Abstract

Cyclic peptides can resist enzymatic hydrolysis to pass through the intestine barrier, which may reduce the risk of mild cognition decline. But evidence is lacking on whether they work by alleviating neuroinflammation. A cylic peptide from Annona squamosa, Cylic(PIYAG), was biologically evaluated in vivo and in vitro. Cylic(PIYAG) enhanced the spatial memory ability of LPS-induced mice. And treatment with Cylic(PIYAG) markedly reduced the iNOS, MCP-1, TNF-α, and gp91phox expression induced by LPS. Cylic(PIYAG, 0.01, 0.05 and 0.2 μM) could significantly reduce the protein expression level of COX-2 and iNOS (P < 0.05) in BV2 cells. The concentration of Cylic(PIYAG) in blood reached a peak of 3.64 ± 1.22 μg/ml after intragastric administration in 1 h. And fluorescence microscope shows that Cylic(PIYAG) mainly locates and may play an anti-inflammatory role in the cytoplasm of microglia. This study demonstrates that the peptidic can prevent microglia activation, decrease the inflammatory reaction, improve the cognition of LPS-induced mice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-023-01441-8.

Keywords: Cyclic peptide, Neuroinflammation, Cognitive impairment, Cytokine

Introduction

Neuroinflammation is the common pathogenic mechanism of many neurodegenerative diseases. Primary and secondary injuries of the central nervous system can lead to multiple aseptic injuries, and induce cell apoptosis, inflammatory response, neurological dysfunction, etc. Severe neuroinflammation is one of the important pathogenesis of many neurosystemic diseases, including depression, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Lashley et al., 2018), Parkinson's disease (PD) and other dementias. Recently, the cerebral renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been shown be a relationship with cognitive impairment or dementia (Torika et al., 2018; Wakita et al., 2010).

Increased ACE activity has been found in the brains of cognitive impairment patients (Evans et al., 2020), which first releases more angiotensin II (Ang II), produced by ACE hydrolysis (Crackower et al., 2002), and then Ang II can induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) by NADPH oxidase. Afterwards, the important transcription factors in multiple inflammatory pathways are activated. It is noteworthy that many studies have found that ACE inhibitors are beneficial to alleviate the cognitive decline of animals and patients (Lee et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2014; Quitterer and AbdAlla, 2020). Ohrui et al. reported that long-term use of central active ACE inhibitors can slow down the cognitive decline rate, and even has a protective effect on the occurrence of dementia (Lee et al., 2020; Ohrui et al., 2004; Quitterer and AbdAlla, 2020). Previous study also showed that peptides can slow down the cognitive decline in aging mice (Huang et al., 2019; Mann et al., 2017). However, natural peptide derived from Annona squamosa, Cylic(PIYAG) have been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo (Chuang et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2008), which also owns the tolerance to enzymolysis in gastrointestinal tract. This provides a new idea for the exploration of neuroinflammatory nutrients from food sources.

A large number of experiments (Caron et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2003) have proved that animals with a certain amount of peptide intake have a better performance in the evaluation of behavioral experiments. Due to cyclic peptides not only have hypotensive effects (Dang et al., 2019), but have a variety of physiological functions, including relief of neuroinflammation and inhibition of cognitive impairment (Dang et al., 2019; Edvinsson, 2002). However, can Cylic(PIYAG) also contribute to the recovery of cognitive function by alleviating neuroinflammation? It is still lacking in current studies.

Neuroinflammation plays a regulatory role in the central nervous system. It is a powerful contributor to triggering and exacerbating neurodegenerative changes, characterized by continuous activation of microglia. The activated pro-inflammatory transcription factors improve the cytokines and chemokines expression, which leads to the progress of inflammatory response and in turn generates more ROS (Sundaram and Bramhachari, 2017; Tucsek et al., 2017). Oxidative stress is closely related to inflammation. ROS usually can induce the upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes through the NF-κB pathway. Then more ROS in cells promotes mitochondrial dysfunction, aggravates cell damage. Oxidative stress and inflammatory response also play an important role in cognitive impairment associated with neuronal dysfunction (Tian et al., 2020). Therefore, the change of ROS has become a necessary indicator for the study of neuroinflammation.

The purpose of this study was to verify our hypothesis that cyclic peptides can prevent cognitive decline by alleviating neuroinflammation. And the effects of cyclic peptides on cognition and memory in LPS-induced mice were studied through a series of behavioral and physiological experiments. We aimed to highlight a promising candidate that may effectively regulate neuronal viability and functionality both in vivo and in vitro. Besides, this study demonstrates that the drug candidate of peptide can prevent microglia activation, decrease inflammatory reaction. What’s more, the effects of oral drug candidates on brain function in elderly mice also be discussed. Our findings may provide an intensive analysis of the role of this cyclic peptide, which may be a helpful to ameliorate cognitive impairment.

Materials and methods

Animals

Thirty 12-month-old ICR mice, half male and half female, weighing 48 ± 5 g, were collected from the experimental animal center of Hefei Medical University. The drinking water and feed were sterilized by high-temperature steam, and the feed was maintained by the purchased experimental mice. The mice were fed freely during the feeding period. The utensils and related facilities for animal breeding have passed the certification. The temperature of the animal room was 22 ~ 26 °C, the relative humidity was 60% ± 10%, and the animals were raised under 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. This study was carried out by the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, which is approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Anhui Medical University (AL2021001302).

Animal feeding and grouping by dose

The experimental mice were divided into 5 groups with 10 mice in each group. The mice were divided into 3 groups by gavage. The gavage doses were 0.1 g/(kg · d) and the groups were labeled as Cylic(PIYAG), respectively. The blank control group was sterilized with the same volume of distillation. The animals were reared adaptively for 5 days before the experiment, weighed once a week, adjusted the dosage, and gavaged for 6 weeks.

Morris water maze test

Morris water maze test (Chung et al., 2017; Higaki et al., 2018)was carried out at the 6th week after administration for 6 days, during which the mice were continuously given gastric peptide. Morris water maze includes positioning navigation experiment and space exploration experiment. The diameter of the round pool is 120 cm and the height of the pool is 55 cm. The water temperature is 23 ± 2 °C and the water depth is 26 cm. Different shapes of markers were pasted on the inner wall above the water surface to keep the indoor environment and furnishings unchanged during the experiment. The transparent platform, 8 cm in diameter, was placed 1 cm below the water surface in the center of the maze. The mice were tracked by a camera above the maze. Swimming training lasted for 5 days (the mice were allowed to swim for 90 s the day before). Mice were put into the pool from different quadrants facing the pool wall, once in each quadrant, a total of 4 times, with an interval of 10 min. the latency (s) of each time was recorded and the average value was calculated. Latency is the time it takes a mouse to find a platform. If the mice did not find the underwater platform within 60 s, they were guided to the platform for 10 s (the incubation period was recorded as 60 s). In the space exploration experiment, the underwater platform was removed after the positioning navigation experiment, and the number of mice crossing the platform in 60 s was recorded.

Biochemical index analysis

After the behavioral experiment, the mice were fasted for 12 h without water, and then the cervical spine was removed and sacrificed. The blood was collected, and the brain was quickly separated in an ice bath. The hippocampus was taken out of mice brain and was homogenized by adding normal saline, centrifuged for 10 min at 3 500 r/min, and the supernatant was collected and preserved. The level of Nittrite, IL-1, IL-6, MCP-1, TNF-α-in brain was measured according to the instructions of the kit. The Logistic parameter curve was fitted using ELISA data processing software for kit labeling.

Slice staining and immunohistochemical staining of brain tissue

After deep anesthesia, the mice were fixed by injecting 4% paraformaldehyde into the left ventricle of the heart, and then the brain was removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde and fixed for 48 h (at 4 °C). Conventional paraffin embedding was performed, and coronal continuous sections were performed for Himani staining and immunohistochemical staining. The sections of hippocampus were dried and then stained in 0.1% tar-purple solution at 37 °C for 5 min, then washed with distilled water. 95% alcohol differentiation, distilled water rinse; Gradient alcohol (70% → 80% → 90% → 95% I → 95% II → 100% I → 100% II) was dehydrated for 3 min each, xylene I and xylene II were transparent for 3 min each. The slice was sealed by neutral gum after the tissue HE staining. The changes of neuron morphology and number in hippocampal CA1 and CA3 were observed under the light microscope. Brain slice were observed under a 400× light microscope, with an area of 4.5 × 10–2 mm2 under the microscope. Motic data analysis software was used to count neurons, and the results were averaged. And the immunohistochemical staining of p-Caspase3 was adopted by prvious method with a minor modification (Sundaram et al., 2017).

Pharmacokinetics of Cylic(PIYAG) in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

Seven healthy male ICR mice were fed without water for 12 h before administration. Cylic(PIYAG) was given intragastric administration at the dose of 10 mL·kg−1, and blood was collected from the fundus venous plexus at 5,10,20,30,45 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h after administration, 0.1 mL each time in a 1.5 mL EP tube. The upper serum was separated by centrifugation at 3 500 r·min−1 for 15 min, and then cryopreserved at – 20 °C. The 20 μL mice serum samples were placed in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube and shaken by eddy for 0.5 min. Then 600 μL methanol was added and shaken in a vortex for 10 min. Then the supernatant was centrifuged at 13 200 r·min−1 for 10 min. The supernatant was concentrated and dried by vacuum centrifugation, then redissolved with 100 μL methanol, and put into a 250 μL intubated sample bottle, and 3 μL sample was injected.

The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium. The mouse head skin was disinfected and depilated, and the incision was made along the posterior midline (about 1 cm). Use hemostatic forceps to clamp the skin apart. Use flexion tweezers to tear the superficial muscle along the midline alba. The muscles deeply attached to the foramen magnum continue to be separated longitudes by forceps in the direction of the midline. Finally, the remaining muscle attached to the dura is removed with tweezers until the white dura is fully exposed. Using a micropipette, gently screw into the dura mater and drain 20 μL of CSF.

qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted by Trizol (Invitrogen) method, and RNA integrity was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration and purity of RNA were detected by micro UV–Vis spectrophotometer (DS-11, Denovix Inc, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit with GDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TAKARA), and the cDNA was stored in a refrigerator at − 20 °C for later use. The forward and reverse primers used were as follows: inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), 5′-GTCACCTACCGCACCCGAG-3′and 5′-GCCACTGACACTTCGCACAA3′; monocyte chemotactic and activating factor-1 (MCP-1), 5′-TTAACGCCCCACTCACCTGCTG-3′ and 5′-GCTTCTTTGGGACACCTGCTGC-3′; gp91phox, 5′-TGGGATCACAGGAATTGTCA-3′ and 5′-CTTCCAAACTCTCCGCAGTC-3′; p47phox, 5′-GTCCCTGCATCCTATCTGGA-3′ and 5′-GGGACATCTCGTCCTCTTCA-3′; TNF-α (5′-CGAGTGACAAGCCTGTAGCC-3′ and 5′-GGTGAGGAGCACGATGTCG-3′); IL-1 (5′ TGACGGACCCCAAAAGAHT-3′ and 5′-TCCACAGCCAACAATGAGT-3′); IL-6 (5′-TTCCATCCAGTTGCCTTCT-3′ and 5′-TCCTCTGTGAAGTCTCCTCTC-3′); and β-actin (5′-AAGGCGACAGCAGTTGG-3′ and 5′-CTGGGCCATTCAGAAATT-3′). The reaction was performed on a Roche LightCycler® 96 fluorescent quantitative PCR apparatus. QRT-PCR reaction system (20 μL): including TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RnaseH Plus) (2×) (Takara) 10 μL, cDNA 1μL, forward and reverse primers (10 μmol ·L-1) 1μL each, distilled water was added to 20 μL. Reaction procedure: 95 °C 30 s; 95 °C 5 s, 55 °C 30 s, 72 °C 10 s, a total of 40 cycles; 95 °C 15 s, 60 °C 30 s, 95 °C 1 s. There were 3 biological replicates for each gene test and 3 technical replicates for each sample.

Cell culture

The resuscitation BV2 microglia were derived from China Center for Type Culture Collection. The cells were cultured in RPM-1640 complete medium (containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin) and placed in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 saturated humidity. The liquid was changed every day, and the cells were subcultured on the next day for subsequent experiments. BV2 cells in good condition during the logarithmic growth phase were inoculated into 96-well plates and then placed in an incubator with saturated humidity of 5% CO2 at 37 °C for further culture for 12 h. BV2 cells were stimulated with LPS for 12 h, and the final concentration of LPS was 100 ng/mL. The experimental groups were normal control group, LPS model group (100 ng/mL), Cylic(PIYAG) low-dose group (Cylic(PIYAG) L + LPS, 0.01 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS), PZH medium-dose group (Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS, 0.05 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS), and PZH high-dose group (Cylic(PIYAG) H + LPS 0.20 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS).

Western blotting

The cell seed plate and administration were the same as above, then the supernatant was discarded, washed with precooled PBS 3 times, and cell lysate was added to extract the total protein. The protein concentration was measured by the BCA method, then a 5% sample buffer was added and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min for preparation of protein sample. 40 μg protein samples were taken from each group. The proteins were isolated with sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE), transferred to PVDF membrane, and then placed in skimmed milk powder (or BSA) for 1.5 h. Then incubated with a resistance (COX-2, iNOS, β-actin) and the corresponding two resistance, then the gel was developed with an imaging system. Finally, the image analysis was performed by Lab software Image.

Peptide quantitative analysis

Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) column was used with mobile phase acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid water (B). Gradient elution (0 ~ 0.1 min, 0 ~ 5% A; 0.1 ~ 1 min, 5 ~ 20% A; 1 ~ 2.5 min, 20 ~ 25% A; 2.5–7 min, 25–35% A; 7 ~ 10 min, 35% ~ 100% A; 10 ~ 10.1 min, 100% ~ 5% A; The flow rate was 0.3 mL·min-1, the injection volume was 3 μL, and the column temperature was 40 °C. The CYLIC(PIYAG) was quantitatively analyzed by AB SCIX 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Electrospray ion source (ESI), spray voltage 600 V, bunch voltage from 5 to 135 V and atomization temperature 580 °C, gas curtain 35 psi, gas atomization gas 60 psi; 60 psi auxiliary gas. The positive ion mode was used, and the scanning mode was multi-reaction monitoring (MRM). The ion pair and collision energy for quantitative analysis were at (m/z 1023.19, 30 V), respectively.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cylic(PIYAG) was labelled by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) by a commercial company (Chinapeptide, Jiangsu, China). BV2 cells were cultured in a 35 mm well (Corning, USA) for 24 h. The cell nucleus was stained with 4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI, 5 μg/mL in the medium) for 30 min. Then the well was washed by PBS for 4 times, 3 min of each. Cells were observed under the Axio Imager M2 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) after the FITC-Cylic(PIYAG) was added into the well for 30 min. Excitation wavelength of DAPI was set to 405 nm, excitation wavelength of FITC-Cylic(PIYAG) was 490 nm. 200× and 800× magnification was used to observe thesingle cell from the local-field of microscope.

Data analysis

The software SPSS 26.0 was performed one-way ANOVA on the test data, and Tukey test was used for multiple comparisons, represented by mean ± standard deviation (± s). GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used to draw a histogram, and P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussions

Effects of WPH and WPHL on the behavioral performance of mice in Morris water maze test

We used the intervention of high-dose Cylic(PIYAG) to investigate the improvement of LPS induced learning and memory impairment in mice. In the Morris water maze, the escape latency and escape distance of LPS induced mice were significantly longer than those of normal mice (shown in Supplementary Data, SF1, P < 0.05), which indicated that LPS injected mice had difficulty in locating the direction and poor memory of the target platform. The crossing times through the platform was significantly reduced (P < 0.05). However, compared with the LPS group, the spatial memory ability of mice in the Cylic(PIYAG) group was significantly enhanced, including that the escape latency was significantly shortened (P < 0.05), the residence time in the target was significantly prolonged (P < 0.05), and the crossing times though the original platform was significantly increased (P < 0.01, see Table 1). Overall, Cylic(PIYAG) owns an attribute to improve the behavioral performance of mice in the Morris water maze test.

Table 1.

Effects of Cylic(PIYAG) on the behavioristics of LPS-induced mice in Morris Maze Test

| Group | Escape distance (s) | Escape distance (mm) | Target time (s) | Crossing times | Target distance (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 382.21 ± 67.28 | 22.66 ± 6.52 | 11.93 ± 79.24 | 4.01 ± 0.64 | 211.13 ± 23.90 |

| LPS | 792.43 ± 79.24* | 49.28 ± 8.35* | 6.28 ± 0.88* | 1.27 ± 0.34* | 102.43 ± 29.06 |

| Cylic(PIYAG) + LPS | 412.35 ± 58.74 | 21.74 ± 8.96 | 12.44 ± 1.40 | 3.37 ± 0.59 | 209.78 ± 24.17 |

The data are presented as mean ± SD. The mean of escape distance was determined in total of 8 mice

*Represents P < 0.05 versus control group

Production of cytokines and proinflammatory mediators in brain influenced by Cylic(PIYAG)

The pathological characteristics of neuroinflammation were aimed at the accumulation of a large number of inflammatory cell mediators in the central nervous system and brain tissues, including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β. And mediated inflammatory immune response-related proteins, including Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and iNOS and so on, these inflammatory cytokines metabolic enzymes, long-term accumulation in the central nervous system and microenvironment will trigger the nerve inflammation cascade and accelerate the process of the central nervous system degenerative diseases (Guerreiro et al., 2007). Studies have also shown that ROS can directly damage cell membrane structure and cell membrane proteins, and induce abnormal accumulation of tau protein, thus injuring neurons (Tönnies and Trushina, 2017). Peroxide induced nerve inflammation does not exert toxic effects by the cell membrane directly, but by the superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalytic converted to hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen peroxide that can be directly through the cell membrane to activate the Nf-κB signal transduction pathway, stimulate the microglia release of TNF α, IL-6, IL-1, and NO in nerve inflammation (Wang et al., 2015). In PD model mice, inhibition of activation of microglia and release of peroxide can reduce neurotoxicity and protect neuron cells (Du et al., 2018). In the LPS-induced rat model, microglia cells in the hippocampus and forebrain stroma of the model rats can be activated, and the spatial learning ability and memory ability of the rats is decreased (Park et al., 2015; Pugh et al., 1998; Tanaka et al., 2006). Studies have also shown that LPS can activate the MAPK signaling pathway to induce the release of pro-inflammatory factors and aggravate the neuroinflammatory response (Park et al., 2015).

The levels of IL-1 and IL-6 in the brain group of mice were determined by ELISA. Compared with the control group, the expression of IL-1 and IL-6 in BV2 microglia increased significantly after 12 h of LPS stimulation, the expression of IL-1 increased from 420.0 ± 52.6 pg/mL to 682.5 ± 67.8 pg/mL (P < 0.05), and the expression of IL-6 increased from 392.1 ± 82.2 pg/mL to 667.4 ± 97.2 pg/mL (P < 0.05; Compared with the LPS model group, the expression levels of IL-1 and IL-6 were significantly decreased to 467.3 ± 37.9 pg/mL and 421.6 ± 30.1 pg/mL after 12 h of combined intervention with high-dose Cylic(PIYAG) (P < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Cylic(PIYAG) on the brain biochemical indexes of LPS-induced mice. The production of A nitrite, B MCP-1, C IL-1, D IL-6, and E TNF-α. The data are presented as mean ± SD. *Represents P < 0.05 versus LPS group

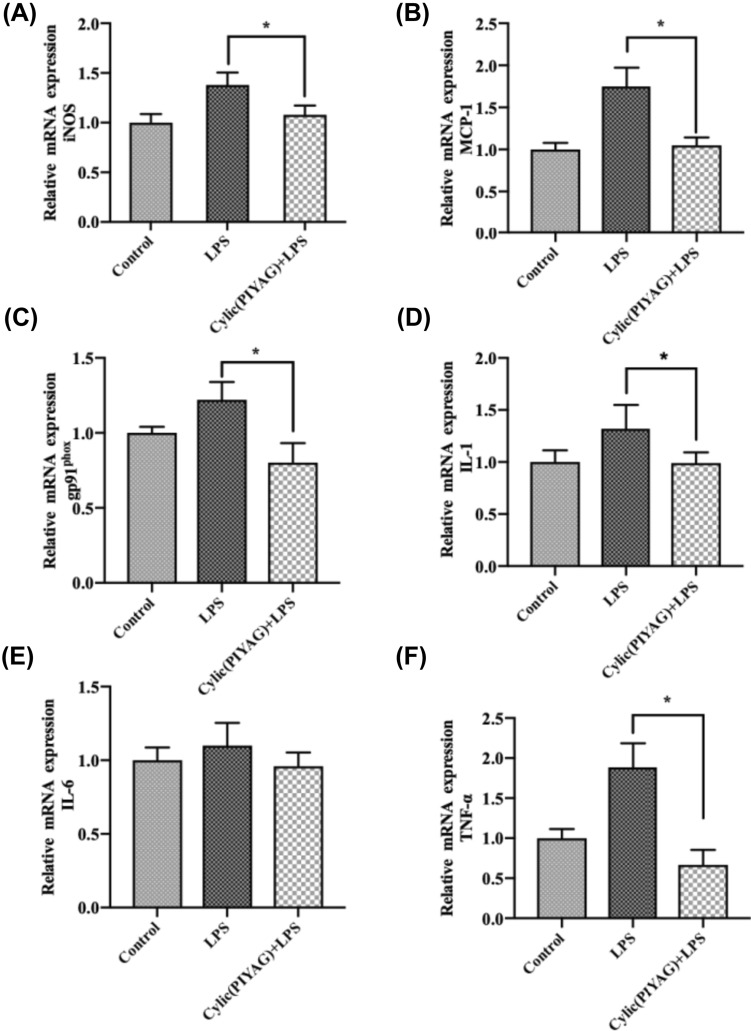

Inflammation-related gene expression in BV2 influenced by Cylic(PIYAG)

The major producers of IL-6 and TNF-α in the brain are produced by microglia (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2009; Morganti-Kossmann et al., 1999). Over-release of IL-6 and TNF-α can trigger a neuroinflammatory cascade that directly leads to brain injury and neurodegeneration (Nam et al., 2010). NO is involved in the regulation of functional homeostasis of the central nervous system (Landes et al., 2015; Salim et al., 2016). Nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and iNOS can catalyze the production of NO in the body (Landes et al., 2015). Nitric oxide catalyzed by iNOS has several hours of biological activity. The amount of NO, TNF-α, and IL-6 secreted in the early stage of inflammatory response is a marker to determine whether the inflammatory model is successfully established (Johnson et al., 2002; Morita et al., 2017). In this study, mice brain tissue was induced by LPS injection, the secretion of inflammatory mediator NO and inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 was significantly increased, which was consistent with the results of previous studies (Meneses et al., 2018), indicating that the LPS-induced inflammation model was successfully established. The gene expression of IL-1 was consistent with its level of production. Cylic(PIYAG) markedly reduced the iNOS, MCP-1, TNF-α, and gp91phox expression induced by LPS, shown in Fig. 2. Therefore, Cylic(PIYAG) decreased the expression level of inflammatory cytokines in brain tissue caused by LPS.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Cylic(PIYAG) (0.2 μM) on the mRNA expression of A–F iNOS, MCP-1, gp91phos, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α in BV-2 cells stimulated with LPS. The data are presented as mean ± SD. *Represents P < 0.05 versus LPS group

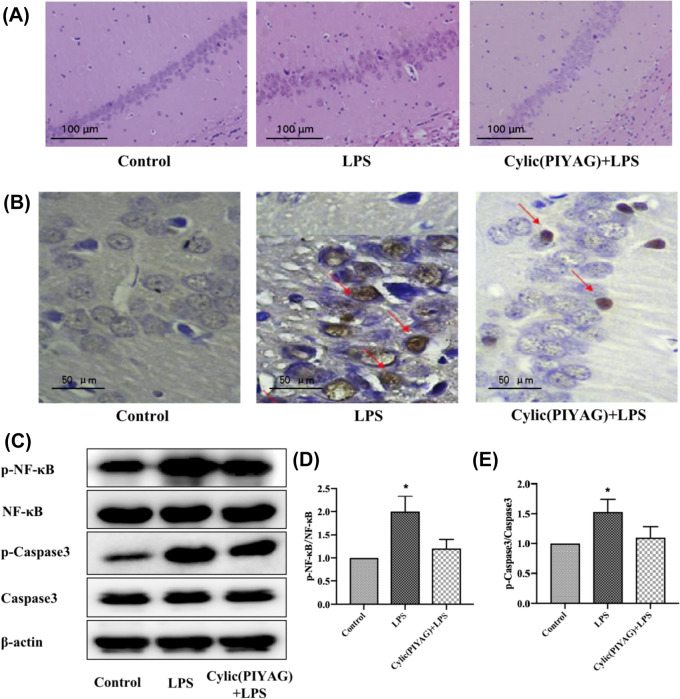

Effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on histomorphological changes of hippocampus in mice induced by LPS

The pyramidal cells in CA1 zone of control group were arranged in compact, orderly and distinct layers with regular cell shapes and clear nucleoli. In LPS-induced mice, pyramidal cells were reduced or even disappeared, with the disordered arrangement, enlarged cell space, and irregular cell shape. Compared with the model group, the number of mice pyramidal cells after Cylic(PIYAG) intervention was increased, and the cells were arranged in better order, and the cell gap was reduced, indicating that Cylic(PIYAG) had a better effect on nerve injury repair and nerve protection. The results are shown in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on changes of histomorphological region and the expression of p-NF-κB/p-Caspase3 in mice. A HE staining, observed with bar scale of 100 μm, B Immunohistochemical staining of p-caspase3, bar scale 50 μm (the dark grey plaque indicated by the red arrow is p-Caspase3); C Westerin bolting of NF-κB/Caspase3 and their Phosphorylation level of mice hippocampus; D, E The grayscale ratios of p-NF-κB /NF-κB and p-Caspase3/Caspase3 were calculated by three repeated scans and expressed as mean ± standard deviation, (P < 0.05)

Effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on histomorphological changes of hippocampus in mice induced by LPS

Immunohistochemical staining results of p-Caspase3 were shown in Fig. 4A. After the intervention of Cylic(PIYAG), the expression of p-Caspase3 in the mouse hippocampus was significantly decreased compared with that in the LPS group (The blue plaque indicated by the red arrow is p-Caspase3, Fig. 3B). The protein levels of NF-κB and Capsase3 and their phosphorylation in the brain hippocampus of mice in each group were shown in Fig. 3C, D. Compared with the Control group, the protein expressions of p-NF-κB and p-Capsase3 in the LPS group were significantly increased by 1 and 0.5 times (P < 0.05), respectively. Compared with LPS group, the protein expression levels of p-NF-κB and p-IκB-α in Cylic(PIYAG) group were significantly decreased (P < 0.05).

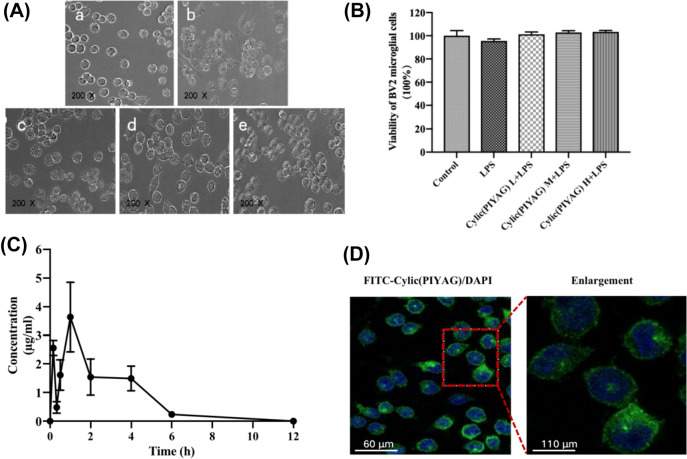

Fig. 4.

Effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on LPS-induced BV2 microglial cells. A BV2 cell growth treated with Cylic(PIYAG) for 24 h. A a, Control group; b, LPS model group, 100 ng/mL LPS; c, Cylic(PIYAG) L + LPS group, 0.01 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; d, Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.05 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; e, Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.20 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS, Microscope observation by 200×; B Viability of BV2 cell treated by low-dose of Cylic(PIYAG), medium dose of Cylic(PIYAG), high-dose of Cylic(PIYAG); C The concentration of Cylic(PIYAG) in the blood of mice after intragastric administration; D Representative images of immunofluorescence for FITC-Cylic(PIYAG). Green color for FITC-Cylic(PIYAG), blue color for DAPI; Scale left image, bar scale: 60 μm; scale the right image, bar scale: 110 μm

BV2 cell viability and internal absorption in mice

Microglia in the brain are effector cells with immune characteristics, which are easily over-activated in response to injury, infection or inflammation, and cause neuronal death and neurodegenerative diseases by releasing inflammatory mediators and ROS (Kreutzberg, 1996; Liu et al., 2020). This functional property of glial cells has also been considered beneficial to microglia-mediated neurodegeneration (Mathys et al., 2017). Therefore, therapeutic strategies that inhibit the activation of microglia may be the key to delaying the progression of senile cognitive dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases.

We hypothesized that Cylic(PIYAG) has a preventive effect on memory loss in LPS-induced cognitive decline. Hence, we investigated this possibility using LPS-injected mice, which are widely used as animal model of inflammation. Microscopic observation showed that, compared with the control group, BV2 microglia cells after 12 h LPS stimulation, the cell body became larger, the cell processes increased and became longer, indicating that the cells were activated. However, after adding different concentrations of Cylic(PIYAG), the processes of BV2 microglia cells were significantly reduced, indicating that Cylic(PIYAG) could inhibit the activation of BV2 microglia cells, as shown in Fig. 4A. In this study, the CCK8 method was used to detect the viability of BV2 cells co-cultured with LPS and Cylic(PIYAG). The results showed that LPS had slight damage to the viability of BV2, and Cylic(PIYAG) had no effect on the activity of BV2, indicating that Cylic(PIYAG) did not affect the expression of inflammatory cytokines by promoting the improvement of cell viability.

Considering that peptides are often difficult to be utilized by the body because they cannot be hydrolyzed by enzymes in the gastrointestinal environment. We also discussed the pharmacokinetics of Cylic(PIYAG) in mice. After intragastric administration of 0.1 g/(kg·d) Cylic(PIYAG) in mice, the concentration of Cylic(PIYAG) in blood reached a peak of 3.64 ± 1.22 μg/ml at 1 h by LC–MS (triple quadrupole mass spectrometry). In addition, Cylic(PIYAG) molecular signaling of MS was also detected in the CSF of Cylic(PIYAG) intragastric mice. It showed that although Cylic(PIYAG) was hydrolyzed, it could still cross the intestinal barrier and enter the blood circulation to play a role, as shown in Fig. 4C. This suggests that Cylic(PIYAG) is stable enough to be given to mice by gavage. What’s more, Cylic(PIYAG) can be localized in the cytoplasm through the membrane of BV2. As shown in Fig. 4D, Cylic(PIYAG) labeled with FITC showed green fluorescence under the microscope in vitro, indicating that Cylic(PIYAG) mainly played an anti-inflammatory role in the cytoplasm of microglia.

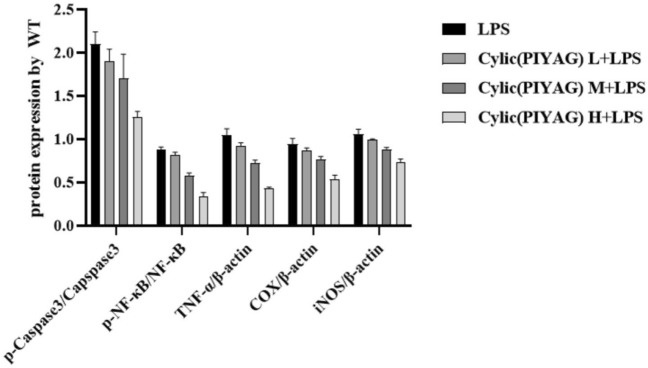

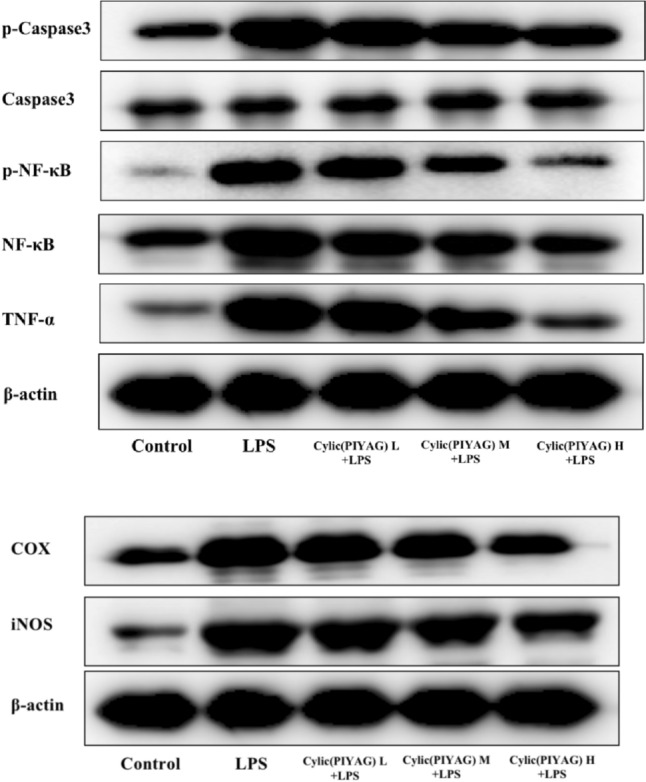

Inflammation-related proteins expression by Cylic(PIYAG)

To investigate the protective effects of Cylic(PIYAG) and on mice, we administered Cylic(PIYAG) daily to LPS-induced mice and assessed their cognitive function. The protein expression levels of COX-2 and iNOS in the cytoplasm of BV2 microglia were detected by Western blot, shown in Fig. 5. Compared with the control group, the protein levels of COX-2 and iNOS in BV2 microglia were significantly increased after 12 h of LPS stimulation (P < 0.001). Compared with LPS model group, Cylic(PIYAG) with different concentrations (0.01, 0.05 and 0.2 μM) for 12 h could significantly reduce the protein expression level of COX-2 (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05) and the protein expression level of iNOS (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05) in cells, as shown in Fig. 6. What’s more, the result of p-NF-κB, p-Caspase3, TNF-α expression was consistent with that of mouse hippocampus, which also suggested that Cylic(PIYAG) could alleviate the inflammatory response of BV2 cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on the inflammation-related proteins expression in LPS-induced BV2. Control group; LPS model group, 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) L + LPS group, 0.01 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.05 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.20 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS

Fig. 6.

The quantitative analysis inflammation-related proteins expression in LPS-induced BV2. Control group; LPS model group, 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) L + LPS group, 0.01 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.05 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS; Cylic(PIYAG) M + LPS group, 0.20 μM Cylic(PIYAG) + 100 ng/mL LPS

In addition, under inflammatory conditions, the inhibitory protein α (IκB-α) of NF-κB is activated and degraded, resulting in the separation of NF-κB. Phosphorylated activated NF-κB enters the nucleus and promotes the increase of IL-1β and TNF-α levels, leading to chronic inflammation. The results of this study showed that Cylic(PIYAG) inhibited the phosphorylation and expression of NF-κB and Caspse3 proteins, suggesting that Cylic(PIYAG) may have a protective effect on brain neuroinflammation by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway and the release of inflammatory factors. In this study, Western Blot and immunofluorescence were used to detect key proteins in the Nox2 (gp91phox/P47phox) signaling pathway (Tannich et al., 2020; Ushio-Fukai, 2006). Our results showed that LPS activated the Nox2 (gp91phox/P47phox) signaling pathway in BV-2 cells, increased the production of ROS, and finally induced the protein expression of COX-2 and iNOS in BV-2 cells. However, Cylic(PIYAG) pre-protection inhibited the overexpression of inflammatory proteins iNOS and COX-2 by inhibiting the assembly process of Nox2 and eliminating intracellular ROS. These results revealed that Cylic(PIYAG) can alleviate LPS-induced neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in BV-2 cells, which were related to the inhibition of the Nox2 signaling pathway.

In conclusion, Cylic(PIYAG) can not only reduce the release of inflammatory mediator NO and inhibit the expression of inflammatory mediator COX-2 after LPS induction, but also promote the cognitive decline of mice, suggesting that Cylic(PIYAG) has a similar effect of neurotrophic factor to improve neuroinflammatory lesions. This study is expected to provide a new candidate for a peptide inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme for the treatment of memory loss and cognitive impairment-related diseases.

Limitation and advice

Finally, there are still limitations in this study. In order to evaluate the direct effect of Cylic(PIYAG) on neuroinflammation in vivo, only wild-type mice were used. The experimental results may also be biased due to the hypotensive effect of Cylic (PIYAG). Although CylicC(PIYAG) used in normal mice without abnormal cerebral renin-angiotensin system, which avoids the excess reactive oxygen species caused by elevated Ang II, Cylic(PIYAG) may also bias the results because of its hypotensive effect effects. Besides, as the future advice, the long-term efficacy and risk of Cylic(PIYAG) should be further investigated due to its hypotensive effect.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the financial support of The Research Fund of Anhui Medical University (A20210020012).

Author contributions

Con-ceptualization, BL, XW and XS; methodology, BL; software, XW, BL; validation, XW, BL; formal analysis, XW, XS; investigation, BL; resources, BL; data curation, BL; writing-original draft preparation, EC; writing-review and editing, EC; visualization, EC; supervision, EC; project administration, EC; funding acquisition, EC All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xueying Shi, Email: aqslsxy@sina.com.

Erhua Chen, Email: erhuachen01@163.com.

References

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: A critical role for the immune system. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:670. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron J, Domenger D, Dhulster P, Ravallec R, Cudennec B. Protein digestion-derived peptides and the peripheral regulation of food intake. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2017;8:85. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Lo YC, Hu WT, Wu MC, Ten CS, Chang HM. Microencapsulation and modification of synthetic peptides of food proteins reduces the blood pressure of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51:1671–1675. doi: 10.1021/jf020900u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang PH, Hsieh PW, Yang YL, Hua KF, Chang FR, Shiea J, Wu SH, Wu YC. Cyclopeptides with anti-inflammatory activity from seeds of Annona montana. Journal of Natural Products. 2008;71:1365–1370. doi: 10.1021/np8001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Han JH, Lee SB, Lee YH. Inhalation toxicity of bisphenol A and its effect on estrous cycle, spatial learning, and memory in rats upon whole-body exposure. Toxicological Research. 2017;33:165–171. doi: 10.5487/TR.2017.33.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Da Costa J, Zhang L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y, Zhou T, Hao L, Cao J, Sun Y, Pan D. In vitro and in vivo studies on the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity peptides isolated from broccoli protein hydrolysate. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2019;67:6757–6764. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du RH, Bin SH, Hu ZL, Lu M, Ding JH, Hu G. Kir 6.1/K-ATP channel modulates microglia phenotypes: Implication in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death and Disease. 2018;9:404. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in cerebrovascular disease. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2002;2:1484–1490. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2002.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CE, Miners JS, Piva G, Willis CL, Heard DM, Kidd EJ, Good MA, Kehoe PG. ACE2 activation protects against cognitive decline and reduces amyloid pathology in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2020;139:485–502. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02098-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro RJ, Santana I, Brás JM, Santiago B, Paiva A, Oliveira C. Peripheral inflammatory cytokines as biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2007;4:406–412. doi: 10.1159/000107700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki A, Mogi M, Iwanami J, Min LJ, Bai HY, Shan BS, Kan-no H, Ikeda S, Higaki J, Horiuchi M. Recognition of early stage thigmotaxis in morris water maze test with convolutional neural network. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Zhao Q, Peng J, Yu Y, Wang C, Zou Y, Su Y, Zhu L, Wang C, Yang Y. Peptide-Polyphenol (KLVFF/EGCG) binary modulators for inhibiting aggregation and neurotoxicity of amyloid-β peptide. ACS Omega. 2019;4:4233–4242. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, O’Connor KA, Deak T, Stark M, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Prior stressor exposure sensitizes LPS-induced cytokine production. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2002;16:461–476. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: A sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends in Neurosciences. 1996;19:312–318. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes MB, Rajaram MVS, Nguyen H, Schlesinger LS. Role for NOD2 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis -induced iNOS expression and NO production in human macrophages. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2015;97:1111–1119. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A1114-557R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley T, Schott JM, Weston P, Murray CE, Wellington H, Keshavan A, Foti SC, Foiani M, Toombs J, Rohrer JD, Heslegrave A, Zetterberg H. Molecular biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and prospects. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2018;11:dmm031781. doi: 10.1242/dmm.031781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Gomes SM, Ghalayini J, Iliadi KG, Boulianne GL. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers rescue memory defects in drosophila-expressing Alzheimer’s disease-related transgenes independently of the canonical renin angiotensin system. eNeuro. 2020;7:1–18. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0235-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LR, Liu JC, Bao JS, Bai QQ, Wang GQ. Interaction of microglia and astrocytes in the neurovascular unit. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020;11:1024. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann AP, Scodeller P, Hussain S, Braun GB, Mölder T, Toome K, Ambasudhan R, Teesalu T, Lipton SA, Ruoslahti E. Identification of a peptide recognizing cerebrovascular changes in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Communications. 2017;8:1403. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathys H, Adaikkan C, Gao F, Young JZ, Manet E, Hemberg M, De Jager PL, Ransohoff RM, Regev A, Tsai LH. Temporal tracking of microglia activation in neurodegeneration at single-cell resolution. Cell Reports. 2017;21:366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses G, Rosetti M, Espinosa A, Florentino A, Bautista M, Díaz G, Olvera G, Bárcena B, Fleury A, Adalid-Peralta L, Lamoyi E, Fragoso G, Sciutto E. Recovery from an acute systemic and central LPS-inflammation challenge is affected by mouse sex and genetic background. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0201375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganti-Kossmann MC, Hans VHJ, Lenzlinger PM, Dubs R, Ludwig E, Trentz O, Kossmann T. TGF-β is elevated in the CSF of patients with severe traumatic brain injuries and parallels blood-brain barrier function. Journal of Neurotrauma. 1999;16:617–628. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita W, Dakin SG, Snelling SJB, Carr AJ. Cytokines in tendon disease: A systematic review. Bone and Joint Research. 2017;6:656–664. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.612.BJR-2017-0112.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam KN, Park YM, Jung HJ, Lee JY, Min BD, Park SU, Jung WS, Cho KH, Park JH, Kang I, Hong JW, Lee EH. Anti-inflammatory effects of crocin and crocetin in rat brain microglial cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;648:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J, Wu Z, Stoka V, Meng J, Hayashi Y, Peters C, Qing H, Turk V, Nakanishi H. Increased expression and altered subcellular distribution of cathepsin B in microglia induce cognitive impairment through oxidative stress and inflammatory response in mice. Aging Cell. 2019;18:e12856. doi: 10.1111/acel.12856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui T, Tomita N, Sato-Nakagawa T, Matsui T, Maruyama M, Niwa K, Arai H, Sasaki H. Effects of brain-penetrating ACE inhibitors on Alzheimer disease progression. Neurology. 2004;63:1324–1325. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000140705.23869.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Min JS, Kim B, Bin CU, Yun JW, Choi MS, Kong IK, Chang KT, Lee DS. Mitochondrial ROS govern the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory response in microglia cells by regulating MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Neuroscience Letters. 2015;584:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh CR, Kumagawa K, Fleshner M, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. Selective effects of peripheral lipopolysaccharide administration on contextual and auditory-cue fear conditioning. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1998;12:212–229. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WWQ, Lai A, Mon T, Mwamburi M, Taylor W, Rosenzweig J, Kowall N, Stern R, Zhu H, Steffens DC. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and Alzheimer disease in the presence of the apolipoprotein e4 allele. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;22:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quitterer U, AbdAlla S. Improvements of symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease by inhibition of the angiotensin system. Pharmacological Research. 2020;154:104230. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim T, Sershen CL, May EE. Investigating the role of TNF-α and IFN-γ activation on the dynamics of iNOS gene expression in lps stimulated macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram GM, Bramhachari PV. Molecular interplay of pro-inflammatory transcription factors and non-coding RNAs in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor Biology. 2017;39:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1010428317705760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Ide M, Shibutani T, Ohtaki H, Numazawa S, Shioda S, Yoshida T. Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation induces learning and memory deficits without neuronal cell death in rats. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2006;83:557–566. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannich F, Tlili A, Pintard C, Chniguir A, Eto B, Dang PMC, Souilem O, El-Benna J. Activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase/NOX2 and myeloperoxidase in the mouse brain during pilocarpine-induced temporal lobe epilepsy and inhibition by ketamine. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R, Wu B, Fu C, Guo K. miR-137 prevents inflammatory response, oxidative stress, neuronal injury and cognitive impairment via blockade of Src-mediated MAPK signaling pathway in ischemic stroke. Aging. 2020;12:10873–10895. doi: 10.18632/aging.103301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies E, Trushina E. Oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;57:1105–1121. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torika N, Asraf K, Apte RN, Fleisher-Berkovich S. Candesartan ameliorates brain inflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2018;24:231–242. doi: 10.1111/cns.12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucsek Z, Noa Valcarcel-Ares M, Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Fülöp G, Gautam T, Orock A, Csiszar A, Deak F, Ungvari Z. Hypertension-induced synapse loss and impairment in synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus mimics the aging phenotype: implications for the pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment. GeroScience. 2017;39:385–406. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9981-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushio-Fukai M. Redox signaling in angiogenesis: Role of NADPH oxidase. Cardiovascular Research. 2006;71:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakita S, Izumi Y, Matsuo T, Kume T, Takada-Takatori Y, Sawada H, Akaike A. Reconstruction and quantitative evaluation of dopaminergic innervation of striatal neurons in dissociated primary cultures. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;192:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Jing H, Yang H, Liu Z, Guo H, Chai L, Hu L. Tanshinone i selectively suppresses pro-inflammatory genes expression in activated microglia and prevents nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;164:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Wu M, Xu L, Xie H, Wei X. Anti-inflammatory cyclopeptides from exocarps of sugar-apples. Food Chemistry. 2014;152:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Hua KF, Chuang PH, Wu SH, Wu KY, Chang FR, Wu YC. New cyclic peptides from the seeds of Annona squamosa L. and their anti-inflammatory activities. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56:386–392. doi: 10.1021/jf072594w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.