process, with variations observed depending on the moisture content (Lin et al., 2008). Lin et al. (2022) reported that the extrusion process of alternative meat exposes hydrophilic matrices and glassy thiol groups, thereby promoting interactions among various molecules and resulting in elevated levels of free amino acids during digestion. On the contrary, gluten, known for its insolubility and poor digestibility, shows a substantial increase in fiber spacing and reduced cohesion as a result of the extrusion process, leading to enhanced digestibility and improved protein solubility (Zhang et al., 2018). Similarly, extrusion leads to an increase in the nitrogen solubility index of the raw material, and this has been found to be directly proportional to the moisture content of alternative meat (Gao et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2017). On the basis of the findings of these previous studies, it appears that extrusion plays a role in activating macrophages by facilitating molecular interactions through the modification of the major protein components present in alternative meat. Overall, these findings suggest that extruded plant-based meat extracts exert immunomodulatory effects on macrophages, which may contribute to their potential health benefits. However, further studies are required to determine the conditions that affect macrophage activation during protein denaturation caused by extrusion molding and to verify these findings under specific conditions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (No. NRF-2022R1F1A1063850).

Author contributions

Concept and design: BEH. Analysis and interpretation: HJP. Data collection: HJP. Writing the article: Hong JP. Critical revision of the article: BEB, RGH, SHY. Final approval of the article: all authors. Statistical analysis: YBG, SHY. Obtained funding: BEH. Overall responsibility: BEH.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors of this study have any financial interest or conflict with industries or parties. All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdfullah FAA, Dordevic D, Kabourkova E, Zemancova J, Dordevic S. Antioxidant and sensorial properties: Meat analogues versus conventional meat products. Processes. 2022;10:1864. doi: 10.3390/pr10091864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annemann M, Plaza-Sirvent C, Schuster M, Katsoulis-Dimitriou K, Kliche S, Schraven B, Schmitz I. Atypical IκB proteins in immune cell differentiation and function. Immunology letter. 2016;171:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuls C, Rocha M, Rovira-Llopis S, Falcon R, Castello R, Herance JR, Polo M, Blas-Garcia A, Hernandez-Mijares A, Victor MV. The pivotal role of nitric oxide: effects on the nervous and immune systems. Current pharmaceutical design. 2014;20:4679–4689. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140130213510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun EH. Comparison study of immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharide and ethanol extracted from Sargassum fulvellum. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2015;44:1621–1628. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2015.44.11.1621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HW, Ryu GH. Comparison of the physicochemical properties of low and high-moisture extruded meat analog with varying moisture content. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2022;51:162–169. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2022.51.2.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copper MD, Alder MN. The evolution of adaptive immune systems. Cell. 2006;124:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotzer VL, Blum JS. Autophagy and its role in MHC-mediated antigen presentation. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:3335–3341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco NM, Hsu NJ, Keeton R, Randall P, Sebesho B, Allie N, Govender D, Quesniaux V, Ryffel B, Kellaway L, Jacobs M. TNF-dependent regulation and activation of innate immune cells are essential for host protection against cerebral tuberculosis. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:125. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0345-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Jin T. Extrusion modification: Effect of extrusion on the functional properties and structure of rice protein. Processes. 2022;10:1871. doi: 10.3390/pr10091871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu BY, Ryu GH. Effects of moisture content and screw speed on physical properties of extruded soy protein isolate. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2017;46:751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cellular Signalling. 2001;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JM, Song HY, Lim ST, Kim KI, Seo HS, Byun EB. Immunostimulatory potential of extracellular vesicles isolated from an edible plant, Petasites japonicus, via the induction of murine dendritic cell maturation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22:10634. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JP, Yoo BG, Lee JH, Song HY, Byun EH. Immunostimulatory activity of Allomyrina dichotoma larva extract through the activation of MAPK and the NF-κB signaling pathway in macrophage cells. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 2022;51:229–236. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2022.51.3.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens K, Slaets H, Hellings N. Immunomodulatory properties of the IL-6 cytokine family in multiple sclerosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1351:52–60. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon YH, Gu BJ, Ryu GH. Effect of yeast content on the physicochemical properties of low-moisture extruded meat analog. Journal of the Korean Society Food Science and Nutrition. 2022;51:271–277. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2022.51.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashfi K, Kannikal J, Nath N. Macrophage reprogramming and cancer therapeutics: Role of iNOS-derived NO. Cells. 2021;10:3194. doi: 10.3390/cells10113194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Huff HE, Hsieh F. Texture and chemical characteristics of soy protein meat analog extruded at high moisture. Food Chemistry and Toxicology. 2008;65:264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Pan L, Deng N, Sang M, Cai K, Chen C, Han J, Ye A. Protein digestibility of textured-wheat-protein (TWP)-based meat analogues: Effects of fibrous structure. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;130:107694. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montfort A, Colacios C, Levade T, Andrieu-Abadie N, Meyer N, Ségui B. The TNF paradox in cancer progression and immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;10:1818. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller B, Villiger PM. Inhibition of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Springer Seminars in Immunopathology. 2006;27:391–408. doi: 10.1007/s00281-006-0012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom DM, Manzotti CN, Zheng Y. What's the difference between CD80 and CD86? Trends in Immunology. 2003;24:314–319. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TD, Tse MJ, Read EL, Liu WF. Regulation of macrophage polarization and plasticity by complex activation signals. Integrative Biology (camb) 2016;8:946–955. doi: 10.1039/c6ib00105j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HY, Han JM, Byun EH, Kim WS, Seo HS, Byun EB. Bombyx batryticatus protein-rich extract induces maturation of dendritic cells and Th1 Polarization: A potential immunological adjuvant for cancer vaccine. Molecules. 2021;26:476. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springmann M, Clark M, Mason-D'Croz D, Wiebe K, Bodirsky BL, Lassaletta L, de Vries W, Vermeulen SJ, Herrero M, Carlson KM, Jonell M. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature. 2018;562:519–525. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kaer L, Parekh VV, Postoak JL, Wu L. Role of autophagy in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation. Molecular Immunology. 2019;113:2–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez-Salinas L, Verdugo-Rodriguez A, Rodriguez LL, Borca MV. The role of interleukin 6 during viral infections. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;10:1057. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li C, Wang B, Yang W, Luo S, Zhao Y, Jiang S, Mu D, Zheng Z. Formation of macromolecules in wheat gluten/starch mixtures during twin-screw extrusion: effect of different additives. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculturer. 2017;97:5131–5138. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wculek SK, Cueto FJ, Mujal AM, Melero L, Krummel MF, Sancho D. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020;20:7–24. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0210-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liu L, Liu H, Yoon A, Rizvi SSH, Wang Q. Changes in conformation and quality of vegetable protein during texturization process by extrusion. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2018;9:267–3280. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1487383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]