Abstract

Trichoblastic carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal tumor with a risk of local invasion and distant metastasis. As of today, there is no consensus for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic trichoblastic carcinoma. “AcSé Nivolumab” is a multi-center Phase II basket clinical trial (NCT03012581) evaluating the safety and efficacy of nivolumab in several cohorts of rare, advanced cancers. Here we report the results of nivolumab in patients with trichoblastic carcinoma. Of the eleven patients enrolled in the study, five patients had been previously treated by sonic hedgehog inhibitors. The primary endpoint 12-week objective response rate was 9.1% (N = 1/11) with 1 partial response. Six patients who progressed under previous lines of treatment showed stable disease at 12 weeks, reflecting a good control of the disease with nivolumab. Furthermore, 54.5% of the patients (N = 6/11) had their disease under control at 6 months. The 1-year overall survival was 80%, and the median progression-free survival was 8.4 months (95%CI, 5.7 to NA). With 2 responders (2 complete responses), the best response rate to nivolumab at any time was 18.2% (95%CI, 2.3–51.8%). No new safety signals were identified, and adverse events observed herein were previously described and well known with nivolumab monotherapy. These results are promising, suggesting that nivolumab might be an option for patients with advanced trichoblastic carcinomas. Further studies on larger cohorts are necessary to confirm these results and define the role of nivolumab in the treatment of trichoblastic carcinomas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-023-03449-9.

Keywords: Adnexal tumors, Trichoblastic carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Nivolumab, Anti-PD1

Introduction

Trichoblastic carcinoma (TC) is a rare malignant adnexal tumor derived from hair follicles that usually develops on a pre-existing trichoblastoma [1, 2]. The tumor often occurs on photoexposed areas such as the face [3]. However, some cases of TCs on the extremities, the torso, the face and the coccyx have been described [3–5]. They appear on middle-aged to elderly patients, usually younger than patients with basal cell carcinomas (BCC) [2, 6]. The clinical presentations are heterogeneous, sometimes suggestive such as large ulcerated tumors, other times similar to a BCC (flesh-colored papule or nodule); thus, diagnosis is made on histological examination [7]. However, TC can be difficult to diagnose and to differentiate from a BCC, and a trained pathologist should confirm diagnosis [3, 8].

Unlike BCC, TC is an aggressive tumor with a risk of local invasion and distant metastasis [9]. For a local primary tumor, the conventional treatment is surgery [3], with a 10-mm-wide resection. Dedicated surgical approaches have been recently developed such as Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows smaller resections with a lower risk of recurrence [10]. A recent retrospective study reviewed 93 cases of TCs. The treatments used varied but remained mostly based on surgery in 82.8% of the cases [3]. For advanced and metastatic TC, there is no consensus on the treatment due to the infrequency [1, 11–13].

However, much progress has been made in recent years concerning the treatment of TC. In case of a non-operable or metastatic tumor, some authors use radiotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy [2, 14]. Some case reports documented tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib and sonic hedgehog inhibitors (SHHi) to be effective in the treatment of non-operable TCs [9, 15, 16].

SHHi, whose suggested efficiency is based on the overexpression of SHH pathway in cutaneous adnexal tumors [16, 17], may be considered as a first line treatment option in metastatic or locally advanced TCs [18]. However, there are no prospective studies evaluating these treatments in larger cohorts of patients [3, 9, 15, 16].

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression has recently been assessed among adnexal carcinomas. Duverger and al described PD-L1 expression by tumor and immune cells in TCs and other adnexal carcinomas. In this study, PD-L1 expression was detected in immune cells of 80% of TCs (N = 4/5), but none of them expressed PD-L1 in tumor cells. Moreover, PD-L1 expression has been suggested to be predictive of anti-PD-L1 treatment efficacy indicating that PD-L1 immunotherapy may be an effective treatment for TCs [19].

The AcSé Nivolumab study (NCT03012581) is a basket phase II trial, evaluating the efficacy and safety of nivolumab in rare cancers refractory to treatment without any available option. Two cohorts of rare skin cancers were considered: advanced or metastatic BCCs and adnexal carcinomas, including TCs.

Materials and methods

Patient eligibility

Patients age 18 years and older with histologically confirmed diagnosis of TC documented with metastatic or unresectable locally advanced disease, resistant or refractory to conventional therapies including chemotherapy, SHHi and/or radiotherapy, or without conventional therapeutic option was eligible provided they had a treatment-free interval of at least 21 days following previous systemic anti-cancer treatment. Patients should have adequate hematologic, renal and hepatic function, and an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1.

Patients with prior treatment with anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1, concomitant steroid medication at a dose greater than prednisone 10 mg/day or equivalent, or any contraindication to nivolumab (active autoimmune disease that has required systemic treatment in the past 2 years, history of non-infectious pneumonitis that required steroids or current pneumonitis, history of severe hypersensitivity reaction to any monoclonal antibody therapy, etc.) were not eligible. Patients with symptomatic central nervous system metastases, other malignancies within the past 5 years other than BCC or carcinoma in situ of the cervix, or pregnancy or breastfeeding were also excluded from the study.

All enrolled patients had a centralized histological proofreading to confirm TC diagnosis. Each patient was presented in a national multidisciplinary meeting CARADERM [20] during which treatment indication was validated.

Study design

AcSé Nivolumab is a French, phase II, basket, multicenter, open-label clinical trial (NCT03012581). From July 2017 to December 2020, 53 patients from 21 centers were enrolled in the rare skin cohort (Supplementary Table 1). Among this cohort, we focus here in the subset of patients with TC. All included patients were scheduled to receive 240 mg of nivolumab as a 60-min intravenous infusion on Day 1 of every 14-day cycle. Treatment had to be continued for a maximum of 24 months (or 52 cycles) or until disease progression. Treatment may have been discontinued at the initiative of either the patient or the investigator for any reason that would be beneficial to the patient, including unacceptable toxicity, inter-current conditions that preclude continuation of treatment, or patient request. Each patient received written information about the study and signed written consent. The trial was sponsored by Unicancer and conducted in compliance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Efficacy guideline E6—Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) and applicable regulatory requirements. The initial protocol was reviewed and approved by the French ethics committee (Comité de protection des personnes, CPP Ouest II, Angers) on February 16, 2017.

Study objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate the response to nivolumab in patients with TCs resistant or refractory to conventional therapies and for which no other treatment options were available.

Endpoints

Efficacy was assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1).

The primary end point was the objective response rate (ORR), defined as the percentage of patients with TCs that obtained a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), measured at the first scheduled disease assessment following study treatment initiation (day 84, ± 7 days).

The secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from inclusion until documented disease progression (PD) according to RECIST v1.1, or death, whichever occurs first; overall survival (OS), defined as the time from inclusion until death due to any cause; best response to treatment according to RECIST V1.1, measured at any disease assessment during the course of the study; response duration defined as the time from first observation of objective response (PR or CR) according to RECIST V1.1 until PD or death, whichever occurs first; and time to response, defined as the time from inclusion until observation of objective response (PR or CR) according to RECIST v1.1.

Frequency and severity of adverse events were assessed according to the NCI CTCAE v4.

Statistical methods

Primary outcome

Statistical analysis was performed on an intent-to-treat (ITT) basis whether the treatment was administered or not. Patients who prematurely withdrew from the study or where non-evaluable were considered as “nonresponders” in the analysis.

Each of the secondary evaluation criteria was reported with a confidence interval of 95%. Analysis was performed on R 4.1.1 (https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Patient’s baseline characteristics

A total of 11 patients were enrolled with TCs in 8 sites in France. The mean age was 60 years old (range 49.5–74.5). A majority of the patients were men (7 men and 4 women) and in a good physical condition, 5/11 patients were ECOG 0 (Table 1). Four patients had a locally advanced disease and seven were at a metastatic stage. Eight patients had been previously treated with a median number of 2.5 (IQR, 2 to 3) lines of treatment. The mean was of 2.75 (range 1–5). Among the previous therapeutic lines, 5 patients received chemotherapy (62.5%), 6 radiotherapy (75%) and 5 vismodegib (62.5%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Parameters | N | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11 | 60 [49.5;74.5] | |

| Gender | Male | 7 | 63.6% |

| Female | 4 | 36.4% | |

| Previous lines of treatment | 8 | 72.7% | |

| Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 2 | 25% |

| Paclitaxel | 1 | 12,5% | |

| 5-FU | 1 | 12,5% | |

| Vinorelbin | 1 | 12,5% | |

| Other | 4 | 50% | |

| Radiotherapy | 6 | 75% | |

| SHHi | Vismodegib | 5 | 62,5% |

| Lynch syndrome | 1 | 9.1% | |

| PS (ECOG) | 0 | 5 | 45.4% |

| 1 | 6 | 54.6% | |

| Metastatic disease | 7 | 63.6% | |

SHHi: sonic hedgehog inhibitors; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracile; PS: performance status

Treatment exposure

Following enrollment in the study, 10 out of the 11 patients received the treatment and 1 patient withdrew his consent before the first infusion. The median duration of treatment with nivolumab was 6.4 months (IQR, 3.0 to 22.5), for a median number of 19 cycles (range 3–52).

Efficacy

Primary outcome

At 12 weeks (W12), 1 patient (9.1%) achieved a PR, 6 (54.5%) a SD, 3 (27.3%) a PD, and no CR was reported at time point. According to the statistical analysis plan, the patient who withdrew consent and did not receive treatment was considered non-responder for ITT assessment. The ORR was 9.1% (N = 1/11) (95% CI, 0.2% to 41.3%), and disease control rate was 63.6% (95% CI, 30.8–89.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response observed at 12 weeks

| Parameters | Values | N = 11 | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed response at W12 | PD | 3 | 27.3% |

| PR | 1 | 9.1% | |

| SD | 6 | 54.5% | |

| NA | 1 |

PD progressive disease, PR partial response, SD stable disease, NA not available

The patient with a history of Lynch syndrome was evaluated at W12 as SD, but, progressed during the study.

Secondary outcomes

At 6 months, the disease was under control for 6 patients (5 SD and 1 PR) with a disease control rate of 54.5%.

The best overall response rate to nivolumab at any time was 18.2% (95%CI, 2.3–51.8%) with 2 CR (time to response: 17.5 and 27.9 months).

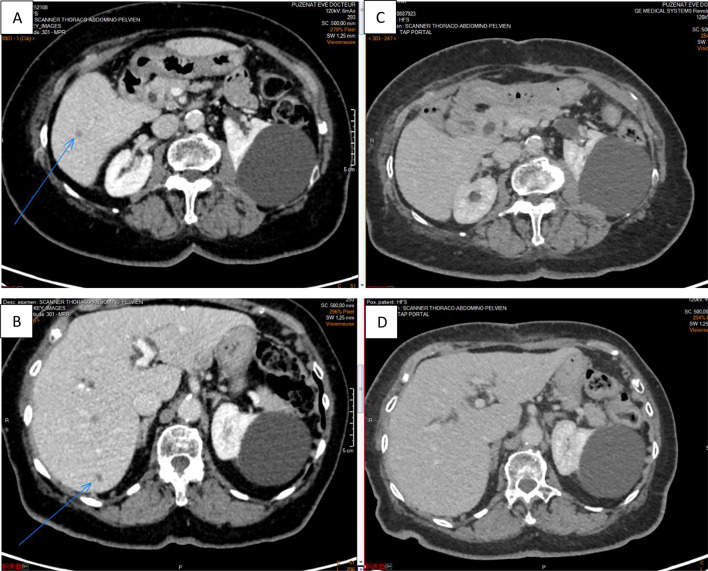

The patient who achieved a PR at W12 was naïve of systemic treatment before inclusion in the study. Figure 1 shows a complete regression of liver metastasis from November 2018 to November 2020. This patient is still in complete response to treatment one year after the last infusion of nivolumab.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT in November 2018 (A, B) and in November 2020 (C, D) showing a complete regression of liver metastasis

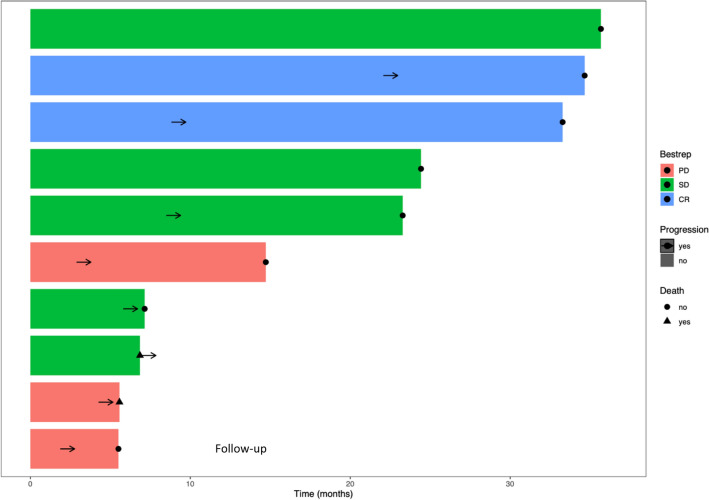

Figure 2 illustrates the follow-up of patients during the study, indicating the best response to treatment.

Fig. 2.

Swimming plot for each patient indicating the best response to nivolumab and durability of response (months)

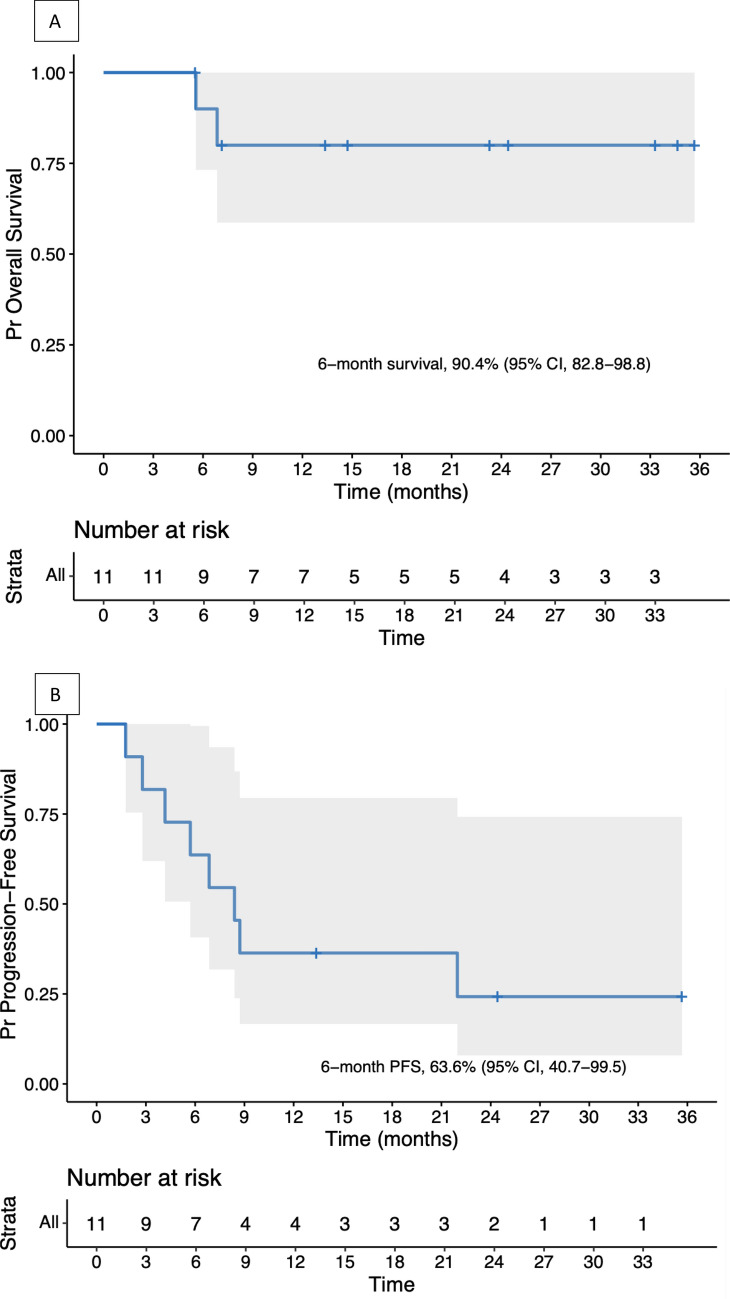

Concerning OS (Fig. 3A), the median follow-up was 14.7 months (IQR, 7–28.8). The 6-month survival rate was 90% (95% CI, 73.2–100%), and the 12-month survival rate was 80% (95% CI, 58.7–100%). One patient died of tumor progression and another one of a nivolumab-unrelated adverse event (AE).

Fig. 3.

A Overall survival and B progression-free survival of trichoblastic carcinoma patients

A total of 8 patients developed an event (disease progression or death), including 7 who progressed and 1 patient who died free of progression (due to a septic shock, unrelated to treatment).

The median PFS was 8.4 months (95%CI, 5.7 to NA) (Fig. 3B). The median duration of stable disease was 10.4 months; 2 patients had ongoing stable diseases at the end of protocol during 35.7 and 24.4 months.

Safety

Five AE grade 2 to 5 were reported for 2 patients (Table 3). The grade 5 AE reported was a septic shock not related to treatment. Among these 5 AE, 1 grade 2 hyperthyroidism and 1 grade 3 encephalopathy were considered related to treatment (40%). They were both observed on the same patient after the 3rd cycle. Only 1 AE related to treatment, the encephalopathy, resulted in the interruption of treatment. The encephalopathy resolved to a grade 1 after corticosteroid therapy but the patient died of disease progression 2 months after the interruption of treatment.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Parameters | Values | N | Related to treatment | Grade | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | |||||

| Type | Encepatholopathy | 1 | 1 | 3 | Interruption |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1 | 1 | 2 | Continuation | |

| Septic shock | 1 | 0 | 5 | Interruption | |

| Tumor bleeding | 1 | 0 | 2 | Continuation | |

| Alteration of general status | 1 | 0 | 2 | Continuation |

Therefore, 10% of the patients experienced at least 1 AE related to treatment (N = 1/10, 1 patient withdrew his consent before the beginning of treatment).

Two deaths were reported during the study, 1 due to disease progression and 1 to an AE unrelated to treatment.

Discussion

We present the results of the first phase II open-labeled, prospective, multicenter study evaluating the response to nivolumab monotherapy in a cohort of patients with a TC not eligible for surgical excision. The 12-week overall response rate was 9.1% and the 6-month disease control rate at 54.5% (N = 6/11) with a median PFS of 8.4 months. Our study shows that anti-PD1 immunotherapy may have an objective anti-tumor activity on TC. Our results are supported by a pre-existing scientific landscape with the expression of PDL1 by tumor and immune cells in TCs [19]. The overall treatment was well tolerated with a low number of AE. The better toxicity profile reported in our study compared to previous studies may be related to the small sample size. Indeed, based on the literature, 65.8% of patients experienced at least 1 AE and 16.5% developed grade 3 or worse AEs [21].

Late response to treatment was observed with 2 patients who achieved CR after the W12 analysis of the primary objective. Previous studies reported that time to response to immunotherapy can be delayed, and therefore seen after the first assessment, as described for squamous cell carcinoma and BCC with cemiplimab [22, 23]. A longer follow-up might show an increase in patient responders to nivolumab treatment.

In this study, 8 out of the 11 patients had been previously treated with chemotherapy, SHHi or radiotherapy and 62.5% (N = 5/8) had progressed during prior treatment by vismodegib. Six patients showed SD at W12 evaluation which reflects a good control of the disease, as this population of patients had progressed under previous lines of treatment. Interestingly, the 2 patients who achieved CR were naïve of treatment when they entered the study. The 3 patients evaluated as PD at time-point had all received a prior treatment varying from 1 previous line of treatment to 5. As for the 4 SD, 1 patient had not received a prior treatment; the 3 others had received between 2 and 4 different lines of treatment. This may suggest that the use of nivolumab in first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic TCs might show better results with a higher response rate and control of the disease.

The strength of our study remains on the prospective and multicenter study design as well as the number of enrolled patients for such a rare tumor.

The limits are the power of the study, the absence of a control group and standardization.

SHHi are considered first-line treatments for unresectable TCs. A recent multicenter retrospective study of 16 TC patients reported efficacy of vismodegib with an overall response rate at 62.5% (2 CR and 8 PR) and a median PFS at 7 months [18]. However, immunotherapy seems to be an interesting therapeutic option, especially in the case of contraindication or intolerance (change or loss of taste, decreased appetite, hair loss, muscle spasms) to SHHi.

Results are promising for the treatment of these rare and potentially aggressive tumors. Our study shows a preliminary signal of anti-tumoral activity of nivolumab for the treatment of TC patients and justifies further development in this highly orphaned indication.

Conclusion

Nivolumab may be an alternative for patients with TCs beyond any therapeutic resources. The results of this study are promising with a control of the disease at W12 in 63.6% of patients (6 SD and 1 PR) with a median PFS of 8.4 months and a late response to treatment with 2 CR. The tolerance of treatment was good with few side effects observed. As late and delayed responses were observed with immunotherapy, longer follow-up of included patients is promising.

Other studies are necessary to confirm these results and define the role of nivolumab in the treatment of TCs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse events

- BCC

Basal cell carcinoma

- CR

Complete response

- ITT

Intent to treat

- NA

Not available

- NCI CTCAE v4

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event version 4

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progression disease

- PD-L1

Programmed death ligand 1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PR

Partial response

- SD

Stability disease

- SHHi

Sonic hedgehog inhibitors

- TC

Trichoblastic carcinoma

Author contributions

ET collected the data and wrote the first draft of the article. SC and CC participated in the statistical analysis of the collected data and in the review of the article. MB, EMN, CN, FLD, NM, MDP, ES-B, MB-B, TJ collected the data and participated in the review of the article. MV and PJ participated in the review of the article. LG represented the collaboration with the National Cancer Institute (INCa) and participated in the review of the article. AL-G and CS were representatives of the sponsor, Unicancer, and its Immuno-Oncology Group, participated in the data transmission and in the review of the article. AM and LM initiated and supervised the study project, collected the data and participated in the final review of the article.

Funding

The trial AcSé Nivolumab was funded by the National Cancer Institute (INCa), the “Ligue Contre le Cancer” and BMS.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

AM: Over the last 5 years, AM has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards of the following companies commercializing PD-1/PD-L1 targeted immunotherapies: BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi, Merck Serono, Roche/Genentech, Astra Zeneca. Gustave Roussy has received funding for clinical trials from the following companies: BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi, Merck Serono, Roche/Genentech, Astra Zeneca. AM through Gustave Roussy has received translational research grants from BMS, Foundation MSD Avenir, Sanofi and Astra Zeneca. NM: over the last 5 years, NM has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards of BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Sun pharma. NM received grants from BMS and MSD for clinical and translational research. CN: over the last 5 years, CN has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards of BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre and Sanofi. MBB: over the last 5 years, MBB has provided time as speaker for Sun Pharma and has received grant from Roche for translational research. MDP: over the last years, MDP has provided time as speaker and investigator for BMS and MSD, and speaker for Novartis. ESB: over the last five years, ESB has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards for BMS, MSD, Merck Serono and Lilly. ESV received grants from AstraZeneca. MB: over the last 5 years, MB has provided time for scientific advisory board for BMS, time for consulting for Innate Pharma, CerbaResearch, Quantum Genomics, has provided time as a speaker for Kyowa kirin, Takeda, and has received translational research grants from Takeda and Kyowa kirin. EMN: Novartis, Pierre Favre. FLD: over the past years, FLD has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards of Daiichi, Lilly, Seagen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Myriad, has provided time as a speaker for Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, Pierre Fabre. LM: over the past years, LM has provided time for consulting and participation to scientific advisory boards of the following companies: Sun Pharma, Novartis, Pierre Fabre and MSD, and has participated in congress with the same companies. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee (NCT03012581).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Regauer S, Beham-Schmid C, Okcu M, Hartner E, Mannweiler S. Trichoblastic carcinoma (“malignant trichoblastoma”) with lymphatic and hematogenous metastases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:673–678. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JS, Kwon JH, Jung GS, Lee JW, Yang JD, Chung HY, et al. A giant trichoblastic carcinoma. Arch Craniofacial Surg. 2018;19:275–278. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boettler MA, Shahwan KT, Abidi NY, Carr DR. Trichoblastic carcinoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00403-021-02241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leblebici C, Altinel D, Serin M, Okcu O, Yazar SK. Trichoblastic carcinoma of the scalp with rippled pattern. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60:97. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.200024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Triaridis S, Papadopoulos S, Tsitlakidis D, Printza A, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Trichoblastic carcinoma of the pinna. A rare case Hippokratia. 2007;11:89–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J-T, Lee S-H, Cho P-D, Shin H-W, Kim H-S. Trichoblastic carcinoma arising from a nevus sebaceous. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43:297–299. doi: 10.5999/aps.2016.43.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia A, Nguyen JM, Stetson CL, Tarbox MB. Facial trichoblastic carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a new indication for Mohs? JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:561–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaacoub E, El Borgi J, Challita R, Sleiman Z, Ghanime G. Pinna high grade trichoblastic carcinoma, a report. Clin Pract. 2020;10:1204. doi: 10.4081/cp.2020.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battistella M, Mateus C, Lassau N, Chami L, Boukoucha M, Duvillard P, et al. Sunitinib efficacy in the treatment of metastatic skin adnexal carcinomas: report of two patients with hidradenocarcinoma and trichoblastic carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Lara L, Bonsang B, Zimmermann U, Blom A, Chapalain M, Tchakerian A, et al. Formalin-fixed tissue Mohs surgery (slow Mohs) for trichoblastic carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/jdv.18309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Trichogerminoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz T, Proske S, Hartschuh W, Kurzen H, Paul E, Wünsch PH. High-grade trichoblastic carcinoma arising in trichoblastoma: a rare adnexal neoplasm often showing metastatic spread. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:9–16. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000142240.93956.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen BD, Seetharam M, Ocal TI. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging of trichoblastic carcinoma with nodal metastasis. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44:e423. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berniolles P, Okhremchuk I, Valois A, Aymonier M, Abed S, Boyé T, et al. Carcinome trichoblastique géant : 3 observations. Ann Dermatol Vénéréologie. 2019;146:828–831. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2019.09.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepesant P, Crinquette M, Alkeraye S, Mirabel X, Dziwniel V, Cribier B, et al. Vismodegib induces significant clinical response in locally advanced trichoblastic carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1059–1062. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becquart O, Cribier B, Guillot B, Girard C. Rémission complète et prolongée d’un carcinome trichoblastique métastatique traité par vismodegib. Ann Dermatol Vénéréologie. 2015;142:S517. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2015.10.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavalieri S, Busico A, Capone I, Conca E, Dallera E, Quattrone P, et al. Identification of potentially druggable molecular alterations in skin adnexal malignancies. J Dermatol. 2019;46:507–514. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duplaine A, Beylot-Barry M, Mansard S, Arnault J-P, Grob J-J, Maillard H, et al. Vismodegib efficacy in unresectable trichoblastic carcinoma: a multicenter study of 16 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1365–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duverger L, Osio A, Cribier B, Mortier L, De Masson A, Basset-Seguin N, et al. Heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression and CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes among subtypes of cutaneous adnexal carcinomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68:951–960. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02334-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battistella M, Balme B, Jullie M-L, Zimmermann U, Carlotti A, Crinquette M, et al. Impact of expert pathology review in skin adnexal carcinoma diagnosis: analysis of 2573 patients from the French CARADERM network. Eur J Cancer. 2022;163:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magee DE, Hird AE, Klaassen Z, Sridhar SS, Nam RK, Wallis CJD, et al. Adverse event profile for immunotherapy agents compared with chemotherapy in solid organ tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migden MR, Khushalani NI, Chang ALS, Lewis KD, Schmults CD, Hernandez-Aya L, et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:294–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stratigos AJ, Sekulic A, Peris K, Bechter O, Prey S, Kaatz M, et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: an open-label, multi-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:848–857. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.