Abstract

Background

Concomitant medications may potentially affect the outcome of cancer patients. In this sub-analysis of the ARON-2 real-world study (NCT05290038), we aimed to assess the impact of concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI), statins, or metformin on outcome of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) receiving second-line pembrolizumab.

Methods

We collected data from the hospital medical records of patients with mUC treated with pembrolizumab as second-line therapy at 87 institutions from 22 countries. Patients were assessed for overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall response rate. We carried out a survival analysis by a Cox regression model.

Results

A total of 802 patients were eligible for this retrospective study; the median follow-up time was 15.3 months. PPI users compared to non-users showed inferior PFS (4.5 vs. 7.2 months, p = 0.002) and OS (8.7 vs. 14.1 months, p < 0.001). Concomitant PPI use remained a significant predictor of PFS and OS after multivariate Cox analysis. The use of statins or metformin was not associated with response or survival.

Conclusions

Our study results suggest a significant prognostic impact of concomitant PPI use in mUC patients receiving pembrolizumab in the real-world context. The mechanism of this interaction warrants further elucidation.

Keywords: Urothelial cancer, Proton pump inhibitors, Statins, Metformin, ARON-2 study, Immunotherapy

Introduction

In recent years, the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1)/ligand-1 (PD-L1) for the treatment of advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) has improved outcomes and quality of life of these patients [1, 2]. Currently, ICIs are approved in three indications for mUC: (1) first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with high PD-L1-expressing tumors or any platinum-ineligible patients regardless of PD-L1 status (atezolizumab, pembrolizumab); (2) second-line treatment following platinum-based chemotherapy or progression within 12 months after neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab), and (3) switch maintenance therapy following platinum-based chemotherapy (avelumab) [2–5].

Patients with advanced solid cancers often have other relevant comorbidities, implying a significant number of concomitant medications. Drug–drug interactions as well as potential anticancer effects of commonly used drugs have become an area of increasing interest. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins, and metformin represent the most commonly prescribed drugs worldwide including cancer patients. Recent studies have reported possible detrimental effects of concomitant medications, including antibiotics, PPIs, and corticosteroids, on the efficacy of ICIs in patients with several malignancies [6–16], including mUC [13–17]. In particular, PPIs are among the most commonly prescribed drugs for patients with cancer to reduce gastrointestinal toxicity associated with certain anticancer drugs [18]. However, the potential risk of their direct and/or indirect interactions with anticancer agents is high in terms of bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and immunological interference, the latter possibly mediated by microbiota [19, 20]. Consequently, the effectiveness of anticancer compounds may be altered by taking concomitant PPI alone or in combination with steroids and/or antibiotics [7, 16, 21]. The impact of PPI intake during ICI immunotherapy for mUC has been suggested very recently by three relatively small studies [13–17]. In contrast to PPIs, the concomitant administration of metformin or statins seems to be associated with favorable outcome in patients with advanced cancer treated with ICIs. Recent data suggest potential synergistic antitumor effects of the concomitant use of ICIs as monotherapy with the oral hypoglycemic agent metformin in patients with cancer and diabetes mellitus, possibly due to the elicitation of multiple cross-mechanisms between cancer metabolism and the host immune system in controlling cancer cell growth [22]. Nevertheless, when ICIs were used in the context of the first-line combination therapy in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, the role of concomitant metformin intake was not confirmed [23]. Additionally, concomitant statin exposure in cancer patients treated with ICIs may also lead to favorable outcomes. It has been demonstrated that statins exert a series of biological activities with high potential to enhance the effect of ICIs. Specifically, statins modulate the cancer cell metabolism and are also involved in multiple immune system functions including T-cell signaling, antigen presentation, immune cell migration and cytokine production [23–26]. To our knowledge, there are no data on a possible association between metformin or statin intake and outcome of mUC patients treated with ICIs.

The ARON project has been designed to create a global network to allow uro-oncologists to share and discuss their experiences on the use of immunotherapy and other emerging drugs in patients with genitourinary cancers. Specifically, the ARON-2 study (NCT05290038) was designed to globally collect real-world data on the use of pembrolizumab for mUC. The aim of the present analysis was to assess the association of concomitant use of PPIs, metformin, or statins with patient outcomes in the ARON-2 study population.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient population

We retrospectively analyzed data from patients with a cytologically and/or histologically confirmed mUC, treated with second-line pembrolizumab. The clinical data were collected between January 1, 2016, and October 1, 2022. We retrospectively reviewed anonymized data obtained from the hospital information systems sent by participating centers.

The study protocol "ARON-2" (No. 2022 39) was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Marche Region (Italy) on February 17, 2022, and complied with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research, the Declaration of Helsinki, and local laws in each participating center. The informed consent with subsequent analysis of the follow-up data was obtained from all the participants.

Pembrolizumab was administered intravenously as a single agent at the standard approved schedule (200 mg every 3 weeks). The treatment was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal. None of the patients had received prior ICI therapy. Concomitant PPIs, statins, and metformin were administered orally at individualized doses under the supervision the patients’ healthcare providers. Standard follow-up for patients receiving pembrolizumab generally consisted of periodic physical examinations, and laboratory analyses were usually carried out every 3–6 weeks. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) was performed at baseline and every 2–4 months thereafter, according to physicians’ practice, or when disease progression was clinically suspected.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the ARON-2 study was response, assessed by progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and overall response rate (ORR). This sub-analysis evaluates the correlation between the concomitant use of PPIs, metformin or statins, and these outcomes of mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab. PFS was defined as the time from the start of pembrolizumab to progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as the time from the start of pembrolizumab until death or lost at follow-up. We considered as censored those patients without progression or death at the last follow-up. The objective response to pembrolizumab was assessed according to RECIST 1.1 principles, and data on complete (CR) or partial responses (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) were collected and analyzed [27]. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved CR or PR per RECIST 1.1 criteria.

Statistical analysis

PFS and OS were estimated by using the Kaplan–Meier method with Rothman’s 95% confidence intervals (CI) and compared using the log-rank test. The median follow-up was calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed by using Cox proportional hazards models. The Chi-square test was used to assess potential differences between PPIs, statin or metformin users versus non-users in terms of patient characteristics and ORR. Subsequently, survival analyses focusing on the impact of PPI use in specific patient subgroups were performed. These subgroups were defined by: gender (males, females), age (< 65 years, ≥ 65 years), smoking (current and former smokers, non-smokers), histology (pure UC, other variants), ECOG-PS (0–1, ≥ 2), primary tumor site (lower urinary tract, upper urinary tract), type of metastatic spread (synchronous metastases = mUC initially diagnosed in stage IV, metachronous metastases = metastatic relapse of initially localized-stage UC), site of distant metastases (lymph node—non-regional, bone, lung, liver), pembrolizumab setting (Cohort A = mUC patients progressed after first-line chemotherapy, Cohort B = metastatic relapse within < 1 years from adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy). Significance levels were set at a 0.05 value, and all p values were two-sided. The statistical analysis was performed by using MedCalc version 19.6.4 (MedCalc Software, Broekstraat 52, 9030 Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, the study included 802 mUC patients. The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median follow-up time was 15.3 months (95% CI 14.0–76.0). In 307 (38%) patients, pembrolizumab therapy was ongoing at the time of data cut-off; 430 (54%) patients had died at the time of data cut-off; 535 (67%) patients received pembrolizumab following progression during first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (Cohort A) and 267 (33%) after disease recurrence within < 12 months since the completion of adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Cohort B). One hundred and sixty-two (32.7%) of the 495 patients with progression on pembrolizumab received further therapies (103 in cohort A and 59 in cohort B).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics in the overall study population and stratified by concomitant medications

| Patients | Overall 802 (%) |

PPI users 372 (%) | PPI non-users 430 (%) | p | Statin users 185 (%) |

Statin non-users 617 (%) | P | Metformin users 98 (%) |

Metformin non-users 704 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 591 (74) | 277 (74) | 314 (73) | 0.873 | 145 (78) | 446 (72) | 0.328 | 77 (79) | 514 (73) | 0.322 |

| Female | 211 (26) | 95 (26) | 116 (27) | 40 (22) | 171 (28) | 21 (21) | 190 (27) | |||

| Age ≥ 65 years | 595 (74) | 285 (77) | 310 (72) | 0.418 | 151 (81) | 444 (72) | 0.134 | 83 (85) | 512 (73) | 0.038 |

| ECOG-PS ≥ 2 | 138 (17) | 74 (20) | 64 (15) | 0.353 | 40 (22) | 98 (16) | 0.281 | 13 (13) | 125 (18) | 0.330 |

| Current or former smokers | 521 (65) | 253 (68) | 268 (62) | 0.375 | 130 (70) | 391 (63) | 0.296 | 63 (64) | 458 (65) | 0.883 |

| Primary tumor location | ||||||||||

| Upper urinary tract | 214 (27) | 108 (29) | 106 (25) | 0.525 | 44 (24) | 170 (28) | 0.520 | 23 (23) | 191 (27) | 0.515 |

| Lower urinary tract | 588 (73) | 264 (71) | 324 (75) | 141 (76) | 447 (72) | 75 (77) | 513 (73) | |||

| Tumor histology | ||||||||||

| Pure urothelial carcinoma | 648 (81) | 307 (83) | 341 (79) | 0.472 | 157 (85) | 491 (80) | 0.353 | 87 (89) | 561 (80) | 0.079 |

| Minor or mixed variants | 154 (19) | 65 (17) | 89 (21) | 28 (15) | 126 (20) | 11 (11) | 143 (20) | |||

| Synchronous metastatic disease | 246 (31) | 113 (30) | 133 (31) | 0.878 | 50 (27) | 196 (32) | 0.439 | 29 (30) | 217 (31) | 0.878 |

| Common sites of metastasis | ||||||||||

| Lymph nodes (non-regional) | 564 (70) | 263 (71) | 301 (70) | 0.877 | 128 (69) | 436 (71) | 0.758 | 73 (74) | 491 (70) | 0.530 |

| Lung | 265 (33) | 120 (32) | 145 (34) | 0.764 | 64 (35) | 201 (33) | 0.766 | 43 (44) | 222 (32) | 0.081 |

| Bone | 227 (28) | 114 (31) | 113 (26) | 0.435 | 52 (28) | 175 (28) | 1.000 | 33 (34) | 194 (28) | 0.360 |

| Liver | 146 (18) | 71 (19) | 75 (17) | 0.714 | 48 (26) | 98 (16) | 0.083 | 22 (22) | 124 (18) | 0.481 |

| Brain | 11 (1) | 7 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.562 | 5 (3) | 6 (1) | 0.314 | 4 (4) | 7 (1) | 0.175 |

| Pembrolizumab setting | ||||||||||

| Cohort A (progressed after first-line chemotherapy) | 535 (67) | 265 (71) | 270 (63) | 0.230 | 115 (62) | 420 (68) | 0.375 | 68 (69) | 467 (66) | 0.651 |

| Cohort B (recurred within < 1 year from adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy) | 267 (33) | 107 (29) | 160 (37) | 70 (38) | 197 (32) | 30 (31) | 237 (34) | |||

Concomitant use of PPIs, statins or metformin was reported in 372 (46%), 185 (23%) and 98 (12%) patients, respectively. The use of metformin was more frequent in patients aged ≥ 65 years, while no differences were found in baseline patient characteristics according to the concomitant use of PPIs or statins (Table 1).

Survival analysis

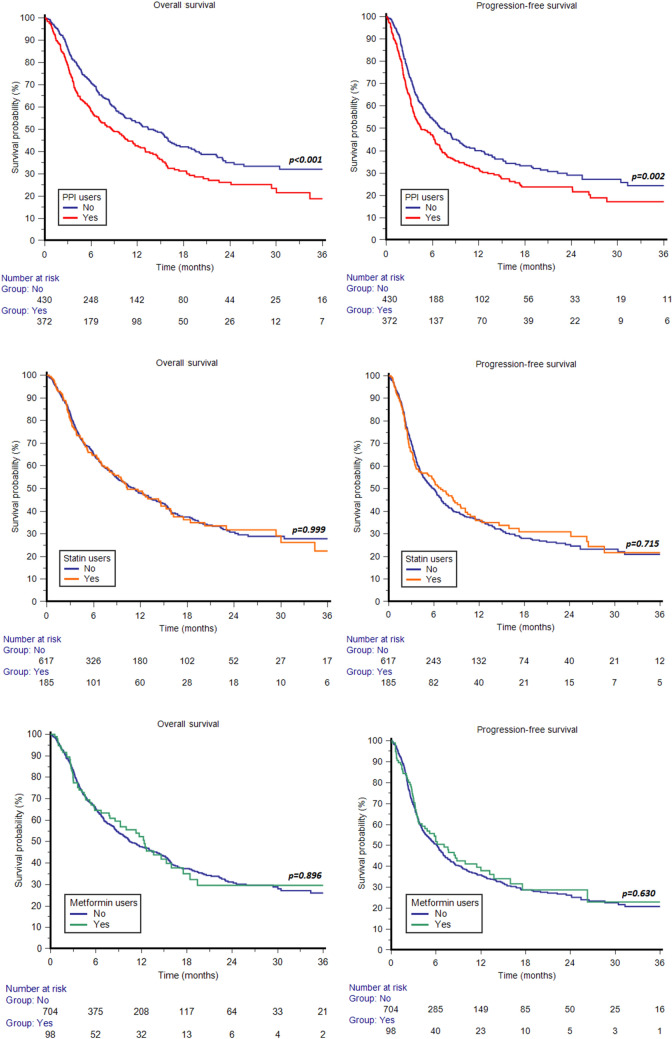

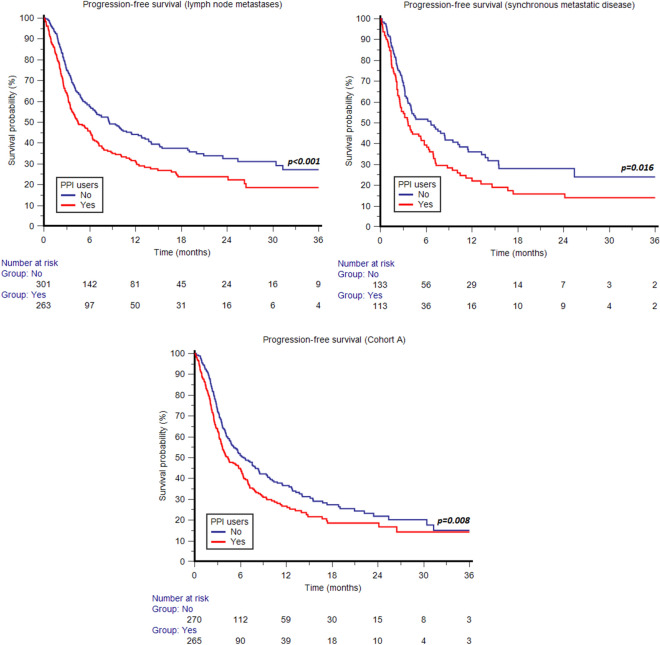

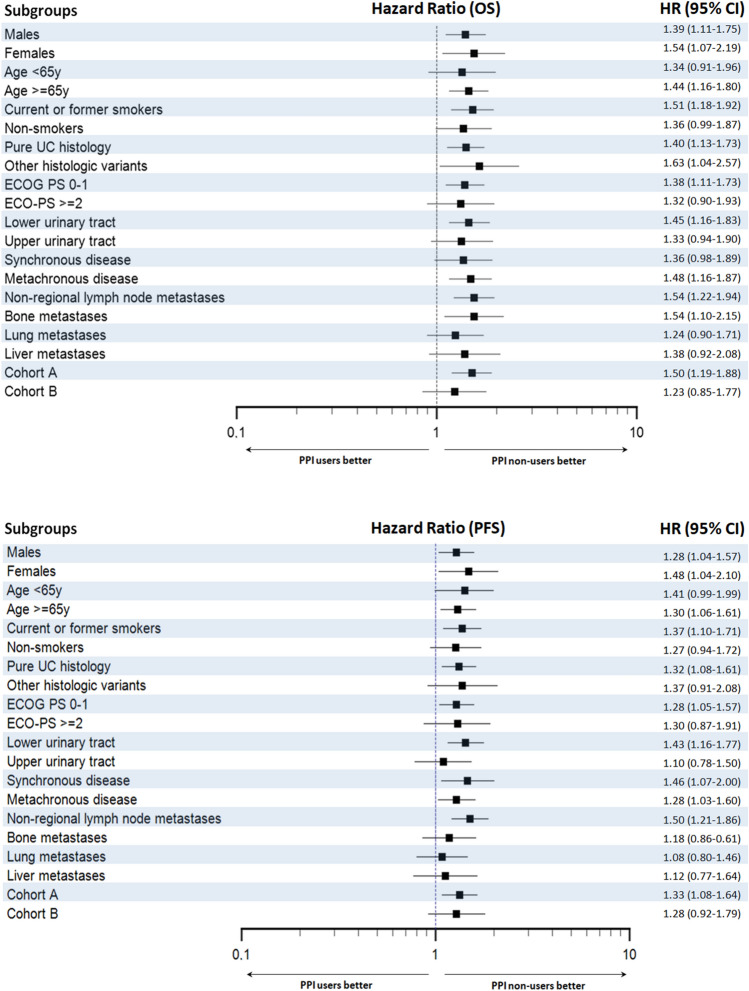

Median PFS and OS for the whole cohort were 6.2 (95% CI 5.1–6.9) and 11.3 months (95% CI 9.5–13.0), respectively. Median PFS and OS for PPI users were 4.5 (95% CI 3.7–6.3) and 8.7 (95% CI 6.9–11.4) months versus 7.2 (95% CI 5.7–9.1) and 14.1 months (95% CI 10.4–16.2) for PPI non-users (p = 0.002 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1). Median PFS and OS for statin users were 6.9 (95% CI 4.0–9.5) and 10.3 (95% CI 8.0–15.3) months versus 6.0 (95% CI 4.8–6.9) and 11.3 months (95% CI 9.1–13.4) months for statin non-users (p = 0.715 and p = 0.999, respectively) (Fig. 1). Median PFS and OS for metformin users were 7.1 (95% CI 3.7–12.0) and 12.4 (95% CI 7.8–16.0) months versus 6.2 (95% CI 5.0–6.9) and 10.5 (95% CI 9.0–13.3) months for metformin non-users (p = 0.630 and p = 0.896, respectively) (Fig. 1). Forest plots summarizing HRs and 95% CIs for OS and PFS according to the assessed comedication are displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival and progression-free survival according to the use of concomitant proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins or metformin

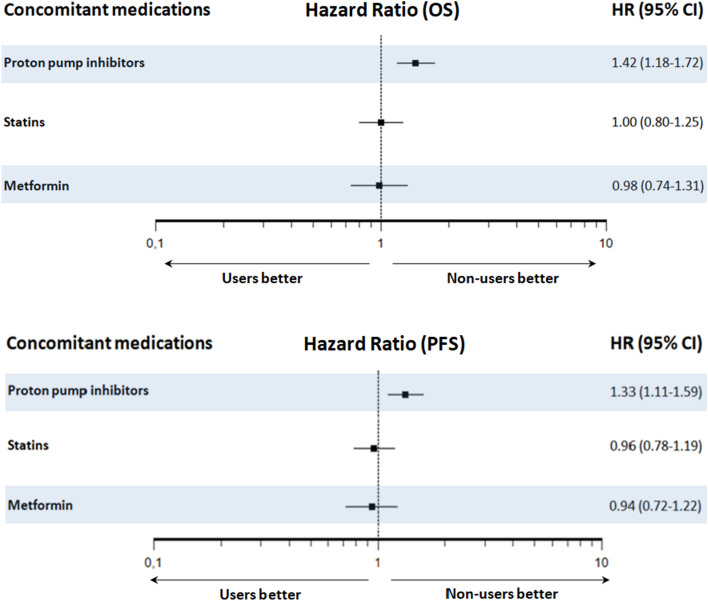

Fig. 2.

Forest plots showing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to the use of concomitant proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), statins and metformin

In the Cox multivariate analysis, the use of PPIs remains a significant and independent factor predicting both PFS (HR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.53, p = 0.006) and OS (HR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.17–1.71, p < 0.001). Other independent prognostic factors were synchronous metastatic disease, bone and liver metastases for PFS; and smoking status, synchronous metastatic disease, bone and liver metastases for OS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS)

| Overall survival | Univariate cox regression | Multivariate cox regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Gender (females vs. males) | 1.22 (0.99–1.50) | 0.062 | ||

| Age (≥ 65 years vs. < 65 years) | 1.07 (0.86–1.33) | 0.530 | ||

| Smoking (smokers vs. non-smokers) | 0.81 (0.66–0.98) | 0.030 | 0.78 (0.64–0.95) | 0.012 |

| Histology (mixed vs. pure UC) | 1.04 (0.81–1.32) | 0.775 | ||

| Upper vs. lower urinary tract | 1.10 (0.90–1.36) | 0.353 | ||

| Synchronous metastatic disease (yes vs. no) | 1.32 (1.08–1.61) | 0.007 | 1.33 (1.09–1.63) | 0.005 |

| Lymph node metastases (Y vs. N) | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 0.151 | ||

| Bone metastases (Y vs. N) | 1.53 (1.25–1.88) | < 0.001 | 1.51 (1.22–1.84) | < 0.001 |

| Liver metastases (Y vs. N) | 1.46 (1.16–1.84) | 0.001 | 1.39 (1.10–1.75) | 0.006 |

| Proton pump inhibitors (Y vs. N) | 1.41 (1.17–1.71) | < 0.001 | 1.41 (1.17–1.70) | < 0.001 |

| Statins (Y vs. N) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.999 | ||

| Metformin (Y vs. N) | 0.98 (0.73–1.31) | 0.896 | ||

| Progression-free survival | Univariate cox regression | Multivariate cox regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Gender (females vs. males) | 0.99 (0.81–1.22) | 0.957 | ||

| Age (≥ 65 years vs. < 65 years) | 0.93 (0.76–1.14) | 0.485 | ||

| Smoking (smokers vs. no-smokers) | 0.93 (0.77–1.11) | 0.409 | ||

| Histology (mixed vs. pure UC) | 1.03 (0.83–1.29) | 0.771 | ||

| Upper vs. lower urinary tract | 1.04 (0.86–1.27) | 0.681 | ||

| Synchronous metastatic disease (yes vs. no) | 1.28 (1.06–1.55) | 0.009 | 1.24 (1.02–1.49) | 0.027 |

| Lymph node metastases (Y vs. N) | 0.86 (0.71–1.04) | 0.130 | ||

| Bone metastases (Y vs. N) | 1.48 (1.22–1.79) | < 0.001 | 1.42 (1.17–1.71) | < 0.001 |

| Liver metastases (Y vs. N) | 1.51 (1.22–1.86) | < 0.001 | 1.44 (1.17–1.79) | < 0.001 |

| Proton pump inhibitors (Y vs. N) | 1.32 (1.10–1.58) | 0.002 | 1.28 (1.08–1.53) | 0.006 |

| Statins (Y vs. N) | 0.96 (0.78–1.19) | 0.716 | ||

| Metformin (Y vs. N) | 0.94 (0.71–1.23) | 0.935 | ||

ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status; UC = Urothelial Carcinoma

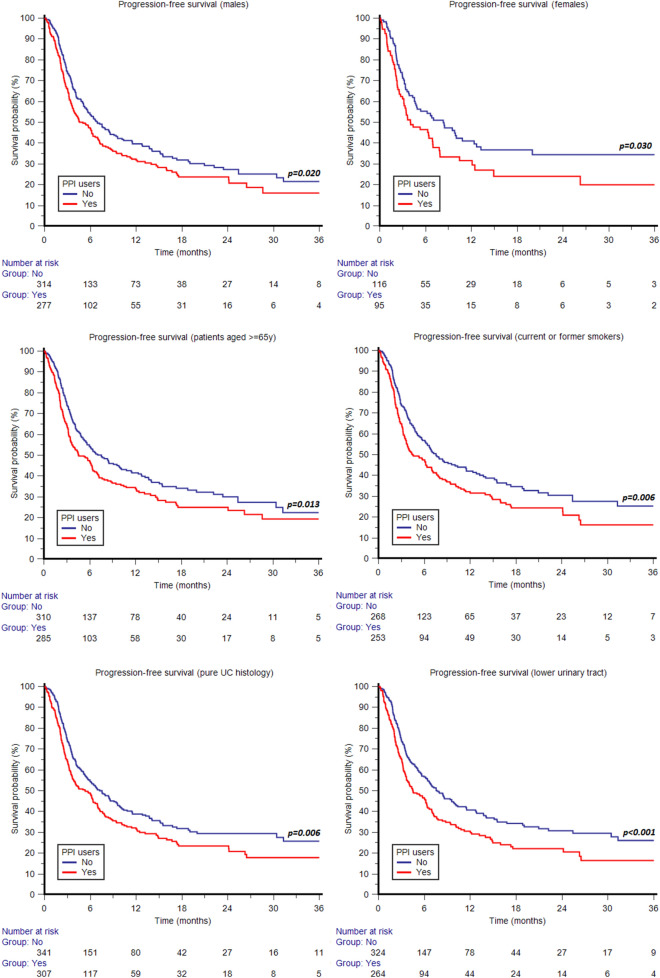

Subgroup survival analyses according to the concomitant use of PPIs

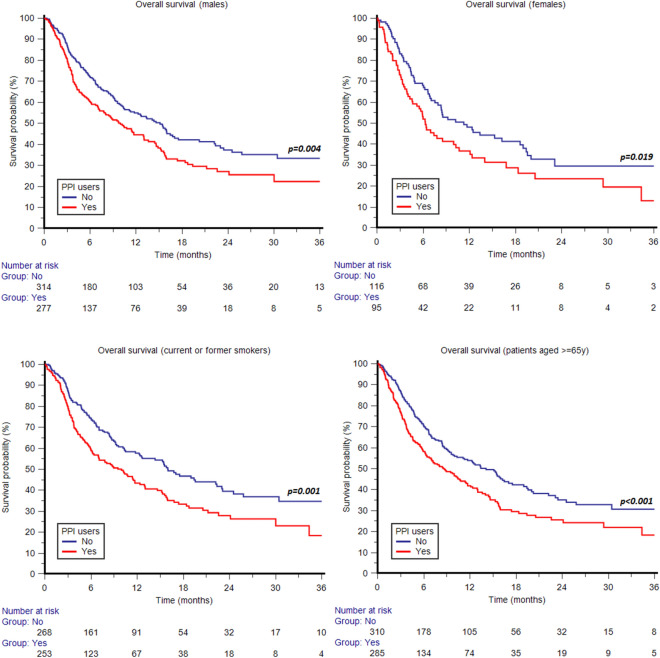

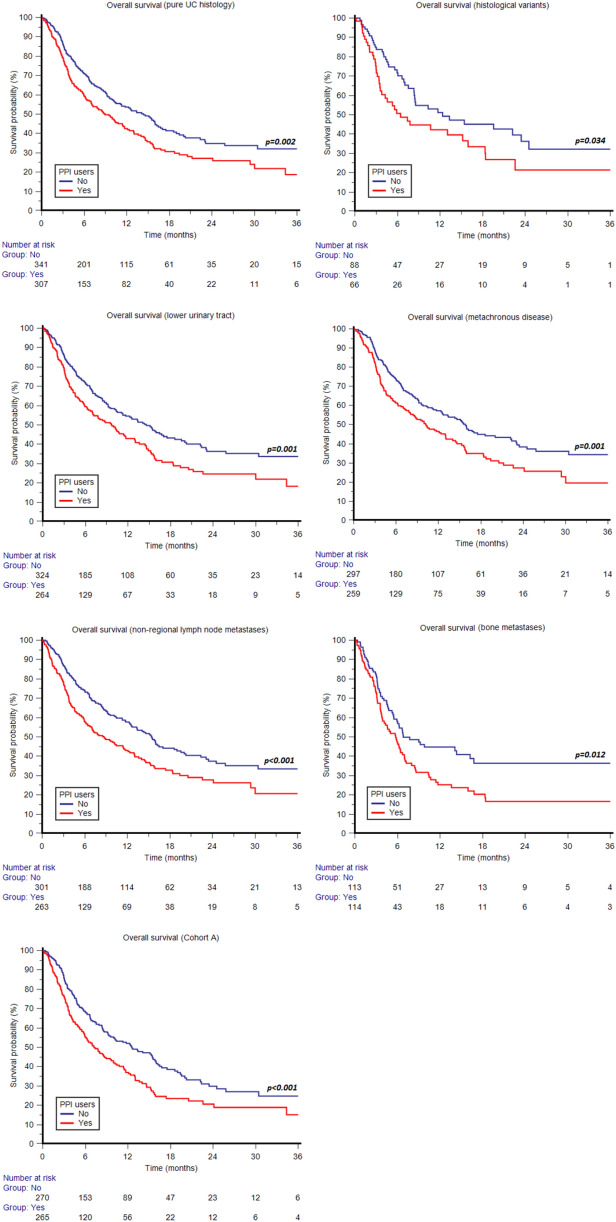

The association of concomitant use of PPIs with shorter OS was statistically significant in both males (p = 0.004) and females (p = 0.019) (Fig. 3); patients aged ≥ 65 years (p = 0.001) (Fig. 3); current or former smokers (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3); patients with ECOG-PS 0-1 (p = 0.004); patients with pure UC histology (p = 0.002) and those with other histological variants (p = 0.034) (Fig. 4); patients with UC of lower urinary tract (p = 0.001) (Fig. 4); patients with metachronous metastatic disease (p = 0.001) (Fig. 4); patients with non-regional lymph node metastases (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4); patients with bone metastases (p = 0.012) (Fig. 4); and patients in cohort A (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The difference in OS according to the use of PPIs was not statistically significant in patients aged < 65 years (p = 0.135); non-smokers (p = 0.057); patients with ECOG-PS ≥ 2 (p = 0.150); patients with upper urinary tract tumors (p = 0.112); patients with lung metastases (p = 0.179); patients with liver metastases (p = 0.122); patients with synchronous metastatic disease (p = 0.067); and patients in cohort B (p = 0.262). Similar to OS, the association of concomitant use of PPIs with shorter PFS was statistically significant in both males (p = 0.020) and females (p = 0.031) (Fig. 5); patients aged ≥ 65 years (p = 0.013) and those aged < 65 years (p = 0.05) (Fig. 5); current or former smokers (p = 0.006) (Fig. 5); patients with ECOG-PS 0-1 (p = 0.017); patients with pure UC histology (p = 0.006) (Fig. 5); patients with UC of lower urinary tract (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5); patients with metachronous (p = 0.025) and those with synchronous metastatic disease (p = 0.016); patients with non-regional lymph node metastases (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6); and patients in cohort A (p = 0.008) (Fig. 6). The difference in PFS according to the use of PPIs was not statistically significant in non-smokers (p = 0.12); patients with other histological UC variants (p = 0.120); patients with ECOG-PS ≥ 2 (p = 0.179); patients with upper urinary tract tumors (p = 0.595); patients with bone metastases (p = 0.317); lung metastases (p = 0.625); patients with liver metastases (p = 0.550) and those in cohort B (p = 0.150). The survival data are summarized in detail in Table 3. Forest plots summarizing HRs and 95% CIs for OS and PFS according to the PPI use in all patient subgroups are displayed in Fig. 7.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival according to concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) stratified by sex, smoking status and age

Fig. 4.

Overall survival according to concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) stratified by tumor histology, primary tumor site, metachronous disease, lymph node or bone metastases and pembrolizumab setting (second-line therapy after progression on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, Cohort A)

Fig. 5.

Progression-free survival according to concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) stratified by sex, age, smoking status, tumor histology and primary tumor site

Fig. 6.

Progression-free survival according to concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) stratified by synchronous metastatic disease, lymph node metastases and pembrolizumab setting (second-line therapy after progression on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, Cohort A)

Table 3.

Summary of patient survival data according to the specific subgroups

| Median OS (95% CI) | p value | Median PFS (95% CI) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI users | PPI non-users | PPI users | PPI non-users | |||

| Whole cohort | 8.7 months (6.9–11.4) | 14.1 months (10.4–16.2) | p < 0.001 | 4.5 months (3.7–6.3) | 7.2 months (5.7–9.1) | p = 0.002 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 10.0 months (7.2–13.0) | 15.1 months (11.1–17.0) | p = 0.004 | 5.0 months (3.8–6.4) | 6.9 months (5.6–9.1) | p = 0.020 |

| Females | 6.3 months (4.6–46.4) | 11.3 months (7.5–18.6) | p = 0.019 | 4.0 months (3.2–44.0) | 8.3 months (4.6–12.4) | p = 0.031 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 65 years | 9.7 months | 12.6 months | p = 0.135 | 4.2 months | 6.9 months | p = 0.05 |

| (5.-16.8) | 9.2–22.4) | (3.4–44.0) | (4.7–9.5) | |||

| ≥ 65 years | 8.7 months (6.4–11.4) | 14.1 months (10.0––17.0) | p = 0.001 | 4.6 months (3.6–6.4) | 7.5 months (5.6–10.0) | p = 0.013 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Current or former smokers | 10.0 months | 16.0 months (12.4–22.4) | p < 0.001 | 4.5 months (3.7––6.9) | 7.5 months (6.1–11.4) | p = 0.006 |

| (6.9–12.4) | ||||||

| Non-smokers | 7.4 months | 10.2 months | p = 0.057 | 4.5 months | 6.0 months | p = 0.12 |

| (4.6–12.2) | (7.5–14.1) | (3.4–6.6) | (4.2–9.5) | |||

| Histology | ||||||

| Pure UC | 8.9 months (7.0–11.5) | 14.3 months (10.4–16.5) | p = 0.002 | 5.3 months (3.7–6.6) | 7.2 months (5.7––9.4) | p = 0.006 |

| Other variants | 6.4 months (3.6–46.4) | 12.4 months (8.3–23.4) | p = 0.034 | 3.9 months (3.2–44.0) | 7.0 months (4.7–20.9) | p = 0.120 |

| ECOG-PS | ||||||

| 0–1 | 11.5 months | 16.2 months | p = 0.004 | 6.4 months | 8.5 months | p = 0.017 |

| (8.9–14.9) | (13.3–22.2) | (4.5–7.3) | (6.7–10.4) | |||

| ≥ 2 | 3.2 months (2.6–4.1) | 5.1 months (4.1––6.6) | p = 0.150 | 2.6 months (1.9–3.3) | 3.5 months (2.5–4.8) | p = 0.179 |

| Primary tumor site | ||||||

| Lower urinary tract | 9.7 months (7––11.7) | 14.6 months (11.1–17.5) | p = 0.001 | 4.5 months (3.7–6.3) | 7.7 months (6.2–9.9) | p < 0.001 |

| Upper urinary tract | 11.8 months (8.3–16.2) | 7.2 months (4.8–12.1) | p = 0.112 | 5.3 months (3.4–8.0) | 5.4 months (4.1–9.5) | p = 0.595 |

| Type of metastatic spread | ||||||

| Synchronous metastases | 6.2 months (4.0–9.7) | 10.0 months (7.4–47.2) | p = 0.067 | 3.6 months (2.6–5.8) | 6.6 months (3.9–9.5) | p = 0.016 |

| Metachronous metastases | 10.2 months | 15.8 months | p = 0.001 | 6.1 months | 7.7 months | p = 0.025 |

| (7.8–13.0) | (12.5–22.2) | (4.0–7.2) | (5.8–9.9) | |||

| Site of distant metastases | ||||||

| Lymph node (non-regional) | 8.7 months (6.4–11.7) | 15.4 months (12.5–19.0) | p < 0.001 | 4.5 months (3.5–6.3) | 8.6 months (6.4–12.4) | p < 0.001 |

| Bone | 5.8 months (3.9–7.0) | 6.8 months (5.5–16.2) | p = 0.012 | 3.3 months (2.9–4.6) | 3.8 months (3.2–5.6) | p = 0.317 |

| Lung | 8.1 months (5.8–11.7) | 11.3 months (7.4–15.5) | p = 0.179 | 6.2 months (3.5–7.2) | 5.5 months (4.1–7.7) | p = 0.625 |

| Liver | 4.5 months (3.6–8.1) | 10.0 months (6.7–16.0) | p = 0.122 | 3.6 months (2.5–4.5) | 3.9 months (3.3–4.9) | p = 0.550 |

| Pembrolizumab setting | ||||||

| Cohort A (progressed after first-line chemotherapy) | 7.2 months (5.9–9.7) | 12.6 months (9.2–15.8) | p < 0.001 | 4.3 months (3.5–6.1) | 6.4 months (4.8–8.4) | p = 0.008 |

| Cohort B (recurred within < 1 years from adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy) | 16.0 months (8.8–21.2) | 17.0 months (10.3–45.9) | p = 0.262 | 6.9 months (3.5–14.9) | 8.6 months (6.2–25.4) | p = 0.150 |

ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status; UC = Urothelial Carcinoma, CI = Confidence interval, y = years; statistically significant p values are in bold

Fig. 7.

Forest plots showing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to the PPI use in all patient subgroups

Objective response

Eighty patients (10%) achieved CR, 168 (21%) PR, 197 (24%) SD and 357 (44%) PD, with an ORR of 31%. The OS was significantly different according to the type of response: NR (95% CI NR–NR), 34.4 months (95% CI 22.4–47.2), 15.6 months (95% CI 12.4–19.4) and 4.3 months (95% CI 3.8–30.4) in patients with CR, PR, SD and PD, respectively (p < 0.001).

Stratified by concomitant medications, the ORR was 26% in PPI users and 36% in PPI non-users (CR = 8%, PR = 18%, SD = 24%, PD = 50% vs CR = 12%, PR = 24%, SD = 24%, PD = 40%; p = 0.127). No difference was found in terms of ORR between statin users versus non-users (ORR = 35%, CR = 12%, PR = 23%, SD = 22%, PD = 43% versus ORR = 29%, CR = 9%, PR = 20%, SD = 26%, PD = 45%; p = 0.364) or between metformin users versus non-users (ORR = 33%, CR = 11%, PR = 22%, SD = 24%, PD = 43%, vs. ORR = 31%, CR = 10%, PR = 21%, SD = 25%, PD = 44%; p = 0.762).

Discussion

In the last decade, immunotherapy has increasingly gained a key role in the treatment of several solid tumors and hematological malignancies. In addition, ICIs demonstrated a certain efficacy in various settings in solid tumors: neoadjuvant, adjuvant, first-line or successive lines of therapy. A perfect example of this expanding use of ICIs represents advanced UC. Since the initial second-line strategy approval for patients who progressed on a prior platinum-based chemotherapy, the use of ICIs in mUC has been quickly extended to the first-line setting in PD-L1-positive cisplatin-ineligible patients or any platinum-ineligible patients regardless of PD-L1 expression as well as to the switch maintenance therapy in platinum responders [28].

As we witness this indisputable therapeutic revolution, an emerging and important issue that remains to be solved is whether the concomitant administration of other drugs may impair or eventually enhance the efficacy of ICIs. This is a crucial question also considering that UC mostly affects elderly patients who may present other disorders and use several concomitant medications.

In our study, the concomitant use of PPIs was significantly associated with both shorter PFS and OS in mUC patients receiving pembrolizumab therapy. Furthermore, its independent adverse prognostic role was confirmed in the multivariate analysis. The use of statins or metformin did not affect the response or survival outcomes of these patients.

PPIs, statins and metformin represent the most commonly prescribed medications in the global population; however, their potential to affect the efficacy of ICIs in cancer patients has not been fully elucidated.

The ability of PPIs to influence the efficacy of ICIs may be mainly related to the modifications induced by PPIs in gut microbiome, which plays a crucial role in patients treated with ICIs for solid tumors [29]. It has been shown that PPI use can induce marked alterations to the intestinal microbiome including changes in composition, reduction of the alpha diversity, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and manifestation of oral bacteria in more distal parts of the intestine [30–32]. In this regard, Imhann et al. [33] observed that PPI use is associated with the presence of multiple oral bacteria over-represented in the fecal microbiome, with an overall significant increase in bacteria, including Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Escherichia coli. There has been an accumulating body of evidence that the concomitant use of PPIs could have detrimental effect on ICI therapy in various cancer types [16–18]. In particular, this issue has been underexplored in the field of mUC. Several retrospective studies have been reported recently. However, their crucial limitation is based on a relatively small number of included patients, especially those of PPI users, potentially introducing a significant bias. Thus, there has been a lack for solid data from large studies. The association of shorter PFS and OS with concomitant use of PPIs (HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.23–2.35, p = 0.001 and HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.28–3.18, p = 0.003, respectively) in a cohort of 227 mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab has been found in a retrospective study conducted by Fukuokaya et al. [13]. Similar data were reported in two other studies conducted by Tomisaki et al. and Okuyama et al. including 40 and 155 patients, respectively. These results are in agreement with our large study including 802 patients (372 PPI users). Aside from mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab, similar findings were found in a post hoc analysis of IMvigor210 and IMvigor211 clinical trials conducted by Hopkins et al. [9]. They found that PPI use was associated with shorter PFS and OS (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.18–1.62, p < 0.001 and HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.27–1.83, p < 0.001, respectively) in advanced-stage UC patients treated with atezolizumab, while there was no association in those treated with chemotherapy [10].

On the other hand, a study by Kunimitsu et al. including 79 patients failed to show such a prognostic role of the use of PPIs in advanced-stage UC when treated with pembrolizumab [15]. Nonetheless, it is another study fundamentally limited by a small cohort size.

Notably, our data show that the use of PPIs was significantly associated with poor outcome only in patients with primary tumors of the lower urinary tract but not in those with primary tumors of the upper urinary tract. This may be explained by a relatively small number and the overall poor prognosis of mUC patients with tumors originating in the upper urinary tract and their generally reduced benefit from ICIs [34] and a distinct genomic background of this specific subgroup [35]. Similar results have been recently reported by Taguchi et al., who successfully validated the prognostic capability of the drug score counted from the baseline use of antibiotics, PPIs and corticosteroids in advanced-stage mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab. In agreement with our study, they found that drug score was significantly correlated with survival outcomes in patients with primary tumors of the lower urinary tract but not in those with primary tumors of the upper urinary tract [36]. However, further elucidation of this issue is needed. We found no significant correlation between the PPI use and ORR, indirectly indicating that PPIs mainly impact duration of response (DR), rather than objective response to therapy. However, DR was not assessed specifically in the present study.

Anticancer properties of statins such as the inhibition of tumor cell growth, invasion and metastatic potential have been suggested in various experimental studies [37–39]. Notwithstanding, clinical studies evaluating the impact of statin use in cancer patients including those with UC have been conducted with inconclusive results. Moreover, there are no data on the role of the statin use in mUC patients treated with ICIs. Ferro et al. suggested that statins may have a beneficial effect on recurrence rates in patients with high-grade non-muscle invasive urothelial bladder cancer in a multicenter study including 1510 patients [40]. Oppositely, another recent retrospective study by Haimerl et al. found no impact of statin use on bladder cancer recurrence or survival in a cohort of 972 patients [41]. In our study, we found no impact of the concomitant statin use in mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab.

Metformin represents another commonly used drug with suggested anticancer activity, which is related to both direct effects on cancer cells based on inhibition of cancer-related signaling pathways and indirect effects on the host based on lowering blood glucose and insulin as well as anti-inflammatory effects [42, 43]. Although several retrospective studies show the association of metformin use with favorable prognosis of patients with cancer, there are no data on its role in patients with mUC treated with ICIs. Our data show no impact of the concomitant metformin use in mUC patients treated with pembrolizumab.

Our study presents several limitations, mainly due to its retrospective nature. A centralized review of radiological imaging was not performed. The dosage and duration of the investigated comedication exposure could not be assessed from the available data sources. Thus, we were not able to investigate a difference between chronic and temporary use after pembrolizumab treatment initiation. Furthermore, we had no available data on other concomitant medications (i.e. steroids, antibiotics) or patients’ comorbidities that could affect the efficacy of pembrolizumab. Consequently, our results should be interpreted with caution and are in need of a further prospective validation. On the other hand, the major strength of our study is based on a large patient population, which allowed us to perform a detailed subgroup analysis.

In conclusion, our data show that the concomitant use of PPIs may adversely affect the outcome of mUC patients treated with second-line pembrolizumab. Further studies investigating the biological and immunological background of this interaction are warranted in order to optimize the outcome of patients receiving immunotherapy in this setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients voluntarily taking part in the study.

Author contributions

Manuscript: Use of concomitant proton pump inhibitors, statins, or metformin in patients treated with pembrolizumab for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Data from the ARON-2 retrospective study. Fiala et al. O. Fiala: Investigation, Writing - Original Draft M. Santoni: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft S. Buti: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft All authors: Investigation

Funding

None to declare.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

O. Fiala received honoraria from Roche, Janssen, GSK and Pfizer for consultations and lectures unrelated to this project. S. Buti received honoraria as speaker at scientific events and advisory role by BMS, Pfizer, MSD, Ipsen, AstraZeneca, Merck, all unrelated to this project. M. Santoni has received research support and honoraria from Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, MSD, Astellas and Bayer, all unrelated to this project. R. Kanesvaran has received fees for speaker bureau and advisory board activities from the following companies; Pfizer, MSD, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Amgen, Astellas and Bayer, all unrelated to this project. E. Grande has received honoraria for speaker engagements, advisory roles or funding of continuous medical education from Adacap, AMGEN, Angelini, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Blueprint, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caris Life Sciences, Celgene, Clovis-Oncology, Eisai, Eusa Pharma, Genetracer, Guardant Health, HRA-Pharma, IPSEN, ITM-Radiopharma, Janssen, Lexicon, Lilly, Merck KGaA, MSD, Nanostring Technologies, Natera, Novartis, ONCODNA (Biosequence), Palex, Pharmamar, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Genzyme, Servier, Taiho, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and has received research grants from Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Astellas, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, all unrelated to this project. F. S. M. Monteiro has received research support from Janssen, Merck Sharp Dome and honoraria from Janssen, Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck Sharp Dome, all unrelated to this project. C. Porta has received honoraria from Angelini Pharma, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Eisai, General Electric, Ipsen and MSD and acted as a Protocol Steering Committee Member for BMS, Eisai and MSD, all unrelated to this project. Z. Myint has received research support from Merck unrelated to this project. J. Molina-Cerrillo declares consultant, advisory or speaker roles for IPSEN, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen, and BMS and has received research grants from Pfizer, IPSEN and Roche, all unrelated to this project. P. Giannatempo has received research support from Ipsen, Astra Zeneca, MSD and honoraria for speaker engagements, advisory roles from Astellas, MSD, Janssen, Pfizer, all unrelated to this project. E. T. Lam has received institutional research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. The other authors declare to have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ondřej Fiala and Sebastiano Buti have contributed equally to this work.

Joaquim Bellmunt and Matteo Santoni are co-Senior Authors.

References

- 1.Taguchi S, Kawai T, Nakagawa T, Miyakawa J, Kishitani K, Sugimoto K, et al. Improved survival in real-world patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma: a multicenter propensity score-matched cohort study comparing a period before the introduction of pembrolizumab (2003–2011) and a more recent period (2016–2020) Int J Urol. 2022;29(12):1462–1469. doi: 10.1111/iju.15014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, Fradet Y, Lee JL, Fong L, et al. KEYNOTE-045 investigators. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1015–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters S, Dziadziuszko R, Morabito A, Felip E, Gadgeel SM, Cheema P, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;28(9):1831–1839. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01933-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A, Baron A, Necchi A, Bedkeet J, et al. Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):312–322. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel MR, Ellerton J, Infante JR, Agrawal M, Gordon M, Aljumailyet R, et al. Avelumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum failure (JAVELIN Solid Tumor): pooled results from two expansion cohorts of an open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):51–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buti S, Bersanelli M, Perrone F, Tiseo M, Tucci M, Adamo V, et al. Effect of concomitant medications with immune-modulatory properties on the outcomes of patients with advanced cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: development and validation of a novel prognostic index. Eur J Cancer. 2021;142:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buti S, Bersanelli M, Perrone F, Bracarda S, Di Maio M, Giusti R, et al. Predictive ability of a drug-based score in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving first-line immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takada K, Buti S, Bersanelli M, Shimokawa M, Takamori S, Matsubara T, et al. Antibiotic-dependent effect of probiotics in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins AM, Kichenadasse G, Karapetis CS, Rowland A, Sorich MJ. Concomitant antibiotic use and survival in urothelial carcinoma treated with atezolizumab. Eur Urol. 2020;78(4):540–543. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins AM, Kichenadasse G, Karapetis CS, Rowland A, Sorich MJ. Concomitant proton pump inhibitor use and survival in urothelial carcinoma treated with atezolizumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5487–5493. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruiz-BañobreJ M-DA, Fernández-Calvo O, Fernández-Núñez N, Medina-Colmenero A, Santomé L, et al. Rethinking prognostic factors in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma in the immune checkpoint blockade era: a multicenter retrospective study. ESMO Open. 2021;6(2):100090. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishiyama Y, Kondo T, Nemoto Y, Kobari Y, Ishihara H, Tachibana H, et al. Antibiotic use and survival of patients receiving pembrolizumab for chemotherapy-resistant metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(12):834.e21–834.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuokaya W, Kimura T, Komura K, Uchimoto T, Nishimura K, Yanagisawa T, et al. Effectiveness of pembrolizumab in patients with urothelial carcinoma receiving proton pump inhibitors. Urol Oncol. 2022;40(7):346.e1–346.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomisaki I, Harada M, Minato A, Nagata Y, Kimuro R, Higashijima K, et al. Impact of the use of proton pump inhibitors on pembrolizumab effectiveness for advanced urothelial carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(3):1629–1634. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunimitsu Y, Morio K, Hirata S, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto K, Omura T, Hara T, et al. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on survival outcomes in patients with metastatic or unresectable urothelial carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. Biol Pharm Bull. 2022;45(5):590–595. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b21-00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuyama Y, Hatakeyama S, Numakura K, Narita T, Tanaka T, Miura Y, et al. Prognostic impact of proton pump inhibitors for immunotherapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma. BJUI Compass. 2021;3:154–161. doi: 10.1002/bco2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizzo A, Santoni M, Mollica V, Ricci AD, Calabrò C, Cusmai A, et al. The impact of concomitant proton pump inhibitors on immunotherapy efficacy among patients with urothelial carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2022;12(5):842. doi: 10.3390/jpm12050842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triadafilopoulos G, Roorda AK, Akiyama J. Indications and safety of proton pump inhibitor drug use in patients with cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2013;12(5):659–672. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.797961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalabi M, Cardona A, Nagarkar DR, Scala AD, Gandara DR, Rittmeyer A, et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy and atezolizumab in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer receiving antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors: pooled post hoc analyses of the OAK and POPLAR trials. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(4):525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan ME, Freedberg DE, Abrams JA, Poole AC, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65(5):749–756. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng R, Zhang H, Li Y, Shi Y. Effect of antacid use on immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced solid cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Immunother. 2022;46(2):43–55. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciccarese C, Iacovelli R, Buti S, Primi F, Astore S, Massari F, et al. Concurrent nivolumab and metformin in diabetic cancer patients: is it safe and more active? Anticancer Res. 2022;42(3):1487–1493. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santoni M, Molina-Cerrillo J, Myint ZW, Massari F, Buchler T, Buti S, et al. Concomitant use of statins, metformin, or proton pump inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line combination therapies. Target Oncol. 2022;17(5):571–581. doi: 10.1007/s11523-022-00907-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santoni M, Massari F, Matrana MR, Basso U, De Giorgi U, Aurilio G, et al. Statin use improves the efficacy of nivolumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrone F, Minari R, Bersanelli M, Bordi P, Tiseo M, Favari E, et al. The prognostic role of high blood cholesterol in advanced cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother. 2020;43(6):196–203. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantini L, Pecci F, Hurkmans DP, Belderbos RA, Lanese A, Copparoni C, et al. High-intensity statins are associated with improved clinical activity of PD-1 inhibitors in malignant pleural mesothelioma and advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mollica V, Rizzo A, Montironi R, Cheng L, Giunchi F, Schiavina R, et al. Current strategies and novel therapeutic approaches for metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6):1449. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seto CT, Jeraldo P, Orenstein R, Chia N, DiBaise JK. Prolonged use of a proton pump inhibitor reduces microbial diversity: implications for Clostridium difficile susceptibility. Microbiome. 2014;2:42. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clooney AG, Bernstein CN, Leslie WD, Vagianos K, Sargent M, Laserna-Mendieta EJ, et al. A comparison of the gut microbiome between long-term users and non-users of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(9):974–984. doi: 10.1111/apt.13568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuda A, Suda W, Morita H, Takanashi K, Takagi A, Koga Y, et al. Influence of proton-pump inhibitors on the luminal microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6(6):e89. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imhann F, Bonder MJ, Vich Vila A, Fu J, Mujagic Z, Vork L, et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut. 2016;65(5):740–748. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thouvenin J, Martínez Chanzá N, Alhalabi O, Lang H, Tannir NM, Barthélémy P, et al. Efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in upper tract urothelial carcinomas: current knowledge and future directions. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(17):4341. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su X, Lu X, Bazal SK, Compérat E, Mouawad R, Yao H, et al. Comprehensive integrative profiling of upper tract urothelial carcinomas. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02230-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taguchi S, Kawai T, Buti S, Bersanelli M, Uemura Y, Kishitani K, et al (2023) Validation of a drug-based score in advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab. 10.2217/imt-2023-0028. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Chan KK, Oza AM, Siu LL. The statins as anticancer agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keyomarsi K, Sandoval L, Band V. Synchronization of tumor and normal cells from G1 to multiple cell cycles by lovastatin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong WW, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, Penn LZ. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: the statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia. 2002;16:508–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferro M, Marchioni M, Lucarelli G, Vartolomei MD, Soria F, Terracciano D, et al. Association of statin use and oncological outcomes in patients with first diagnosis of T1 high grade non-muscle invasive urothelial bladder cancer: results from a multicenter study. Minerva Urol Nephrol. 2021;73(6):796–802. doi: 10.23736/S2724-6051.20.04076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haimerl L, Strobach D, Mannell H, Stief CG, Buchner A, Karl A, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the impact of non-oncologic chronic drug therapy on the survival in patients with bladder cancer. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(2):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s11096-021-01343-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samuel SM, Varghese E, Kubatka P, Triggle CR, Büsselberg D, et al. Metformin: the answer to cancer in a flower? Current knowledge and future prospects of metformin as an anti-cancer agent in breast cancer. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):846. doi: 10.3390/biom9120846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YC, Li H, Wang J. Mechanisms of metformin inhibiting cancer invasion and migration. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(9):4885–4901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]